Addressing SG non-compliance

The ATO's effectiveness in identifying and addressing SG non-compliance

6.1

The ATO informed the committee that in 2015-16, ATO compliance action

resulted in:

-

$670.4 million SG charge raised (including penalties and interest);

-

$341.3 million SG charged collected;

-

2997 default assessments raised; and

-

877 Director Penalty Notices issued for SG debt of $130 million.[1]

6.2

The ATO conducts audits and reviews to ascertain SG non-compliance.

Approximately 70 per cent of the cases the ATO looks into arise from employee

notifications, with the remaining 30 per cent of cases stemming from ATO

initiated strategies.[2]

6.3

The ATO's compliance program is comprised of three review or audit

types:

-

Employee Notification (EN) cases;

-

ATO initiated cases – SG Proactive; and

-

ATO initiated cases – Employer Obligations.[3]

6.4

As the ATO stated in its submission:

The majority of our review and audit work is directly

addressing employee notifications. We also undertake ATO initiated reviews and

audits arising from case selections from high risk employers or from high risk

industries. We also examine SG payments when reviews and audits are undertaken

examining income tax employer obligations risks.[4]

6.5

The ATO's submission notes that over the past three years, the ATO has

increased its efforts to select cases from a broader array of sources other

than EN. The submission also notes that the ATO takes a risk differentiated

approach to compliance activities which considers factors such as the industry

and market segment of the employer, as well as prior compliance history.[5]

6.6

The ATO also highlighted the component of the compliance program that

examines employers that are suspected not to have met their SG obligation.

Analysis of ATO held data enables the identification of employers who are

considered a high risk of not having met their SG obligations:

By comparing salary and wage data from individuals income tax

returns with SG payments as reported by funds in member contributions

statements, a general assessment can be made as to whether an employee may have

received the SG they were entitled to. This information is then aggregated to

an employer level. This assessment is by no means definitive, but can highlight

employers who have a high probability of underpaying SG. This strategy focuses

our audit resources upon those employers.

Reviews and audits undertaken under this strategy have

consistently produced stronger results in terms of adjustments raised per audit

than is achieve by our Employer Notification driven work.[6]

6.7

The ATO's approach to SG compliance activities can be generally

characterised as reactive, rather than proactive.[7]

6.8

The committee received evidence indicating that the ATO's heavy

reliance on EN to trigger compliance activities is problematic, as it places

the onus on affected employees to take action. This in turn presents challenges

to the timeliness of notifications and the likelihood of SG being recovered.

6.9

As the IGT outlined to the committee, even if affected employees are

aware of SG non-payment, they may not take prompt action:

The reason is that they are usually amongst the most

vulnerable in our society and may be too afraid of potential repercussions such

as loss of employment. This is evidenced by the fact that approximately 70 per

cent of employees only notify the ATO of non-payment of their SG after the

relevant employment has ended. The result is that, generally, there is a

significant time lag between the non-payment of SG and when the ATO is made

aware of it, by which time the offending employer may no longer be a going

concern and it may not be possible to recover any such amounts.[8]

6.10

The TCFUA submitted that the approach taken by the ATO is at odds with

the systematic non-compliance with SG and award superannuation obligations

evident in high-risk industries:

The system is premised on a range of questionable assumptions

including:

-

that it is appropriate, on a policy level, to impose the greatest

onus on employees for ensuring that superannuation contributions are paid by

employers (i.e. that employees should essentially bear the primary risk in

relation to non-payment of superannuation);

-

that all employees have a good understanding of what

superannuation is, including an employer's obligations [in regard] to payments

and choice of funds;

-

that all employees have the resources and capacity (including

proficient English language and written skills) to effectively monitor their

superannuation payments, and secondly, make a complaint to the ATO in their own

name;

-

that employees will pursue non-payment of superannuation (despite

the risk of threats to ongoing job and income security);

-

that non-compliance is confined to individual employees, rather

than being an entrenched systemic problem at a particular workplace.[9]

6.11

Dixon Advisory also provided evidence that highlighted the problematic

aspects of a compliance regime too reliant on employee notifications. The

submission argued that placing the onus on employees to initiate the recovery

action with the ATO could be too daunting an experience for some individuals,

particularly in a small-medium business scenario where the fear of

recrimination may be high. The submission also stated that during periods of

poor business conditions where there was a strong perceived risk of foreclosure

or job loss, employees may consciously make the decision not to lodge an EN,

figuring that they would be better off foregoing SG if it assisted their

employer to remain solvent and protected their own job.[10]

6.12

Dixon Advisory noted that this logic was detrimental to employees, as

it was difficult for an individual employee to assess the complex risks to

their financial situation when it was highly likely they did not possess enough

information to gauge the true operating position of their employer.[11]

6.13

As an attachment to her submission, Dr Tess Hardy provided the committee

with a 2014 article from the UNSW Law Journal, authored by herself and

Professor Helen Anderson, which centred on issues around the detection and

recovery of unremitted superannuation.[12]

6.14

The article examined 'the limitations inherent in the individual

complaint/risk based approach nexus' and identified the flaws in the assumption

underpinning the current SG compliance regime. In particular, the article

outlined the ways in which the reality of the situation differs from the

assumption that employees are in a position to detect unpaid SG and report it

to the ATO. These included that:

-

employees may be ignorant of their SG entitlements, the source of

the entitlement, or how to check that correct payments are being made;

-

employees may fear that questioning their employer will result in

their dismissal;

-

employees may be more concerned about the underpayment of wages

and other entitlements;

-

employees may be unaware that underpaid wages almost

automatically means underpaid SG; and

-

to an employee missing out on employment entitlements, the ATO

may not seem the logical place to lodge a complaint over unpaid SG.[13]

6.15

The article summarised the outcome of this situation:

Combined, these issues make it relevant to inquire whether

the current approach is adequate in protecting employees and whether any of the

detection and enforcement functions, which are increasingly placed on

employees, can and should be shared with key government agencies.[14]

6.16

In a similar vein, the IGT submission observed:

It is clear that the ATO heavily relies on employee

complaints to uncover non-compliance with SG. However, as stated earlier such

complaints are typically not made promptly and result in unpaid SG often not

being recoverable. Accordingly, it is crucial that the ATO considers other

proactive approaches in addressing SG risks at the earliest possible stage.[15]

6.17

The IGT noted that one option to bolster the proactive compliance

activities of the ATO would be to conduct more SG specific audits based on risks

identified by the ATO's risk assessment mechanism. As an alternative, the IGT

also suggested that random audits could be conducted (as outlined in the 2010

IGT report), although it noted that the ATO had previously rejected such an

option.[16]

6.18

The IGT provided detail on the random audit option:

Whilst carrying out random audits may expose some compliant

employers to unnecessary compliance costs, these costs and inconveniences may

be minimised by the manner in which the ATO conducts these audits... Furthermore,

in light of the earlier discussion on the economic impact of unpaid SG, such

costs and inconveniences should be weighed against the potential disadvantage

that the very same compliant employers face if their competitors do not pay SG

and remain undetected.[17]

6.19

On the topic of the costs to employers for random audits, the IGT noted

that one option that could be considered by the ATO is a level of remuneration

or compensation for employers if they were found to be compliant.[18]

6.20

The IGT also asserted that random audits may lead to better targeting of

non‑compliant employers in the long term:

Certain common characteristics of non-compliant employers may

be exposed and they could be used to improve the ATO's current risk assessment

tools. As the ATO's current risk assessment processes largely rely on reported

data, these audits may be the only way that the most non‑compliant

employers can be detected. Furthermore, conducting random audits would allow

the SG gap to be more accurately measured.[19]

ATO handling of employee

notifications and resource levels

6.21

The committee received evidence noting concerns with how the ATO

responded to employee notifications.

6.22

For example, the TCFUA voiced concerns over the ability for an employer

to enter into a payment plan with the ATO for unpaid SG, without the knowledge

or consent of the affected employee.[20]

6.23

The TCFUA stated:

Typically in TCFUA's experience, the particular employer

commences making payments under the ATO payment plan, but eventually falls into

significant arrears again, and simply enters into another payment plan. The

pattern is often repeated over years, such that the employee's superannuation

is never up to date. Addressing such compliance 'churning' is time and resource

intensive and rarely leads to final or full resolution.[21]

6.24

The TCFUA recommended that it be compulsory for the ATO to notify the

affected employee and gain consent before entering into a SG payment plan with

a non-compliant employer.[22]

6.25

The ATO informed the committee that it contacts the individual who

lodged the EN by letter or email at each stage of the investigation to provide

a progress update or outcome.[23]

6.26

Another concern raised was the amount of time it took for the ATO to

resolve SG cases, and the lack of information provided to employees about how

investigations into their unpaid SG monies were proceeding.

6.27

Cbus observed that many of its members felt as if the ATO was not an

effective player in resolving issues regarding SG arrears. In addition, its

submission noted:

Cbus' experience of the ATO SG compliance area has sometimes

been frustrated by poor communication, extensive time taken in recovery and a

lack of confidence in the willingness of the ATO to pursue arrears given their

policy and resourcing restrictions.[24]

6.28

Similarly, the TCFUA informed the committee that many of their members

were frustrated with the slow timeframes of ATO investigations of ENs. Ms

Vivienne Wiles, the National Industrial Officer for the TCFUA elaborated on

these concerns:

It [the ATO] is too slow in a number of respects. It is too

slow to transfer the money to the super fund when it is received. Its

communication with employees is also very poor. It is really common for

employees to not even know that the ATO have even recovered any money. The

reporting from the ATO back to the employee often takes many, many months and

sometimes years.[25]

6.29

Ms Wiles continued by providing a specific example of significant ATO

delays:

We had one case where a number of employees, members of ours,

made complaints to the ATO and they literally heard nothing for three years,

and then they received a letter telling them that the company was insolvent and

had gone into liquidation and the ATO could do nothing further for them. It was

a really significant period... They are really left in the dark, which is ironic

because it is their money ultimately.[26]

6.30

As mentioned in chapter 2, according to the ATO, it aims to commence 99

per cent of ENs within 28 days of receipt, and where they proceed to audit,

complete 50 per cent of compliance cases within four months (this

benchmark is currently under review) and 90 per cent of compliance cases within

12 months. The ATO submission pointed out that since 2013, the benchmarks for

all three service standards has been met.[27]

Table

6.1—Employee Notification Service Standards[28]

| EN Service Standard |

Standard |

Benchmark |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

| Commenced

within 28 days of EN receipt |

28 days |

99% |

99.10% |

99.40% |

99.50% |

99% |

| Closed within 4 months |

4 months |

50% |

50.82% |

70.70% |

73.50% |

76% |

| Closed within

12 months |

12 months |

90% |

99.70% |

99.80% |

99.90% |

100% |

6.31

Although recognising the work done by the ATO to improve its complaint

response outcomes, JobWatch informed the committee that callers to its helpline

largely perceived the ATO's follow-up action as inadequate, and were

consistently frustrated with a perceived lack of ATO activity in investigating

complaints.[29]

6.32

JobWatch also emphasised that individuals who had lodged ENs often

reported feeling unhappy with their interactions with the ATO:

Anecdotally, many of our callers have complained about

feeling as if they had not been listened to thoroughly by the relevant

authorities, perceiving responses by the ATO as largely scripted and robotic.[30]

6.33

While recognising that providing individual updates is a time consuming,

resource intensive process, JobWatch recommended that, as much as possible, the

ATO take steps to personally explain the process of debt enforcement to

complainants:

The time taken to properly explain the complexities and

difficulties based on a personalised assessment of a complainant's situation

will go some way to ensure that, at the very least, the complainant feels

listened to.[31]

6.34

In regard to ATO resource levels, the Community and Public Sector Union

(CPSU) submitted that its members had observed that the ability of the ATO to

effectively undertake compliance activities (both in terms of the

identification and recovery of unpaid SG) was limited due to the decline of

ongoing staffing levels in recent years.[32]

6.35

The CPSU submission further sets out the limitations of the ATO's

complaints process:

Feedback from CPSU members is that due to prioritisation of

resources within the ATO, if an employee notifies that there has been a

non-payment of SG, an audit of all the SG payments by that employer is not

completed until a pattern of non-payment has been established. This forces the

burden of proof onto the employees of the business to establish a pattern of

behaviour, rather than a problem being identified by the compliance area within

the ATO.[33]

6.36

On the matter of resource levels, the ATO informed the committee that

the majority of resources for SG activities sit within the Superannuation

Business Line, with support services provided by client accounts services, law

design and practice, and customer service and solutions. The ATO stated that

the fulltime equivalent (FTE) number and proportion of staff working on SG

within the Superannuation Business Line remained at a similar level in 2016-17

as it had in 2015-16. The Superannuation Business Line currently has

approximately 350 FTE employed in active compliance, and of the work undertaken

by the active compliance staff, 170 FTE are involved in SG.[34]

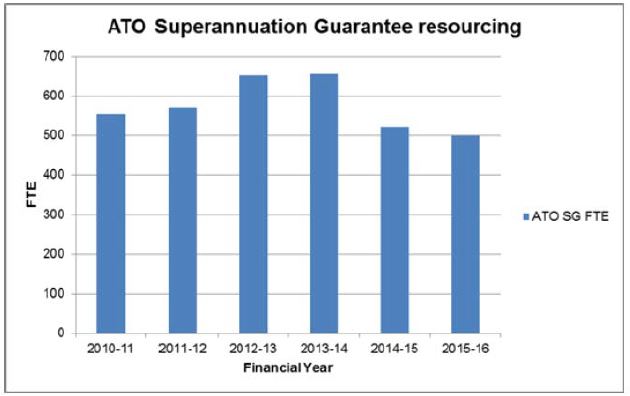

6.37

A graph of ATO SG resourcing indicated, however, that the FTE levels for

SG resourcing had dropped from a peak of well over 600 FTE in 2012-13 and 2013‑14,

to approximately 500 FTE in 2015-16.[35]

Figure 6.1—ATO Superannuation Guarantee resourcing, 2010-11

to 2015-16[36]

6.38

The Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) recommended

that the ATO be provided with additional funding to conduct an increased number

of SG specific audits of high-risk businesses.[37]

Committee view

6.39

The committee understands the concerns raised by submitters about the

challenges and limitations inherent in the ATO's current SG compliance

approach. In particular, the committee recognises that delays in the

investigations of employee notifications, as well as a lack of information on

the progress of an investigation, can cause significant frustration to

individuals awaiting an outcome on their unpaid SG complaint.

Recommendation 10

6.40

The committee recommends that the ATO continue to improve its

communication process with individuals to keep them promptly and meaningfully

informed of the progress of their employee notification.

6.41

Additionally, the committee is very concerned by evidence indicating

that the ATO is able to enter into payment plans with non-compliant employers

without informing the employee in question, whose money is being recovered.

Recommendation 11

6.42

The committee recommends that before entering into a payment plan to

recover SG from a non-compliant employer, the ATO be required to notify the affected

employee and gain their consent to the course of action.

6.43

The committee has serious reservations about the ATO's reactive approach

to SG compliance. The committee sees benefits in the ATO rebalancing its current

approach to SG compliance by increasing its focus on more proactive methods.

The committee urges the ATO to continue to move away from the current reliance

on employee notifications to trigger compliance activities.

Recommendation 12

6.44

The committee recommends the ATO give consideration to more proactive SG

initiatives, such as the options put forward by the Inspector‑General of

Taxation to incorporate random audits into its SG compliance activities.

6.45

The committee is aware that taking a more proactive approach, or

providing more detailed updates to complainants will necessarily require

further ATO resources. The committee notes that ATO SG resourcing levels in

terms of FTE numbers appear to have been reduced by a significant amount since

2012-13.

Recommendation 13

6.46

The committee recommends that the government review ATO resource levels

to ensure that the agency is well-equipped to undertake effective and

comprehensive compliance activities to combat SG non-payment.

The role of third parties in detecting and recovering unpaid SG

6.47

Some superannuation funds choose to take an active role in enforcing the

payment of their members' SG.[38]

For example, as mentioned in chapter 2, Industry Fund Services (IFS) provides a

range of services to not-for-profit superannuation funds. IFS stated that its

unpaid superannuation division, which specialises in the recovery of SG

(including arrears collection, enforcement and participation in insolvency

proceedings), acts on behalf of nine superannuation funds.[39]

6.48

IFS noted that a fund may appoint IFS as their agent at any point in the

SG collection process and outlined:

Some client funds utilise all of IFS's services while others

undertake arrears collection in-house (or at their outsourced administrator)

and rely on IFS for legal enforcement and/or insolvency proceedings only. IFS

has five funds representing more than 5.1 million accounts that utilise the

full suite of unpaid superannuation services.[40]

6.49

ISA informed the committee that in the absence of an award or another

kind of industrial agreement requiring the payment of a specific superannuation

amount, the SGA Act may be the only legal instrument imposing a specific legal

obligation on an employer to pay contributions. As such, the enforcement of the

SGA Act relies upon the potential imposition of an SG charge by the ATO. In

these instances, an affected employee or superannuation fund seeking to act on

their behalf are unable to take any action themselves and must instead rely on

the ATO.[41]

6.50

ISA noted that in an attempt to bridge this coverage gap, some

superannuation funds have developed deeds of agreement with contributing

employers in nominated workplace default fund agreements that explicitly

provide superannuation funds with the legal standing to act on behalf of their

members. Such agreements provide a record of a formal relationship confirming

that an employer has nominated a default fund and set out the employer

obligations to superannuation fund members.[42]

6.51

ISA explained the difficulties that arise without these default fund

agreements:

When no formal relationship exists between a fund and an

employer, funds have no standing to act on behalf of a member to recover

arrears or enforce debt. Employees who are exercising 'choice of fund' are not

usually covered by these agreements.

Noting the duty of superannuation fund trustees to recover

debts (but the lack of standing that some funds may have due to an absence of

an industrial award, enterprise agreement or an explicit default fund

agreement), allowing employees – or funds acting on their behalf to apply to

the ATO to give standing to recover arrears and pursue a debt would allow funds

to fulfil this duty.[43]

6.52

ISA recommended that in order to remedy gaps in the standing of

employees, or those acting on their behalf, to recover unpaid SG from an

employer, consideration should be given to amending the SGA Act to allow an

individual or agent (such as a superannuation fund or a service provider to the

fund) to recover SG shortfalls on application to the ATO. ISA asserted that

this could be achieved in a number of ways, including by permitting the ATO to

delegate an agent (e.g. the superannuation fund or a service provider to them)

to recover unpaid SG on application.[44]

6.53

When asked by the committee whether there was a place for superannuation

funds to recover unpaid SG, Mr Mark Korda, a partner at KordaMentha observed:

Obviously, they are incentivised to do that. They want to

look after their members first, but also the more you have the funds under

management the more you can defray your costs – the expense ratio.[45]

6.54

The TCFUA informed the committee that unions are unable to make

complaints to the ATO on behalf of individual employees or groups of employees,

and noted that it is a complicated process for employee representatives to

obtain information on behalf of the individuals they represent. The TCFUA also

indicated that while third parties can provide information to the ATO regarding

circumstances of SG non-payment, the ATO does not consider these tip-offs to be

formal complaints (i.e. employee notifications). The TCFUA submitted that this

represented a significant barrier to unions effectively assisting workers in

relation to SG non-payment and recommended that union representatives are acknowledged

as legitimate representatives of affected workers.[46]

6.55

JobWatch told the committee that many of its callers are frustrated to

learn that as employees they lacked the standing to sue their employer for

unpaid SG if their entitlements come from the SG legislation and not from a

common law contract, modern award, or registered agreement. As a result,

employees cannot take private legal action and must instead rely on the ATO to

enforce the SG legislation on their behalf.[47]

6.56

JobWatch recommended that there be a legislated option for employees to

take private legal action against their employers for unpaid SG, and noted that

this could be done by amending the National Employment Standards contained in the

Fair Work Act to include an entitlement to SG. JobWatch stated that this

would allow employees to issue proceedings to recover unpaid SG, including by

way of the small claims procedure outlined in the Fair Work Act.[48]

6.57

The IGT noted that when examining whether the law should be changed to

provide employees better direct access to avenues of redress, consideration

should be given to whether such a legislative change would be an effective

solution when often employees may not have the resources or funds to pursue the

matter themselves.[49]

Committee view

6.58

The committee is of the view that third parties could play an important

role in detecting and recovering unpaid SG. The committee believes that the

current arrangement, whereby an individual cannot take private legal action

against their employer if their SG entitlements stem purely from the SGA Act,

is inadequate.

Recommendation 14

6.59

The committee recommends that the government consider a legislated

option for employees, or third parties acting on their behalf, such as unions

or superannuation funds, to take private legal action in the relevant courts against

their employers for unpaid SG.

Default fund criteria

6.60

Related to issues surrounding the role of third parties in recovering

unpaid SG, the committee received evidence from Cbus recommending that

superannuation funds seeking default status in industry awards be required to

have a rigorous arrears collection process in place. Cbus noted that the

current default fund criteria in the Fair Work Act does not include the issue

of SG compliance, and stressed that only funds with stringent processes in place

for dealing with unpaid SG should be considered when assessing funds for

default fund status.[50]

Committee view

6.61

The committee considers it pertinent that any superannuation fund

seeking default status in an industry award be required to have a proper arrears

collection process in place. This would ensure that a fund member who

encounters unpaid SG is able to access appropriate assistance in recovering the

money.

Recommendation 15

6.62

The committee recommends that superannuation funds seeking default

status in industry awards be required to have a rigorous arrears collection

process in place.

Effectiveness of the SG Charge

6.63

As outlined in chapter 2, if an employer does not pay the correct SG

contribution to an employee's nominated fund by the quarterly payment due date,

they may be liable for the SG Charge (SGC), payable to ATO..[51]

6.64

An employer subject to the SGC must lodge an SGC Statement with the ATO,

calculate the amount payable, and pay the charge by the due date for the

relevant quarter. The ATO then forwards the shortfall and nominal interest

component to the employee's superannuation fund.[52]

6.65

Evidence received by the committee indicated that the ATO is reliant

upon employers self-reporting to trigger awareness of non-compliance cases. As

the ATO submission stated:

The lodgement of an SGC Statement informs the ATO that an

employee has not met their SG obligations. It allows the ATO to follow-up and

ensure compliance and payment.

If an employer does not lodge an SGC statement, the ATO has

powers to raise the SG Charge assessment and the employer can be liable for a

penalty of up to 200 per cent of the charge amount.[53]

6.66

It would appear that under this arrangement the ATO only becomes aware

that an employer has not lodged a SGC Statement when an employee lodges an EN,

or if the non-compliance is picked up during ATO initiated compliance

activities (e.g. through SG proactive audits or the analysis of data to

identify SG high risk employers).[54]

6.67

Given that only 30 per cent of the cases of SG non-compliance the ATO

looks into are ATO initiated, it could be reasonably concluded that an employer

who does not lodge an SGC Statement does not face a high risk of being detected

by the ATO.

6.68

One of the three components of the SGC is a nominal interest amount (currently

set at 10 per cent from the beginning of the period). This component is

designed to compensate an employee for lost investment returns on the unpaid SG

amount. However, ISA asserted that as non-compliant employers obtained a cash

flow benefit from not paying SG on time (for example interest savings on

business loans, credit cards or overdrafts), those interest rate benefits may

in effect offset the nominal 10 per cent interest charge. This in turn reduces

the impact of the SGC penalty on an employer.[55]

6.69

ISA also argued that the SGC penalty regime overall does not provide a

strong enough disincentive to non-compliant employers:

On balance, the existing penalty regime for employers who are

failing to meet their SG obligations is not effective. The risk of detection,

by either proactive audit or employee complaint, is very low. The SGC penalty

regime appears to have been designed merely to provide a modest disincentive

for making late payments. It is not a deterrent to employers wilfully ignoring

the SG liability.[56]

Committee view

6.70

The committee is concerned that the SGC regime relies heavily on non‑compliant

employers self-reporting. While the committee acknowledges that many employers

seek to do the right thing and do lodge SGC statements, there are also some unscrupulous

employers who attempt to circumvent the system.

6.71

The committee is mindful of the view put forward by the IGT that when

assessing the effectiveness of the SGC, there is a need to strike a balance

between the deterrent aspects of the charge, as well as appropriate

consideration of the employer's circumstances.[57]

However, the committee is of the opinion that the current SGC does not amount

to a strong enough deterrent for employers who purposefully seek to evade their

SG obligations. The committee considers there is a need for stronger penalties

for deliberate and repeated non-compliance as such behaviour severely

disadvantages individual workers, damages the competitiveness of compliant

employers, and ultimately undermines the system as a whole.

Recommendation 16

6.72

The committee recommends that the government review the SGC regime and

its management by the ATO to ascertain whether it is adequate, with a view to

increasing penalties for deliberate and repeated acts of non-compliance by

employers.

ATO and FWO compliance responsibilities

6.73

The committee received evidence regarding the division of

responsibilities for superannuation entitlements between the ATO and the Fair

Work Ombudsman (FWO) and the impact of this division on SG compliance efforts.

6.74

The Department of Employment outlined the role of the FWO in relation to

superannuation entitlements as follows:

Under the Fair Work Act 2009 (FW Act), the Fair Work

Ombudsman (FWO) has limited direct functions relating to superannuation

entitlements, generally confined to providing advice about and enforcing

compliance with modern awards and enterprise agreements requiring employers to

make superannuation contributions, and record keeping and payslip requirements

relating to superannuation contributions.

The FWO responds to complaints of underpayment made by

employees by gathering payment information from both the employee and the

employer. FWO does not have statutory access to payment information from

employers or superannuation funds in the same way as the ATO. Therefore [the]

FWO is not able to proactively monitor SG and in the majority of circumstance,

will forward on complaints regarding SG contribution to the ATO for action...

The FWO has powers to seek court orders for the underpayment

or non‑payment of wages, including court orders for a contravention of a

modern award term or enterprise agreement. If a court finds that an employer

has breached its obligations to pay wages or superannuation, the employer may

be liable to a pecuniary penalty, in addition to repayment of unpaid wages and

unpaid superannuation guarantee contributions.[58]

6.75

Mr Michael Campbell, the Deputy Fair Work Ombudsman (Operations),

clarified that:

Our power to enforce a superannuation payment would only

arise through a modern award and it would depend on how that clause is drafted

to determine what our enforcement possibilities would be. If it is specific and

it requires a percentage payment then we can enforce that as part of our

regular work.[59]

6.76

Dr Tess Hardy provided the committee with an example illustrating that

the FWO does have the ability to pursue superannuation entitlements in some

situations:

Certainly, although the Fair Work Ombudsman has a practice of

dealing with underpayments of minimum wages and referring the superannuation

shortfall issues to the ATO, there are a number of cases where it has pursued

superannuation entitlements as part of a broader proceeding in relation to

underpayment of wages. It is certainly within their ambit to pursue

superannuation entitlements where, of course, they arise within their

jurisdiction, which is under a modern award, under an enterprise agreement or

as a safety net contractual entitlement. They have done so.[60]

6.77

Dr Hardy went on to give a specific example of such a situation:

There was a recent case in the Federal Court of the Fair Work

Ombudsman and Grouped Property services, which involved the underpayment of

wages, various other entitlements and superannuation contributions. There were

48 award-covered employees and three award-free employees. For the 48

award-covered employees the Fair Work Ombudsman was able to seek compensation

for lost superannuation and lost interest. The three award-free employees would

have to rely on the ATO to take action on their behalf. That is kind of an

illustration of the way in which the award coverage has implications for the

Fair Work Ombudsman's jurisdiction and recovery of those underpayments through

the courts.[61]

6.78

The FWO informed the committee that of the formal requests for

assistance finalised by the FWO in 2015-16, approximately 5 per cent (1242

requests) involved a reference to superannuation.[62]

6.79

Mr Andrew Fogarty, Executive Director of Policy, Media and

Communications at the FWO clarified that:

...we really structure ourselves at the moment so that, at the

front end, if someone comes to our contact centre, for instance, or calls us,

we are, right at the beginning, referring them to the ATO if their question is

about superannuation or taxation.[63]

6.80

When the committee sought further information on when the FWO does act

to enforce SG, Mr Campbell outlined that although the jurisdiction of the FWO

was enlivened when an award provided for a specific percentage SG payment and

it was an award entitlement, in practice, the FWO method of operation was to

refer SG to the ATO. As Mr Campbell noted 'they [ATO] have a broader coverage

and greater powers to conduct this work and, ultimately, it is more effective

than our seeking to do it.'[64]

6.81

Mr Campbell went on to provide the committee with further detail around

the approach of the FWO to superannuation non-payment:

In simple terms, the work we focus on is that which is

clearly within our jurisdiction. The ATO has a broader jurisdiction than ours.

It reaches more employees and employers and it has a better toolkit and set of

powers to seek out and recover unpaid superannuation. So we refer it to them

and we think that is an appropriate approach. It is not that we do not

prioritise or think that it is important, but the mechanism that we have in

place works. That is how we treat that work.[65]

6.82

When questioning other witnesses on what might be behind the apparent

reluctance of the FWO to engage in the superannuation compliance issues, the

committee received the following evidence:

Chair: In your view, what explains the Fair Work

Ombudsman's reluctance to engage in this area? Are there some administrative

difficulties for them which make it easier for them to refer to the ATO or is

it simply that the ATO is recognised within government as being the relevant

enforcement agency? Is there something other than just an informal division of responsibilities?

Dr Hardy: I certainly think there is the perception

that the ATO is the principal regulator in this space. The other obvious issue

would be one of resources. The more time they spend on enforcing superannuation

entitlements, the less resources they have for addressing other issues that

they might perceive as more squarely within their jurisdiction or not within

someone else's jurisdiction.[66]

6.83

The memorandum of understanding between the ATO and the FWO as it relates

to information sharing between the two agencies is covered in chapter 7.

Committee view

6.84

The committee is of the view that the FWO should be more active in the

SG compliance space. Rather than simply referring SG matters to the ATO, the

committee believes that the FWO should actively assist employees in resolving

unpaid SG matters where appropriate under their jurisdiction.

Recommendation 17

6.85

The committee recommends that the ATO review all current compliance and

recovery activities related to unpaid SG to determine which ones should remain

with the ATO, and which ones could be transferred to, or shared with, the Fair

Work Ombudsman. As a starting point, the committee recommends that the Fair

Work Ombudsman begin to receive and act on SG non-payment complaints where

appropriate, rather than simply referring the affected employees to the ATO.

Recommendation 18

6.86

The committee recommends that the government consider increasing the

resource levels of the Fair Work Ombudsman to ensure it is properly equipped to

carry out any additional SG compliance or recovery activities it may acquire

from the ATO.

Unpaid SG in the event of insolvency

6.87

Employer insolvency poses a serious challenge to the payment of SG. In

addition to the loss of wages, annual leave and other redundancy entitlements,

the loss of unpaid SG is of great concern to affected employees, particularly

in a situation where SG entitlements have not been remitted for a significant

period of time, if at all.

6.88

As Professor Helen Anderson and Dr Tess Hardy noted in an academic

article in the UNSW Law Journal submitted by Dr Hardy part of her submission:

Corporate insolvency exacerbates the recovery of unpaid

employment entitlements, including any unremitted superannuation contributions,

because the main target of enforcement action – the company– is likely to have

insufficient assets to meet the claim.[67]

6.89

JobWatch stated that many of its callers reported being dissatisfied

with their inability to recover unpaid SG when their employer had gone into

liquidation or been declared bankrupt. JobWatch also stated that in some

situations, although an employee had lodged an EN with the ATO before their

employer's bankruptcy or liquidation, by the time the ATO conducted an

investigation the insolvency process had already begun. JobWatch noted 'the

lengthy and secretive investigation process for recovery through the ATO is

inadequate in these situations as rapid resolution is essential to prevent

employee entitlements from being subjugated by other creditors'.[68]

6.90

According to the ATO's submission, 36 per cent of EN cases were raised

against employers displaying an insolvency indicator on ATO systems, which made

debt collection unlikely. This in turn meant that the ATO was generally unable

to collect any SG payment for affected employees.[69]

In addition, the ATO observed that due to the time lag in reporting the

non-payment of SG contributions, insolvency was a significant issue in the

recovery of SGC debt, with $113.2 million irrecoverable at law in 2015-16.[70]

Effectiveness of Director Penalty

Notices

6.91

The ATO informed the committee that administrative improvements to the

recovery of unpaid SG could potentially be achieved by improving the systems

that support the issuing of Director Penalty Notices (DPNs) . Since

2012, the Director Penalty regime (enacted through Division 269 of Schedule 1

of the Taxation Administration Act 1953) has been applicable to company

SGC liabilities. As a result, the ATO Commissioner is able to recover SGC

liabilities by pursuing a parallel liability imposed on the company directors

in the form of a penalty.[71]

6.92

For example, the ATO would issue a notice requiring a director to pay

any unpaid SG, and if the director did not comply with the notice by the due

date, the director becomes personally liable for the penalty amount until it is

paid in full.[72]

6.93

However, the effectiveness of this framework is limited in situations

involving an insolvent company. For example, if the ATO sends a DPN to the

director of an insolvent company, the director is able to escape personal

liability by simply liquidating the defaulting company within 21 days of

receiving the notice. This means that any unpaid SG amounts are not

recoverable.[73]

6.94

The ATO elaborated on this point:

...the liquidation or voluntary administration of the company

automatically extinguishes any director penalty which was not already the

subject of a Director Penalty Notice (s 269-25 of the TAA [Taxation

Administration Act 1953]) issued more than 21 days prior to the

commencement of the insolvency administration or where the associated SGC

liability was not reported for more than three months at the time that the

administration commenced. Given that the reporting date for SGC is two months

following the end of the quarter, it is often the case that the eventual

liquidation of the company extinguishes the director penalties related to the

past eight months of the company's unpaid superannuation obligations.[74]

6.95

Similarly, in an article in the University of New South Wales Law

Journal by Dr Tess Hardy and Professor Helen Anderson, the two academics

outlined their concerns with the adequacy of the DPN system:

Companies wishing to avoid these (and possible other)

liabilities can simply liquidate or enter voluntary administration before three

months has elapsed without reporting or paying their SGC liabilities. In such

circumstances, the directors will face no personal consequences, even if the

ATO later identifies the lack of superannuation payment. The business may then

be reborn through a 'phoenix' company and the behaviour continues.[75]

Committee view

6.96

The committee is concerned by the apparent deficiency of the current DPN

framework as it relates to unpaid SG by companies that become insolvent. The

committee is of the view that this unintentional loophole must be urgently

addressed in order to stop unscrupulous employers from engaging in fraudulent

phoenix activity and avoiding their superannuation obligations.

Recommendation 19

6.97

The committee recommends that the government investigate potential

legislative amendments to strengthen the ATO's current ability to recover SGC

liabilities through the Director Penalty Notice framework in order to stop

company directors undertaking fraudulent phoenix activity and avoiding their SG

obligations.

Impact of illegal phoenix

activities

6.98

Phoenix activity is generally based upon the failure or abandonment of

one company, only to have a second company 'rise from the ashes' of the first,

with the same controllers and business. Such activity is illegal when, in a

breach of directors' duties, the intention of the company's controllers is to

shed debts while continuing what is essentially the same business through the

new entity. The non-payment of taxes and employee entitlements, including SG,

is often the core objective of illegal phoenix activity.[76]

6.99

A February 2017 report by Professor Anderson and colleagues at the

Melbourne Law School entitled 'Phoenix Activity: Recommendations on Detection,

Disruption and Enforcement' recommended the use of director identification

numbers (DIN) for all company directors to allow ASIC and other regulators to

monitor and track repeat offenders engaging in illegal phoenix activity.[77]

6.100

It is currently possible to register an Australian company by simply

providing ASIC with the name, address and date of birth of each proposed

officeholder. ASIC does not ask for the prior corporate history of the proposed

directors, nor does it independently verify the information provided to it.

This is problematic as repeat offenders in illegal phoenix activity can attempt

to conceal their previous multiple directorships under the guise of a 'dummy

director' (for example, by providing the name of a relative or fictitious

character, deliberately misspelling their name, or listing an incorrect date of

birth.[78]

6.101

To combat this behaviour, Professor Anderson's report proposed the

following details for a DIN scheme:

The limitations of the existing company registration

requirements could be overcome through the relatively simple and cheap process

of requiring directors to establish their own identity via 100 points of

identity proof, which would accord with the well-accepted and uncontroversial

practice for opening bank accounts and obtaining passports. Directors would

then be allocated a unique DIN, which would enable tracking of company

directors who have been involved in multiple corporate failures and who may be

likely to engage in armful phoenix activity.[79]

6.102

In her inquiry submission Professor Anderson also suggested that a DIN

scheme could assist credit reporting agencies in acting as market-based regulators.

If given information about unremitted SG and those directors responsible for it

(identified through the DIN), credit reporting agencies could in effect make it

more difficult for unscrupulous directors to obtain finance for their future

companies.[80]

6.103

The Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association

(ARITA) informed the committee that it supported a DIN scheme as set out in the

research by Professor Anderson, noting that it is a policy they have strongly

advocated for to reduce instances of illegal phoenix activity.[81]

Committee view

6.104

The committee considers that a DIN initiative has merit as it would go

some way to preventing directors engaging in illegal phoenix activity and

repeatedly avoiding SG obligations with impunity. The committee also considers

that the potential for a DIN initiative to assist credit reporting agencies in

identifying individuals who engage in illegal phoenix activity is worth further

investigation.

Recommendation 20

6.105

The committee recommends that the government consider implementing a

Director Identification Number scheme to prevent individuals engaging in

illegal phoenix activity and repeatedly avoiding SG obligations.

Impact of trusts on unpaid SG

during liquidation

6.106

The committee received evidence indicating that the method in which an

employee is employed (i.e. via a company structure or via a trust) can impact

the priority of employee entitlements during the liquidation of a company. This

in turn impacts on the ability for employees to recover unpaid SG amounts.

6.107

ARITA informed the committee that in the event of the liquidation of a

company, employee entitlements (such as unpaid SG) are given priority over

ordinary trade creditors. ARITA observed, however, that recent court decisions[82]

have determined that if the business is traded and employed through a trust,

all creditors rank equally when it comes to the distribution of available

funds.[83]

Specifically, if a business is operated through a trust structure, it is

outside the operation of section 556 (relating to priority payments) of the Corporations

Act 2001 (Corporations Act).[84]

6.108

ARITA provided the committee with the following example to explain the

impact on the recovery of unpaid SG amounts of employees of an insolvent

company:

...if a butcher trades using a company structure, employee

entitlements owing to the apprentice would be paid in priority to the debts

owing to the butcher's meat supplier. If the same business was instead traded

through a trust structure, the apprentice and the meat supplier would rank

equally. Where there are insufficient funds available to pay all outstanding

amounts, this reduces the amount of outstanding entitlements that the employee

would receive, including any superannuation...[85]

6.109

In a submission in his private capacity, Mr Geoff Green, a chartered

accountant and former registered liquidator, argued that as the use of

discretionary trusts is widespread in commercial practice, many thousands of

employees could be impacted. Mr Green stated that if the level of protection

afforded to employee superannuation and other priorities is dependent on the

type of structure used by the employer, then in practical terms it was firstly

inequitable (because there is no business or commercial justification for such

a difference); and secondly impractical (because employees cannot be expected

to identify the type of structure by which they are employed, or to understand

the consequences of the structure).[86]

6.110

Mr Green suggested that a solution to this problem would be to amend the

Corporations Act so that section 556 priorities apply in all

liquidations. Mr Green noted that this would implement the recommendation set

out in paragraph 265 of the Australian Law Reform Commission's 1988 Harmer

report.[87]

Mr Green also observed that as an alternative to amending section 556 of the

Corporations Act, a new provision that operates to create priority for employee

entitlements and SG debts ahead of trust creditors (in the same way that

section 561 currently gives priority to employee entitlements and SG debts

ahead of circulating security interests) could be created. In addition, Mr

Green noted that any changes should be drafted to allow for the possibility

that corporate entities might be the trustee of more than one trust, or might

also employ staff in their own right.[88]

Committee view

6.111

The committee considers it inequitable that individuals employed in

businesses operating through a trust structure with unpaid SG are not

considered to have priority over ordinary creditors in the event of employer

insolvency.

Recommendation 21

6.112

The committee recommends that the government consider amending the

Corporations Act to ensure that the priorities in section 556 apply during all

liquidations, regardless of whether the business being liquidated was operated

through a trust structure.

Other issues relating to payment

and calculation of SG during liquidation

6.113

The committee received evidence on other issues relating to the payment

and calculation of SG during liquidation processes.

6.114

For example, ARITA highlighted the inconsistency in the calculation of

the nominal interest component of the SGC between the SGA Act and the

Corporations Act. ARITA stated that under the Corporations Act, creditors are

entitled to include interest up to the date of liquidation in their claim, if

the terms of their debt provide for interest to accrue. However, when the ATO

calculates the nominal interest of the SGC on unpaid super, the nominal

interest is calculated up to the date of lodgement of the SGC statement. This

date of lodgement is generally after the date of liquidation.[89]

6.115

ARITA argued that this inconsistency could potentially disadvantage

other creditors in the liquidation due to the priority status of the SGC

amount:

In our view, this is inappropriate, as creditors in the

liquidation should enjoy the same rights and privileges unless specifically

differentiated by the Corporations Act... In our view, all interest should be

treated equally and the right to interest should be calculated as at the date

of liquidation.[90]

6.116

ARITA also informed the committee that feedback from its members showed

there were often lengthy delays between when an SGC payment is made to the ATO

as part of an insolvency process, and when those funds are remitted to an

employee's superannuation fund. To solve this, ARITA suggested that power be

given to insolvency practitioners to pay dividends for unpaid SG directly to an

employee's superannuation fund (where details of the fund are known). Any

payments could then be reported to the ATO, and the associated administration

component of the SGC be paid directly to the ATO.[91]

Committee view

6.117

The committee is of the view that both these issues warrant further

investigation in order to ascertain whether any changes could be made to allow

employees to promptly receive their SG entitlements in the event that their

employer becomes insolvent.

Recommendation 22

6.118

The committee recommends that the government consider amending the SGA

Act so that nominal interest on SGC in the case of insolvencies apply up to the

date of liquidation, in alignment with other creditors as set out in the

Corporations Act.

Recommendation 23

6.119

The committee recommends that the government consider amending the SGA

Act to allow insolvency practitioners to pay outstanding SG contributions

directly to an employee's superannuation fund.

Fair Entitlements Guarantee scheme

6.120

The Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG) is a publicly funded safety net

scheme of last resort designed to protect accrued basic employment entitlements

administered by the Department of Employment under the Fair Entitlements

Guarantee Act 2012 (FEG Act). FEG commenced as a legislated scheme in

December 2012, replacing the previous administrative version of the scheme, the

General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS).

6.121

FEG allows employees who have lost their jobs due to the liquidation or

insolvency of their employer and who are unable to recover particular

entitlements, to apply to receive financial assistance, with all payments

subject to a capped weekly amount.[92]

6.122

Unpaid SG is specifically excluded from FEG. The five basic employment

entitlements covered under the scheme are as follows:

-

unpaid wages (capped to 13 weeks)

-

unpaid annual leave

-

unpaid long service leave

-

payment in lieu of notice (capped to five weeks)

-

redundancy pay (capped to four weeks per full year of service)[93]

6.123

The Department of Employment provided the committee with some background

on the policy design of FEG:

In policy design, FEG and its predecessor schemes were not

intended to be an all-encompassing form of insurance to compensate employees

for any and all unpaid amounts owed by their employer. The design of FEG

provides for protection of limited categories of 'employment entitlements'

aligned to those entitlements that an employer is obligated to provide in the

National Employment Standard under the Fair Work Act 2009.[94]

6.124

The Department of Employment also elaborated on why SG was not covered

under FEG:

Despite the earlier commencement of Australia's compulsory

employer superannuation regime, unpaid compulsory superannuation contributions

owed by an insolvent employer have never been included in the policy design of

FEG or its predecessor schemes. Superannuation has a different policy genesis

and intent than the employment entitlements covered under the FEG. Employer

superannuation contributions under the Superannuation Guarantee (SG) are not an

item paid directly to employees as they fall due, nor do they become payable directly

to an employee on redundancy. Rather, SG contributions are accumulated in a

superannuation fund and accessed at a later time on an employee's retirement

from the workforce.[95]

6.125

The Department of Employment also stated that the FEG scheme presents a

'moral hazard' as it potentially shifts the cost of employer accountability for

employee entitlements obligations to tax payers. The department noted that as

FEG has become more generous over time, the moral hazard risk that insolvent

employers rely on the scheme to meet employees entitlements has increased.[96]

6.126

Numerous submitters recommended that FEG be expanded to cover unpaid SG.

For example, Cbus, the ACTU and United Voice all recommended that consideration

be given to expanding FEG to include SG entitlements.[97]

6.127

ISA argued that even though an expansion of FEG to include SG would

create costs to government, these costs may be offset over time through a

decrease in the number of affected employees reliant on the age pension years

later. ISA also stated that including SG in FEG would create an incentive for

government to administer an effective SG compliance regime.[98]

6.128

JobWatch informed the committee that although superannuation and wage

entitlements have equal standing in insolvency legislation when it comes to prioritising

payments, if an employee is unable to access superannuation due to employer

insolvency, there is no other option for remuneration available to them.[99]

6.129

The Association of Super Funds Australia (ASFA) recommended that unpaid

SG entitlements be included in the unpaid employment entitlements covered by

FEG. ASFA stated that there was merit in reviewing the treatment of unpaid SG

entitlements in insolvency cases as, according to ASIC data, a substantial

number of insolvency cases involved unpaid SG entitlements.[100]

6.130

The Association of Financial Advisors (AFA) pointed out that unpaid SG

liability can be a cause of employers entering insolvency arrangements in the

first place, meaning employees could potentially miss out on substantial sums

of retirement funds rightfully owed to them. AFA suggested that the FEG scheme

be reviewed to consider the protection of SG entitlements in liquidation.[101]

6.131

The committee also received evidence from the IGT indicating that the

inquiry was not the first time that the expansion of the last resort employee

entitlement scheme has been canvassed. In the 2010 IGT Super Guarantee Charge

review, the IGT recommended an expansion to both GEERS and the Director Penalty

Notice (DPN) regime to cover unpaid SGC liabilities.[102]

6.132

The recommendation read as follows:

Recommendation 11

To better protect employees' SG entitlements and improve both

deterrence against SG non-compliance and provide greater transparency of the

cost of SG non-compliance on future age pension outlays, the Government consider:

-

Expanding the director penalty regime to apply to unpaid SGC

liabilities of the company; and

-

Expanding GEERS to cover unpaid SGC liabilities where a company

has been placed into liquidation and the ATO has not been able to recover

against the directors personally.[103]

6.133

Although the suggestion to expand GEERS was not actioned, the DPN regime

was expanded to include unpaid SGC liabilities in June 2012. As a result of

this, if a company fails while owing SG to employees, directors of the company

may become liable for any unpaid superannuation entitlements. The policy intent

behind the expansion was to establish a deterrent against non-compliance and

improve the ATO's ability to recover unpaid SG even after a company had been

declared insolvent.[104]

6.134

However, according to the IGT submission, this expansion was supposed to

be complemented by an expansion of the last resort employee entitlement scheme:

The IGT explained in his 2010 SGC Review that the expansion

of both DPNs and GEERS to cover unpaid SGC complementary. Where a company has

not met their SG obligations, the ATO should have the ability to recover unpaid

SGC amounts from the directors of companies personally. Only when the ATO has

not been able to recover unpaid SGC liabilities from the company and the directors

should GEERS, now FEG, cover unpaid SG.[105]

6.135

The Department of Employment (the department) argued that FEG not be

expanded, asserting that notwithstanding the availability of FEG as a last

resort safety net, the government had clearly stated that it is the

responsibility of an employer to meet its employee entitlement obligations. The

department also stated that taxpayers should not have to provide a

comprehensive and unlimited source of funding to compensate employees where the

employer fails to make adequate provision for the accrued entitlements of its

workers.[106]

6.136

The department asserted that including unpaid SG contributions in FEG

would:

-

significantly increase the cost of the scheme;

-

exacerbate the existing moral hazard inherent in the scheme; and

-

create unnecessary policy and administrative complexity.[107]

6.137

In particular the department argued that expanding FEG to include unpaid

SG would result in an increase of around 47 per cent in the number of claims to

the scheme. This would in turn result in additional administered expense for

the government, which the department estimated to be $801 million over the

forward estimates. The department also claimed that changes to business systems

would be needed to administer assessment and payment of the superannuation

component of claims, at a cost of an extra $39 million to departmental expenses

over the forward estimates.[108]

6.138

The following table was provided by the department to illustrate the

additional expenditure:

Table 6.2—Summary of additional expenditure flowing from an

expansion of FEG[109]

|

Item

|

2017-18

|

2018-19

|

2019-20

|

2020-21

|

Total

|

|

Administered expense (million)

|

$180.6

|

$193.2

|

$206.6

|

$220.9

|

$801.2

|

|

Departmental expense (million)

|

$5.41

|

$8.49

|

$8.47

|

$8.52

|

$39.34

|

6.139

The department also flagged that expanding FEG would require legislative

amendment to the FEG Act, as well as possibly the SGA Act and other

legislation:

It can be anticipated that significant complexity will be

encountered in effectively straddling the overlap between FEG and the ATO in

managing non-payment of SG contributions. The ATO already has regulatory and

compliance responsibility for SG contributions. Including SG contributions in

FEG will work at cross purposes to the existing compliance regime including the

SG Charge arrangements, possibly resulting in a higher level of non-compliance.[110]

6.140

Rather than expanding FEG, the department recommended that the committee

consider measures to strengthen the powers available to the ATO to manage SG

compliance. The department stated that expanding FEG to include SG would not

likely achieve the desired result of improving compliance in employers meeting

their ongoing SG obligations.[111]

Committee view

6.141

The committee is mindful of the concerns put forward by the Department

of Employment in regard to the additional expenditure that would be required to

expand the FEG scheme to cover unpaid SG entitlements. The committee is aware

that any change to FEG would need to be carefully considered and undertaken

only when there is scope in the federal budget to adequately fund it.

6.142

However, as mentioned earlier in this report, the committee is strongly

of the view that SG forms an integral part of an employee's remuneration and is

akin to deferred wages. As such, the committee does not agree with the

Department of Employment's argument that the different policy genesis of

superannuation, as well as the fact that SG is not paid directly to employees

as it falls due, nor payable directly to employees on redundancy, are valid

reasons for excluding SG from the FEG scheme. The fact the SG contributions are

deferred wages does not diminish their importance. The FEG scheme has always

covered unpaid wages, and therefore it is logical that SG, as deferred wages,

should also be covered.

6.143

Additionally, the committee notes that although including SG in the FEG

scheme would increase current costs to government, the likelihood is that

government expenditure would instead be decreased in later years due to a

reduced reliance on the age pension from those affected employees. The

committee is also of the view that if the ATO undertakes more proactive work to

prevent SG non-payment as recommended, this will partially offset the increased

costs to the FEG scheme should SG be included.

Recommendation 24

6.144

The committee recommends that the relevant government agencies undertake

further research into the fiscal and legislative impacts of an expansion of the

current Fair Entitlements Guarantee scheme to cover unpaid SG entitlements.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page