Chapter 3 - Poverty and Inequality in Australia

The existing and growing gap between the rich and the poor in

Australia is obvious to even the most ardent of sceptics.[1]

3.1

This chapter provides an overview of the nature and extent of poverty in

Australia. It provides a discussion of the origins of poverty research in Australia,

especially the work of Professor Henderson beginning in the 1960s. The chapter

then analyses recent statistics related to poverty and inequality in Australia,

including an overview of the groups most at risk of being in poverty today and

recent studies of income and wealth distribution.

The origins of poverty research

3.2

The first systematic attempt to estimate the extent of poverty in Australia

was undertaken in the mid-1960s by researchers at the Melbourne University's Institute

of Applied Economic and Social Research (IAESR). The research team, led by

IAESR Director Professor Ronald Henderson, conducted a survey of living

conditions in Melbourne and estimated the extent of poverty in Melbourne using

a poverty line based on a two-adult, two-child family set at an income equal to

the value of the basic wage plus child endowment payments. The study found that

one in sixteen of Melbourne's population was living in poverty in 1966.

3.3

The poverty benchmark in this study was chosen because of its relevance

to Australian concepts of the minimum income, and also because as a proportion

of average earnings it was similar to poverty lines used in other countries. It

was regarded by the research team as an austere measure, likely to produce

lower-bound estimates of poverty. The equivalence scale used to derive poverty

lines for other family types was, in the absence of any reliable Australian

estimates of relative needs, derived from a survey of household budgets and

costs undertaken in New York in the 1950s.

The Henderson Commission of Inquiry

3.4

Community and political pressure following the release of the 1966

survey into poverty in Melbourne led to calls for a national inquiry to

determine whether the problems highlighted in this study applied to the nation

as a whole. A Commission of Inquiry into Poverty was established in August 1972

by the Prime Minister, Mr McMahon. Professor Henderson was appointed as

Chairman of the inquiry (the inquiry was subsequently referred to as the

Henderson Inquiry). After the 1972 election the new Prime Minister, Mr Whitlam,

expanded the Commission's size and scope with specific responsibility to focus

on the extent of poverty and the groups most at risk of experiencing poverty;

the income needs of people in poverty; and issues related to housing and

welfare services. These topics were addressed in the Commission's first main

report, Poverty in Australia, released in August 1975.

3.5

The poverty line described above was subsequently used by the Henderson

Inquiry to produce the first authoritative estimates of poverty in Australia.

The information on poverty was based on data from an ABS income survey

undertaken in August 1973. The report's main focus was on identifying the

extent of poverty due to inadequate income, in the sense of being low income

relative to need. The income unit chosen was a married (or defacto) couple or

single person, with or without dependent children. A unique feature of the Henderson

poverty line was that it allowed poverty to be estimated both before and after

housing costs. After-housing costs were derived by deducting actual housing

costs from income and comparing the remaining income with a poverty line that

excluded the housing cost component.[2]

3.6

The Henderson Commission's main findings were as follows:

- Over 10 per cent of income units in 1972-73 were below the

Commission's poverty line. A further 8 per cent were defined as 'rather poor',

having an income of less than 20 per cent above that line.

- About 7 per cent of income units were below the poverty line

after housing costs were taken into account. Those renting from private

landlords were the poorest group.

- About three-quarters of those below the poverty line (before

housing) were not in the workforce.

- Overall, female sole parent families comprised the largest

proportion of very poor people.

- About one-third of the single aged were very poor before housing.

However, less than 10 percent were very poor after housing, because a large

number were home-owners.

- The group with the largest percentage gap between its income and

the poverty line comprised large families on wages on or just above the minimum

wage.

- There was significantly more poverty in rural areas on a before

housing basis. After housing, however, the difference was not as significant.

- Very few young men were voluntarily unemployed and thus below the

poverty line.[3]

Extent of poverty in Australia

3.7

There have been a number of recent studies that have attempted to

estimate the extent of poverty in Australia; however, these estimates vary

widely. Submissions to the inquiry, often drawing on these studies, have also

presented a range of estimates. A number of recent poverty estimates are

presented in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Poverty in Australia

– Selected Estimates

|

|

Year

|

Numbers in poverty

|

|

Henderson poverty line1

|

1999

|

3.7 – 4.1 million (20.5

– 22.6% of population)

|

|

St Vincent de Paul

Society2

|

-

|

3 million

|

|

Australian Council of

Social Service3

|

2000

|

2.5 – 3.5 million (13.5

– 19% of population)

|

|

The Smith Family4

|

2000

|

2.4 million (13 % of

population)

|

|

Brotherhood of St

Laurence5

|

2000

|

1.5 million

|

|

The Australia

Institute6

|

-

|

5 – 10% of population

|

|

Centre

for Independent Studies7

|

-

|

5%

of population in 'chronic poverty'

|

Sources:

1 Cited in Harding A

& Szukalska A, Financial Disadvantage in Australia – 1999, The Smith Family,

2000, p.38.

2

Submission

44, p.44 (SVDP National Council).

3

Submission

163, p.9 (ACOSS).

4

Harding

A, Lloyd R & Greenwell H, Financial Disadvantage in Australia –

1990 to 2000, The Smith Family, 2001, pp.5, 22-23.

5

Submission

98, p.3 (BSL).

6

Committee

Hansard

19.6.03, p.648 (The Australia Institute).

7

Submission

45, p.10 (CIS).

3.8

The table shows that the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS) has

estimated that 5 per cent of the population can be considered to be in 'chronic

poverty'.[4]

Other estimates are much higher. The Smith Family has estimated that 13 per

cent of the population was in poverty in 2000 – this had increased from 11.3

per cent since 1990.[5]

Poverty rates based on the Henderson poverty line estimate that 20.5 per cent

of the population was in poverty (after paying for housing costs) or 22.6 per

cent in poverty (before housing costs) in 1999.[6]

A study by King found that in 1996, 16.7 per cent of income units were below

the poverty line and very poor, with a further 13.7 per cent classified as 'rather

poor'.[7]

3.9

The CIS estimate of 5 per cent of the population in chronic, long term

poverty is based on a number of assumptions. These assumptions include that

half to two-thirds of those below the poverty line at any one time are

transitional; perhaps half or more are under-reporting their true income; and

including the value of government services would raise the final incomes of

lower income groups by about 50 per cent. The CIS, however, provides little quantifiable

data to support their claims and concede that their estimate of those in

poverty is a 'guesstimate'.[8]

3.10 By contrast, as

noted above, poverty rates based on the Henderson poverty line have reported

much higher estimates of poverty – up to 23 per cent of the population. Serious

concerns have been raised over how this poverty line has been updated over time

to account for changes in community incomes. It has been argued by some

researchers that updating this poverty line by increases in seasonally adjusted

household disposable income per capita grossly inflates the poverty estimates.

The Smith Family has argued that the Henderson poverty line produces a picture

of an 'ever-rising tide' of poverty because it is set at an ever-increasing

proportion of family income.[9]

3.11 ACOSS stated

that depending on the poverty lines used and taking into account housing costs

there are between 2.5 million (13.5 per cent) and 3.5 million people (19 per

cent) living in poverty in 2000, with between 800 000 and 1.3 million children

in poverty.[10]

The Brotherhood of St Laurence (BSL) estimated that even by the most cautious

estimate (using the half median income measure) more than 1.5 million people

were living below the poverty line in 2000 – 'whichever way it is measured,

this is simply too high for a wealthy country like Australia'.[11]

The SVDP National Council stated that in Australia today approximately 3

million people are poor – and 'further to this, our nation is torn by

inequality'.[12]

3.12 Recent studies

commissioned by the Smith Family on poverty in Australia have generally

reported poverty estimates midway between the figures produced by the CIS and

the Henderson poverty line. One report, Financial Disadvantage in Australia

– 1999, found that in 1999:

- One in seven Australians or 2.4 million people lived in poverty,

when the poverty line is set at half the average family income of all

Australians.

- Income poverty had declined slightly since the 1980s – 13.3 per

cent of Australians were in poverty in 1999, compared with 14.6 per cent in

1982.

- While there was a slight decline in poverty among adults during

this period, the major factor underlying this fall was a 20 per cent fall in

the poverty rate among dependent children.

- Aged persons – of all poor Australians, only nine per cent live

in a family headed by a person aged 65 years or more. On an after-housing

basis, only six per cent of all poor Australians live in households headed by

an aged person.

- Poverty mainly affects those of working age – almost one-third of

those in poverty live in families where the head is not in the labour force,

while over one quarter are in families where the head is unemployed.

- While more than half of all Australians in poverty live in

families with no adult earners, over 40 percent live in families where one or

both adults in the family works. About one-fifth of all those in poverty live

in families where both parents work.

-

Just over one half of all of Australia's poor live in families

whose main income source is government cash benefits.

-

About half of all poor people in Australia live in families that

contain children. Children living in sole parent and larger families continue

to face high poverty risks.[13]

3.13 The report

defined 'financial disadvantage' or 'poverty' in terms of a family whose income

is less than half the average family income. The study justified its use of the

'half average income' poverty line arguing that it better captures relative

deprivation in times of rising income inequality than using a figure based on

median incomes. As the top income earners become better off, then the poor are

relatively worse off. That is, they are poorer in relative terms. Using the 'half

average income' poverty line denotes acceptance of the proposition that the

living standards of the poor should be measured against the living standards of

all the population, including the very affluent.[14]

The data source for the study was the 1997-98 ABS national income survey,

updated to May 1999. Income in the study included wages and salaries, workers

compensation and superannuation, dividends and rents, income from self-

employment and child support payments.

3.14 Another study

commissioned by the Smith Family, Financial Disadvantage in Australia – 1990

to 2000, examined trends in poverty in Australia during the 1990s. The data

sources for this study were various ABS national income surveys conducted over

the 1990s. Poverty estimates based on this study are summarised in Table 3.2.

The study also contains a large collection of other data on poverty in Australia.

Table

3.2: The Smith Family – Estimated Poverty Rates 1990-2000

| (percentage of population) |

| 1990 |

1995 |

1996 |

1998 |

2000 |

|

| 11.3 |

11.7 |

12.0 |

12.6 |

13.0 |

(a) |

| 8.2 |

8.2 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

8.7 |

(b) |

- half average income poverty line

- half median income poverty line

Source: Harding A,

Lloyd R & Greenwell H, Financial Disadvantage in Australia

1990-2000, The Smith Family, 2001,

p.5.

3.15 The table shows

that poverty increased from 11.3 per cent to 13 per cent of the population over

the period from 1990 to 2000, when the poverty line is set at half the average

family income of all Australians (the study's preferred measure). In 2000

almost one in eight Australians or 2.4 million people lived in poverty. The

study pointed to the persistence of poverty despite a decade of economic

growth. The report noted that 'strong economic growth over the past decade has

not produced comparably strong social outcomes for many different groups within

Australia'.[15]

3.16 The data shows

that estimated poverty rates are sensitive to the poverty line used. As

previously noted, the Smith Family studies justify their use of the 'half

average income' poverty line on the grounds that it better captures relative

deprivation in times of increasing income inequality.[16]

3.17 The other main

findings of the study are detailed below.

- Poverty among adults increased steadily during the decade.

- Child poverty fell during the first half of the 1990s but

increased since that time.

- There was an increase in the poverty risk faced by families

dependent on government cash benefits, which increased from 24 per cent in

1990 to 31 per cent in 2000. As a result of this shift, by 2000 government

cash benefits were the main family income source for about 60 per cent of

poor Australians – up from 46 per cent in 1990.

- Unemployment was a key generator of poverty – about half of all

Australians aged 15 years and over who were unemployed lived in poverty.

Poverty increased among the unemployed in the late 1990s.

- The proportion of poor families that had wages and salaries as

their primary income source remained unchanged over the 1990s. Having a job

appeared less of a protection against poverty than in the past, with the risk

of being in poverty among all Australians aged 15 years and over and working

part time rising from 10.7 per cent in 1990 to 11.7 per cent in 2000.

Part-time work appeared to be associated with greater vulnerability to poverty

than having full-time work. For the vast majority of wage and salary earner

families, having a full time job was sufficient to ensure that the family was

not in poverty.

- The poverty rate for men was slightly higher than the poverty

rate for women, with the somewhat higher number of sole parents and older women

in poverty being offset by the large number of single men and men aged between

15 and 64 years in poverty.

- Poverty rates generally decrease with age, although for a large

part of the decade poverty among those in the 50 to 64 year age bracket was

higher than for people aged 25 to 49 or over 65 years.

- A major change during the decade has been the steady increase in

poverty rates among the aged. While the risk of being in poverty was previously

much lower for the aged than for those of workforce age, now the risk is

relatively similar. However, if poverty is assessed after housing costs have

been met a different picture emerges. For the aged, due to their high home

ownership rates, the risk of being in poverty did not change during the 1990s.

Conversely, poverty among adults aged 25 to 44 years has become more serious,

with almost one-fifth of adults aged 25 to 44 years in poverty on an

after-housing basis.

- The results by State fluctuate, and it is not clear whether the

year-to-year changes reflect real variation or sampling error for the smaller

States. NSW had the highest poverty rate in 2000, with 13.9 per cent of its

residents in poverty. Poverty also increased in the other States, with only Queensland

and Tasmania remaining relatively unchanged.

- The depth of poverty did not change greatly during the 1990s,

with the average gap between a poor family's income and the poverty line increasing

from $112 in 1990 to $118 in 2000 (after accounting for the impact of

inflation).[17]

3.18 The Centre for

Independent Studies has criticised the above Smith Family study into poverty

trends arguing that the extent and nature of poverty identified in the study

has been exaggerated.

3.19 The CIS has

three main criticisms of the study, namely:

- The study has confused poverty and inequality by adopting a

relative view of poverty, whereas most people think of poverty in absolute

terms.

- By adopting a poverty line based on mean (average) rather than

median income the study has exaggerated the extent of poverty in Australia.

- The ABS data on which the study relies are not sufficiently

reliable for conclusions to be drawn about the extent of poverty. The problems

include under-reporting of incomes especially by welfare recipients and the

self employed and the exclusion of certain sources of income, such as income in

kind and government benefits provided below cost.[18]

3.20 These arguments

have been disputed by Professor Peter Saunders of the Social Policy Research

Centre. In relation to the first argument, he has argued that while most people

think of poverty in subsistence terms, this is not the same as supporting an

absolute definition of poverty. A subsistence notion of poverty emphasises that

poverty is a situation where basic needs cannot be met, but this is consistent

with the goods and services that are required to meet those needs being defined

relatively – in the sense that they will depend on the general lifestyles,

living standards and values of the community at a particular point in time.

3.21 In regard to the

second point, Professor Saunders argues that neither the mean nor median income

alone provides information about how well needs are being met, although the

mean is preferred by some researchers because it better captures relative

deprivation in times of rising income inequality. He did concede, however, that

most poverty researchers prefer to link poverty lines to median income rather

than mean income. In relation to the third CIS argument, he argues that while

the ABS data may be unreliable there is no reliable research to support that

claim. He also argues that it is not clear what impact the inclusion of many

subsidised services would have on the distribution of income.[19]

Who is in poverty today?

3.22 Evidence to the

Committee and a range of studies into poverty and deprivation has shown that

poverty is more likely to occur among particular groups in the population.[20]

The major groups are identified in the table below and include Indigenous

Australians, the unemployed and people dependent on social security benefits.

This is not an exclusive list of those groups experiencing poverty, but serves

to identify those most commonly referred to in studies into poverty and

evidence received during the inquiry. Further discussion of poverty and

disadvantage among these groups and others is contained in later chapters of

the report.

Groups at high risk of

poverty

-

Indigenous Australians

-

people who are unemployed

-

people dependent on government

cash benefits

-

sole parent families and their

children

-

families that have three or more

children

-

people earning low wages

-

people with disabilities or those

experiencing a long term illness

-

aged people, especially those

renting privately

-

young people, especially in low

income households

-

single people on low incomes

-

people who are homeless

-

migrants and refugees.

3.23

A study by the Smith Family/NATSEM has illustrated the distribution of

poverty as indicated in the table below.[21]

Who is poor in Australia?

A Smith Family study estimated that of every 100 poor

Australians:

-

24 live in working-poor (wage and

salary) families;

-

23 live in families with an

unemployed head;

-

15 live in other families

dependent on social security;

-

14 live in sole parent families;

-

9 live in self-employed families;

-

6 live in families headed by an

aged person;

-

5 live in some other type of

family; and

-

4 live in families reliant on

superannuation and investment income.

3.24

Indigenous Australians face a far greater risk of poverty than other

Australians, and is indicated in high levels of joblessness, low levels of

formal education, poor health, inadequate housing and the experience of

dispossession and racism.[22]

The nature and extent of poverty among Indigenous people is discussed in

chapter 13.

3.25 In addition to

the groups listed above, other smaller population groups are also vulnerable to

poverty including people with drug and alcohol problems; domestic violence

survivors; people living in caravan parks; people with caring responsibilities,

including young carers; problem gamblers; recently released prisoners and some

groups whose poverty remains undocumented in any substantial way (for example

mentally ill people).[23]

One submission noted that while vulnerability to poverty occurs amongst broad

population groups it is likely that smaller population groups can experience

high levels of economic hardship where low incomes are compounded by quite

specific forms of disadvantage.[24]

3.26 Poverty is

increasingly associated with low pay. The Australian Liquor, Hospitality and

Miscellaneous Workers Union (LHMU) noted that the crisis of low pay contributes

strongly to poverty as low paid workers are often also the 'jobless poor'. Low-paid

workers tend to 'churn' through a series of low-paid jobs interspersed with

periods of unemployment – as such the unemployed and the low paid are often the

same people at different times. In addition, a large proportion of poor people

live in households with a wage earner (the wages of the low paid thus support

the poor); people who earn low pay are generally found in households which have

a low income; and low paid workers become retires – low wages project

disadvantage into the future, because low paid workers cannot adequately save

for their retirement.[25]

3.27 Poverty is also

associated with where people live. There is growing evidence of regional

disparities, with geographic concentrations of great wealth and great

disadvantage within areas of all major capital cities and between cities and

rural areas.[26]

Poverty in rural and regional communities is discussed in chapter 14.

Poverty by State/Territory

3.28 The extent of

poverty varies between the States and Territories with evidence indicating that

the smaller, less populous States generally exhibit the highest incidence of

poverty and deprivation (although the extent of poverty often varies depending

on the indicator used). Table 3.3 reproduces Smith Family data on poverty

levels in the States.

Table 3.3: Poverty levels – States and Territories (1999)a

|

|

NSW

|

VIC

|

QLD

|

SA

|

WA

|

TAS

|

NT

|

ACT

|

|

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

|

Before

housing costs

|

14.1

|

12.3

|

12.9

|

15.9

|

12.4

|

15.4

|

8.9

|

8.9

|

|

After

housing costs

|

18.1

|

15.5

|

18.6

|

18.9

|

16.2

|

18.7

|

12.4

|

12.4

|

a half

average income poverty line.

Source: Harding A & Szukalska A, Financial Disadvantage in Australia

– 1999, The Smith Family, 2000, p.17.

3.29 As the table

shows, poverty levels (on a before-housing cost basis) were greatest in South

Australia, Tasmania and NSW. Poverty levels in all the States and Territories

increased after housing costs were taken into account, although the pattern of

poverty across the States was similar. South Australia, Tasmania and Queensland

had the highest proportion of people in poverty after housing costs are

removed, while the lowest proportion was recorded in the ACT and the Northern

Territory (12.4 per cent).

3.30 ABS data show

that, in 2001, the proportion of people in 'low income' households (before

housing costs) was highest in Tasmania (27 per cent) and the Northern Territory

(25 per cent), and lowest in the ACT (11 per cent).[27]

ABS data for 2000-01 indicate that average levels of incomes varied between the

States. Three States had disposable household incomes below the national

average of $469 per week. Tasmania was the poorest State with mean weekly

income 17 per cent below the national average income level, followed by South

Australia (9 per cent below) and Queensland (6 per cent below). NSW and Victoria

both recorded incomes at 3 per cent above the national average, with Western

Australia at about the national level. The ACT recording the second highest

average income (24 per cent above the average) after the Northern Territory.[28]

3.31 Submissions and

witnesses commented on the particular features of poverty in the various

States. SACOSS noted that South Australia is a low income state with average

(mean) incomes, on both a before and after-housing basis, the lowest in the

country. High levels of poverty have been contained by the State's lower

housing costs, although this is now at risk due to a reduction in the public

housing stock.[29]

SACOSS stated, however, that the rate of poverty has doubled since the early

1980s. Rates of inequality have also doubled, but South Australia is less

unequal than the other States, which is partly due to the fact that it has

fewer high-income earners.[30]

3.32 Tasmania, like South

Australia, is a low income State, with high levels of unemployment (and low

labour force participation), low rates of pay for those employed and high

levels of part-time and casual employment. Tasmania is also a high-cost state

in terms of the 'basket' of essential goods and services required by all

households, such as food, energy and transport.[31]

Sea freight and transport charges can increase the cost of consumables relative

to those on the mainland.[32]

A further indicator of disadvantage is the high take-up of welfare payments –

some 40 per cent of Tasmanian income units rely on government pensions and

allowances.[33]

3.33 In Western

Australia, WACOSS pointed to growing levels of deprivation within the

community, noting that it is the most geographically vast and isolated State in

the country and 'faces unique and complex issues' in relation to poverty,

especially related to its remoteness, high living costs and the problem of

poverty amongst Indigenous communities.[34]

3.34 In Queensland

the geographical differences in poverty and disadvantage were highlighted.

Submissions and other evidence noted that poverty is particularly concentrated

in a number of regions such as parts of the Cape and Gulf regions – both areas

with large Indigenous populations, certain regional centres and areas on the

urban fringe.[35]

QCOSS indicated that poverty in Queensland has risen steadily from the 1980s to

the mid 1990s, with poverty rates almost doubling during that period – 'of

great concern is that poverty rates in Queensland have been and continue to be

consistently high in comparison with national rates and in comparison with

other states and territories'.[36]

3.35 In Victoria,

VCOSS pointed to the growing disparity in income levels between regional/rural

areas and metropolitan areas and specific areas within metropolitan centres.[37]

3.36 In the Northern

Territory, NTCOSS indicated that the level of poverty in the Territory is

often hidden and that on all indicators the Territory has the highest level of

poverty of any State or Territory. NTCOSS commented that poverty is influenced

by remoteness, a large Indigenous population, geographical distances with a

small population spread over a large area and high population mobility which

poses challenges in providing adequate physical and social infrastructure.

These factors also impose additional costs for those living in the Territory.[38]

Income inequality

3.37 Studies into

trends in income inequality over recent decades and submissions to the inquiry

point to increasing income inequality in Australia. As the Salvation Army noted

'strong economic growth over the last decade has not resulted in the highly

anticipated emergence of strong social outcomes for many Australians'.[39]

3.38 Studies into the

distribution of both earnings and of income have shown increasing

inequality. In relation to earnings, studies have found increasing inequality since

the 1980s. An ABS study concluded that inequality in the distribution of wage

and salary earnings of full-time adult employees increased in the 1980s and

that this trend continued through the 1990s.[40]

Another study by Professor Saunders found that the inequality in full-time wage

and salary earners incomes, as measured by the Gini coefficient, increased from

0.224 in 1990, to 0.271 in 1994-95 to 0.275 in 1999-2000.[41]

Analysis by FaCS confirmed these trends. The Department stated that there has

been increasing dispersion of earnings since 1979, with the top percentiles

recording stronger growth than the bottom percentiles. Since the mid 1980s

three trends were evident:

- between 1985 and 1990, earnings at the bottom fell almost

continuously in real terms, while those at the top remained stable after an

initial fall;

- between 1990 and 1996, earnings at the bottom initially rose, but

then remained stable, while those at the top consistently increased in real

terms; and

- between 1996 and 2000 earnings grew at all points, although more

rapidly at the top of the earnings distribution.[42]

3.39 Earnings

distribution statistics reflect the impact of the market on the distribution of

economic rewards. A more complete picture is provided by taking into account

the impact of government tax and transfer (social security) programs. By

assessing the impact of these programs it is possible to determine the

distributional impact of social security benefits and the impact of income taxes

on the distribution of income.

3.40 As noted above,

income distribution statistics, which take into account the impact of the

tax-transfer system, show a trend towards increasing inequality in Australia.

This is indicated in recent ABS statistics as detailed in Table 3.4.[43]

3.41 As the table

shows, one measure of the spread of incomes across the population is indicated

by the percentile ratios. The P90/P10 ratio shows that in 2000-01, the top 10

per cent of households received 3.97 times the income of the bottom 10 per

cent. This ratio has increased from 3.77 in 1994-95, thus showing increasing

inequality over the period 1994-95 to 2000-01.

[44]

Table 3.4: Selected Income

Distribution Indicators*

|

|

1994-95

|

1995-96

|

1996-97

|

1997-98

|

1999-2000

|

2000-01

|

|

Ratios of incomes of households at top of selected

income percentiles

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

P90/P10 ratio

|

3.77

|

3.74

|

3.66

|

3.77

|

3.89

|

3.97

|

|

P80/P20 ratio

|

2.56

|

2.58

|

2.54

|

2.56

|

2.64

|

2.63

|

|

P80/P50 ratio

|

1.55

|

1.57

|

1.56

|

1.56

|

1.57

|

1.56

|

|

P20/P50 ratio

|

0.61

|

0.61

|

0.61

|

0.61

|

0.59

|

0.59

|

|

Income share

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lowest quintile %

|

7.9

|

8.1

|

8.3

|

7.9

|

7.7

|

7.6

|

|

Second quintile %

|

12.8

|

13.0

|

13.1

|

12.8

|

12.6

|

12.5

|

|

Third quintile %

|

17.7

|

17.7

|

17.8

|

17.6

|

17.6

|

17.7

|

|

Fourth quintile %

|

23.7

|

23.9

|

23.7

|

23.8

|

23.7

|

23.6

|

|

Highest quintile %

|

37.8

|

37.3

|

37.1

|

37.9

|

38.4

|

38.5

|

|

All

persons %

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

|

Percentage share of total income received by persons

with:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Low income (a) %

|

10.8

|

10.9

|

11.0

|

10.8

|

10.5

|

10.5

|

|

Middle income (b) %

|

17.7

|

17.7

|

17.8

|

17.6

|

17.6

|

17.7

|

|

High income (c) %

|

37.8

|

37.3

|

37.1

|

37.9

|

38.4

|

38.5

|

|

Gini

coefficient no.

|

0.302

|

0.296

|

0.292

|

0.303

|

0.310

|

0.311

|

* Equivalised disposable household income – disposable

household income adjusted on the basis of the household's size and composition.

- Persons

in the second and third income deciles.

- Persons

in the middle income quintile.

- Persons

in the highest income quintile.

Source:

ABS, Household Income and Income

Distribution, Cat. No.6523.0, July 2003, pp.10, 13.

3.42 Another measure

of income distribution is provided in the income shares going to groups of

people at different points in the income distribution. The table shows that, in

2000-01, those on 'low incomes' (that is, 20 per cent of the population in the

2nd and 3rd income deciles) received 10.5 per cent of

household income, whereas those in the 'high income' group (that is, the 20 per

cent of the population in the highest income quintile) received 38.5 per cent

of the income.[45]

The income shares of the low income group declined from 10.8 per cent to 10.5

percent of income over the period 1994-95 to 2000-01, whereas the income share

of the high income group increased from 37.8 to 38.5 per cent over the same

period. The 'middle income' group's share of income remained relatively stable.

The ABS concluded that its analysis of the latest income distribution statistics

support 'a conclusion of some increase in inequality' since 1994-95.[46]

3.43 Professor Saunders,

commenting on the ABS data, noted that since 1995-96, 47 per cent of the

total increase in income was received by those in the top quintile. He added

that 'almost half of the economy-wide increase in income generated by economic

growth under the Howard Government was of no benefit to the bottom four-fifths

of the population'.[47]

3.44 An earlier study

by Harding and Greenwell reflected these trends. The study based on ABS income

surveys found that income inequality increased between the late 1980s and the

mid-1990s and there was some evidence to suggest that this trend had continued

(which was confirmed in the ABS study cited). The increase in inequality was

driven by declines in the income shares of the bottom 10 per cent, and to a

lesser extent, the middle 20 per cent of Australians during the 1990s, and an

increase in the income share of the top 10 per cent.[48]

3.45

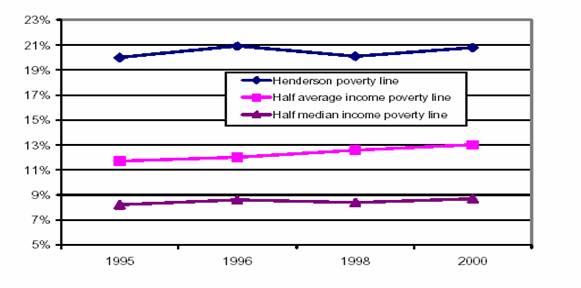

This trend towards increasing inequality was reinforced in evidence from

ACOSS. Drawing on Smith Family research, ACOSS noted that using three different

poverty lines 'all three show a gradual but significant increase in income poverty

over the late 1990s'. This is illustrated in Figure 3.1.[49]

Figure

3.1: Trends in income poverty

3.46 Not only are

income levels low for large numbers of Australians but critical expenditures on

a range of necessities have been rising at a faster rate than the level of

inflation. For example, Table 3.5 shows that since 1989-1990 the following

costs have increased.

Table 3.5: Cost Increases

|

Education

|

|

An Increase of 173 % higher

than the increase in the CPI

|

|

Health

|

|

An Increase of 98 % higher than

the increase in the CPI

|

|

Hospital

and medical

|

|

An Increase of 137 % higher

than the increase in the CPI

|

|

Dental

|

|

An Increase of 113. 5 % higher

than the increase in the CPI

|

|

Urban

Transport Fares

|

|

An Increase of 134 % higher

than the increase in the CPI

|

Source: Submission 44, p.19 (SVDP National Council).

Impact of the GST

3.47 Submissions

commented on the adverse financial impact that the GST is having on low income

groups. They noted that the costs for many products and services have

substantially increased since the introduction of the GST, especially in

relation to clothing and other necessities, utility prices, insurance, and

household services including repairs and maintenance. It was commented on that

the compensation arrangements in relation to tax cuts and pension increases for

low income households when the GST was introduced has been inadequate.[50]

3.48 FaCS advised the

Committee that information on the distributional impact of the GST on different

income groups will not be available until the release of data from the 2003-04

ABS Household Income and Expenditure Survey. This data will not be available

until late 2005.[51]

Impact of taxes, transfers and

other benefits

3.49 Studies have

shown that the trend towards increasing earnings dispersion, in particular, has

been mitigated by the redistributive impact of taxes and transfer (social

security) payments and other benefits. One study noted that in 1999-2000, for

example, social transfers reduced income inequality (as measured by the Gini

coefficient) by 22.2 per cent, while income taxes reduced it by an additional

12.1 per cent. In that year, the two main distributive instruments of the

welfare state combined to reduce income inequality generated in the market

sector by around one-third.[52]

3.50 A comprehensive

study in the Smith Family submission showed the redistributive effect of taxes,

transfers and indirect benefits. The study looked at the impact of government

cash transfers (such as pensions), income taxes, selected indirect taxes and

indirect benefits, such as health, education, housing and welfare. This study

is particularly valuable as previous studies referred to above generally exclude

the impact of indirect taxes and indirect benefits. Details of the study are

provided in Table 3.6.

3.51 The study shows

that direct cash benefits, such as the age pension and unemployment allowances,

are heavily skewed towards lower income groups. Indirect benefits, via the use

of free or subsidised social services, are also skewed towards lower income

groups but are not nearly as targeted towards lower income groups as the direct

cash benefits. In particular, the second lowest and middle income quintiles

receive higher indirect benefits than the lowest income quintile.

Table 3.6: Estimated average

value of benefits received and taxes paid by equivalent income quintile,

1998-99a

|

|

Quintile

of Equivalent Disposable Income

|

|

|

Bottom

|

Next

|

Middle

|

Next

|

Top

|

All

|

|

|

20%

|

20%

|

20%

|

20%

|

20%

|

20%

|

|

|

$ pw

|

$ pw

|

$ pw

|

$ pw

|

$ pw

|

$ pw

|

|

Direct cash benefitsb

|

252.3

|

202.4

|

68.8

|

25.5

|

6.5

|

111.0

|

|

Gross

income

|

233.6

|

440.4

|

787.4

|

1132.2

|

1826.7

|

884.8

|

|

Disposable income

|

232.7

|

418.2

|

666.3

|

899.8

|

1311.9

|

706.3

|

|

Selected

indirect benefits

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

-

Education

|

43.5

|

85.8

|

106.8

|

81.0

|

51.0

|

73.6

|

|

-

Health

|

92.8

|

106.2

|

87.6

|

74.0

|

61.8

|

84.4

|

|

-

Welfare

|

49.3

|

45.6

|

26.4

|

12.1

|

2.3

|

27.1

|

|

-

Housing

|

12.6

|

3.4

|

1.0

|

0.4

|

0.2

|

3.5

|

|

Total

indirect benefits

|

198.3

|

241.0

|

221.8

|

167.5

|

115.3

|

188.7

|

|

Disposable income + indirect benefits

|

431.0

|

659.2

|

888.0

|

1067.3

|

1427.2

|

895.0

|

|

Selected

indirect taxes

|

38.8

|

60.8

|

86.1

|

95.4

|

114.7

|

79.2

|

|

Final

income

|

392.2

|

598.3

|

802.0

|

971.9

|

1312.5

|

815.8

|

|

Ratio of final income to disposable

income

|

1.7

|

1.5

|

1.2

|

1.1

|

1.0

|

1.2

|

|

Average number of usual residents

|

2.0

|

2.7

|

3.1

|

2.8

|

2.4

|

2.6

|

a Disposable

income equals gross income minus income tax. Final income equals disposable

income plus indirect benefits minus indirect taxes.

b For

low-income households average cash benefits are higher than gross income

because some households have negative private incomes (eg small businesses with

losses).

Source:

Submission 172, p.36 (The Smith

Family).

3.52 The impact of

selected indirect taxes including petroleum, alcohol and tobacco taxes is also

included in the study. Such taxes are regressive, taking a greater proportion

of the income of low income households than of high-income households. Indirect

taxes paid by low-income households, for example, amount to an estimated $38.80

per week – or just under 17 per cent of disposable income. For high income

households, indirect taxes are much higher at $114.70 per week, but this

represents only 14 per cent of disposable income. 'Final income' in the study

refers to private earnings, social security cash payments, indirect benefits

such as education and health and the impact of indirect and income taxes. As

the table indicates, low income households are net beneficiaries from these

indirect benefits and taxes, with such indirect benefits and taxes increasing

final income by 70 per cent relative to disposable income. For high income

households, indirect taxes paid cancel out indirect benefits received, leaving

their disposable and final income at the same level. The study shows that the

incomes of low-income households are significantly raised after taking into

account taxes and benefits.[53]

Wealth distribution

3.53 Wealth plays an

important role in generating well-being. Not only do assets, such as

investments, generate income for households, but others, such as owner-occupied

housing, provide a flow of benefits such as reduced housing costs. In addition

assets, if liquid, can be used to smooth consumption over periods of limited

earnings, or illiquid assets can be used as a source of collateral for such

purposes. The SVDP noted that:

There can be no rational discussion of poverty without

consideration of wealth...Poverty exits against a backdrop of wealth. To

understand poverty in our community, we need also to address the environment of

wealth in which poverty is produced.[54]

3.54 Wealth is more

unevenly distributed than income and trends indicate that it is increasingly

concentrated in fewer hands in Australia.[55]

One study found that in 1967, 25 per cent of the wealth was concentrated in the

hands of just 5 per cent of the population – this had increased to 29 per cent by

1998. The wealth held by the top two quintiles grew between 1967 and 1998 while

the wealth of the bottom three declined. The study concluded that 'the trend

towards greater wealth equality from the start of the century to the 1960s did

not continue into the 1990s and may have reversed'.[56]

3.55

The estimated distribution of wealth in 2000 and projections to 2030 is

detailed in Table 3.7. The table shows that in 2000, the bottom 50 per

cent of the population held just 7 per cent of the wealth, whereas the top

one percent held 13 per cent of the wealth. The top 5 per cent of the

population held 32 per cent of the wealth. The table indicates that the

distribution of wealth will become more concentrated over the next 30 years.

The share of the bottom 50 percent is estimated to decline from 7 per cent

in 2000 to 5 per cent in 2030, while the share of the top 10 per cent

is projected to increase from 45 per cent to 50 percent over the same period.

Table 3.7: Estimated distribution of wealth by

selected percentiles, 2000-2030

|

Wealth Percentile

|

2000

|

2010

|

2020

|

2030

|

|

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

%

|

|

Top 1%

|

13.9

|

11.7

|

11.8

|

11.7

|

|

Top 5%

|

31.6

|

29.2

|

30.9

|

32.7

|

|

Top 10%

|

45.3

|

43.1

|

46.1

|

49.5

|

|

Top 20%

|

64.0

|

62.7

|

66.4

|

70.0

|

|

Bottom

50%

|

7.0

|

6.7

|

5.7

|

4.9

|

Note:

'Wealth' refers to the value of owner

occupied housing, equities, rental investment property, superannuation and

interest-bearing deposits.

Source: Kelly S, 'Simulating Future Trends in Wealth Inequality',

Paper presented at the 2002 Australian Conference of Economists, October 2002,

p.12.

Conclusion

3.56 Evidence

presented to the Committee and recent studies provide a profoundly disturbing

picture of the extent of poverty and deprivation in Australia. While the

numbers of those living in poverty varies between studies, even the most

conservative estimates point to substantial numbers of people in material deprivation,

struggling to make ends meet and largely excluded from social and economic

participation in the wider society. Those most at risk of poverty today cover a

wide range of groups living in various circumstances and spread throughout the

country – ranging from Indigenous Australians, the unemployed, sole parent

families, people on low wages and young people.

3.57 Evidence to the

inquiry and specialist reports have also highlighted a trend towards increasing

income and wealth inequalities in Australia. Statistics indicate that the

dispersion of earnings and income have become more unequal in Australia,

especially since the 1980s. While the impact of taxes, transfers (social

security payments) and other benefits, such as education, health and welfare

has resulted in some redistribution of income, inequality remains unacceptably

high in this country.

3.58 The wider

society must now face the consequences of increasing levels of poverty and

disadvantage in this country. In succeeding chapters the Committee has outlined

a series of strategies to address the persistence of poverty and deprivation in

this country that sadly co-exists amid affluence and general material

prosperity – a prosperity that has failed to be adequately shared by all

Australians.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page