Chapter 5

Should the package be scaled back?

5.1

Even if there was a case for timely large fiscal stimulus packages to

meet an imminent recession, it can be argued that the economic environment has

improved significantly and so a smaller stimulus would now be appropriate.

5.2

Those witnesses who opposed the stimulus package argued that the

stimulus was far too large and were of the opinion that the scaling back of the

stimulus package should happen sooner rather than later to ensure that the cost

to the economy did not exceed the benefits.

...I thought it was unnecessarily large at the outset. So:

winding it back, scaling it right back, and trying to prevent any further commitments

that do not meet a basic cost-benefit test, essentially. All projects from now

on should be rigorously examined as to their benefits because the ultimate test

is whether the benefits exceed the costs in terms of the interest paid abroad

to foreigners.[1]

5.3

Given the recent economic data that has been published by a number of

outlets including the Treasury and the Reserve Bank of Australia, it is the

opinion of the Committee that the three 'T's that have been espoused by

Treasurer Swan needs to be expanded to include a fourth "T",

tweakable. This would reflect the ability of the Treasurer to work with the new

economic data and make effective decisions about future spending in the

Australian economy.

We set clear criteria that stimulus be timely, temporary and

targeted. And we met them.[2]

But perhaps the lesson from the crisis that his stimulus

needed a fourth T – tweakable.[3]

The change in the economic outlook since October 2008

5.4

The first stimulus package was introduced in October 2008 when

the collapse of Lehman Brothers had shaken global financial markets. The IMF's

October 2008 World Economic Outlook stated:

The world economy is entering a major downturn in the face of

the most dangerous financial shock in mature financial markets since the 1930s...The

situation is exceptionally uncertain and subject to considerable downside

risks. The immediate policy challenge is to stabilize financial conditions,

while nursing economies through a period of slow activity and keeping inflation

under control.[4]

5.5

The Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2008-09 released in November

2008 commented that the global financial crisis had 'entered a new and

dangerous phase.' While Australia was better placed than most to withstand the

fallout, it 'was not immune from the effects of the global financial crisis and

the global downturn'.[5]

5.6

In February 2009, the Updated Economic and Fiscal Outlook noted

that the global outlook for the global economy had deteriorated sharply, with

the IMF cutting its forecast (Chart 5.1) for global growth and now forecasting

a deep global recession.[6]

Chart 5.1: World GDP

growth

5.7

It warned that 'the weight of the global recession is now bearing down

on the Australian economy. Growth is expected to be significantly weaker than

previously anticipated and unemployment will be higher.'[7]

5.8

The recent economic evidence suggests that the Updated Economic and

Fiscal Outlook greatly over predicted the impact on Australia, regardless

of the impact or otherwise of domestic stimulatory policies.

He agrees the stimulus has limited the downturn. "But

there are hard times ahead," he writes. "Sustainable full employment

will require reduction of average incomes and living standards below those to

which Australians became accustomed before the crash. The Australian

government, community and business leadership has barely begun to contemplate

the adjustment that is required."[8]

5.9

The economic outlook now looks more favourable. The IMF's World

Economic Outlook Update of July, 2009 states:

The global economy is beginning to pull out of a recession

unprecedented in the post–World War II era, but stabilization is uneven and the

recovery is expected to be sluggish. Economic growth during 2009–10 is now

projected to be about ½ percentage points higher than projected in the April

2009 World Economic Outlook (WEO), reaching 2.5 percent in 2010.[9]

5.10

The Australian economy has rebounded far better than Treasury estimated,

and the Governor of the Reserve Bank provided three reasons as to why Australia

has been the best performing economy in the OECD:

Firstly, our financial system was in better shape to begin

with, being relatively free of the serious problems that the British, the

Americans and the Europeans experienced.

Secondly, some key trading partners for Australia have proven

to be relatively resilient in this episode... China will easily achieve their

eight percent growth target for 2009, led by domestic demand. Many of our other

Asian trading partners also have returned to growth recently. Ongoing strength

and demand for resources has kept Australia's exports growing and ours terms of

trade, even though well off their peak, remain quite high by historical

standards.

Finally, Australia had ample scope for macroeconomic policy

action to support demand as global economic conditions rapidly deteriorated,

and that scope was used. The Commonwealth budget was in surplus and there was

no debt, which meant that expansionary fiscal measures could be afforded. In

addition, monetary policy could be eased significantly without taking interest

rates to zero or engaging in the highly unconventional policies that have been

needed in a number of other countries.[10]

5.11

The fact of the matter is that the Australian economy has rebounded from

the global financial crisis as a result of the strong prudential regulations

and other legislative instruments that kept the Australian financial sector out

of most of the trouble associated with the problems in other countries.

Our banking system has continued to earn a positive return on

its capital, unlike those in a number of other countries.[11]

5.12

Both official and private sector economic forecasters have become more

optimistic. As an example, the evolution of the Reserve Bank's forecasts is

shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1: RBA

forecasts of through-the-year growth in real GDP, by

date of forecast

| |

Nov 2008 |

Feb 2009 |

May 2009 |

August 2009 |

|

2009 |

1½ |

½ |

-1 |

½ |

|

2010 |

2 |

2½ |

2 |

2¼ |

|

2011 |

n.a |

n.a |

3¾ |

3¾ |

Source: RBA, Statement on

Monetary Policy, various issues.

5.13

Treasury spoke of their improved confidence:

...it is no secret that the next set of economic forecasts will

likely include stronger forecasts of gross domestic product growth and a peak

unemployment rate lower than the 8½ per cent that was forecast at the time of

the budget. Much economic data released since the budget has been more

favourable than we or indeed others expected. Business and consumer confidence

in particular have proved to be remarkably resilient. Australia’s export

performance has also been surprisingly strong...[12]

5.14

This is reflected by the Reserve Bank's decision to increase the cash

rate to 3.25 per cent and it could result in an increase in unemployment or a

reduction in the number of hours worked.

Our job is to not only try to manage that path in a way that

pays due regard to the unemployed and all that goes with that, of course, but

also to try to make sure that we do not give ourselves some bigger problems

down the road – which, if we had those, would be very detrimental to the

unemployed.[13]

5.15

However, Treasury were cautious about the outlook, despite the Reserve

Bank of Australia considering the balance of risks now rendering the current

very expansionary setting of policy no longer necessary or possibly imprudent:

The world recovery is only in its early stages. Those elements

of domestic demand that have performed the strongest have been assisted by

fiscal and monetary stimulus and, in particular, household consumption and

parts of business investment have been greatly assisted. Evidence of a self‑sustaining

recovery in private activity remains tentative at this time. ...all credible

forecasters are expecting the economy to continue to operate below its

productive capacity in the next year or two, even taking into account the

stimulus still to come.[14]

5.16

It was pointed out by Treasury, the Reserve Bank and ACCI that the

package always envisaged a gradual withdrawal of the stimulus (see Chart 2.1

and Table 2.1 above):

We are beyond the period of peak impact of the fiscal

stimulus. From that point, as stimulus is to be gradually withdrawn, the

contribution to economic growth will subside and it will soon turn negative.

Indeed, on our estimates, the fiscal stimulus package will make a negative

contribution to GDP growth in every quarter in 2010...[15]

In due course both fiscal and monetary support will need to

be unwound as private demand increases. In the case of the fiscal measures,

this was built into their design. The peak effect of those measures on the rate

of growth of demand has probably already passed. The extent of support will tend

to tail off further over the next year or so.[16]

...within the fiscal stimulus arrangements proposed by the

government there is an inbuilt winding down in any case. For example, the

household spending initiatives are gone; the first home owners boost is being

wound down from the end of this month; and the investment allowance proposals

for large business ended on 30 June and for small business will end at 30 December.[17]

5.17

The debate is therefore more properly about whether the withdrawal

should be accelerated.

As things change, you need to recalibrate your policy.[18]

By the government's own account, growth (in 2011) would be at

4.5 per cent, so why are we still stimulating the economy.[19]

5.18

Making judgements about the direction of the stimulus package requires balancing

risks, and when asked about the need for an alternative plan to use the

remaining stimulus in the face of an overheating economy, the Governor of the

Reserve Bank was open to the recalibration of the packages.[20]

5.19

The Committee considers that we need to take into account a serious risk

that maintenance of excessive stimulus for too long could raise unemployment

through its effects on interest rates and the crowding out of more productive

private investment. More recently, it has been suggested that the fiscal

stimulus should be unwound more quickly than scheduled.

If growth is stronger than Treasury had anticipated at the

time it was put in place then it would be appropriate to bring it back faster.[21]

5.20

The view that accelerated withdrawal of the stimulus package now would

be premature is not shared by the Committee. The Committee strongly believe

that the recalibration is warranted and fortified by the recent increase in the

official cash rate, and are of the opinion that the fourth "T" must

now come into play.

As the economy picks up, the fiscal stimulus could push up

interest rates... Swan this week suggested that Australia's fiscal stimulus was

"best practise". First, it was much more "timely" than the

delayed Keating government stimulus response to the early 1990s recession...

Second, Swan suggested that his stimulus was well "targeted" because

the first stage of cash handouts to lower income earners and families provided

a quick-acting boost to consumer spending... Third, Swan told an Australian

Business Economists lunch that the clear timetable for withdrawing the stimulus

meant it was suitably "temporary". But perhaps the lesson from the

crisis is that his stimulus needed a fourth T – tweakable.[22]

5.21

The Reserve Bank of Australia agrees that the fiscal stimulus should be

wound back but does not state that it should be done as urgently:

I think it is a bit hard to claim that as of this moment

there is too much growth in the economy. I have not had a serious problem with

what has occurred on the fiscal front thus far. The presumption we are making

is that things will be delivered and then wound back more or less on the

schedule that is set out in the budget...I am not sure that I would say that that

outlook is a terribly worrying outlook really. This has been a good episode for

Australia. We have come through this well. We are in recovery now, I think. It

is important that these measures be wound back over time, but they are on track

to be so.[23]

5.22

Additionally, there is concern that the maintenance of the package for

an extended period of time will result in an increase in government investment

and the crowding out of more productive private investment.

Public debt has the effect of crowding out private investment

and increasing interest rates.[24]

5.23

Respected economic commentator Professor Ross Garnaut has warned the

Government of the dangers associated with maintaining the inefficient and

wasteful fiscal spending:

By further fuelling excess spending, the Rudd Government's

budget stimulus will have to be followed by "hard times" and lower

living standards that the government has "barely begun to

contemplate".[25]

He argues Australia's macro-economic policy response to the

global financial crisis has relied heavily on one of the biggest and earliest

budget expansions of any high-income country and less on lower interest rates.[26]

5.24

The Governor of the Reserve Bank was asked as to the impact on interest

rates if the remaining stimulus spending was not spent and clearly stated that

it would impact on interest rate pressures:

If the presumption is an impact on demand that is $20 billion

of $30 billion less, over three years that is a level of demand that is nearly

a percent of GDP a year lower. So, all other things being equal, the course of

the economy would be a bit different. What we are responding to is total

demand, more or less, rather than where it comes from. It is really the total

that counts more. So in that hypothetical scenario, yes, I think that would

have some bearing on the future path of interest rates.[27]

The fiscal package as a commitment

5.25

The Committee also heard the argument that the package should be

implemented as promised even if it now may be viewed as slightly larger than

required, but does not accept this in itself as a valid reason to continue

fiscal policy of a size and spend that is capable of distorting the economy:

...when you are announcing the program you have got to

understand that circumstances may well change and you should stick with that

program. Because of the change in direction that you give, the signals that you

give economic actors to their businesses and the people who will be employed in

them, quite deliberately, you ought to stick with them.[28]

5.26

It can be argued that this is a rather empty argument and a result of

the poor design of the stimulus package to start with. The cost to the economy

for maintaining the stimulus package at the current rate could result in

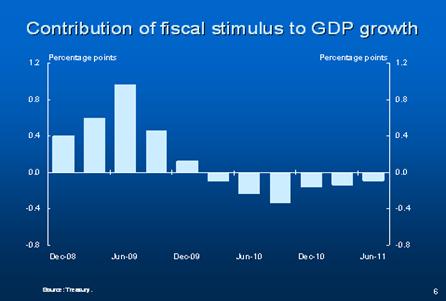

negative pressure on GDP growth (see chart 5.2).

The stimulus will be detracting from GDP growth from the

start of 2010...[29]

Chart

5.2: Contribution of fiscal stimulus to GDP growth

Source: Treasury[30]

5.27

Given the design of the stimulus packages, there has been some media

comment as to how the packages could be tweaked to maximise their benefit to

the Australian economy.

It could have begun with a burst of cash handouts and an

initial capital works budget for the first nine months of so. Then the Treasury

could have produced an updated economic assessment to guide the final size and

withdrawal of the remaining stimulus. That might conclude some of the

investment spending should be delayed, better planned or shelved.[31]

5.28

As an alternative means of reducing the stimulus package expenditure,

given that much of the stimulus package has already been spent and the

remaining expenditure could be delayed or spent over a longer period of time

which would have the effect of reducing annual expenditure but retaining the

total spending over a longer timeframe.

In summary, it notes that around $79 billion of what may

broadly be characterised as fiscal stimulus measures are expected to impact on

the economy over three years from 2008-09 through to 2010-11.[32]

Inflation and unemployment – the balance of risks

5.29

Many witnesses are concerned about inflationary risks from the package:

...given the qualitative easing which may have occurred and

given the fact that the Reserve Bank may have compromised the quality of its

balance sheet, that there may well be inflation down the track. I think the

ball is very much in the Reserve Bank’s court. If it will accommodate the

amount of spending which the government has undertaken and is continuing to

undertake then inflation can arise out of all of this.[33]

5.30

Others are focused more on unemployment risks:

We know that the best predictor of poverty in Australia is

not having a job, so trying to minimise job loss is important in the short term

and, as I think we spoke about earlier, the long term. If kids experience a

period of unemployment early in their careers, you can see that in their wage

trajectory and their occupation later on in their careers. They recover, but

not fully. I think that is partly due to the loss of skills, the absence of

gaining experience and just the psychological impact of the feeling that you

are not worth employing. So, to the extent that policy can ameliorate unemployment,

I think that should be a top policy goal.[34]

There has been no evidence presented to this committee that I

am aware of, and certainly none presented by the Governor, that suggests that

we have any imminent inflationary pressures.[35]

5.31

Despite this, the October 2009 minutes of the Reserve Bank of Australia

meeting clearly indicate the RBA holds concerns about underlying inflation and

now predict that the expected trough in inflation will be significantly higher

than earlier thought.[36]

5.32

Over the course of the inquiry, the Government has been changing its

rhetoric and appears to be preparing to recalibrate the remaining components of

the fiscal stimulus packages.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page