Chapter 1

Introduction

Referral of inquiry and terms of reference

1.1

On 24 March 2014, the Senate referred Australia's future activities and

responsibilities in the Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters to the Foreign

Affairs, Defence and Trade References Committee for inquiry and report by 28

August 2014.[1]

The reporting date was subsequently extended to 29 October 2014.[2]

1.2

The inquiry's terms of reference were as follows:

Australia’s future activities and responsibilities in the

Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters, including:

(a) Australia’s management and monitoring of the Southern

Ocean in relation to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing;

(b) cooperation with international partners on management and

research under international treaties and agreements;

(c) appropriate resourcing in the Southern Ocean and

Antarctic territory for research and governance; and

(d) any other related matters.

Conduct of the inquiry

1.3

The committee advertised the inquiry on its website and in the media,

inviting submissions to be lodged by 1 July 2014. The committee also wrote

directly to a range of people and organisations likely to have an interest in

matters covered by the terms of reference, inviting them to make written

submissions.

1.4

The committee received 23 submissions to the inquiry. The submissions

are listed at Appendix 1, and are available on the committee's website

at www.aph.gov.au/senate_fadt. Additional information, tabled documents and

answers to questions on notice received during the inquiry are listed at Appendix

2, and are also available on the website.

1.5

The committee visited Tasmania on 15-16 September 2014. On 15 September

the committee visited the Australian Antarctic Division's headquarters in

Kingston, and toured the ships Aurora Australis and RV Investigator at

Princes Wharf in Hobart. On 16 September the committee held a public hearing at

the Hobart Function and Conference Centre. On 26 September, a second public

hearing was held at Parliament House in Canberra. A list of the witnesses who

appeared at the hearings is at Appendix 3. The Hansard transcripts of

both hearings are available on the committee's website.

Structure of the report

1.6

The committee's report is in six chapters. Chapter 2 discusses the

international context for Australia's interests and obligations in the Southern

Ocean, and the key principles of Australian policy in the region. Chapter 3

examines threats posed by transnational crime and other illicit activities,

particularly illegal fishing, and Australia's response. Chapter 4 considers the

environmental importance of the Southern Ocean, scientific research issues, and

maritime mapping. Chapter 5 assesses present and proposed future resourcing for

Australia's activities in the southern waters, potential economic benefits, and

strengthening management and coordination to maximise the efficiency and

effectiveness of our engagement. Chapter 6 provides the committee's conclusion.

Background

Australia's maritime jurisdiction

in the Southern Ocean

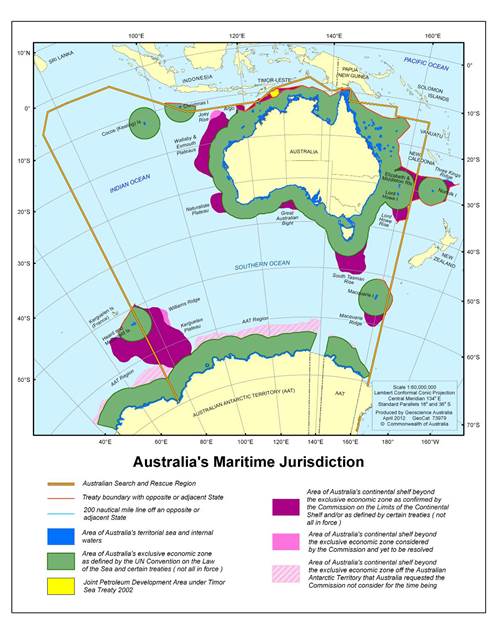

1.7

Australia's Antarctic and sub-Antarctic marine jurisdictions cover a

substantial geographic area, totalling more than five million square kilometres

and comprising some 30 per cent of Australia's entire marine jurisdiction.[3]

In addition to the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) and continental shelves

directly off Australia's southern mainland and Tasmania's coast, there are

several areas of Australian maritime jurisdiction further south.

1.8

Australia asserts sovereignty over approximately 42 per cent of the

Antarctic continent, known as the Australian Antarctic Territory (AAT), and

this extends to its adjacent offshore waters. Australia's sovereignty over the

AAT is not universally recognised, but under the 1959 Antarctic Treaty[4]

all sovereign claims in Antarctica are effectively suspended in time: no new or

expanded claims may be made while the Treaty is in force, and no act undertaken

by its parties can constitute a basis for confirming or disputing an existing

claim.[5]

In line with an established understanding among Treaty parties in this regard,

Australia exercises sovereign rights and takes responsibility for management of

this area, but enforces its domestic law in the AAT only against Australian

nationals.[6]

1.9

Australia exercises universally-recognised sovereignty over the Territory

of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI) in the southern Indian Ocean, and

over Macquarie Island in the sub-Antarctic Southern Ocean. HIMI is an external

territory of Australia, while Macquarie Island is part of Tasmania.

1.10 The HIMI territorial sea and EEZ lies mostly outside the jurisdiction of the

Antarctic Treaty, but falls within the larger area covered by the Convention on

the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention),[7]

and is treated as part of Australia's Antarctic jurisdiction for most purposes.

As a result of its sovereignty over HIMI and Macquarie Island, Australia also

enjoys exclusive rights to seabed resources in a vast area of extended

continental shelf in the Southern Ocean.[8]

© Commonwealth of Australia

(Geoscience Australia) 2012. This product is released under the Creative Commons

Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/legalcode

The Antarctic Treaty System and

other international agreements

1.11

The Antarctic Treaty System (ATS) provides the overarching international

framework for the governance of the land and waters south of 60° South latitude, an area which includes a

large portion of the Southern Ocean as well as the Antarctic continent itself,

and incorporates part of Australia's Antarctic marine jurisdiction.[9]

The Antarctic Treaty is the principal treaty of the ATS, and was negotiated

between its original 12 parties with the intention 'to ensure that Antarctica

would remain a place where science predominated and disagreements were resolved

peacefully'.[10]

Several other treaties have been added over the ensuing years to form the ATS,

key among them the CAMLR Convention, and the (Madrid) Protocol on Environmental

Protection and its annexes.[11]

The network of agreements comprising the ATS now governs many of the issues

that arise in the region and its waters, including prevention of conflict,

environmental protection, resource exploitation, fisheries management and

scientific research.

1.12

Australia was one of the original signatories to the Antarctic Treaty,

which now has 50 parties: 29 'Consultative Parties' who are actively engaged in

Antarctic research and are entitled to participate in decision-making under the

Treaty, and 21 'Non-Consultative Parties' who do not maintain stations in

Antarctica, but whose citizens may participate in scientific research.[12]

1.13

Beyond the ATS, various other international treaties also apply to Australia's

activities within the Antarctic marine area and in the greater Southern Ocean. Much

of the Southern Ocean is high seas, under which the various instruments and

doctrines of the international law of the sea apply. Notably, Australia is

responsible for coordinating search and rescue in a large portion of the

Southern Ocean, under the International Convention on Maritime Search and

Rescue[13]

and other treaties.[14]

The same sea area constitutes the Australian Security Forces Authority Area for

the purpose of International Maritime Organisation (IMO) security arrangements,

within which Australia is responsible for dealing with acts of violence against

ships.[15]

1.14

Bilaterally, Australia has concluded more than 15 memoranda of

understanding for policy, science and operational cooperation with other

nations in Antarctica and its waters, most of which are negotiated and managed

between the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD) of the Department of the

Environment and counterparts' Antarctic programs.[16]

Recent developments

20-year

Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan

1.15

The 20-year Australian Antarctic Strategic Plan (20 Year Strategic Plan)

was commissioned by the government in late 2013, and prepared by Dr Tony Press,

former Director of AAD and Chief Executive Officer of the Antarctic Climate and

Ecosystem Cooperative Research Centre (ACE CRC). Dr Press appeared as a witness

at the committee's public hearing in Hobart on 16 September.

1.16

The completed Plan was presented to the Minister for the Environment in July

2014, and publicly released on 10 October 2014. The Plan offered 35 recommendations

covering a broad range of aspects of Australia's role in Antarctica, including Australia's

strategic priorities, engagement in the ATS, scientific research, logistics,

government resourcing, coordination of activities, and maximising the benefits

of Antarctic work in Tasmania.[17]

The Plan's recommendations are listed at Appendix 4.

1.17

The Plan emphasised the importance for Australia of ensuring that the

ATS remained strong and stable and of investing in science, operations and

infrastructure to maintain Australia's place as a leading Antarctic nation. It

also made several recommendations for further work to establish Hobart as the

world's leading Antarctic gateway.

1.18

Upon the Plan's release, the government described it as 'a blueprint for

Australia's future engagement in the region'. The Hon Greg Hunt MP, Minister

for the Environment, said the government would consider the report in detail

and consult widely on its recommendations before providing a formal response in

the coming months.[18]

1.19

The key findings and recommendations of the Plan on matters covered by

this committee's inquiry are discussed further in the relevant sections of this

report.

Whaling

in the Southern Ocean

1.20

This inquiry also follows a landmark decision by the International Court

of Justice (ICJ) in relation to Japanese whaling in the Southern Ocean. In

2010, the Australian Government initiated legal action in the ICJ challenging

Japan's lethal whaling program. The case was heard by the court in 2013.

1.21

In its judgment, handed down on 31 March 2014, the ICJ determined that

the killing of whales under Japan's program could not be justified as being for

the purposes of scientific research as permitted under the International Convention

for the Regulation of Whaling (ICRW),[19]

and that Japan had not acted in conformity with various obligations under the

ICRW.[20]

The court did not outlaw altogether the use of "reasonable" lethal

methods for whale research, but stated its expectation that Japan would take

account of its reasoning and conclusions when considering whether to grant

future whaling permits.[21]

1.22

Following the decision, Japan indicated its intention to abide by the

judgment, and announced that it would conduct non-lethal research in the

Southern Ocean in the 2014-15 season, while redesigning its lethal whaling

program to resume in 2015-16.[22]

1.23

At the most recent International Whaling Commission (IWC) meeting held

in September 2014 in Slovenia, the Commission passed a non-binding resolution, proposed

by New Zealand and supported by Australia and others, requiring members to take

into consideration the ICJ decision in the development of its future scientific

whaling programs, and to put such programs before the full Commission for guidance

prior to their implementation. In response, Japan indicated that it did not

accept the terms of the resolution, and re-affirmed that it would re-commence 'scientific'

whaling in 2015.[23]

Australian

vessels

1.24

A number of key decisions in 2014 impact on the fleet of national

research, supply and patrol vessels available to Australia for use in the Southern

Ocean and Antarctic waters.

1.25

Australia's dedicated Antarctic research and supply 'icebreaker' ship,

the Aurora Australis, is managed by the AAD. The Aurora Australis

is an aging vessel due to retire, and discussions have been under way for some

years regarding its replacement. The government announced in the 2014 Budget

that the commissioning of a replacement vessel would proceed, and the Minister

for the Environment subsequently announced that two companies had been

shortlisted to tender for the construction of the new vessel. A contract with

the successful tenderer is to be signed in late 2015, with the new vessel

expected to be ready for operation in October 2019.[24]

1.26

The CSIRO Marine National Facility operates a vessel equipped and

dedicated to the conduct of scientific research in Australian and surrounding

waters. Following the retirement of the previous vessel, the Southern

Surveyor in 2013, the new RV Investigator arrived in Hobart in

September 2014. Assessment of research proposals and technical preparations are

now taking place for the ship to commence active deployment from 2015.

1.27

The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS)

maintains only one vessel with the capacity to patrol the ice-prone areas of

the Southern Ocean. The most recent vessel, ACV Ocean Protector, was

decommissioned in mid-2014. In its place, ACBPS has commissioned the

ice-strengthened Australian Defence Force (ADF) vessel, the ADV Ocean Shield,

which will ultimately be transferred to the management of ACBPS. The Ocean

Shield is a sister ship to the Ocean Protector, so

essentially identical in its capabilities, and is the only vessel in the border

protection fleet with the range, endurance and sea and ice capability to

operate in the Southern Ocean.[25]

Like the Ocean Protector before it, the Ocean Shield will be

allocated to meet all of Australia's border protection and humanitarian

response needs as required, on a priority basis. In fact, due to competing

priorities in Australia's northern waters, the Ocean Protector had

conducted no patrols in the Southern Ocean since February 2012.

1.28

The ACBPS is also in the process of acquiring eight new Cape

class patrol vessels, however, these are not suited for operations in the

Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters.[26]

1.29

For its part, the ADF has little capacity to operate in the

Southern Ocean. The navy possesses one ice-strengthened vessel with limited

capability to operate in light ice (HMAS Choules), but the

remainder of the fleet is not well suited to operate in sub-Antarctic waters.

The Air Force has aircraft with the range to operate in the region, including

the AP-3C Orion patrol plane and the C-17A Globemaster transport aircraft, but

competing demand for these assets is high. The Department of Defence advised

the committee that while the ADF was acquiring new capabilities which may have

the ability to work in the Southern Ocean region, they had not been acquired

specifically with that environment in mind, and 'the extent to which they are

able to do so will depend on the threat environment and other demands on their

capability.'[27]

The

2014 Budget

1.30

Significant controversy surrounded the impact of the 2014 Federal Budget

on Australia's scientific, operational and other work in the Antarctic region. The

government highlighted new funding in support of Australia's leadership as an

Antarctic nation as one of the flagship outcomes of the budget, drawing

attention to the commitment to procure a new icebreaker as a major

demonstration of its commitment to both Tasmania and Antarctica.[28]

Other new initiatives announced in the budget were $24 million over three years

for a new Antarctic Gateway Partnership for scientific research between AAD,

the University of Tasmania and CSIRO (to be administered by the Australian

Research Council), $25 million over five years for the continued work of the Antarctic

Climate and Ecosystems Cooperative Research Centre (ACE CRC), and $38 million

to upgrade Hobart airport.[29]

1.31

In addition, the government announced an additional $45.3 million to

support the Antarctic airlink, $13.4 million for logistics support, and $9.4

million for the maintenance of Australia's Antarctic bases.[30]

1.32

At the same time, core budget and staffing cuts to the Department of the

Environment, CSIRO and other agencies and programs were severe, and expected to

compromise Australia's ability to maintain its scientific and operational

activities in the region.[31]

The annual appropriation to the Department of the Environment for its Antarctic

program was cut from $136.4 million in 2013-14 to $107.8 million in 2014-15,

with a further $17.8 million to be cut over the four-year forward estimates.[32]

This formed part of an overall foreshadowed $100 million cut to the Department

of the Environment's core budget over four years, which it was expected would

lead to the loss of around 670 jobs department-wide.[33]

1.33

For its part, the CSIRO was facing the biggest cut to its budget in

recent memory. While $65.7 million was allocated over four years for the

operation of the new research vessel RV Investigator, core funding was

cut by $27 million in 2014-15 as part of $111.4 million in direct reductions over

the four year estimates, with the additional loss of an efficiency dividend of

$3.4 million.[34]

It was widely reported that CSIRO would lose more than 500 positions, including

significant losses from its marine and atmospheric research areas.[35]

Acknowledgements

1.34

The committee thanks all those who contributed to the inquiry by making

submissions, providing additional information and appearing at the public

hearings. The committee is also grateful to the staff of AAD and CSIRO who facilitated

and hosted its site visits in Tasmania.

Note on references

1.35

References to the committee Hansard are to the proof Hansard. Page

numbers may vary between the proof and the official Hansard transcript.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page