Chapter 17

Land tenure and access to finance

17.1

More than 80 per cent of the total land area in the Pacific region is

under a complex and diverse system of customary land tenure.[1]

Access to this land is an important factor in economic development in Pacific island

countries and a major consideration for investors. In this chapter, the

committee considers land ownership and its implication for economic development

and investment. It also considers access to finance.

Land ownership—obstacles to development

17.2

A number of witnesses suggested that the complex and sensitive nature of

land tenure arrangements in the region was an obstacle to economic development

and argued that to achieve economic reform, changes were needed.[2]

They identified buying and selling customary land and establishing legal title

as the main difficulties.[3]

For example, Mr Garry Tunstall, ANZ, informed the committee that it would be

preferable to have a land title system that worked where land could be bought

and sold. He explained

...if you want to borrow money and undertake investment by

borrowing money then a financial institution is unlikely to lend that money on

custom land.[4]

17.3

The Centre for Independent Studies noted that land surveys, registration

and enforcement of private property rights need to be established in the

Pacific.[5]

Ms Hayward-Jones suggested that some kind of consensus on how land is to

be used, who owns the product being sold and what can be built on the land is

important.[6]

She agreed with the view that the issue of land tenure is critical for private

sector development and needs to be resolved. She noted that if agriculture is

to be encouraged then land tenure, particularly in Melanesia, 'needs to be

sorted out'.[7]

17.4

The issue of land tenure affects many sectors of the economy. Mr Frank Yourn,

Australia Papua New Guinea Business Council, informed the committee that

sometimes land tenure issues produce difficulties with the development of

national infrastructure, such as telecommunications, roads and bridges. He

noted that a telecommunications company would have to engage in complicated

negotiations with landowners to secure a site for a transmission tower.[8]

A number of witnesses referred to land ownership, particularly disputes over

land tenure, as possible impediments to mining activity.[9]

17.5

Despite these identified problems, a number of witnesses informed the

committee that Pacific island countries have arrangements that attempt to

address the issue of land tenure. Larger projects, including agricultural ones,

are often in a better position to look after their own interests. For instance,

New Britain Palm Oil has a successful palm oil plantation in West New Britain

with 7,000 employees and also 7,000 private out growers. The larger plantation

is on leasehold land which allows the operator to plant palm oil. On the other

hand, the out growers, who work on land they own under custom rights, sell palm

nuts to the plantation for which they receive income.[10]

17.6

ANZ cited the mining industry as a sector that 'has demonstrated that

sensitive land ownership issues can be managed'. Furthermore, it noted that the

sector's approach to handling land ownership issues could be replicated across

other parts of the economy.[11]

For example, Mr Graham, Esso, explained that his company in PNG does not

necessarily own the land but acquires access to it. This means that for the

pipeline route, the company does not purchase a strip of land but has access to

that land. The LNG plant itself, however, is different. He maintained that 'if

you are going to spend $6 billion on a plot of land, you want certainty about

title and access to it'.[12]

17.7

Mr Clarke also referred to land ownership arrangements under the Oil and

Gas Act in PNG which enable a developer to secure a title from the state

through a mining or a prospecting lease of some sort. Nonetheless, he pointed

out that much preparatory work is required before a title is granted, including

holding a forum, producing a detailed social map and determining customary boundaries.

While he was of the view that some good models of arrangements with customary

landowners were working under the legislation in PNG, he noted failings in the

bureaucracy.[13]

He explained that because of a lack of funding and of execution, the framework was

'just not working'.[14]

17.8

Fiji has also established a legislative framework for managing access by

foreign investors to traditional owned land. The Australia Fiji Business

Council noted:

Fiji has done better than most countries through the

establishment of its Native Land Trust Board which manages the relationship

between landowners and tenants, and generally provides an effective mechanism

to enable land to be utilised for economic purposes of benefit to both the

landowner and the land user.[15]

17.9

Under the framework, investors apply to the Native Lands Trust Board

which acts like an agency for the landowners and takes a commission. Mr Yourn

indicated, however, that:

It is a hefty commission and they are not always as efficient

as they might be, but at least there is a framework and a structure there for

managing access to land. You still have to have a relationship with the

landowners and you need to nurture that relationship and keep it going for the

whole life of whatever it is your business is on that land...[16]

17.10

Mr Anderson, President of the Council, informed the committee of resorts

that have been built and operate in Fiji and where, in many cases, landowners have

become the recipients of the goodwill of that hotel. In this regard, both Mr

Clarke and Mr Yourn suggested that land ownership in Pacific island countries

is generally an issue to be managed and not to prevent business.[17]

Mr Clarke said:

The issue is also making sure that you have got, and you can

work with, the customary owners. If you cannot get on with the customary owners

then a government title is not going to fix it.[18]

17.11

Despite the various arrangements in place to deal with land ownership

difficulties, some witnesses contended that land tenure in Pacific island

countries is still a problem and remains a contentious matter. Some argued that

it is not going to change. A recent AusAID publication noted that governments

in the region have 'tended to avoid interfering with customary tenure systems,

in terms of how they allocate rights, manage the land and keep records'.[19]

In stronger terms, Professor Moore told the committee that, at the moment, the

problem was 'intractable' and would be so for 'a generation or more'.[20]

17.12

Ms Hayward-Jones was of the view that the issue of land tenure was

critical. She indicated that there had been calls in a number of countries in

the Pacific for help on land ownership matters. In her opinion, this was an

area where external assistance might help because Pacific island countries feel

they cannot reform it themselves due to the indigenous politics around it.[21]

17.13

A number of witnesses, including the Australia Pacific Islands Business

Council and the Australia Fiji Business Council, suggested it was important for

individual Pacific island countries to own the solution and for it not to be

imposed externally.[22]

Dr Patricia Ranald, Australian Fair Trade and Investment Network, made a

similar observation. While recognising the importance of land tenure reform,

she stated that it should 'take place in each country according to the needs of

that country'—it should not be a one-size-fits-all process and should be

developed in consultation with the people involved.[23]

The Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Tonga underlined this point. He noted that

land tenure 'is one of the most delicate, difficult subjects in all Pacific

island countries':

Given the vast diversity of land tenure systems throughout

the region, it is definitely...one of a national, local, domestic character, and

one best dealt with by each country within its own borders and within its own

culture and traditions.[24]

17.14

The capacity of customary landowners to engage in land tenure

arrangements is also an important consideration. In its publication, Making

Land Work, AusAID referred to customary land practices in Vanuatu. It noted

that foreign investors 'are making deals with landowners that are very much in

the investors' favour'. It found that 'landowners are discovering that the

terms and conditions they agreed to are inadequate, or that they were not fully

informed about the implications of these terms and conditions'.[25]

AID/WATCH also referred to the residential and commercial developments in

Vanuatu that 'rarely benefit local people, preventing them access to

traditional lands and at times result in difficulties securing back their land

when lease terms have expired'. In its assessment, while the new land laws

implemented by the government in Vanuatu were able to contribute to the cash

economy, they have 'gradually marginalised the local indigenous population'.[26]

On this matter, the Prime Minister of Vanuatu recently voiced his concern about

his people being taken advantage of in making such arrangements.[27]

17.15

The committee has mentioned in a number of different contexts the lack

of capacity in Pacific island countries to negotiate agreements with better-resourced

countries. In some cases, this same weakness appears relevant to customary

landowners when it comes to negotiating leasing arrangements.

Australia's assistance

17.16

While referring to the importance of land reform to economic development

in Pacific island countries, some witnesses recognised the difficulties and

sensitivities surrounding the issue. With regard to Australian assistance in

this area, AID/WATCH noted that 'Any Australian government involvement with

changes to land ownership systems in the Pacific needs to be carefully considered'.[28]

17.17

The Australian Government acknowledges that land policy in the Pacific

is a complex and sensitive issue which must be driven and shaped by Pacific

governments and communities and not by donor countries.[29]

It has allocated $54 million over four years to a Pacific Land Program. The

program aims to strengthen land systems to enable greater levels of social and

economic development and reduce the potential for instability due to

land-related conflict'.[30]

The Parliamentary Secretary for International Development Assistance, the Hon

Mr Bob McMullan MP, told a Pacific Land Conference that Australia would:

...support partner government initiatives that seek to

strengthen land departments, and that seek to find new ways of making customary

land work for customary owners and the national welfare, while maintaining the

integrity of traditional tenure.[31]

17.18

He stressed that host countries would take the lead and Australia's role

would be 'confined to that of supporting these initiatives'.[32]

In this context, he explained that Australia would provide:

-

assistance for the framing of stronger legislation on tenure

security and mechanisms for informed consent for customary owners involved in

land negotiations;

-

support to improve systems to resolve disputes;

-

training for land professionals and semi-professionals in areas

such as surveying, land use planning, valuing, real estate and the law; and

-

on a regional level, help to countries wanting to respond to the

challenges and opportunities associated with rapid urbanisation.[33]

17.19

With this in mind, AusAID produced a comprehensive publication, Making

Land Work, as 'an information source for countries wanting to undertake, or

who are already undertaking, land policy reform'.[34]

17.20

In the previous section, the committee mentioned concerns about the

capacity of customary landowners to negotiate land tenure arrangements and cited

experiences in Vanuatu. In this regard, the committee notes Mr McMullan's

assurances that Australia would provide assistance for developing mechanisms around

'informed consent of customary landowners in negotiations with investors and

developers'.[35]

17.21

A number of witnesses commended the government's approach to land reform

in Pacific island countries. AID/WATCH and the Australian Agency for

International Development (ACFID) referred to the statements by Mr McMullan as

a positive indication of Australia's intention to 'listen to Pacific community

voices' and adhere to two fundamental principles:

-

Australia will only support reforms that recognise the continuing

importance of customary tenure; and

-

land policy reform must be driven by Pacific island governments and

communities, not by donors.[36]

17.22

Ms Hayward-Jones acknowledged the work undertaken recently by AusAID on

land tenure as 'fairly well received'.[37]

She indicated that exploring options and ideas on ways to manage land ownership

issues through education, debate and workshops would be one way of offering

assistance.[38]

The Australia Fiji Business Council noted that generally AusAID's contribution

on possible reforms to enable better economic usage of land was 'very

worthwhile'. According to the Council, this work in time may lead 'to a more

stable and predictable environment for all parties', but it needs 'to continue

in partnership with Pacific stakeholders'.[39]

17.23

Some witnesses were either critical of Australian assistance or more

definite in identifying areas where Australia could contribute to land reform. Professor

Hughes argued:

We have not put in the intellectual resources to try to

persuade people that land tenure is important. We have not put in the aid

sources for cadastral surveys so that villages would know what land is theirs

to divide. We have not supplied the aid for that. In Fiji, it exists. But in

most other islands it does not, and it certainly does not exist in Papua New

Guinea. We have failed to do our part in the land problem.[40]

17.24

Professor Moore suggested that Australia should be putting more effort

into advising Pacific island countries on 'how to deal with customary land

tenure'.[41]

The Centre for Independent Studies noted that land surveys would be 'an ideal

task for Australian aid since they are financially and technically demanding'.[42]

According to ANZ:

Australia could consider providing assistance to help PNG (and other Pacific Island states) develop arbitration and mediation procedures for land

disputes which would make the administration of land law more efficient.[43]

17.25

Mr Hodgson, Australia Pacific Islands Business Council, liked the idea

of an arbitration structure because, 'it brings a degree of formality to the

quite casual way in which Solomon Islands matters are dealt with'. He was unsure

about whether the government would think that Australia was interfering. He

said that if it were 'handled well and diplomatically they may well see it as

something that is helpful'. He concluded:

I do not think anywhere near enough time has been devoted

towards trying to work out a way in which customary land can be used as an

asset to borrow against, lease or do what you like with it. I do not think

enough time has been spent in that thinking process'.[44]

17.26

Mr Noakes believed that there could be some value in providing

assistance to foreign investors from countries such as Australia to develop 'an

understanding of traditional practices and local authority structures and

loyalties, land ownership and land use'.[45]

Summary

17.27

The committee recognises the work that Australia is doing in the area of

land tenure. Clearly, while some witnesses acknowledged Australia's assistance

with land tenure reform in the region as 'well received or worthwhile', some

saw room for an improved role for Australia in this area.

Access to credit and financial services

17.28

Many businesses, especially the local small to medium enterprises, need access

to credit to start up or expand their business. The willingness to lend money

for commercial undertakings in Pacific island countries depends on a risk

assessment that takes account of many factors such as likely economic

prospects, the quality of economic infrastructure, service delivery, the

regulatory environment, political stability, law and order and land ownership.

17.29

Unfortunately, because of deficiencies in these areas, many Pacific island

countries are deemed to be difficult places to do business, which makes lenders

reluctant to finance enterprises. For example, Qantas noted that given the

weakness of aviation and related infrastructure in many parts of the region,

investors are unwilling to commit funds for construction of hotels and other

tourist plant.[46]

The Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat drew a similar conclusion about the

uncertain financial environment in Pacific island countries that requires

commercial banks to protect their interests by imposing loan conditions that

severely limit opportunities for investors to access finance.[47]

17.30

The small populations in Pacific island countries with a high proportion

of people working in the subsistence economy also limits access to finance. But

even those in the SME sector of the largest Pacific island countries have

problems obtaining credit. Mr Clarke noted that PNG does not have a

'significant middle class'—it 'tends to be at a subsistence level or at a very

small scale' and without access to credit.[48]

He said, 'Some of those companies will not quite fall within the minimum criteria

to attract commercial bank loans, and so there is a dearth of equity

capital—SME start-up capital'.[49]

17.31

Microfinance, which offers a full range of financial services to the

poor including savings, loans, insurance and money transfer services, is one way

of overcoming the disadvantages now experienced by many people living in the

region. The Foundation for Development Cooperation noted that the number of

microfinance programs had increased in Pacific island countries in recent

years. It informed the committee, however, that most of the schemes had not

been successful due to their limited outreach and poor access to financial

services, particularly for the most disadvantaged living in rural areas. In its

view, microfinance programs in the region 'should provide business and

technical training for their clients, or coordinate their activities with other

programs that provide such training'.[50]

A UNDP study found that only around 20 per cent of the population of Kiribati,

Tuvalu, Samoa, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu had access to financial services.[51]

17.32

AusAID acknowledged that access to finance was a problem for parts of

economies of Pacific island countries but agreed with the observation that the

difficulty was more with access to financial services. Dr Lake explained:

In many parts of the Pacific, when people are moving from

subsistence agriculture into the marginal cash economy, they save for school

fees, health costs and things like that. What they want is financial services,

in which case they can put the money in to save and then take it out when they

need it. Microfinance can be an important part of a broader package of

financial services, and people usually want the financial services.[52]

17.33

In her view, the financial services sector in the region was 'pretty

thin and narrow'. Importantly, she identified transport and communication

networks as a means of enhancing and expanding this service. For example, she

cited improved road services in Malaita where vans are now travelling out to

rural areas offering banking services, and the use of mobile phones to transfer

money around the country.[53]

Telecommunications technology, in particular, is opening up new opportunities

to extend financial services to the 'unbanked'.[54]

Committee view

17.34

Many Pacific Islanders suffer economically from poor access to financial

services. The committee recognises that microfinance offers great potential to

extend the reach of these services to the many currently excluded from them. It

also notes that success in extending the frontiers of financial services also depends

on improvements in roads and ICT services.

Australia's assistance

17.35

In previous chapters, the committee has noted the contribution

that Australia is making to assist Pacific island countries create a secure and

friendly business environment. All these measures designed to improve economic

infrastructure, the delivery of essential services and overall governance will

also make the business environment in Pacific island countries more attractive

to lending institutions. Nonetheless, access to credit and to financial

services remains a major impediment to business.

17.36

Information contained on AusAID's website states that Australia will provide

$20.5 million over six years to pilot an Enterprise Challenge Fund (ECF) for

the Pacific and South-East Asia to stimulate economic growth. The fund provides

an opportunity for private-sector businesses to participate in open competition

for matching grants to finance commercially viable business projects. It also

intends to ensure that the poor are included in the benefits and opportunities

provided by growth. Through open competition, the fund would award grants of

$100,000 to $1.5 million to 'business projects with pro-poor outcomes and that

cannot obtain financing from commercial source'. According to AusAID:

At least 50 per cent of the project costs must be met by the

partner business, and all projects must be commercially self-sustaining within

three years.[55]

17.37

AusAID recently announced details of its first two successful grantees. One

of them, Nature’s Way Cooperative (Fiji) Ltd, an expansion of a fruit quarantine

facility, was awarded $263,000. This contribution will enable the cooperative

to expand its fruit exports to improve the livelihoods of approximately 1,200

rural people in Western Viti Levu.[56]

Nature's Way Cooperative in Fiji, funded by AusAID's

Enterprise Challenge Fund, aims to improve marketing services for the Fiji

fruit and vegetable export industry and expand quarantine treatment facilities

(image courtesy of Coffey International Development).

17.38

The three Business Councils recognised the fund as a step in the right

direction. They noted, however, that the major drawback with the fund was that

a successful applicant was required 'to be in position to put up $100,000 in

equity or kind towards the project being funded. In its assessment, there would

be cases where good business proposals will fail to qualify for the ECF grant

due to this requirement'.[57]

17.39

Mr Noakes also referred to the ECF but noted that 'only two of the first

30-odd applications got across the line'. In his opinion, something must be wrong

with the mechanism 'when some very good applications which could have had a lot

of benefit in communities just did not get up'. He believed that AusAID was

still coming to terms 'with mechanisms to help stimulate and assist the private

sector' and had 'not quite got there yet'.[58]

17.40

The committee notes this criticism of the Enterprise Challenge Fund. It

also notes the evidence that the availability of financial services is a major

constraint for Pacific islanders.

17.41

In his 2009–10 Budget Statement, the Minister for Foreign Affairs announced

that Australia would facilitate economic growth through expanded support for

microfinance activities in both urban and rural areas. According to the

minister, new assistance would include increasing support activities in the

Pacific and PNG drawing on partnerships with NGOs, regional network

organisations and the private sector. No mention was made of specific programs

or activities or of the partnerships with NGOs and the private sector. The

Pacific Partnerships for Development are also intended to be a mechanism

whereby private sector development would be enhanced through better access to

microfinance.[59]

Currently, however, they shed no light on activities that are intended to

achieve this objective.

17.42

Concerned about the lack of detail on the type of assistance Australia

is providing in the area of microfinance, the committee wrote to AusAID seeking

more information. AusAID informed the committee that activities currently and

previously funded by Australia included the provision of enterprise development

and financial literacy training across a number of Pacific island countries and

expanding banking services to remote areas in the Pacific through mobile

banking.[60]

17.43

ANZ informed the committee of its work to raise the level of financial

literacy and to provide financial services to those currently out of reach of

the traditional banking system. It runs a program called 'Banking the un-banked'

in the region which:

...delivers basic, affordable and reliable banking services to

remote and disadvantaged communities in the region, in partnership with the United

Nations Development Programme (UNDP), to provide financial literacy education.[61]

17.44

It reported that since launching the program in October 2004, 75,000 previously

unbanked rural people in a number of Pacific countries have opened savings

accounts. ANZ also offers micro-loans to regular savers and explained that a

micro-loan of $100 'can start a small business which in turn can lead to

increased income and better living conditions'.[62]

It noted further:

Developing infrastructure in Pacific economies so communities

have access to a range of financial products and services is important to the

communities in which they are offered as well as the economy more broadly.

However, efforts in this area will have a better chance of succeeding if

individuals and communities are provided with the financial education needed to

understand both the benefits and downsides of easier access to financial

services.[63]

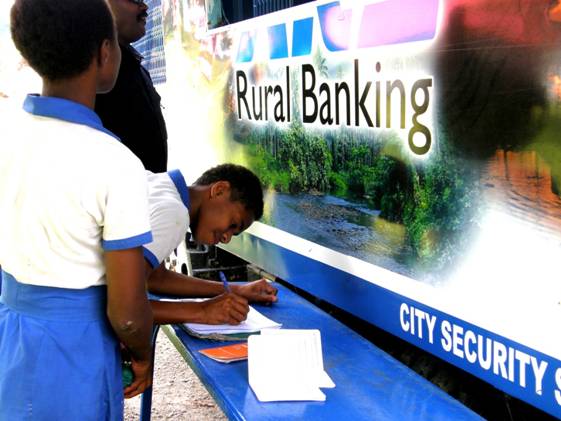

The ANZ Bank has established

mobile banking services in Fiji. The services are popular in remote and rural

Pacific island communities (image courtesy of Islands Business, published with

ANZ's approval).

17.45

ANZ cited its work to improve financial literacy in the region as an

area in which it could work with the Australian Government to deliver improved

social and economic outcomes in the Pacific.[64]

Committee view

17.46

The committee notes the establishment of the Enterprise Challenge Fund and

the criticism about its limited application. It also recognises that access to

financial services is a major constraint to economic development in Pacific

island countries. Apart from general references to Australia's support for

microfinance, the committee has little evidence that this aspect of Australia's

assistance forms part of a coherent assistance framework. The committee

believes that there is much scope for the Australian Government to improve its

contribution to microfinance in Pacific island countries. The committee,

however, acknowledges and commends the work that ANZ is doing in the region to

provide financial services and improve financial literacy.

Recommendation 13

17.47 The committee recommends that the Australian Government establish a

strategic framework that encourages the private sector to get involved in

providing microfinance and other financial services in the Pacific island

countries.

17.48

In the following part of this report, the committee brings

together the evidence presented so far to consider the effectiveness of

Australia's assistance and how Australia could do better to help Pacific island

countries achieve economic growth and sustainable development.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page