Chapter 9 - Identity and records

All he wants is to know

who he is. He is entitled to know his heritage. Our children and our

grandchildren are missing their heritage.[545]

9.1

For those people who have been state wards and home

children, the outcome is often lost contact with siblings and with their family

and place of origin. The Committee received many submissions from people who

had recollections of two, three, four or more siblings but they had not seen or

heard from them in many years. Other care leavers reported that they had found

that they had siblings only when, many years later, they viewed their files. Some

remembered parents, but did not know why they had been placed in care.

9.2

This is not only a heartbreaking experience but also

one that has a major impact on an individual's sense of self and identity.

There are no siblings to share birthdays or anniversaries. There are no

photographs, no medical histories, no school reports or personal mementos. Many

care leavers have been described as leading adult lives as 'parentless people',

feeling that they belong nowhere, isolated and being unable to establish

attachments which the majority of people take for granted.[546]

9.3

This chapter looks at the problem of loss of identity

and the search for the past through records held by both government and

non-government agencies.

Identity

People who make the decision to apply for their records are on a

journey of self discovery. They are dealing with the unfinished business of

their childhood. People searching want to understand more about the

circumstances that led to their placement in care, who their parents were and

whether or not they have brothers or sisters. In addition some people have

recollections about their time in care, and are keen to see if there is any

verification of the experiences they remember. We have an obligation to assist

in this journey and to help these adults complete what has been unfinished for

them, often for many years.[547]

9.4

The loss of identity and connection with family is one

of the most traumatic and distressing outcomes from a life lived in

institutional care.[548]

While in care, few children were told the story behind their placement or

encouraged to maintain connections with their families. Siblings were often

separated or not even told that they were related. Children were sometimes told

that they were orphans or came to believe that they were, simply because nobody

took the time to talk to them about their family backgrounds. Parents in many

instances were actively discouraged from visiting children. Inclusion in family

events, weddings and funerals, was virtually unheard of. One care leaver

stated:

Not only did I lose my identity, but I lost my Mother, my

Father, Brothers and a sister, my family home, my bedroom, my toys, my family

photos, my school friends at St Kevin's at Cardiff, Aunties, Uncles, my

hometown friends and connections...education...all blown away like points off the

stockmarket just as through it never existed. (Sub 360)

9.5

Another care leaver commented that while he was growing

up he didn't think that he had a mother or father until at the age of 12 when they

visited him at the home. He lost contact with his siblings, not seeing one

sister for forty years.

My Life has been terrible, I've been lonely all my life until I

was 62 years old. (Sub 283)

9.6

As adults, care leavers have sought the information

vital to reconnecting them to a family and to piecing together their childhood.

The search can be long. One witness, whose comments typified many received,

told the Committee that he had been looking for his mother and siblings for

over 50 years.[549]

Care leavers are searching for answers to a varied range of questions including:

-

Who placed me in care and why?

-

Who were my real parents?

-

Do I have any brothers and sisters?

-

Who arranged for my foster parents to care for

me?

-

Was the child welfare department involved?

-

How were decisions made to keep me in care?[550]

-

Why didn't other members of my family (uncles,

aunts, grandparents) look out for me?

9.7

Finding answers to these questions is crucial for many

care leavers in gaining a meaning to and understanding of their life.

I think the main concern that I have in telling this story is

that it reflects my having lived for some 40 or 50 years with whole lots of

questions nagging away at me. It was not until I was able to start getting

freedom of information access in the 1990s that the story I have told you

became clear to me. I have lived my whole life not knowing the answers to the

questions that obviously occur to you about why you were in an orphanage when

you were not an orphan and why your parents, who told you that they wanted to

have you, were not allowed to have you. It has taken all of that time for that

story to actually become clear-and it is not yet absolutely clear. I have had

to sift through and try to sort the evidence from the files, and sometimes

there are gaps in it.[551]

I had no idea of the actual story, and a lot of the reports I

had no idea of. It also gave me a sense of where I had come from. When I read

it I was crying because it felt like a story that I was reading, and I did not

totally relate it to myself. It was part of my journey to search and find out

if I was really the bad person that everybody said I was. It essentially

confirmed that there are some people who should not be social workers or in the

system...There were little bits and pieces. It was helpful to me because the only

source I had had from them so that I could find out about my mother and my

father was my aunt. It was a different source to go to so that I could try to

put the pieces together of who I was and who my family was.[552]

9.8

A particular issue for those who did not know or have

been unable to find records about who their parents were relates to possible

genetic health problems. As heart or other health problems have occurred in

advancing years people become apprehensive as they think of other possibly

inherited health problems they could contract, or more crucially, may pass on

to their children and grandchildren.

9.9

The lack of photographs and mementos is felt keenly by

care leavers. The pride with which some care leavers showed the Committee at

hearings photos of themselves, their siblings and peers that had been located

in files or at reunions was a moving testimony of the importance of photos to

care leavers. Photographs are a tangible link to the past, to their lost

childhood. MacKillop Family Services commented on the reactions of care leavers

to photographs displayed at reunions:

Some of the photographs on display identified the children by

name but many did not. People attending the reunions were desperately looking

for photos of themselves as children. Many had never seen a photo of themselves

as a child and many had no idea what they might have looked like when younger. Growing

up separated from parents and other family members means there are no reference

points to know what to look for, no familiar facial features or expressions to

guide one, no map of what constitutes a family likeness or resemblance. Whenever

someone found a photo of themselves, or was directed to a photograph by a

former carer, there was great excitement.[553]

Searching for records

9.10

Many care leavers provided the Committee with details

of their attempts to find records about their childhoods. There may be no

records left or the records are scattered amongst a number of agencies. It is

often a process of perseverance and luck. One witness recounted that, because

of the complete lack of records from a Salvation Army home, the only records

establishing that they had actually been at the home were a junior soldier

entry and the registration records at the local school.[554] The tragedy

for many care leavers is that they have little knowledge of the history of care

or of how to find the information they are looking for.

9.11

Unfortunately, many attempts to locate personal

information and records often meet with no success. Even for professional

researchers, tracing families is often difficult:

Piecing together family histories from very incomplete records

in multiple possible placements often from only slender leads is a challenging

task, even for experienced professional researchers.[555]

9.12

Freedom of Information legislation and the greater

willingness of some organisations which cared for children to make records

available to care leavers have improved access to records. However, problems still

faced by care leavers searching for personal and family records include the

lack of assistance to access records, destruction of records, the fragmentation

of records over a number of agencies, poor record keeping, privacy restrictions,

unsympathetic and unempathetic people on help desks and when records are

located, ensuring the access does not result in further trauma. As one care

leaver stated:

It is not just a matter of overcoming psychological barriers to

telling the story. It is also about finding the raw material. In my case (and

it is not unusual) I had to locate resources in up to a dozen different

locations and persevere with government agencies in the face of what, to put

the kindest interpretation on it, could be described as passive compliance with

FOI laws. In recent years NSW, Queensland

and the Catholic authorities have made significant progress in making data more

accessible but other states lag well behind. [556]

9.13

Some organisations are assisting former residents to

access their records. MacKillop Family Services established a Heritage and

Information Service in March 1998, funded by contributions from the

Sisters of Mercy, Christian Brothers

and Sisters of St Joseph. The Service was set up to assist with information about

time in care and to establish archives as the repository for organisational

records, including client records, from the seven founding agencies of MacKillop

Family Services. Over 100 000 individual records of former clients are now

noted on an electronic database. In establishing the Service, MacKillop Family

Services judged the following issues to be of paramount importance:

-

supporting former clients; and

-

searching for separated family members.[557]

9.14

Other organisations have also established services to

assist care leavers. However, the Committee was disturbed to hear stories of

requests to care providers for information being met with a total lack of

understanding, capacity or willingness to provide assistance. In some instances

no effort was made to assist the information seeker by reference to other

groups that may have been able to help or provide advice.

I contacted the Salvation Army, told them my story and asked for

information on [my brother]. I was told that they had no records from the

Nedlands Boys Home. They didn't even refer me to Child Welfare and also owing

to my own family commitments and finances I was unable to continue searching.

(Sub 184)

Since I began this 'learning about our past' process in 1998, I

have received grudging and minimal assistance and in some cases rejection from

these three institutions [responsible for care]. At this stage I have formally

received no files from these primary sources and have had to rely on sections

of files from secondary sources. (Sub 73)

9.15

The same issues and reasons that constrain people from

seeking counselling or other services from the providers who were responsible

for abuse can also apply when seeking records. Mercy Community Services (Perth),

for example, stated that:

We have heard from some past residents who come to us that they

have had several aborted attempts to phone or visit before they have been

successful. One woman told of driving into the main driveway over a dozen

times, over several years before she had the courage to get out and ask for

help. We have difficulty knowing how many other people might be in a similar

situation and how we might be able to create an easier way for people to

contact us.[558]

9.16

One suggestion provided to the Committee to improve access

by care leavers was third-party intervention:

As a ward of the State I find it very degrading to be told by

the Government that we have to confront the institution where I was sexually

abused...to try and find out information about myself. I feel that there should be a

Government body who would act on our behalf. This is not just for

myself, but for all the boys in the same situation who have to go to different

institutions where terrible memories exist, to grovel for information. (Sub 211)

9.17

In the directory of child care agencies produced for

the Anglicare Church,

it was noted that:

Of all the complex and difficult issues around the Stolen

Generations, child migrants and former wards, this issue of developing an

efficient and effective system for former residents of children's homes to

access any family information is surely the most manageable. Leaving it to

them, even their advocates, to contact one agency after another and search

through records themselves to piece together as much of the jigsaw as possible,

is both unfair to them and impractical and difficult for the agencies involved.[559]

Accessing records

9.18

The following discussion outlines some of the major

problems faced by care leavers in accessing records of their time in care.

State ward and non-ward records

9.19

The Committee has discussed in an earlier chapter the

range of reasons why children were placed in institutions in Australia,

as well as the range of institutions. In a study of state wards in Victoria,

Kate Gaffney

has noted that in order to receive state wards and those children committed to

government care, an institution needed to meet government standards and consent

to annual inspections. Institutions that met these standards were 'approved'

and received funding on a per capita basis for state wards in their care.

However, such institutions were not restricted to accepting only state wards

and thus state wards could be and were, mixed with children who had been

admitted to private care perhaps by a parent who had voluntarily placed the child

in return for a small fee paid to the institution. Ms

Gaffney has found this to be a considerable

source of confusion for people raised in institutions who mostly know only of

their own experience.

9.20

In addition, many privately placed children were sent

to institutions which did not receive, or did not seek, State government

approval. Thus, any parent could place a child in private accommodation,

usually provided by religious organisations, and in so doing, bypass the State.

9.21

Evidence was received during the inquiry that the

availability of records may be dependent on the status of the child placed into

care. Those children who were state wards are often more successful at

obtaining records because governments established personal files for each state

ward.[560] However,

many children who were placed in privately run institutions may not be so

fortunate in tracing records.

9.22

Ms Gaffney

considered that non-wards sent to non-approved institutions, may have a

particularly difficult time tracing their histories and finding answers because

they were largely invisible to the State authorities and thus would not appear

in State records.[561]

It is likely that these scenarios were repeated in other States.

Because we were not legally 'Wards of the State', we have no

records except for admission data. (Sub 6)

I just want to find who my mother was...I have tried everything to

find her and all I know is that her name was Shirley

Brown on my birth certificate... I was never a

State Ward, so cannot find out anything about the circumstances of my birth. If

I had been adopted, I would be able to have that information. I just want to

find my mother. (Sub 153)

9.23

CLAN also noted the problems of children in non-state

homes and stated that 'agencies and organisations which ran Homes in the past

do not appear to have felt the same obligation as governments to retain

records'. One example provided by CLAN was that of the non-state Home where one

of the organisation's founders was placed. It operated from the second half of

the 1940s until the late 1970s. There are no records for this Home or the

hundreds of children who passed through it.[562]

Locating records

9.24

Records that could provide care leavers with details of

their childhoods are often scattered across a number of agencies and stored in

a variety of locations. These might range from State child welfare departments,

courts, homes and non-government agencies. Some records have also been moved to

state archives and libraries. This makes the task of accessing the relevant

records especially difficult. The Australian Society of Archivists Special

Interest Group on Indigenous issues noted that 'records can be everywhere and

are rarely in the one place'.[563] While

referring to the records of indigenous children, the same applies equally to

the records of all children who have been in care. For example, photographs

from one home have been lodged at the Campsie Central Library.[564]

9.25

The problem of locating records is exacerbated in cases

where children were moved many times from children's homes to foster care. In

addition, many homes no longer exist or the names of homes and institutions

changed during their period of operation.

9.26

Some organisations have recognised this difficulty and

have produced guides to assist in locating records. One such guide, A Piece of the Story: National Directory of

Records of Catholic Organisations Caring for Children Separated from Families, has

been published by the Catholic Church. The

directory was originally conceived as the Church's response to the

recommendation relating to records in the Bringing

them home report. That recommendation called on the churches that had provided

institutional care to indigenous children removed from their homes, to identify

all records relating to indigenous families and arrange for their preservation,

indexing and access, in consultation with the relevant indigenous communities

and organisations. As the project progressed, it became apparent that

distinguishing Aboriginal children's records in Catholic institutions in many

parts of the country was not possible. The project was widened to include all

organisations of the Catholic Church that had been involved or that continue to

be involved in caring for children.

9.27

The directory provides details of all Catholic Church

institutions that were involved in care, the contact details and history of

each organisation including the dates of operation and the type of care

provided. The book contains information about the types of records that are

available and provides readers with guidance about how to find out information

for themselves or their family members.[565]

9.28

A guide to records of Anglican agencies providing

residential care for children has been produced on behalf of Anglicare by James

Boyce. For

the Record: Background Information on the Work of the Anglican Church with

Aboriginal Children and Directory of Anglican Agencies providing residential

care to children from 1830 to 1980 provides details of the location, access

and contact details for tracing records. Again, while the guide was principally

produced as the Anglican Church's response to Bringing them home, it also provides a guide to institutions which

provided residential care for non-indigenous children.

9.29

Some State governments also provide directories or

other services to assist in locating records. The NSW Government has produced a

directory, Connecting Kin, to assist

care leavers locate both government and non-government agency records. In Queensland,

care leavers may consult Missing Pieces:

Information to assist former residents of children's institutions to access

records for information about the records of departmental institutions and

those operated by church and voluntary groups. The Aftercare Resource Centre

(ARC), established following the Forde Inquiry, provides face-to-face and toll

free telephone counselling. ARC also provides advice regarding access to

individual records, documents and archival papers.

9.30

The Victorian Government is currently working on a resource

manual to the records of indigenous children in care: Finding Your Story. However, as with many homes Australia-wide, the

Victorian Public Records Office has found that the records of both indigenous

and non-indigenous children are kept in the same record keeping systems. As a

consequence, Finding Your Story will

contain information on all Victorian children's and babies homes, orphanages,

foster care programs, family group homes etc that it was possible to find

information on. The information includes the name of the home, the location of

records and access conditions and procedures.[566] The Department

of Human Services also provides services for former wards. The Department's

Adoption Information Services assists former wards to obtain their records and

provides counselling, support, search and mediation services.

9.31

While the directories try to be comprehensive and are

extremely useful, there are omissions and inaccuracies. Dr Joanna

Penglase, for example, noted that Connecting Kin, while it lists many

types of agencies in NSW, both government and non-government, does not include references

to private homes (ie those homes run by individuals as a business). Dr Penglase

noted that 'there is no way of knowing how many others like mine there might

once have been. Homes listed here were run by recognised churches or voluntary

agencies'.[567]

9.32

A comprehensive service to records is provided by the

Western Australian Government. Under the Managing the Past - Children in Care project,

the Department for Community Development has formed a representative committee

of placement agencies to help manage the provision of information relating to out-of-home

care across the State. This committee is developing the Children in Care

database and protocols for sharing information. This database will provide

accurate information on the numbers and names of children who were placed in

out-of-home care by the department. The database from 1920-2003 is complete and

includes 106 000 entries with an estimate that the actual number of

children is 56 000. The database contains names, alias, date of birth,

placement(s) details, dates of placement(s), record location, details and

comments field, including place of residence prior to care and place of

residence when leaving care. However, entries relate only to children who have

been placed into care with State government involvement. Children who went into

some form of private placement arranged by their parents, are not included.[568]

9.33

The Western Australian Department stated that:

[The database] will be an important tool for people who want

information about their background and support to trace family members. Our

hope is that, Australia

wide, more resources will be put into information provision and specialist

support to care leavers.[569]

9.34

The Department for Community Development commented that

it had seen a shift in attitude of those holding records since the Bringing them home inquiry and the child

migrant inquiry. The Department stated that:

...there is a real appetite and willingness of non-government

organisations and within our own department of like minds to keep good

information, keep client records, and I think there is a much stronger

awareness than in times gone past about the need to maintain such records. A

number of agencies which no longer provide institutions are in fact talking

with our information and records people about how the department can manage

those records for them, and passing that information back to us. So there has

been a huge amount of work undertaken in the last few years in terms of

improving and knowing where all the various records are.[570]

9.35

However, despite some positive responses, problems

still remain. While it is important that care leavers can identify where their

records may be stored, for records to be easily accessed they must be indexed

and preserved. Indexing the records of an institution can be complex. Some

records are in very old registers which are difficult to read and fragile to

handle while others have been stored haphazardly and must be carefully scrutinised

to ensure that accurate indexes can be made.

9.36

Indexing and appropriately storing records can be

labour intensive and very expensive. MacKillop Family Services indicated that

it had cost almost $200 000 to put all its records onto a computer

database.[571]

The Committee also received evidence that some agencies are digitising their

records, but the process is slow. Funds for these projects may not be available

and some organisations must rely on volunteer archivists. Mercy Community

Services stated that it has only indexed about 40 per cent of its records. This

has been done largely on a voluntary staffing basis as has the categorising of

its photo collection. Mercy Community Services is also attempting to source

funding for digital imaging of all its records.[572]

9.37

The Salvation Army also has been using the services of

a volunteer archives worker to work through its old files. It is estimated that

there are over 30 000 different records of many different types.[573]

Destruction of records

9.38

The Committee received much evidence about the record retention

practices of different departments, agencies and individual institutions,

ranging from almost total loss or destruction to well kept and fulsome records.

9.39

While former state wards may be more successful than

non-wards in locating information, this is not always the case. The Committee received

evidence that there has been considerable destruction of state records. For

example, in Western Australia

many government records have been destroyed. The Department for Community

Development indicated to the Committee that the first record of destruction of

files dated back to July 1938 when 12 000 files were destroyed from the

period 1886-1920. Files were also destroyed for the period 1921-1927. From 1951

the Department established a system of selection of files for retention. From

1960 it was agreed that adoption files would be destroyed after five years from

the date of the order; migrant files would be destroyed five years after expiry

of term or date of final action; and ward files would be destroyed 10 years

after expiry of term or date of final action. These destruction times were amended

over the years. From 1980 adoption files were transferred to the Adoptions

Branch and no files were destroyed.[574] The

Department indicated that now client files were held permanently and stated:

In the early decades a lot was destroyed, according to the

policies of the time. In retrospect we can now see the wisdom of holding on to

records.[575]

9.40

In South Australia

it has also been reported that many government records have been destroyed and

the Department of Family and Youth Services may only hold the index card of

those who have been in care. The Department stated that records were destroyed

in the late 1970s and early 1980s 'because of a prevailing philosophy and

community concern at the time that it was inappropriate for the Government to

hold files containing personal information about citizens'. However 'these days

we have strong policies and practices in place to make sure that records are

properly preserved and can be available to people seeking to access their

personal information to put the stories of their background together'.[576]

9.41

In New South Wales,

CLAN stated that state ward files were randomly selected and destroyed.[577] The

destruction of ward files seems to have been a widely accepted practice and the

Committee suspects that similar practices have occurred in other States.

9.42

Witnesses also reported difficulties in accessing state

records in Queensland where an oft

cited reason for the inability to locate records was that they had been

destroyed in the Brisbane

floods of 1974.

9.43

In some private institutions, the retention of records

has also been haphazard. As noted in For

the record, 'even when records were maintained, there has been no

requirement or expectation that they be kept indefinitely'.[578] CLAN for

example, stated that it knows of institutions which existed for many years and

housed hundreds of children, for which there appear to be no records extant.[579] One care

leaver related trying to find records of a Salvation Army home in South

Australia:

The Salvation Army [home] was shut down in 1973, I think. It had

been open for 30 years, but all the records they have in South

Australia at Nailsworth, which I have tracked down as

well, would not fill this folder. It is 30 or 40 years of a home run by the

Salvation Army which filled the whole journal of what happened.[580]

9.44

Records may have been lost because a specific event,

for example, many of the records of the Tally Ho Home were lost in a fire.[581] In other

cases, records cannot be found because they have been moved or misplaced. CLAN

stated that it had received information from a Melbourne City Mission worker who

reported that they had 'come across' a box of files in the archives related to

state wards who had lived in a children's home. CLAN commented:

These are records that presumably nobody knew about until this

moment, and we cannot know how many people had applied for access to them, only

to be told they no longer existed. The worker discovered them quite by chance.[582]

9.45

Whatever the reason for the destruction of files, the

outcome is still the same: care leavers are neither able to trace families nor

piece together their history. They also feel hurt and betrayed. As CLAN

commented 'these are children - these are families - who were not considered

interesting or important enough to even have their records kept'.[583] As a

consequence, 'it is very difficult to establish and

maintain a sense of identity in the face of such apparent indifference on the

part of the authorities who were supposed to "care" for you'.[584]

9.46

A further problem that has arisen relates to the preservation

of records which are old and fragile. Constant handling and inadequate storage

leads to further disintegration. Mercy Community Services for example,

indicated that it had records dating back to 1868. It has stored all records

relating to adoption using digital imaging and it has a long-term plan for the

digital copying of all records.[585]

Quality of record keeping

9.47

Once records have been located, care leavers are often

disappointed with the quantity and quality of information. Some people may be

fortunate to locate records that contain much information to help them piece

together family histories and their childhoods. Others are not so fortunate.

The United Protestant Association, for example, stated:

UPA has records for just over 3 300 children who were in

UPA care over a fifty year period. Record keeping in our early days was a mixed

bag, with some files containing a reasonable amount and some scant information.[586]

9.48

The reasons for lack of information are varied.

Sometimes the records were culled or destroyed. In some instances, where there

was no legal requirement, records were not kept. It was noted in For the Record that:

The records kept at many agencies before the 1950s were often

very limited. Until the 1970s there were very few or no legislative requirements

or guidelines for the types of records that should be kept. The most common and

reasonably widespread form of client records is an admissions register.

Punishment books are also reasonably common!...Some institutions have old

photos, even old film, which can be very helpful.[587]

9.49

It was also stated that the lack of records may have

been a deliberate policy. Catholic Welfare Australia

commented:

For many reasons some institutions did not keep minimal records

or in some cases people have not been able to access their records and this has

been a source of great pain and frustration. There appears to have been a

deliberate choice in some cases not to have too many details of a child's life

recorded so that the child could "start afresh" without the stigma of

illegitimacy, or broken relationships. Of course, that has meant that people

have often felt devastated because the records that they have been able to

access are so scanty and superficial. Also the sheer pressure of the day to day

work must have also contributed to not writing up records not to mention the

issue, of what kind of information should have been kept which was not e.g. medical

and dental records. As stated previously no uniform standards applied until

recent decades.[588]

9.50

Mercy Community Services also stated that sometimes

only very limited written records are available. Mercy commented that 'it can

be difficult to accept that several years of a life can be recorded by no more

than some one-line entries in a register'. While other information was kept at

the time, it may have been disposed of soon after the person left care. The

significance of such records was not always appreciated at the time and 'it is

also difficult to explain that there are some years where we have no records at

all (most of the 1950's)'.[589]

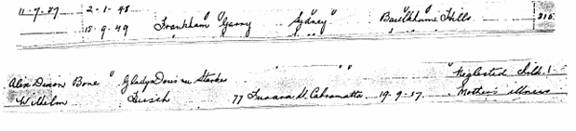

9.51

Examples of the absolute minimum of information

provided in response to requests were shown to the Committee. The following

information given to one person illustrates that a period of their life

consists of one line!

Other care leavers stated:

On request for information about myself while in St

Brigid's [from 4

to 16 years of age] I was sent one sheet of paper giving me a date of entry. I

think that sums it up correctly, these institutions hold no memory, no photos,

no medical, school reports nothing, and yet somehow we are meant to become

model citizens, HOW? (Sub 314)

I received in the post [from GSS Abbotsford] an A4 sheet of

paper stating my mothers name, dob, place of birth, religion, parents, date of admission & date of discharge. That was it. No explanation of what she was doing

there in the first place or any reports on any medical conditions she may have

had or any outings or basically any information that was telling except her

date of admission & discharge. As you can imagine I was more than just a

little disappointed that my mother's 2 1/2 years at this institution were

worthy of such minor details. (Sub 316)

9.52

Difficulties are not only encountered by care leavers with

the agencies which cared for children. Other institutions also may hold records

relating to care leavers. For example, one witness told of trying to access New

South Wales Children's Court records:

Western Sydney Records Centre Kingswood holds the Children’s

court Transcripts 1900-1960. Missing is the 1939-1950. When asking the most

important question is why are the war years missing? One receives all kinds of

answers from being lost to being burnt to being packed away. Under the Archives

Act brought in 1960 all records should have been released. Why were the 1939-1950

withheld? (Sub 24)

9.53

The impact of the paucity of information provided can

be devastating.

I find it more difficult to believe that my time at 'Lynwood'

cannot be found, which makes me sick to my stomach when I think about it, as I

feel I grew up a no name nobody.[590]

After 18 years as a 'Ward of the State' and some 32 years later,

I finally get enough nerve to have the audacity to ask the system for whatever

relevant details they may or may not have on me during my childhood...I get two

sheets of paper with about 9 or 12 lines on it, I look at these two sheets and

I am devastated, 18 years of my life on two sheets of paper. I ponder and

wonder this can't be all of my 18 years on two sheets of paper. (Sub 3)

9.54

Many care leavers cannot understand why there are no records.

One witness stated:

The most you get is date of entry and date of exit. There are no

records of childhood diseases, siblings or parents. Why did not the government

have inspectors to see that relevant data was recorded, not just notations in

an exercise book. (Sub 364)

Another care leaver noted:

No one can find any records about me...Our lives were changed

forever by this action and I have never been given or it seems now that I will

never have any context for this life changing action. Why is this? Why have I

never been told as an adult why the government came and took us? (Sub 57)

9.55

Even after a long and complex search of records, many care

leavers are disappointed with the outcome as they are unable to find answers to

many questions and they feel that they have been abused a second time. One care

leaver stated:

I looked forward with great anticipation to receiving those

records, hoping that they would give me an insight into those four terrible

years that my memory had successfully blocked out. But my hopes were in vain.

My total records consisted of one line - who my parents were and the date of my

admission to the orphanage.

I sat down and cried my heart out. It was as though the

emotional abuse of the orphanage was still continuing. As though Frank

and I never existed. I was told by MacKillop Family Services that there were

ample records for all other boys who were at the orphanage, however, as Frank

and I were private admissions by our father, we only rated one line each. (Sub

100)

MIM'S STORY

Being a "Home child" and not a ward

of the state meant very few records were kept of my formative years by the

people looking after me. At the time, with the rest of our troubles, it didn't

seem to matter. But now, as a 44-year-old woman, I want them desperately, and

not just for sentimental reasons. There is other documentation, medical records

in particular, that I need to understand what actually happened in that lost

childhood and what the consequences might be in later life. Twenty-four years

ago I was diagnosed with a blood disorder, thalassemia. My doctor says I have

suffered with some form of dyslexia and maybe even autism. He wants to know where

I might have got it from. I had to tell him I had no way of knowing. For the

last few years I have been trying to find any record of our childhood, anything

at all. I went to each of the Homes but they no longer exist or have changed

and say they hold no records from that time.

Mim finally discovered that the

records of one of the Homes she and her sisters were in for a long period had

been placed in the State Library of Victoria.

Finally, everything we imagined we needed to

know - medical history, photos, school reports, holiday visits - would be there

to see. I live in Far North Queensland, and it took a while to be able to get

back to Melbourne. When I returned last month, I was highly

excited. I dreamt about the answers I might find: why I could not read or write

properly until high school; what screening process the homes had for the people

who were allowed to take us out on weekends and holidays. More importantly, did

they record and monitor the uncontrollable behaviour problem I'd been afflicted

with, and what was that medication they forced into me on a daily basis? I got

to the State Library early and paced the foyer. The head librarian led me to

the desk where a large book lay all by itself. My heart was thumping as he

opened it. So there was the three-page history of our childhood. Mine was a

whole two lines:

M.S. Born Dec 1957. Sister of H.

"That's it?" I wailed. I burst into

tears. "How can that be?" I thought. After all this time I have

failed again. I have failed my sisters in finding their answers, too. But

really, it is the system, the government, my parents that have failed too.

Failed me, and thousands like me. That 60-year-old book contained hundreds and

hundreds of lost children's names...and nothing else. I felt I was being

ridiculed again. I wanted to create a scene. To yell and scream my years of

frustration and wait for the police to forcibly take me away. Instead, I went

to the nearest pub and got drunk. "How can that be?" I kept repeating

to myself. Our whole depraved and abused childhood. Silenced. Vanished. Gone,

just like that. I cried for myself and my sisters. I cried for all of the thousands

and thousands of dysfunctional adults I have never met, who have experienced

the same trauma as me. If we had been disabled, adopted, or if we had been

imprisoned or sent to a mental asylum, would we not have had more documentation

of our lives? Was that as far as the state's duty of care went?

Submission 22, p.13 (CLAN)

Information and comments contained in records

9.56

For those viewing files, the information contained in

them can bring back painful memories and may include comments that are written

in language that would not be acceptable today. People who have received

information from their files have referred to comments which indicated that the

welfare authorities were overly judgmental in relation to a family's social and

economic situation. One care leaver stated:

My parents may not have been the most admirable couple, but it

is evident that the authorities took action on the basis of their own value

judgements and personal preferences, instead of acting in the best interests of

their children. Examples litter the files. (Sub 18)

My file from DoCS contained many judgmental comments about my

mother and it seemed that they had no understanding that she was being

constantly bashed by stepfather. Also in my DoCS file, the district officers

observed that my stepfather was aggressive and smelt of alcohol but they never

looked any deeper. They never seemed to review the file to see that there was a

pattern and that he had a history of assault...It seemed easier for the welfare

to keep moving me from place to place rather than address the real problem

which was the physical abuse from my stepfather. (Sub 318)

9.57

Other comments in files can cause pain and distress to

the reader. CLAN gave the example of the use of 'high grade mental defective'

as a not unusual term applied to emotionally disturbed children who appeared

unresponsive to their 'carers'.[591] MacKillop

Family Services also noted that other terms that were common in past

psychological assessments 'cannot be read neutrally today'. MacKillop also

stated that the phrase 'disposal of the child' was one that people accessing

records find very offensive, 'because it reduces their life to that of a

commodity that can be disposed of like something that no longer has any worth'.[592]

9.58

Evidence of the lack of regard for the feelings of the

child in care can also bring back traumatic experiences and feelings of

inadequacy:

Finding out what went on in my life as a small child and a young

teenage girl was a little bit of a surprise. Also it made me angry, frustrated

and upset...As I read my file everything that was said was from the foster

families, I did not have any say on the way I felt or if I was happy with my

life. No case worker, no counsellor, no support person. Did I matter or did

they care what I was feeling as a child? (Sub 241)

9.59

For those who were given very little information about

their lives when in care, accessing files later often comes as quite a shock as

they may reveal family secrets, reasons for events that were previously unknown

or even information about unknown siblings.[593] One care

leaver stated:

I found out a lot from that file - more than I really wanted to

know. That's how I found out that I was classified as being "high grade

mental defective" and sent to "homes" for mentally retarded boys.

I was also able to piece together events into time frames. I had absolutely no

idea about how long I was in certain homes or about time in general. I was not

even able to tell the time in the homes. I also found out that the first time I

was taken from my parents it was at their request. Do you know how painful that

was for me? Everything I had suffered was because they didn’t want me. (Sub 94)

9.60

Care leavers are often distressed that many files

contain not only simple errors such as misspelled or incorrect names and incorrect

dates of birth, but also fundamental misinformation. The perpetuation of

incorrect or unreliable information, which appeared to have been accepted at

face value with minimal or no checking of its veracity, provided the basis in

some cases for significant decisions that affected the child's life. Witnesses

stated:

Dad signed the forms and left. Our mother’s signature was

neither sought nor required. No one thought it necessary to check Dad’s story...Nevertheless,

without ever being verified, this 'fact' became indelible in the Department's

file to be repeated in future documents. Once on the official file the 'facts'

were re-cycled until they became permanent truth. (Sub 18)

These mistakes were common, the files are something to behold,

they are inaccurate & sloppy, they make me think of the saying: 'Never let

the truth get in the way of a good story' as some of the stuff that is in my

file are just "nice" stories, it never happened. They often confused

you with another child I'm sure of that. (Sub 351)

The only records I have was a slip of paper from the Sisters of

Mercy that gives an incorrect date of birth and a baptism date on it, and a

piece of paper with details copied from a card file. Some of the details there

are incorrect as well. It has no entry after 1953 when my mother died. It

stated that my brother was at college and that I was discharged. I never left

that hellhole until late 1956. (Sub 330)

I received the paper from Major Sanz

and to my absolute disgust and dismay I was told 'we have not found a record of

you being at Goulburn Boys Home [Gill]'. Instead, I received a copy from Bexley

Boys Home stating that I had been there for about 6 years, my birthday

11.2.41, being sent to my mother and my mother being my future guardian. None

of this is correct, I spent about 9 years at Goulburn Boys Home [I was never at

Bexley], my birthdate is 11.3.41 and I was sent to my FATHER, and my FATHER was

my future guardian...How could they get it all so wrong? If they couldn't get

the paperwork right is there any wonder they couldn't get the "care and

training" right. (Sub 336)

Support for those viewing records

9.61

As noted earlier, accessing records is often a

traumatic experience for care leavers. Many who pinned their hopes on finding

answers in the files to questions they have had for many years are

disappointed. They may have to face the fact that the only record of their

entire childhood is one or two lines in a dusty register. Others will find

themselves described by language which is both confronting and distressing.

Others will uncover long-buried family secrets. None of these are reasons for

not facilitating access and discovery - the human need for identity should be

satisfied.

9.62

There is a strong need for support and counselling for

people before, during and after the file is read. The provision of such

services differs markedly. MacKillop Family Services for example, stated that

its service was 'personal' in recognition of the very emotional nature of

accessing information for the first time:

We try to meet each person where he or she is at, to work with

them at their pace and to explore areas with them as requested. Some people

have a very clear expectation from the outset of the questions they hope to

have answered. Some people are hoping for a lot of information. People who

contact our service are usually trying to recreate their childhood memories, to

search for missing pieces of the puzzle, to see if there are some facts to back

up what they remember and also for some people with no memory at all, it is to

use what records we may hold to create their story. Some people have their

story in their heart and know it, for others, the process is one of recovering

the story.[594]

9.63

Other organisations holding records provide services

for those viewing records. Dalmar, for example stated that it offers to fund

counselling for a limited amount of time to help people cope with the reactions

which occur when they see their file for the first time.[595] Mercy

Community Services provides support to past residents at the point of receiving

records and information about themselves. They also offer counselling at this

point if the process creates distress for the applicant.[596]

9.64

However, such an approach is not universal. In respect

of State records, the Committee heard evidence as to the variable manner with

which people are assisted from the helpful to a total lack of compassion,

empathy and understanding of the issues faced by people confronting their

childhood.

I had approached DoCS to access my file, not to access their

files to enable reunions. I had achieved that end ten years earlier, I was

after details of my wardship ie: how was it managed? What happened?...I had

phone conversation with [an officer], who told me that I would not get the

information I was after. What was prophetic was not her message but the tone of

voice she used, she was probably unaware of it, but her voice carried a hard,

sharp and cold tone, probably learnt controlling a large number of wards. This

tone of voice usually proceeded harsh treatment...I'm amazed [the officer's]

rejection had such a paralysing effect on me. I ran like a scolded cat, dropped

the idea of obtaining my file, or going anywhere near DoCS. (Sub 321)

One of the most disturbing things about my life, along with

thousands of others, is the offhanded way we are treated when asking for

records. (Sub 364)

9.65

The Committee was particularly concerned about the

different approaches taken by state organisations when providing records. CLAN

commented:

The level of support given to people when receiving the file

differs greatly between the states, many people are left to deal with the

harmful and damaging words about their personal history alone and totally

unsupported. Once again, it's a form of abuse.[597]

9.66

In Victoria,

Broken Rites related that it had approached the Department of Human Services to

establish an alternative system to sending a person’s records in the post.

Records which contain comments such as 'this person has a mental deficiency', and

'this person’s mother was a drunkard' cause great distress. Broken Rites

related that it had 'had police phone on a weekend, saying that some poor

person is in his car with the exhaust pipe through the back window, because he

received his records on Friday night'.[598]

9.67

In another case a care leaver was so disturbed by the

information in their file they were hospitalised:

In 1988 I got my files from the Department for Community

Services. I took those files home and read them. I did not like what I saw. A

week later I woke up and I was in la la land. I could not understand what had

happened. My friend took me to the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital D20

psychiatric ward.

When the doctor called me into the room I explained that the

Department for Community Services gave me my documents without any counselling

whatsoever.[599]

9.68

Even where there is a policy of having an employee

present to provide support for someone reading their file, this often ends up

as 'if you need me, call me'. One witness recalled the experience of accessing

the DOCS file on her time in care:

I thought it was a similar file to the one I received from

Dalmar but as I sat and read it by myself for three or more hours I soon came

to realise that I was wrong. That file was very hard to read because the

contents were to me very graphic. (Sub 241)

9.69

The following cases were provided to the Committee and

provide a picture of the lack of empathy provided to those seeking access to

records:

Ivy was phoned and told that she

could come into the office at Cessnock and read her file. Ivy

was left alone in a room from 2pm to

4.30. She only managed to read through half the file in the time she was

there...She was told [by the DOCS officer] 'if you need me you can call me'.

Ivy was totally unprepared for

the file's contents. Inside were letters, letters that her Father had written to

her and which she had never received, letters also from her siblings which she

never received and letters that she had written to her Father that hadn't been

posted, all those years ago. Can you imagine going to read your file and

discovering this precious correspondence. She was totally unprepared and no one

in DOCS warned her of the contents. This was a very emotionally draining day

for an elderly woman.

At 4.30 pm, Ivy

asked a DOCS employee 'Can I come back tomorrow?' the response was 'We might be

busy tomorrow, there might be a Child Protection Crisis and they may need the

room and you would have to move out'. Ivy said

that's OK, she would do that. They went to the appointment book to make an

appointment for tomorrow, Ivy was told there was no appointments and the staff

made one for the following Tuesday.

How could they make a 71 year old lady wait another 5 days to

read the file?[600]

9.70

While resource and other staff pressures may

contribute, this is a totally unsatisfactory situation for often elderly people

who are undertaking an exceptionally emotional experience.

Issues with access

Government records

Freedom of Information

9.71

Freedom of Information (FoI) legislation has been

passed in all Australian jurisdictions. The legislation covers personal

information compiled by government agencies. The Committee heard evidence that

some care leavers have experienced difficulty in accessing information under

FoI procedures. There were cases where information was provided only after

persistent efforts to pursue records and instances where large amounts of

information were withheld. Care leavers were particularly angry that the

material on files, even if years old, was still withheld. Witnesses stated:

If we do not get the finances to help people for medical reasons

or psychological reasons, at least give us the complete file. At least let us

read and put the jigsaw puzzle together as to why we went into these

institutions and why our parents were not given permission to come back and

visit us. At least let us have our information about ourselves...Each time I

have applied, I get that little bit more...I am trying again to get more

information. I want to know more about my parents. I have got nothing. My

mother is not of the mind to be able to tell me and my father died...I think

the information is there; they just do not want us to have it. But I want it.[601]

Incidentally, in the freedom of information process that I

started in 1994 -and I still have applications in - although I have been told

on a number of occasions, 'The files have been have all been released to you,'

further files have been found upon pursuing particular matters. The censorship

of the files was something that had disturbed me and I appealed as vigorously

as I could without getting into the legal process. I managed to retrieve whole

paragraphs from my own file. It galls me, having been a child in an orphanage

and never told anything about my parents, that now, when I am in my 60s, I am

being told, 'You can’t see what’s on your file.' It really galls me that some

perfect stranger, a bureaucrat, can see what is on my file but that I cannot.

So I go through this process of getting a letter with a paragraph missing and

having to write another letter and then six months later getting response. That

has taken a long time. It is now 2003; I started in 1994. I still have live

applications before government departments for information which is my

information. That really sticks in my throat.[602]

My endeavours to access my mother's personal records whilst at

Parramatta Girls' Home have been thwarted by bureaucratic red tape [Freedom of Information]. A recent

attempt at the State Archives in Kingswood resulted in

numerous phone calls to various government departments with each department

only too willing to suggest a further two phone numbers that might be helpful.

All to no avail!...I am an adoptee, my birth mother is dead, my grandparents

are dead and so is my natural father. Who may I ask are the bureaucracy

protecting? (Sub 154)

9.72

Some care leavers find it hard not to take the view that

organisations are trying to protect themselves when records are withheld or

parts of records are excised. Witnesses stated:

The Department...has numerous files, reports and information but

choose to release only minor non damning propaganda. (Sub 242)

I applied for my files, through freedom of information, through

DOCS. When I got them, they were so small that I thought ‘Wow, are these my

files?’ until I saw some of the other files. I applied for my real files and

got them, but a lot had been taken out. Then I looked again at the first lot of

files I had got and they were not even in them. So they all covered their

tracks. They left us so screwed up, but they covered their tracks.[603]

9.73

Bringing them

home commented on the restrictive application of FoI. In some States, there

are specific procedures for indigenous families in general or specifically for

children taken into care. These procedures are less formal than FoI,

discretionary and designed specifically for indigenous searchers. The report

noted that 'while they are often slower than an FoI application, they are

usually free of charge and research assistance may be available'.[604]

Assistance with records searches

9.74

During the inquiry, many witnesses commented on the

lack of assistance provided by governments to care leavers seeking their files.

Witnesses noted in most jurisdictions, assistance is provided to those who have

been adopted to trace family, however, the same assistance is not provided to

former wards of the state. One care leaver stated:

I have found out from one to two that have been adopted that they

have found out all the details. They have even found out that they have

brothers and sisters. It is made a lot easier if they were adopted.[605]

9.75

CLAN also commented that some State department websites

do not contain any information for former wards attempting to access their

files. On other sites, services for State wards are included with post-adoption

services. As CLAN noted, State wards have not been adopted and would not, in

the first instance, consider looking at adoption services to find out about

former ward services.[606]

9.76

CLAN also assists its members to obtain their ward

files or information about the institution they spent time in. In Victoria,

people who have been separated from their family of origin, including state

wards and adoptees, can access the search and support services provided by

VANISH.

Non-government records

9.77

Freedom of Information legislation does not apply to

records held by non-government organisations. The non-government organisations

apply their own procedure to accessing records and some agencies are more open

than others.

A few months back we went and opened our files at Dalmar. Up

until recently we were led to believe that they were burnt in a fire. About six

years ago we got access to a few things from a file, where we saw

letters-loving letters-our father had written that we never saw. We got a few

reports and things like that, but it was said that everything else was

destroyed by a fire in the walk-in safe. It would have been hard to ignite a

fire there.[607]

9.78

MacKillop Family Services noted that 'we believe very

strongly in a process of openness in terms of releasing our records. When we

first set up our service it would be fair to say that we received some

criticism from other providers for our willingness to be open - to release

records.'[608]

9.79

MacKillop went on to state that it had been given

records by the founding agencies to look after and for it to provide access

services to those records. Other congregations still hold their own records and

provide the service. When MacKillop Family Services was formed, the board chose

to fund the service. The service is consulted on a regular basis by Protestant

and non-religious organisations and by other Catholic organisations about the

model set up. MacKillop commented, 'it is probably true to say that for some

organisations today there is a fear of engaging with people that have grown up

in care in the past'. However, the board of MacKillop 'was not fearful about

that and saw that to go forward we had to acknowledge the past, which was not

always going to be good but was there'.[609]

Family information

9.80

Once people have found their own records, many try to

locate other family members. This search is often prompted by the discovery of

unknown siblings or that they were not in fact orphans as they had been told

and believed all their life.

9.81

However, the Committee heard evidence of the

difficulties faced by care leavers in accessing records of other family

members. In some cases, these records may hold information valuable to tracing

family members or the person's history. However, family information is treated

as information about a third party. Third-party information is treated

differently under privacy legislation to the personal information of the searcher.

MacKillop Family Services for example stated that 'we release records according

to the privacy legislation, which would mean that we could not release

information about a person to somebody else unless that person has given

permission for them to receive it or unless that person was deceased.'[610]

9.82

Witnesses provided examples of the impact of

restrictions on accessing family information.

Now also to find that I can't gain

access to files relating to my brothers from Family and Childrens Services

without permission from their children who I don't know. I feel that any

information that I get about myself is only half there because they were part

of my life and I have only half the story and am left with a hole in my life -

part of my identity is missing.

When I started the search I thought the ache in the corner of my

heart would be erased only to find that it has got larger. (Sub 184)

The Department decides I cannot have certain information about

MY parents. Why should the Department staff get to read the file about my

parents and then relate it to me? How dare the Department decide that I cannot

read about MY parents.[611]

9.83

It is very difficult for care leavers searching for

their history when the privacy requirements mean that a search may only access

information with the permission of next of kin. This is seen as unjust and

cruel. One witness stated:

There are large blanks in my sister's story. I am not able to

get access to her state ward file, because of privacy laws. These records will

help me to understand her life as well as my own. Siblings in 'normal' families

are able to get access to their family history through parents telling of the

family information. However, state wards often only have the state ward file to

go back to for family information.

Now that Pat's dead, I have to

have her husband's permission to get access to her state ward file. I have to

seek his permission for the release of 'our' family information. This is NOT

his family information...When this information was gathered, all those years ago,

he was not in anyway connected to my sister, yet the law states that this man

has the right to release or not release family information which does not

pertain to his history or identity. (Sub 119)

First, I wanted to get hold of his file, and then they put

obstacles up: ‘If he is alive we can’t do it under freedom of information, but

if he is dead and you can show us a death certificate we can provide you with

information,’ and stuff like that. To me it is just bureaucratic bungling all

the time and I just get frustrated about it because, as I say, they put me in

this situation. I am only asking for one thing of them: to say where Ralph

is, if he is still alive. He may well be dead. I do not know.[612]

9.84

Another care leaver searching for information about an

adopted brother killed in Vietnam

has been able to find his full name, place where killed in action, platoon and

photograph on the Internet. However, the Adoption Information Service could not

provide the brother's name or burial details until his other adopted brother's

(deceased) wife gives her permission to disclose the information as she is the

next of kin. The care leaver commented:

Blood is not thicker than ink lines on documents. Sure hope she

is not dead and will agree to meet and talk to and with me. As a mature 59 Y.O.

it would be my most treasured wish at this time to go to his grave and spend a

lot of time talking to him as we never met in his short 22 yrs and 2 days life.(Sub

157)

9.85

Bringing them

home also noted the problem of accessing strictly third-party information

to assist in building a picture of family history. While some agencies are

flexible and searchers receive information, others 'continue to interpret

third-party privacy restrictively and fail to assist searchers to meet their

requirements for third-party consent. The searcher can be denied the very

information needed to identify family members and re-establish community and

family links'.

The responsibility of government to provide this [family]

information to Indigenous people goes far beyond the standard justifications

for FoI legislation, namely openness and accountability of governments and the

individual's right to privacy.[613]

Delays and cost of accessing records

9.86

The Committee received evidence of delays in the

provision of files for access, particularly for people living in country and

regional areas. One witness stated:

It is not always so easy finding out about yourself. DOCS took

three months to pull my file and another two weeks to copy the information I

requested. (Sub 241)

9.87

Relationships Australia

commented that some people had to wait years to access their files:

This morning I had a phone call from someone who has asked for

their records in southern New South Wales.

It has taken two months for them to get to the office, and now they have to

wait because there is no-one available to actually go through the records with

them as they are too busy. This is a common story told to us.[614]

9.88

Witnesses also considered that having to pay for access

to their personal information was demeaning and insulting.

Even though it may be possible that the early files on us may

have been destroyed, I find it very hard to believe as there are a few words

about me which I acquired from FOI on request for which I was charged $15.[615]

I was sent firstly to Ashfield Babies Home for approximately one

year - I don't know the exact details as I resent paying $50 for my 'records'

to discover that there are no details as to who I was, only that I was there -

and I know that already. (Sub 418)

It is our information. We should not be putting our hands into

our pockets at all. The government should be assisting us in every possible way

for education, for psychological reasons, for medical reasons and for finding

our personal information. That is the least they could do in assisting us.[616]

9.89

While many types of government records may be of

interest to care leavers, they are expensive to access. For example, CLAN noted

that many people who grew up in care went into the adult gaol system. Those

wanting to access their prison records must pay $30 (or $15 if they are on a

pension). CLAN also commented that many children became state wards because

their parents failed or could not afford to pay the fees for their children in

the care of the government or churches. As a consequence, many parents were

sent to prison for failure to pay fees. In these cases, state wards are looking

for information on their parents as well: 'if their parents were sent to prison

it helps us to understand why our parents didn't visit us in the Homes for years

and years'.[617]

Overcoming problems of access

9.90

The Benevolent Society's Post Adoption Resource Centre

outlined succinctly the needs of those seeking access to records:

Care leavers need to have access, free of charge, to all file

information held by a service provider, that relates to themselves and the

reasons for their admission to care irrespective of their legal status at the

time of their placement. They should also have copies of file material and

original documents. They should have detailed specific information about all

members of their family.

...It is essential that a sympathetic, experienced and suitably

qualified person is available at the time of reading the file. It should also

be ensured that there is a limited delay in the files becoming available. In

the case of non-government past providers, there should be flexibility as to

when and where the file is accessed, taking into consideration the care

leaver’s possible strong feelings about returning to the buildings associated

with their experience in care.[618]

9.91

CBERSS commented on the benefits of easy access to

records:

Quick and easy access to records about their own childhood is an

important part of the healing process for CBERSS clients, as it would be for

most people whose family ties were broken or damaged as children.[619]

9.92

A number of suggestions were made in evidence to achieve

better access to files and improve services for those searching for families.

CLAN recommended the establishment of dedicated information and search services

in all States specifically targeted to state wards and Home children to help

locate family members and their own history. These services should include:

-

Assistance with accessing their file(s), i.e.

dealing with government or agency authorities. This is often a very daunting

task for a Care Leaver: it is the first step to acknowledging what happened to

them and there is often also apprehension about what the file will contain.

-

Mediation with the agency which raised them as many

people are reluctant to approach the agency, where in their opinion it failed

in its duty of care, or allowed abuse to occur.

-

Support in reading the file from somebody

familiar with the attitudes and practices of the past care system.

-

Meetings and/or mediation with persons

identified from the file, for example a sibling or ex-carer. Support and

facilitation services may be essential for people who wish to meet with and

challenge ex-carers about issues still affecting them today. This is an option

that should be available for Care Leavers who wish to have some closure with

their past.[620]

9.93

CLAN also recommended that research be carried

out to search for and locate records, collate histories of care locations, and

perhaps establish a centralised records service for care leavers. CLAN stated

that this is a fragmented history whose pieces must be pulled together as an

important part of Australia’s

social history. In addition, all States should follow the lead of New

South Wales and publish directories similar to Connecting Kin: A Guide to Records.

This was also supported by other witnesses.[621]

9.94

CLAN recommended that funds

should be allocated to advertising nationally for records since in some cases

records have simply ended up in agency basements or in an individual's spare

room. CLAN noted that poor record-keeping combined with the incomplete

retention of records by many organisations means that resources need to be

allocated for proactive record searching to help fill in the gaps. Proactive

searching may well turn up many more 'lost' or forgotten records than those

currently available.[622]

9.95

Other organisations also recommended that each State

government appoint officers in the relevant agencies to have the sole

responsibility for the needs of care leavers.[623]

9.96

As noted earlier, a major concern for both agencies and

those seeking to access records is the preservation of records as many are old

and in poor condition. Preserving, indexing and ensuring easy access to records

is expensive and time consuming. Mercy Community Services recommended that the

Commonwealth Government provide funding to allow past providers of

institutional care to preserve, index and image their remaining records, as a

service for past residents.[624]

9.97

The Committee, in its report on child migrants, found

that access to records was of fundamental importance to those who were

searching for their families. The Committee made recommendations to improve