Chapter 2

Background

2.1

The terms of reference of the inquiry are comprehensive. This chapter

provides background to the report and provides an overview of Australia's

retirement income system. This chapter also briefly outlines the gendered gap

in pay, the gap between the accumulated wealth and retirement savings of men

and women, the factors across women's working lives that affect their economic

security in retirement, the economic security of women currently in retirement

and the need for both short and longer term measures to improve the economic

security of women in retirement.

Australia's retirement income system

2.2

Australia's retirement income system is made up of three complementary elements,

or 'pillars':

-

a publicly-funded, means-tested Age Pension;

-

mandatory employer contributions to private superannuation; and

-

voluntary savings—including voluntary superannuation and other

long-term saving through property, shares and managed funds.[1]

Pillar 1—Age Pension

2.3

Introduced in 1909, the Commonwealth Age Pension was originally designed

as a social welfare safety net for those not able to support themselves fully during

retirement. The Age Pension is Australia's largest social security payment,

totalling an estimated $44 billion in 2015–16. The maximum rate of the Age

Pension is $784.80 per fortnight for single persons and $599.10 per fortnight

for each member of a couple.[2]

Generally, the Age Pension is available to men and women aged 65 years and over

who are citizens of Australia and have been permanent residents for at least

10 years, with eligibility subject to means testing in the form of an

income test and an assets test.[3]

Pillar 2—compulsory superannuation

2.4

Superannuation was fairly uncommon in Australia until the 1970s, when it

began to be included in industrial awards.[4]

In 1985, only 39 per cent of the workforce had superannuation—24 per cent of

women and 50 per cent of men had access to super.[5]

At that stage, superannuation coverage was concentrated in higher paid

white-collar positions in large corporations and, in the public sector.[6]

2.5

Superannuation became a major component of Australia's retirement system

following the introduction of the Superannuation Guarantee in 1992. The Superannuation

Guarantee requires employers to contribute a percentage of an employee's

earnings into a superannuation fund, which the employee cannot access until

they reach the superannuation preservation age. For most employees, superannuation

coverage expanded following the introduction of compulsory superannuation. In

1993, 81 per cent of employed Australians were covered by

superannuation and the gender gap in superannuation coverage had narrowed, with

82 per cent of employed men and 78 per cent of employed women covered by

superannuation. The employer contribution rate has increased over time, from 3 per cent

in 1992 to the current rate of 9.5 per cent.[7]

Pillar 3—voluntary savings

2.6

The largest asset for most Australian households is housing followed by

superannuation. Other financial assets such as shares, managed funds and cash

in bank accounts make up a much smaller proportion of household wealth. In an

effort to encourage Australians to make additional savings for their

retirement, governments have implemented a range of incentives, such as the

introduction of the superannuation co-contribution scheme. The upper age limit

for voluntary superannuation contributions has also been increased from 65 to

75 years for older workers, on the condition that they remain attached to

the workforce.[8]

Other factors affecting economic

security in retirement

2.7

Retirement income is not the only factor contributing to economic

security in retirement. Access to affordable housing, health and aged care are

also fundamental to ensuring economic security and allowing people to maintain

their living standards in retirement.[9]

Gender pay gap, gender retirement savings gap, and gender wealth gap

2.8

The gender pay gaps and gender wealth gaps that persist over women's

working lives contribute to the gap in retirement savings and the disparity in

men's and women's economic security in retirement.

Gender pay gap

2.9

A significant contributor to the gender gap in retirement savings is the

gender pay gap. The gender pay gap is the difference between women's and men's

average weekly full-time equivalent earnings, expressed as a percentage of

men's earnings. The gender pay gap was 18.8 per cent in November 2014, and was

17.9 per cent in November 2015. The Workplace Gender Equality Agency

(WGEA) noted that over the past 20 years the gender pay gap has hovered

between 15 and 19 per cent.[10]

2.10

The gender pay gap increases to 23.9 per cent for full-time workers when

taking into account total remuneration, which includes superannuation,

overtime, bonus payments and other discretionary pay. Men working full-time

earn around $17,000 more than women each year in their base salary, but this

extends to $27,000 when assessing total remuneration.[11]

2.11

There are a number of interrelated work, family and societal factors

that influence the gender pay gap. Stereotypes still persist about the type of

work women and men 'should' do, and the way women and men 'should' engage in

the workforce. Factors that contribute to the gender pay gap include:

-

women and men working in different industries (industrial

segregation) and different jobs (occupational segregation). Historically,

female-dominated industries and jobs have attracted lower wages than

male-dominated industries and jobs;

-

a lack of women in senior positions, and a lack of part-time or

flexible senior roles. Women are more likely than men to work part-time or

flexibly because they still undertake most of society’s unpaid caring work and

may find it difficult to access senior roles;

-

women's more precarious attachment to the workforce (largely due

to their unpaid caring responsibilities);

-

differences in education, work experience and seniority; and

-

discrimination, both direct and indirect.[12]

2.12

The gendered disparity in earnings begins when women first enter paid

employment, with female graduates earning less than men, on average. While the gender

pay gap exists across all age groups, the divergence between male and female

earnings increases after women reach 25–34 years of age, which reflects a

reduction in workforce participation by women when they have children.[13]

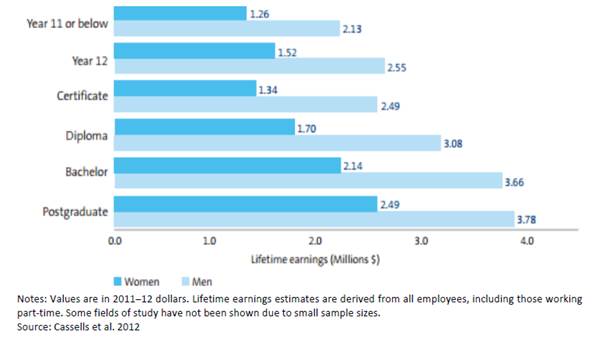

2.13

Gender pay gaps represent a career long penalty for women which is

reflected in prospective lifetime earnings. The figure below shows the gender

gap in prospective lifetime earnings across education groups.[14]

Gender gap in lifetime earnings, million dollars[15]

2.14

Recent research by the WGEA and Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre showed

that:

...if women and men move through managerial positions at the

same pace, working full-time and reaching a KMP [key management personnel] role

in their tenth year, men can expect to earn $2.3 million and women $1.7 million

in base salary over this period—a difference of $600,000. Even in a scenario

where women move towards a KMP role at a rate twice as fast as men their

accumulated earnings would will still be lower than men's—$1.6 million

compared to $1.7 million.[16]

2.15

Based on the 2015 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) Indicators of Gender Equality in Employment data, Australia had

the 24th largest gender pay gap of the 34 OECD countries.

Australia's gender pay gap of 17.9 per cent is above the OECD average

of 15.5 per cent.[17]

Retirement savings gap

2.16

As the Senate noted at the time the inquiry was referred, on average

women retire with approximately half the level of retirement savings of men. In

2011–12, the average superannuation balance at retirement was $105,000 for

women and $197,000 for men, resulting in a gender retirement superannuation gap

of 46.6 per cent.[18]

The committee acknowledges that the average superannuation balance at

retirement for both women and men is low, and measures should be taken to

improve this level.

2.17

The table below shows the disparity between men's and women's

superannuation balances over time across all age groups.[19]

Average

superannuation balances by age, 2011-12

|

Age group

|

Women’s average superannuation

($)

|

Men’s average superannuation

($)

|

Difference

($)

|

Gender superannuation gap

(%)

|

|

20-24

|

$4,403

|

$5,533

|

$1,130

|

20.4

|

|

25-29

|

$13,399

|

$18,899

|

$5,500

|

29.1

|

|

30-34

|

$22,765

|

$32,819

|

$10,054

|

30.6

|

|

35-39

|

$36,142

|

$53,221

|

$17,079

|

32.1

|

|

40-44

|

$43,826

|

$66,503

|

$22,677

|

34.1

|

|

45-49

|

$60,618

|

$102,358

|

$41,740

|

40.8

|

|

50-54

|

$71,661

|

$136,707

|

$65,046

|

47.6

|

|

55-59

|

$91,216

|

$203,909

|

$112,693

|

55.3

|

|

60-64

|

$104,734

|

$197,054

|

$92,320

|

46.9

|

|

65-69

|

$90,185

|

$172,767

|

$82,582

|

47.8

|

|

70-74

|

$65,121

|

$142,790

|

$77,669

|

54.4

|

|

75-79

|

$24,027

|

$55,291

|

$31,264

|

56.5

|

|

80-84

|

$15,536

|

$52,006

|

$36,470

|

70.1

|

|

85+

|

$17,544

|

$35,555

|

$18,011

|

50.7

|

|

Total

|

$44,866

|

$82,615

|

$37,749

|

45.7

|

2.18

The gender gap in retirement savings is the result of a combination of

interrelated factors across the course of a woman's working life. These factors

include:

-

the gender pay gap—men earn more, on average, than women, and as

compulsory employer superannuation contributions are based on a percentage of

income, they will be higher for men than for women;

-

time out of paid employment—women are also more likely to take

time out of paid employment to care for children or other family members and

therefore miss out on employer superannuation contributions; and

-

differences in working hours—women are more likely to work

part-time because of caring responsibilities and therefore earn less and

receive lower levels of employer superannuation contributions.[20]

Gender wealth gap

2.19

The gender wealth gap refers to the difference between men's and women's

accumulation of assets. In 2006, the accumulated wealth of single adult men

was, on average, 14.4 per cent higher than that of single women.[21]

Although female labour market participation has increased, the rate of wealth

accumulation by single women to finance retirement needs has been slower than

that of single men's. The gender wealth gap among single men and women more

than doubled from 10.4 per cent to 22.8 per cent between 2002 and 2010.[22]

2.20

There is also a difference in the composition of women's and men's

wealth. Among single, older women, 60 per cent of their assets and 74 per cent

of their total debt relates to the family home.[23]

In particular, single women hold a higher proportion of their assets in their

home than single men, and divorced women have significantly lower asset

balances than widows.[24]

The composition of wealth held in superannuation for women is 12.4 per

cent compared to 18.8 per cent for men.[25]

2.21

Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre explained:

The factors contributing to the gender wealth gap extend

beyond commonly identified labour market differences between men and women

(such as lower rates of labour force participation and lower wage rates). The

negative effects of single parenthood are particularly severe for women, and

additional barriers to wealth accumulation exist for women from culturally and

linguistically diverse backgrounds and those living in rural areas.[26]

Women's working lives

Industrial and occupational

segregation

2.22

Historically, female-dominated industries and jobs have attracted lower

wages than male-dominated industries and jobs. This is evident early in women's

working lives in the gender pay gap for graduates.

2.23

Although women outnumber men graduating from higher education, the starting

salaries for male graduates are higher than for women:

-

female graduate salaries are 95 per cent of male graduate

salaries (a difference of $2,000 per annum); and

-

female postgraduate salaries are only 82 per cent of male postgraduate

salaries (or $15,000 per annum).[27]

2.24

This gap in graduate and postgraduate salaries is in part due to fewer

women working in higher paid occupations such as science and engineering. Instead,

women are more likely to be employed in lower paid occupations. For example:

-

women make up 60–70 per cent of workers in three lower paid

occupations—clerical and administration, community and personal services and

sales; and

-

women make up 60–80 per cent of workers in lower paid health, social

assistance, education and training industries.[28]

Career breaks, unpaid care and

workforce participation

2.25

The female workforce participation rate in 2013–14 was 65 per cent,

compared to 78.4 per cent for men. Women were more likely to be employed

part-time, with 43.4 per cent of employed females aged 20–74 years employed

part-time compared to 14.4 per cent of employed males in the same age group.[29]

2.26

The Australian Human Rights Commission's Investing in care:

Recognising and valuing those who care report observed that the current

superannuation system, which is tied to paid work, results in inequitable

outcomes and savings for women who are, or have been, unpaid carers.[30]

It found:

-

Women are more likely than men to provide unpaid caring work;

-

Women made up the majority of carers, representing 70 per cent of

primary carers and 56 per cent of carers overall;

-

Women comprised 92 per cent of primary carers for children with

disabilities, 70 per cent of primary carers for parents and 52 per cent of

primary carers for partners. While 57.5 per cent of mothers whose youngest

child is aged

0–5 years were participating in the labour force, 94 per cent of fathers,

whose youngest child is 0–5 years, were working or looking for work; and

-

63 per cent of employed female parents are employed in part-time

work, compared to 7 per cent of employed male parents.[31]

2.27

In its earlier 2009 report Accumulating poverty? Women's experiences

of inequality over the lifecycle, the Australian Human Rights Commission

noted that the limited availability of flexible work arrangements and quality

affordable childcare present a barrier for women's participation in the paid

workforce and, subsequently, the accumulation of retirement savings in

superannuation.[32]

Women in leadership

2.28

The 2015 ANZ Women's Report: Barriers to achieving gender equity

observed that although women in Australia are better educated and have more

employment opportunities than ever before, they remain under-represented in

senior leadership roles in both the corporate and public sectors:

-

women make up 20.4 per cent of ASX 200 board positions;

-

women represent 17.3 per cent of CEOs, 26.1 per cent of key

management personnel, 27.8 per cent of other executives/general managers, 31.7

per cent of senior managers and 39.8 per cent of other managers; and

-

women represent 31 per cent of all federal, state and territory

parliamentarians.[33]

2.29

The factors contributing to low female representation in senior

leadership positions include unconscious bias in the workplace, and a lack of

flexibility in senior management roles.[34]

The WGEA noted that only 6.3 per cent of managerial roles are offered on a part-time

basis.[35]

Women approaching retirement

2.30

As access to superannuation was limited prior to 1992, many women

currently approaching retirement have only had access to the superannuation

system for part of their working life. In addition, the rate of the

Superannuation Guarantee, which only increased gradually from 3 per cent in

1992 to 9 per cent in 2002, and did not again increase until 2013, has been

insufficient to result in adequate superannuation savings.[36]

Women in Super noted:

Even for women coming up to retirement the picture is not

good. The median superannuation account balance for a women aged 55–64 years is

$80,000 (for a man in the same age group it is $150,000) and 1 in 3 women

currently live alone between the ages of 55–70 years. Many females will need to

work longer than their male colleagues in order to save more for retirement.

Reasons for this include the gender pay gap, career breaks and not being

allowed to participate in earlier schemes due to their sex and prevailing

belief that their husbands would provide for them.[37]

Women in retirement

2.31

Women are at greater risk of experiencing poverty in retirement.[38]

Older single women are one of the fastest growing cohorts of people living in

poverty.[39]

According to the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA)

Survey, in 2012, 38.7 per cent of older single females were living in poverty.[40]

2.32

As women currently accumulate significantly less savings for their

retirement, women account for over half those receiving the Age Pension, and

single women are most likely to be solely reliant on the full Age Pension for

income.[41]

The Australian Human Rights Commission provided the following statistics:

In 2011, women comprised 56.5 per cent of the 2.23 million

recipients of the age pension. Just over half (53.6 percent) of female age

pension recipients were single and 71.8 percent of single age pension

recipients are women. Sixty-one percent of female age pensioners received the

maximum rate, and 27.3 percent were not home owners.[42]

2.33

Women have a higher life expectancy than men which exacerbates the

effect of the retirement savings gap. Women are also more likely to re-enter

the workforce after retirement due to financial constraints, and are twice as

likely as men to sell their house and move to lower cost accommodation due to

financial circumstances in retirement.[43]

2.34

It cannot be assumed that women will be able to rely on a male partner's

savings for financial support in retirement, as one third of women are not in relationships

by retirement age, and 40 per cent of couples will not have sufficient savings

to cover the gap in women's superannuation.[44]

As one submission observed, 'a husband isn't a superannuation plan'.[45]

2.35

Research by the Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) found that

retirees often coped with the change in their financial circumstances in

retirement by cutting back on normal weekly spending. It noted that this was

more common for women, particularly single women, with 30 per cent reporting they

had cut down on weekly spending, compared to 21 per cent of partnered women.[46]

2.36

Dr Debra Parkinson, Women's Health in the North, explained that many

women involved in the Living Longer on Less research project were going

without in retirement. She stated:

The women we spoke to said they could not afford power. Their

strategies were to sit with a hot water bottle and a blanket at night, and they

would light candles rather than turn on the power. Our connections with the

Metropolitan Fire Brigade say that they know about this. There are fires that

should not be happening because people are saving money on power. They try to

save on food by rarely eating meat or fish or by no longer having three meals a

day. One ate just fruit and vegetables all week, and she would shop on a

Saturday, just before the markets closed, to get the old fruit and vegetables.

A couple of women said they had not had a professional haircut for a decade.

Some had no money for even a $4 cup of coffee, which meant they could not

socialise—they were too embarrassed that they could not pay for a cup of

coffee.[47]

Need for long and short term approaches

2.37

Many submissions and witnesses highlighted the need for long and short

term approaches to address the need to improve women's economic security in

retirement. The Age and Disability Discrimination Commissioner, the Hon Susan

Ryan AO, expressed concern that most of the underlying causes of the

gender gap in retirement savings will require a lot of work and are unlikely to

be resolved in the near future. She stated:

I am concerned not only for the women who are now approaching

retirement—say, women in their 60s or late 50s—who in general will not have

adequate retirement savings and may, in some circumstances, be facing an old

age of poverty, but also younger women who, because of these entrenched

inequalities in pay, caring responsibilities and so on, will, as we go forward,

still be facing poverty in retirement. So I think it is important to look at

immediate changes that could be made as well as those that could be made in the

longer term.[48]

2.38

The AIFS also noted the need for longer and shorter term approaches to

addressing women's economic security in retirement:

...the current situation in which the majority of retirees are

reliant on the age pension as their main source of retirement income; and

single women are the least likely to be able to afford even a modest lifestyle

in retirement. Changes to superannuation policy to address the issue of the

gender gap in superannuation savings, along with policies that encourage the

increased labour force participation of women, may assist retirees in decades

to come. However, for the current cohort of retirees, these changes will have

no effect on their standard of living. For those who are already in retirement,

policy reform targeting assistance to those in genuine financial hardship is

the only type of reform that will bring real improvements to living standards.[49]

2.39

This chapter has provided a brief overview of the retirement income

system, and the various factors that contribute to women's economic security in

retirement, highlighting the need for a multifaceted approach incorporating

both long and short term measures to improve retirement outcomes for women.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page