Chapter 2

Background

Introduction

2.1

This chapter will provide a background to the inquiry including the

increasing use of military unmanned platforms, use of unmanned aerial vehicles

(UAVs) by the United States (US), the proliferation of UAV capability and ADF

use of unmanned platforms.

Terminology

2.2

While popularly referred to as 'drones', unmanned platforms are an area

of defence technology rich in acronyms and abbreviations. The range of terminology

has been increased by a differing focus on the unmanned vehicle/unit itself and

the associated systems of communication and control. In particular, the numbers

and categories of UAV (also referred to as remotely piloted aircraft (RPA) or

unmanned aircraft systems (UAS)) have soared in recent years. For convenience,

the term 'unmanned platform' has been used in the committee's report to refer

to all complex remotely operated devices and their associated communication and

control systems.

Unmanned platforms

2.3

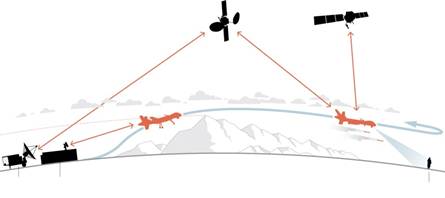

Unmanned platforms often have a number of common characteristics. These

include the structure of the platform itself, the external control system (such

as a ground control station), the communications system which links to the control

system, and the payload (which could include sensors or munitions). Automated

functions are also often incorporated such as waypoint navigation via GPS.

Figure 2.1. Visualisation of UAV communications.[1]

2.4

There are differing views on the first uses of unmanned platforms in a military

context.[2]

Notably, in the 1950s, the Australian Government Aircraft Factory produced

advanced 'target drones' (the GAF Jindivik) as part of an agreement with the

United Kingdom (UK) for guided missile testing. The Defence submission observed

that the popular term 'drone' may originate from the striped painted fuselage of

aerial targets.[3]

However, the first modern use of unmanned platforms is frequently identified as

the US use of the Ryan Fire Fly and Lightning Bug (Teledyne, US) high altitude

unmanned jets over South East Asia and North Vietnam in the early 1960s.[4]

These were target drones designs adapted for long range surveillance over

conflict zones.

UAV use by the United States

2.5

Since 2001, the US has attacked hundreds of targets in Afghanistan, Northwest

Pakistan, Yemen and Somali using armed medium altitude long endurance (MALE) UAVs

as part of counter-terrorism operations.[5]

Some of these operations have been criticised by human rights groups and others

in relation to their legality and the number of civilian casualties associated

with these attacks. For example, the Programme on the Regulation of Emerging

Military Technology (PREMT) submission notes that the 'rather extensive armed

UAV programme of the US has proven to be highly controversial, engendering

significant public debate in the US and provoking widespread discontent in the

countries in which the aircraft operate'.[6]

Statements by US President Barack Obama on 23 May 2013, at the National

Defense University in Washington, have been reported as signalling a shift

policy to reducing the number of armed UAV strikes conducted by the US.[7]

Proliferation of UAV capability

2.6

Australia, and many other developed countries, are partners to a number

of defence technology export regimes which can cover certain unmanned

platforms. For example, the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) is an

informal and voluntary association of 34 nations which seeks to coordinate

national export licensing efforts aimed at discouraging the proliferation of

unmanned delivery systems capable of carrying weapons of mass destructions.

Other countries such as Israel, India and China have indicated they will abide

by the rules of these defence export control regimes to varying degrees.

2.7

Nonetheless, advanced unmanned platforms (many capable of being armed)

appear to be proliferating. In the US, there has been internal debate about the

appropriate defence export controls on military UAVs.[8]

US sales of armed UAVs have been limited to the United Kingdom (UK), although

other countries have purchased large unmanned systems. On 17 February 2015, the

US State Department announced a 'new policy, governing the international sale,

transfer and subsequent use of US-origin military UAS' as part of a 'policy

review which includes plans to work with other countries to shape international

standards for the sale, transfer, and subsequent use of military UAS'. It

noted:

The new policy also maintains the United States'

long-standing commitments under the Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR),

which subjects transfers of military and commercial systems that cross the

threshold of MTCR Category I (i.e., UAS that are capable of a range of at least

300 kilometers and are capable of carrying a payload of at least 500 kilograms)

to a "strong presumption of denial" for export but also permits such

exports on "rare occasions" that are well justified in terms of the

nonproliferation and export control factors specified in the MTCR Guidelines.[9]

2.8

Under the new policy, the US will require recipients to agree to

principles guiding the proper use of US-origin military UASs:

Recipients are to use these systems in accordance with

international law, including international humanitarian law and international

human rights law, as applicable;

Armed and other advanced UAS are to be used in operations

involving the use of force only when there is a lawful basis for use of force

under international law, such as national self-defense;

Recipients are not to use military UAS to conduct unlawful

surveillance or use unlawful force against their domestic populations; and

As appropriate, recipients shall provide UAS operators

technical and doctrinal training on the use of these systems to reduce the risk

of unintended injury or damage.[10]

2.9

The development of cheaper UAVs suitable for intelligence, surveillance

and reconnaissance (ISR) has meant they have become available to almost all

modern militaries at the lower end of capability. Although the US, UK and Israel

are the main users of armed UAVs, other countries such as Russia, China, Iran, India,

South Korea and Taiwan, for example, have begun to develop increasingly

sophisticated unmanned platform capabilities. Other countries, including

Pakistan, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have

announced their intention to acquire them.[11]

Northrop Grumman commented:

In a global context, use of unmanned systems continues to

grow at a rapid pace – the last decade seeing an exponential increase especially

in UAS, primarily performing ISR missions, and with increasing use in command

and control, communications relay, battlespace awareness, force protection,

ordnance delivery and logistics.[12]

2.10

A Council of Foreign Relations report in 2014 on armed UAVs noted:

According to industry estimates, international interest in

armed drones has grown in the wake of Iraq and Afghanistan. The drone market is

expected to grow from [US]$5.2 billion in 2013 to [US]$8.35 billion by 2018. While

drones are still a relatively small portion of the overall defense market, the

segment with the "biggest potential" is the demand for

medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) drones, such as the Predator and Reaper.[13]

2.11

Increasingly, UAVs have been perceived as an important sovereign capability.

For example, in May 2015, Italy, Germany and France announced an agreement to commence

a MALE UAV development program. The German Defence Minister, Ursula von der

Leyen, was reported as commenting:

The goal of the Euro-drone is that we can decide by ourselves

in Europe on what we use it, where we deploy the Euro-drone and how we use it...

This makes us, the Europeans, independent.[14]

2.12

A recent report to the US Congress on military and security developments

in China has indicated that it was 'advancing its development and employment of

UAVs':

Some estimates indicate China plans to produce upwards of

41,800 land and sea-based unmanned systems, worth about [US]$10.5 billion,

between 2014 and 2023. During 2013, China began incorporating its UAVs into

military exercises and conducted ISR over the East China Sea...In 2013, China

unveiled details of four UAVs under development—the Xianglong, Yilong, Sky

Saber, and Lijian—the last three of which are designed to carry

precision-strike capable weapons.[15]

Stealth, combat and autonomy

2.13

Research and development in relation to large military UAVs appears to

have moved from focusing on platforms intended to operate in non-contested

airspace to platforms designed to operate in contested or denied airspace. The

focus on these types of unmanned platforms is arguably driven by advances in

the anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities of other countries. A2/AD

capabilities include anti-aircraft and anti-ship missile systems which could

potentially prevent aircraft and carrier fleets from approaching strategically

significant areas.

2.14

Some of these new unmanned platforms rely on low-observability, high

manoeuvrability, hypersonic flight and increased levels of autonomy from remote

operators. For example, the Taranis Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV) (UK Ministry

of Defence/BAE Systems) demonstrator incorporates stealth technology and is

designed for long range missions. The Taranis is described as having 'full

autonomy' elements.[16]

Similarly, the US Navy X-47B demonstrator (Northrop Grumman, US) is another stealth-focussed

UCAV platform designed to be launched from an aircraft carrier. This is one

design of the US Navy's Unmanned Carrier-Launched Airborne Surveillance and

Strike (UCLASS) program. As currently envisioned UCLASS UAVs will have 'deterministic

autonomy' within pre-set parameters such as decisions on when to conduct aerial

refuelling.[17]

China is also reportedly developing stealth-focused UAVs.[18]

Figure 2.2 Taranis UCAV demonstrator[19]

2.15

The line between unmanned platforms and guided munitions is also being

blurred. For example, the Harop (IAI, Israel) is a long range 'loitering

munition', controlled in-flight by a remote operator, designed to detect and

attack air defence radar systems by self-destructing into them. Similarly, the

Switchblade (AeroVironment, US) is an expendable small UAV equipped with an

explosive warhead which has been used by US Marines in Afghanistan.

Counter-UAV research focus

2.16

As unmanned platforms have proliferated as a component of military

arsenals around the world, research has increasingly focused on developing

effective counter-UAV technologies. Some commentators have highlighted that

small low-cost civilian 'drones' are already being utilised by non-State actors.

For example, on 17 March 2015, US Central Command noted an

airstrike by US and Coalition forces destroyed 'an [Islamic State] remotely

piloted aircraft' for the first time in Iraq.[20]

The RAND Corporation's report on UAVs commented:

The availability of this technology means it is likely that

states hostile to the United States will acquire it in the foreseeable future.

They could use it for suppression of internal enemies, or to support ground combat

units, the way the United States uses it today. This is not an insurmountable

threat to U.S. operations, but the United States is not yet prepared to deal

with it. Current U.S. doctrine for short-range air defense is primarily

concerned with defeating attacking helicopters with missiles. The United States

may have to develop new defensive systems as the threat from small UAVs

emerges.[21]

2.17

Similarly, the Sir Richard Williams Foundation has recently argued that

'defensive capabilities must also be developed in case such systems are used

against Australia and Australian forces'.[22]

2.18

In the US, there have been a number of recent developments in

counter-UAV research. Last year, the US Navy demonstrated a ship-mounted

directed energy weapon system, including against a UAV target.[23]

The US Joint Integrated Air and Missile Defense Organization has arranged a counter-UAV

demonstrator event focused on adapting existing and new air defence

capabilities to UAV threats.[24]

The US Army last year issued a 'request for information' on counter unmanned

aerial system capabilities. It observed:

US FORCES will be increasingly threatened by reconnaissance

and armed Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in the near and far future. These

threats can be employed against all echelons of US FORCES. These threats do or

may employ a variety of sensors and operate at a variety of tactical levels.

These levels include micro sized to large UAVs and operate with varying

altitude and speed.[25]

Increasing development of ground, surface and undersea vehicles

2.19

Research and development in relation to unmanned platforms is also

extending to unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), unmanned surface vehicles (USV)

and unmanned undersea vehicles (UUVs). This is illustrated by a number of

projects including:

-

the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has

funded the development of the Legged Squad Support System, a quadruped robot

which can be controlled by voice command and is designed to function as a

packhorse for troops;

-

the Guardium (IAI/Elbit, Israel) is a four-wheel medium size

surveillance UGV Force equipped with cameras, sensors and a loud speaker used

by the Israeli Defence for border patrol duties;

-

the Protector (Rafael, Israel) is a USV based on a rigid-hulled

inflatable boat which can be armed. The Protector has been deployed by the Israeli

Defence Force and Republic of Singapore Navy; and

-

the Remus (Kongberg, Norway) is a UUV remotely operated from a

laptop which has been used for mine clearance.[26]

Figure 2.3 Guardium

UGV[27]

ADF use of unmanned platforms

2.20

The ADF has previously used unmanned platforms in a number of contexts. However,

these utilisations have not involved the use of force. The Defence submission

noted that '[a] number of Defence Capability Plan (DCP) projects and other

projects are presently focused on unmanned capabilities; however, the DCP does

not currently contain a project to procure an armed unmanned platform or

system'.[28]

Unmanned Ground Vehicles

2.21

The Australian Army has used several UGVs mainly focused on explosive

detection and removal. For example, the ADF has purchased and utilised Talon

UGV in Afghanistan. This platform has been used for disposal of improvised explosive

devices (IEDs), reconnaissance, the identification of hazardous material and

combat engineering support. The Defence submission noted that 'Project Land

3025 is focused on investigating and procuring additional UGV or UAS to support

explosive ordnance search and disposal'.[29]

Unmanned Surface Vehicles

2.22

Defence outlined that the 'Navy does operate unmanned surface (on water)

vehicles (USV) in the Fleet training support role, where this capability is

focused on the reduction of risks to personnel and the provision of increased

training fidelity'. It described these USV capabilities as 'human-in-the-loop'

controlled.[30]

Unmanned Undersea Vehicles

2.23

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) Huon class mine hunters are equipped

with Double Eagle (Saab, Sweden) tethered remote operating vehicles, primarily

intended for the disposal of naval mines. The vehicle's payload can consist of

scanning sonar, echo locations, or self-navigation systems and have an extendable

manipulator arm which can be used to place a small explosive charge on a naval mine.

2.24

The Defence submission noted that Project SEA1778 'seeks to acquire

autonomous underwater vehicles for mine detection and classification,

expendable mine neutralisation systems for mine identification and disposal,

and unmanned surface vehicles for towing the in-service influence minesweeping

equipment'.[31]

It also stated that 'autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) systems have been used

for experimentation in hydrographic survey and clearance diving tasks'.[32]

Figure 2.4 – Double Eagle UUV[33]

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles

Tactical UAV

2.25

The ADF has used tactical UAVs to support operations in Iraq and

Afghanistan, in particular, the Skylark (Elbit Systems, Israel) and the RQ-11

Raven (AeroVironment, US). These are 'miniature' light weight short range UAVs which

are launched by hand and usually equipped to provide 'over the horizon' ISR. The

ADF has recently commenced training with the RQ-12 Wasp (AeroVironment, US).[34]

The Defence submission noted the RAN is presently reviewing options for a

small, tactical UAS to be employed in the provision of ISR for counter-piracy

operations.[35]

Figure 2.5 Skylark UAV launch[36]

Heron

2.26

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) currently operates the Heron UAV (IAI,

Israel) from RAAF Base Woomera for training purposes. Australia's Heron UAVs

completed more than 27,000 mission hours in Afghanistan and provided high

resolution ISR support to Australian forces and the International Security

Assistance Force in southern Afghanistan. Australia's Heron detachment in

Afghanistan flew its final mission for Operation SLIPPER from the Kandahar Air

Field on 30 November 2014. The Defence submission noted:

In October 2014, the former Minister for Defence announced

that Air Force would be returning a limited Heron-1 capability to Australia

following the end of its mission in December 2014. Australia will operate two

Heron-1 platforms in Australia to support the integration of complex UAS into

the Australian environment. The repatriation will also support the retention

and development of tactics and procedures for overland ISR gained during four

years of Heron operations in Afghanistan.[37]

Figure 2.6 – Heron UAV[38]

Shadow

2.27

The RQ-7 Shadow (AAI, US) tactical UAV has been used by the Australian

Army 20th Surveillance and Target Acquisition Regiment for reconnaissance,

surveillance, target acquisition and battle damage assessment. The Defence

submission noted the Shadow had been 'employed extensively in Afghanistan, has

been typically tasked in route reconnaissance, point reconnaissance and surveillance

flights to monitor "pattern of life" activities using sensors such as

electro-optic and infrared cameras. It stated that '[l]ike the United States

Army, the Australian Army utilises its soldiers to operate the Shadow 200,

which is different to the Australian Air Force, who employ qualified pilots to

operate the Heron-I'.[39]

2.28

The Defence submission outlined that the 'Joint Project (JP) 129 will

continue to support and update the Shadow 200 UAS capability as used in

operations in Afghanistan predominantly by ground forces' and 'the project will

also seek to procure small tactical UAS capabilities to support tactical ISR'.[40]

Figure 2.7 – Shadow UAV launch[41]

Triton

2.29

On 13 March 2014, the Prime Minister committed the Australian Government

to acquiring the MQ-4C Triton (Northrop Grumman, US) for use by the ADF. The

Prime Minister's media release noted that '[t]he total number of Triton UAVs to

be acquired and their introduction into service date will be further considered

by Government in 2016, based on the Defence White Paper'.[42]The

Tritons will be based at RAAF Base Edinburgh in South Australia and will

operate from the runway alongside the manned P-8A Poseidon maritime

surveillance aircraft when it enters RAAF service. The MQ-4C Triton will

operate alongside the P-8A Poseidon to replace the current AP-3C Orion

capability.

2.30

The Defence submission noted that the 'Triton is an unarmed UAS that is

capable of High Altitude Long Endurance (HALE) flight, as well as being

tactically agile to descend to medium altitudes as required' and will be fitted

with radar, electronic support and electro-optic sensors.[43]

Reaper training

2.31

The Defence submission stated:

Air Force is considering a program to fund the embedding of

ADF members into 'allied' UAS units. This activity will inform the ADF of the

support and operational characteristics of complex UAS systems, as operated by our

close allies, should the ADF seek to acquire similar systems in the future.[44]

2.32

On 23 February 2015, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for

Defence, the Hon Darren Chester MP, announced that the RAAF had commenced

training aircrew and support staff on MQ-9 Reaper (General Atomics, US)

operations in the United States. The media release stated 'the training program

provides a cost effective method to increase the ADF's understanding of complex

UAS operations and how this capability can be best used to protect Australian

troops on future operations'.[45]

At the April public hearing, Defence confirmed six RAAF personnel were

undertaking Reaper training in the US.[46]

Figure 2.8 – US Reaper UAV[47]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page