Chapter 2

International and national frameworks

2.1

This chapter outlines the various frameworks under which disability

services are provided in Australia, including:

-

Australia's international law obligations;

-

Commonwealth, state and territory roles and responsibilities;

-

oversight and complaints reporting mechanisms;

- recent disability‑related inquiries and reports; and

-

data collection used to establish the extent of violence, abuse

and neglect against people with disability.

2.2

Australia's compliance with its international law obligations as they

apply to the rights of people with disability (term of reference (f)) is also

examined.

Australia's international law obligations

2.3

Australia is a party to seven core international human rights

treaties—including the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Disability Convention)[1]—and

a number of other international instruments that are relevant to the treatment

of people with disabilities in Australia.[2]

2.4

This inquiry focuses on specific key articles of the Disability

Convention, as this convention generally captures relevant provisions of

these other frameworks as they relate to people with disability:

[T]he Disability Convention does not introduce any new human

rights but instead seeks to redefine disability and make existing human rights

realisable for people with disability by taking account of their experiences

and needs and by contesting pervasive medical and individual models of

disability which have historically encouraged the discriminatory and paternalistic

approaches to rights.[3]

2.5

However, the committee acknowledges the relevance of all international

instruments to which Australia is a party. Those instruments will be

referred to as necessary throughout this report.

2.6

Some of these instruments are not binding in international law: for

example, the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples, the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Violence

Against Women, and the UN Principles for Older Persons. However, this does not

mean that those instruments are irrelevant. Professor Hilary Charlesworth, an

international law scholar based at the Australian National University, has

previously noted:

While General Assembly resolutions are not, strictly

speaking, binding, they are increasingly regarded as a source of international

law. This is particularly the case when resolutions are couched in terms of

obligations of member nations to fulfil their terms. At the very least, resolutions

constitute an important statement of the international, community's views and

contribute to the formation of customary international law.[4]

2.7

The Law Council of Australia, however, noted that where international

instruments are not enacted into domestic law, the realisation of those rights

is fragile:

Whilst the ratification of

international human rights instruments such as the United Nations Convention of

the Rights of People with a Disability (sic) provide a theoretical basis for

the understanding and interpretation of human rights for people with

disability, it does not make them enforceable. In the absence of domestic

legislation implementing such treaties as laws of Australia, the respect for,

and translation of, these rights into practice is neither assured nor likely.

Therefore it is arguable that Australia fails to meet international obligations

regarding rights of persons with disability.[5]

Convention on the Rights of Persons

with Disabilities

2.8

The Disability Convention provides the overarching international

framework for the protection, promotion and fulfilment of rights for people

with disability, and also aims to promote respect for the inherent dignity

of people with disability.[6]

It contains general and specific obligations that apply to States Parties.

Key articles relevant to the terms of reference for this inquiry include:

-

Article 6—Women with disabilities

-

recognises that women and girls with disabilities are vulnerable

to multiple forms of discrimination; and

-

requires States Parties to take all appropriate measures to

ensure that women and girls with disabilities exercise and enjoy the human

rights and fundamental freedoms set out in the convention;[7]

-

Article 7—Children with disabilities

-

requires States Parties to take all necessary measures to ensure

that children with disabilities fully enjoy all human rights and fundamental

freedoms on an equal basis with other children;[8]

-

Article 12—Equal recognition before the law

-

requires States Parties to recognise that persons with

disabilities enjoy legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects

of life; and

-

requires States Parties to take appropriate measures to provide

access by persons with disabilities to the support they may require in

exercising their legal capacity;[9]

-

Article 13—Access to Justice

-

requires States Parties to ensure effective access to justice for

persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others (including promotion of

appropriate training for those working in the field of justice administration);

-

Article 16—Freedom from exploitation, violence and abuse

-

requires States Parties to take all appropriate legislative,

administrative, social, educational and other measures to protect persons with

disabilities, both within and outside the home, from all forms of exploitation,

violence and abuse, including their gender-based aspects;

-

requires States Parties to take all appropriate measures to

prevent all forms of exploitation, violence and abuse by ensuring, for example,

appropriate forms of gender‑ and age‑sensitive assistance and

support for persons with disabilities and their families and caregivers,

including through the provision of information and education on how to avoid,

recognize and report instances of exploitation, violence and abuse.

States Parties shall ensure that protection services are age‑,

gender‑ and disability‑sensitive;

-

States Parties shall ensure that all facilities and program

designed to serve persons with disabilities are effectively monitored by

independent authorities;

-

States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to promote the

physical, cognitive and psychological recovery, rehabilitation and social

reintegration of persons with disabilities who become victims of any form of

exploitation, violence or abuse, including through the provision of protection

services. Such recovery and reintegration shall take place in an environment

that fosters the health, welfare, self‑respect, dignity and autonomy of

the person and takes into account gender‑ and age‑specific needs;

and

-

States Parties shall put in place effective legislation and

policies, including women‑ and child‑focused legislation and

policies, to ensure that instances of exploitation, violence and abuse against

persons with disabilities are identified, investigated and, where appropriate,

prosecuted.

2.9

The committee notes that in signing the Disability Convention, Australia

made a declaration which gives some direction on how Australia interprets the

rights contained in certain articles:

...Australia recognizes that persons with disability enjoy

legal capacity on an equal basis with others in all aspects of life. Australia

declares its understanding that the Convention allows for fully supported or

substituted decision-making arrangements, which provide for decisions to be

made on behalf of a person, only where such arrangements are necessary, as a

last resort and subject to safeguards;

Australia further declares its understanding that the

Convention allows for compulsory assistance or treatment of persons, including measures

taken for the treatment of mental disability, where such treatment is

necessary, as a last resort and subject to safeguards.[10]

Australia's obligations under the Disability

Convention

2.10

The Disability Convention entered into force on 3 May 2008 and the UN Committee

on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN Disability Committee) monitors

its implementation by States Parties. Each State party is obliged to submit

regular reports to the UN Disability Committee, initially within two years of its

ratification of the Disability Convention and thereafter every four years.

The UN Disability Committee examines the reports, and makes observations

and recommendations.

2.11

In December 2010, Australia submitted its initial report, which

was scrutinised by the UN Disability Committee in September 2013.[11]

The UN Disability Committee made a number of concluding observations and

recommendations, in respect of which Australia is due to respond in its

combined second and third report (due in August 2018).[12]

2.12

In general, the UN Disability Committee commended certain initiatives being

undertaken by Australia, but expressed concern with Australia's implementation

of a number of Disability Convention articles. These concerns included whether

Australia was upholding the general obligation to adopt all appropriate

measures for the implementation of rights recognised in the Disability Convention

(Article 4(1)(a)), and the implementation of specific rights in Articles 6, 12,

13 and 16. For example:

The Committee is concerned at reports of the high incidence

of violence against, and sexual abuse of, women with disabilities...the Committee

is concerned about the possibility that the regime of substitute decision‑making

will be maintained and that there is still no detailed and viable framework for

supported decision-making in the exercise of legal capacity...the Committee is

concerned at the lack of training for judicial officers, legal practitioners

and court staff on ensuring access to justice for persons with disabilities, as

well as the lack of guidance on access to justice for persons with

disabilities.[13]

2.13

The UN Disability Committee also commented on 'reports of high rates of

violence perpetrated against women and girls living in institutions and other

segregated settings' and recommended:

...that the State party investigate without delay the

situations of violence, exploitation and abuse experienced by women and girls

with disabilities in institutional settings, and that it take appropriate measures

on the findings.[14]

Comments from submitters and

witnesses

2.14

Submitters and witnesses asserted that Australia was not upholding many

of its international law obligations, primarily under the Disability

Convention, but also under other relevant conventions and instruments.[15]

2.15

Australian Lawyers for Human Rights (ALHR) contended:

Australia has breached international human rights obligations

as they apply to people with disabilities where those people have been

subjected to violence, abuse and neglect in institutional and residential

settings...Critically, these people must be free from exploitation, violence and

abuse, not be subject to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or

punishment and have their physical and mental integrity protected.[16]

2.16

ALHR cited a number of ways in which the rights of people with

disability in Australia are breached, including, but not limited to:

-

people with disability often cannot choose where they live;

-

people with disability are often subject to treatment that may

constitute torture, or cruel or unusual punishment[17];

-

there is a lack of specific legislation or oversight mechanisms

to prevent such treatment;

-

women with disability are subjected to more occurrences of

violence and restrictive practice in residential settings, and face more

obstacles to reporting such occurrences, and

-

the lack of appropriate restrictions on compulsory treatments.[18]

In conclusion, ALHR has grave concerns regarding Australia's

lack of compliance with international human rights obligations provided in the [Disability Convention]. Compliance can be at

best described as poor.[19]

2.17

The Australian Cross Disability Alliance (Disability

Alliance) provided extensive evidence in its submission that many of the

obligations on States Parties contained in the Disability Convention are not

being adequately upheld by Australia. The Disability Alliance further contended

that rights contained in other conventions Australia is signatory to are also not

being realised by people with disability:

Significantly, torture and ill-treatment of people with

disability, including violence, abuse, exploitation and neglect are frequently

subject to commentary in the various concluding observations and recommendations

from United Nations (UN) treaty bodies and the Human Rights Council following

assessment of Australia's human rights performance.[20]

2.18

The Disability Alliance summarised the UN Disability Committee's 2013

review of Australia's performance in relation to the Disability Convention and

found that the UN Disability Committee's key concerns in relation to the

following articles were:

-

Articles 6 and 16: there is a high incidence of violence against

women with disability;

-

Article 7: there is no comprehensive national human rights

framework for children, including children with disability;

-

Article 14: people deemed unfit for trial can be detained indefinitely

without trial, there is an over-representation of people with disability in the

prison and juvenile justice systems, and Australian law allows for people with

disability to be subjected to medical interventions without consent;

-

Article 15: people with disability, are subjected to restrictive

practices such as chemical, mechanical and physical restraints in a range of settings;

and

-

Article 17: Australia continues to allow forced sterilisation.[21]

2.19

The ACT Disability Aged Carer and Advocacy Service (ADACAS) agreed that

the rights of people with disability were not being upheld in Australia:

The interactions we have had with our clients have

highlighted to us the need for greater protection and support of people with a

disability in their interactions with various institutions. The rights of

people with disability are protected in this regard in the Convention on the

Rights of People with Disabilities 2006, which states in Article 16 (1) that:

'States

Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social,

educational and other measures to protect persons with disabilities, both

within and outside the home, from all forms of exploitation, violence and

abuse, including their gender-based aspects.'

It is evident from what we see in our work that this

protection is not been afforded to people with disabilities.[22]

2.20

Action for More Independence in Disability Accommodation argued that the

accommodation restrictions faced by people with disability were also breaches

of Australia's Disability Convention obligations and had flow on effects for

other rights:

In

line with that convention, people with a disability should have the right to a

choice of who they live with and where they live and, further, that people with

a disability should have the right to good quality housing which is accessible,

affordable and non‑institutional, and the right to live in the community

with access to the support they need to participate in the community and have a

good life. These have all been signed up to but have not been delivered on, and

it is our contention that if more work is done to actually deliver on those

convention standards and benchmarks then this will reduce abuse, and that,

after all, is what we would hope to achieve.[23]

2.21

ALHR agreed with this position:

Australia is failing to comply with international human

rights obligations by operating institutions and offering residential settings

which do not allow people to choose who they live with or access services in

the community which are responsive to their needs.[24]

2.22

Ms Mary Woodward, a former disability communications intermediary in the

United Kingdom, provided evidence that she believed Australia's justice system

was not inclusive enough to live up to obligations within the Disability

Convention:

I think that, despite the [Disability Convention] our current

judicial systems do not provide enough modifications for people with

communication difficulties to have a voice in the justice system.[25]

Committee

view

2.23

The UN Disability Committee has commended certain disability-related initiatives

undertaken in Australia, notably the adoption of the National Disability

Strategy, introducing the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), and the

Australian Law Reform Commission's (Law Reform Commission) inquiry into

disability justice issues.

2.24

However, evidence provided indicates Australia has more to do, to ensure

people with disability enjoy full realisation of their rights. The committee

finds the evidence suggests that the institutional nature of some service

delivery contexts contributes to environments that increase the prevalence of

violence, abuse and neglect.

2.25

The committee notes the evidence which indicates Australia has failed to

uphold the rights of people with disability across a number of United Nations

conventions, not just the Disability Convention.

2.26

The committee particularly notes the UN Disability Committee's comments

on the need for improved access to justice for people with disability, more

appropriate decision‑making frameworks and the need for more protection

for women and children with disability. The committee also notes the

recommendation for Australia to close residential institutions and develop

nationally consistent measures for data collection.

Commonwealth, state and territory roles and responsibilities

2.27

Prior to 2009, the Commonwealth had a hands-off role of funding states

and territories to deliver disability services. The Australian Government took

a more proactive role following the signing of the Disability Convention in

2009 and the development of the NDIS. Currently, the Commonwealth, state and territory

governments share responsibility for the provision of disability services in

Australia, with the Australian Government taking a lead role in policy

development and the enforcement of standards.

2.28

The governments' roles and responsibilities are defined in high-level

agreements that have been negotiated in recent years, as governments seek

to address the demand for quality services for people with disabilities. Five

key initiatives are discussed below:

-

National Disability Agreement (NDA);

-

National Disability Strategy, 2010–2020 (NDS);

-

NDIS (formerly known as DisabilityCare Australia);

-

National Plan to Reduce Violence Against Women and their Children

2010‑2022 (National Plan); and

-

National Framework for the Protection of Australia's Children (Child

Protection Framework).

National Disability Agreement

2.29

In November 2008, the Council of Australian Governments (CoAG) agreed

the Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations

(Intergovernmental Agreement). This agreement established the overarching

framework for the Commonwealth's financial relations with the states and territories,

and intends to provide for: increased flexibility in service delivery; a

clearer specification of the roles and responsibilities of each level of

government; and an improved focus on accountability for better outcomes and

service delivery.[26]

Roles and responsibilities

2.30

Schedule F of the Intergovernmental Agreement sets out six

National Agreements that define the objectives, outcomes, outputs, performance

indicators and benchmarks, and clarify the roles and responsibilities, that

guide governments in service delivery across a particular sector.

2.31

One of these National Agreements is the NDA that provides for both separate

and shared roles and responsibilities from 1 January 2009.[27]

The Commonwealth's role is

largely financial and includes:

-

provision of funds to states and territories, to contribute to

the achievement of the objective and outcomes;

-

funding disability services delivered by states in accordance

with their responsibilities under the agreement for people aged 65 years and

over (50 years and over for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples);

-

where appropriate, investing in initiatives to support nationally

agreed policy priorities, in consultation with states and territories; and

-

ensuring that Commonwealth legislation is aligned with national

priority, reform directions and the Disability Convention.[28]

The states and territories' roles and responsibilities are:

-

the provision of disability services (except disability

employment services which are provided by the Commonwealth), including:

-

regulation, service quality and assurance;

-

assessment;

-

policy development;

-

service planning; and

-

workforce and sector development;

in a manner which most

effectively meets the needs of people with disability, their families and

carers, consistent with local needs and priorities;

-

(except for Victoria and Western Australia) funding and

regulating basic community care services for people under the age of 65 years

in line with their principal responsibility for delivery of other disability

services under the agreement, except Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

aged 50 years and over for whom the cost of care will be met by the

Commonwealth;

-

(except for Victoria and Western Australia) funding packaged

community and residential aged care delivered under Commonwealth aged care

programs for people under the age of 65 years, except Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples aged 50 years and over;

-

ensuring that state and territory legislation and regulations are

aligned with the national policy and reform directions; and

-

where appropriate, investing in initiatives to support nationally

agreed policy priorities, in consultation with the Commonwealth.[29]

Commonwealth funding amounts

2.32

Under the Intergovernmental Agreement, the Commonwealth committed

to ongoing financial support for service delivery (clause 19). For the NDA,

this support is provided through general revenue assistance, the NDA Specific

Purpose Payment (NDA SPP) (indexed annually in accordance with defined growth

factors, currently 3.5 per cent),[30]

and National Partnership payments.

2.33

On commencement of the NDA, the Commonwealth committed to total

funding of $5.3 billion over five years for the NDA SPP.[31]

In 2015–16 Budget, the Government

announced that total funding for the NDA SPP in 2014–15 amounted to $1.39

billion. The budget provided for $1.44 billion in 2015–16, with $4.66 billion

in funding over the forward estimates.[32]

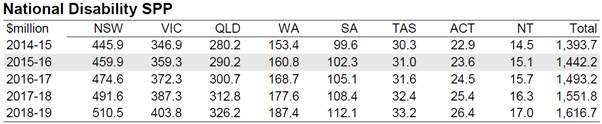

The division of this funding across states and territories is shown in Figure

2.0 below.

Figure 2.1: National Disability Agreement

Specific Purpose Payments, states and territories, 2014–19.

Source: Australian Government, Budget measures: budget

paper no. 3: 2015–16, 2015, p. 40.

2.34

It must be noted that although the NDA states that Commonwealth

legislation must be aligned with the Disability Convention, it does not require

that state and territory legislation must be as well. Clearly this creates a

potential for key parts of domestic law to fail to meet the requirements of the

Disability Convention. Regardless of this, the Commonwealth still retains

the overarching obligation to ensure that all treatment of people with

disability in Australia is in keeping with the rights enshrined in the

Disability Convention, regardless of whether the Commonwealth has explicitly

conferred that obligation in a domestic capacity onto the state and territory

governments.

National Disability Strategy

2.35

In February 2011, CoAG endorsed the NDS, a 10 year national plan that

aims to improve life for people with disability, their families and carers.[33]

It is a collaborative strategy which involves all levels of government. As each

level of government has specific roles and responsibilities across a wide range

of policies and programs, the NDS focuses on creating a more unified approach:

...this is the first time in Australia that a national strategy

articulates long‑term goals across a number of key policy areas which

impact on people with disability, their families and carers. It also provides leadership

for a community-wide shift in attitudes to look beyond the disability.[34]

2.36

The purpose of the NDS is to:

-

establish a high level policy framework to give coherence to, and

guide government activity across, mainstream and disability‑specific

areas of public policy;

-

drive improved performance of mainstream services in delivering

outcomes for people with disability;

-

give visibility to disability issues and ensure they are included

in the development and implementation of all public policy that impacts on

people with disability; and

-

provide national leadership toward greater inclusion of people

with disability.[35]

2.37

The NDS is structured around six broad policy areas, which align with

the principles articulated in Article 3 of the Disability Convention.[36]

Under each of these areas, the desired outcomes and agreed policy directions are

identified, together with areas for future action that are prioritised against

specific timelines in the implementation plans.[37]

Policy Area 2—Rights protection,

justice and legislation

2.38

Policy Area 2—Rights protection, justice and legislation aims to

promote, uphold and protect the rights of people with disability. It has five

policy directions.

-

Policy Direction 3: People with disability have access to justice

Effective access

to justice for people with disability on an equal basis with others requires appropriate

strategies, including aids and equipment, to facilitate their effective

participation in all legal proceedings. Greater awareness is needed by the

judiciary, legal professionals and court staff of disability issues.

-

Policy Direction 4: People with disability to be safe from

violence, exploitation and neglect

There is a range of evidence

which suggests that people with disability are more vulnerable to violence,

exploitation and neglect. People with disability fare worse in institutional

contexts where violence may be more common. People with disability are more

likely to be victims of crime and there are also indications that women face

increased risk.

-

Policy Direction 5: More effective responses from the criminal

justice system to people with disability who have complex needs or heightened

vulnerabilities.

People with disability who have

complex needs, multiple disability and multiple forms of disadvantage face even

greater obstacles within the justice system. There is an over-representation of

people with an intellectual disability both as victims and offenders in the

criminal justice system. Significant rates of acquired brain injury are found among

male and female prisoners. Research into intellectual disability and acquired

brain injury has demonstrated the presence of co-morbidities with mental

illness and substance abuse. This complex profile indicates the need for a

specialist response.

2.39

Future action areas identified for Policy Area 2—such as improving the

reach and effectiveness of complaints mechanisms, and ensuring supported

decision-making safeguards are in place, including accountability of

guardianship and substitute decision-makers—are discussed in more detail in

chapters four, five, and six.[38]

Comments from submitters and

witnesses

2.40

While some submitters and witnesses to this inquiry cited provisions

within the NDS as containing general standards that disability services should

adhere to, few submitters provided any critical analysis of the NDS

itself, with the following exceptions.

2.41

Adelaide People First commented on the lack of strategic implementation:

Another challenge is ensuring the [NDS]

is implemented. The [NDS] has barely rated a mention by anyone with influence

since the 2013 Federal Election. The Federal

Coalition Government has only barely mentioned the [NDS] they haven't explained what it or its purpose in

implementing a holistic approach to disability policy reform. No one in the

broader community even knows of its existence or its purpose.[39]

2.42

First People's Disability Network Australia agreed that implementation

of the NDS had stalled:

I could not agree more that the [NDS] is something that needs

to be reinvigorated and needs a mechanism to oversee it.[40]

2.43

Families Australia and Children with Disability Australia commented that

the NDS did not adequately address the needs of children and young people with

disability.[41]

Committee

view

2.44

The committee is concerned that there appears to be a lack of continued

focus on the NDS. The committee is of the view the NDS should be updated to

bring the framework into line with other relevant protective instruments, together

with a renewed focus on implementation.

National Disability Insurance

Scheme

2.45

Following release of the NDS, governments focussed on developing a

strategic framework for implementing and evaluating the strategy.[42]

In addition, the Australian Government requested the Productivity

Commission (PC) to inquire into a long‑term disability care and support

scheme:

The Productivity Commission inquiry will examine the

feasibility, costs and benefits of replacing the current system of disability

services with a new approach which provides long-term essential care and

support for people with severe or profound disabilities however acquired.[43]

Productivity Commission report

2.46

In August 2011, the PC released its report Disability Care and

Support.[44]

The PC found:

The current disability support system is underfunded, unfair,

fragmented and inefficient, and gives people with a disability little choice

and no certainty of access to appropriate supports.

There should be a new national scheme—the National Disability

Insurance Scheme (NDIS)—that provides insurance cover for all Australians in

the event of significant disability.[45]

2.47

CoAG promptly agreed with the need for a major reform of disability

services through a NDIS and Australian governments immediately began

collaborative efforts to develop the scheme.[46]

2.48

Introduction of the NDIS commenced in two stages at five launch sites:

in Tasmania, South Australia, the Barwon area of Victoria, and the Hunter

area of New South Wales (1 July 2013); and the Australian Capital Territory,

the Barkly region of the Northern Territory, and the Perth Hills area of

Western Australia (1 July 2014).[47]

2.49

The full roll out of the scheme will occur progressively in New South

Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and the Northern

Territory from 1 July 2016.[48]

In the Australian Capital Territory, people with disability are transitioning into

the NDIS based on their date of birth or their academic year (for school

age children), in accordance with a flexible timetable.[49]

2.50

Chapter nine examines the challenges and opportunities presented by the NDIS

rollout in reducing violence, abuse and neglect against people with disability.

National Plan to Reduce Violence

against Women and their Children

2.51

In February 2011, the Australian Government announced the National Plan,

a 12 year strategy endorsed by the Commonwealth, states and territories, to reduce

violence against women and children.[50]

There will be four three‑year action plans, two of which have been

released: the First Action Plan: Building a Strong Foundation 2010–2013

(First Action Plan); and the Second Action Plan: Moving Ahead 2013–2016

(Second Action Plan).[51]

First Action Plan: Building a

Strong Foundation 2010–2013

2.52

The First Action Plan established the groundwork for the National Plan—'the

strategic projects and actions that will drive results over the longer term

while implementing high-priority actions in the short term'.[52]

Each jurisdiction developed its own implementation plan to reflect its

priorities and all jurisdictions collaborated on four joint priorities:

Building Primary Prevention Capacity; Enhancing Service Delivery; Strengthening

Justice Responses; and Building the Evidence Base. For example, all

jurisdictions agreed to work toward development of a comprehensive National

Data Collection and Reporting Framework, to be in place by 2022.[53]

2.53

Key initiatives of the First Action Plan included establishment of

Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety and 1800RESPECT,

Australia's first national professional telephone and online counselling

service for women experiencing, or at risk of, domestic and family violence and

sexual assault.

Stop the Violence project

2.54

In addition, Women With Disabilities Australia (WWDA) was funded to

investigate and promote ways to support better practice and improvements in service

delivery and government responses, to improve the quality of life for women and

girls with disabilities experiencing or at risk of violence (Stop the

Violence project).[54]

A Project Steering Group oversaw the project which examined in detail:

...the prevalence and nature of violence against women and

girls with disability as well as the responses and services available for

addressing such violence. This included the particular susceptibility of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women with disability, and women with

disability who are of culturally and linguistically diverse background, and

women with disability who are of diverse sexual orientation, gender identity or

intersex.[55]

2.55

In October 2013, the Project Steering Group hosted a high-level,

cross-sector National Symposium. In its Report of the Proceedings and

Outcomes, WWDA identified six key thematic areas and two possible

future mechanisms to support the development of good policy and the provision

of good practice in service provision:

-

Area 1—Information education and capacity building for women and

girls with disabilities;

-

Area 2—Awareness raising for the broader community;

-

Area 3—Education and training for service providers;

-

Area 4—Service sector development and reform;

-

Area 5—Legislation, national agreements and policy frameworks;

-

Area 6—Evidence gathering, research and development;

-

Area 7—Establishment and development of a Virtual Centre for the

Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls with Disabilities; and

-

Area 8—Establishment of a National Women with Disabilities Expert

Panel on the Prevention of Violence Against Women and Girls with Disabilities.[56]

2.56

The outcomes of the National Symposium informed the development of the

Second Action Plan.[57]

Second Action Plan: Moving Ahead

2013–2016

2.57

The Second Action Plan channels government efforts toward ongoing and

new priorities, and further engages sectors, groups and communities.[58]

There are five national priorities:

-

Driving whole of community action to prevent violence;

-

Understanding diverse experiences of violence;

-

Supporting innovative services and integrated systems;

-

Improving perpetrator interventions; and

-

Continuing to build the evidence base.

Twenty-six practical actions are identified, with the plan

noting:

These actions are designed to drive national improvements and

most involve efforts of all governments. They will not all necessarily be

progressed by all jurisdictions, or in the same way. Jurisdictions will focus

on local priorities and delivery approaches.[59]

2.58

Under National Priority Two: Understanding diverse experiences of

violence, Action 12 specifically focuses on tailoring responses to meet the

needs of women with disability:

Under the Second Action Plan, governments will work with

expert organisations, including Women With Disabilities Australia to prioritise

and implement key outcomes from the Stop the Violence project. This will

include:

-

bringing together and disseminating good practice information on

preventing violence against women with disability;

-

training for frontline workers to recognise and prevent violence against

women and children with disability; and

-

providing accessible information and support in National Plan

communications.[60]

2.59

The Second Action Plan will be independently evaluated in 2016–2017,

with a key question regarding the effectiveness of the National Plan in

engaging with and supporting women with diverse experiences or who are more

vulnerable to violence (such as women with disability).[61]

National Framework for the

Protection of Australia's Children

2.60

In April 2009, CoAG released the Child Protection Framework which aims

to ensure that Australia's children and young people are safe and well.[62]

To achieve this high-level outcome, governments and the non-government

sector committed to achieving a substantial and sustained reduction in child

abuse and neglect in Australia over time. The Child Protection Framework

identifies the following six supporting outcomes:

-

children live in safe and supportive families and communities;

-

children and families access adequate support to promote safety

and intervene early;

-

risk factors for child abuse and neglect are addressed;

-

children who have been abused or neglected receive the support

and care they need for their safety and wellbeing;

-

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are supported and

safe in their families and communities; and

-

child sexual abuse and exploitation is prevented and survivors

receive adequate support.[63]

2.61

Ms Carolyn Frohmader, Executive Director of WWDA, commented:

So you have these national frameworks and policy frameworks...Then

over here we have the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their

Children. Then we have the National Framework for Protecting Australia's

Children. The National Disability Strategy is not connected to the national

violence plan. The national violence plan is only focused on intimate partner

violence, and does not include institutional settings. The way the

National Disability Strategy addresses violence against people with

disabilities is to say 'make sure we implement the national plan to prevent

violence against women'.[64]

Committee

view

2.62

The Committee notes with some concern, the evidence provided that there

is a lack of cross-over with various national policies and approaches that are

relevant to women and children with disability. The committee is concerned that

there does not appear to be provision for follow-up evaluations of how those

policies are being implemented, or their effectiveness. Of particular concern

is the lack of inclusion of the specific needs of women and children with

disability within mainstream protective frameworks.

Oversight and complaints reporting mechanisms

2.63

As indicated throughout this chapter, there are a number of

international and national policy frameworks that seek to safeguard the rights

of people with disability. Each of these inter-related frameworks has its own

review and reporting mechanisms. However, the states and territories are most

often responsible for the provision of disability services in Australia. Accordingly,

each jurisdiction has its own policy and legal frameworks that are not

necessarily consistent or clear.

2.64

Evidence to the inquiry indicated that the existing oversight and

complaints reporting mechanisms vary considerably state-to-state. Disability

advocates and people with disability described mechanisms that are complicated

and inadequate in terms of access and enforceable outcomes.

2.65

Chapter four presents a detailed examination of the legal and policy

frameworks for reporting and investigating violence, abuse and neglect of

people with disability.

Recent disability‑related inquiries and reports

2.66

In recent years, along with the increased government focus on disability

policy and service delivery, there have been a number of disability-related

inquiries. These inquiries have focussed on matters such as the

vulnerability of people with disabilities to violence, abuse or neglect, the

ability of people with disabilities to access the criminal justice system, and safeguards

within the disability services sector. This section of the report highlights

a few of these inquiries.

In August 2015, the Family and

Community Development Committee tabled its interim report in the Inquiry

into Abuse in Disability Services. Stage 1 of the inquiry examined

Victoria's regulation of the disability services system, and made eight

recommendations on the proposed NDIS quality and safeguarding framework.[65]

The final reporting date is 1 March 2016 and will examine what safeguards are

required in Victoria prior to the transition to the NDIS.

In June 2015, the Victorian

Ombudsman tabled the Phase 1 report in the Investigation into disability

abuse reporting. The report examined the effectiveness of statutory

oversight in Victoria, and concluded that, despite areas of good practice, the

arrangements are 'fragmented, complicated and confusing, even to those who work

in the field'. Consequently, the system is failing to provide coherent and

consistent protection to people with disabilities.[66]

Phase 2 will report late in 2015 and will look in greater depth at the process

for reporting and investigating abuse, drawing on lived experiences.

-

Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC)

In February 2014, the AHRC presented

its report, Equal before the law: towards disability justice strategies.

The AHRC found that access to justice in the criminal justice system for people

with disability who need communication supports, or who have complex and

multiple support needs, is a 'significant problem in every jurisdiction in

Australia', and recommended that each jurisdiction develop an 'holistic, over‑arching'

disability justice strategy.[67]

The committee notes that South Australia is the only jurisdiction so far to

implement a disability justice strategy consistent with this recommendation

(discussed in detail in chapter 6), and the Queensland Department of Justice

and Attorney-General is in the process of implementing a disability service

plan.[68]

-

Victorian Equal Opportunity and Human Rights Commission (VEOHRC)

VEOHRC's report titled Beyond

doubt: the experiences of people with disabilities reporting crime stated

that, in Victoria, people with disability are routinely denied access to

justice and safety, as the criminal justice system is ill‑equipped to

meet their needs. The report identified some significant and complex barriers

to the reporting of crime, noting that people with disability fear that they

will not be believed, or will be seen as lacking credibility, when a crime

is reported to police.[69]

The inquiry into Equality,

Capacity and Disability in Commonwealth Laws examined Commonwealth laws and

legal frameworks that deny, or diminish, the equal recognition of people with

disability as persons before the law and their ability to exercise legal

capacity. The Law Reform Commission noted that most laws relating to legal

capacity are entrenched in state law and considered that the Commonwealth could

model the principles of individual autonomy and independence, as a template for

state and territory reform.[70]

-

Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual

Abuse (RC)

The 2014 Interim Report stated

that children with disabilities are more vulnerable to sexual abuse than

children without disabilities, and are often segregated, to varying degrees,

from the mainstream community for long periods, which increases the risk of

abuse. The RC commented that pre‑employment screening is an important

first step in preventing abuse but screening is not consistent across

Australia. [71] Further,

governments do not agree on whether a national system is appropriate or

feasible.[72]

In August 2015, the RC recommended that states and territories make legislative

amendments to implement a series of standards identified in its working with

children check report, and that the Commonwealth facilitate a national model

for working with children checks.[73]

-

People with Disability Australia (PWDA)

Rights Denied: Towards a

national policy agenda about abuse, neglect and exploitation of persons with

cognitive impairment was a 2009 research study that investigated the

barriers encountered by people with cognitive disabilities, which prevented, or

inhibited, realisation of the human right to freedom from abuse, neglect and

exploitation, and the attainment of appropriate remedies for the violation of

these rights.[74]

2.67

Chapters five and six examine specific aspects of, and recommendations

in, these reports, as well as the committee's views on the need for a national

approach to improving access to justice for people with disability.

Data on violence, abuse and neglect

2.68

The committee notes that there are currently no nationally consistent

data sets available to describe the extent of violence, abuse and neglect of

people with disability. This raises two fundamental problems. First, there is

overwhelming anecdotal evidence of violence, abuse and neglect of people with

disability—made in submissions and during public hearings to this inquiry.

There is a need to formally recognise and quantify the extent of this abuse.

The second issue is that the absence of official nationally consistent data

sets in itself is a critical roadblock to these issues being addressed. Nationally

consistent data on this issue is an essential element to guide long-term policy

development to eliminate instances of violence, abuse and neglect against

people with disability.

2.69

In a summary paper entitled The nature and extent of sexual assault

and abuse in Australia, the Australian Institute of Family Studies notes

that there 'is no standard national data collection that includes the

experiences of sexual violence amongst adults with a disability'. This paper

was only able to identify two findings that shed some light on the extent of

this issue. First, and most startlingly, is that 'women with intellectual

disability are 50–90 per cent more likely to be subjected to a sexual assault

than women in the general population'. Second, in 2007 the Victorian Police

found that over 25 per cent of all sexual assault victims identified as having

a disability.[75]

2.70

The two main surveys conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS) on disability do not collect data on violence, abuse or neglect:

Despite being the major national data collection regarding

the status and experiences of adults with a disability, the ABS Survey of

Disability, Ageing and Carers, does not invite participants to report on their

experiences of violence or abuse. Similarly, the ABS (2006) Personal Safety

Survey report, which specifically investigates experiences of violence, does

not identify the disability status of participants, and the International

Violence Against Women Survey...specifically excluded women with an illness or

disability from the sample for the survey.[76]

This is despite evidence that 'approximately 20 per cent of

Australian women, and 6 per cent of men, will experience sexual violence in

their lifetime'.[77]

2.71

PWDA also noted the shortcomings of these two surveys and also the

General Social Survey conducted by the ABS:

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Personal Safety

Survey (PSS), generally understood to be the most accurate source of national

data about prevalence of violence, does not disaggregate by disability, Indigenous

status or mental illness, and only recruits those currently residing in private

dwellings, excluding institutional residential settings. It also excludes those

who might require some form of communication support—such as some people with

intellectual disability, some Deaf people, some people with hearing impairment,

and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Additionally, it frames its questions around intimate partner violence, thus

excluding the relationships in which people with disability experience

violence.

Similarly, although the General Social Survey (GSS) does

disaggregate by disability status, it also excludes institutional residential

settings. The Disability, Ageing and Carers (DAC) survey does not address any issues

around violence, abuse or neglect, and relies on carers answering on behalf of

people with disability. In all cases, these surveys exclude those who live in

remote areas, which means that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

with disability living in these areas (a cohort who may be at particular risk)

are excluded from the data.[78]

2.72

In correspondence to the committee, the ABS noted that it is currently

undergoing a 'major redesign of [its] statistical collections, methods,

products and services' in order to 'extract greater value from all available

data'. The ABS highlighted that it is collaborating closely with a range of

government agencies and non-government entities on a range of projects. The

committee is most interested in the potential for the National Centre for

Longitudinal Data to commence a longitudinal study of people with disability.

Part of this study could focus on the prevalence of violence perpetrated

against people with disability.[79]

2.73

In the most recent PSS (2012), a disability descriptor question was

included; however, this data did not include people living in institutional

care or differentiate between physical or sexual violence. It is the

committee's view that there is a fundamental need to disaggregate this data

further. The ABS also noted that the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Social Survey is currently collecting information on whether a

person is living with a disability with these statistics being made available

from April 2016.[80]

Whilst the committee reserves its judgement on the adequacy of these

statistics, it commends the ABS on these preliminary steps to collect data that

disaggregates on the basis of disability.

2.74

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare compiles an annual report

titled Child Protection Australia. This publication contains data and

analysis on notifications and substantiations of child abuse and neglect within

the child protection system. Currently this report does not disaggregate data on

the basis of disability. The committee understands that one of the

objectives of the Child Protection National Minimum Data Sets (CP NMDS) is

to 'allow reporting in identified priorities areas (such as disability,

cultural and linguistic diversity and locality)'.[81]

Committee

view

2.75

The committee considers that finalisation of the CP NMDS should be

prioritised as this additional data will be a useful addition to policy makers

and service providers in this area.

2.76

Another dataset that may be helpful in better understanding this issue

is held by the National Disability Abuse and Neglect Hotline. This hotline is

operated through the Department of Social Services (DSS) with its purpose being

to allow callers to report abuse or neglect against both government‑funded

and private organisations. The hotline refers the caller to the most

appropriate body to help resolve the complaint or allegation.[82]

Evidence to the committee suggests that data collected by this service is not

being made available to the community:

The national disability abuse hotline, which now has carriage

under the CRRS [Complaints Resolution and Referral Service], I think, with

People with Disability Australia, data does not go anywhere. The data goes to

government and you are not able to FOI that data...

It is not available via FOI. I know that a number of people

have tried it.[83]

2.77

In its submission to the inquiry, DSS provided a breakdown of the types

of calls it has received since 2012. In the period July 2012 to June 2013,

there were 404 complaints received by the hotline and 346 during July 2013 to

June 2014. The most prevalent complaints were systemic abuse (23 per cent),

physical abuse (16 per cent), psychological abuse (16 per cent), physical

neglect (15 per cent) and emotional neglect (nine per cent). Although this

helps to begin to understand the extent of violence, abuse and neglect that is

perpetuated against people with disability, the submission noted:

It should also be remembered that the Hotline is one of many

ways to report a case of abuse or neglect and that people may be more inclined

to report some types of abuse or neglect compared to others, for example sexual

assaults.[84]

2.78

Despite providing some data to the committee in its submission, Mr James

Christian from DSS acknowledged that the department is selective in what

hotline data is released and who it is released to:

I note that some submissions to the committee have called on

DSS to share data collected by the National Disability Abuse and Neglect

Hotline, a service funded by DSS. DSS recognises that collecting

meaningful data on this issue is a challenge and we are keen to do what we can

to be part of the solution. To this end, our submission includes data from the

hotline, and I trust this has been helpful in your deliberations. DSS does not

routinely publish the hotline data, but we have released data to researchers in

the past and will continue to consider on a case-by-case basis as we receive

those requests. The hotline data has some limitations that must be considered

carefully each time it is used.[85]

2.79

The UN Disability Committee has commented on the issue of data

collection in Australia, and regretted 'the low level of disaggregated data

collected on persons with disabilities and reported publicly' and the 'little

data on the specific situation of women and girls with disability', in

particular those who identified as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

peoples.[86]

It recommended that Australia:

...develop nationally consistent measures for data collection

and public reporting of disaggregated data across the full range of obligations

provided for in the [Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities], and

that all data be disaggregated by age, gender, type of disability, place of

residence and cultural background.[87]

2.80

The UN Disability Committee made similar comments with respect to the

situation of children with disability in child protection data and 'the paucity

of information on children with disabilities, in particular indigenous

children, alternative care for children with disabilities and children with

disabilities living in remote or rural areas'.[88]

Accordingly, it recommended that Australia:

...systematically collect, analyse and disseminate data,

disaggregated by gender, age and disability, on the status of children,

including any form of abuse and violence against children...[and] commission and

fund a comprehensive assessment of the situation of children with disabilities

in order to establish a baseline of disaggregated data against which future

progress towards the implementation of the [Convention on the Rights of People

with Disabilities] can be measured.[89]

2.81

A key initiative of the NDS was the introduction of a periodic report

using trend data to track national progress for people with disability in

Australia.[90]

The first National Disability Strategy Progress Report was presented to CoAG in

2014.

2.82

The committee is particularly concerned by the lack of specific data on

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. The AHRC submitted

that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are significantly affected

by disability compared with the non-Indigenous population and noted that

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with disability experience higher

rates of exploitation, violence and abuse.[91]

2.83

In its 2013 study on indigenous persons with disability, the UN Permanent

Forum on Indigenous Issues found that violence against indigenous women and

girls with disability occurs in schools, at home, in residential institutions

and in disability services.[92]

The study found that available research on Indigenous people with disability:

...shows a serious gap in the implementation and enjoyment of a

wide range of rights, ranging from self-determination and individual autonomy

to access to justice, education, language, culture and integrity of the person.

There are significant unmet needs and rights that are not being addressed, of

which gaps in access to health, life expectancy, educational qualifications,

income, safety of the person and participation in decision‑making are

just a few examples.[93]

2.84

The committee is also concerned by the higher rates of self-harm and

suicide amongst young people with disability. In 2014, the National Children's

Commissioner, Ms Megan Mitchell, in the Children's Rights Report 2014,

stated that children and young people with disability can be disproportionately

affected by intentional self‑harm and suicidal behaviour:

A US study found that 30–64 per cent of children and young

people with an intellectual disability develop comorbid mental health

disorders, a rate of around 3-4 times that of their peers, including higher

rates of depression, anxiety and psychosis. Children and young people with

co-occurring chronic physical and mental health conditions are also said to

have higher probabilities of self-harm, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts

when compared with healthy peers. Research also suggests an association between

chronic pain and suicidality in children and young people.[94]

2.85

The AHRC echoed this view and in its submission recommended that further

research be conducted to validate a link between institutional and residential

settings and intentional self‑harm and suicidal behaviour.[95]

Committee

view

2.86

The committee concurs with the proposition that where data is collected,

it must be in a manner that is 'inclusive of all people with disability'.[96]

Methodologies that exclude people with disability on the basis of where they

live—for example, those in residential or institutional settings, or in

regional or remote locations—or how interviews are conducted—for example,

asking a carer to speak on behalf of a person with disability—is clearly

inappropriate. Exclusion of people with disability from the statistics through

the omission of a disability identifier question is also not appropriate.

2.87

It is the committee's position that where data exists, it should be made

available, albeit in a way that takes into consideration any personal

identifiers. It is also the committee's position that where there is an absence

of data, that it should be a priority for that data to be collected so that the

quantum of violence, abuse and neglect against people with disability can be

fully understood.

2.88

The committee supports the view of PWDA that the lack of data on this

issue undermines the capacity for evidence-based policy development. This will

impact some of the key NDIS policies, such as the quality and safeguards framework

which is currently under development. The role of the NDIS quality and safeguards

mechanism will be discussed further in chapter nine.

2.89

The committee agrees with the AHRC's suggestion that the collection and

publication of disaggregated data could be incorporated into the NDS reports,

and provide a foundation for the development of future implementation plans.[97]

Concluding committee

view

2.90

A number of expert inquiries and reports have been published in recent

years, each looking into specific aspects of disability service provision and

the realisation of rights for people with disability.

2.91

Many of the recommendations from those inquiries and reports were put

forward as being fundamental to the realisation of rights for people with

disability, and essential to Australia meeting its obligations under the

Disability Convention and other relevant human rights instruments.

2.92

The committee remains concerned that there is no timetable from relevant

levels of government for the implementation of these essential measures, and therefore

no foreseeable timetable for Australia fully adhering to the Disability

Convention. The impact this has had on violence, abuse and neglect of

people with disability is highlighted in following chapters of this report.

2.93

The committee also remains concerned with Australia's declaration

regarding reservations on key articles of the Disability Convention.

2.94

The committee is further concerned that key recommendations of the UN Disability

Committee are not being appropriately implemented into Australian law and

practice.

2.95

The committee is also concerned with the lack of reliable statistical

data available for policy development to eliminate violence, abuse and neglect

of people with disability. The use of passive and active exclusion of people

with disability from the statistical record of our country means that issues of

violence, abuse and neglect continue to remain out-of-sight and out-of-mind.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page