Chapter 11 - The IGADF and the Defence Force Ombudsman

11.1

The previous chapters identified a long list of

perceived flaws in the conduct of routine and investigating officer inquiries

and inquires undertaken as part of a review or a redress of grievance. One of

the main concerns was the apparent lack of independence. There are now a number

of review mechanisms that stand outside the chain of command—the newly created

Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force and the Defence Force

Ombudsman—that are intended to provide a greater degree of objectivity and

impartiality to the military justice system. This chapter considers their roles

and functions and the contribution they make to the effectiveness of this

system.

Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force (IGADF)

11.2

The ADF looks to the newly appointed Inspector-General

of the Australian Defence Force (IGADF) to counter criticisms about the

perceived lack of independence in its administrative system. Its establishment

stems from recommendations contained in the Burchett Report which suggested

that:

A Military Inspector General independent of the normal chain of

command and answering directly to the CDF would provide greater assurance of

independence for those cases where complaints do need to be brought forward. [718]

11.3

The main function of the IGADF is to provide the CDF

with an internal review of the military justice system, separate from the

normal chain of command, and 'to provide an avenue by which failures in the

system—systemic or otherwise—may be examined.'[719] According to General

Cosgrove, recent initiatives such as the

establishment of an IGADF provide an additional 'failsafe layer' in the

military justice system.[720] He stated

that the IGADF offers an opportunity for independent review. [721]

The Independence

of the IGADF

11.4

The Burchett Report stressed that its proposed OIGADF

'must be, and be plainly seen to be, independent of the normal chain of command'.

It went on to state:

It should be directly under the command of the CDF. Thus it will

be seen that the Military Inspector General is not susceptible to undue

influence by anyone in a chain of command. This does not mean that the position

would have to be completely outside the Australian Defence Force and the

Department of Defence...It does mean, however, that the Military Inspector

General should be seen as a distinct entity from the three Services and from

the principal joint organisations, under which all military personnel are

administered.[722]

11.5

The Burchett Report stated further that:

The Military Inspector General will require to be a figure who

can actually maintain independence. For that reason, the appointee should

ideally not be a person who could be thought to have career expectations in

Defence. Of course, the appointee should have a close familiarity with the

Australian Defence Force environment or should be at the apex of a highly

expert staff with that familiarity. An understanding of the military justice

system would be essential.[723]

11.6

The appointment of the IGADF is in keeping with the

findings of the Burchett report. He or she does not hold military rank although

for administrative purposes the position equates with Senior Executive Service

Band 2. He or she reports to the CDF and, according to Defence Instructions,

'is independent of the normal ADF and public service chain of command or line

management'. Defence Instructions advise that:

This arrangement is intended to allow the IGADF to undertake

his/her duties impartially and to counter any perceptions of undue influence

arising in relation to matters under consideration by the IGADF.[724]

11.7

They make clear that the 'establishment of the OIGADF

is not intended to duplicate or displace the functions of other such agencies

or appointments but rather should be regarded as complementary to them'. The

IGADF's role is unique in that, unlike other agencies, its focus is on the

military justice system as a whole.[725]

11.8

In response to committee concerns about the independence

of the IGADF, Mr Earley

noted:

Mr Burchett’s

visions and his recommendations were never that the office of IGADF would be

completely independent in the sense of being external to the defence department

entirely, like the Ombudsman. He envisaged it being independent of the normal

chain of command but responsible to the CDF—and only the CDF. I am not responsible

to any of the service chiefs, only to General Cosgrove.[726]

11.9

He explained further that the office does not purport

to be, and was never intended to be, independent in the sense of being

completely external to the Defence Organisation. In his opinion:

Given its role, the present arrangements of being aside from and

yet at arms-length to and not divorced from the ADF offers advantages which, in

my view, are unlikely to be available had the office been established

completely externally. This includes the ability to move freely within the

Defence Organisation to go directly to the relevant area of interest and to

operate with and under the authority of the CDF. In a hierarchical structured

organisation such as the ADF, they are pretty important considerations. They

are important, in my view, because they greatly assist the office to perform

its function in a way which lessens the risk of resentment arising from a lack

of awareness of cultural factors while at the same time allowing an arms-length

impartial approach.[727]

11.10

The committee notes that the IGADF does not have

executive authority to implement measures arising out of his or her

investigations. The IGADF's only authority is 'to make recommendations to other

authorities who may remedy the matter'. The IGADF may, however, report the

outcome of his or her inquiry, including the adequacies of any responses, to

the CDF.[728] The committee is

concerned that there are inadequate measures in place that would hold the CDF

publicly accountable should he or she fail to act in part or in full on a

recommendation by the IGADF. For example, there is no requirement for the CDF

to provide written explanations to the IGADF for rejecting recommendations which

would for example enable the IGADF to comment on any concerns related to such

matters in his or her annual report.

11.11

The committee believes that such a requirement for the

CDF to notify the IGADF in writing where the CDF does not accept a

recommendation should be explicitly stated in paragraph 34 of the Defence

Instructions (General): Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force—role,

functions and responsibilities.

11.12

In the context of his status as an independent body,

the IGADF elaborated on the nature of his employment conditions:

...at CDF’s direction, action is being taken to move my position

of IG ADF

from a contractual basis, where it now lies, to a legislative basis. The

intention is that the basic role, structure and reporting arrangements, which

have actually proven to be quite effective, will remain as presently established,

except that the authority for it will have a legislative or statutory basis at

some time in the future. I think the earliest, optimistically speaking, that

that might happen is probably legislation to go before the autumn sittings next

year...The object there is to enhance the perception and the reality that the IG

ADF and his office are independent from the

normal chain of command.[729]

11.13

In May 2005, when asked about progress toward placing

the appointment and employment conditions of the IGADF on a statutory basis, Mr

Mark Cunliffe,

Head Defence Legal, informed the committee that a bill was proposed for

introduction in the June 2005 parliamentary sittings. When pressed on this

matter, Mr Cunliffe

stated that he did not know exactly how much of the bill was drafted but it

'certainly has been in various draft versions.' He went on to say that 'There

have been policy clearance procedures in place in relation to some parts and

that is continuing'. The Minister for Defence noted that it has taken four

years of drafting to get to this point which, in his view, was 'a very long

time.'[730]

11.14

As observed by the minister the progress toward moving

the IGADF from a contractual basis to a legislative one has been slow. This

delay in placing the IGADF's appointment and employment conditions on a

statutory base weakens any attempt by the Government and the ADF to convey a

positive message about the purported independence of the IGADF.

The accessibility of the IGADF

11.15

In establishing the IGADF, the Government and the ADF

recognised that there may be occasions when individuals feel they are unable or

are reluctant to report their concerns through the chain of command. Even so,

the office takes the approach that it does not offer 'a short cut for

complainants'. Its objective is:

to allow and encourage the normal systems for dealing with

failures in the military justice system to operate first. If there is some

specific reason why they cannot or if a member feels that for some particular

reason they are unable to access the normal systems, that brings into being the

sort of role that we can play.[731]

11.16

Submissions may be made to the IGADF where:

-

the person making the submission believes that

they, or any other person, may be victimised, discriminated against or

disadvantaged in some way if they make a report through the normal means;

-

the person making the submission has no

confidence that the chain of command will properly deal with their Military

Justice concern, for instance, if the chain of command is perceived to be part

of the problem; or

-

the established complaint mechanisms for

specific Military Justice issues or the chain of command have been tried and

have failed to address properly the problem.[732]

11.17

Persons may make submissions whether of a systemic or

individual nature that relate to the processes and arrangements under which

military justice is administered. They may be concerned with matters such as:

-

procedural fairness/denial of natural justice;

-

avoidance of due process and specified procedures;

-

victimisation, harassment, threats,

intimidation, bullying and bastardisation; and

-

general suggestions regarding the military

justice system particularly in relation to examples of systemic failure and/or

suggestions for improvement.[733]

11.18

Under this reporting framework, individuals may make

anonymous submissions. The Manual notes, however, that:

...such submissions are regarded as being informative rather than

evidentiary which means that the scope for taking further action may be more

limited than if the person makes their identity known to the IGADF staff.

Nonetheless investigation of the allegations will be assisted by the provision

of as much information as possible about the subject of the complaint. Persons

who make anonymous submissions cannot, since their identity is unknown to the

IGADF, be provided with feedback information concerning the progress and

outcome of their submission.[734]

Protection of those making

submissions to the IGADF

11.19

Defence Instructions recognise that in some cases

persons making submissions to the IGADF may fear for their safety, security,

career or general well-being. It advises that support and protection mechanisms

are available to assist in these circumstances and that IGADF staff 'will

liaise directly with the person in order to best determine the nature and level

of support and protection required in each case'.[735]

11.20

The committee refers to the Defence Whistleblowers

Scheme which also provides for a person to be assigned to a case to ensure that

the person making a report does not suffer reprisals on account of making a

report. It is concerned that confusion may be created about who has

responsibility for the protection of people reporting wrongdoing or making a

complaint. It has suggested that the reporting system be streamlined.

Delays in processing a grievance

11.21

The IGADF, which was established in January 2003,

started from scratch and, according to the IGADF, early indications are that it

is beginning 'to make a positive difference and is shaping up...to be a most

worthwhile and important initiative for military justice in the ADF'.[736]

11.22

Because the position is newly created, few witnesses

had used the new system and were not able to make any substantial comments

about the role and function of the IGADF. A number approved of the

establishment of the office with one observing that 'it appears that

investigations may take place without the chain of command influence that is

present for the ROG process.' Even so, she identified a number of potential

problems, in particular the requirement for the ROG process to be exhausted

before the IGADF can address a matter.[737]

Given the delays that afflict the ROG process, complainants may still have to

endure prolonged periods before final decisions are made causing what one

witness described as 'enormous stress and heartache to the member involved and

their family'.[738]

11.23

In establishing the IGADF, no serious steps were taken

to break the cycle of delay that frustrates the ROG process such as empowering

the IGADF to intervene in order to expedite the conclusion of an ROG that has

stalled in the system. Paragraphs 17 or 18 of the Instructions Manual could

state explicitly that a person may submit their grievance to the IGADF if its

progress has been delayed and could even stipulate the time at which the IGADF

could intervene.

Early days for the IGADF

11.24

The committee acknowledges that it is far too early to

evaluate whether the establishment of the IGADF will prove to be an effective

review mechanism. It notes the heavy emphasis placed on settling matters under

the administrative system using the chain of command, line management or other

specialised agencies at the lowest possible level. The committee is concerned

that unless the IGADF shows a willingness to act and does act decisively and

promptly to accept submissions that have legitimate grounds for by-passing the

line of command, it will lose credibility as an effective force in the

administrative system.

11.25

As noted previously, the position of IGADF has only

recently been established and it is too early to make any certain judgements

about its effectiveness. One witness, however, who had lodged a submission with

the IGADF was disappointed and noted:

-

there was no initial confirmation of receipt of

submission;

-

the lack of response became a regular feature of

interaction with some requests left unanswered;

-

the requirement to resubmit submission as the

original could not be located;

-

case officer had a poor understanding of the

case; and

-

the IGADF could do nothing until the ROG process

had been finalised.[739]

11.26

The committee believes that, although these could be

examples of teething problems, the criticism underlines the importance of

monitoring the performance of the IGADF.

11.27

In light of the failings of the current administrative

system as identified in this report, one of the major challenges facing the

IGADF is to win the trust and confidence of members of the ADF. Any suspicion

that the office is susceptible to the influences of senior levels in the ADF

will undermine its credibility. It must be seen to stand apart from the command

structure, to be committed to the principles of procedural fairness and to be a

professional organisation with adequate resources and staff equipped with the

skills and training necessary to process grievances or complaints competently

and expeditiously. This is a sound reason for providing the IGADF with

effective reporting procedures.

Reporting obligations

11.28

A reporting regime that is transparent and promotes

accountability would greatly improve the perceived independence of the Office

of the IGADF. As noted earlier, the IGADF reports directly to the CDF. The

IGADF is required to provide the CDF with internal audit and review of the

military justice system independent of the ordinary chain of command. [740]

There does not appear, however, to be any adequate avenue for the IGADF to air

his or her concerns about the military justice system to any authority other

than the CDF.

11.29

Mr Earley

informed the committee that the original intention was that there would not be

an annual report to the parliament. It has now been agreed, however, that there

will be a section in the annual Defence Report which will relate to the office.[741]

11.30

The committee argues for a separate IGADF's report

independent of Defence's annual report. It believes that the reporting

obligations placed on the IGADF must allow public scrutiny. The current

reporting requirements do not offer any real guarantees that the information

provided would be sufficient to allow effective parliamentary scrutiny. The

committee refers to the Defence Force Ombudsman's report for the years 2000–01

and 2001–02. They provide a critical and comprehensive assessment of the

complaints it received as well as a number of case studies which provide some

insight into the nature of the complaints. This report provides an ideal model

for the IGADF.

Measures taken to improve the

competency of investigating officers

11.31

The committee notes the initiative taken by the IGADF

to improve the competence of investigating officers. Defence Instructions state

that the IGADF:

...will maintain a register of persons considered suitable by

training and/or experience to act as investigating officers, or members of

administrative inquiries. Personnel listed in the register may be used by the

IGADF for administrative investigations, but will also be available on request

to other Appointing Authorities including Commanding Officers. The objective is

to establish a pool of suitably qualified persons who understand the

administrative inquiry process and the attendant legal and procedural

obligations and who are capable of conducting, or taking part in, an

administrative inquiry under the Defence (Inquiry) Regulations 1985.[742]

11.32

The IGADF is sponsoring a pilot training course for

administrative inquiry officers with the object of producing a 'larger pool of

officers with a good understanding of how to go about conducting an

administrative inquiry'.[743] It has

established a register of inquiry officers drawn from the three services. The

IGADF has also under development, and has volunteered to manage, a reporting

system whereby all administrative inquiries above the level of investigating

officer are to be centrally reported to the office of the IGADF. Mr

Earley told the committee:

...the implementation of recommendations and outcomes from those

inquiries could undergo some scrutiny and some monitoring, which currently is a

bit of a difficult area and, as I think most people would agree, needs some

attention.[744]

11.33

The committee endorses the measures taken to improve

the competence of investigating officers, to develop a register of

investigators, and to establish a central reporting system for administrative

inquiries (see recommendation 29, para. 11.67)

Other external review mechanisms

11.34

In addition to the internal review mechanisms available

to ADF members, there are a number of external review mechanisms: the Defence

Force Ombudsman (DFO), the Privacy Commissioner and the Human Rights and Equal

Opportunity Commission. Furthermore, conduct and decision making in the ADF may

be subjected to external judicial review in the Federal Court and thereafter in

the High Court.[745]

Defence Force Ombudsman (DFO)

11.35

General Cosgrove

expressed his concern with proposals that would move involvement in the

military justice system away from the command structure:

If disciplinary action is taken in respect of an offence, then

there is also legal protection, such as the right to a defence, under the

Defence Force Discipline Act. We cannot afford to breed a generation of risk

adverse commanders who are so concerned about being second-guessed that they do

not act at all. Our junior leaders are trained to demonstrate their initiative

and to exercise a high level of responsibility. They have shown themselves to

be very good at it. They know that with responsibility comes accountability. The

more we shift the responsibility for military justice away from the chain of

command, the more we risk undermining both systems.[746]

11.36

Even so, he acknowledged that 'despite the Forces' best

efforts some cases of poor administration will inevitably occur'. According to

the CDF, in such cases, the Ombudsman is 'a valuable external point of review

for ADF members unsatisfied with the results or conduct of a grievance

investigation, and the support of that office continues to be appreciated.'

11.37

In 1983 the Ombudsman Amendment Bill was passed

creating a statutory office of Defence Force Ombudsman with much the same

powers as the Commonwealth Ombudsman. It recognised that servicemen and women

at that time did not have access to complaint handling mechanisms that other

Australians in civilian employment enjoy such as representation through union membership

or access to arbitration processes.[747]

The legislation was intended to provide an important step forward in the

conditions of employment for ADF members. Mr Willis, then Minister for

Employment and Industrial Relations and Minister assisting the Prime Minister

for Public Service Matters, informed the House that:

Servicemen and women differ from most other Australians in that

their relations with their employers can extend into almost every aspect of

their lives. It is in the nature of Defence Force service that members do not

have the advantage of external grievance mechanisms typical in civil

employment. With the creation of a Defence Force Ombudsman an independent

avenue for the review of grievances will be established.[748]

11.38

The amendment proposed that the office of Defence Force

Ombudsman be established within the Ombudsman Act as a complement to the

Ombudsman's jurisdiction. The office, however, was to be identifiable and

distinct.[749] It conferred on the

Defence Force Ombudsman the function to investigate, either on complaint being

made or of his or her own motion, administrative actions related to or arising

out of a person's service in the Defence Force.

11.39

The legislation acknowledged that 'For effective

management in the Defence Force, officers should usually hear and have the

first opportunity to remedy the grievances of those under their command'.[750] It envisaged that the Defence Force

Ombudsman would complement, rather than compete with, existing internal redress

procedures.

Independence

of the DFO

11.40

One of the major strengths of the Defence Force

Ombudsman is its independence from the Defence Force. Mr

Ron Brent,

Deputy Ombudsman, explained:

...we are independent and impartial. That very significantly

changes the character of the review not just because it gives us a capacity to

view issues with a freshness and an independence that you just cannot get with

the system but also because it presents to the complainant an impartial and

dispassionate review so that, even if the outcome is that we uphold the

original decision, the fact that we have come to that conclusion can be a

significant factor in satisfying the complainant that they have been fairly

treated. One of the features of the Ombudsman’s office is that we are

independent and do carry that sort of status and credibility.[751]

11.41

He also identified a second strength:

...while the rate at which we find complaints to be upheld is

relatively low, often the complaints that we do find upheld are very

significant. Therefore, the measure of our value added is not in the percentage

of cases where we find a mistake; the measure is in looking at the nature of

the mistakes and at the quality of the contribution we can make. Often the

issue will be a more significant problem because, were it a simple problem, the

internal grievance processes would have been able to deal with it. Where the

problem lies in the character of the system or in the character of the

structures, the administrative processes or the legislation, we become more

significant.[752]

11.42

Although the Defence Force Ombudsman jurisdiction is

limited to making recommendations, he was confident that 'the legitimacy of our

involvement in that area has been accepted'.[753]

He noted that his role of Defence Force Ombudsman was not well known in the

forces.[754]

Constraints on the DFO

11.43

The current Defence Force Ombudsman, Professor

John McMillan,

was of the view that the Ombudsman Act imposed some constraints on the

jurisdiction of his office. He explained:

One is that our jurisdiction does not extend to action taken in

connection with proceedings against a member of the Defence Force for a breach

being a disciplinary offence, so matters in connection with proceedings for a

disciplinary offence are beyond our jurisdiction. That is an elastic concept

and by and large we have interpreted it fairly narrowly and declined

jurisdiction, for example, once a charge has been preferred against a person.

But certainly we interpret our jurisdiction as extending to the inquiries that,

for example, can sometimes lead up to or culminate in disciplinary proceedings

being brought. And, equally, we interpret our jurisdiction as extending to the

administrative actions that are sometimes taken subsequent to or in

implementation of decisions made in disciplinary proceedings. [755]

11.44

He also noted, as a further limitation, the statutory

presumption in favour of a person first using the internal processes for

redress of grievance before the Ombudsman accepts a complaint and investigates.

He explained:

The act says that the Ombudsman can investigate in special

circumstances or can investigate once 29 days have expired since the redress of

grievance process commenced. In fact...the redress of grievance process can

sometimes take a lot longer, so our investigations are commonly delayed for

some period by that statutory presumption in the act. We received 722

complaints that fell within the Defence Force Ombudsman role last year.[756]

11.45

The Annual Report noted that the Ombudsman's 2004

Client Satisfaction Survey highlighted that complainants in the Defence Force

Ombudsman jurisdiction are 'generally less satisfied with our service than

complainants in other jurisdictions'.[757]

This is on top of the delays and frustrations experienced in the internal

investigation and review processes.

11.46

Witnesses who remarked on the role of the Defence Force

Ombudsman identified a number of shortcomings acknowledged by the Ombudsman

himself including the inability to investigate a complaint until a ROG process

is finalised and the lack of authority to enforce recommendations.[758] The committee notes that this lack

of authority is typical of functions of most Ombudsmen. One witness who sought

to have his complaint dealt with by the Defence Force Ombudsman was told he

would be asked to use the military justice system first. In his view:

Having to go through the Military Chain of Command first before

the Defence Ombudsman deprives staff of the ability to have an independent

agency investigate the matter. The situation allows the Chain of Command to

cement its position and delay any potentially damaging findings until after the

CO/OC have left the job or been promoted.[759]

11.47

Another witness contacted the Defence Force Ombudsman

on three separate occasions for help in the progression of his ROG. On each

occasion, he was advised that the Ombudsman could not act until the RAAF had

processed and adjudicated on the ROG notwithstanding the effects that the undue

delay was causing.[760]

11.48

The CDF and the Defence Force Ombudsman agreed to

conduct a joint review of the ROG system with the intention to identify

strategies to refine the system.[761]

11.49

The joint review of the ROG system, undertaken by the

Department of Defence and the Office of the Ombudsman, recently made public its

findings. It underlined many of the conclusions reached in this report. For

example, it considered that the rapid increase in complaint handling avenues

had 'vastly added to the complexity of managing and administering complaints in

Defence'.[762] The review stated:

Very few complainants and managers appear to understand all of

these avenues. Many of these processes have the mandate to examine similar

issues, and some may result in executive action such as disciplinary

proceedings or sanctions. The Review found that this myriad of systems is not

only complex and somewhat bewildering to the user, it must also result in less

than optimal use of resources and inefficiencies. The systems have grown in a

piecemeal and ad hoc fashion. The current ROG system now lies uncertainly

within a complex and poorly understood network of inter-linked processes and

mechanisms that make up the military justice system.

11.50

The review made a number of recommendations designed

to:

-

expand the role of the CRA to include

leadership, direction and coordination of all Defence's formal complaint

handling systems;

-

develop a common information system for

complaint management with the ability to provide information in a form that

will support Defence wide reporting including information required by the

Inspector General (ADF)

-

co-locate where possible and centrally manage

the numerous agencies that deal with complaints—DEO, Army Fair Go Hotline, Army

Land Command Sensitive and Unacceptable Behaviour and Incident Management Section,

Directorate of Alternative Dispute Resolution and Conflict Management, Navy's

Sexual Offence Support Persons program;

-

enhance the process of preliminary assessment by

CRA to prevent delays;

-

expand the role of CRA to measure, monitor and

report the total time taken to address each complaint;

-

impose strict timelines for ROGs to be lodged

well in advance of an advised termination date;

-

improve the approach to prioritisation of ROGs;

-

improve the coordination of training in

administrative investigations across all ADF courses that currently include

elements of investigation and administrative law.

11.51

The committee accepts that the implementation of the

recommendations may go some way to address the problems identified in the ROG

process. The committee, however, is not confident that the recommendations go

far enough especially in light of the failure of initiatives, introduced over

the past decade, to redress the problems. The committee, therefore, stands by

its view that the time for tinkering with the complaint handling mechanisms is

over and a comprehensive reform of the ROG process is required.

Courts and Commissions

11.52

Members may apply to the courts or other institutions

such as the HREOC to seek redress from adverse administrative action. The terms

of reference did not mention these external review mechanisms and they

attracted little comment from submitters. The report notes but does not examine

their important role in the military justice system.

11.53

The committee did, however, receive a disturbing

allegation that RAAF officers had threatened to take action against a member

should that member proceed with court action.[763]

The use of intimidation by ADF members to dissuade others from pursuing a

complaint or grievance debases the military justice system. The committee has

already voiced its concern about the prevalence of unlawful reprisals and urged

the ADF to take firm steps to remedy this problem (see paras 7.39–7.59 and 7.76–7.80).

Summary

11.54

This report has identified serious problems with the

administrative component of the military justice system. The problems emerge at

the very earliest stage of reporting a complaint or lodging a grievance and

carry through into the final stages of review or appeal. The problems are not

new—they have dogged the system for many years—nor are they confined to

specific ranks or areas of the Forces. Young recruits and senior officers,

female and male members across the three services engaged in the full range of

military activities have given evidence before the committee raising their

concerns about the military justice system.

11.55

The problems identified by these witnesses are not

unique to the ADF. Many countries have grappled with similar difficulties and

have taken steps to reform their systems. The Canadian initiatives have particular

significance for the ADF.

Looking forward

11.56

The committee is impressed with the reforms that have

taken place in the Canadian Forces on the redress of grievance process. The

Canadian reforms were intended to compensate for shortcomings in the military

justice system—notably a grievance process tied closely to the chain of command

with no adequate external checks and a lack of unions or employee associations

to represent the interests of members. Indeed, the Canadian reforms address issues

similar to those that plague the Australian system—confusion due to the number

of bodies that handle complaints or grievances, the perceived lack of

independence in the investigators and decision makers and delays in processing

a complaint.

11.57

In December 1998, the Canadian Forces Grievance Board

(CFGB), an independent, arms-length organisation, was created through

amendments to the National Defence Act. Prior

to these amendments, a grievance could have passed through multiple levels of

review. The Act now provides for two levels of authority in reviewing

grievances and has effectively made the process 'simpler and shorter'.[764]

11.58

The first level is the initial authority where the CO

takes responsibility for reviewing the grievance and granting redress. A person

not satisfied with a decision at this level may submit an application for

review to the Chief of the Defence Staff. At this second level, grievances,

except those related to matters such as performance appraisals, promotions,

postings, training and other career issues, are referred on to the CFGB. Thus,

the CDF refers to the Grievance Board any grievance relating to matters such as

administrative action resulting in the forfeiture of, or deductions from, pay

and allowances, reversion to a lower rank or release from the Canadian Forces.

Other grievances referred to the Board include matters such as the application

or interpretation of Canadian Forces policies relating to expression of

personal opinions, political activities, civil employment, conflict of interest

and post-employment compliance measures, harassment and racist conduct.[765]

11.59

All Board members of the CFGB are civilians, although

some members may have been serving members of the Forces. They are appointed by

the Governor in Council for terms not exceeding four years. The Chairperson is

a full-time member, is the Chief Executive Officer of the Board, and has

supervision over and direction of the work of the Board staff.

11.60

The CFGB has the powers of an administrative tribunal

to summon civilian or military witnesses, as well as order testimony under

oath, and the production of documents. In the interests of individual privacy,

hearings are held in-camera. Nonetheless, the Chairperson may decide to hold

public hearings when it is deemed the public interest is at stake. The Board is

supported in its work by experts in the fields of labour relations, human

resources and the law and is accountable to parliament through annual

reporting.

11.61

In 2003, an independent review found that the CFGB had

been a positive development especially in conveying the perception of

impartiality in the review of grievances. It, however, had not solved the

problem of unnecessary delays. The large number of outstanding grievances was

deemed to be unacceptable and of serious concern. The report recommended that

clear time limits be established for a grievance to proceed through the

process.[766]

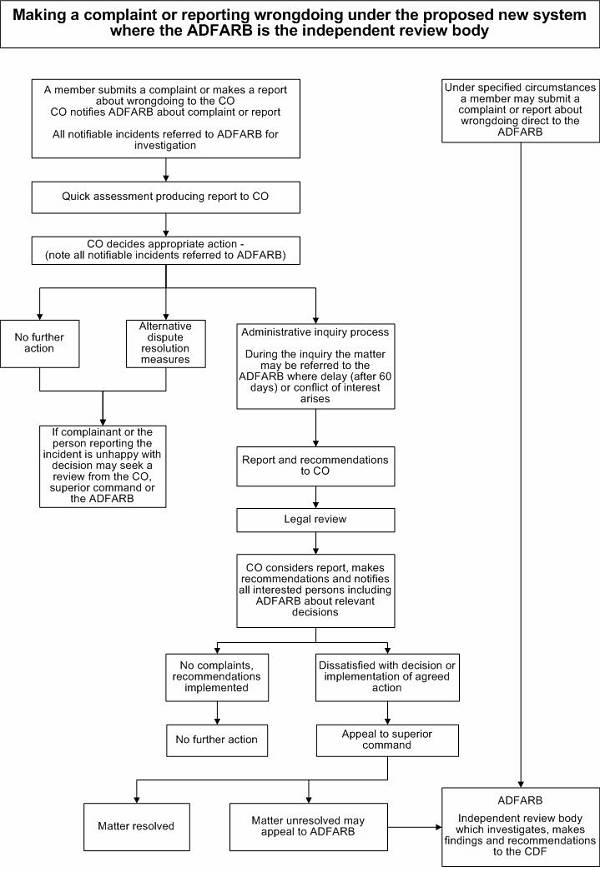

Proposed new Australian Defence Force Administrative Review Board (ADFARB)

11.62

In turning to the Australian military justice system,

the committee found that the perceived lack of independence dominated the

discussion on the administrative system. Concerns about partiality and bias

emerged in the reporting stage of a complaint or report, carried through into

the investigation phase and finally into the internal appeal or review

processes. Without doubt reforms are needed to ensure that the independence of

those investigating complaints or grievances is beyond question.

11.63

The committee understands that the establishment of the

IGADF was intended to address this perception of independence. While the IGADF

is a step in the right direction, the committee believes that it does not go

far enough in establishing an independent review body for grievances. It is of

the view that any further ad hoc change to the system will only exacerbate

problems rather than ameliorate them and prolong the life of a system that is

fundamentally flawed.

11.64

Having said that, the committee commends the

initiatives being taken by the IGADF to establish a database of administrative

inquiries, to improve the training of investigating officers and to develop a

register of investigators. Even so, it is not confident that such measures are

sufficiently strong to eradicate the perception of bias and to engender public

trust in the system. The committee believes that the time has arrived for a

restructure of the system and sees great merit in adopting the CFGB model.

11.65

In the committee's proposed structure, the chain of

command retains the primary responsibility for resolving administrative

complaints or grievances but a statutorily independent body established along

the lines of the Canadian Forces Grievances Board will assume a strong presence

as an appeals body. Mr Michael

Griffin in his paper commissioned by the

committee proposed the established of such a body to be named the Australian

Defence Force Administrative Review Board (ADFARB). He explained:

...it may be best to provide the opportunity for COs

to manage these administrative problems initially and keep the first level of

review within the unit for a reasonable period, the suggested 30 days, before

it is referred to ADFARB. However, the volume of complaints received by the Committee

about the handling of ROG at the unit level and the degree of damage caused

thereby suggests that some external accountability is required. Therefore, it

may be necessary to require notification to ADFARB within 5 working days of the

lodgement of every ROG at unit level, with 30 day progress reports to be

provided to and progress monitored by ADFARB.

The program of training for investigators can be maintained

within Defence with oversight by ADFARB and the panel of suitable investigators

raised by the IGADF can be incorporated into this process (thereby preserving

an asset for use on overseas operations as required). ADFARB can call upon such

investigators as required or conduct its own investigations or formal hearings

if necessary.[767]

11.66

The committee agrees with Mr

Griffin's proposal.

Recommendation 29

11.67 The committee makes the following recommendations—

a) The committee

recommends that:

-

the Government establish an Australian Defence

Force Administrative Review Board (ADFARB);

-

the ADFARB to have a statutory mandate to review

military grievances and to submit its findings and recommendations to the CDF;

-

the ADFARB to have a permanent full-time

independent chairperson appointed by the Governor-General for a fixed term;

-

the chairperson, a senior lawyer with proven

administrative law/policy experience, to be the chief executive officer of the

ADFARB and have supervision over and direction of its work and staff;

-

all ROG and other complaints be referred to the

ADFARB unless resolved at unit level or after 60 days from lodgement;

-

the ADFARB be notified within five days of the

lodgement of an ROG at unit level with 30 days progress reports to be provided

to the ADFARB;

-

the CDF be required to give a written response

to ADFARB findings/recommendations;

-

if the CDF does not act on a finding or

recommendation of the ADFARB, he or she must include the reasons for not having

done so in the decision respecting the disposition of the grievance or

complaint;

-

the ADFARB be required to make an annual report

to Parliament.

b) The committee

recommends that this report

-

contain information that will allow effective

scrutiny of the performance of the ADFARB;

-

provide information on the nature of the

complaints received, the timeliness of their adjudication, and their broader

implications for the military justice system—the Defence Force Ombudsman's

report for the years 2000–01 and 2001–02 provides a suitable model; and

-

comment on the level and training of staff in

the ADFARB and the adequacies of its budget and resources for effectively

performing its functions.

c) The committee

recommends that in drafting legislation to establish the ADFARB, the Government

give close attention to the Canadian National Defence Act and the rules of

procedures governing the Canadian Forces Grievance Board with a view to using

these instruments as a model for the ADFARB. In particular, the committee

recommends that the conflict of interest rules of procedure be adopted. They

would require:

-

a member of the board to immediately notify the

Chairperson, orally or in writing, of any real or potential conflict of

interest, including where the member, apart from any functions as a member, has

or had any personal, financial or professional association with the grievor;

and

-

where the chairperson determines that the Board

member has a real or potential conflict of interest, the Chairperson is to

request the member to withdraw immediately from the proceedings, unless the

parties agree to be heard by the member and the Chairperson permits the member

to continue to participate in the proceedings because the conflict will not

interfere with a fair hearing of the matter.

d) The committee further recommends that to

prevent delays in the grievance process, the ADF impose a deadline of 12 months

on processing a redress of grievance from the date it is initially lodged until

it is finally resolved by the proposed ADFARB. It is to provide reasons for any

delays in its annual report.

e) The committee also recommends that the powers

conferred on the ADFARB be similar to those conferred on the CFGB. In

particular:

-

the power to summon and enforce the attendance

of witnesses and compel them to give oral or written evidence on oath or

affirmation and to produce any documents and things under their control that it

considers necessary to the full investigation and consideration of matters

before it; and

-

although, in the interest of individual privacy,

hearings are held in-camera, the chairperson to have the discretion to decide

to hold public hearings, when it is deemed the public interest so requires.

f) The committee recommends that the

ADFARB take responsibility for and continue the work of the IGADF including:

-

improving the training of investigating

officers;

-

maintaining a register of investigating officers,

and

-

developing a database of administrative

inquiries that registers and tracks grievances including the findings and

recommendations of investigations.

g) To

address a number of problems identified in administrative inquiries at the unit

level—notably conflict of interest and fear of reprisal for reporting a

wrongdoing or giving evidence to an inquiry—the committee recommends that the ADFARB

receive reports and complaints directly from ADF members where:

-

the investigating officer in the chain of

command has a perceived or actual conflict of interest and has not withdrawn

from the investigation;

-

the person making the submission believes that

they, or any other person, may be victimised, discriminated against or

disadvantaged in some way if they make a report through the normal means; or

-

the person has suffered or has been threatened

with adverse action on account of his or her intention to make a report or

complaint or for having made a report or complaint.

h) The committee further recommends that an

independent review into the performance of the ADFARB and the effectiveness of

its role in the military justice system be undertaken within four years of its

establishment.

11.68

The committee understands that, at the moment, there

are a number of complaints and ROGs that still remain unresolved years after

being lodged. It believes that the ADF should take steps immediately deal with

this backlog of grievances.

Recommendation 30

11.69 The committee recommends that the Government provide

funds as a matter of urgency for the establishment of a task force to start

work immediately on finalising grievances that have been outstanding for over

12 months.

11.70

The following chapter examines inquiries that are

concerned with serious and complex matters requiring a higher level of

investigation—the Board of Inquiry.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page