Chapter 11 - Australia's public diplomacy: Training and practitioners

11.1

Most countries now consider public diplomacy a serious business with

some looking to specialists in private enterprise to help them with their

public diplomacy programs.[1]

Participants in a recent international conference in Geneva examining the

challenges for foreign ministries believed strongly that traditional training

methods were 'no longer enough' for diplomats. They recognised that one of the

growth areas in training included public diplomacy.[2]

In looking specifically at the diplomat assigned abroad, they recognised that

one of the key tasks was 'to create understanding for the home country' which

required the capacity to reach out to people in the host country, 'connecting

with the active publics'. They concluded that a diplomat abroad is no longer

the principal negotiator, nor the key interpreter of home policy:

His main business is not so much with the foreign ministry in

the receiving country as with the entire political class; he needs a dense and

stable network of contacts. Personal communication skills and language ability

are vital.[3]

11.2

In this chapter, the committee looks at the role and function of the Images

of Australia Branch (IAB) as the unit within DFAT that manages and coordinates the

department's public diplomacy programs. It examines how effectively public

diplomacy is integrated into the mainstream of DFAT's work and the role of the

IAB as the main coordinator for the department's public diplomacy. The committee

looks at where this unit is located in the department, the staff dedicated to

public diplomacy, and IAB's role in training and preparing staff for public

diplomacy activities. The committee also considers the skills required in an

effective public diplomacy practitioner and whether DFAT should have a unit of

public diplomacy specialists.

Coordinating public diplomacy activities within DFAT

11.3

DFAT has primary responsibility for implementing Australia's public

diplomacy programs. In September 2003, DFAT announced a series of initiatives

to integrate public diplomacy work more closely into the mainstream of the

department's activities.[4]

In its evidence to the committee, the department said that in 2005–06 it had a team

of public diplomacy specialists and a staff of 229 dedicated to public

diplomacy work.[5]

They are distributed throughout the department as set out in the following

table provided by DFAT.

Table 11.1: Public Diplomacy staff in 2005–06[6]

|

Division

|

Total

|

|

Americas Division

|

1.2

|

|

Australian Passport Office

|

6.5

|

|

Corporate Management Division

|

5.0

|

|

Consular Public Diplomacy and Parliamentary Affairs

Division

|

23.7

|

|

Economic Analytical Unit

|

7.0

|

|

Europe Division

|

2.3

|

|

Executive Planning and Evaluation Branch

|

1.5

|

|

Global Issues Branch

|

2.0

|

|

International Organisations and Legal Division

|

3.9

|

|

International Security Division

|

5.8

|

|

North Asia Division

|

6.0

|

|

Office of Trade Negotiations

|

2.7

|

|

Pacific Division

|

3.4

|

|

South-East Asia Division

|

2.9

|

|

South and West Asia Middle East Africa Division

|

2.2

|

|

Trade Development Division

|

5.6

|

|

Free Trade Agreement Taskforces and Unit

|

1.0

|

|

Asia Pacific Economic Co-operation Taskforce

|

0.5

|

|

State offices

|

13.0

|

|

Posts – Europe

|

5.2

|

|

Posts - Middle East & Africa

|

4.4

|

|

Posts - New Zealand & South Pacific

|

4.0

|

|

Posts - North Asia

|

3.4

|

|

Posts - South & South East Asia

|

8.6

|

|

Posts - The Americas

|

5.2

|

|

Posts – Locally Engaged Staff (LES)

|

102.0

|

|

Total

|

229.0

|

11.4

For the purposes of this report, the committee concentrates mainly on

the IAB which manages the department's internationally focused public diplomacy

programs and coordinates overall public diplomacy activities. The IAB is

located within the Consular, Public Diplomacy and Parliamentary Affairs

Division of DFAT.

11.5

According to Dr Strahan there are 'about 16 or 17 people' in IAB. The

economic analytical unit, the trade outreach area and the secretariats

servicing the bilateral councils also employ a number of officers involved in

public diplomacy activities. He indicated that there may also be 'a couple of staff'

working on the public diplomacy side of important issues such as counter-terrorism

and counter-radicalisation. He explained that the remainder of public diplomacy

staff tend to be located at overseas posts.[7]

Public diplomacy a part of

mainstream work

11.6

Dr Strahan informed the committee that in recent years DFAT had decided

to 'much more closely integrate public diplomacy work with the work' of other

sections in the department. In his view, the distribution of staff engaged in

public diplomacy within the department demonstrates the extent to which

mainstream public diplomacy activity is integrated into the department in

general. He stated:

At some point public diplomacy can be seen as being a little bit

to the side of mainstream work in a foreign ministry. That is not the case in

our service. All of our officers are expected to take public diplomacy

seriously and to see how it fits into their normal foreign policy and trade

work.[8]

11.7

He gave the example of 11 newly recruited media specialists:

We do not want these specialists to feel like they are part of a

separate stream, that they are a subspecies which is different from the rest of

the department. They must feel very much that they are officers who can be

deployed to other positions later in their careers which might be more

traditional policy or diplomatic positions where they will continue to draw on

their specialist skills. Sometimes they might have a more specialist position,

but they are very much part of the general cohort of skilled people in the

department.[9]

11.8

A number of witnesses before the committee commented on DFAT's approach

to making public diplomacy an activity central to the department's work.

Mr Jacob Townsend, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, was of the view that

the 'mainstreaming of public diplomacy activities throughout DFAT placing

emphasis on it in staff training and general staff awareness was a good idea'.[10]

He agreed that it was important for DFAT staff to appreciate that public

diplomacy was an important part of their work. Mr Freeman also defended

strongly DFAT's policy of streaming and mainstreaming and getting public

diplomacy 'to be very much an integral part of the way the department works'.[11]

11.9

Although some witnesses approved of DFAT's approach to making public

diplomacy a mainstream function of the department, they nonetheless were

critical of, or could see scope for improving, DFAT's public diplomacy efforts.

For example,

Mr Townsend expressed concern about the professional value placed on public

diplomacy in DFAT. He quoted from DFAT's submission that 'In 2006, IAB launched

a new PD training course for staff proceeding on overseas postings. This course

will become mandatory in 2007 for all staff appointed to positions with a

significant PD content'. He interpreted this statement to mean that:

...there is a differentiation between staff who have a PD role and

staff who have less of a PD role. That suggests also that therefore you are

not mainstreaming in a comprehensive way; you are suggesting to people vaguely

that public diplomacy is a responsibility but you are not reinforcing it.[12]

Committee view

11.10

The committee notes Dr Strahan's comments about the high value that DFAT

places on integrating public diplomacy into the mainstream of its work. The committee

agrees with this policy. The committee believes, however, that DFAT must ensure

that its stated policy of public diplomacy as an integral part of mainstream

diplomacy is supported by action that clearly demonstrates that public

diplomacy is a highly valued activity in the department.

The role of IAB in training staff

and coordinating public diplomacy activities

11.11

To ensure that the department's public diplomacy activities continue to

reflect Australia's foreign and trade objectives, the IAB conducts regular

reviews. It holds annual consultations with staff from the department's geographic

and subject expert areas and six-monthly budget reviews. Furthermore, in June

2005 it produced its Public Diplomacy Handbook and in July 2006 its Public

Advocacy Techniques.

11.12

DFAT also explained to the committee that new graduates, who provide the

main source of recruitment and go on to do mainstream policy and corporate work,

receive a briefing session about the department's general public diplomacy

programs. Dr Strahan explained:

We then have a program where we take them around to a number of

different stakeholders who contribute to the overall public diplomacy effort.

For instance, they will meet with Australia Network and the Australia Council.

That is our front-line moment where we first communicate with our new staff and

make sure that they understand the importance of public diplomacy. We then have

a series of rolling training programs, which run throughout the year, including

a relatively new pre-posting training course specialising in public diplomacy.

We have a series of what we call advocacy workshops which run every year and

have been doing so for some time. Those advocacy workshops will pick up on key

issues of the moment, so we will judge, in consultation with other parts of the

department, what issues would warrant a dedicated public diplomacy advocacy

training session. We have just had a series of those in the last couple of

weeks and we will have more across the year.[13]

11.13

The IAB also maintains close contact with overseas posts and works with them

to ensure that their work is consistent with the government's public diplomacy

goals.

Overseas posts

11.14

The department currently runs funded public diplomacy programs in 85

locations overseas. In 2005–06, Australian overseas posts held more than 3000

public diplomacy activities for a total annual budget of $1.6 million. The

activities ranged from public advocacy campaigns, including a joint

Indonesia–Australia public information campaign on illegal fishing, to major

cultural events to the mainstay of public diplomacy such as speeches, media

releases, seminars, conferences, cultural promotions, exhibitions and displays.[14]

Staff working on public diplomacy at

overseas posts

11.15

Clearly, Australia's overseas posts form an integral part of DFAT's

public diplomacy network. Dr Strahan explained that there is a range of people

at post doing public diplomacy work. He stated:

We have five full-time positions overseas which are PD dedicated

and then there will always be an A-based officer in each mission who spends a

varying proportion of their time on public diplomacy. In some cases that might

be 10 or 20 per cent. This is where the fractions come in. That is why we have

half people or people that work part-time. [15]

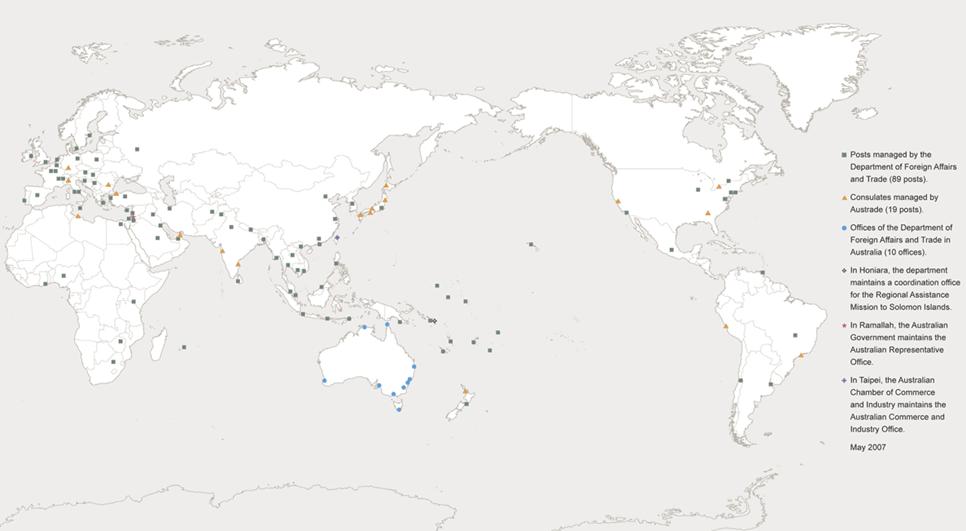

Department of Foreign

Affairs and Trade—Posts, Consulates and offices.

11.16

He informed the committee that the department has two A-based officers,

who work full time on public diplomacy, in Jakarta, one in Beijing, one in

Tokyo, and one in Washington and that these positions had been in place for

'many years'.[16]

11.17

Mr Kirk Coningham, former DFAT officer, accepted DFAT's argument that the

maintenance of Australia’s diplomacy demands an expensive and elaborate network

of overseas missions. He also agreed with the view that 'to do diplomacy well

it must be done on the ground'. He went on to state that:

But when you look at the public diplomacy resources on the

ground, you come up with a pretty sorry picture. In its evidence to this committee

DFAT admitted that in the vast majority of posts it is 10 to 20 per cent of the

responsibility of a normally junior DFAT officer. That is a day or so a

fortnight. The reality at post is that the function is performed by locally

engaged staff.[17]

11.18

The committee notes that table 11.1 provided by DFAT to the committee records

an equivalent of only 30.8 A-based staff working on public diplomacy at Australia's

overseas posts and 102 locally engaged staff (LES).

Training for, and coordinating,

public diplomacy activities at overseas posts

11.19

DFAT maintained that it has incorporated public diplomacy activities

into the work of all its posts. Dr Strahan referred to the new pre-posting

training courses that focus on public diplomacy. He noted further that:

A number of other agencies pointed out that they do not attend

our pre-posting PD training courses. That has been a slip on our part. We will

now invite all officers from all agencies who are going on posting to attend

these courses so that they can understand the public diplomacy dimension of their

work.[18]

11.20

Also, under an initiative announced in 2003, IAB conducts a more regular

and systematic program of regional public diplomacy workshops for posts. DFAT

advised the committee that these workshops are intended to 'provide an

opportunity for face-to-face discussion, mentoring and revision to Post PD

programs'.[19]

The department recently held regional public diplomacy workshops in Shanghai, Hanoi

and Brisbane to help posts integrate their public diplomacy activities more

closely with key foreign and trade policy objectives.[20]

Dr Strahan explained:

We get our posts from one particular region and we pull them

together for two days and systematically go through all of our different public

diplomacy and cultural diplomacy programs. That is the venue for our posts to

communicate with us and let us know what is confronting them at the coalface of

public diplomacy overseas and it is a chance for us to communicate with them

new things that we are introducing back home.[21]

11.21

As noted previously, IAB publishes a public diplomacy handbook which is

used as a guide for Heads of Mission to ensure that public diplomacy activities

are closely linked with the government's key policy objectives. The handbook is

intended to offer practical advice for posts 'to advance Australia's foreign

and trade interests, highlight areas where Australia excels and dispel

potentially damaging misconceptions'.[22]

To this end, it emphasises that before holding any event, posts should 'clearly

identify the message, target audience and most effective means of delivery'.

Moreover, these events should be part of a post's annual public diplomacy

strategy.

11.22

Indeed, posts are required to prepare public diplomacy strategies and

programs. According to DFAT, the strategies include 'a description of the

post's operating context, identification of resources including opportunities

for partnerships in public diplomacy projects, the post's key objectives, means

to secure these objectives, major platforms available for activity and

performance indicators'. Dr Strahan used the European posts as an example of

the steps taken to ensure that posts are in touch with one another and aware of

the broader public diplomacy objectives:

What we first do is set an overarching PD strategy which covers,

in this case, the entire European region where we clearly have a number of core

objectives. Under that umbrella, each post has to transform that general PD

strategy into a country-specific strategy. Sometimes particular parts of the

overall strategy might be more relevant to one country or another. They then

have to have very tight, good and concrete objectives which are strategic in

nature, which they then have to report against.[23]

Locally engaged staff

11.23

Dr Strahan also noted that locally engaged staff employed at overseas

posts have a significant role in Australia's public diplomacy programs. Mr Coningham,

however, questioned their capacity to perform public diplomacy on behalf of Australia.

Aside from professional qualifications, discussed later in this chapter, Mr Kirk

Coningham raised another concern about the heavy reliance placed on locally

engaged staff to prosecute a post's public diplomacy activities. He would effectively

discount locally engaged staff as a vital component of public diplomacy

conducted by overseas posts because:

...they cannot read the cables and they are not at the

policy-making table. In fact, it would be unkind to them as foreign nationals

to allow them to see the skeletons that Australia may have or the negative

issues with which we are trying to deal in that country. We are basically

stripped of a professional capacity to do that in all but our top three posts.[24]

11.24

He emphasised that, in his view, 'If you are not at the policy table—if

you are not reading the cables—you really do not know what is going on'. [25]

The International Public Affairs Network also commented on, what it regarded

as, restrictions that limit the ability of locally engaged staff to contribute significantly

to public diplomacy:

Non-nationals have little firsthand knowledge or experience of

the country they are promoting, and little capacity to turn the Australian

Government’s objectives into effective public diplomacy strategies. Few locally

engaged Australian expatriate staff, if any, can be expected to have the levels

of security clearance needed to function effectively as members of a diplomatic

mission’s senior management team.[26]

11.25

In response to these observations about locally engaged staff, Dr

Strahan informed the committee that the locally engaged staff are not isolated

or treated as separate from embassy staff: that they are 'very much part of an

integrated team'.[27]

He pointed out that locally engaged staff cannot attend some meetings because they

do not have the appropriate security clearance. He underlined his previous

point, however, about the department's endeavours to achieve 'the right balance

and integration' between specialists and locally engaged staff'. He then noted

that there is always an A-based officer responsible for public diplomacy who

would lead the public diplomacy team. He explained that it would be incumbent

upon such an officer to be a conduit between the locally engaged staff and

those attending restricted meetings. He stated further that the 'vast majority

of public diplomacy' work is unclassified.[28]

11.26

Dr Strahan then commented on the training of locally engaged staff. He

advised that, they attend DFAT's regional public diplomacy workshops on the same

footing as A-based officers. He also mentioned that DFAT has an LES leadership

program which is open to LES in general. Under this program, groups of LES

visit Australia at regular intervals and that frequently public diplomacy staff

attend. He referred again to their career status but also noted the advantage

of having local knowledge:

There will be media officers, cultural officers or public

relations officers. Some posts at various points have had events managers. It

is a good way of building together good local knowledge, because the local staff

should also understand the country that we are working in. They have the

relevant qualifications and then they work with A-based officers who come armed

with a firm understanding of what we do.[29]

Committee view

11.27

The committee notes the concerns that locally engaged staff, who have a

significant role in a post's public diplomacy, may not be privy to communications

or discussions relevant to their area of responsibility and whose knowledge of Australia

may limit their ability to carry out their duties effectively. The committee

understands that DFAT has in place training programs designed to mitigate some

of these problems. Even so, the committee believes that if public diplomacy is

to be accepted as a mainstream activity, the department should review the staffing

arrangements of their posts to ensure that public diplomacy is not relegated to

junior officers or locally engaged staff but is a high priority for all staff

who should have the appropriate training.

11.28

In turning to the role and functions of the IAB, the committee welcomes

DFAT's endeavours to make public diplomacy a mainstream activity in the

department. It notes the work that IAB undertakes to ensure that public

diplomacy is integrated into the work of other sections in the department; that

the rest of the department is aware of the importance of public diplomacy; that

their activities are consistent with Australia's public diplomacy goals and

where possible are complementary.

11.29

On a number of occasions in this report, the committee has highlighted

the importance of public diplomacy especially as an exercise of soft power. An

effective public diplomacy strategy is critical to the overall endeavours of

the department to tackle effectively some of Australia's greatest foreign

policy challenges, such as the threat of terrorism and developments in the

South West Pacific. The committee believes that, if the IAB is to perform its

important role in the formulation, coordination and implementation of Australia's

public diplomacy, it must assume a prominent position in the department and be

well supported with resources.

11.30

To ensure that the department is able to meet the growing challenges of

conducting an effective public diplomacy policy, the committee believes it

would be timely for DFAT to conduct or commission an independent survey of its

overseas posts to ascertain their needs when it comes to public diplomacy. The

survey would cover issues such as training and resources available for public diplomacy,

access to specialists in public relations and the media and the effectiveness

of IAB in meeting the needs of posts in carrying out their public diplomacy

activities. As an example, the United States General Accounting Office

administered a survey to the heads of public affairs sections at US embassies

worldwide in 2003. It identified a number of problems including insufficient

resources and time to conduct public diplomacy effectively as well as

inadequate training in public diplomacy skills.[30]

Recommendation 15

11.31

The committee recommends that DFAT conduct an independent survey of its

overseas posts to assess their capacity to conduct effective public diplomacy

programs. The survey would seek views on the effectiveness of the post's

efforts in promoting Australia's interests, and how they could be improved, the

adequacy of resources available to conduct public diplomacy activities, the

training and skills of staff with public diplomacy responsibilities, the

coordination between agencies in public diplomacy activities; and the level of

support provided by IAB and how it could be improved.

11.32

The survey would also seek a response from the overseas posts on

observations made by the educational and cultural organisations, noted by the committee

in this report, levelled at the delivery of Australia's public diplomacy

programs. Such matters would include suggestions made to the committee that

public diplomacy opportunities are being lost in the absence of effective

mechanism for the coordination of activities. See paragraphs 7.24–7.34 (alumni

associations); 9.22–9.30 (cultural organisations); 9.41–9.44 (educational

institutions); 10.23–10.39 (Australia's diaspora).

Practitioners of public diplomacy—skills and training

11.33

There were a number of witnesses who argued that public diplomacy

requires practitioners who are specially trained for this work. Mr Geoff Miller

identified the 'need for specialised staff able to understand, manage and add

value to the expanding international agenda and to deal with the increased

number of actors, despite resource constraints'.[31]

The International Public Affairs Network also argued that there was the need

for specialists in public diplomacy:

Australia’s voice is merely one among many clamouring for

attention in an increasingly noisy international public communication

environment. Only specialists in the category of public relations and

organisational communication known as public diplomacy can best achieve Australia’s

objectives in this highly competitive field.[32]

11.34

It contended that 'the highest rates of success in public diplomacy are

achieved by people with the necessary specialist skills and experience from the

realm of the mass media and public relations, as well as specialist team

structures and resources managed by specialists with whole-of-government

guidance'.[33]

It stated:

In practice it requires the skills of communication analysis,

planning, management, procurement, writing, design, multimedia production,

marketing and dissemination. These skills do not belong to the profession of

diplomacy, but to the profession of public relations and communication.

Therefore, ‘public diplomacy’ in its full sense is public relations—or

more precisely, a category under public relations, government international

public affairs.[34]

11.35

Developing this argument, Media Gurus also focused on the need for specialists

in public diplomacy within the government:

...it needs to be recognised that while bureaucrats have many and

varied skills in the Australian Public Service, the particular skills of public

diplomacy do not automatically come with promotion to higher office.

Strategic thought related specifically to strategic

communication can only come by way of intense training, in an environment where

that training yields specific outcomes in partnership between organisation and

officer: i.e. training needs to be looked at as a process with clearly

negotiated outcomes: ‘if I train in this and do well and meet milestones, I can

[expect] to benefit in the following specific ways’. It should be viewed by the

same criteria as performance related pay.

Additionally, serious consideration needs to be given to having

more specialist communicators and PD practitioners attached to departments and

agencies that have international promotional responsibilities.[35]

11.36

Mr Kirk Coningham stated that the 'traditional diplomacy' exercised by

DFAT officers 'does not include public diplomacy'.[36]

He maintained that 'expertise encompassed in training, education and experience

is an absolute prerequisite for doing public diplomacy correctly, and fulsomely'.[37]

11.37

Mr Chris Freeman, a public affairs practitioner with extensive

experience in Australia's public diplomacy policy programs, was of the view

that DFAT no longer has the capacity to undertake 'sustained long-term multimedia

communication strategies'. He noted further that at a time when the importance

of public diplomacy is recognised, Australia no longer has 'the kinds of

resources' it used to have.[38]

He stated:

I do believe that we need to boost the number of specialist

communications staff dedicated to PD work. I do not think we can make a lot

more progress without that. You need to use these specialists to develop and

implement strategic, sustained, multimedia advocacy and information campaigns.

You need then to integrate them into the policy-making elements of government

as well and not let them languish in isolation.[39]

11.38

Dr Strahan acknowledged that there has been a continuing debate about

'generalist' versus 'specialist'. He stated that DFAT monitors its mix of skills

and 'regularly refreshes its skills base' to ensure that it has the mixture of skills

necessary to deliver the required results. Indeed, he referred to the

recruitment of 11 media specialists over the previous year.[40]

He told the committee:

...we now have journalists working through the organisation who

will be doing different kinds of jobs. They came to the organisation with that

journalistic background. They might end up doing one of our jobs which is a

more mainstream exact media position, but a lot of them end up doing other

things. That is what we want. We want that two-way interchange between people

who have more specialist skills and people like me who joined the department

with a PhD in history—a very different kind of background—who can work together.[41]

11.39

Dr Strahan also explained that LES are appointed specifically for public

diplomacy functions and that at least half of their duties involve public

diplomacy activities.[42]

According to Dr Strahan, the preliminary findings of a recent stocktake

involving 56 of Australia's 86 posts provided 'a fairly good snapshot of the staff'

that DFAT have recruited as locally engaged public diplomacy people. It found a

significant number of staff with journalism, communications, public relations,

media studies or cultural studies qualifications; others held humanities

degrees, while some had languages and linguistics qualifications or other qualifications

which were relevant, such as marketing or commerce. He stated:

When we looked at where these people had previously worked, we

found that 22 of them had previously worked in public relations, communications

or event management; 20 had worked in the media; 13 had worked in marketing;

and so forth.[43]

11.40

In his view, the results of the survey were reassuring because it

demonstrated that DFAT had recruited the 'right kind of people'. He noted that

'Sometimes they might be Australian citizens who live abroad, but they have the

right qualifications, they have the right experience and then they work in

tandem with the A-based officers at the post'.[44]

In May 2007, he informed the committee that the survey of posts was almost

complete and confirmed initial findings cited above. Of the 127 locally engaged

staff currently working on some aspect of public diplomacy, '50 have

qualifications in journalism, communications, public relations, marketing or

other media qualifications; 26 have humanities degrees; 20 have degrees in law,

politics and international relations; and 13 have degrees in commerce'.[45]

Committee view

11.41

The committee recognises that DFAT faces a major challenge ensuring that

it has the skills set necessary to deliver effective public diplomacy,

including highly developed communication and public relations skills. Although

all DFAT officers should be skilled in the art of public diplomacy, the committee

accepts that not all can be trained specialists in the area of communications

and public relations.

Call for a specialist public

diplomacy unit

11.42

A number of witnesses not only highlighted the need to have skilled

public diplomacy practitioners but supported proposals for the establishment of

a public diplomacy unit staffed by specialists. They drew particular attention

to the loss of expertise and specialists in public diplomacy when the

International Public Affairs Branch within DFAT was abolished in 1996. The

International Public Affairs Network argued that this organisation, which had

responsibility for Australia's public affairs and information activities, had

given Australia an edge in public diplomacy for 57 years.[46]

It stated that Australia 'must rebuild and relaunch its international public

affairs capacity within a specialist organisation focused on

whole-of-government public diplomacy'.[47]

11.43

Mr Kirk Coningham referred to the loss of the entire international

public diplomacy specialists in 1996 which, in his words, 'stripped' DFAT of

public diplomacy expertise and Australia of public diplomacy ideas.[48]

He stated:

By removing the expertise from the Department of Foreign Affairs,

we removed the font of ideas around public diplomacy and what it can really

achieve. I think that was the terrible tragedy of the time. Where it has left us

now is in a situation where we have a press release or a travelling exhibit or

an Australia Day party—and, in great stock, that is our public diplomacy.[49]

11.44

Mr Trevor Wilson also referred to the 'old days' when, in his view, DFAT

had a number of specialist journalists and the Australian government had that

'institutional capacity'. He too suggested having an institutional unit of

specialised people who could provide the specialist knowledge, particularly to

overseas posts. He noted:

The corporate support that they [overseas posts] get is not

necessarily going to be all that helpful unless there is some kind of...store of

knowledge and expertise and information back in the department that can give

you this...It seems to me that we are now in a situation where we have to respond

much more on a short-term basis because some of the longer term messages do not

seem to be getting out there. I agree that an institutional unit would be some

kind of answer to that.[50]

11.45

In responding to the proposal for a specialised coordinating unit, Mr Freeman

noted that this organisational structure should be 'plugged in very closely

with the major policy-making areas of government as well'.[51]

Committee view

11.46

The committee notes the benefits for public diplomacy in having specialist

staff skilled in communications and public relations that are available to

offer advice, guidance, to train and educate other staff in public diplomacy

matters, or in some cases, to devise, manage or even deliver a public diplomacy

program. The committee, however, does not believe that a specialist unit is

required.

11.47

Although, the committee does not support the creation of a unit of

specialists in public diplomacy, communications and public relations, it does

see a very clear need for the department to ensure that it has the correct

balance of specialists and generalists engaged in Australia's public diplomacy.

It is important for public diplomacy to be seen as a mainstream activity and

not the reserve of specialists located in a separate unit.

11.48

Developments in technology also have implications for staffing and the

training requirements of DFAT officers with regard to public diplomacy. The

following chapter considers the challenges that modern technology presents for

Australia's public diplomacy.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page