Chapter 4

Vertical fiscal imbalance

4.1

One of the challenges faced by governments in all federations is that

over time the financial costs of providing services tend to shift between the

different levels of government. Unless financial adjustments are made, the

constitutional responsibilities of one level of government can become

misaligned with the capacity of that government to raise revenues needed to

meet financial demands made upon it. If the misalignment becomes too

substantial it can have serious consequences for the way the federation

operates, with constitutional balances of power shifting often without formal

constitutional reform. This chapter examines this issue in the context of the

Australian federation.

4.2

The difference between the shares of revenue collection and of

expenditure among various tiers of governments is called the 'vertical fiscal

gap' or, in Australia, vertical fiscal imbalance' (VFI). VFI can exist between

any two levels of government. In some countries, the VFI is most marked between

national and regional governments (for example in Australia, Canada and India) while

in others it can also be between national and local governments (for example in

Brazil, Germany and the United States). In theory, there could be a VFI in

which a lower tier of government collects more revenue than it expends, and

transfer funds to a national government. In practice this never occurs. It is

always the national government that gathers most revenue, and then transfers it

to the state and local levels.

4.3

It is a commonly held belief among political practitioners within

federations and academic theorists of government that excessive levels of VFI

are undesirable. Among other things it creates inefficiencies, undermines

accountability between different tiers of government, reduces fiscal

transparency and can result in the misallocation of resources. As a result most

federations have developed sometimes highly complex intergovernmental arrangements,

involving transfers of large amounts of revenue to one or other tier of

government in an effort to remedy the problem. The size and conditionality of

the transfers are almost always controversial and lead to significant criticism

of the system.

VFI within the Australian federal system

4.4

The Australian federal system is characterised by a significant level of

VFI. Twomey and Withers have argued that 'some VFI is not unusual in a

federation' but go on to note that 'its extent in Australia is the most extreme

of any federation in the industrial world.'[1]

Data collated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(OECD) indicates the degree of VFI within the Australian federal system

compared with other federations.

Figure 4.1: The vertical fiscal imbalance: a comparison

with other federations in per cent of total sub-national revenue[2]

4.5

In considering Australia's VFI, it should also be noted that the extent

of the VFI varies depending on the assessment of the Commonwealth's revenue

raising capacity. The OECD data notes that Australia's VFI increased with the

introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (the GST). This was also noted in

evidence to the committee.[3]

Australia only has a large VFI if one treats the GST as Commonwealth revenue.

Although legally accurate, as all of the revenue is distributed to the states

and territories, including the GST when calculating the VFI is a distortion of

the fiscal reality. Nevertheless, Australia's VFI is significant and

entrenched.

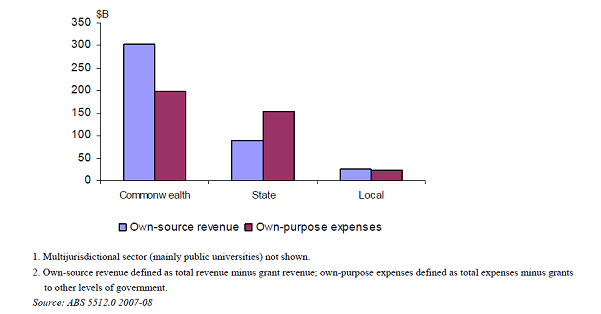

4.6

The chart prepared by CAF demonstrates the disparity in the Australian

federal system between revenue raising capacity and expenses across the levels

of government.

Figure 4.2: Commonwealth, state and local government

revenue and expenses[4]

4.7

Australia's high level of VFI is not a recent phenomenon; it has been a

characteristic of the federation for many decades and has led to the

development of an extensive range of mechanisms to try to address the problem.

Managing VFI within the Australian federation

4.8

As the Commonwealth raises more revenue than the states and territories,

these mechanisms all involve the Commonwealth transferring funds to the states

to assist them to meet their expenditure responsibilities. As explored in

chapter five, this is known as 'fiscal equalisation'. The different capacities

of the states and territories to raise revenue has meant that their expenditure

requirements are taken into account when allocating payments.[5]

As Twomey and Withers have noted, while Australia has significant VFI balancing,

this is due to the fact that Australia 'also happens to have the highest level

of fiscal equalisation.'[6]

4.9

Measures that have been introduced to attempt to improve the fiscal

imbalance between the tiers of government include GST distribution, Specific

Purpose Payments (SPPs), National Partnership Payments (NPPs) and general

revenue assistance.

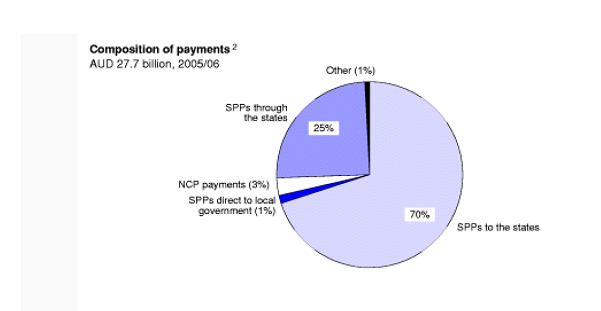

4.10

Prior to the IGA on Federal Financial Relations, discussed below, the

Commonwealth provided financial assistance to the states and territories

primarily in two forms: general revenue assistance – mainly GST revenue[7]

and Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs).[8]

Data provided by the OECD indicates the measures that existed as of 31 July

2006.

Figure 4.3: Measures to address VFI in Australia as of 31

July 2006[9]

4.11

Commenting on these measures, the OECD concluded that:

[a] simpler system of inter-governmental transfers involving

so-called “specific-purpose payments” would contribute to a clearer

specification of spending responsibilities. The specific-purpose payments

should become less complex and inflexible. A first step would be to develop an

outcome/output performance and reporting framework for each SPP. This is an

ambitious task as outcome/output measures of service delivery are difficult to

clearly define, measure and enforce in a robust way. Nevertheless, such

frameworks could ultimately lead to a move towards the funding of such payments

on an outcome/output basis in certain areas.[10]

4.12

On 26 March 2008, COAG agreed to a new microeconomic reform agenda for

Australia, 'with a particular focus on health, water, regulatory reform and the

broader productivity agenda'.[11] As part of its reform agenda, COAG agreed,

on 29 November 2008, to a new framework for Commonwealth-State financial

relations, the terms of which were set out in the Intergovernmental Agreement

on Federal Financial Relations (the 'IGA on Federal Financial Relations').[12]

4.13

The IGA on Federal Financial Relations recognises that 'the primacy of

state and territory responsibility in the delivery of services in these sectors

is implicit in the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia' but also

'that coordinated action is necessary to address many of the economic and

social challenges which confront the Australian community.[13]

4.14

The aim was to:

-

Improve the quality and effectiveness of government services by

reducing Commonwealth prescriptions on service delivery by the States;

-

Provide states with increased flexibility in the way they deliver

services to the Australian people;

-

Provide a clearer specification of roles and responsibilities of

each level of government and an improved focus on accountability for better

outcomes and better service delivery;

-

Rationalise the number of payments to the states for Specific

Purpose Payments (SPPs), reducing the number of such payments from over 90 to

five.[14]

4.15

The IGA on Federal Financial Relations, which commenced on 1 January

2009, consolidated and simplified the forms in which the Commonwealth provides

payments to the states and territories. By it the Commonwealth could deliver

three types of financial support to states and territories:[15]

-

Continued provision of 'general revenue assistance, including the

on-going provision of GST payments, to be used by the states and territories

for any purpose.'[16] It was agreed that the distribution of

payments would continue to be made 'in accordance with the principle of horizontal

fiscal equalisation.'[17]

-

National Specific Purpose Payments (SPPs). The previous

arrangements for over 90 SPPs were replaced with five new national SPPs

corresponding with the five areas COAG identified as 'key service delivery

sectors.'[18]

The Commonwealth agreed to increase the total appropriation for SPPs by $7.1

billion over five years. Each SPP is associated with a National Agreement that

contains the objectives, outcomes, outputs and performance indicators as well

as clarification of roles and responsibilities.[19]

-

A new category of financial support, 'National Partnership'

payments. These are designed 'to support the delivery of specified outputs or

projects, to facilitate reforms or to reward those jurisdictions that deliver

on nationally significant reforms.'[20]

These payments fall into three categories: project payments (to support

national objectives and help fund the delivery of specific projects);

facilitation payments (to help a state lift its standards of service delivery

in areas identified as national priorities); and reward payments (incentives to

encourage states to undertake reforms and attain performance benchmarks). There

has now been agreement to the first wave of these payments.[21]

4.16

COAG agreed that '[a]ll intergovernmental financial transfers other than

for Commonwealth own purpose expenses will be subject to the IGA on Federal

Financial Relations.'[22]

4.17

Ms Mary Ann O'Loughlin, Executive Councillor and Head of Secretariat,

COAG Reform Council, advised that the IGA on Federal Financial Relations is

intended to rationalise the previous measures to address Australia's VFI:

The intergovernmental agreement is a set of significant

reforms of Australia’s federal financial relations. It governs all the policy

and financial relations between the Commonwealth and the states. It set up new

financial arrangements, national agreements and national partnerships between the

Commonwealth, state and territory governments. The national agreements replaced

the more prescriptive tied grant arrangements. The focus of the new agreements

is on agreed outcomes and performance indicators, milestones and benchmarks to

measure progress.[23]

4.18

The Committee was informed that the IGA on Federal Financial Relations

provides for the new funding arrangements to be independently reviewed. The

COAG Reform Council is required to 'monitor, assess and publicly report on the

performance of governments in implementing nationally agreed reforms.'[24] Ms

O'Loughlin advised that:

for the six national agreements...council undertakes a

comparatives analysis of government's performance against the agreed outcomes,

indicators and targets of the national agreements. For reward national

partnerships...the council is the independent assessor of whether the

predetermined milestones and benchmarks have been achieved before the

Commonwealth decides on incentive payments to reward reforms...[25]

4.19

The committee was also advised that the Heads of Treasury Committee is

reviewing the National Agreements, National Partnerships and performance

framework, with particular reference to the availability of data. The Committee

is to report to COAG by the end of 2011.[26]

Federal Financial Relations Act

2009

4.20

The Federal Financial Relations Act 2009 was enacted to implement

the arrangements of the IGA on Federal Financial Relations, including

consolidating in one place the arrangements for Commonwealth payments to states

and territories.[27]

Previous arrangements for the distribution of GST revenue and appropriations

for health, infrastructure and offshore petroleum and greenhouse gas storage to

the states and territories were repealed.[28]

Consistent with its object, the Federal Financial Relations Act made provision

for the calculation and distribution of GST revenue, SPPs and National

Partnership payments. It took effect on 1 April 2009.[29]

4.21

In April 2010, COAG – with the exception of WA – reached agreement on

the establishment of a National Health and Hospitals Network. It was agreed

that:

-

From 1 July 2011, the Commonwealth will fund 60% of the efficient

price of all public hospital services delivered to public patients, 60% of

recurrent expenditure on research and training functions undertaken in public

hospitals, 60% of capital expenditure on a 'user cost of capital' basis where

possible, and (over time) up to 100% of the efficient price of 'primary health

care equivalent' outpatient services provided to the public.

-

The Commonwealth will also fund 100% of primary health care (e.g.

GP services) and aged care (other than in Victoria).

-

The Commonwealth will provide additional $5.4 billion from 1 July

2010 for health reforms and investment

-

From 2011-12 the Commonwealth will dedicate a portion of the

states' (excluding WA) GST revenue to health.[30]

4.22

It was also agreed to make all necessary amendments to the IGA on

Federal Financial Relations and related Commonwealth legislation to reflect the

agreement on the National Health and Hospitals Network.[31]

4.23

The effect of this agreement is that from 1 July 2011, significant

changes will be made to the Commonwealth's distribution of GST revenue and SPPs

amongst the states.

Concerns with the effect of VFI on Australia's federal system

4.24

Evidence to the committee highlights concerns with Australia's VFI. CAF

was critical of the extent of Australia's VFI, arguing that an excessive degree

of VFI is undesirable as it can:

-

weaken government accountability to the public by breaking the

nexus between a government’s decisions on the level of service provision and

the revenue raised to fund it. For every dollar spent by state governments,

less than 60 cents is raised directly for those purposes.

-

reduce transparency regarding who is responsible for which

government services, allowing governments to avoid responsibility by shifting

blame for funding and operational shortfalls to other spheres of government.

Health policy has been a prime example where different spheres of government

responsibility, for funding, operating and regulating across different areas of

the health care system, has resulted in public confusion and opportunity for

blame-shifting.

-

create inefficiencies, including through bureaucratic overlap,

duplication and excess and the cost of administering grants between

governments.

-

misallocate resources, including the inadequate or inappropriate

funding of services.

-

slow the responsiveness of governments to the needs of their

communities.[32]

4.25

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry was similarly critical

of the imbalance between the taxing and spending powers of the Commonwealth and

the states, arguing that several problems arise including:

-

Weakening of accountability: a separation between the two

authorities that raise and spend the revenue (the Commonwealth Government and

the State Government) leads to a weakening of accountability and inefficiencies

in the delivery of state services as State Governments do not bear the political

ill will of raising the taxes to pay for the services.

-

Reliance on inefficient taxes: the States are forced to rely on

inefficient taxes such as stamp duty and payroll tax in order to raise revenue

as their ability to impose more efficient taxes is restricted.

-

Limits incentive for states to cut taxes: the taxes that states

can impose are inefficient and regressive but their reduced revenue raising

capacity gives them very little incentive to reduce taxes.[33]

4.26

This position was echoed by the NSW Business Chamber, which argued that:

Restrictions on the taxing powers of State and Territory

Governments mean that States are unable to take unilateral action to address

this issue. These restrictions on State powers mean that State Governments are

forced to rely on the few taxing powers they have for significant amounts of

revenue, even where it is commonly acknowledged that such taxes are inefficient

and volatile. This can hamper the process of State tax reform.[34]

4.27

For the Government of Western Australia, 'the need for a new federal

fiscal framework is the most important and pressing element of "the reform

of relations" between the Commonwealth and States.'[35]

A similar claim was advanced by the Pearce Division of the Liberal Party of

Australia:

The fact that States lack the capacity to raise the funds

required to fulfil their spending responsibilities is problematic as it reduces

direct government accountability, with State governments not having to make the

difficult choices attached to balancing taxation and expenditure.[36]

4.28

Further to this, it was the Pearce Division's belief that:

Reform of the financial relationship between the Commonwealth

and the States is necessary to strengthen the federation by ensuring that the

States have financial independence and the capacity to independently raise

sufficient revenue to fulfil their constitutional responsibilities.[37]

4.29

It was put to the committee that the current mechanisms to address the

fiscal imbalance do not provide certainty to the states. Professor Galligan

argued that the Commonwealth continues to attempt to control the measures to

address VFI through use of 'accustomed carrots and sticks of intergovernmental

bargaining.'[38]

Referring to the negotiations around national health reforms, the Professor

stated that the Commonwealth had proposed allocating one-third of the GST to

fund the hospitals network; thereby moving away from the current model of

untied grants of GST revenues.[39]

On this point Professor John Uhr commented that the VFI arrangements 'seemed to

be really cutting right into the whole small c Constitution of the GST.'[40]

4.30

Professor Galligan articulated a view that seemed to summarise the

general spread of opinions on VFI given in the evidence to the committee:

Few perhaps prefer the status quo in Australian fiscal

federalism—for federalists it is too centralized,

but for centralists it is too complex and variegated from state to state.

Prospects for change are not promising, however. The Commonwealth was dealt the

superior hand by the constitution, and that superiority was embellished and

legitimated by the High Court.[41]

4.31

Evidence before the committee indicates that the objectives of the IGA

on Federal Financial Relations may not be being fulfilled as well as was hoped.

Several submitters commented that, while the IGA was designed to rationalise

the proliferation of Special Purpose Payments, much of the complexity and

prescriptiveness of the old system appears to be returning via the 'back door'

of increased detail in the new National Agreements and National Partnerships.

The Tasmanian government observed:

It can be argued that only a few of the new NPs and IPs [Implementation

Plans sitting under National Partnership agreements] fully comply with the

new IGA principles. Rather than focusing on outcomes, many agreements remain

focussed on inputs – where and how the money is spent but without much regard

for what is actually achieved. In some cases, the agreements remain highly

prescriptive and continue the practice of Commonwealth micromanagement over

state service delivery.

The new framework has not yet fully realised its ambition of

reducing the administrative burden on Commonwealth and state departments. The

level of oversight and monitoring by the Commonwealth and the reporting

requirements placed on states is increasing costs and diverting resources away

from service delivery.[42]

4.32

Dr Anne Twomey's assessment was more blunt:

[T]he new system of national partnership payments appears to

be a backdoor way for the Commonwealth to interfere again in areas of State

policy through the placement of conditions on payments. As time goes by, it is

likely that specific purpose payments will shrink, national partnership

payments will increase and we will be back to where we started with precisely

the same problems in terms of excessive administration costs, duplication,

waste and blame-shifting.[43]

4.33

The Tasmanian government was also critical of the level of VFI in

Australia, but it did note that it was potentially 'more efficient for a

national government to raise certain revenues...compliance with a national tax

regime can be more efficient for businesses that operate in more than one

jurisdiction.'[44]

Options for reform

4.34

The reform of fiscal federalism is a particularly complex area of

governance, admitting of few easy solutions. The position put by the Business

Council of Australia summarises the situation well:

Ideally, each Government should raise the funds necessary to

fulfil its responsibilities. It is questionable, however, whether Australia’s

revenue raising system could be so radically adjusted given how far the

pendulum has swung in favour of the Commonwealth. Without adjustments, however,

it is likely that the States will become increasingly the service deliverers of

the Commonwealth’s policy agenda.[45]

4.35

At their heart, all negotiations around fiscal reform appear to suffer

from the structural disadvantage by which states and local government are

always placed in an inferior bargaining position. Most options for reform

presented in submissions attempted to address the structural disadvantage

through a clearer reallocation of roles and responsibilities across the

different layers of government as well as providing states and territories with

a greater share of revenue over time to support their functions. Such an

approach assumes that it is actually possible to achieve a list of separate and

distinct roles.

4.36

Whilst there is a growing number of people and organisations calling for

a reallocation of roles between the federal and state and territory governments,

it is less clear that any consensus could be achieved on reallocating those

roles. This is especially so in Australia which has 'a relatively high and

increasing degree of shared functions between different levels of government.'[46]

4.37

Twomey and Withers propose a two-tier method for dealing with

reallocation.

There are two ways of dealing with a reallocation of

functions. The first is the higher level ‘clean lines approach, in which

defined subjects of jurisdiction are allocated to each level of government. For

example, the Commonwealth Government’s National Commission of Audit suggested

that States be responsible for preschool, primary and secondary education, with

Commonwealth funding of secondary education being through untied grants. The

Commission suggested that the Commonwealth take full responsibility for

vocational education and training and higher education.

Not all areas of government are susceptible to ‘clean lines’

divisions. There will always be a need for

areas of shared responsibility. This means

that a second approach needs to be taken to reallocation – not in relation to

responsibilities, but in relation to allocating roles in managing those shared

responsibilities. Better mechanisms for

co-operation are also needed to avoid ‘border issues’, to ensure the

coordination of government services and to avoid cost-shifting.[47]

4.38

In their evidence, Twomey and Withers suggest that this reallocation

could be achieved through constitutional reform, but it was not essential.

Referred legislation could be an option.

4.39

Another model for reallocating roles was suggested in the submission

from the Northern Territory Statehood Steering Committee. It was argued that

the current push by the Statehood Committee for statehood represented a key

opportunity to raise the allocation of roles between the federal government and

the states. The Statehood Committee favours:

[a] process for clarifying the role through concerted policy

action at the Council of Australian Governments level rather than a more

abstract 'grand plan'. The principle that government is accessible and

accountable to those affected by its decisions should have a key role to play

in determining who is responsible for service delivery.[48]

4.40

Not all commentators are as sanguine about the feasibility of

reallocating roles. As seen in chapter one, Professor Galligan believes that

coordinate federalism is an unsophisticated paradigm, one which is

inappropriate for modern Australia. In reality the Commonwealth and the states

or territories inextricably share roles and responsibilities.[49]

4.41

Another option for reforming fiscal federalism, beyond that of

reallocating roles between layers of government, would be to consider more

holistic reform of the tax structure and tax levels. Twomey and Withers argue

that:

[s]erious tax reform would recognise that Australia overtaxes

incomes and undertaxes spending compared to other OECD economies. Our overall

tax take is at the lower end of industrial economies as a share of GDP but is

strongly biased toward income tax sourcing. Both personal income taxes and

corporate income taxes represent higher shares of public revenue in Australia

than in most comparable countries.

Reform could extend further to revisiting horizontal fiscal

equalisation as well as vertical fiscal imbalance and the structure of

taxation. The pursuit of such equalisation in Australia exceeds the pattern in

all other comparable federations. As a consequence, it provides greater

disincentives for sub-national governments to seek and provide efficient

delivery of government services. At a minimum, more transparent and less

complex equalisation processes with improved incentives for efficiency could be

developed.[50]

4.42

Other options for reform of the institutional arrangements include:

-

an expanded Federal Financial Relations Act 2009 subsuming

the existing Commonwealth Grants Commission and acting as a framework 'for

Commonwealth grants of financial assistance to the States, and for the

indexation of those grants' as well as defining the parameters for agreements;[51]

-

a formal tax-sharing agreement between the Commonwealth and

States, based on proportion of Commonwealth tax revenue; and/or

-

states setting their own income taxes (though still collected by

the ATO); and

-

both the Commonwealth and states setting income taxes, to help

boost the proportion of revenue that is gathered directly by the states.[52]

Committee view

4.43

The committee notes that, by comparison with all other federations,

Australia has a high level of VFI. Over time, the VFI has severely undermined

the capacity of the states and territories to raise the revenue necessary to

undertake their assigned constitutional responsibilities. The committee also

notes that over many decades successive federal and states governments have

developed an extensive range of mechanisms to address the problem. These

mechanisms have certainly helped to manage Australia's high level of VFI but

the problem continues to be one of the most controversial in federal-state

relations.

4.44

The committee endorses the recent reforms to Special Purpose Payments,

reducing their total number from more than 90 to just five. However, the

committee notes the strong concerns expressed in evidence for the inquiry that

the new arrangements under the IGA on Federal Financial Relations are not

sufficiently meeting the objectives of reducing Commonwealth prescriptiveness

and increasing state flexibility regarding service delivery. The committee

cautions that the new arrangements must not become a new means for the

Commonwealth to attach overly prescriptive conditions on the payments, and

draws attention to the view of the OECD that measures to address VFI should

avoid complexity and inflexible arrangements.

4.45

While existing mechanisms have improved fiscal arrangements, ultimately,

however, they do not address the underlying fiscal imbalance itself. The

committee notes that as VFI is addressed through Commonwealth grants, states

are largely dependent on Commonwealth actions and policies. The committee notes,

by way of illustration, the Commonwealth's consideration of withholding

portions of the GST to fund national health reforms. This illustrates the

potential uncertainty for the states that can arise where states are to a

significant degree dependent on funding from the first tier of government.

4.46

A number of suggestions were put forward to address fiscal imbalance.

These included reallocating roles between the first and second tier of

Government. The committee considers that without radically reducing the states'

responsibilities, it is unclear that adjusting the role of the Commonwealth and

state governments would, on its own, address imbalances in revenue raising. Other

proposals included holistic reform of taxation structures and levels. The

recently announced review of GST distribution begins to address the issue

around equalisation referred to above. But clearly a broader debate needs to

occur in relation to taxation. The vertical fiscal imbalance in the Australia

federal system needs to be redressed. On the basis of the material presented to

the committee, the committee sees merit in a comprehensive assessment of the

IGA on Federal Financial Relation and taxation levels and structures, to

determine if measures can be taken to provide the states certainty regarding

their revenue raising and their capacity to meeting their responsibilities. As

noted, broader debate is required. The committee considers that the matter

should be referred to the Senate Committee which Recommendation XX of this

report will propose be created. The committee should draw on expert advice, for

example from the Productivity Commission, the COAG Reform Council and the

Commonwealth Grants Commission as required.

Recommendation 9

4.47

The committee recommends that the Joint Standing Committee proposed in

Recommendation 17 of this report inquire into the need for adjustments to the

IGA on Federal Financial Relations and to the level and structure of taxation

in Australia to provide the states certainty regarding revenue raising and

their capacity to meet their responsibilities. In considering this issue, the

committee should inquire into any related matters that the committee determines

are appropriate, including the roles of the state and federal governments, and

seek advice from the Productivity Commission, the COAG Reform Council and the

Commonwealth Grants Commission as required.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page