Chapter 8

Planning ratio, allocations and funding of community care and high- and low-care

He who would pass his declining years with honor and comfort,

should, when young, consider that he may one day become old, and remember when

he is old, that he has once been young.

Joseph Addison 1672 – 1719

Introduction

8.1

This chapter considers whether the current planning ratio between community,

high- and low-care places is appropriate. It also addresses the impact of

current and future residential places allocation and funding on the number and

provision of community care places.

Current planning ratio

8.2

The current planning ratio of 113 places per 1000 people aged 70 years and

over is allocated as follows:

-

44 high care places per 1000

people aged 70 years and over;

-

44 low care places per 1000 people

aged 70 years and over;

-

25 (21 CACP and 4 EACH) community

care places per 1000 people aged 70 years and over.[1]

8.3

The process of allocating new places begins with an estimation of the

number of new places needed to meet increases in the target population. Aged

Care Planning Advisory Committees in each state and territory then consider how

new places should be distributed between regions and special needs groups and

advise the Secretary of the Department of Health and Ageing (the department) on

the most appropriate allocation and distribution by different types of subsidy

and proportions of care. Under the 2008–09 Aged Care Approvals Round (ACAR), 10

447 aged care places were allocated of which 73 per cent were residential places.[2]

8.4

The Aged Care Act 1997 specifies the objectives of the planning

process:

-

to provide and open and clear

planning process; and

-

to identify community needs,

particularly in respect of people with special needs; and

-

to allocate places in a way that best

meets the identified needs of the community.[3]

8.5

Persons with special needs are defined by the Aged Care Act 1997

as:

-

people from Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander communities;

-

people from non-English speaking

backgrounds;

-

people who live in rural and

remote areas;

-

people who are financially or

socially disadvantaged;

-

people of a kind (if any)

specified in the Allocation Principles.[4]

8.6

Of the planning system, the Department of Health and Ageing commented

that:

The planning framework ensures that the growth in the number

of aged care places matches growth in the aged population. It also ensure

balance in the provision of services between metropolitan, regional, rural and

remote areas.[5]

Issues with the current planning system

8.7

Providers raised a range of concerns in relation to the current planning

system. Amongst them, the Aged Care Association Australia (ACAA) stated that

the current system is:

...very inappropriate in meeting these objectives as the ratio

is not delivering a well planned and coordinated balance between demand and

supply.[6]

8.8

A major concern highlighted by a number of providers was that the

current planning system did not recognise the growth in residents in high care.

ACCA, for example, noted:

There appears to be little or no science to the increases in

the formula and only appear to be intended for one purpose namely, increasing

the number of community care places. The 2008 Report on the Operation of the

Aged Care Act 1997, shows that forty five percent of residents in low care

facilities are actually high care classified and that sixty nine percent of all

aged care residents are classified as high care.[7]

8.9

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) held that it was

timely to review the planning ratio, noting that whilst there has been a steady

rise in the number of permanent residents classified as high care including 70

per cent in 2007, only 49 per cent of places were designated as high care in

2007.[8]

At the same time, the AIHW cited the 2008 Report on Government Services which highlighted

that by 30 June 2007, 37 per cent of low care places were occupied by residents

with high care needs whilst 67 per cent of all operational places were taken up

by high care residents.[9]

8.10

Similarly, the Aged Care Association Australia – SA Inc held that the

current planning ratio is not appropriate as the residential aged care

population comprises 70 per cent high care residents. According to the

association, there exists a 'vast disconnect' between the actual residential

care population and the planning ratio between residential high and low care.[10]

Moreover, the association argued that as the proportion of high care residents

is bound to increase over time, the current ratio will become increasingly

inappropriate.

8.11

Mr Alan Gruner of The Brotherhood of St Laurance also commented:

The ratio, in terms of residential care, is fifty-fifty

between high care and low care. In our opinion, there should be a higher ratio

of high care—at least a 70 to 30 ratio—given the needs of people coming into

residential care and particularly the higher health care they need.[11]

8.12

Mr Gruner went on to state that the future with residential care 'is

very much towards the high end, not just because of the ACFI but because of the

needs of people as they age'. He noted that many clients requiring low care use

community care packages, where they can access those packages and 'that seems

more appropriate'.[12]

8.13

However, Mr Andrew Stuart, First Assistant Secretary of the Department

of Health and Ageing responded to such concerns:

Half of all residents entering care for the first time enter

at low care, but about 70 per cent of all residents in care at any point in

time are in high care. We think those two pieces of information are actually

quite separate considerations. The first one is about access and wanting to

make sure that people at both low-care and high-care levels can access aged

care appropriately. The second is about ageing in place. Once people are in

care they are able to stay in their current place and age in place within the

service.[13]

8.14

Problems with occupancy rates due to the planning system were also

raised in relation to the consideration of state-wide rather than local

demographic information. The House Group of Companies as one case in point

noted that their facilities have experienced vacancy rates of up to 94 per cent

due to 'flawed planning ratios which allowed more than six new services to

commence operation within a short distance from the Gleneagles, in

north-eastern Adelaide'. According to the group, in some areas there are

serious shortfalls in place, whilst in others, there has been an over-supply.[14]

8.15

Aged and Community Services Australia (ACSA) held the same view:

Currently little account is taken of services not directly

funded by the Australian Government, allocations are made on the basis of quite

large planning regions which sometimes mask the needs of specific communities

and it would be appropriate to test the effect of introducing a weighting for

the number of very old people (85+) in an area.[15]

8.16

Mr Greg Mansour of Aged and Community Care Victoria also commented that the

planning region model of planning leads to misallocations:

So what happens is the beds are allocated within a planning

region. The planning region boundary does not necessarily reflect the community

boundary, and you could have nearby towns where the boundary runs between those

towns...

Yes, I hear that feedback and I also hear it probably even

stronger in relation to community aged-care packages. It is not uncommon for

some of our members in certain geographic areas to have vacancies on one side

of the boundary and waiting lists on the other. So whilst the regional

boundaries are probably—and I can understand why they are important from a

planning point of view, but if they are inflexible and they do not operate

seamlessly, it will create a problem for communities and I get that feedback.[16]

8.17

Mr Mansour went on to argue that the planning system needs to allow

consumer choice so that the appropriate packages can be offered. However, Mr

Mansour contended that although this is critically important, there are a range

of barriers. For example, if a particular community had a high level of

interest in community care there is not a simple straightforward process to

allow for the swapping of low-care beds to community aged-care packages. Mr

Mansour concluded that 'there is a whole lot of systems that we have put in

place, I guess, as checks and balances that inhibit flexibility'.[17]

8.18

The relationship between planning ratios and occupancy rates and their

impact on the viability of aged care providers was highlighted by a number of

witnesses including the Royal College of Nursing, Australia which

stated:

Planning for distribution of approved residential and

community aged care places requires more strategic targeting with greater

attention given to maintaining a comprehensive service able to meet different

levels of resident needs. The low level of funding provided for occupied beds

means that aged care organisations rely heavily on high occupancy rates to be

sustainable.[18]

8.19

The ACAA estimated that the average occupancy in the industry has

significantly declined. Utilising June 2007 occupancy levels, the ACAA

maintained that the average occupancy has fallen to 93 per cent as at 30 June

2008.[19]

Indeed, the Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act 1997 for 2008

stated of the occupancy rate in residential care:

At 30 June 2008 there were 2,830 aged care homes delivering

residential care under these arrangements, with an occupancy rate of 93.86 per

cent over 2007-08. This compares to 94.5 per cent in 2006-07 and 95.2 per cent

in 2005-06.[20]

8.20

The ACAA argued that this declining occupancy rate has led to a context

in which there are 12 000 vacant places across the aged care system.[21]

8.21

Catholic Health Australia also noted that the planning and allocation

process fails to adequately reflect likely demand for places, particularly

residential care places and stated of the Aged Care Planning Advisory

Committees (ACPAC):

The ACPAC have only ABS Census data for the population 70

plus and between Census rounds the ABS and DoHA estimates by region and LGA.

The data doesn't always reflect actual population shifts, particularly in

geographic areas of high growth in older demographics. The methodology adopted

for determining ratios must be made transparent and should include assumptions

about socio economic status, access to services, ethnicity and expected

utilisation rates of services.[22]

8.22

Anglicare Australia also recognised that if planning ratios were set

with greater consideration of more localised social and demographic

information, clients in turn would have more information to make informed

decisions:

This would need to be accompanied by providing better

information to interested parties (existing and potential providers of both

residential and community care services; people who may be eligible for

assistance) on which to base their decisions on investments and care options.

It would also provide a platform to put more control and decision making power

in the hands of consumers rather than those of government and providers.[23]

8.23

Baptistcare amongst other providers highlighted the realities of family

relationships which impact on planning ratios. Of the current system,

Baptistcare stated:

It considers the numbers of aged people in a region and based

on those figures attempts to identify future need. It ignores changes that have

occurred in family relationships over recent decades and does not recognize

that people entering residential aged care are likely going to prefer residing

at a facility close to where their children live, rather than close to where

they previously lived.[24]

8.24

Mr Harold Milham of Alzheimer's Australia noted that the reform

proposals of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission to relate the

planning ratio with people rather than places was a means of breaking the

relationship between accommodation and care[25]

and providing greater choice for clients:

The approach to reform proposed by the National Health and

Hospitals Reform Commission has many elements that are in our submission to

your committee. We support the reform developed by the commission for

increasing choice in aged care by relating the planning ratio to people rather

than places, thus breaking the link between accommodation and care, and

providing choice for consumers for a mix of accommodation and care options;

basing the ratio on 85-plus, rather than 70-plus, to better reflect the

population group cared for; developing a national aged care program to provide

for the more effective integration of aged care services; and, finally, the

adoption of consumer directed models of care.[26]

8.25

The ACSA argued that the appropriate planning should take into account

three points:

-

The needs of older people for care

and housing extend beyond those provided under the Australian Government's aged

care program.

-

These needs need to be met in a

specific local area rather than 'in general', or 'statewide'.

-

The use of care services tends to

increase markedly with age.[27]

8.26

The Municipal Association of Victoria highlighted the need for consideration

of client characteristics and evidence of demand based on national datasets in

the establishing of planning ratios. Ms Kaye Owen explained:

In terms of a national aged-care planning framework, there

needs to be a coordinated development and use of supply, demand and utilisation

datasets. That fundamental need for data has been there for quite some time,

and it is an absolute necessity. There is opportunity to build on the local

area data and to incorporate a range of related program areas with agreed

processes with the three tiers of government and the involvement of providers

and consumers.[28]

8.27

Discussion on occupancy rates and differences between and within regions

exemplified what some providers viewed as an uneven distribution of places.

This reality has, according to Management Consultants and Technology Services

led to a situation in which there are 'serious shortfalls in places, and in

other areas of oversupply' in Victoria.[29]

The body concluded:

It would be of assistance to providers and assist them with

proper planning for places in appropriate allocations if they know where these

locations are. It would be helpful for all data at local LGA level to be

disclosed.

The current planning ratio should be an indicative model

only. For providers who wish to expand services to meet the true needs of their

community, there should be flexible model.[30]

8.28

The need for flexibility to meet local demand was also highlighted by

ECH Inc, Resthaven Inc and Eldercare Inc who stated that the current planning ratio

of 113 places per 1000 persons over 70 years of age should be retained but

that flexibility should also be introduced to the Aged Care Approvals Round to

enable variations in the residential and community care allocation ratio across

regions thereby enabling address of varying demand.[31]

8.29

On the other hand, Baptistcare argued for a market approach to planning

ratios:

The Governments targeted ratio of low-care, high-care and

community care places is excessively regulatory. There should be a market

approach, which will come to equilibrium between the three types of places

through the laws of supply and demand.[32]

8.30

Other concerns raised during the course of the inquiry centred on the

lack of information surrounding the establishment of current planning ratios.

According to the Western Australian Government, the calculation of the planning

ratios have never been explained:

The planning ratios are based on historically based planning

ratios that have evolved over time without a clear basis for their calculation

provided to the sector.

There has always been doubt associated with the calculation

of the planning ratios set in 1986 for low and high residential care for the

target population.

A transparent explanation has never been provided by the

Australian Government leading to concerns that the planning ratios have led to

an inherent systemic shortfall in allocated places in general over time.[33]

8.31

The planning ratios have not been comprehensively reviewed since they

were first introduced in 1985. The department itself noted that whilst changes

had been made to the ratios since their establishment, there have been

'significant demographic changes and changing patterns of use in aged care

services'.[34]

In terms of the changes, in 2004, in response to the Hogan Review, the Commonwealth

increased the operational provision ratio from 100 to 108 places for every 1000

people aged at least seventy, to be achieved in 2007. Further review in 2007

resulted in this ratio increasing to 113 places (88 residential and 25

community care) for every 1000 people aged 70 years or older by December 2011.

The balance of places within the provision ratio was also adjusted to increase

the number of community care places from 20 to 25 places for every 1000 people

aged at least seventy; four of these are for high level community care in the

form of EACH or EACH-D packages. Adjustments were also made within the

residential care target ratio of 88 places per 1000 people aged 70 years

or over to increase the provision of high care from 40 to 44 places.[35]

8.32

According to the 2008 Report on the Operation of the Aged Care Act

1997, the department is currently planning to initiate a review of the aged

care provision ratio.[36]

8.33

At the same time, however, Mr Andrew Stuart, First Assistant Secretary

of the department highlighted that:

There are very considerable strengths in the current planning

arrangements. We tend to take those for granted in Australia, but I think they

are very important to mention. First of all, the planning formula keeps growth

in care in line with growth in the ageing population and, secondly, the

planning formula directs new aged-care places to the areas of greatest need.

Aged care is really one of the very few areas in public policy where growth in

expenditure actually goes up in line with growth in the population. It is also

one of the few areas of public policy where growth in rural provision actually

matches the proportion of the population that lives in those areas. If you are

thinking about policy in the area of planning and allocation, you would not

want to lose those strengths that we currently have.[37]

8.34

The department also commented on arguments that a planning arrangement

based on 80 years of age rather than 70 years of age should be introduced to

more closely reflect the average age of residents. In response to such

suggestions, the department noted that:

-

a very good forward predictor of future demand is the population

aged over seventy. Despite impressions to the contrary, older people are not

highly mobile and they want to access care where they have been living; and

-

to move from a ratio based on seventy years of age to one based

on eighty years would soon (from 2013) produce a reduction in the release of

new places, and a concomitant saving in government expenditure, because growth

in this population will be less rapid than the total growth in those aged over

seventy. From the year 2021 there would then be a rapid surge in the number of

places required. This surge may challenge the industry's capacity to meet it

since it would produce a release of aged care places which is higher than any

release to date. The ratio based on those aged over seventy produces a steadier

growth path.[38]

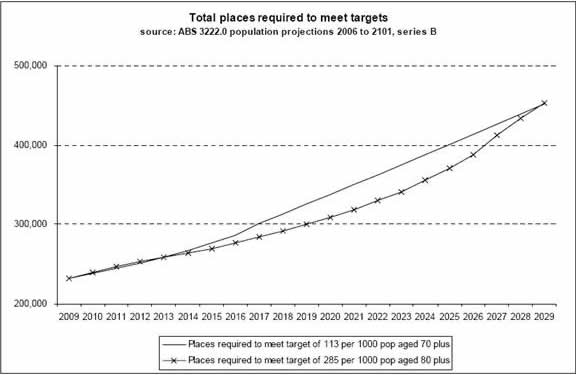

8.35

The department provided the following graph to illustrate the latter

point.

Figure 8.1: Total places required to meet targets

8.36

The department also responded to comments concerning whether there is an

ongoing need for a distinction between low care and high care as there is

increasing utilisation of low care places by high care residents. The

department pointed to the distinction between accessing aged care services and

ageing in place.

8.37

In relation to access, the current aged care planning ratio for low and

high care are used for planning purposes and seek to ensure that places are

available for residents who need either high or low care on admission.

Currently, admissions are distributed evenly between high and low care (49.97

per cent entered as low care in 2007–08). According to the department, to

remove the ratio distinction between low and high care could result in reduced

access for low care residents.[39]

8.38

In relation to ageing in place, this policy is designed to enable clients

to remain in the same environment as their care needs increase where facilities

are able to offer the accommodation and care they require. Once a client has

entered care they are now generally able to remain in the same residential care

service as his or her care needs increase. As a result of ageing in place, the

number of care recipients who are actually receiving high level residential care

is significantly higher than 50 per cent. Indeed, as at 30 June 2008, some 69

per cent of residents in aged care homes were receiving high level care.[40]

8.39

The department went on to state that ageing in place is supported by the

current funding system with the ACFI a better and more objective measure of a

residents' care needs. With the introduction of the ACFI, the government has

allowed care needs to be reassessed at any time, so that significant increases

in frailty can be funded immediately. This further supports the policy

objective of ageing in place.

8.40

The department concluded:

In summary, policy over the last decade has consistently

emphasised relative growth in care at home, access to both

residential low care and high care, and the capacity for enduring care once a

resident is in the residential care setting.[41]

Conclusion

8.41

The committee recognises the new and emerging challenges facing the

industry in meeting growing demand and increasingly diverse client needs and

expectations. For this reason, the committee believes that it is timely for a transparent

and comprehensive review of the planning ratios. Such a review would provide an

opportunity to consider demographic and social information not currently

utilised and to deliberate on the impact of growing demands on the sector.

8.42

Such a review should consider the continuum of care as a long term

solution for the aged care sector and look beyond the distinctions between high

and low care. For this reason, the committee recommends that the suggested

taskforce review long-term options for the provision of aged care in Australia

including continuity of care.

Recommendation 30

8.43

The committee recommends that the suggested taskforce undertake a review

of the current planning ratio for community, high- and low-care places. Drawing

on all available demographic and social information, the review is an

opportunity to assess the planning ratio in light of growing and diverse demand

on aged care services.

Recommendation 31

8.44

The committee recommends that the suggested taskforce review continuity

of care as a potential long term solution for the aged care sector.

8.45

It should also be noted that witnesses drew a parallel between an effective

planning ratio and capital funding. According to the ACAA, the level of

investment in capital works ($1.45 billion in 2007–08) is not sustainable if

the Government continues to allocate places at the current rate and does not

assist with the cost of maintaining vacant places.[42]

Similarly, Aged and Community Services Association of NSW and ACT held that

planning ratios will not be effective until capital funding concerns are

addressed:

With expected increase in demand for higher levels of care in

the community the allocation of Extended Aged Care at Home (EACH) or EACH

Dementia (EACHD) would need to be increased. However changes in planning ratios

will not be effective if the underlying recurrent and capital funding

inadequacies are not addressed at the same time.[43]

8.46

Chapter 4 of this report considers the issue of capital funding in

greater depth.

Impact of current and future residential place allocations and funding on

community care places

8.47

With the growth in the number of older people living in their home for

longer periods of time, demand has risen for services in the community. The

Commonwealth provides these services through Home and Community Care (HACC)

programs, Community Aged Care Packages (CACP) and Extended Aged Care at Home

(EACH) Packages.

8.48

The department noted that in response to the increasing demand for

community care programs as an alternative to low or high level residential

care, the Commonwealth has been rapidly increasing the number of available

community care package places. CACP places increased 43.6 per cent over five

years from 2003–04, while EACH high care packages have increased nearly

five-fold since they were introduced in 2003–04.[44]

8.49

In evidence, some providers argued that the growth in community aged

care packages was leading to excess vacancies in residential aged care. Aged

and Community Services Association of NSW and ACT stated:

The consumer choice is towards community care, rather than

residential care and the current planning ratios may result in too many beds

for an aged population resulting in reduced occupancy rates and subsequent

viability issues.[45]

8.50

Emphasising growing client expectations to remain at home for as long as

feasible, Anglicare Australia argued for a change in the ratio between high and

low care:

Most people want, and have the means, to remain in their own

homes as long as possible, with an accompanying high demand for community based

care. This obviously reduces the demand for low level residential care. This

trend is likely to continue. This demands a recalibration of the planning ratio

to better reflect older people’s preferences and usage. The split between new

high and low level care residential places should be immediately shifted to

70:30, with future ratios being determined by actual and projected take up of

places.

This strongly suggests that the balance between residential

and community care needs re-examination, as does the provision of low and high

level care in the community (CACP and EACH) and the ease with which people are

able to transition from lower to higher levels of care in the community. The

current number of places available (for example, the Victorian ratio is 19.4

CACP places per 1000 population aged 70 years and over and 2.4 EACH places),

funding levels, as well as eligibility criteria for, CACP and EACH preclude an

easy transition, leaving many people no option but to enter residential care

before they are ready. There is a need for a continuum of care model to be

introduced, with greater flexibility to meet increasing levels of care need

and/or different care needs, and with planning ratios more accurately

reflecting likely demand for higher levels of care.

It is time to re-examine the level at which the number of

overall places is capped and whether ratios between residential and community

care need to be retained or could be abandoned, giving more flexibility in the

market.[46]

8.51

However, the Royal College of Nursing, Australia cautioned

the unintended consequences of emphasising community care:

Where feasible and safe, planning is

placing greater emphasis on providing community care services due to a

preference of many older people to remain at home for as long as possible.

However, the unintended consequences have seen a reduction in access to

residential care and a greater burden on families and carers who provide aged

care with little training; no supervision; meagre resources and at times having

to forgo paid employment to do so. Moreover, as people are remaining at home

longer, their overall condition can deteriorate to such an extent that when

they access aged care they require high care having not received the benefits

of good nutrition, informed care and essential treatment and skilled nursing

staff.[47]

8.52

The department responded to concerns about excess vacancies in

residential care resulting from a growth in community care. It noted that it

had not been able to produce analysis which supports or denies this view,

despite attempts.[48]

The department went on to state:

Intuitively, at some level, providing older people

with greater choice in care modality (in their own home or in an aged care

home) will lead to some reduction in interest in residential aged care.

However,

-

choice

in care setting is an explicit goal of policy; and

-

there

is evidence to show that people with high level needs who

are living alone and have no carer are more at risk of admission to

residential care (Australian Institute for Primary Care). Consequently there is

only a partial overlap between those who choose care at home and those who need

residential aged care.

The Department considers that the overriding dynamic in

explaining vacancy levels in aged care currently is not one of competition

between care types, but of rapid growth in care places leading to temporary

vacancies.[49]

8.53

The department went on to give an example of an area where a new

facility may be opened even though there are vacancies in existing facilities.

The department stated that the vacancy level 'will be a temporary effect

relating to growth' and concluded:

In situations like these, not all providers welcome the

expansion of aged care places but this expansion is essential to meet the

overriding public policy objective of meeting the growing demand of the ageing

population, which is expected to double in the next twenty years...

It is the Government’s intention to facilitate choice and to

continue to emphasise growth in care at home. Sufficient vacancies in both

community and residential care ensure people can get a place in the care of

their choice without undue delay; with providers competing amongst each other

to attract customers on the basis of quality of care and amenity.[50]

Conclusion

8.54

In light of the fact that the committee has recommended an overarching

review of the aged care sector and indeed supports a comprehensive review of

the planning ratios, it considers analysis of place allocations and funding as

integral to both such reviews.

Senator Helen Polley

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page