Chapter 2

Key comments

2.1

All submissions received by the committee supported the Bill, except for

some concerns relating to the Family Assets Test (FAT) and personal income test,

with organisations commenting primarily on the Youth Allowance (YA)

parental means test provisions in Part 1 of Schedule 1. The Isolated Children's

Parents' Association of Australia (ICPAA), for example, submitted:

Our organisation supports the introduction of this bill...to

remove the Family Assets Test, the Family Actual Means Test and the altering of

the Parental Income Test for students who wish to access dependent Youth

Allowance...Removal of these tests will present more opportunities and improve

access to tertiary education for the rural and remote cohort, who already have

disproportionately lower participation rates when compared to metropolitan

students. These changes will provide a predictable, straight forward pathway

for families to access financial assistance that reflects fluctuations in

income while they continue supporting their children, transitioning from school

to further study.[1]

2.2

The three separate tests that comprise the parental means test—the FAT,

the Family Actual Means Test (FAMT) and the Parental Income Test (PIT)—were

the focus of submitters' brief comments. Submitters also described the

circumstances of families in rural, regional and remote Australia with respect

to supporting their young people in education and training.

Circumstances of families in rural, regional and remote Australia

2.3

Several submitters described the circumstances of families in rural,

regional and remote Australia, whose young people often have to live away from

home to access education and training opportunities.

2.4

The South Australian Isolated Children's Parents' Association referred

to the financial burden of accessing these opportunities and how this burden

prevents, or discourages, young people from pursing higher education and

training:

Sending children away from home to university or TAFE

encompasses many relocation and ongoing costs including housing, utilities,

furniture, fees, textbooks, clothing, food and travel. Children from rural and

remote areas that are currently ineligible for Youth Allowance feel the

pressure that is exerted on their parents to pay for their education. Many are

unable or unwilling to take up opportunities for further study due to this

financial burden.[2]

2.5

The Northern Territory Isolated Children's Parents' Association stated that

while families may have farming assets, they also have limited financial means:

...the family assets test...is penalising outback families, who

have to purchase large assets to work their land and make a life of it, often

very sacrificially. This usually means that although some families seem to be

rich in assets, these assets are not luxury items but generally machinery and

the like that is necessary to carve out a life from the dust in this outback

land, usually these very families have very, very little general funds or

available cash flow to live on week to week, and to say they go without is

putting it mildly.[3]

2.6

The ICPAA submitted that equitable access to tertiary education is being

stifled by considerations of socio‑economic status and geographic

location:

Currently the aspirations of rural and remote young people

are being driven and dictated by their ability to access financial support to

assist with relocation and living costs while they study.[4]

Box 1: Case Study

I have been asked to share

my experiences to highlight the challenges and barriers for remote students in tertiary

study. My husband and I live outside Longreach on a cattle property. We have 2

boys, one in year 12 at boarding school (Brisbane) and the eldest is in his

first year at QUT doing Law and Bio Medicine boarding at Kings College, UQ.

Both our boys are interested in furthering their education in Brisbane at Uni,

so of course have to leave family and home to do this, 1300 kms away. Both

boys are 17 when graduating from secondary.

I must say my husband and I

have been surprised at how difficult it is to find financial support once

leaving the Secondary system. We had very little option but to choose

independent youth allowance, like most of us in agriculture we don’t meet the

dependant criteria because of assets, even though we are in the middle of a raging

drought!

I believe these young people

should be encouraged, nurtured and supported into a positive learning

environment so that we can have educated rural talent returning to agriculture.

We are losing them at an alarming rate, without support from government for

remote families and youth to enable them to continue study; we will not be

sustainable for the future.

Source: ICPAA, Submission 5, p. 5.

Dependent v Independent Youth

Allowance

2.7

A particular concern identified by some families and the Youth Affairs

Council of Western Australia (YACWA) was the distinction between dependent YA

and independent YA. These submitters stated that rural, regional and remote

students, in the attempt to qualify for independent YA, which is not subject to

parental means testing, defer and do not return to further education.[5]

2.8

ICPAA indicated that the Bill will ameliorate this situation, by

facilitating access to youth payments:

[The Bill] should enable a larger number of geographically

isolated students the option to take up tertiary studies the year after

finishing school and reduce the risk of not returning to study after deferring,

by giving them some financial support. Once a rural and remote student

qualifies for dependent Youth Allowance, they are then able to access the

Relocation Scholarship and Student Start‐up

Scholarship thus further assisting this group of students to access university

courses.[6]

2.9

On the other hand, YACWA suggested a broader solution—that the

Department of Social Services (Department) should review, with a view to

reducing, the 18-month work period required to prove independence.[7]

YACWA argued that this period is one of 'the largest systemic barriers to

higher education and training for young people living in rural Australia'.[8]

2.10

The committee acknowledges YACWA's concerns, which are not the subject

of this Bill, and notes that this is a matter on which the Interdepartmental

Committee on Access to Higher Education for Regional and Remote Students might report

shortly.

Youth Allowance parental means test arrangements

2.11

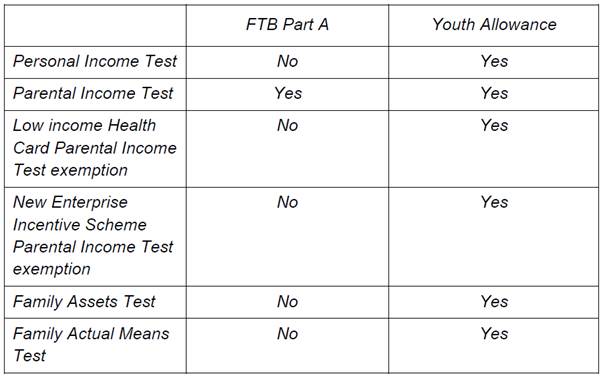

Part 1 of Schedule 1 of the Bill aims to align the YA parental means

test arrangements with the existing arrangements for Family Tax Benefit Part A

(FTB–A).[9]

A comparison of the means test arrangements is depicted in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Comparison of means test arrangements: Family

Tax Benefit Part A and dependent Youth Allowance

Source:

Department, Submission 6, p. 3.

Key provisions and their

anticipated affect

2.12

Item 2 of Part 1 replaces subsection 547B(2), to exclude non‑independent

people from application of the youth allowance assets test (the FAT and the

personal income test), from 1 January 2016. This amendment is

expected to enable around 4,100 additional claimants to qualify for dependent YA

(a two to two-and-a-half per cent increase), with an average annual payment of

more than $7,000 a year:

It would particularly benefit students and their families

from regional and remote areas, who often have large assets which are assessed

under the FAT, while at the same time being more likely to have lower adjusted

taxable incomes than their metropolitan counterparts that would then attract

YA.[10]

2.13

Items 8–10 and item 15 of Part 1 amend Module G–Family Actual Means Test

of the YA Rates Calculator, as set out in section 1067G of the Social

Security Act 1991, to remove the FAMT and references to that test in the YA

Rates Calculator. This amendment will enable around 1,200 more people to

access YA for the first time, and increase payments for around 4,900 current YA

recipients by approximately $2,000 a year.[11]

2.14

Items 12 and 16 of Part 1 amend the YA Rates Calculator:

-

repealing table item 11 in Module L–Table of pensions, benefits,

allowances and compensation, to remove the exemption from the PIT for people

with a parent who receives a Commonwealth allowance under the New Enterprise

Incentive Scheme (NEIS) (item 16); and

-

repealing paragraph 1067G-F3(e), to remove the exemption from the

PIT for people with a parent who qualifies for a low income health care card

(item 12),

from 1 January

2016.

2.15

The Department advised that, under the Bill, 'assistance would be

reduced for approximately 270 recipients, with an average fortnightly reduction

around $85'.[12]

Comments from submitters

2.16

The ICPAA supported the amended parental means test arrangements,

submitting that the new arrangements will allow for consideration of actual

family and business circumstances:

In addition [to highly illiquid assets], many rural families

are having to bear the cost of several years of boarding school for their

children's secondary education as well as paying boarding school fees for

siblings simultaneously while older children study at university level. [The

Part 1 of Schedule 1 measures are] a more realistic system that will allow

rural and remote families access to financial help to send their children away

for tertiary studies[.][13]

2.17

The YACWA supported the removal of the FAT and FAMT, stating that the

measure will promote rural students' equal participation in tertiary education

through enhanced access to income support:

...YACWA supports the Government's decision to remove the 'Family

Actual Means Test' and the 'Family Assets Test' from the current

statutory means testing regime, to the extent that doing so will increase

access to youth payments for young people whose family's asset wealth may have

provided an impediment to accessing government assistance.[14]

2.18

In addition to access, the YACWA identified several benefits that might

result from the elimination of the FAMT:

Under the current system, in order to satisfy the Family

Actual Means Test a young person is required to provide the Department with

details about both the spending and savings of every member of their family

during the relevant fiscal year. The onerous nature of the test can lead to

long delays in receiving payments as well as acting as a disincentive for young

people to apply for youth payments.

The sheer complexity involved in listing and valuing assets,

as well [as] documenting expenditure and savings for all family members can

also lead to inconsistent and inaccurate payments. This process itself can in

turn service to discourage some young people from pursuing tertiary education

or training.[15]

2.19

On this point, the Department noted that the regulatory burden will be

reduced for around 30,000 families who are currently subject to the FAMT: 'there

is a large regulatory burden yet there is only an impact in about 6,000 (20 per

cent) of cases'.[16]

2.20

The National Welfare Rights Network (NWRN) and the Australian Council of

Social Service (ACOSS) did not support the proposed removal of the FAT and the

personal income test from the YA parental means test arrangements.

2.21

ACOSS submitted that there is no clear justification for this measure:

A basic principle of our income support system is that people

who have the financial means to provide for themselves do so. Any inconsistency

in the treatment of assets between youth and family payments could be dealt

with by extending assets testing to family payments.

We understand the assets test currently affects rates of payment

for only a small minority of families receiving Youth Allowance but it is

likely to become more important in future years as household wealth increases.

If there are anomalies in the assets test treatment of farms, these should

be resolved across the social security system rather than by exempting one

payment.[17]

2.22

NWRN similarly argued that removal of asset testing for YA undermines

the fairness and consistency of the means testing of social security payments:

The means testing arrangements for social security payments

include both income and assets to ensure that payments are targeted to those

most in need. The inclusion of assets in the means test is intended to ensure

that assistance is targeted to those who lack the means to support themselves.

Removal of the personal and family assets tests for dependent

youth allowance runs contrary to this basic principle of the social security

system. It has the potential to enable government support to be paid to

families or individuals with relatively high levels of assets.[18]

2.23

The NWRN contended:

If there are inequities in the application of the family

assets test to certain families, these should be identified and dealt with by

modifications to, or exemptions from, the current assets test–not by

abandoning a bedrock aspect of the social security system.[19]

2.24

NRWN and YACWA supported aligning the PIT exemptions with the FTB–A

arrangements.[20]

The YACWA submitting that this measure should serve to increase access to youth

payments for young people in regional Australia and potentially several

thousand additional young people across the country:

It is to be commended that the changes to the 'Parental

Income Test' will, in certain circumstances result in a reduction to

high effective marginal tax rates, however YACWA is concerned that Youth

Allowance parental means testing will consequently cease to consider the

potential for income minimisation, with respect to family assets, in order to

take advantage of high payments.[21]

Income tax minimisation

2.25

ACOSS and the NWRN both raised the issue of income tax minimisation,

arguing that existing provisions in the PIT are not sufficient to ensure the

integrity of YA payments.

2.26

The NWRN did not oppose the removal of the FAMT from the YA parental

means test, noting that the measure 'dramatically simplifies the existing

test'. However:

...it is true that the test is not as rigorous as the existing

rules for treatment of trusts and companies that were introduced for other

social security payments in 2002 and which are designed to look beyond formal

structures to assess the real value of assets and income that should be

attributed to a person having regard to the level of actual control that person

or their associates have over the decisions of the entity and the sources of

the entities income and assets.[22]

2.27

The NWRN suggested that the Government should capture and analyse data

to evaluate the measure, and if the PIT is not capturing a family's true

wealth, then the definition of 'combined parental income' (on which the PIT is

based) should be amended:

It may ultimately be necessary to add another category of

income to 1067G–F10 something along the lines of "(f) income

attributable to the parent under Part 3.18 (Means Test Treatment of Private

Companies and Private Trusts)".[23]

2.28

ACOSS supported the removal of the FAMT from the YA parental means test

arrangements, provided the provisions relating to income diverted into private

trusts in the broader income support system are extended to dependent YA. ACOSS

explained:

The Family Actual Means Test (FAMT) was introduced to

strengthen the income testing of youth and student payments against income tax

avoidance strategies that were common at the time and have become more

widespread since, including the diversion of personal income into private

trusts and companies, 'negative gearing', and salary sacrifice arrangements.

...

[R]ules were adopted to deal with these income minimisation

practices in the Family Tax Benefit (FTB) and income support payment income

tests. The existing parental income test for Youth Allowance incorporates most

of the FTB provisions. The Bill proposes to remove the FAMT and rely on the

existing parental income test rather than using two separate 'means tests' to

measure family income.

This would simplify the system and improve consistency with

the FTB rules, but would leave one important 'gap' in the parental income test:

minimisation of income through private trusts, which is addressed in the

personal income tests for income support payments but not in the parental

income tests for Youth Allowance or [Family Tax Benefit].[24]

2.29

ACOSS raised this concern in its Budget Analysis 2015–16.[25]

The Department submitted that many of the common mechanisms used to minimise

taxable income are captured by the PIT arrangements for YA:

For example, the major income minimisation strategies–negative

gearing of financial investments and property, salary sacrifices to

superannuation and salary paid as fringe benefits, are included under the PIT.

The components of income currently assessed under the PIT are:

- Taxable income, plus

- Adjusted employer provided benefits, plus

- Target foreign income, plus

- Total net investment losses or net passive business

losses, plus

- Reportable superannuation contribution, plus

- Maintenance received by either parent for the upkeep

of a child in care, and spousal maintenance, less

- Maintenance amounts paid out.[26]

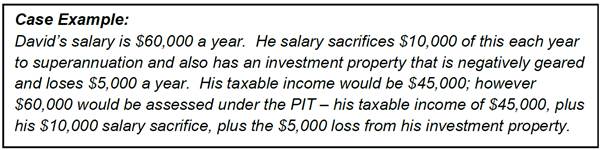

2.30

The Department provided the following example:

Source: Department, Submission 6, p. 12.

2.31

The Department then addressed the situation of family trusts, where

income is allocated to trust beneficiaries and then 'loaned' back to the trust.

The Department advised that such arrangements are captured in either the PIT or

personal income test arrangements:

Distributions to parents from the trust are assessed under

the PIT, even if the funds are loaned back to the trust. This is the same

outcome as under the FAMT.

Where trust income is paid to beneficiaries other than the

parent(s) and the dependent children (for example, an independent adult child),

neither the PIT nor the FAMT would count this as income for the parents as the

amounts involved would not form part of the income, spending or savings of the

family.

If a trust distribution is paid to the dependent young person

it would be assessed under the personal income test.[27]

2.32

The committee understands that the Department has considered income tax

minimisation in relation to the PIT.

Committee view

2.33

The Bill aims to provide more support for families with dependent young

people who qualify for YA and ABSTUDY Living Allowance. As explained by the

Minister, this objective is to be achieved with the removal of 'complex and unnecessary

means tests' and 'improving the operation of the PIT'.[28]

The committee notes that all submitters to the inquiry supported the objective

and provisions of the Bill (with a few exceptions in relation to the FAT and

personal income test).

2.34

The committee notes also that the Bill is consistent with the findings

of an internal review, to simplify the welfare system and align rules for young

people, and responds to the work of an IDC that has engaged in public

consultations (consisting of regional forums) to identify obstacles and

solutions to the enhanced participation of young people from rural, regional

and remote backgrounds in higher education. In

particular, the IDC's preliminary findings include that there are inequities in

the payment of Youth Allowance which is one of the issues that the Bill aims to

address.

2.35

For these reasons, the committee considers that the Bill should be

passed without amendment.

Recommendation 1

2.36

The committee recommends that the Bill be passed.

Senator Zed Seselja

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page