Heavy vehicle transport: state of the industry

3.1

In the previous chapter, the committee examined the roles of driver,

employer, trainer, assessor and state and federal government agencies in the

context of a heavy vehicle incident on the M5 Freeway. This exercise sharpened

the committee's focus on structural problems that threaten the safety and

economic viability of the road transport industry.

3.2

In this chapter, the committee discusses the key issues which indicate that

all sectors of the industry may not be thriving including: a high road toll

from truck crashes, a shortage of skilled drivers and adverse safety outcomes

arising from continued economic pressure.

3.3

Evidence to the inquiry highlighted the need to find economic solutions

for the industry. In particular, attention was drawn to the need to accelerate

the progress of reform by way of updating the chain of responsibility laws,

mandating the use of electronic work diaries and instituting 30 day minimum

payment terms. This chapter considers these reforms.

An industry in crisis

Road toll increases

3.4

The committee heard startling evidence which indicated that the road

toll from truck crashes is at a record high level and is continuing to

increase.[1]

According to the TWU, in the 10 years to 2014, over 2500 people died in truck

crashes on Australia's roads. The committee shares the view of submitters that

'this is not a statistic that should prompt any government to stand idly by'.[2]

3.5

The committee was not surprised to hear that heavy vehicles are 'over‑represented

in road crash fatalities and injuries' and that 'hospital admissions and

injuries are trending upwards'.[3]

Toll Group told the committee that approximately '350 truck rollovers are

reported each year in Australia'.[4]

As the TWU remarked, 'no other industry injures 5350 people per year at the

rate of 31 per day'.[5]

3.6

The difficulty of attracting and retaining skilled heavy vehicle drivers

was repeatedly raised in evidence to this inquiry. This evidence is

unsurprising when weighed against the statistics on fatalities. In 2016 'over

one in three workplace deaths involved transport workers, with 64 deaths out of

the total of 178'.[6]

Indeed, Safe Work data indicates that of the 100 people who died at work between

1 January 2017 and 20 July 2017, 42 were employed in the transport, postal and

warehousing industry.[7]

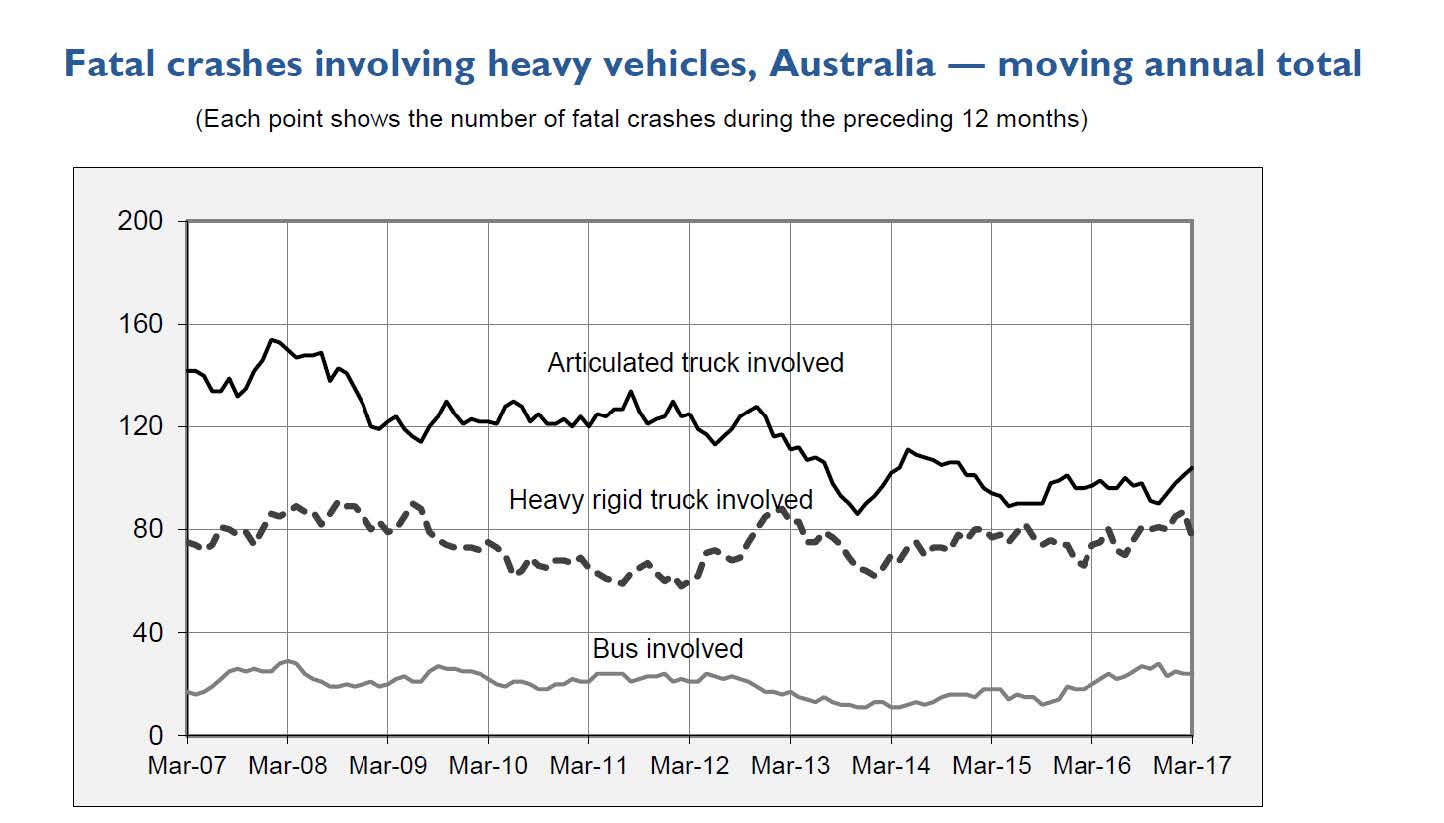

3.7

Furthermore, recent data from the Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport

and Regional Economics (BITRE) demonstrates a steady increase in fatal crashes

involving heavy vehicles:

Fatal crashes involving articulated trucks in the last year

have increased by 7.2 per cent compared with the previous year, an increase by

an average of 0.9 per cent per year over the three years to March 2017. Fatal

crashes involving heavy rigid trucks have increased by 4.1 per cent compared

with the previous year, an increase by an average of 2.5 per cent per year over

the three years to March 2017.[8]

3.8

During the 12 months to the end of March 2017, 205 people died in

181 crashes involving articulated or heavy rigid trucks. This is a higher

fatality rate than that over the previous 12 months when 185 people died in 170

crashes, as shown on the graph that follows.[9]

3.9

While considering the issue of heavy vehicle driver training at length

in Chapter 4, the committee is mindful that other road users have a role to

play in reducing the heavy vehicle road toll. Heavy vehicle trainer and

assessor, Mr Tony Richens, provided evidence that 'in accidents involving heavy

vehicles, 80 per cent of the fault lies with the other vehicle in the

accident'.[10]

He gave examples of unsafe practices by light vehicle drivers in their

interaction with heavy vehicles:

You need only to travel in a heavy vehicle on a public road

to see that the majority of car drivers have no understanding of the room

required by heavy vehicles to stop, turn or travel through roundabouts and they

certainly have no awareness of the vision limitations from the cab of the

vehicle[11]

3.10

To improve the awareness of other road users, Road Freight NSW

recommended 'a working committee to scope out better ways to educate

light-vehicle users and cyclists in their interactions with heavy‑vehicle

users for the purposes of attaining safer roads'.[12]

More specifically, Mr Richens suggested that driving instructors could undergo

heavy vehicle training as part of their accreditation, with a view to fostering

greater awareness in their students, of heavy vehicles on the roads. He also

made the point that caravan drivers could also benefit from education and

training about heavy vehicle driving.[13]

Shortage of drivers

3.11

The committee heard that, alongside the increased freight task, it is

relatively difficult for transport companies to find qualified drivers. Mr

Simon O'Hara reported back from Road Freight NSW's most recent conference that:

...the prevailing view...is that it is difficult to get truck

drivers. It is even harder to find those who are properly qualified and have

experience. There is a problem in the industry and it relates to being able to

capture younger people coming in. A lot of the older truck drivers have a lot

of experience and they are exiting the industry.[14]

3.12

Evidence to the committee suggests that the industry will remain

unattractive to younger people, prolonging the shortage of drivers, until such

time as its economic viability is assured. Mr Sheldon of the TWU warned that:

Unless we can deal with the economics in an industry that is

being driven into the ground—low margins, lack of capacity to train and now,

more than ever, a shortage of drivers that is looming. Over the next decade

over 40 per cent of drivers will be retiring, and there are not drivers being

trained up.[15]

3.13

The committee is aware that not all transport industry players are

resorting to hiring practices that jeopardise the safety of the industry. On

the contrary, the industry is largely comprised of honest and experienced

operators who know that safe practices are better for business. As the

Queensland department told the committee:

Our understanding is that Australian trucking companies

actually have a preference for people holding an Australian licence, and that

is due to the cost of the machinery that they are handing over. They seek to

have the highest skilled people possible.[16]

3.14

Unless addressed, however, the industry's ageing workforce has

consequences that extend beyond the economics of the industry as it loses the

'safer culture around the older truck drivers'.[17]

Mr Sheldon observed that the 'squeeze in transport' has had 'heartbreaking

results' as unskilled and unsafe drivers find themselves in situations similar to

that of the M5 incident:

This squeeze sees companies hiring drivers through the

loopholes you have discovered, who are so unskilled they cannot unhitch trucks

or reverse them, holding up traffic for hours on one of our busiest

thoroughfares. It sees labour agreements to bring in overseas workers so they

can be paid less.[18]

Committee view

3.15

The committee is strongly of the view that the high road toll amongst

transport workers is unacceptable and that the increasing number of road

fatalities involving heavy vehicles must be addressed.

3.16

The committee encourages all levels of government to continue to

dedicate resources to driver education, and to highlight the specific

conditions created by heavy vehicles our roads. Further, the committee notes

that vehicle design has a role to play, as 'modern cars are designed with

indicators that can be very hard to see from the elevated position of a truck'.[19]

3.17

In the committee's view, a connection can be made between the rising

heavy vehicle road toll and an increasing number of non-traditional delivery

services including Amazon and UberFreight. The committee heard that these

services may not share the wider industry's commitment to

safety. Specifically, the committee is alarmed by 'initiatives' such as

Amazon's two-day delivery guarantee which prioritises speed of delivery over

safety, while also raising consumer expectations about how fast their goods can

arrive.[20]

3.18

In an industry where low profit margins place considerable financial

pressures on truck drivers while at the same time, demands on them continue to

grow, the 'two-day turnaround' has a significant impact on industry safety and

profitability. As Mr Sheldon from the TWU noted:

If you are driving an unprofitable business with the intent

of driving down prices, driving down costs in an industry that has low margins

then it is extremely dangerous, and a two-day turnaround in this country is extremely

dangerous.[21]

3.19

If Australia is to arrest the rising road toll involving heavy vehicles,

it must continue to build skills and expertise in the transport industry while

fostering a greater awareness of heavy vehicle driving conditions among light

vehicle drivers. It is imperative that younger heavy vehicle drivers have the

opportunity to learn safe practices from their experienced peers. To facilitate

this, governments must work together to make heavy vehicle driving a safe and

attractive career path.

3.20

The committee strongly encourages governments to consider adopting measures

which encourage younger drivers to seek employment in the heavy vehicle

industry. To this end, the committee encourages the Australian Government to

work with its state and territory counterparts and industry to establish an

attractive traineeship or apprenticeship scheme.

Addressing supply chain issues

3.21

In addition to incentives for younger drivers to enter the transport

industry, witnesses told the committee that there is a critical need to look at

structural and economic reform to address supply chain issues. Mr Salvatore

Petroccitto of the National Heavy Vehicle Regulator articulated that:

...when economic times are tougher, one of the areas that

sometimes is compromised in the industry is maintenance—and there is the impact

that then has on the heavy vehicle itself. As the economic pressures become

greater and the ability for an operator to make ends meet diminishes, some

things have to give.[22]

3.22

Likewise, the TWU warned that when economics is allowed to drive safety

practices 'you are then driving people to their death'. Mr Sheldon explained:

If you drive down to the lowest cost—that is the lowest cost

you will get—in the trucking industry that means both sweating the capital

invested in the truck and sweating the driver. When you sweat the drivers and

sweat the capital invested in the truck, you see the sorts of incidents that

occurred at the M5 and the airport tunnel. You see the incident only 12 months

beforehand where two people were incinerated after a refuelling truck blew into

flames and subsequently the company was found to have been sweating the

capital.[23]

3.23

These examples highlight the need to have an effective regulatory model

and stronger accountability measures throughout the supply chain. Mr Sheldon considered

what was required to prevent a reoccurrence of the M5 incident:

There needs to be an accountability system for looking at

low-cost contracts in a transport industry which is highly squeezed on margins,

which then turns to drivers' wages and conditions being reduced or, I would

suggest, bogus employment and engagement of immigrant workers on visa

arrangements...The government previously abolished a system of safe roads which

ensured wealthy retailers and manufacturers were held to account over

exploitation in supply chains. This had the capacity to be extended to the

exploitation of visa holders.[24]

3.24

The link between supply chain issues and safety has been well understood

for the best part of a decade. As far back as July 2008, federal, state and

territory transport ministers meeting as the Australian Transport Council (now

the Transport and Infrastructure Council) requested that the National Transport

Commission (NTC), an independent statutory body, investigate and report on

driver remuneration and payment methods in the transport industry. This work

included an examination of:

-

the impact of driver remuneration and payment methods on safety

risks and outcomes within the heavy vehicle transport industry; and

-

how chain of responsibility obligations can be applied.[25]

3.25

Reporting in October 2008, the NTC found that 'further reforms are

needed to address the underlying economic factors which create an incentive

for, or encourage, unsafe on-road practices'.[26]

It recommended that ministers endorse 'a system of safe payments for employees

and owner-drivers...reinforced by appropriate chain of responsibility provisions

in model road transport law'.[27]

3.26

After further consideration by the government's Safe Rates Advisory

Group,[28]

the framework for a safe payments system was given legal effect in 2012 under

the Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal (the tribunal).[29]

Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal

3.27

The committee remains troubled by the government's decision to abolish the

Road Safety Remuneration Tribunal by legislation on 19 April 2016, at

a time when the transport industry most needed regulatory support.

3.28

Mr Sheldon of the TWU expressed little optimism when considering the

state of the industry and the lost opportunity to improve safety arrangements:

It is an industry in crisis, yet the only intervention that

has been made so far is to tear down the one body that had the ability to

investigate and enforce safety arrangements. That was the Road

Safety Remuneration Tribunal.[30]

3.29

The committee expressed the strong view in its interim report that the

repeal of the tribunal was a retrograde step for road safety in Australia. This

view was informed by evidence of sustained low margins and poor safety

practices in the industry caused by the power imbalance between clients and

operators.[31]

Throughout the inquiry, the committee heard evidence in support of the tribunal,

including from drivers, their families and road transport companies.[32]

3.30

The TWU argued that the opportunity to address the economic and safety

issues (that are entwined in the heavy vehicle industry) was lost with the

tribunal's abolition, and noted that the tribunal:

...could have dealt directly with the training initiatives, the

training requirements and obligations on clients as well as transport

operators, and gone to the core question of the economic imperatives that drive

unsafe practices, with the intent of bringing in a level playing field for

everybody in the market so that skill, ability and entrepreneurship were what

won contracts, rather than exploitation.[33]

3.31

The tribunal had made two enforceable orders that applied to road transport drivers in

supermarket distribution or long distance operations. The first, the Road Transport

and Distribution and Long-Distance Operations Road Safety Remuneration Order

2014, imposed health and safety and contract obligations, including safe

driving plans and contracts. It also required owner drivers to be paid by

transport operators within 30 days of work carried out. The order applied from

1 May 2014 until 12 am on 21 April 2016.[34]

3.32

The second order, the Contractor Driver Minimum Payments Road Safety

Remuneration Order 2016, had effect from 4.15 pm on 7 April 2016 to 12 am

on 21 April 2016. It provided minimum pay rates and unpaid leave for

contractor drivers.[35]

3.33

Since the abolition of the tribunal and its orders, the committee has

seen little progress towards a resolution of the significant issues that were advanced

under its stewardship. The committee heard that owner or contractor drivers

still face considerable economic pressure, which can lead them to accept inferior

contract terms and less than safe working conditions. Mr Sheldon gave evidence

that:

There are owner-drivers who certainly take a great deal of

pride in saying no, but, when you are economically pressured and stressed,

whether you are a transport operator of a fleet or an owner-driver, you put

your hand up to take the load rather than lose your house and lose your

business. That sort of economic pressure is what needs to be dealt with. In a

lot of those reports, owner-drivers are usually on the worst receiving end of

pressure and exploitation.[36]

3.34

In the committee's view, urgent and cooperative action is required

across government to address, in particular, the issues of payment terms, chain

of responsibility legislation and the use of electronic work diaries.

Committee view

3.35

In order to advance safety in the industry, the committee recommends

that the Australian Government organise a series of industry-led roundtables

for the purposes of formulating recommendations for government on the

establishment of an independent industry body. This industry body should be

empowered to enforce supply chain standards while also setting and enforcing

sustainable, safe rates for the transport industry.

Recommendation 7

3.36

The committee recommends that the Australian Government convene a

series of industry-led roundtables to make recommendations to government to

establish an independent industry body which has the power to formulate,

implement and enforce supply chain standards and accountability as well as

sustainable, safe rates for the transport industry.

Payment terms

3.37

The abolition of the tribunal is, in the committee's view, a lost

opportunity to address the pervasive issue of payment terms for heavy vehicle

drivers. The tribunal's second order, Contractor Driver Minimum Payments

Road Safety Remuneration Order 2016 regulated conditions for contractor

drivers and provided a minimum remuneration schedule. Amongst other

requirements, the order set new conditions for payment. It required contractor

drivers to be paid within 30 days of the work being undertaken.[37]

3.38

The matter of payment terms was one of the key issues for the industry.

The ATA had informed the committee in 2015 that the terms of payment had been

'[g]rossly deficient'.[38]

3.39

Mr Cameron Dunn of Australian transport company FBT Transwest gave

evidence that when dealing with larger companies, businesses such as his were

'being pushed out to 120 days in terms of payments', which had a substantial

impact on cash flow.[39]

He explained that during the period that he was not receiving such payments,

which was a considerable length of time, his company still had to meet its

financial obligations to staff and service providers. By way of comparison, Mr

Dunn noted that his company paid drivers within seven days, tow operators

within 14 days and the fuel bills within 30 days.[40]

Heavy Vehicle National Law and

chain of responsibility

3.40

As discussed in the committee's interim report, most Australian

jurisdictions adopted the Heavy Vehicle National Law (HVNL) as a uniform model

for aspects of heavy vehicle regulation in 2014, with the result that fatigue

management and certain vehicle standards now benefit from a national approach.[41]

3.41

In 2015, the committee heard that work to adopt the HVNL in Western Australia

and the Northern Territory was ongoing.[42]

The committee reaffirms its recommendation that the West Australian and

Northern Territory governments work towards adoption.

3.42

The HVNL is administered by the independent National Heavy Vehicle

Regulator (NHVR) which has policy responsibility for a range of work, and

health and safety issues in the heavy vehicle industry, including the

obligations referred to as the 'chain of responsibility'.[43]

Toll Group's submission explained the chain of responsibility as applied in the

HVNL:

The heavy vehicle national law incorporates the concept of 'chain

of responsibility' (CoR) which imposes duties and obligations on all parties in

the supply chain to ensure safe on-road outcomes. In deciding whether operators

have taken reasonable steps to manage speed, fatigue, and mass, dimension and

load restraint, regulators and enforcers are required to consider the 'measures

available' and the 'measures taken' to manage those risks.[44]

3.43

After undertaking an industry consultation process in 2016, the NHVR

announced that changes to the Chain of Responsibility (CoR) laws will be

introduced in mid-2018 which 'aim to complement heavy vehicle and national

workplace safety laws, and place a positive duty of care on all heavy vehicle

supply chain parties'. The NVHR announced a series of national information

sessions for businesses to introduce two new tools, the 'Chain of

Responsibility Gap Assessment Tool' and 'Introduction to Risk Management – A

Heavy Vehicle Industry Guide'.[45]

3.44

The committee recognises the potential for HVNL reforms to increase

awareness and application of the chain of responsibility. Many witnesses were

also in favour of such reforms. The ATA put forward a view that this will

reduce what it sees as 'red tape' in the current HVNL:

The chain of responsibility laws in the heavy vehicle

national law states are being reformed...They will involve a dramatic reduction

in absolutely ridiculous prescriptive red tape in those laws.[46]

3.45

Mr Simon O'Hara of Road Freight NSW described chain of responsibility

legislation as 'part of the push for safety and greater compliance', and

outlined the organisation's role in running successful roadshows in NSW on the

legislation alongside the NHVR.[47]

At the same time, he acknowledged that it was hard to reach those operators who

do not comply, stating:

The point I would make to you is that those operators that

attend the chain of responsibility seminars are the ones that do want to

comply. There is a whole other part of the industry that possibly has a

different view.[48]

3.46

Mr O'Hara underlined the 'need for chain of responsibility to be

properly applied', pointing to a 'deficit in legislation' that saw an

Australian company fined for the non‑compliant actions of an overseas

counterpart.[49]

Electronic work diaries

3.47

It was brought to the committee's attention that recent NHVL reforms do

not address the use of electronic work diaries (EWDs) to monitor

and record the work and rest times of heavy vehicle drivers.[50]

The committee's interim report noted strong support for the use of electronic

work diaries as a method of reducing fatigue.[51]

The NHVR submitted in 2015 that:

Electronic work diaries are fundamental to risk management

and safety data for the regulator. They are an early step towards the future

policy framework being pursued by the regulator, where operators and drivers

will be able to access increased productivity benefits in exchange for access

to continuous-monitoring technology that allows full risk-based assessment of

individual trucks, drivers and operators.[52]

3.48

The committee's interim report encouraged the widespread use of

electronic work diaries throughout the industry on a voluntary basis, noting

advice that the necessary legislative arrangements were already in place:

In November 2014 the Transport and Infrastructure Council

endorsed the necessary legislative amendments to the Heavy Vehicle National Law

for the implementation of Electronic Work Diaries. The NHVR is currently

working to progress arrangements for the implementation of this technology.[53]

3.49

More recently, the NHVR website announced the regulator's intention to 'commence

the assessment and approval process for EWDs as a voluntary alternative to

written work diaries in late 2017'.[54]

3.50

Given that the use of electronic work diaries appears to have broad

industry support and legislative backing, the committee strongly encourages the

NHVR to complete the overdue assessment and approval process as a matter of

urgency.

Committee view

3.51

The committee has heard the call for 'proactive regulation introduced by

people with knowledge and understanding of the industry',[55]

and sees the need for an open dialogue between the transport industry and

regulators to maintain the priority and momentum of significant reforms.

3.52

The TWU agreed on the need to bring the respective parties together.[56]

Mr Sheldon made the point, however, that despite the best intentions of

industry, there would be new industry players who would have a disruptive

effect:

For all the good people that will sit around the table, with

a ruthless disregard for the law, it is obvious that Amazon and Uber Freight

coming into this market will drive the market to its furthest logical

consequences, which will be more injuries and deaths and exploitation.[57]

3.53

The committee views the emergence of new players as an even stronger

incentive to build consensus through a cooperative and industry-led forum.

Recognising that regulators and industry already agree on safety as the first

priority, the committee considers that their collective expertise and goodwill

could be channelled into the resolution of now well-documented supply chain

issues.

3.54

With two jurisdictions working towards implementation of the HVNL, and

broad agreement on a range of reform measures, the committee sees great

potential for industry to drive the policy agenda and improve safety outcomes

in a permanent fashion.

3.55

To this end, the committee recommends that the Australian Government

take steps to organise a number of industry forums for the purposes of

developing recommendations to strengthen the HVNL. Informed by the

recommendations of the roundtables, the government should then amend the HVNL

and thereby address the outstanding supply chain issues.

Recommendation 8

3.56

The committee recommends that the Australian Government convene a

series of industry-led roundtables to make recommendations to government on

ways to strengthen the Heavy Vehicle National Law.

Recommendation 9

3.57

The committee recommends that, informed by industry roundtables,

the Australian Government amend the Heavy Vehicle National Law to address

issues throughout the supply chain in the transport industry including chain of

responsibility, minimum payment terms of 30 days and electronic work

diaries.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page