Chapter 6

Out-of-home care models and supports

There is a particular onus on us, as an Australian society

when we have taken over responsibility for that child...it is important to make

sure that we take that responsibility for fewer children because we have

invested a lot more a lot earlier to prevent that large number—an increasingly

large number—coming into the care and responsibility of the State but, when we

do, it then becomes absolutely imperative that we provide the best quality

care, which really is dependent on having the best supports for those carers.[1]

Dr Daryl Higgins, Melbourne hearing, 20 March 2015

6.1

This chapter examines the following terms of reference:

(c) current models for out of home care, including kinship

care, foster care and residential care;

(e) consistency of approach to out of home care around

Australia;

(f) what are the supports available for relative/kinship

care, foster care and residential care; and

(g) best practice in out of home care in Australia and internationally.

6.2

As discussed in Chapter 4, children and young people in out-of-home care

have a range of complex needs, requiring a greater level of support. The

committee heard that across jurisdictions, the existing models of care do not consistently

support these needs.

6.3

This chapter assesses models of delivery and support for the three main

forms of care (foster, relative/kinship and residential care) across

jurisdictions and makes suggestions for changes based on best practice

examples. It assesses specific issues for each type of care, as well as cross

jurisdictional issues that affect all care types.

6.4

Specific models of care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

children will be examined in Chapter 8. Specific models of care for children

with disability and other groups will be examined in Chapter 9.

Types of care

Numbers of children and young

people

6.5

As noted in Chapter 1, the three main types of out-of-home care are

relative/kinship care, foster care and residential care. In 2012-13, these

three types of care accounted for around 96 per cent of children and young

people in out-of-home care. Most children were in relative/kinship (47.9 per

cent) and foster care (42.6 per cent) placements, with a significantly smaller

proportion in residential care (5.5 per cent).[2]

Table 6.1 shows the breakdown of children and young people by type of care at

30 June 2013. Table 6.2 shows the proportion of children in the three main

types of care across jurisdictions at 30 June 2013.

Table 6.1 – Children in out-of-home care, by type of placement, states and

territories, 30 June 2013

|

Type of placement

|

NSW

|

Vic

|

Qld

|

WA

|

SA

|

Tas

|

ACT

|

NT

|

Total

|

|

Foster

care

|

7,091

|

2,069

|

4,492

|

1,465

|

1,102

|

445

|

209

|

399

|

17,272

|

|

Relative/kin

|

9,730

|

3,248

|

3,026

|

1,619

|

1,190

|

303

|

291

|

19*

|

19,426

|

|

Other

home-based care

|

0

|

695

|

0

|

0

|

6

|

235**

|

20

|

202

|

1,158

|

|

Total home-based care

|

16,821

|

6,012

|

7,518

|

3,084

|

2,298

|

983

|

520

|

620

|

37,856

|

|

Family

group homes

|

19

|

0

|

0

|

191

|

N/A

|

22

|

0

|

4

|

236

|

|

Residential

care

|

480

|

495

|

618

|

150

|

330

|

25

|

38

|

75

|

2,211

|

|

Independent

living

|

93

|

33

|

0

|

0

|

29

|

5

|

|

2

|

162

|

|

Unknown

|

9

|

2

|

0

|

0

|

N/A

|

32

|

0

|

41

|

84

|

|

Total

|

17,422

|

6,542

|

8,136

|

3,425

|

2,657

|

1,067

|

558

|

742

|

40,549

|

* In the NT's client information system, the majority

of children in a relative/kinship placement are captured in the foster care

placement type.

** In Tasmania, children under

third party guardianship orders are counted under 'other-home based care'.

Source: AIHW, Submission

22, Table 6.

Table 6.2 – Proportion of children in main types of care, 30 June 2013

|

|

NSW

|

Vic

|

Qld

|

WA

|

SA

|

Tas

|

ACT

|

NT

|

Total

|

|

Foster care

|

40.7

|

31.6

|

55.2

|

42.8

|

41.5

|

41.7

|

37.5

|

53.8

|

42.6

|

|

Relative/kin

|

55.8

|

49.6

|

37.2

|

47.3

|

44.8

|

28.4

|

52.2

|

2.6*

|

47.9

|

|

Residential care

|

2.8

|

7.6

|

7.6

|

4.4

|

12.4

|

2.3

|

6.8

|

10.1

|

5.5

|

|

Other

|

0.7

|

11.2

|

0.0

|

5.5

|

1.3

|

27.6

|

3.5

|

33.5

|

4.0

|

* In the NT's client

information system, the majority of children in a relative/kinship placement

are captured in the foster care placement type.

Source: AIHW, Submission 22,

Table 6.

Funding for types of out-of-home

care

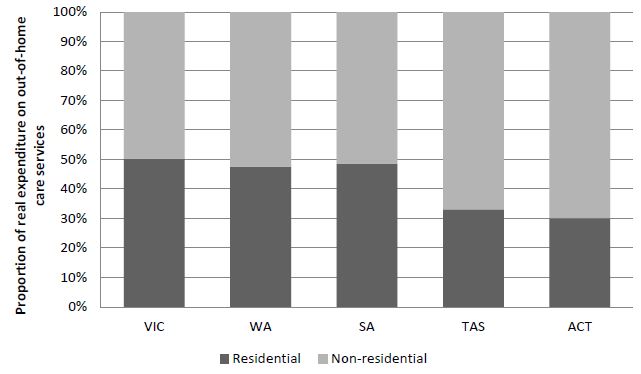

6.6

Despite residential care placements accounting for just 5.5 per cent of

children in care nationally, in some jurisdictions, expenditure on residential

care accounts for over half of all expenditure on out‑of‑home care

services.[3]

6.7

Data collected by the Productivity Commission on annual real expenditure

by type of care (available for Victoria, WA, SA, Tasmania and the ACT only) indicates

that expenditure on residential care is significantly higher than

non-residential care (relative/kinship care and foster care). Figure 6.1 shows

the proportion of spending on residential and non-residential out-of-home care

across jurisdictions for 2013–14.

Figure 6.1 – Proportion of real expenditure on residential and

non-residential care, 2013/14

Source:

Productivity Commission, Report on Government Services, Table 15A.3.

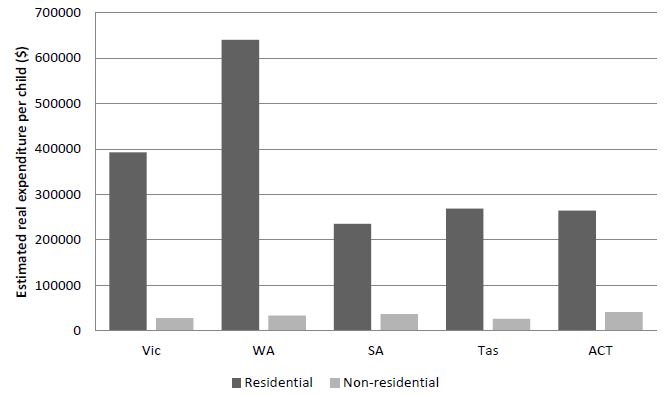

6.8

States and territories spend a significantly higher amount per child on

residential care than non-residential care. Across jurisdictions, estimated

real expenditure per child for residential care is between 6 and 19 times

higher than non‑residential care.[4]

Figure 6.2 shows the estimated real expenditure per child for residential and

non-residential care across jurisdictions for 2013–14.[5]

Figure 6.2 – Estimated real expenditure per child for residential and

non-residential out-of-home care services, 2013/14

Source: Productivity

Commission, Report on Government Services, Table 15A.3.

Relative/kinship care

6.9

As discussed in Chapter 4, relative/kinship care has the potential to

provide greater stability and more positive long-term outcomes for children and

young people than other forms of care.[6]

6.10

All jurisdictions support statutory relative/kinship care as the

preferred form of care for children and young people. As

noted in Table 6.2, in most jurisdictions children are placed in relative/kinship

care more than any other type of care.[7]

Relative/kinship care is the preferred option for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander children, consistent with the Aboriginal Child Placement Principle.[8]

6.11

The committee notes that many of the issues experienced by

relative/kinship carers discussed below were also identified in the committee's

2014 inquiry, Grandparents who take primary responsibility for raising their

grandchildren.[9]

Support for relative/kinship care

placements

6.12

The committee heard that relative/kinship carers are more likely to be

disadvantaged than other types of carers.[10] A report by the Social

Justice Social Change Research Centre found that relative/kinship carers were

predominantly female, older, more likely to have lower incomes, to be in public

rental accommodation, less likely to be employed, or to have a university

qualification than foster carers.[11] Relative/kinship carers

were more likely to have an income from a Centrelink pension or benefit with a

gross weekly income between $80 and $1 000. One third of the relative/kinship

carers had a weekly income of less than $500.[12]

6.13

Dr Marilyn McHugh, a research fellow from the University of New South

Wales, found that compared to foster carers, relative/kinship carers:

...are usually older,

in poorer health, on lower incomes, and more reliant on income support

payments...are less likely to be employed or have university degrees or to

receive training, case planning or supervision. Indigenous kinship carers are

particularly vulnerable: most in strained financial circumstances have

generally high levels of material disadvantage, including poor or inadequate

housing. Many have sibling groups in their care.[13]

6.14

Berry Street, an out-of-home care service provider in Victoria, also

highlighted that the often complicated relationship between relative/kinship

carers and the parents of children can add stress and complexity compared with other

types of care:

...kinship carers have

a very different relationship with the birth parents – family relationships can

be fraught, contributing to stress and mental health problems. In some cases

kinship carers may be ill equipped for their role due to a range of complex

factors. These vulnerabilities can pose additional risk for the children and young

people in care.[14]

6.15

The committee heard that the current model of relative/kinship care do

not adequately support carers to meet the increasingly complex needs of

children entering care. Berry Street noted submitted that the:

...current approach to kinship care and level of resourcing

does not adequately recognise or acknowledge that the kinship clients

essentially have similar profiles and needs to those of other clients of the

home based care system.[15]

6.16

A large number of submitters and witnesses called for increased

financial and practical supports for relative/kinship care across

jurisdictions, including increases to reimbursements and allowances and access

to training, case workers and support groups.[16] The Commission for Children and Young People Victoria (CCYPV)

submitted that relative/kinship care is the fastest growing form of out-of-home

care placement, but that 'the development of a considered and robust model of

kinship care has not kept pace with the growing demand'.[17]

6.17

In particular, submitters highlighted the need for increased supports

for informal relative/kinship carers that do not receive any support from

statutory child protection authorities. Ms Meredith Kiraly noted the need for

ongoing support 'is critical to the wellbeing of children and carers in both

statutory and informal kinship care'.[18]

6.18

A recent study into kinship care by the Benevolent Society, in

partnership with the Social Policy and Research Centre (SPRC) and the

Aboriginal Child, Safety, Family and Community Care State

Secretariat (AbSec), found that kinship carers lack adequate support and

appropriate, accessible services for them and their children, including

counselling, medical, educational and financial or case worker support. The

study highlighted the need for a well-resourced practice framework to support relative/kinship

carers and their families.[19]

Specialist support for

relative/kinship care placements

6.19

The committee heard that specialist support services for

relative/kinship carers and children in relative/kinship care placements are

limited. Across most jurisdictions, relative/kinship care placements are

approved and supervised by government.[20]

Unlike foster care, where community service organisations (CSOs) are funded to

provide case management support to carers, relative/kinship carers rely on

government departments for ongoing support, including allocation of

caseworkers.[21]

6.20

The committee heard that ongoing support for carers is limited due to

resourcing constraints, and in some cases, carers are not allocated caseworkers

to provide additional support:

...many of these children’s cases sit on a list of

‘unallocated’ cases. Where cases are allocated, workloads only allow for a

minimum level of casework driven by urgent need.[22]

6.21

Witnesses expressed concerns about the impact of the lack of ongoing

support provided to relative/kinship carers. Mr Julian Pocock, Director of

Public Policy at Berry Street, told the committee at its Melbourne hearing:

...it is not tolerable for the system in Victoria and elsewhere

to proceed on a basis where we have some children and young people in

placements which are subject to external monitoring and scrutiny and where

external auditors come in and ask questions and review files and see what is

happening to kids; and we have another part of the system—and in Victoria it is

half of the system now—still run by the department in kinship care, which is

not subjected to any external monitoring or any standards—no-one comes in to

review what is happening to those kids. From the perspective of the child, it

should not be a lottery as to whether or not you end up in the placement that

has some benefit of external monitoring or a placement that does not.[23]

6.22

In some jurisdictions, organisations are funded to provide some support

to relative/kinship placements. However, this differs across jurisdictions and

depends on the capacity of the organisations to deliver services. The committee

heard that the Victorian government funds 25 CSOs to provide Kinship Care

Support Programs to approximately 750 children (around 25 per cent of children

in relative/kinship care placements). The remaining children are managed by

government child protection authorities.[24]

6.23

The committee heard that the implementation of supported relative/kinship

care programs across jurisdictions is inconsistent. In the committee's view,

specialist relative/kinship care organisations, such as the Mirabel Foundation

in Victoria, may provide a good example of supported relative/kinship care

placements (see Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 – Best practice – Mirabel Foundation – Kinship carer support

The Mirabel Foundation (Mirabel) was established in Victoria in 1998 to assist children living in

kinship care arrangements due to parental drug use. Mirabel stated that it is currently supporting

more than 1300 disadvantaged children throughout Victoria and New South Wales. More than 65

per cent of these children are placed in statutory out-of-home care kinship placements, with the

remainder placed informally.

Mirabel noted it was established to fill a gap in services available to kinship carers and their children

and has developed a series of programs in response to growing need and a body of tailored research.

The programs Mirabel has identified as most needed and beneficial to kinship families include:

- Assessment of needs and referral to specialist services

- Telephone counselling and support

- Crisis support and assistance

- Kinship carer support groups and therapeutic children’s groups

- Recreation program

- Educational support

- Individual child/youth support

- Children and family events and camps

- Respite care and family holidays

- Youth ambassador outings

- Advocacy

Source: Mirabel Foundation, Submission

36, p. 4.

6.24

The committee heard that there are few best practice models for

supported relative/kinship care in Australia or internationally. Professor

Cathy Humphreys and Ms Meredith Kiraly from the Department of Social Work at

the University of Melbourne submitted that:

dedicated kinship care support programs are in their infancy

everywhere, as is the exchange of information about policy and practice. No

Western country has yet developed a coherent model of protective kinship care

and associated support services. Many jurisdictions regard kinship care as a

form of foster care that can operate more independently. This leads to

difficulty in appreciating the need of children and carers for casework and

other support and also in establishing appropriate standards of carer

assessment, supervision and monitoring.[25]

6.25

Professor Humphreys and Ms Kiraly recommend further research be

undertaken to:

...develop a model of statutory kinship care using local and

international knowledge that may underpin the development of policy and

practice to support children in kinship care, their carers and their parents.[26]

Financial support

6.26

The committee heard that in some jurisdictions, relative/kinship carers

receive lower rates of financial reimbursement than foster carers. Evidence

suggested that although relative/kinship carers are eligible for the same carer

allowances as foster carers, in practice, relative/kinship carers do not

receive the higher allowances available for complex placements.[27]

6.27

In Western Australia, Ms Judith Wilkinson from Key Assets stated that children

in relative/kinship care placements have a range of complex needs:

Kinship carers look after children right across the

spectrum—that is, from what might be called 'low needs', although there really

are no low-needs children who come into care, to extremely high-needs children

who, if they were not in kinship care, might be looked after by specialised

fostering services or residential care.[28]

6.28

A 2014 report into kinship care in Victoria by Baptcare found that the

complexity of kinship placements is often not acknowledged.[29]

Baptcare suggested that 'the current funding model, based on the presumption

that most placements only require low level of support, is inadequate to meet

the needs of these kinship care families'[30]

and recommended that:

...the kinship program model be reviewed, accompanied by a

better funding structure and allocation of resources so that children placed in

kinship care receive equitable care compared to children in other out of home

care programs.[31]

6.29

The CCYPV noted in its submission that in Victoria, relative/kinship

carers are only reimbursed more than the 'general base rate' (between $7 000

and $11 000 per year) in exceptional circumstances.[32]

The CCYPV noted the difference between caregiver reimbursements for relative/kinship

carers and foster carers could be as much as $25 000 (based on the difference

between the base rate for relative/kinship carers of $11 454 per year

compared to the complex placement rate for foster carers of $36 187). The CCYP submitted

that:

the financial burden to kinship carers are under is not

reasonable, viable or sustainable. At present kinship carers receive less than

the base rate for foster carers – it is an inequitable system and ultimately,

the children miss out.[33]

Assessment process

6.30

Relative/kinship carers are required to be assessed by child protection

authorities, including police, criminal, child protection and working with

children background checks. In some cases, this is similar to the assessment

process for foster carers, but with some flexibility. For example, in

Queensland, the assessment process for relative/kinship carers is 'less

structured due to the family connection that already exists between the relative/kinship

carer applicant, the child and the child's parents'.[34]

6.31

However, owing to resourcing constraints, relative/kinship carers may not

be fully assessed for suitability prior to being placed with a child.[35]

In some cases, children may remain in placements with carers who have not been

assessed:

[O]ften it is a police check that is done and that is it.

There is a pre-assessment that is supposed to be done within two weeks.

Pressures on protective workers often mean that that spins out for a number of

weeks, and the proper assessment that is supposed to be done within eight weeks

often spins out for many months.[36]

6.32

Once a child enters a relative/kinship placement, resourcing pressures

mean that the child is unlikely to be moved, regardless of whether it is the

most appropriate placement:

By the time the child has been in placement for weeks or

months, systemic factors bias the assessment towards ratification of the status

quo unless it is patently dangerous to the child. Among these are reluctance to

disrupt the existing care arrangement, and frequently, a lack of alternative

care options.[37]

6.33

As discussed in Chapter 4, the pressure to put 'bums in beds' may result

in children being placed in unsuitable placements. Ms Kiraly noted that the

lack of assessment for relative/kinship carers created a double standard

compared with foster carers:

I do think if the state mandates a placement as out-of-home

care, then we are saying it is a safe place and providing a care allowance is

also indicating that we would not dream of placing a child with a foster carer

without them being fully assessed.[38]

Training support

6.34

The committee heard that relative/kinship carers have limited access to

training and ongoing support, especially compared with foster care.[39]

The Benevolent Society's study found relative/kinship carers receive much less

training than foster carers, with the majority saying that they hadn’t received

any training.[40]

6.35

Across most jurisdictions, there was no mandatory relative/kinship

training. Although carers had access to voluntary training, many courses were not

specific to relative/kinship carers. Table 6.4 outlines the key differences

between training and ongoing support for relative/kinship carers and foster

carers across jurisdictions.

Table 6.3 – Ongoing training support for relative/kinship carers

|

Jurisdiction

|

Relative/kinship care

|

Foster care

|

|

NSW

|

Mandatory course must be

completed within three months

Voluntary relative/kinship

specialist training

|

Mandatory training

|

|

Victoria

|

Voluntary relative/kinship

specialist training

|

Mandatory pre-service training

Specialist training as

required

|

|

Queensland

|

Voluntary

No specific relative/kinship

training

|

Mandatory pre-service and

in-service training

|

|

WA

|

Voluntary

No specific relative/kinship

training

|

Mandatory 'Fostering with

Skill and Care' course (workbook and 19 hours of workshops)

|

|

SA

|

Mandatory courses (Infant Care

and Child Safe Environment)

Voluntary

No specific relative/kinship

training

|

Mandatory training

|

|

Tasmania

|

Voluntary

No specific relative/kinship

training

|

Mandatory (non-legislated)

training

|

|

Northern Territory

|

Mandatory course (six modules)

Voluntary abuse and abuse

prevention training

|

Mandatory course (six modules)

Voluntary abuse and abuse

prevention training

|

Source: State and

territory governments, answers to questions on notice, 30 April 2015 (received

May-June 2015).

6.36

The committee heard that a small number of jurisdictions offer

specialist relative/kinship care training. For example, the Victorian Government

funds support sessions for relative/kinship carers, which are delivered by the

Australian Childhood Trauma Group, Anglicare Victoria and Berry Street. This

training aims to assist carers to understand and manage complex behaviours and

issues using a trauma-informed approach. Victoria also launched culturally

appropriate training for relative/kinship carers of Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander children and professionals in 2014-15.[41]

Peak body

6.37

There is no national peak body for relative/kinship carers to advocate

and work with government. In other jurisdictions, peak bodies represent both

relative/kinship carers and foster carers. NSW advised ongoing support for

foster carer and relative/kinship carers is provided through two peak carer

organisations: Connecting Carers NSW (CCNSW) and Aboriginal State-wide Foster

Carer Support Service (ASFCSS). Both CCNSW and ASFCSS are funded to provide

advice, information and support.[42]

6.38

Some jurisdictions have specific peak bodies for relative/kinship

carers, for example the Kinship Carers Victoria, established in 2010 as an

extension of Grandparents Victoria (see Box 6.2).[43]

Box 6.2 – Best practice – Kinship Carers Victoria

The Victorian Department of Human Services (DHS) funds Kinship Carers Victoria (KCV), the

peak body for kinship carers.

KCV’s aim is to have kinship carers in Victoria supported in their role according to their needs and

the needs of the children they care for. KCV's roles include:

- identify, promote and represent the views of kinship carers in decision making processes;

- inform carers to enable them to better perform their role as carers;

- advocate the needs of kinship carers with decision makers; and

- promote and assist in the delivery of programs designed to support kinship carers.

KCV received funding from DHS to develop a Kinship Carers Handbook which has been used as a

support guide for kinship carers, including grandparents, to provide them with information on a

range of areas including financial assistance, legal matters, cultural connections, health and wellbeing

and education and learning.

Source: Victorian Government,

answers to questions on notice, 30 April 2015 (received 22 May 2015); Kinship

Carers Victoria, http://kinshipcarersvictoria.org/ (accessed 25 May 2015).

6.39

The committee heard there are a number of support organisations across

jurisdictions that provide assistance to relative/kinship carers. However,

funding to these bodies differs across jurisdictions, creating uncertainty and

inconsistency.[44]

Professor Humphreys and Ms Kiraly from the University of Melbourne recommended

Commonwealth funding be allocated:

for a national peak body for kinship care in Australia that

has sufficient resources to collect relevant data, commission research,

advocate for appropriate services for kinship carers and children in their

care, and coordinate State and Territory kinship care peak bodies as they are

established.[45]

Committee view

6.40

The committee notes that evidence received by the committee concerning

the lack of financial and practical support for relative/kinship care supports the

findings of the committee's previous inquiry into grandparent carers.

6.41

The committee acknowledges that relative/kinship carers are assuming

greater responsibility for an increasing number of children who have increasingly

complex needs in statutory out-of-home care. As discussed in Chapter 4, the

committee acknowledges the benefits for the wellbeing of children and young

people in being placed with and connected to their families.

6.42

The committee is concerned statutory and informal relative/kinship

carers are not able to access the same financial and practical supports

(including training and case workers) as foster carers. In particular, the

committee is concerned that the complex needs of children in relative/kinship care

are not recognised, meaning relative/kinship carers are not able to access

higher rates of financial allowances.

6.43

The committee notes the lack of supported kinship care placement models

across jurisdictions for statutory and informal carers. Models provided by some

service providers, such as the Mirabel Foundation, which attempt to improve the

level of support for children in relative/kinship placements were of particular

interest to the committee.

6.44

The committee supports increasing the capacity of emergency respite

services to allow child protection authorities to properly assess

relative/kinship carers prior to placement, rather than placing 'bums in beds'.

This would help to improve safety and stability for children and facilitate

more positive outcomes.

6.45

The committee also supports the establishment of a national peak body to

represent statutory and informal relative/kinship carers across jurisdictions,

including individual and collective advocacy. The committee consider the

establishment of a national peak body would benefit children and carers in

relative/kinship placements.

Foster care

6.46

The committee heard there are significant issues with Australia's

volunteer based model of foster care. Berry Street and the University of New

South Wales argued that foster care in Australia is in a 'state of crisis' due

to out-dated policies and practices, inadequate resources, difficulties in

preventing rapid staff turnover, and difficulties in recruiting and retaining

volunteer foster parents.[46]

Recruitment and retention

6.47

Submitters and witnesses argued that there are significant challenges in

recruiting and retaining appropriately skilled volunteer foster carers across

jurisdictions, particularly for specialist foster care services.[47]

6.48

In 2013–14, AIHW reported that across most jurisdictions (except WA and

the NT), more households exited foster care than commenced foster care,

highlighting that the attraction and retention of appropriately skilled foster

carers is a high priority across Australia.[48]

6.49

The Foster Care Association of Victoria submitted that in Victoria,

there has been a significant increase in non-active carers (approved carers not

actively caring for children), indicating that experienced foster carers may be

choosing not to provide foster care placements.[49]

Financial support

6.50

It was put to the committee that a key reason for the difficulties in recruiting

and retaining appropriately skilled foster carers is the inadequate level of

financial support. Mr Bernie Geary, the Victorian Commissioner for Children

and Young People, told the committee that the issue of foster carer allowances

had been discussed over a long period:

[T]en years ago when I first came into the job as child safety

commissioner I talked to the bureaucrats about what was happening with foster

care, why was it diminishing? It is diminishing because foster carers are

saying to me 'I would be a foster carer but I can't afford it.'[50]

6.51

The committee heard that foster care allowances have been in decline for

some time across jurisdictions. Dr Marilyn McHugh from the Social Policy

Research Centre (SPRC) at the University of New South Wales highlighted that across

jurisdictions, the weekly subsidy for parents is generally less than the cost

of caring for a child. This assessment is based on estimates of the cost of

caring for a child developed by the SPRC, known as the foster care estimate

(FCE).[51]

6.52

Mr Andrew McCallum, CEO of the Association of Children's Welfare

Agencies, argued that foster carers should be paid commensurate to the support

they provide:

A major issue associated with this is that we are still

expecting volunteers in many cases to do some of the most difficult work within

the system...So there is an issue around how we resource a system that is built

around known therapeutic care models for out-of-home care, foster care,

residential care and so forth that will mean more resources for fewer kids,

because we would hope to build a system that would not be driving itself. At

the moment we have a system that is self-perpetuating.[52]

6.53

Similarly, Ms Judith Wilkinson, Chair of the Children's Youth and

Families Agency Association in WA, told the committee of the importance of

providing incentives for volunteer carers:

There is a lot to be said—and foster carers will say this

themselves—for maintaining volunteer carers, but they have to be properly

supported financially, and there has to be an element of reward in the

allowance they get which does not then attract the attention of the ATO in

terms of paying tax on that element.[53]

6.54

A number of submitters and witnesses, including the Foster Care

Associations of Victoria and Tasmania, recommended increasing the subsidies

available to foster carers to cover the actual cost of supporting children in

foster care, taking into account education, medical, allied health and

recreational expenses.[54]

In addition to increased subsidies, these witnesses suggested the Commonwealth

government provide tax exemptions and incentives to foster carers. Mr Geary

also told the committee that tax incentives were needed:

[I]t belies good sense to think that we do not properly

support our foster carers. Give them a break. If that is a tax break, if that

is what is needed, give it to them.[55]

6.55

For example, in the UK, foster parents receiving a Foster Parent Fee are

regarded as self-employed for tax purposes and carers earning up to a maximum

of £10 000 (AUD $15 365) plus allowances, do not pay tax on their income from

fostering.[56]

6.56

The Foster Care Associations of Victoria and Tasmania also suggested

improved access to 'ongoing training, practical support and regular respite for

carers',[57]

as well as funding for individual and collective support and advocacy.[58]

6.57

The committee heard that the volunteer model of foster care does not

attract the highly skilled carers required to address the complex needs of

children and young people. Ms Anita Pell from Berry Street told the committee:

The children are more challenging, the families that they

come from are more complex and our system is much more complex than it was. The

carers that we are trying to recruit are a very different profile of carer that

we need.[59]

6.58

The differences in foster care allowance rates across jurisdictions will

be discussed in more detail below.

Professional foster care

6.59

To address the challenges in recruiting, supporting and retaining foster

carers and addressing the complex needs of children in care, a number of submitters

and witnesses recommended introducing a model of professional foster care.[60]

The Child and Family Welfare Association of Australia submitted that:

...foster care is an increasingly difficult model to sustain as

many children’s needs can only be met by having a full-time at home carer and

the voluntary nature of the work precludes sufficient income being available.[61]

6.60

One of the key advantages to a professional foster care model would be

to provide a home-based care option for children and young people with complex

needs who would otherwise be admitted to residential care. According to

MacKillop Family Services, 'professional foster care has the potential to fill

a gap between foster care provided by volunteers and residential care'.[62]

6.61

Support for the implementation of a professional foster care model

included reforms at the Commonwealth level to taxation and industrial law.[63]

Anglicare Victoria argued that current taxation and industrial policy:

...works against the employment of a full time professional to

allow the employment of a professionalised ‘in-home care’ service option for

children and young people as an alternative to residential care when volunteer

foster care placements are not available.[64]

6.62

The removal of barriers at the Commonwealth level to allow the

introduction of a professional foster care model was supported by the Victorian

and ACT Governments.[65]

Cost savings

6.63

Dr McHugh argued that a professional foster care model would deliver

significant cost savings to government by diverting children away from

residential care. In a professional foster care model, children with complex

needs who would otherwise be placed in residential care could be supported by a

full-time, professional foster carer.[66]

Dr McHugh estimated that a proposed professional foster care model developed by

the SPRC and Berry Street (see Box 6.6) would cost $86 900 per placement,

significantly less than the maximum funding allocation per placement for

residential care services in Victoria of $233 448 per placement.[67]

Box 6.3 – Best practice – Foster Care Integrated Model

The Foster Care Integrate Model (FCIM), developed by Berry Street and the SPRC, consists of four interlinked components:

- foster parent recruitment, training and assessment;

- placement support;foster parent network support; and

- financial resources.

Dr Marilyn McHugh suggests implementation of FCIM's therapeutic model 'is not only likely to

result in better outcomes for children and young people in care, but will also result in significant

cost savings for government at all levels'.

A report by the SPRC commissioned by Berry Street estimates the implementation of the FCIM

model will require an initial substantial cost to establish, but by improving outcomes for children

will result in significant cost savings for all levels of government expenditure, including social

welfare, health services, juvenile justice, education and homelessness.

Source: Berry Street,

Submission 92, pp 5–6; Berry Street Submission 92, Attachment 3, pp 6–7.

ACIL Allen Consulting review of

professional foster care

6.64

As part of the second action plan (2012-15) of the National Framework,

the then Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous

Affairs engaged ACIL Allen Consulting on behalf of the Standing Council on

Community and Disability Services Advisory Council to undertake a review of the

barriers and opportunities for developing models of professional foster care.

The review defined professional foster care as:

[H]ome-based care; targeted at children and young people not

able to be placed in more traditional forms of home-based care; providing

intensive care integrated with specialist support services; receiving a salary

commensurate with level of skill; and participating in ongoing competency based

training.[68]

6.65

The review was presented in October 2013 and found there was a clear and

demonstrated need and demand for a professional out-of-home care service system

that could result in significant cost savings to states and territories. The

review noted the National Framework and the National Standards provide an 'important

enabling environment' to progress the implementation of professional foster

care models.[69]

6.66

The review recommended two options for consideration by state and territory

community and disability services ministers:

-

national agreement be sought on the policy parameters to enable

professional foster care in Australia (including the preferred model of

professional foster care and subsequent clarification of taxation and industrial

relations issues required to enable the model), and the subsequent development

and endorsement of a Framework for Professional Foster Care under the Second

Action Plan; or

-

agreement to the development of a nationally consistent set of

skills, competencies and (over time) accreditation for professional foster

carers, underpinned by national workforce development and planning.[70]

6.67

The committee notes this review has not yet been considered by COAG. The

committee notes the Australian Children's Commissioners and Guardians agreed to

write to the Minister for Social Services in May 2015 commending the report and

seeking an update on the government's response.[71]

Several submitters recommended the 'prompt consideration' of the review and 'determination

of a plan to remove barriers to the implementation of professional foster

care'.[72]

Committee view

6.68

The committee recognises the importance of volunteer foster carers in

the statutory out-of-home care system. The committee is concerned about the

long-standing challenges in recruiting and retaining suitable foster carers to

meet the increasingly complex needs of children and young people entering

out-of-home care. The committee supports the consideration of a national

approach to supporting foster carers, including the accreditation of carers.

6.69

The committee acknowledges that professional foster care has significant

support across jurisdictions and that it may provide an opportunity to deliver

better outcomes for children in care, particularly those children with complex

needs. While noting the complex issues and barriers involved in introducing a

model of professional foster care, the committee considers these can be

overcome. The committee notes the importance of tailoring a professional foster

care model that will best meet the needs of Australian children and young

people, such as the FCIM model proposed by Berry Street.

6.70

The committee notes the ACIL Allen Consulting review of professional

foster care models. It is the committee's view that the recommendations of this

review should be considered as a matter of priority with a view to introducing

a best practice professional foster care model across all jurisdictions.

Residential care

6.71

The committee heard there are a variety of residential care facilities

across jurisdictions. The Australian Association of Social Workers noted that

models of residential care vary from 'small to larger settings, with full time

carers or shift work carers, for children in transitional or permanent care'.[73]

For example, in Victoria, the average size of residential care facilities is

four occupants, and has declined from an average of 6-8 occupants.[74]

6.72

Most residential care facilities are administered by NGOs, rather than

directly by state and territory child protection authorities. Information

provided to the committee by state and territory governments indicated that

most jurisdictions outsource responsibility for managing residential care

facilities to NGOs, including data collection and training of staff.[75]

6.73

Across all jurisdictions, young children are generally placed in

home-based care. However, older children with complex needs are more likely to

be placed in residential care. Anglicare submitted that for children with

complex and challenging behaviours, residential care becomes the 'default

option'.[76]

The Victorian Auditor‑General's 2014 report into residential care

provided the following profile of children entering residential care:

[C]hildren in residential care have generally been exposed to

multiple traumas in the form of family violence, alcohol and drug abuse, or

sexual, physical and emotional abuse since they were very young. They may have

a parent who is in prison or a struggling single parent with mental health

issues. Some have been born to mothers who were very young, often with a

violent partner. They usually have other siblings in care, and one of their

parents may also have been in care as a child. They are usually known to child

protection at an early age. They come to residential care typically as a young

adolescent, having experienced a number of placements in home-based care that

have since broken down or were only available for short periods of time. They

often come to residential care with little warning and with few belongings. On

their 18th birthdays, if not before, they leave the protection of the state.[77]

6.74

In some cases, children may be placed in residential care because of

breakdowns in foster care or relative/kinship placements. The Western

Australian Government told the committee that of the 4 237 children in care at

30 June 2014, 82 had entered residential care from a foster care breakdown and

46 from a relative/kinship breakdown.[78]

Funding models and costs

6.75

As noted in Chapter 4, outcomes for children in residential care are

significantly worse than other forms of care. A number of submitters noted that

despite the high costs of delivering residential care services, particularly

therapeutic programs that require additional levels of staffing and support

services, outcomes for children in residential care are poor.[79]

6.76

As Figure 6.2 shows, the cost of residential care per child is

significantly higher than other forms of care. In Victoria, the average cost

per placement for residential care is $392 631 per year, compared with $27 980

for non-residential care. In Western Australia, the cost is much higher, with

an average of $640 244 per child for residential care, compared with $33 307

for non-residential care.[80]

The Victorian Auditor General's 2014 report noted that placements for some

children with significant and extreme needs cost close to $1 million per

year.[81]

6.77

The committee heard that despite the high level of expenditure on

residential care, current funding models are not adequate to meet the high

demand for residential placements. In March 2014, the Victorian Auditor-General

found that Victoria's residential care system was 'unable to respond to the

level of demand and growing complexity of children's needs' and had been

operating beyond capacity since 2008.[82]

6.78

Declining numbers of foster carers was said to be a contributing factor

to the demand for residential care. For children with complex needs, Berry

Street noted for children with complex needs:

placement in residential care becomes a default placement

option. Children who might have been placed with trained and supported foster

carers face the prospect of being placed in residential care alongside highly

traumatised young people who are still recovering from their own childhood

trauma and may pose a risk to other children.[83]

6.79

Support for a range of flexible funding models that focuses on the needs

of the child was expressed by Mr David Fox from MacKillop Family Services:

What we need is funding that is able to allow the sector to

be innovative in developing new models of service delivery that are responsive,

not to the fiscal environment, but to the needs of the child or young person in

care. What we need is a suite of flexible models that are responsive to the

needs of young people.[84]

Training support

6.80

A number of submitters and witnesses noted the need for trained staff

who had the capacity to address the complex needs of children and young people

placed in care. The Salvation Army explained:

Residential workers and residential care is not about a house

with some people who look after kids; it is about an environment where day in

and day out staff have the capacity to influence the behaviour the wellbeing

and the future trajectory of young people.[85]

6.81

The committee heard that one outcome of the existing funding structures

is lack of adequate training and development for residential care workers.[86]

Anglicare suggested that 'the funding structure in place dictates that the

people who provide support in these settings are among the least qualified and

are the least paid.'[87]

Similarly, the Tasmanian Government noted that staffing in some residential

care arrangements:

...is characterised by staff that do not have specialist

professional training or accreditation (which is currently unavailable),

inadequate supervision and limited access to training. This has resulted in

situations where the only service provided to the most chaotic and vulnerable

children, is adult monitoring rather than specific care intervention.[88]

6.82

The Victorian government has recently introduced a unique approach to

address the lack of training for residential care workers. The Residential Care

Workforce Quality Initiative is in the early stages of development (see Box

6.4). The committee considers that an evaluation will need to be undertaken to

assess whether this initiative may provide a best practice model for other

jurisdictions.[89]

Box 6.4 – Best practice – Residential Care Workforce Quality Initiative

The 2014 Victorian Auditor-General's Report into residential care found the lack of qualifications,

skills and training for carers in residential care facilities contributed to poor outcomes for children. The report noted therapeutic models of care showed better outcomes for children largely because

these models focus on building staff capacity.

In response to recommendations from the Auditor-General, the Victorian Government introduced

the Residential Care Workforce Quality Initiative in 2015.

The initiative involves:

- development of a future capability framework, including consideration of the introduction

of a minimum qualification for residential care workers; and

- piloting of a professional support program which comprises training and specialist

support to embed theory into practice.

Source: Victorian Government,

Submission 106, p. 10; Victorian Auditor-General, Residential Care Services for

Children, 26 March 2014, p. x.

Committee view

6.83

The committee is concerned that outcomes for children and young people

in residential care are poor compared with other forms of care. The committee

acknowledges that the way residential care is funded and delivered facilitates

these poor outcomes, and that a disproportionate amount of funding is allocated

to a model that does not support children and young people.

6.84

As discussed in relation to relative/kinship carers, the committee

notes demand pressures affect the ability of child protection authorities to

place children in appropriate placements. However, evidence to the committee

suggests that available residential care facilities do not provide appropriate

accommodation or support for children and young people.

6.85

The committee acknowledges the importance of having trained specialist

staff to assist children and young people in residential care, particularly

those with complex needs. The committee supports the development of nationally

consistent training for all residential care staff.

Cross-jurisdictional issues

6.86

In addition to the specific issues discussed throughout this chapter, the

committee identified a number of cross-jurisdictional issues that affect relative/kinship,

foster and residential care placements, including:

-

implementation of therapeutic models;

-

financial support;

-

carer qualifications and

-

role of the non-government sector.

Therapeutic care

6.87

A number of submitters and witnesses expressed strong support for the

introduction or expansion of 'therapeutic models' of care to address the trauma

many children and young people experience as a result of separation from

family, abuse or other issues.[90]

The importance of culturally appropriate therapeutic care was highlighted as

particularly significant for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities,

particularly relative/kinship carers.[91]

6.88

The committee heard that 'therapeutic care' is not clearly defined and

can be applied across a range of different types of care. A 2011 study by the

Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) into residential care noted that therapeutic

models of care respond to:

...the complex impacts of abuse, neglect and separation from

family. This is achieved through the creation of positive, safe, healing

relationships and experiences informed by a sound understanding of trauma,

damaged attachment, and developmental needs.[92]

6.89

AIFS noted that because there is no clear definition of therapeutic care,

it is difficult to identify how many therapeutic models currently operate

around Australia.[93]

Mr Julian Pocock from Berry Street told the committee:

[T]his tag of

therapeutic care and trauma-informed practice, in our view, is being slapped on

things right across the out-of-home care system without a sector-wide and a

nationally agreed robust framework of: what is therapeutic care and what are

the essential elements that make care therapeutic and deliver good outcomes for

kids?[94]

6.90

Some jurisdictions have implemented, or plan to implement, therapeutic

models across residential care and foster care placements.[95]

Queensland is currently trialling four therapeutic residential care facilities.[96]

Victoria is piloting and implementing therapeutic models of foster care and

residential care.[97]

Under its five year out-of-home care plan, the Victorian Government aims to

increase the number of therapeutic residential care place to 140 by the end of

2015, with a long-term view that all residential placements will be

therapeutic.[98]

Similarly, as part of its five year out-of-home care strategy, the ACT Government

plans to introduce annually reviewed therapeutic assessments and plans for all

children upon entering care.[99]

6.91

A range of CSOs, including Berry Street, Baptcare, the Salvation Army

and Connections Uniting Care also deliver a range of therapeutic services, from

early intervention to residential care.[100]

Berry Street submitted children and young people in out-of-home care have a 'right'

to therapeutic treatment.[101]

6.92

However, the committee heard that the majority of children in care do

not have access to therapeutic supports. A 2011 study by the Centre for

Excellence in Child and Family Welfare estimated that just four per cent of

children and young people are placed in an 'articulated and adequately resourced

therapeutic framework'.[102]

Mr Basil Hanna, Chairman of the Community Sector Roundtable for NGOs and

Government in Western Australia, told the committee that although all jurisdictions

recognise the importance of therapeutic models, few have been implemented:

We know that

providing them with a home and a safe place and love and nurture, for a large

majority of these children, is not enough. And we know that is because a trauma

from abuse causes impairments of the development pathways of a child's brain.

We know the effects of that, and we know what will happen to these children's

lives if we leave them untreated. We know that there will be a massive cost to

society as they become adults, whether in prisons or in relationships or in

mental health, or just the fact that, cognitively, they cannot function as well

as other children will function in schooling. Yet when they come into

out-of-home care, with all this knowledge that we have, we still have a system

that, whilst acknowledging it is an issue, does not really address it.[103]

6.93

A number of witnesses recommended the establishment of a nationally

agreed practice framework for trauma informed therapeutic care to assist

governments and service providers in implementing a broader range of

therapeutic supports.[104]

Relative/kinship care

6.94

As discussed throughout this chapter, the complex needs of children in

relative/kinship care placements are often not recognised. As a result, carers

are not supported to address the trauma and abuse experienced children in these

placements. A number of submissions supported the introduction of a supported

model of relative/kinship care that better supports children and carers.[105]

6.95

The committee notes there are few best practice models for therapeutic

relative/kinship care in Australia or internationally.[106]

Foster care

6.96

A number of submissions highlighted the importance of specialist or

therapeutic foster care programs to address the needs of

children in out-of-home care.[107]

The committee heard that all jurisdictions provide both a 'general' and

'specialist' model of foster care, depending on the needs of children.[108]

For example, Key Assets provides general and specialised models of care in WA,

SA, Queensland and NSW.[109]

Key Assets told the committee that its specialist model of care is informed by

a therapeutic 'team parenting framework' to stabilise placements for children

with complex needs (see Box 6.5).

Box 6.5 – Best Practice – Key Assets Team Parenting Framework

Team Parenting provides a systemic framework for stabilising foster care placements. The

framework consists of four key phases:

Phase 1 – Stabilising the placement within the agency

Phase 2 – Providing appropriate response to the young person's needs

Phase 3 – Modelling appropriate emotional responses

Phase 4 – Building resilience

Key Assets reports that based on evidence from the initial application of the framework in the

United Kingdom and Australia, Team Parenting has demonstrated its effectiveness in positively

impacting both trauma and attachment related disturbances and the challenges associated with

children in foster care placements.

Source: Key Assets,

Submission 88, pp 7–10.

6.97

There is no national data on the numbers of children accessing the

specialist programs that operate in all Australian jurisdictions.[110]

The committee notes that there are also no comprehensive examinations of

therapeutic foster care across jurisdictions.[111]

6.98

Mr Rob Ryan, State Director for Key Assets in Queensland, told the

committee that:

[T]here is no magic bullet in any one location. The key to it

is putting the resources in place for all carers...Anyone who is managing and

supporting children in care requires wraparound support...[112]

6.99

The Victorian Government supports two models of therapeutic foster care:

the Take Two program (see Box 6.6) and the Circle Program (see Box 6.7). The

committee heard that because of funding restrictions in Victoria, fewer than 10

per cent of children in out-of-home care receive support through the Take Two

program, and only seven per cent of children in foster care in Victoria have

access to the Circle Program.[113]

Berry Street submitted that the Circle Program has not been expanded, despite

positive evaluations of the benefits of the program.[114]

Box 6.6 – Best Practice – Take Two Program – Berry Street

The Take Two program is a developmental therapeutic program for children and young people in

the child protection system in Victoria. It has operated since 2004.

The Take Two program is led by Berry Street in partnership with:

- La Trobe University Faculty of Health Science;

- Mindful Centre for Training and Research in Developmental Health; and

- Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA).

The Take Two program is funded by the Department of Human Services and accredited by the

Australian Council on Healthcare Standards until 18 February 2018.

The Take Two program is an intensive therapeutic service for children who have suffered trauma,

neglect and disrupted attachment. The program aims to provide high quality therapeutic services

for children of all ages and those important in their lives. It also aims to contribute to improving

the service system that provides care, support and protection for these children.

In its submission, Berry Street noted 'the impact of the Take Two program and availability of

therapeutic care has been profound'. A 2010 review of the Take Two program found it accepted

1063 referrals between January 2004 and June 2007. The highest percentage of children referred

were over 12 years old. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children made up 167 (16 per cent)

of referrals. The central message of the review was the 'positive and meaningful changes in the

lives of children who receive Take Two intervention'.

Berry Street notes limitations on funding mean that less than 10 per cent of children and young

people in out-of-home care in Victoria receive support through the Take Two program.

Source: Berry Street,

Submission 92, p. 12; 'Therapeutic care', Berry Street, http://www.berrystreet.org.au/Therapeutic

(accessed 25 June 2015).

Box 6.7 – Best practice – The Circle Program

The Circle Program was introduced by the Victorian Department of Human Services in 2007 within

the context of ongoing reform to improve outcomes for children and young people who have

experienced abuse and/or neglected and were placed in out-of-home care. 97 placements in The

Circle Program are available across Victoria.

The Circle Program has five key program components:

- enhanced training;

- intensive and well-integrated foster care support;

- therapeutic service to family members;

- specialist therapeutic support; and

- support network for the child and young person.

These components surround the child or young person in placement. As the child or young person

benefits from these components, so the carer also engages and develops as an informed and

confident therapeutic care provider.

The Circle Program is delivered by range of non-government agencies, including MacKillop Family

Services, Anglicare Victoria and Salvation Army Westcare. Training for carers and professionals

was developed and delivered by Australian Childhood Foundation and Berry Street Take Two.

A 2012 evaluation of The Circle Program by the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare

found there are positive outcomes for children and young people referred to The Circle Program.

The findings of the evaluation suggest The Circle Program can achieve excellent early intervention

results for children and young people at risk to prevent them from becoming entrenched in the care

system and experiencing developmental harm, and can also achieve excellent results where children

and young people in out-of-home care experience complex and entrenched difficulties.

The review recommends the Circle Program be expanded to be an option for all children and young

people entering foster care.

Source: Margarita Frederico

et. al., 'The Circle Program: an Evaluation of a therapeutic approach to Foster

Care,' Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare, Melbourne, 2012, pp 7

– 19.

6.100

It was put to the committee that one of the key challenges to implementing

therapeutic models of foster care is the high cost involved compared with

existing models of care. Mr Rob Ryan from Key Assets told the committee that:

The problem is that economically it is challenging. It is not

a cheap exercise to support all children in foster care the way that they

should be.[115]

6.101

However, a number of submitters suggested that although therapeutic care

is expensive, it may be more cost effective than placing children in

residential care. Mr Ryan told the committee that:

...where you invest money to support families and carers with a

wraparound support model you have a better chance of success. The money that we

save initially here is a false economy when these kids are churned through the

system and end up in residentials costing half a million dollars a year.[116]

Residential care

6.102

A number of submitters expressed strong support for therapeutic models

of residential care, noting the benefits of a therapeutic model in supporting

and improving long-term outcomes for children and young people.[117]

The Salvation Army submitted that 'a comprehensive and therapeutic response is

critical to support and improve long term outcomes for children and young

people in out of home care'.[118]

MacKillop Family Services submitted that therapeutic residential care was

well-resourced:

...allowing for more innovative and responsive staffing

arrangements, higher staffing ratios, better training for staff and carers and

access to therapeutic professionals.[119]

6.103

A number of submitters supported the implementation of nationally

consistent therapeutic care models for all residential care facilities.[120]

MacKillop Family Services recommended that 'all residential care should be

funded and delivered from a therapeutic perspective' accompanied by increased

funding commensurate to delivering enhanced therapeutic services.[121]

6.104

The committee heard that Victoria's therapeutic care model offers a good

example for other jurisdictions (see Box 6.8). An independent evaluation

undertaken by Verso Consulting of Victoria's therapeutic care pilot program

found that the model provides better outcomes for children and young people

than standard residential care.[122]

Dr Nicholas Halfpenny from MacKillop Family Services told the committee of the

benefits of the Victorian model:

For a very long time, residential care has been the end of

the line. I think it has been a place where young people who have been too hard

to place anywhere else have been and the system has waited for them to turn 18,

so they age out of the system. I think that the model in Victoria—therapeutic

care model—has been a great development. It has really reanimated residential

care as a better care option for young people.[123]

Box 6.8 – Best practice – Therapeutic Residential Care model, Victoria

In 2007, the Victorian Department of Human Services piloted the therapeutic residential care

model. The pilot was extended to 12 sites in 2008 and is delivered by Community Service

Organisations (CSOs). Therapeutic residential care provides a therapeutic specialist linked to each

home, an increased number of staff, mandatory trauma-informed training, planned care transitions

including matching of clients, and provision of a more home-like environment.

An independent evaluation conducted by Verso Consulting in 2011 of Victoria’s therapeutic

residential care model found that the model achieved better outcomes than standard residential

care. These improved outcomes included:

- improvements in placement stability;

- improvement in quality of relationships and contact with family;

- significant improvement over time in quality of contact with their residential workers;

- increased community connection;

- improvements in sense of self;

- increased healthy lifestyle and reduced risk taking;

- enhanced mental and emotional health;

- improved physical health; and

- improved relationships with school.

The Victorian Auditor-General's 2014 report into residential care noted 80 placements have been

funded under this model. CSOs delivering a therapeutic placement receive a loading of $74 850 on

top of their current funding level. The Commission for Children and Young People noted

therapeutic placements accounted for around 17 per cent of residential care placements in Victoria.

Source: Victorian Government,

Submission 106, p. 7; Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare,

Submission 99, p. 19; CCYPV, Submission 45, pp 17–18.

6.105

Mr Gregory Nicolau, CEO of the Australian Childhood Trauma Group, suggested

that the Jasper Mountain Centre in the United States provided the best example

of therapeutic residential care in the world (see Box 6.9).[124] Mr Nicolau explained

that, in the Jasper Mountain model:

children are sent away from the home in which they have been

abused and live in a large residence on the top of a mountain. It provides an

intensive residential treatment program with a therapeutic school; a short-term

residential centre; a treatment foster care program; a community based

“wraparound” program and crisis response services. The facility offers a

combination of traditional psychological and psychiatric interventions with

innovations in treating abused and emotionally disturbed children.[125]

Box 6.9 – Best practice – Jasper Mountain residential care

Jasper Mountain, established in 1982 and based in Oregon in the United States, provides a

continuum of programs that meets the complex needs of children and their families. Jasper

Mountain's programs are aimed at children aged 3 to 12 with backgrounds of abuse and neglect.

Programs offered by Jasper Mountain include intensive residential treatment, an integrated

therapeutic school, a short-term residential centre, treatment foster care, community based

wraparound and crisis response services.

The Stabilisation, Assessment and Family Evaluation (SAFE) Centre provides an alternative to

psychiatric hospitalisation. The length of time children stay in the program ranges from 3 to 90

days. Placements are generally supported by child protection and mental health authorities.

An outcome data report by Jasper Mountain on 13 children discharged from the intensive

residential treatment program in 2013 indicated:

- most of the problem behaviours children entered the program with were eliminated;

- all children experienced an average 59 per cent improvement in clinical goals and

objectives; and

- 75 per cent of children showed an improvement in relationship skills and ability to attach

and bond.

Source: Jasper Mountain

Centre, http://www.jaspermountain.org/index.htm

(accessed 27 May 2015).

Committee view

6.106

The committee recognises the potential of therapeutic models of care

that address trauma and abuse to improve outcomes for children and young people

in out‑of-home care. The committee is of the view that therapeutic foster

care and residential care models has contributed to better outcomes for

children and young people than existing forms of care. However, the committee

is concerned these models are undertaken on a relatively small scale and are

only available to a small proportion of children and young people.

6.107

Although there is a high cost in the short-term to deliver therapeutic

models, the committee considers that it is essential to ensure children and

young people receive the support to address trauma and abuse. The committee

also recognises the potential long-term benefits for children and young people,

and significant cost savings for all levels of government.

6.108

The committee also notes no consistent definition or application of the

way 'therapeutic care', as it is currently applied and sees benefit in the

development of national standards and guidelines for therapeutic care.

Financial support for home-based

carers

6.109

Most financial support for home-based carers is provided by state and

territory governments via carer allowances, which differ based on the age of

the child and the assessed complexity of their needs. Direct Commonwealth

funding specifically for carers is generally limited to family assistance and

income support payments.[126]

6.110

The committee heard that the allowances for home-based carers differ

widely across jurisdictions. For example, the 'general' allowance rate for a

child aged under five years old in the Northern Territory is $225 per

fortnight, whereas in Queensland, it is $463 per fortnight.[127]

6.111

Table 6.3 outlines the estimated carer allowances available for

relative/kinship and foster carers. As discussed above, while relative/kinship

carers are eligible for the same base rate allowances as foster carers, few relative/kinship

carers are able to access the additional special needs allowances. This data

was only received from some jurisdictions and does not include additional

allowances and reimbursements available for specific purposes (for example,

school fees, birthday presents, pocket money).

Table 6.4 – Relative/kinship and foster carer allowances

|

Jurisdiction

|

Fortnightly allowance

|

Additional special needs allowances

|

|

NSW

|

$455 - $688

|

Special needs + 1: $683 - $1031

Special needs + 2: $903 - $1360

|

|

VIC

|

$285.50 - $456.74

|

Intensive: $344.97 - $851.31

Complex: $923.12 - $1,443

|

|

QLD

|

$463 - $542

|

High support needs: $162

Complex support needs: $210 - $632

|

|

WA

|

$363.15 - $492.05

|

$72.63 - $393.64

|

|

TAS

|

$383.00 - $507.00

|

Level 1: $619.50 - $744.00

Level 2: $935.50 - $1060.00

|

|

NT

|

$225.30 - $966.60

|

Higher rates for children with complex needs

Remote area loading for parents in remote locations

|

Source: Responses to

Questions on Notice, May-June 2015

6.112

A number of submitters recommended that the committee consider 'the role

the federal government might play in working with the states and territories to

encourage national consistency to home-based care reimbursements.'[128]

Carer qualifications and training

6.113

The committee heard that there is a lack of consistency in

qualifications and training for carers in all types of care across

jurisdictions.

6.114

All carers are required to complete a range of checks prior to being

approved as carers, including 'working with children' checks, administered by

state and territory authorities.[129]

Witnesses recommended the introduction of a national working with children

check to allow carers to transition more easily between jurisdictions. Mr David

Pugh from Anglicare in the Northern Territory told the committee, that in