Chapter 3 - The nature and extent of illness and disability

3.1

The Committee was informed that the true nature and

extent of illness, disability and death due to toxic dust was difficult to

ascertain. Data sources rely primarily on workers' compensation data which is

limited in scope. While workers in some industries particularly the mining

industry are monitored regularly, this is not the case for all industries. The Construction,

Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) commented that the transient nature of

the construction industry, coupled with the possible delay in developing

symptoms, is an impediment to the accurate compilation of statistics. Many

workers move on to other industries and in some cases lung disease is attributed

to other causes for example, smoking.[60]

Data sources

3.2

Under the National Occupational Health and Safety Data

Action Plan, the National Occupational Health and Safety Commission (NOHSC) maintain

national occupational health and safety data. The primary data source used in Australia

is the National Dataset for Compensation-based Statistics (NDS) which consists

of accepted workers' compensation claims. Datasets are also maintained on

notified work-related fatalities and voluntary notifications of mesothelioma

cases. Other data sources include the National Hospital Morbidity data, the

National Coronial Information System, national surveys of households run by the

Australian Bureau of Statistics and surveys of GPs.

3.3

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations (DEWR)

noted that a review of available data sources shows that there is limited

information on the extent of work-related respiratory disease in Australia.

Estimations of occupational contribution to respiratory disease in society are

difficult because respiratory disease can be attributable to other

non-occupational factors, unless it is specifically related to a unique

workplace causative factor or it can be differentiated by its clinical

features. The information that is available comes from a variety of sources,

including published studies; workers' compensation claims data, the Dust

Diseases Board (DDB) of NSW and the two Surveillance of Australian Workplace-Based

Respiratory Events (SABRE) programs in Victoria

and NSW. Published general practitioner and hospital presentation data sources

do not provide useable information, because respiratory disease cases are

included in categories that also contain such diseases not related to work.[61]

3.4

The Dust Diseases Board of NSW maintains statistical

information gathered from and about individuals who have attended a medical

screening or who have applied for compensation. Information includes:

-

new certificates of disablement issued

categorised by dust disease;

-

deaths categorised by causation and average age;

-

statistics relating to mesothelioma; and

-

medical data on individuals such as x-rays, lung

function tests etc.[62]

3.5

The SABRE project is a voluntary, anonymous

notification scheme of occupational lung diseases. It has been operating in Tasmania

and Victoria since 1997 and NSW

since 2001. It is supported by the Dust Diseases Board of NSW and is being

undertaken in collaboration with the team in London

who developed the Surveillance of Work-related Occupational Respiratory Disease

(SWORD) scheme. It also has links with New

Zealand. The aim of the SABRE project is to

determine the incidence of work-related respiratory disease and inhalation

injury in NSW and Victoria and to disseminate

information about the burden of occupational respiratory disease.[63]

3.6

Other witnesses commented on the lack of comparability

of datasets and the reliance on workers' compensation data. The Australian New

Zealand Society for Respiratory Science (ANZSRS) commented that the need for

consistency of approach in collecting data is becoming increasingly important

as the workforce becomes more mobile. Comparability of data would be in the

interest of gaining long term trending and separating pre-existing trends from

current trends.[64] WorkSafe Western Australia

informed the Committee that it recognised the difficulties associated with

collecting reliable data associated with toxic dust exposure, and it is working

with NOHSC to improve the availability and quality of data according to the NOHS

Data Action Plan.[65]

3.7

Workplace Health and Safety Queensland (WHS) commented

that, in undertaking research for its submission to the inquiry, it had found

it difficult to access data as there was a 'paucity of information of

significance held in a readily accessible form by any organisation, including

the State regulator' in all but the mining industry:

...there have been no identifiable programs for routine

collection of exposure data of the kind which will bring great substance to

these discussions...Industry, probably for reasons related to competition, has

not been motivated or sufficiently organised to fund and set up any scheme for

either data collection or shared data management. This situation applies not

only to those in dusty industries, but to almost all fields where exposure

occurs to hazardous substances with both short and long term health

consequences, but particularly long term exposures with chronic diseases. Only

in mining has there been a long standing arrangement of routinely collecting

dust exposure data by government bodies.[66]

3.8

WHS went on to state that only government seems to be in

a position to command the collection and analysis of data, however:

Efforts to establish such collections of data in Australia

on a national basis through either the National Institute for Occupational

Health and Safety or the NOHSC have come to nought, because of their lack of

continuity. Impartiality and independence in the national arena are now new

considerations. In the case of exposures to respirable crystalline silica, the

time frame must be many decades long. The Health and Safety Executive in the UK

has operated a mechanism into which such critical data from across the nation

can be collected and analysed.[67]

3.9

The Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) also noted that

workers' compensation data lacked detail and timeliness. In addition, a worker

needs to be off work for five days to be included in the workers' compensation

data, whereas the minerals industry records one day off in its statistics. MCA commented

that there is no central database to facilitate analysis, to establish trends

or to track the health of workers as they move from one company to another, or

to track any disease through their life. The data that are available are often

not available in electronic form, so analysis is not easy:

We believe that the focus has been very much on collection

rather than on analysis. In some organisations that do collect data, such as

government agencies, there are cupboards full of material but no resources to

analyse it.[68]

3.10

MCA also referred to the difficulties of tracking the

health of workers and commented that HealthConnect could be a useful means of

monitoring the health of workers in certain industries. HealthConnect collects,

stores, and exchanges health information under strict privacy safeguards. With

amendments to include information on occupation, MCA suggested that tracking

people after they had left the industry could be possible.[69]

3.11

The Australia Institute of Occupational Hygienists (AIOH)

pointed to the Health Watch study of workers in the Australian oil industry. This

is an independent epidemiology program which commenced in 1980. The program

studies the health of about 18,000 past and present employees in the petroleum

(oil and gas) industry. The Health Watch study could be adapted as a model to

study the incidence of occupational disease as a consequence of exposure to

toxic dusts in the workplace (such as exposure to silica in sandblasters).

However, AIOH also commented that the oil industry in Australia is made up of

just a few large, well-resourced companies and an active industry association that

are both able to draw upon occupational hygienists, occupational physicians and

epidemiologists. Most Australians, however, are employed in small to medium

sized enterprises, which do not have access to these levels of resources and as

a consequence, it is difficult to characterise the precise incidence and

prevalence of dust related disease in the general working population.[70]

3.12

Mr Bruce

Ham commented that work had been undertaken

to examine the possibility of a National Mining Health Database. The study

concluded that the current large mining health databases were very similar in

structure and had potential to be combined, especially for research purposes.

However, the existing legislative structures made a central database unlikely. Mr

Ham noted that the research potential of

using existing databases was demonstrated in a joint New South Wales Heart

Disease risk project. A feature of this research was the matching of the

register of miners with the Deaths Index held by the Australian Institute of

Health and Welfare. This has provided an important dataset for further health

outcomes research.[71]

3.13

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) and CFMEU

also highlighted the need for improved data sources. The ACTU recommended

improvements in data collection across the jurisdictions, including

establishing a national medical registry of dust diseases cases. The ACTU

commented that one possible means was to make SABRE compulsory rather than

relying on workers' compensation data:

We need to look at improving the data collection; compulsory

reporting by the states, the jurisdictions, to this scheme; and perhaps

expanding it to the hospitals and GPs and other groups that deal on a daily

basis with people who have contracted airborne diseases. Until that happens we

do not get the right figures and therefore we do not know how big this problem

is and we cannot work out a good strategy, so that is essential.[72]

3.14

The Dust Diseases Board noted that:

The SABRE Scheme plays an important role in determining which

occupations and industries are likely to cause disease and why. Once known,

positive strategies can be developed to prevent lung diseases in these

industries and occupations. The Scheme has the potential to decrease the

incidence of occupational lung disease and to be of significant public health

benefit.[73]

Incidence of disease related to toxic dust

3.15

WHS stated that during the last 100 years, exposure to

dust has resulted in dust diseases which, in Australia,

have claimed thousands of lives and caused some incapacity and suffering to

tens of thousands of others. During the same period, control of dust exposures

following increasingly stringent dust standards has, with the noted exception

of asbestos, reduced present and future incidence of dust disease to a tiny

fraction of that previously observed. WHS commented that the coal mining industry

best illustrates the success of regulation with the prevalence of coalworkers'

pneumoconiosis declining from as high as 27 per cent before World War II and

16 per cent in 1948 to virtually non-existent levels by the turn of the

21st century.[74]

3.16

DEWR provided the Committee with an overview of the estimates

of the incidence of respiratory disease in Australia.

Population based estimates in Australia

are used to indicate the magnitude of premature mortality induced by exposure

to hazardous substances in the workforce. The estimated age-adjusted mortality

rates (expressed in number of deaths per million per year) were estimated to be

5 and 2 for asthma, and 8 and 0 for dust diseases, respectively in men and in

women. However, these estimates only addressed mortality, not morbidity.[75]

3.17

Workers' compensation-based estimates of rates of

work-related respiratory disease are limited as the information published at a

national level only includes cases that result in five or more days off work. A

proportion of respiratory disease cases will not be formally diagnosed or will

occur in workers after they leave work, in which case the connection to work is

unlikely to be established and a workers' compensation claim is unlikely to be

made. Also, a sizeable minority of workers has been shown not to be represented

in Australian workers' compensation statistics.[76]

3.18

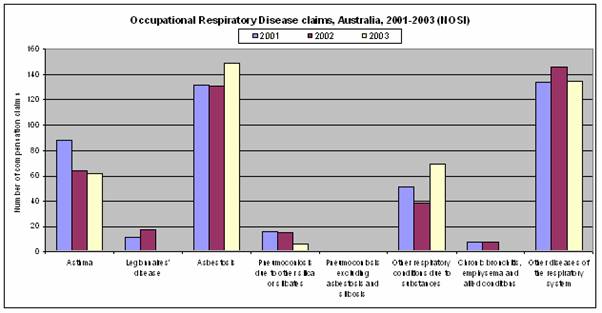

Figure 3.1 shows the numbers of cases of accepted

claims for occupational respiratory diseases in Australia

over the three year period of 2001-2003.

Figure 3.1. Occupational

Respiratory Disease claims, Australia,

2001-2003 (NOSI)

Source: Submission 11, p.6 (DEWR).

3.19

The most common occupational respiratory disease is asbestosis,

followed by asthma. Pneumoconiosis and chronic bronchitis are much less common.

Two of the more common categories are 'Other respiratory conditions due to

substances' and 'Other diseases of respiratory system'. DEWR also provided the

Committee with a breakdown of 'other respiratory conditions due to substances'

showing the number of accepted compensation claims against a causal chemical

agent. For example, industrial fumes and gases had 225 accepted claims from

1996-97 to 2003-04 while there were 635 claims for 'dust not elsewhere classified'.[77]

3.20

The three industries with higher disease claims are

manufacturing followed by education, and health and community services. In

manufacturing, asbestos related-disease is the main disease group (233 claims),

with asthma in the second group (59 claims). In education and health and

community services, claims are mainly in the 'Other diseases of the respiratory

system' group. When considering occupation groups, the higher number of claims

occur in professionals, associate professionals and labourers respectively.

Most claims occur in 'Other diseases of the respiratory system' for

professionals, while most claims for associate professionals and labourers are

asbestos-related disease.[78]

3.21

Table 3.1 shows the number of workers and dependents

who received compensation under the NSW dust diseases scheme during 2004-05.

Table 3.1: Compensation payments during 2004-05 by disease for the NSW

dust diseases scheme

|

Disease |

Workers |

Dependants |

TOTAL |

|

Asbestosis |

230 |

308 |

538 |

|

Silicosis |

188 |

276 |

464 |

|

Byssinosis |

2 |

7 |

9 |

|

Hard Metal

Pneumoconiosis |

3 |

2 |

5 |

|

Farmer's

Lung |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Aluminosis |

2 |

1 |

3 |

|

Bagassosis |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Asbestos

Related Pleural Disease (ARPD) |

449 |

112 |

561 |

|

Silico-Tuberculosis |

1 |

9 |

10 |

|

Asbestosis/ARPD |

63 |

23 |

86 |

|

Talcosis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Silico-asbestosis |

4 |

2 |

6 |

|

Mesothelioma |

226 |

1244 |

1470 |

|

Lung

cancer associated with silicosis |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Silicosis/ARPD |

2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Carcinoma

of the Lung* |

20 |

85 |

105 |

|

Silica/Lung

cancer |

5 |

16 |

21 |

|

Silicosis/mixed dust

fibrosis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

|

Plueral plaques &

pain |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Mixed dust with

pneumoconiosis |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

Lung cancer in

association with asbestos exposure |

12 |

100 |

112 |

|

Peritoneal mesothelioma |

16 |

46 |

62 |

|

TOTAL |

1226 |

2235 |

3461 |

* includes

Hexavalent chromium associated lung cancer, asbestosis/lung cancer & ARDP/lung

cancer

Source: Dust

Diseases Board of NSW, Making a

Difference Annual Report 2004/2005,

Appendix 5, p.70.

3.22

Table 3.2 shows data published by the Dust Diseases

Board of NSW on deaths by causation and average age since the inception of the Workers'

Compensation (Dust Diseases) Act on 29

February 1968.

Table 3.2: Deaths according to disease for the NSW dust diseases scheme

since 1968

|

Disease |

Death due to dust |

Death not due to dust |

Total |

Average age of death due to dust |

|

Asbestosis |

402 |

241 |

643 |

72.57 |

|

Silicosis |

435 |

944 |

1379 |

70.98 |

|

Byssinosis |

11 |

19 |

30 |

71.83 |

|

Hard Metal Pneumoconiosis |

2 |

3 |

5 |

63.43 |

|

Farmer's Lung |

1 |

2 |

3 |

61.17 |

|

Aluminosis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

- |

|

Bagassosis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

- |

|

ARPD |

168 |

89 |

257 |

75.70 |

|

Silico-Tuberculosis |

8 |

12 |

20 |

62.80 |

|

Asbestosis/ARPD |

32 |

25 |

57 |

76.83 |

|

Emery Pneumoconiosis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

- |

|

Talcosis |

1 |

2 |

3 |

65.74 |

|

Silico-asbestosis |

10 |

4 |

14 |

67.31 |

|

Mesothelimoa |

1812 |

8 |

1820 |

67.98 |

|

Peritoneal Mesothelimoa |

2 |

0 |

2 |

63.45 |

|

Carcinoma of the Lung* |

213 |

2 |

215 |

68.69 |

|

Silicosis/Lung Cancer |

25 |

0 |

25 |

71.41 |

|

Silicosis/Mixed Dust Fibrosis |

3 |

0 |

3 |

72.60 |

|

Mixed Dust Pneumoconiosis |

1 |

0 |

1 |

61.47 |

|

Lung Cancer in Association with

Asbestos Exposure |

109 |

4 |

113 |

68.35 |

|

TOTAL |

3235 |

1358 |

4593 |

68.37 |

*

includes Hexavalent Chromium Associated Lung Cancer, Asbestosis/Lung Cancer and

ARPD/Lung Cancer

Source: Dust

Diseases Board of NSW, Making a

Difference Annual Report 2004/2005,

Appendix 5, p.70.

3.23

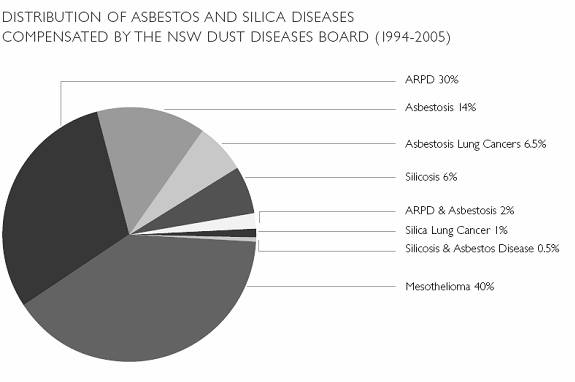

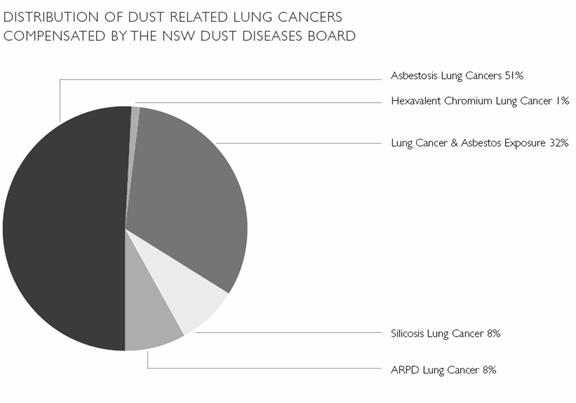

The Dust Diseases Board also provides information on

the proportion of compensation payments made for asbestos and silica diseases

and all lung diseases. Figure 3.1 shows that asbestos-related compensation

accounted for 90 per cent of the compensation payments made by the Board from

1994 to 2005. Silicosis lung cancer accounted for 8 per cent of the dust

related lung cancers compensated by the Board in the same period.

Figure 3.1: NSW Dust Diseases

Board Compensation payments 1994-2005

Source: Dust Diseases Board of NSW, A

Guide to Compensated Occupational Lung Disease in NSW, p.15.

3.24

Information from the Dust Diseases Board only shows

data for cases where compensation has been paid. Therefore, these figures do

not include other lung diseases or other diseases caused by occupational

exposure to dust, or unsuccessful cases for compensation.

3.25

A further source of data is the SABRE notification

scheme. For Victoria and Tasmania,

the most common condition reported by physicians is asthma (33 per cent of

occupation respiratory events reported). The asthma incidence rate is 30.9 per

million workers per year with a 2.4 times higher incidence rate in men compared

to women. However, DEWR noted that SABRE in Victoria

and NSW has incomplete coverage of physicians who see cases. The two most

commonly reported causative agents for asthma in the SABRE (Victoria)

notification scheme are wood dust and isocyanates (13.5 per cent and 5.8 per

cent respectively). The finding of asthma as the most commonly reported

occupational respiratory disease is similar to that found in overseas physician

notification schemes. The next most commonly reported condition in Victoria

and Tasmania is non-malignant

pleural disease from asbestos exposure.[79]

3.26

DEWR also provided rates compensation and

hospitalisation arising from inorganic dusts other than asbestos. For pneumoconioses

other than asbestos, there was a decrease in the hospitalisation rate. This may

be because the curves reflect different time periods in the history of the

disease; or there may be better treatment available, which means less

hospitalisation. In 2001-02 there were 72 hospitalisations, with 20

workers' compensation cases accepted. The hospitalisation numbers may include

the same individual presenting for multiple hospitalisation during the year. Workers'

compensation cases slightly increased, from 1.8 cases per million employed in

1998–1999 to 2.2 cases per million employed in 2001-02.[80]

3.27

While asbestos exposure in the workplace has decreased

over the last 40 years, asbestos related disease has a period of long

latency and it has been estimated that the incidence of asbestos related

disease will continue for the next ten to fifteen years. Data provided by DEWR

showed that asbestos-related workers' compensation cases increased from 10.1

cases per million employees in 1998-99 to 16.0 cases per million employees in

2001-02. Compensation cases for mesothelioma during the same period increased

from 5.4 cases per million to employees to 7.4 cases. Hospitalisations for

mesothelioma were higher.[81]

Incidence of disease related to

exposure to respirable crystalline silica

3.28

Submissions noted that health problems associated with

exposure to crystalline silica dust have been under investigation and control

in Australia

for more than a century. In 1905, investigation of the hard rock mining

industry in Western Australia was

carried out. In 1914 a Royal Commission was appointed to investigate safety

issues in Broken Hill mines. Surveillance by the NSW Silicosis Board (now the

Dust Diseases Board) and NSW Health Department resulted in the investigation

and control for Sydney

sandstone workers.[82] Regulations to

control dust disease were enacted in Western Australia

and New South Wales by the 1920s.

Dust disease was largely due to silica dust and tuberculosis.[83]

3.29

An exposure standard was set for silica in 1983-84 with

the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) recommending exposure

standards specifically for quartz (0.2 mg/m3), cristobalite (0.1 mg/m3) and

tridymite (0.1 mg/m3). In 1988 the exposure standard was reconsidered and a

reduction to 0.1 mg/m3 for respirable fraction of quartz, silica (fused) and tripoli

and 0.5 mg/m3 for cristobalite and tridymite was recommended. Following

public comment, it was agreed that further examination of the issue was

warranted. Between 1988 and 1996 no formal national exposure standard for

crystalline silica existed although some mining and OHS authorities issued

their own. From 1996, NOHSC reinstated the original NHMRC exposure standard. On

1

January 2005, a

revised national exposure standard of 0.1 mg/m3 for

quartz, cristobalite and tridymite came into effect.[84] (The new exposure standard is

discussed further in chapter 5).

3.30

While regulations were introduced to control silica

dust and appear to have had an impact on silica-related disease, NOHSC has

noted that 'due to a long lag time between exposure and symptoms, it is

difficult to ascertain how many people develop silica-related conditions, and

when the causative exposure occurred'. In addition health statistics do not

readily identify health problems related to exposure to RCS due to poor diagnosis

and lag times and, as noted above, compensation data relates only to cases for

which compensation has been paid.[85]

(Diagnosis of dust related health problems is discussed in chapter 4).

Silicosis

3.31

It was acknowledged in evidence that regulation has had

an impact on the exposure of workers to RCS, however, there was considerable

discussion on the incidence of silicosis in Australia

today and the incidence in particular industries. Some witnesses stated that

silicosis was now not a problem while other witnesses argued that silicosis was

'the new asbestosis'.

3.32

Witnesses pointed to a number of reviews and research

papers on the incidence of silicosis which indicated a decrease in the number

of cases of silicosis. In 1993, a review by the National Occupational Health

and Safety Commission of the state by state silicosis records indicated that

there were probably less than 20-30 new cases per year and the generality was that

these cases arose from uncontrolled exposure situations (that is, industries

and occupations where there was minimal or negligible adherence to the

legislative exposure standard and control requirements).[86]

3.33

Reviews of data on new cases of silicosis from the

mining industry have indicated that the incidence of silicosis has fallen. In Western

Australia, for example, there were only three cases

where the person had commenced employment after 1968 and none after 1994. It

was concluded that the absence of cases 'corresponds to the implantation of the

0.2 mg/m3 respirable

crystalline silica exposure standard in Western Australia...when the new cases

still arising as a legacy of the past have all been accounted for, new

incidences of this disease will have been virtually eradicated.'[87] Coal Services NSW also noted that for

the last decade there had been no incidence of silicosis that has been brought

to its attention. This reflected the safety management of companies and the

educational program that has been given to coalminers.[88]

3.34

AIOH also commented

that a review of the statistics commissioned by Worksafe Australia

in 2004 substantiated the small number of new cases of silicosis arising from

Australian industries.[89]

3.35

WHS also provided a review of known compensable cases

of silica related disease in Queensland.

Between 1992 and 2004 there were six claims for silicosis provided by the

Queensland Employee Injury Data Base. WHS stated that the evidence related to

incidence of compensable silicosis is rare and extremely limited for Queensland

workers as a whole and for abrasive blasting workers in particular.[90] It noted that some early exposures to

crystalline silica (prior to 1995) in sandblasting are likely to have been

excessive in modern day terms, though the compensation data do not reflect any

cases of silicosis.[91]

3.36

AIOH noted that silicosis numbers had declined. This

was due to a combination of regular medical surveillance, and reduction in

exposures such as compliance with a regulatory exposure standard, the

prohibition of specific tasks associated with high risk (such as sandblasting

and the use of silica flour in foundry operations) and the use of adequate dust

suppression systems such as ventilation and wetting down.[92] AIOH concluded:

Media headlines often imply that silica is "the new

asbestos". However examination of the data suggests otherwise. Silica has

been under surveillance for many decades, and the morbidity and mortality of

large populations of heavily exposed individuals have also been studied over

many decades. Clinical silicosis is now a rarity, and elevated risk of lung

cancer appears to be confined to cases where the silica exposure is of such a

level that it results in clinical silicosis. Based on the number (say 10-30) of

new cases of silicosis, this would amount to only 1 or 2 additional lung cancer

cases per year across Australia.[93]

3.37

The Cement Concrete and Aggregates Association (CCAA)

also stated that in the heavy construction materials industry 'even very early

or mild cases have been very rarely seen in this industry over the past 10

years. Those which have been diagnosed in that time all result from exposures

from at least 10 years ago.' CCAA concluded:

It is CCAA's view that in the heavy construction material

industries, substantial reduction of potential exposure has occurred, with

predicted and proven advances in dust control. In addition, the improved use of

personal respiratory protection has also reduced the risk of silicosis to

workers to its present extremely low level in Australia.[94]

3.38

Dr John Bisby remarked that in Australia in the last 50

years silicosis 'has been a fairly mild disease...But it can cause incapacity, so

it may reduce quality of life as opposed to reducing life expectancy, although

it can reduce life expectancy particularly in severe cases'.[95] Dr

Bisby, while conceding problems in certain

instances like sandblasting, also stated:

The silica issue is, in medical terms, basically over. It is a

great success story. Australian industry is free of silicosis, by and large.

That is not to say an occasional case may not happen, just like a truck

accident happens when somebody does the wrong thing. Basically it is

historical.[96]

3.39

Professor E

Haydn Walters

responded to this evidence and stated that:

I suppose it is true as far as it goes, I would say. In very

well regulated industries in which the conventional standards of dust exposure

are maintained, I would agree that interstitial lung problems, the traditional

pneumoconiosis, are now probably largely a historic issue. However, I think

those industries where the regulations are not vigorously upheld – and I think

a number of people have made rather off-the-cuff comments about cowboys in sandblasting

and that sort of stuff – still exist, and silicosis will still appear in time

because it is related to the amount in the atmosphere and the length of time

that you are exposed. If you are above the current threshold, then I think you

are still in danger of getting silicosis.[97]

3.40

In its Regulation Impact Statement, NOHSC sounded a

note of caution on the impact of the then exposure standard:

As diseases caused by exposure to RCS are of long latency,

current cases of adverse health effects could reflect the effect of past

exposures, when exposures were potentially greater than they are now under the

current standard. Therefore current cases may be an over-estimate of the effect

of the current NES [National Exposure Standard].

Conversely, the current NES...may be achieving their objectives,

which is why there are few incidents of adverse health effects recorded in

statistics. In addition, this could be a reflection of the under-reporting of

adverse health effects resulting from RCS exposure in official health

statistics.[98]

3.41

Other witnesses commented that silicosis is still a

significant disease. The CFMEU pointed to data from the Dust Diseases Board

which indicated that there were 200 cases each year and 'those are the ones

that are actually accurately diagnosed by the medical profession as having

silicosis'.[99]

3.42

Munich Holdings of Australasia provided the Committee

with a recent publication from the Munich Re Group on the impact of silicosis.

The paper noted that US insurers had been observing an increase in

silica-related claims. It was also noted that while claims were rising

strongly, the number of deaths from silicosis is declining steadily which

reflected the increased workplace safeguards from the 1970s on.[100]

3.43

Other researchers have also stated that 'it is

generally well known that the majority of workers exposed to crystalline silica

in Australia

work outside the mining industry'.[101]

The particular concerns of sandblasting were raised in evidence. WHS stated

that there was some evidence that during the period up to the late 1980s that

some silica exposures would have been occurring during abrasive blasting

operations which did not comply strictly with the regulatory requirements of

the time. WHS also commented that:

How much the silica dust exposure which did occur during the

1960s, 70s and 80s is likely to have contributed to silicosis cannot be fully

identified as reliable compensation statistics have been provided only as far

back as 1992. Given that the latency of silicosis will be around 20 to 30 years

(depending on years of first exposure and other factors), radiological

confirmed cases ought to have been appearing from 1990 through to the present.[102]

3.44

There are now various prohibitions in place relating to

free silica in abrasive blasting (NSW, WA, Tasmania); more than 5 per cent free

silica in abrasive blasting (SA, WA, Tasmania, NT) and more than one per cent

crystalline silica for abrasive blasting in Victoria and 2 per cent in Western Australia.[103] Mr

Nickolas Karakasch

noted that the United Kingdom

was one of the first countries to prohibit sandblasting. NSW prohibited sandblasting

in 1959, with the other States following some time later. Victoria

did not prohibit this activity until 2002.[104]

Blasting media that could be substituted include garnet, metal shot and

aluminium oxide.

3.45

Mr Karakasch

also stated that a 1987 report by the International Agency for Research into

Cancer (IARC) indicated that sandblasters in the USA

had the highest potential exposure to silica content of respirable dust. This

ranged from 4.8 – 12.2 per cent. Mr Karakasch

concluded:

Considering the sandblasting methods in Australia

and throughout the world were basically the same, it would not be unreasonable

to assume that sand blasters throughout Australia

were exposed to similar levels as reported in the 1987 USA

report. In comparison to the Victorian figure it is between 5 to 12 times the

allowable limit.[105]

3.46

AIOH also commented that the impact of the prohibition on

eliminating the use of silica/silica containing materials in sandblasting is

unknown. However they pointed to a 2001 report on the results of a blitz by the

Department of Workplace Health and Safety on abrasive blasting operations

throughout Queensland. This survey

found that of 49 operations audited, two (4%) were using dry sand. Other

than the two (4%) using sand, they also found that garnet was used as a

major blasting medium while others used ilmenite, different types of metal

refinery slags and metal shot. One operator used sodium bicarbonate. A small

number were using glass. WHS concluded that 'use of quartz bearing sands is now

low, but the 2 cases observed were found to contain silica between 58 – 78%

free silica. These operations were issued with Prohibition Notices.'[106] AIOH also commented that most

industries are now using substitutes such as garnet.[107]

3.47

AIOH provided details of a review of silicosis

sufferers who had received compensation in NSW. This showed that only just over

one per cent (less than one case per year) of people, who were receiving

compensation prior to 1970 and were still alive in 1970 and those who were

awarded compensation from 1970 to 1994, indicated that they did sandblasting as

part of their work. Most of these sandblasting cases were exposed around 1970

or earlier.[108]

3.48

CCAA commented on the unsatisfactory practices in some

industries and stated that 'the level of exposure that an unprotected

sandblaster might be exposed to is several hundred times the level of the

standards'.[109]

Airway disease

3.49

Professor Trevor

Williams concurred that there had been

'substantial reductions in classic silicosis'. However, he stated that 'it has

become apparent...that a new pattern of disease is emerging'.[110] People who have been exposed to

silica are now presenting with diseases including obstructive lung diseases and

pulmonary fibrosis. There is also propensity for dust such as silica to

increase the risk of the development of lung cancer and stomach cancer. He

commented:

I am also concerned that many patients with so called idiopathic

pulmonary fibrosis may have the genesis of their disease in exposure to fine

dust such as silica and that causal link is not made because of a long delay from

exposure to overt disease.

I don't believe we have sufficient information to even start to

understand the extent of these problems in Australia

and well designed studies are urgently needed.[111]

3.50

Professor Walters

also raised concerns about the incidence of COPD due to dust. He stated that the

contribution of dust, particularly in occupational settings, to subtler forms

of respiratory disease, and particularly to COPD, has been ignored. The

Professor also stated that as cigarette smoking becomes less, and also as more

vulnerable groups, particularly women, move into the workplace, the impact of

these dusts upon airway disease and the acceleration of the natural ageing

process of the lungs by exposure to dust is now becoming a significant feature,

and that is not being represented.[112]

3.51

The Professor informed the Committee that research data

are emerging that shows that these conditions of COPD related to dust,

particularly in the workplace, are perhaps more common than people have thought.

Research published in June 2005 in the journal Thorax by Professor Walters

and a research group in Victoria

found in a random survey of 4 000 or 5 000 people working and living

in the suburbs of Melbourne,

aged between 45 and 65, that there was about 10 per cent COPD in the

population. The Professor stated:

...particularly amongst the women, it was quite evident that

occupational exposure, particularly to biological substances but also to

mineral dust, was having an impact. It was a fairly subtle impact, but a

definite statistically significant impact upon their lung function. That

included people like nurses and those working in bakeries and so on who were

exposed to dust.[113]

3.52

However, AIOH commented that removing the smoking

component from airways disease and the reduced contemporary silica dust

exposures would mean only a few additional cases of airways disease per year in

Australia.[114]

Costs associated with adverse

health effects

3.53

NOHSC, in undertaking the review of the crystalline

silica exposure standard in 2004, provided costs associated with adverse health

effects. It was estimated , using NSW and national data, that the annual cost

of disease related to past exposure to crystalline silica in Australia

is in the order of:

-

$14,022,857 in compensation payments (including

medical costs, an indicator of potential cost) per annum;

-

305 hospital days per annum; and

-

60 lives per annum.[115]

NOHSC noted that health statistics used did not include

non-fatal conditions, such as disease or a restriction of function that does

not result in hospitalisation as these data are not available.[116]

Incidence of disease associated

with beryllium

3.54

Workers in Australia

have been exposed to beryllium dust. However, Mr

John Edwards

commented that the number who may have Chronic Beryllium Disease (CBD) is

unknown as until very recently there has been no dedicated Beryllium Blood

Lymphocyte Proliferation Testing (BeLPT) laboratory.[117] Workers most at risk are those in

the aviation industry as well as Navy personnel as a result of the descaling of

ship surfaces and workers in the alumina industry.[118]

3.55

In the United States,

the Department of Energy (DOE) is compensating DOE workers for exposure to

airborne beryllium. As at March 2006 DOE had approved 3034 beryllium claims and

paid out US$303.5 million in worker compensation in addition to $91 million in

medical costs. Mr Edwards

argued that the exposure of Australian workers to dusts, fumes and aerosols

containing beryllium materials is no different from the USA

so that cases are expected to be identified in Australia

with the establishment of a testing laboratory.[119]

Conclusions

3.56

Evidence received by the Committee points to a need to

improve the data available for identifying the incidence of disease related to

toxic dust. At the present time, there is a lack of comparability of datasets

and a reliance on workers' compensation data which may not indicate the true incidence

of toxic dust-related disease in Australia.

Workers' compensation data only includes those workers who have had five or

more days off work with a successful claim of a work-related illness. Where

diagnosis occurs after a worker has left work, the connection to work is

unlikely to be established and a workers' compensation claim is unlikely to be

made. This may lead to significant under representation of dust disease.

3.57

Witnesses called for a more comprehensive collection

system including the establishment of a national medical registry of dust

diseases cases. A national registry would assist in tracking workers as they

move from job to job. It would also provide more timely data to improve identification

of trends in disease. One possible means suggested to the Committee was to make

the SABRE system compulsory.

3.58

The Committee agrees that there is need to improve data

collection. Without reliable data, the true extent of dust-related disease is

unknown, trends cannot be identified in a timely manner and decision-making by

government, industry, unions and the medical profession is hampered.

Recommendation 1

3.59

That the Australian Safety and Compensation Council

review the National Data Action Plan to ensure that reliable data on disease

related to exposure to toxic dust is readily available.

Recommendation 2

3.60

That the Australian Safety and Compensation Council extend

the Surveillance of Australian Work-Based Respiratory Events (SABRE) program

Australia-wide and that the program provide for mandatory reporting of

occupational lung disease to improve the collection of data on dust-related

disease.

3.61

The incidence of toxic dust-related disease in Australia

today was debated extensively in evidence. Some witnesses commented that cases

of silicosis now emerging reflect past exposures and past work practices and

that silicosis is now a mild disease. However, other witnesses argued that

silicosis is the 'new asbestosis'. The Committee acknowledges that while the

data may under represent the incidence of disease, the available data suggests

that systems now in place to control dust related disease, particularly

silicosis, appear to have had a positive impact on the incidence of disease. Workers'

compensation cases of pneumoconioses other than asbestosis have increased only slightly

since 1998-99 from 1.8 cases per million to 2.2 cases per million in 2001-02.

3.62

However, the Committee notes that with apparently low

mortality from exposure to toxic dust, the economic cost of this level of

disease is still significant. NOHSC estimated in 2004 that compensation costs

for disease related to exposure to crystalline silica is in the order of $14

million per annum. The compensation costs for asbestos are substantially

higher. Compensation costs related to exposure to other dusts such as beryllium

are unknown but may be significant in the future.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page