Chapter 4

The impact of income inequality on disadvantaged groups

Introduction

4.1

This chapter responds to the inquiry's fourth term of reference relating

to the impact of income inequality on disadvantaged groups within the

community. These groups include Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples, older job seekers, people living with a disability or mental illness,

refugees, single parents and women. These groups are vulnerable to poverty for

reasons that will be discussed. They are typically among the lowest income

earners in society and disproportionately represented among social security

recipients and public housing tenants.

4.2

This chapter focusses on the impact of low incomes on people within

these disadvantaged groups. The committee has had the opportunity to gather

evidence from various stakeholders on the underlying vulnerability of these

groups to poverty. No or low income among these vulnerable groups often acts to

entrench their disadvantage.

4.3

The chapter identifies the disadvantaged groups and the evidence of

their disadvantage. It notes:

-

the underlying disadvantage and discrimination that is faced by

people in these groups;

-

how this disadvantage contributes to their economic exclusion;

and

-

the impact of a low income or welfare dependency on a person's

housing, health, education and labour market opportunities.

The chapter concludes by noting that there are other

factors—such as geographic disadvantage and the nature of labour markets—that are

often experienced by people in these groups which serve to compound their

disadvantage.

Disadvantaged groups

4.4

Some groups in Australian society are more vulnerable to poverty and

disadvantage than others. This includes Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples, people with disability, people living with a mental illness, single

parents and newly arrived migrants (particularly those without English). For people

in these groups, a low income is typically a symptom of more fundamental

disadvantages that they face in everyday life. However, income is a key factor

in determining the economic wellbeing of these groups. In the absence of an

income or transfer payments to sustain a basic standard of living, a person's

physical and mental health often deteriorates and their capacity to enter or

re-enter the workforce and engage in community activities is diminished.[1]

4.5

There have been several research studies, over a considerable period of time,

which highlight the over-representation of these groups among the poorest in

society. They are over-represented among low income earners, welfare

recipients, the unemployed, the poorly educated and those living in public

housing. The combined effects of an established illness and a low income

mean that the health outcomes of many members of these groups tend to worse

than for the general population. As Dr Matt Fisher of the Southgate

Institute for Health, Society and Equity at Flinders University told the

committee:

People in the disadvantaged groups named in the terms of

reference are among those most likely in Australia to undergo both negative

material and psycho-social effects of low income, contributing to their

disproportionately high levels of chronic illness and shorter lifespans. An established

illness, of course, is also likely to impact on income by being a barrier to

employment, or through the costs of medicines.[2]

4.6

It is also important to remember that many Australians fall within multiple

disadvantaged groups. For example, in 2008, 41 per cent of young Aboriginal

parents were single parents.[3]

Refugees will often suffer mental health issues due to pre- and post-migration

experiences.[4]

Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples

4.7

Multiple studies over the past 40 years have highlighted the severe and

endemic nature of Aboriginal disadvantage in Australia.[5]

They have found that an Aboriginal person is not only more likely than a non-Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Australians to have a lower income, but is also more

likely to:

-

have poorer health;

-

a lower level of education;

-

be homeless;

-

be incarcerated;

-

commit suicide; and

-

have a lower life expectancy.[6]

Income inequality and Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples

4.8

The majority of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a low

income. The 2011 Census found that:

-

fifty-two per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people aged 15 years and over reported a personal income between $1 and

$599 per week, compared with 32 per cent of the Australian population;[7]

and

-

13 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged

15 years and over reported a gross personal income of $1 000 or more per week

compared with 33 per cent of the non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

people population.[8]

4.9

The Productivity Commission's November 2014 Key Indicators report

noted that:

The proportion of adults whose main income was from

employment increased from 32 per cent in 2002 to 41 per cent in 2012–13, with a

corresponding decrease in the proportion on income support. Increasing

proportions of employed people were in full time and managerial positions.

After adjusting for inflation, median real equivalised gross

weekly household (EGWH) income for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Australians increased from $385 in 2002 to $492 in 2008, but did not change

significantly between 2008 and 2012–13 ($465). In 2011–12, non-Indigenous median

EGWH income was $869.[9]

'Closing the Gap'

4.10

Income inequality is just one of a number of intersecting inequalities

that have combined to create the severe poverty faced by Aboriginal Australians.[10]

The current focus of Australian Governments is to reduce the level of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples disadvantage across a number of key

indicators. The 2014 Closing the Gap report found that progress towards reaching

targets on these indicators had been mixed. It noted that:

-

in 2010–12, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples life

expectancy was 69.1 years for males and 73.7 for females. In 2014, the

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) reported that life expectancy for the

Australian population was 80.5 for males and 84.6 for females.[11]

The report commented that 'progress will need to accelerate considerably if the

gap is to be closed by 2031';

-

in 2012, 88 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

in remote areas were enrolled in a pre-school programme. The benchmark is

95 per cent;

-

in terms of reading, writing and numeracy, 'only two out of eight

areas have shown a significant improvement since 2008'; and

-

'no progress has been made against the target to halve the

employment gap within a decade' (by 2018).[12]

Employment, unemployment and

exclusion from the labour force

4.11

Unemployment and exclusion from the labour force is clearly a

significant factor in the relatively lower incomes received by Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples people. The 2011 Census found that only 46.2 per cent

of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were employed, compared with

72.2 per cent of non‑Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people unemployment rate (9.6 per cent) was more

than double the rate for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (4.2

per cent).[13]

The proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people not in the

labour force (ie: neither employed nor unemployed) was 46.2 per cent compared

with 23.6 per cent among the non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people population.[14]

4.12

The 2014 Closing the Gap report cited employment data from the

Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (AATSIHS)

suggesting the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

employed fell from 53.8 per cent in 2008 to 47.8 per cent in

2012–13. The report did caution:

Some care is required in assessing progress on this target as

the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) counts participants in Community

Development Employment Projects (CDEP) as being employed. The policy goal is to

increase mainstream (non-CDEP) employment not the number of CDEP

participants–CDEP is not intended to be a substitute for mainstream employment.

There has been a large fall in the number of CDEP

participants from 2008 to 2012–13, which accounts for more than 60 per cent of

the decline in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people employment rate

over this period. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people mainstream

(non‑CDEP) employment rate also fell from 48.2 per cent in 2008 to 45.9

per cent in 2012–13. However, this fall was not statistically significant.[15]

4.13

The 2014 Closing the Gap report also noted AATSIHS data that only

30.2 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults aged

15–64 in very remote areas were employed in a mainstream job in 2012–13

compared to 51.4 per cent in inner regional areas.[16]

4.14

In the 2011 Census, Queensland recorded the highest unemployment rate

among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of any Australian

jurisdiction.[17]

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples unemployment rate in

Queensland was 19.5 per cent compared with the State's non-Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander peoples rate of 6.0 per cent. Ms Catherine

Bartolo, Chief Executive of YFS Limited, told the committee that literacy

and numeracy remain barriers to employment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples in Queensland. She also noted that the Queensland Government

no longer provides programs to assist people to develop the social skills to

obtain a job.[18]

Community Development Employment

Projects

4.15

The CDEP was an Australian Government funded initiative for unemployed Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people living in particular locations. The CDEP

offered paid (minimum wage) opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander participants to improve their work skills with the aim of securing

long term employment.

4.16

Introduced in 1977, the CDEP has been reformed and tightened over the

past decade with participant numbers currently less than a third of what they

were a decade ago. The current government's focus is on paid work for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people:

Our next priority is getting people into real jobs. Too

often, employment and training programmes provide ‘training for training’s

sake’ without delivering the practical skills people need to get real jobs.

The Government has commissioned a review of employment and

training programmes led by Mr Andrew Forrest. This review will provide

recommendations to make Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples training

and employment services better targeted and administered to connect unemployed Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander people with real and sustainable jobs.[19]

4.17

On 1 July 2013, the CDEP was integrated into the Remote Jobs and

Communities Programme (RJCP). As of 30 June 2014, the RJCP replaced the CDEP in

remote regions of Australia. CDEP participants are being transitioned to

mainstream employment services and CDEP wages have been replaced by income

support payments.[20]

4.18

The committee received evidence that the CDEP has not been evaluated on

the basis of its original objectives of cultural preservation and community

building. Associate Professor Michael Dockery of the Bankwest Curtin Economics

Centre told the committee:

...the CDEP was put in place because of a recognition that

people were living in remote areas where there was no labour market, so it was

silly to talk about: 'We've got to get people into jobs.' The CDEP was brought

in originally as an alternative to sit-down money. When you go back and look at

the program—it came in with the Aboriginal employment development program

following the Miller report in the 1980s—the objectives of the program were

explicitly community capacity building, cultural preservation and all those

nice words about building community and culture and capacity.

Over the years, when they were evaluated, those objectives

were just completely ignored. I have never seen a single measure...of: 'Well, did

we build community capacity? Did we promote cultural preservation, cultural

strengthening?' The objectives of those programs were completely ignored. In

the CDEP, there is a review every year; there are about 15 of them...

They more and more focus on, 'Did we get them into mainstream

employment?' And this is in the middle of the desert, where there are no jobs...

The whole objective was ignored. It is now assumed that this

was a failure, without a proper evaluation, in my view. One of the reports

criticised CDEP because it found people were happy on CDEP. It said: 'We can't

have people happy. They should be really unhappy and wanting to get into a

mainstream job.'[21]

Homelessness among Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander people

4.19

One-quarter of homeless Australians are Aboriginal. The 2011 Census

found that there were 105 237 homeless people in Australia of which 26 744

were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people.[22]

The November 2014 Key Indicators report stated:

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are

overrepresented amongst those who received assistance from specialist

homelessness agencies. Although only representing 3 per cent of the Australian

population in 2011, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people represented

around one-fifth (22 per cent) of [specialist homelessness services] SHS

clients (AIHW 2013). However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and

non‑Indigenous people sought services for similar reasons.

In 2012-13, domestic/family violence was the second most

common main reason both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and

non-Indigenous people sought SHS (24.0 per cent and 22.4 per cent

respectively), after accommodation difficulties (30.6 per cent and 30.1

per cent respectively). For both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non‑Indigenous

SHS clients, the proportion for whom domestic/family violence was the main

reason for seeking assistance increased as remoteness increased (17.0 per cent

and 19.4 per cent respectively in major cities compared to 45.0 per cent and

55.3 per cent respectively in very remote areas).[23]

4.20

The committee heard that Aboriginal people from remote areas can find it

difficult to adapt to living in an urban environments. Professor Daphne Habibis

of the University of Tasmania told the committee:

It is very well established that when Aboriginal people move

from remote communities into larger population centres they are very vulnerable

to homelessness. There is to some extent a culturally-sanctioned norm of living

in open spaces, but that comes with very high health costs if they do that for

any length of time. They are also exposed to environments of access to drugs

and alcohol, which can be very damaging for them. They may not have the money

to return home, so providing ways to support people who move to large

population centres is very important but it is also providing avenues for them

to return home if they are not living in an appropriate environment in the city

centres.[24]

Incarceration

4.21

At 30 June 2013, there were 8,430 prisoners who identified as Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander. This represented just over one quarter (27 per cent)

of the total prisoner population (30 775).[25]

The age standardised imprisonment rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander prisoners at 30 June 2013 was 1,959 Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander prisoners per 100 000 adult Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

population. The equivalent rate for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners

was 131 non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners per 100 000

adult non‑Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population.[26]

Recidivism

4.22

The rates of recidivism among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners,

both adult and juvenile, are significantly higher than those for non-Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander prisoners. Figure 4.1 is drawn from the November

2014 Key Indicators report. With reference to the figure, the report

observed:

Nationally, 77.0 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander prisoners on 30 June 2013 had a known prior imprisonment, with this

proportion remaining relatively unchanged over the past 13 years. The

proportion of non-Indigenous prisoners with known prior imprisonment was

50.9 per cent, also relatively unchanged over time...

Nationally, 77.9 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander male prisoners had experienced prior adult imprisonment, compared with

67.8 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander female prisoners.

The proportion was higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander male

prisoners compared with non-Indigenous male prisoners (except in the ACT) and

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander female prisoners compared with non-Indigenous

female prisoners (except in Tasmania).

Figure 4.1: Proportion of prisoners with known prior adult imprisonment

under sentence, by sex, 30 June 2013

Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples education and training

4.23

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have lower levels of

education compared to non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. A

recent Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report found that in 2011, 26

per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians aged 15 years

and over completed a non-school qualification compared to 49 per cent of non-Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Australians.[27]

4.24

School retention rates are also significantly lower for Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander peoples people than for non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples Australians. The federal government has stated:

Getting children to school is the Australian Government’s

number one priority in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples Affairs.

Poor attendance means that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

find it hard to perform at school. We must break the cycle of non‑attendance

to ensure today’s kids are educated and equipped to become future leaders in

their communities.[28]

4.25

In 2013, there were around 180 000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander students attending school full-time. The majority of these students

attended a public school. In 2013, the national apparent retention rate for

Year 7/8 to Year 12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students was 55.1 per

cent compared with 82.9 per cent for all other students. Nonetheless, the Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander school retention rate has increased significantly,

up from 39.1 per cent in 2003.[29]

4.26

The committee did hear of positive outcomes in terms of both retention

rates and Aboriginal education programs. Ms Anne Hampshire of The Smith Family highlighted

the achievements of two such programs:

We are running a more intensive form of our scholarship

program in Centralian Middle School in Alice Springs. It is initially focused

on Aboriginal girls, but it is a mixed program because the Aboriginal community

wanted it to be a mixed program. There is very little in the Aboriginal girls'

space in terms of programs. There is a 12 per cent difference in attendance

rates for Aboriginal girls on the program compared to Aboriginal girls in the

school not on the program. It is more intensive, so our ratio is three

coaches—we call them 'coaches' deliberately—for 25 students. There is a

whole wraparound support, experiential trips, breakfast with a mentor, regular

activities and regular touch points for the girl and their family in the

context of a supportive school environment. We have a 12 per cent

difference in the attendance rates...

Learning For Life is well established as well. We have been

doing much more refined work around the outcomes. Our Aboriginal attendance

rates on our Learning for Life scholarship are 86 per cent. So our average

attendance rates are higher than national Aboriginal attendance rates

generally. Our average primary attendance rates are 90.4. So these are very

consistent good figures, but we are obviously working harder to increase them

again.[30]

4.27

At the public hearing in Hobart, the committee took evidence from the

Youth Network of Tasmania. The Network's Chief Executive Officer, Ms Joanna

Siejka, highlighted the success of a case-management approach:

Youth Connections is a really effective service working with

young people who are either completely disengaged from schooling, from the

workplace and from family right across the board—no connections whatsoever—or

have some connections. It provides case management support to assist them to

work out what their pathway will be and to support them to maintain that. They

are very, very high risk clients. It has a very high rate of success with young

people of Aboriginal and Torres Strait background.[31]

4.28

At the public hearing in Rockingham, Mr Craig Comrie of the Youth

Affairs Council of Western Australia, drew the committee's attention to some

significant initiatives in the State to equip and support Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples young people to enter the workforce or education. As he

told the committee:

I want to mention in particular the ICEA Foundation, run by

Lachie Cooke, and the Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

Mentoring Experience—AIME—where young people are trying to tackle issues in

local communities for Aboriginal people. It is actually young people who are

taking the leadership role and saying, 'We want something better in our

communities. We want something better for young people.' The main thing that

those two programs are doing that I think is having great success is focusing

on providing young people with mentors and role models that they can actually

have in their lives who are potentially successful in their area of expertise.

Providing them with someone that they can aspire to be is something that I

think we need to be looking more at. The energy of these organisations is

unmatched by many others. Seeing young people driving the agenda is something

we need to be encouraging more.[32]

4.29

At the same hearing, Mr Sameh Gowegati, the Chief Executive Officer of

the South Metropolitan Youth Link Inc. (SMYL), noted the progress that had been

made in Western Australia on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

school retention rates. He told the committee:

When we started our Aboriginal schools program in 1997, 18

per cent of Aboriginal kids in WA got to year 12. That was a disgrace. It was

not such a huge problem in 1997 because you could get a job with a year 10

qualification. By the time we got to 2000, you could not get into TAFE with a

year 10 qualification and the jobs were shrinking, so we had to come up with a

solution. The schools program basically got those kids into employment and

training with a host employer for a day a week, and they were staying at school

and doing a day at TAFE. We played around with it and tried to create a pathway

for Aboriginal kids. That program was successful. By 2008 we had in WA achieved

a completion rate of year 12 for Aboriginal kids of 52 per cent based primarily

on that program. So we had raised the retention rate of Aboriginal kids to year

12 from 18 per cent to 52 per cent by 2008. Commensurate with that, we have

provided about 3,000 Aboriginal kids with apprenticeships, traineeships and

jobs. These were kids who otherwise would not have participated and so

that, probably more than anything else in this region, had a fundamentally huge

impact on addressing that huge gap between Aboriginal poverty, equality and

everything else.[33]

4.30

However, Mr Gowegati expressed regret that retention levels had since

fallen in the state, in part because of a lack of commitment and structure to

funding programs. In terms of the SMYL program, he explained that:

The federal government pulled its funding out. The state

government decided that it would focus on excellence, not equity, and so it

basically damned the program. As a trainer, we kept it alive. We kept funding

it ourselves, but the numbers dropped. So instead of having 400 to 500

Aboriginal kids every year staying at school and completing year 12, the numbers

dropped down to about 180 that we could fund ourselves.[34]

4.31

The committee was interested in SMYL's role of identifying Aboriginal

children at risk of falling out of the mainstream education system and giving

them training on a wage. Mr Gowegati told the committee that schools approach

SMYL with details of children who are not attending school, are at risk of

falling out or who have been suspended. SMYL then matches the young person with

an employer. As Mr Gowegati put it:

...they are taking them on, because we are paying the wages for

them and managing the process, and, all things being equal, they will employ

them at the end of the program. It puts enormous pressure on the charity to

meet the wages of 500 or 600 kids every year—between Aboriginal kids and non‑Aboriginal

kids—which we have to do. Having said that, it is about the only thing we can

point to that actually gets these kids, who are completely disengaged, into the

world of education and employment with a 70 per cent success rate. So it does

work. As I keep saying, it is not a stick to punish them; it is the fact that

they are guaranteed income. They are being paid to go to work. That is what

gets them in.[35]

4.32

The committee considers the issue of funding youth and Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander employment programs in chapter 6 of this report.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander peoples' health

4.33

Poor health outcomes among the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population

remain an area of acute and ongoing concern. Australia's Health 2014,

released by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, found that Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Australians have a burden of disease two to three times

greater than the general Australian population and are more likely to die at

younger ages, experience disability and report their health as fair or poor.[36]

4.34

The Productivity Commission's 2014 Key Indicators report found

that the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continues to

lag well behind that of the general population. Some of the report's findings

included:

-

in 2012–13, 39.3 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Australians aged 15 years and over reported their health status as

excellent or very good. This was a decrease from 43.7 per cent in 2008;

-

in 2012–13, around one in seven (13.6 per cent) of Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander Australians aged 18 years and over had not consulted a

GP/specialist in the previous 12 months—a decrease from 20.6 per cent in

2004-05 and 19.4 per cent in 2001;[37]

-

the hospitalisation rate for chronic conditions for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander Australians was more than four times the rate for

non-Indigenous Australians;

-

the hospitalisation rate for potentially preventable acute

conditions for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians was more than

twice the rate for non-Indigenous Australians;[38]

-

between 2001 and 2012–13, the crude daily smoking rate for

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults declined from 50.7 to 44.4 per

cent. A similar decline in non-Indigenous smoking rates meant that the gap in

(age adjusted) daily smoking rates remained relatively constant at around

26 percentage points between 2001 and 2011–13;[39]

-

in 2012–13, 69.2 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander adults were categorised as clinically obese (39.8 per cent) or

overweight (29.4 per cent). Only 27.7 per cent were considered to be of normal

weight;[40]

-

in 2012–13, almost one-third of Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander adults (30.1 per cent) reported experiencing high/very high levels of

psychological distress, an increase from 27.2 per cent in 2004–05; and

-

the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults

experiencing high/very high psychological distress in 2012–13 was 2.7 times the

proportion for non-Indigenous Australians in 2011–12.[41]

4.35

In its submission to this inquiry, the Social Determinants of Health

Alliance said that '[T]here is a clear relationship between the social

disadvantages experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and

their current health status (Carson et al. 2007)'.[42]

Ms Yvonne Luxford of the Public Health Association of Australia told the

committee that Aboriginal disadvantage in health can, and must, be rectified:

Social, economic, political and cultural deprivation have

directly contributed to much lower life expectancy and a high burden of disease

across diverse areas such as cardiovascular disease, accidents and injuries,

respiratory disease, renal disease and diabetes—such a high burden of

preventable disease that, as a society, we should simply be ashamed. We should

be ashamed because we can change it...[43]

4.36

Oxfam recommended in its submission that the new funding formula for

Aboriginal health services should be developed in collaboration with Aboriginal

Community Controlled Health Services and peak organisations.[44]

The committee agrees with this approach.

Culture and Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples' disadvantage

4.37

Any effort to address Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

disadvantage in Australia must identify and overcome the underlying reasons for

these poor outcomes. The committee has not focussed on these matters in any

detail during this inquiry. However, the committee does highlight the following

evidence from Associate Professor Dockery:

Throughout the history of discussion about what policies

should do in Australia to address Indigenous disadvantage, there has been a

constant assumption that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples culture

is a barrier to achievement. It is basically a story between two

camps—the self‑determination people, who think Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander people should have the right to choose what they want of our

culture and our ways, and the assimilationist camp, who say, 'We've just got to

get them out of their culture and into our culture and then they'll have better

outcomes.' This has been the dialogue and both sides assume the culture is a

barrier. Even the people who believe in self-determination say it is a barrier,

that there is a trade-off but it is a choice they have to make.

There is hardly any empirical evidence on this, and I think I

am one of the only people who has looked at Australian empirical evidence.

The empirical evidence suggests exactly the opposite. People who have

stronger identification and engagement with their traditional culture have

better outcomes. These are not just wellbeing outcomes; these are mainstream

outcomes—employment, education, being less likely to abuse substances, less

likely to end up in jail.

Whatever the solutions are, they have to, for a long time to

come, incorporate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples aspirations

relating to important things for them—attachment to country, engagement in

culture, kinship networks. Those things are very important. If you are going to

go down the path of, 'No, you've just got to have employment; you've just got

to increase your income,' it just will not work. In my view, you will add to

200 years of policy failure.[45]

People with disability

4.38

People with disability in Australia have—on average—lower incomes than people

without disability:

-

A 2011 report commissioned by the Australian Network on

Disability found that the average weekly income for a working-age person with a

disability is $344, nearly half that of a person without a disability ($671).[46]

-

Less than 10 per cent of people on the DSP earn an income and

close to half of those that do have earnings receive less than $250 per week. The

average duration on income support for people receiving the DSP is around 10

years.[47]

-

The 2012 ABS Survey of Disability Ageing and Carers found that

people with disability aged 15 years and over are more likely to live in a

household in the lowest two equivalised gross household income quintiles than

those without disability (48 per cent compared with 22 per cent).[48]

4.39

People with disability are under-represented in the Australian labour

market and workforce:

-

The labour force participation rate for those aged 15–64 years

with disability in 2009 was 54 per cent (compared with 83 per cent for those

without a disability).[49]

-

In terms of employment, 50 per cent of people aged 15 to 64 with

disability and 28 per cent of people with severe or profound core activity

limitation were employed compared with 79 per cent of people without

disability.[50]

-

A lower proportion of people with disability were in employment

after receiving employment assistance than the proportion without a disability.

Thirty-six per cent of people with disability who used Job Services Australia

streams 1–4 were employed post-assistance, compared with 49 per cent of all job

seekers who used the program.[51]

-

People with disability are more likely to be working part-time

than people without disability.[52]

-

Forty-five per cent of people with disability in Australia live

in or near poverty[53]

compared with the OECD average of only 22 per cent.[54]

4.40

People with disability in Australia also face poorer health outcomes

than the rest of the population. Some of these outcomes include conditions that

are unrelated to the specific health condition associated with the disability.

People with multiple chronic health conditions have reported spending several

thousand dollars a year on out of pocket health costs.[55]

The Disability Support Pension, the

cost of living and employment

4.41

In its submission to this inquiry, People with Disability Australia (PwD)

emphasised that while having a disability means that everyday life is more

expensive, the Disability Support Pension (DSP) is inadequate to cover for

this additional cost. Further, while the reforms to the DSP since 2010 have led

to a decrease in the number of people on the pension:

...they have not led to an increase in workforce participation

for people with disability. The perverse outcome of these measures is that more

people with disability are now struggling to survive on less income, deepening

the inequality in our communities.[56]

4.42

PwD was also strongly critical of the 2014 federal budget's proposals to

reassess DSP recipients against new Impairment Tables and introduce increased

job‑seeking requirements for people with disability (see chapters 5 and

6). It argued the need for government to address the barriers to employment

through a jobs plan, rather than simply tighten the eligibility requirements

for the DSP.[57]

Housing for people with disability

4.43

The availability of appropriate and affordable housing is a crucial

issue for people with disability. PwD noted that housing issues are a common

concern raised with its individual advocates. It said that:

-

only 28 per cent of people who receive the DSP own their own home;[58]

-

36 per cent of households affected by a disability and renting

paid more than 30 per cent of their gross income for housing (compared with 26

per cent of households with no disability); and

-

the majority of existing homes in Australia are not accessible

for people with disability.[59]

4.44

People with disability rely heavily on social housing options. In

2011–12, 34 per cent of all public housing tenants relied on the DSP as

their primary source of income.[60]

At the hearing in Logan, the Director-General of the Queensland Department of

Housing and Public Works told the committee:

Because of demand there is an increasing need to target

high-subsidy social-housing assistance to those most in need while still

ensuring that other low- to moderate-income earners can access assistance to

stay in or move to the private rental market. In other words, 20 or 30 years

ago social housing was provided to families; today it is provided to high—and

very high needs people. In around 55 per cent of social-housing dwellings there

is at least one tenant who has a disability and around 25 per cent of all

tenants in a social house have a profound disability.[61]

4.45

The committee shares PwD's concern that appropriate housing is provided

for people with disability. PwD has noted that the National Rental

Affordability Scheme (NRAS) is to be phased out, adding:

With no alternative to the NRAS, and no dedicated investment

at a federal or state level to improve appropriate housing availability, people

with disability will still have their housing choices constrained. For some

people this may mean that they are trapped in institutional type settings

because there are no alternatives for them to move to.[62]

4.46

The committee highlights the following observations of the Parliamentary

Joint Committee (PJC) on the National Disability Insurance Scheme in its June

2014 report into the progress of the NDIS trial sites:

[T]he availability of suitable housing for people with

disability was a significant theme in evidence from the trial sites. Witnesses expressed

a wide range of housing concerns including young people living in residential

aged care homes and the deinstitutionalisation of state-run large residential

centres. It is important to note that suitable housing for people with

disability is a significant issue that pre-dates the introduction of the NDIS.

The introduction of the Scheme is an opportunity for this issue to be

addressed. These matters, and the broader problem of the limited stock of

housing for people with disability, require policy leadership at the national

level and should be the focus of the Council of Australian Governments

Disability Reform Council.[63]

4.47

This committee shares the PJC's view that the NDIS presents important

opportunities for governments to address the issue of housing for people with

disability. Further, it agrees with PwD that:

The implementation of the NDIS, on time and fully funded,

will play an important part in addressing the barriers to social inclusion that

many people with disability face in Australia.[64]

If dedicated resources are not provided to guarantee

provision and accessibility of mainstream services for all people with

disability (such as housing, education, healthcare, transport), the

opportunities provided through the NDIS will not be realized and the inequality

of the majority of people with disability will persist.[65]

People with mental illness

4.48

Mental illnesses can have a debilitating effect on the sufferer and his

or her carer(s). Apart from the psychological and physical distresses of the

illness, the sufferer may have reduced productivity, experience

discrimination in the workplace, have periods of unemployment or be permanently

excluded from the workforce. It is clear that having a mental illness can lead

a person to being financially disadvantaged. What is not clear is whether a

person's financial situation could trigger a mental illness.[66]

4.49

The most common mental disorders are depression, anxiety and substance

use disorders. Less common, and often more severe disorders include

schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder.[67]

The National Mental Health Report 2013 estimated that:

-

two to three per cent of Australians—around 600 000 people—have

severe disorders (as judged by diagnosis, intensity and duration of symptoms,

and degree of disability);

-

another four to six per cent of Australians—about 1 million

people—have moderate disorders; and

-

a further nine to twelve per cent—about 2 million people—have

mild disorders.[68]

Access to health, housing and

employment

4.50

Mental Health Australia's (MHA) submission states that 'people with lived

experience of mental illness and mental health carers are over-represented

amongst people on the lowest incomes'.[69]

It noted that having a low income can affect a mentally ill person's ability to

access health services, housing and employment. In terms of accessing health

services, MHA argued:

[I]ncome inequality constrains the choices that people can

make regarding their health and wellbeing. Gap payments and other ‘out of

pocket’ expenses can make accessing services such as General Practice,

psychology and psychiatry cost-prohibitive for people on low to moderate

incomes.[70]

4.51

Mr Josh Fear of MHA told the committee that people with mental illness

face significant costs in addition to the basic cost of living and 'these costs

rise the more health services you need to access'.[71]

He expressed particular concern with the impact of the proposed co-payment on the

capacity of people to seek help with a mental health issue. As Mr Fear told the

committee:

GPs are often the first port of call for someone with a

mental health issue, both someone who has never experienced those symptoms

before and is worrying about what they mean and also people who have an

enduring mental illness that they need to cope with over time. In fact 1½

million GP services are provided every year for a mental health issue.

It is Mental Health Australia's position that a co-payment

will actually discourage help-seeking...We have as many government initiatives at

state and Commonwealth level which have tried to encourage help-seeking,

yet we hear from our members and from the broader mental health sector

that a GP co-payment will do precisely the opposite and discourage people from

getting help early.[72]

4.52

In terms of housing, MHA emphasised the vulnerability of mentally ill

people to poorer housing options, but also the benefit that stable housing can

provide to their recovery. It noted:

There is a strong correlation between homelessness and poorer

health and wellbeing especially in relation to mental health outcomes.

According to the ABS survey of mental health and wellbeing, for the 484,400

people who reported ever being homeless, more than half (54%) had a 12-month mental

disorder, which is almost three times the prevalence of people who reported

they had never been homeless (19%). In addition, specialist homelessness

services supported more than 41,000 people who identified as having mental

health concerns in 2012–13. Conversely stable housing has been shown to improve

chances of recovery from mental illness and having a place to call home is

widely acknowledged as a critical foundation upon which to build a place in

community and social life.[73]

4.53

In terms of gaining and retaining employment, MHA noted that 70 per cent

of Australians with a mental illness are employed. Still:

...rates of labour force participation are lower for people

with mental illness than average, suggesting that more needs to be done to

address the specific barriers people with mental illness face in relation to

paid employment.[74]

4.54

In evidence to the committee, Mr Fear elaborated:

We know that only 38 per cent of people with mental illness

work full time, compared to 55 per cent of the rest of the population. When we

look at people with serious mental illness, the rate of unemployment amongst

people with psychosis is 67 per cent, rather than five per cent. We know that

around 260,000 people on the DSP have a psychiatric disability. We also

know that around 200,000 people on Newstart have an identified mental illness.

I would strongly suggest that many more people on Newstart have a mental

illness that they have not disclosed to Centrelink. Part of that is to do with

the way that Centrelink deals with its customers and part is to do with the

stigma associated with having a mental illness.[75]

4.55

MHA emphasised the economic and social benefits of ensuring that people

with mental illness maintain their employment and productively participate in

the workplace. It proposes a number of measures to increase employment

participation by people with mental illness, including wage subsidies for

employers who employ people with mental illness. These proposals were also put

to the McClure Review on Welfare Reform.[76]

Mental illness and the NDIS

4.56

The committee is aware there is currently work being conducted into the

eligibility of people with psychiatric disabilities for a 'Tier 3' package of

supports under the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). Some people

with more severe psychiatric illnesses will have financial support to cover the

cost of private psychiatric appointments (among other major expenses). MHA

suggested that the NDIS will provide an individualised support package to 'around

one in four or one in five people with psychosocial disability'.[77]

4.57

The committee notes MHA's concern that carers of people with mental

illness are not currently able to access any kind of financial assistance from

the Commonwealth. This is not the case for carers of people with other

disabilities. Mr Fear suggested that this implied the government was 'picking

favourites' among disabilities. He suggested that there needs to be a review of

the way that assessments for financial support for carers are carried out.[78]

Refugees

4.58

Refugees are another group that face particular challenges in the

Australian labour market by dint of their (often short to medium-term) personal

circumstances. In 2012–13, the Australian Government granted a total of 20

019 visas under the Humanitarian Programme.[79]

The highest number of visas granted in 2012–13 (under the offshore

component) was in the Middle East region (55.7 per cent), followed by the Asia

region (34.1 per cent) and the Africa region (9.9 per cent).[80]

The income of humanitarian entrants

4.59

The renowned Australian demographer, Professor Graeme Hugo, has found

that humanitarian entrants to Australia have the lowest income of migrant

groups.[81]

Commenting on his findings, a 2011 Department of Immigration and Citizenship

report stated that over half of humanitarian entrants have weekly incomes under

$250, compared with just under 30 per cent for the other migration

categories:

[H]umanitarian entrants have the lowest proportion of nil or

negative incomes, which Professor Hugo identified as partly the result of

humanitarian entrants having immediate access to unemployment benefits. The

lower levels of income have other consequences, such as a lesser ability to buy

a house. The research showed that the more recent waves of humanitarian entrants

were slower to enter the housing market and were more likely to be renting. The

older waves and the second generation were, however, more likely to be on a par

with those born in Australia with respect to owning a home.[82]

Barriers for humanitarian entrants

in gaining employment

4.60

The Refugee Council of Australia (RCOA) identified the following

potential barriers to employment by refugee and humanitarian entrants:

-

limited English proficiency;

-

lack of Australian work experience and limited knowledge of Australian

workplace culture and systems;

-

limited access to transport and affordable housing close to

employment;

-

pressures of juggling employment and domestic responsibilities (a

particularly significant issue for women);

-

lack of appropriate services to support employment transitions;

-

the impacts of past trauma on health and wellbeing;

-

downward mobility and the pressure to accept insecure employment,

which can result in underutilisation of skills and hamper longer-term career

advancement;

-

lack of qualifications or difficulties with recognition of

qualifications, skills and experience;

-

discrimination and negative attitudes; and

-

visa restrictions (in the case of asylum seekers and temporary

humanitarian visa holders).[83]

4.61

Professor Hugo interviewed humanitarian entrants to gauge—among other

things—the barriers that they have faced in gaining employment in Australia.

Prior to migration these factors included exposure to violence, instability and

persecution, lack of education, lack of knowledge about the Australian

labour market, lack of documentation prior to migration and misinformation

about employment opportunities. Post-migration, the identified barriers

included: mental health issues; illiteracy and low English proficiency; lack of

opportunities or finances to have skills recognised; lack of knowledge about the

skills recognition processes; lack of established networks in Australia; and experiences

of racism and discrimination.[84]

4.62

Professor Hugo also found that 69.7 per cent of those surveyed had at

some time sent money to their homeland. It was not unusual for recent African

migrants to send 10 to 20 per cent of their weekly income to their families in

the homeland or in a refugee camp.[85]

4.63

The RCOA's submission to this inquiry focussed on the capacity of

refugee and humanitarian entrants to access income support payments. It noted

that these people tend to be younger than the general Australian population: between

2009–10 and 2013–14, 87 per cent of the 70 000 people who were granted

humanitarian visas were under the age of 35 when they arrived in Australia. The

RCOA argued that given their age profile, and the fact they often rely on

income support payments during their early years of settlement, refugees are

'likely to be disproportionately affected' by the 2014 budget measures.

4.64

The RCOA emphasised that refugee and humanitarian entrants are often

'desperate to find stable employment'. Accordingly, it argued:

...the application of punitive financial “incentives” to

refugee and humanitarian entrants would represent a serious misdiagnosis of the

reasons for their (initially) lower participation in the workforce and cause

significant financial hardship without enhancing employment outcomes.[86]

4.65

The committee considers that a longitudinal analysis on how humanitarian

visa holders have fared in the Australian labour market over the first 10 years

of their settlement would be very useful. It would be particularly worthwhile

for this study to combine quantitative data on humanitarian entrants' income

levels over time with qualitative surveys—of the type conducted by Professor

Hugo—which identify the barriers and the keys to obtaining and retaining

employment.

Older workers and those at risk of

poverty in retirement

4.66

The terms of reference for this inquiry direct the committee to consider

the impact of income inequality on older workers and workers at risk of poverty

in retirement. Within this demographic, there are varying degrees or actual and

potential hardship and disadvantage. There are:

-

older unemployed people;

-

pensioners living in poverty;

-

those older workers on a low income with no assets or retirement

savings;

-

parent carers; and

-

those on relatively good incomes who have suffered investment

losses and the prospect of insufficient savings to self-fund their retirement.

Older unemployed people

4.67

Older unemployed people can face particular difficulties regaining

employment. A substantial number of older Australians of working age are not

employed. Department of Social Services data show that in September 2014,

there were nearly 400 000 job seekers receiving the Newstart

Allowance. Of these, 79 163 were aged over 50, nearly 20 per cent of all

Newstart recipients.[87]

4.68

The Department of Social Services has noted that between 2010 and 2013,

there was a 41.2 per cent increase in people in their 50s and 60s receiving the

Newstart unemployment benefit, much higher than the overall growth across all

demographics.[88]

Older people are more likely to be unemployed long-term than any other group.[89]

4.69

At the Logan hearing, Ms Bartolo told the committee that some of YFS

Limited's clients are older men in their late 50s who have lost their jobs and

cannot meet their commitments.[90]

Ms Mary D'Elia of Baptcare emphasised that unemployed older Australians living

on the Newstart Allowance have an income level 'generally acknowledged as

inadequate'. She argued that the pension age should not be raised to 70 years

without a simultaneous increase in the level of the Newstart Allowance.[91]

4.70

The committee recognises and supports government initiatives to assist

older unemployed Australians to gain work and encourage older workers to remain

in the workforce. The number of Australians aged over 55 (both male and female)

participating in the workforce has increased since the early 1990s. The ABS has

found:

In 2009–10, there were around 5.5 million Australians aged 55

years and over, making up one quarter of the population. Around one third of

them (or 1.9 million) were participating in the labour force. People aged 55

years and over made up 16% of the total labour force, up from around 10% three

decades earlier. The participation rate of Australians aged 55 and over has

increased from 25% to 34% over the past 30 years, with most of the increase

occurring in the past decade.[92]

Pensioners living in poverty

4.71

In its submission to this inquiry, the COTA Australia (COTA) stated that

older people are consistently over-represented in poverty statistics. It noted

that incidences of poverty are high for single older women and single older men,

as well as older couples.[93]

4.72

COTA did recognise that changes to pension arrangements in 2009

alleviated the levels of poverty. As part of these changes, the aged pension

increased and indexation arrangements were introduced that fixed the age

pension to a proportion of Male Total Weekly Average Earnings (MTAWE) and set

the biannual indexation at the best of the Pensioner And Beneficiary Living

Cost Index, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or MTAWE.[94]

4.73

Welfare agencies told the committee that increasingly, older homeless

people are presenting to them in need of assistance. Ms Cheryl Fairclough of

Baptcare in Tasmania told the committee:

More and more agencies are seeing older people homeless for

the first time in their lives at retirement, particularly older single women.

Studies by the University of Melbourne looked at the fact that, even in the

buoyant years of 2001 to 2007, one in 12 older people suffered severe

disadvantage and poverty. Certainly, for single pensioners, one-third,

generally, are suffering financial and housing stress.[95]

4.74

Ms Fairclough's colleague, Ms D'Elia, told the committee of the

particular relevance of seniors living in poverty in Tasmania. She noted:

By June 2013 more than 17 per cent of Tasmanians were aged 65

and over—the highest percentage of any Australian state or territory. As an

aged-care agency, Baptcare is particularly concerned with the growing poverty

and housing insecurity amongst seniors. Indeed, around 40 per cent of the

aged-care residents at our Baptcare Karingal community facility in Devonport

are financially and socially disadvantaged. We also have a target of 30 per

cent of our home care packages being provided to disadvantaged aged clients.

4.75

Baptcare and COTA both expressed strong concern at the plans to shift

the indexation for aged pensions from a percentage of the average male weekly

earnings to the lower baseline of average weekly earnings and then indexing

pensions to CPI instead of wages growth. In terms of the impact of this

measure, Baptcare identified a particularly vulnerable group as grandparents on

the aged pension or on Newstart with responsibility for caring for their

grandchildren.[96]

Older workers on a low income with

no assets

4.76

Of great concern for the committee is the cohort of older Australians

who have lived for many years on a low income and who face a retirement without

assets. The committee is aware that the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in

Australia (HILDA) Survey contains data on Australians' asset holdings by age

group. The eighth statistical report contained the following table (Table

4.1). The report noted:

...in all age groups, there has been a decline in home

ownership between 2001 and 2010, but the largest declines have been for people

aged 35 to 54 years. One way of viewing these changes by age group is to take a

‘birth cohort’ perspective. Thus, the homeownership rate when aged 35 to 44

years was 4.5 percentage points lower for the cohort born between 1966 and 1975

than for the cohort born between 1956 and 1965; and the home‑ownership rate

when aged 45 to 54 years was 5.5 percentage points lower for the cohort born

between 1956 and 1965 than for the cohort born between 1946 and 1955.[97]

Table 4.1: Rates of home ownership by age group (%)

|

|

Mean rate over 2001 to 2010

|

Change in rate 2001 to 2010

|

|

18–24

|

10.4

|

–0.3

|

|

25–33

|

43.1

|

–1.8

|

|

35–44

|

67.8

|

–4.5

|

|

45–54

|

77.9

|

–5.5

|

|

55–64

|

83.3

|

–1.1

|

|

65 and

over

|

82.7

|

–1.1

|

Source: Melbourne Institute of

Applied Economic and Social Research, Families, Incomes and Jobs, Volume 8,

2013, p. 93.

4.77

In additional information provided to the committee, the Queensland

Council of Social Service (QCOSS) noted:

One of the significant challenges older people who live a

life-time of low income is their inability to purchase a home. Without a home

of their own many of these older people rely on the private rental market to

meet their housing needs and face a significant struggle meeting the high cost

of renting which can absorb a large proportion of income.[98]

4.78

This issue will be returned to in chapter 6 of this report in the context

of how negative gearing limits the stock of owner-occupier housing, forcing

low-income renters to accept market rental rates.

4.79

The Western Australian Council of Social Service (WACOSS) told the

committee at the Rockingham hearing that early intervention is needed to ensure

that older workers facing retrenchment are provided with retraining

opportunities while they are still employed. As Mr Chris Twomey, WACOSS's Director

of Social Policy, told the committee:

...there is some interesting work that the commissioner for age

discrimination is currently doing that is looking at the opportunities to do a

scan of older employed people in their mid-50s who are in the industries,

as in South Australia, that are at risk of winding up and that the best

opportunity to intervene and retrain is while these people are still at work.

As soon as they are unemployed, they have all of those additional barriers to

finding more work. That is a promising area to respond to.[99]

4.80

In September 2014, the Hon. Susan Ryan AO, the Age Discrimination

Commissioner, told the National Press Club in Canberra:

...we don’t want to see a repeat of the South Australian car

manufacturing industry collapse, where middle-aged skilled workers were laid

off and left—initially at least—with no advice and no direction as to how they

might find new jobs.

What workers in this situation need – and virtually every

individual does at some point in their working life – is a structured process

by which they can review where they are and plan for their ongoing participation

in employment.

That is why I am calling today for a National Jobs Checkpoint

Plan. I am urging a high profile, widely supported, and nationally coordinated

approach to helping all people at midlife to check where they are and change

direction if they need to. This national approach can be developed by

governments, industry and vocational education providers working together. I

see TAFE right at the center of this Plan. TAFE colleges have the required

training skills and links with local employers and government programs, but

these links need to be strengthened and supported for vocational education

everywhere throughout Australia.

...Initially under this Plan, anyone approaching 50 could

attend a local TAFE to get a skills analysis, and basic advice about which

sectors are growing and need workers, where the jobs are located in that

region, and what skills and credentials are required to secure one. A

well-targeted checkup and redirection at 50 could set a person up for another

20 years work, age pension age rules notwithstanding.

This is not a crisis management plan, it is a preventative

approach that would have older people recharging and moving smoothly into their

next stage of employment.[100]

4.81

The committee believes that the focus on well-coordinated, preventative

approach based on vocational education and training is sound. It will require

an appropriate level of investment from the Commonwealth and State Governments

and a framework whereby older workers in declining sectors can be effectively

case managed. Chapter 6 returns to this issue.

Parent carers

4.82

Another cohort of older person at risk of financial hardship is parent

carers. The long-term sacrifices that these parents make in caring for their

child often leaves them without an income, a career or any assets. The

committee heard from Ms Sarah Walbank of Carers' Queensland that:

The lack of appropriately skilled and affordable locally

based care services leaves them [parent carers] with no alternative except to

leave the full-time workforce and become full-time carers—a loss to the economy

that is rarely acknowledged in the public domain. This scenario is very aptly

illustrated by a quote from a carer to our annual quality of life report. She

says: 'My daughter is 24 years old but has funding for only 42 hours per

week. This means that we are together for no less than 110 hours per week. As a

consequence, I have no time to socialise, no assets and no way back into the

workforce.' The consequence of a parent carer's decision to leave the workforce

and accept more marginalised work is not merely a budgetary inconvenience; it

is a significant decision that has the potential to negatively impact the

family's financial capacity not only in their working years but also longer

term in their retirement years. As one carer said: 'The future security is

a subject that keeps me up at night and it constricts my chest. I have very

little superannuation left and I have no career. I have been a carer now for 14

years, and there is no end in sight. What will be my fate when I am aged and

impoverished.[101]

The challenge of self-funding

retirement

4.83

About eighty per cent of Australians of retirement age draw a full or

part pension.[102]

Despite the significant political emphasis and national investment in

superannuation, only a minority of Australians are self-funded retirees.

4.84

The aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) brought with it

public commentary in Australia (and internationally) about the impact of the

GFC on older workers' superannuation nest eggs. Would they still be able to

self-fund their retirement and if so, for how much longer would they have to

work? Journalist George Megalogenis wrote in October 2011:

In the three years before the GFC, when Australia was running

out of workers, men in their late 50s were the only grouping to reduce their

labour force participation. The lure of former Liberal treasurer Peter Costello's

tax‑free super payouts, promised in the 2006 budget, seemed to be driving

people into early retirement.

But the income shock of the GFC has reversed the trend. In

the three years since the GFC, men in their late 50s have been responsible for

the second‑sharpest jump in labour force participation across the

economy. Only women aged 60-64 years entered the workforce at a faster rate. The new

research by The Weekend Australian confirms the role the GFC has played

in the greying of the workforce.

But the bigger picture is just as interesting. The baby

boomers have known for some years that the compulsory super system wouldn't

deliver its promise of a self-funded retirement in their lifetime. The super

system only reached the 9 per cent contribution benchmark in 2002—when

employers had to kick in 9 per cent of a worker's wage into a super fund.[103]

4.85

The revenue collected from the previous federal government's mining

super profits tax was earmarked to increase the Superannuation Guarantee Charge

(SGC) from 9 per cent to 12 per cent. The repeal of the mining tax in this

Parliament has meant that this increase will now not occur until at least 1

July 2021.[104]

4.86

The Assistant Secretary of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU),

Mr Tim Lyons, told the committee that the freeze of the superannuation guarantee

charge will have a regressive impact. As he explained:

The delay in increases to the superannuation guarantee charge

will certainly result in lower retirement incomes from super being available to

middle‑income earners in particular but also low-income earners. Every

year that is delayed will result in a smaller pool of retirement income savings

for those people. The delay in the SG probably will not affect high-income

earners in the same way as much of the money that is pumped into the system is from

additional voluntary contributions that people make in order to access and take

advantage of the tax concessions.[105]

4.87

The committee has strong concerns about the SGC freeze. It not only

fears the regressive impact of this policy but highlights the contradiction of

the government seeking to boost retirement incomes and reduce reliance on the

aged pension while capping personal and employer contributions to

superannuation.

Gender and inequality

4.88

There has been important recent research into the gender pay gap in

Australia. In November 2014, Curtin University academics Associate Professor

Siobhan Austen, Associate Professor Rachel Ong, Dr Sherry Bawa and Associate

Professor Therese Jefferson published research findings which showed that Australia's

gender wealth gap has widened sharply over the past decade. Across all age

groups, the disparity in average wealth between single men and single women grew

from $18 300 to $47 000 been 2002 and 2010. The study found that single

young women had a little over half the average assets of their male

counterparts. The main reason for this differential was the growth in the value

of housing assets owned by single men.[106]

4.89

In terms of earnings, Associate Professor Austen and her colleagues

found that the differential between the average full-time male worker and the

average full-time female worker was 18.2 per cent in August 2014. This was the

largest differential since 1994. Associate Professor Austen noted that these

trends seemed at odds with the trends of greater female participation in the

workforce and the higher number of women in tertiary education than men.[107]

4.90

In evidence to the committee, Associate Professor Austen also commented

on research she has conducted into gender income inequality with Professor Gerard

Redmond of Flinders University. The central finding of this research was that

as more women have entered the Australian workforce since the 1980s, family

income inequality was 'generally been pushed downwards'.[108]

She explained this research to the committee in the following terms:

...we looked at the increasing trend in male earnings

inequality as well as female earnings unequally, which increased by a lesser

amount in the decades 1980s and 1990s through to 2007, but from a higher base.

The trend towards inequality in both earnings distributions was upwards.

In terms of family income inequality, we found the growth in

women's earnings within Australian households had a mixed effect on family

income inequality. In a period 1982 to 1995-96, women's earnings' growth had

what we call a disequalising effect on family income inequality. This happened

because, increasingly, the growth in earnings by women was happening in

households that were characterised by high male earnings.

From 1995 through to 2008 an opposite pattern emerged, where

we saw the growth in women's earnings occurring more substantially in

households where male earnings were relatively less. In that period, as women's

earnings increased, we saw it having a positive or equalising effect on

family-income inequality. These changes in trends were associated with big

changes in women's employment over those decades.[109]

4.91

Associate Professor Austen also drew the committee's attention to her research

on women's share of total income. She noted that this share 'still sits

somewhere below 40 per cent, at around 38 per cent' and portrayed the broader

picture in the following terms:

Women remain overrepresented in low-income groups...and

underrepresented in high-income groups within our community. We have not seen

much progress in women's share of income despite...the rapid rise in employment

and the rapid rise in education. There are several reasons for this. Women's

employment rates are relatively low. When they do work they tend to work

part-time hours, much more than men, and their wages when they are in paid work

tend to be relatively low as well.[110]

4.92

Mr Tim Cowgill from the ACTU told the committee:

...the gender pay gap is not only large but it has risen quite

substantially since the mid 2000s and it is now at its highest since the 1980s.

That is a concern in and of itself, regardless of the subsequent effects on

wealth inequality and other things. But, of course, if women on average are

earning less, they are likely to have less retirement savings and that compounds

over time.[111]

4.93

Welfare agencies corroborated the financial hardship faced by women.

Mr Llewellyn Reynders of the Victorian Council of Social Service (VCOSS)

spoke of 'the feminisation of poverty in Australia' and stated that 'the gender

pay gap is now at its worst level in 20 years'. He told the committee that

VCOSS has noted a growing number of incidents of women experiencing

homelessness, including older women, as well as a rise in Victoria in the

number of family violence notifications.[112]

Single parents

4.94

Single parents—the majority of whom are single mothers—are another group

that is highly susceptible to poverty and exclusion from the workforce. Twenty

years ago, the Australian academic Dr Michael Jones wrote:

Single parents—the major cause of the 'feminisation of

poverty'—are regarded as a recent and serious social problem in most western

countries... Poverty surveys repeatedly show single parents to be the most

vulnerable poverty group. Unlike most of the aged, single parents have not

accumulated the assets, especially a dwelling. Many have low skills and low

earning potential; inadequate low-cost childcare is a major impediment to

employment and self-sufficiency...Many single parents are young, so they can

face many years of dependency. This is damaging to their future, as well as

being costly to the state.[113]

4.95

Recent data show that in terms of both workforce participation and

income, single parents fare less well than couples with dependent children. In

its 2013 report, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare provided the

following data (as of June 2011):

-

lone mothers headed 86 per cent of single parent families with

children aged under 15 years;

-

single parent families with a child under 15 were much more

likely to be jobless (39 per cent) than couple families (5 per cent);

-

fifty-four per cent of single mothers with a child under 15 were

in employment in June 2011, compared with sixty-seven per cent of single

fathers with a child under 15; and

-

a higher proportion of single mothers were in part-time work (30

per cent) than in full-time work (24 per cent). Conversely, a higher proportion

of working single fathers had full-time work (53 per cent) than part-time work

(14 per cent);[114]

-

in 2009–2010, the median weekly income of a single parent with

dependent children was $478 compared with a median income of $738 for a couple

with dependent children;

-

38.9 per cent of single parents with dependent children were in

the lowest income quintile compared with 16.9 per cent of couples with

dependent children;

-

only 3.6 per cent of single parents with dependent children were

in the top quintile of income earners; and

-

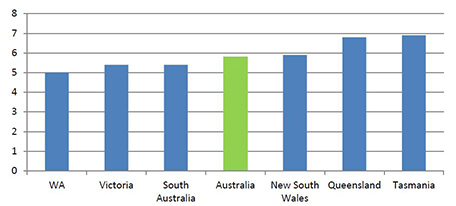

the highest childcare attendance rates were for children in