Part II

Price setting and regulation

Chapter 3

Price setting and key causes of electricity price increases

3.1

This chapter provides a brief summary of how electricity prices are set

and outlines a collection of the wide range of factors contributing to

electricity price rises that have been put to the committee. At the end of the

chapter, the committee draws some conclusions about factors contributing to

electricity prices increases. The following chapter covers some of the more

serious reasons arising from regulatory arrangements in more detail.

Price setting

3.2

There is a mixture of market and regulated price outcomes across the

wholesale, transmission and distribution networks and retail parts of the Australian

electricity sector.

3.3

Wholesale prices paid to electricity generators are a result of the

National Electricity Market (NEM) which provides a highly competitive, computerised

wholesale market on the east coast of Australia. All energy generators go into

a pool and retailers bid. There are five interconnected trading regions that

align closely with state boundaries.[1]

Separate arrangements exist for Western Australia and the Northern Territory

(see Chapter 2).

3.4

There is base pricing and spot pricing. The base pricing tends to

reflect the long run cost of coal based electricity generation under quiet and

stable market conditions. Prices can separate in different regions depending on

demand variations across regions. Temperature fluctuations can lead to

significant surges in peak demand, which can lead to large spikes in the spot

prices which are the settlement prices for the electricity at particular points

in time. Retailers use separate contracts including options and hedging to

manage risks arising from spikes in spot prices.[2]

3.5

The pricing of electricity transmission and distribution network

services is regulated due to the natural monopoly that exists in most cases.

The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) makes determinations on the value of

regulated asset bases and the rate of return allowed, based on the demand and

investment forecasts provided to them by network businesses.[3]

3.6

Demand and investment forecasts for electricity networks are based in

part on reliability standards set by the state regulators. Network assets are

very long-life assets and the consequences of under-building assets can be

catastrophic. Consumers value reliability very highly, but may not wish to pay

for this.

3.7

Some concerns have been raised that current regulatory arrangements have

made it too easy for electricity network owners to over invest and take

increased profits from guaranteed revenue streams.[4]

In contrast, there is a genuine need to replace ageing infrastructure and the

costs of capital required to make the investments have increased since the

global financial crisis.[5]

Further information on what investment has been occurring is available from the

AER and the Energy Networks Association (ENA).[6]

3.8

The relevant state or territory regulator sets price caps in New South

Wales (NSW), Victoria and South Australia and revenue per customer caps in

Queensland, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). Network

service providers (NSPs) recover their price or revenue cap by passing that on

to retailers and thereby onto consumers.

3.9

Electricity retailers must pay both the wholesale price and network

charges for electricity and therefore pass those onto consumers, along with

retail charges and costs as approved by different regulators in states and

territories. Victoria is an exception as it has deregulated its retail

electricity market and prices.[7]

Comparison to other sectors

3.10

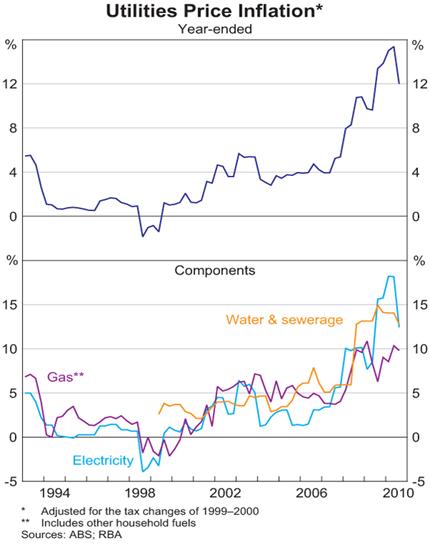

Electricity is not alone: prices have also risen for other utilities as

shown in Figure 3.1. The rise in gas, water and sewerage prices has been

similar to the rise in electricity prices.

Figure 3.1: Utilities price

inflation[8]

Key causes of electricity price increases

3.11

A wide range of possible causes for electricity prices have been raised.

In this section, the committee is mainly focussing on residential prices,

however, business prices are mentioned briefly in relation to the separate

business and retail prices. Professor Ross Garnaut informed the committee that:

In my view, there was no good public policy reason for this

large increase in prices. It happened because of the way we chose to regulate

prices. Contributions to the price increases were made across transmission,

distribution and retail. Generation has not been contributing much to the

increases. Indeed, if you include electricity prices at a wholesale level—that

is, out of the generators, including the carbon price—they are lower in real

terms in October 2012 than in 2006-07. So the huge increases in electricity

prices in Australia over the past half-dozen years are the result of what has

happened in pricing of transmission, distribution and retail margins.[9]

3.12

The contributions to electricity prices vary across different parts of

the electricity supply system, as shown in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Components of an

average Australian household electricity bill in 2012–13[10]

3.13

The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) has estimated that nationally,

residential electricity prices are projected to increase by 37 per cent in

nominal terms. In real terms, this is an increase of 22 per cent. The

contributions to future price increases across components of the electricity

industry are estimated to be:[11]

|

Transmission

|

6.0 per cent

|

|

Distribution

|

33.6 per cent

|

|

Wholesale

|

40.2 per cent

|

|

Retail

|

12.1 per cent

|

|

Carbon Tax

|

5.7 per cent

|

|

Feed-in tariff

|

2.8 per cent

|

|

Large-scale Renewable Energy Target (LRET)[12]

|

3.8 per cent

|

|

Small-sale Renewable Energy Scheme (SRES)[13]

|

-0.8 per cent

|

|

Other state based schemes

|

2.3 per cent

|

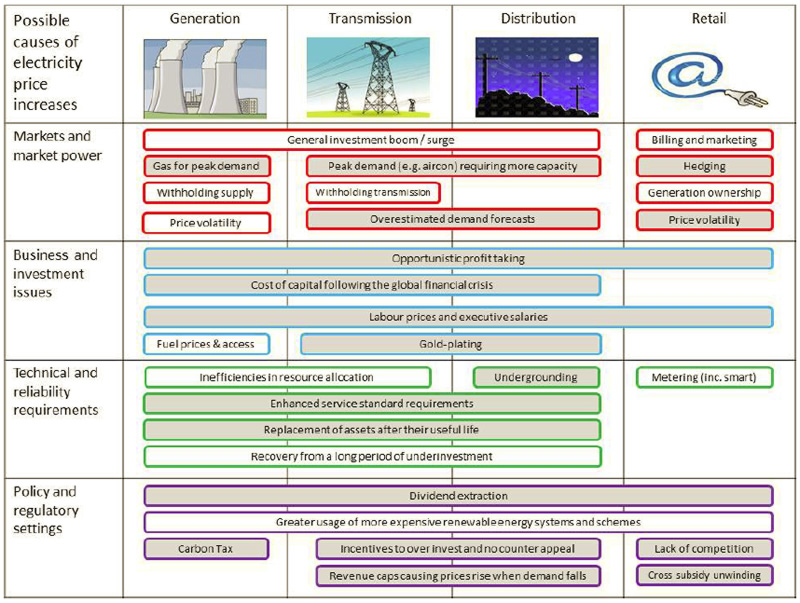

3.14

In addition to their own usage levels, the electricity price increases

incurred by consumers are also influenced by factors including electricity

markets and market power, business and investment issues, technical and

reliability requirements, and policy and regulatory settings. The discussion in

the rest of this chapter covers some of the possible causes of electricity

price rises that have been raised with the committee and are grouped in Figure

3.3.

Figure 3.3: Possible contribution

to electricity prices

Markets

and market power

3.15

The committee was informed of a range of market and market power factors

that may contribute to electricity prices, including demand, demand forecasts,

an investment surge, changes in peak demand, wholesale prices, lack of retail

competition, cross-ownership, hedging, billing and marketing. The following

sections briefly summarise each of those potential contributions to electricity

prices across the generation, transmission, distribution and retail components

of the electricity industry.

3.16

Where there is sustained abuse of market power, the regulator has some

powers to step in, in some circumstances, but generally the regulator must act

by taking the relevant companies to court.[14]

Investment surge

3.17

The surge in investment in the electricity industry is coinciding with

the well-known surge in business investment across the economy more generally.

Similarly in the late 1970s and early 1980s the surge in investment in the

electricity industry coincided with the more general surge in investment that

also occurred at that time.[15]

Professor Stuart White elaborated:

This has been a big issue in network assets. We tend to have

cycles of significant network investment and then cycles where we see less.[16]

Demand and demand forecasts

3.18

The National Generators Forum (NGF) informed the committee that in

recent years overall demand for electricity has been falling:

[O]ver the past five years, electricity demand across the

national electricity market has been declining. It has declined by around 3½

per cent over that time frame. That is due to a range of reasons—notably, the

increase in the retail price of electricity; declining industrial demand;

reduced manufacturing activity; energy efficiency initiatives; and solar PV

systems.[17]

3.19

Noting that demand forecasts are central to price and revenue caps in

the regulated parts of the industry, concerns have been raised about the

regulatory decisions that have been based on forecasts of rising demand, given

that demand is actually falling. The AER noted its approach to considering

demand forecasts provided by electricity businesses:

We do receive demand forecasts from the business. We

challenge those. I think it would be unusual for us to accept the demand

forecasts that have been put in front of us, and there have been a range of

reasons for that. So that power currently exists, and we would continue to examine

those demand forecasts and also to look to external advice for confirmation of

an appropriate demand forecast.[18]

3.20

The AER also pointed out the forecasts for peak and aggregate demand

have different impacts of electricity prices:

We probably ought to recognise that there are two categories

of demand forecast, and it is important to recognise the distinction. One is

peak demand, and it is peak demand that drives investment. The other is

aggregate demand, and aggregate demand is important for recovering costs,

because you recover over the total demand, and that determines prices.[19]

3.21

Energex explained to the committee how the falling demand in recent

years had impacted electricity prices.

More recently, deteriorating network utilisation as total

energy consumption has moderated is forcing up network prices as the costs of

providing, operating and maintaining the network are spread over a lower

consumption base whilst maximum demand remains at record levels.[20]

Peak demand

3.22

The committee noted information suggesting that peak demand has

increased due to a greater deployment and use of air conditioners and other

appliances in recent years requiring more transmission and distribution

capacity that is only used a small fraction of the time.[21]

The Productivity Commission noted that 'some 25 per cent of retail electricity

bills are required to meet around 40 hours of critical peak

demand each year'.[22]

The problems of peak demand were echoed by the Alternative Technology

Association (ATA):

The current state of rising electricity prices is primarily

driven by a failure to manage peak demand, both at a network and a generation

level. The inability or reluctance to properly engage the demand side of the

market has led to over investment in and inefficient operation of the electricity

system as a whole.[23]

3.23

Other submitters and witnesses stated '[p]eak demand is a real issue'[24]

and:

Our key messages are that network costs and costs of peak

demand are the single biggest drivers of rising electricity prices—we recognise

that—and that energy consumers, from our point of view, and business consumers

want reform.[25]

[Another] driver is the cost of supplying power for what we

call peak demand, which is those five to 10 days a year. On the mainland of

Australia they are the hot days; the summer peaks are the clear peaks. Around

20 to 25 per cent of the generation and transmission infrastructure is designed

to supply power for those peak days. Bringing those peaks down is a critical

opportunity to reduce the cost of energy to households and businesses in

Australia.[26]

Peak demand has surged in recent times with the dramatic

growth in air conditioning load driving network companies to invest for the

short summer peak...[27]

3.24

While investment in networks to support peak demand is a glaring issue,

the committee was informed that some care is needed in assessing the impact of

both generation and network investment as indicated by Grid Australia:

It is possible you could increase generation capacity by 25

per cent and have no transmission increase if that generation is located at

points where there is spare capacity in the network. If somebody wants to make

a development and pay for a development that is, for example, remote or where

there is limited capacity and you need to increase it, then that may drive

costs. It really depends on where the generation connects and what sort of

capacity there is at any point in the network. It is quite a complex answer.[28]

3.25

Another impact of peak demand is the need for generation systems that

can switch on quickly and be available to meet rapidly rising demand on a given

day, however a downside is that those systems may then be idle and not directly

earning a return for significant periods:

While difficult to quantify with precision, the increase in

peak to average demand between 1997 and 2010 is estimated to have required an

additional 6 300 MW of (peak) generation capacity, compared with what would

otherwise have been the case...The additional peaking capacity represents around

13 per cent of current generation capacity, and while it is critical in terms

of meeting peak summer demand during extremely hot periods, it sits idle for

the majority of the year. (It represents an investment of around $6.2 billion,

which is around 6 per cent of total capital investment in Electricity supply

over the period.) [29]

3.26

The committee also heard a different point of view, suggesting that peak

demand is not increasing and that demand forecasts predicting an increase are

inaccurate.[30]

Data from the AER indicates that over the last four years (that is, since

2008–09) the level of peak demand is flat or falling for bother summer and

winter in states serviced by the NEM.[31]

Wholesale prices

3.27

Changes in wholesale prices were raised with the committee on a number

of occasions. Much of the evidence presented to the committee suggested there

had been some downward pressure on wholesale prices, as the following example

indicates.

[W]holesale electricity prices in the national electricity

market over the past 14 years. It shows the nominal electricity price. What you

can see is that the price has remained almost constant over that period of

time. There was a period during 2008 when, principally due to the drought and

the hot weather conditions, the prices increased. But, generally speaking,

prices have been very flat and stable. Today the prices are around 50 per cent

lower than what they were in the mid to late 1990s when electricity generation

was owned and operated by state governments. I should say that that excludes

the impact of the carbon price.[32]

3.28

It has been suggested that some electricity generators may be able to withhold

electricity supply capacity in order to have a material impact on price.[33]

Professor Alan Pears AM cited some other information:

There has been evidence over many years that some generators

have "gamed" the system by limiting generation capacity at times, to

push up prices. ABARE (2002), drew attention to this and estimated the cost to

the economy of this practice at between $81 and $412 million per annum. Recently

media reports have raised more alleged examples...The structure of the market, in

which all bidders on the spot market are paid the price bid by the highest

successful bidder, creates an incentive to "game".[34]

3.29

This issue has created sufficient concern among some stakeholders that a

formal rule change through the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) has

been sought by the Major Energy Users Inc (MEU). The rule change request seeks

to constrain the perceived exercise of market power by generators in the NEM.

The MEU's concerns included:

The MEU considers that during periods of high demand when the

system is operating normally, some large generators do not face effective

competition and have the ability and incentive to use market power to increase

the wholesale electricity spot price.[35]

3.30

In its draft determination, the AEMC concluded that:

Based on the AEMC's analysis, consultant analysis and

stakeholder feedback to the consultation paper, directions paper, public forum

and technical paper, there is insufficient evidence of the existence of

substantial market power to warrant the introduction of a rule that restricts

the dispatch offers of generators in the National Electricity Market.[36]

3.31

Similarly, it has also been noted that it may be possible for owners of

transmission rights to withhold transmission rights from the market,

effectively reducing the capacity of the congested interface.[37]

Retail – billing and marketing

3.32

Concerns about the lack of competition in the retail component were also

raised as a contributor to electricity prices:

In the case of retail, the problem is inadequate competition,

and the remedies are the standard competition policy remedies. So I think we

have the types of mechanisms that can deal with issues there.[38]

3.33

Retailer's indicated that in their view they have often received a large

share of the blame for price increases even though they only contribute a small

fraction of the price rise:

As retailers are the billing agent for the entire electricity

industry value chain, we bear much of the consumer backlash over rising

electricity prices while the retail component of the price rises has been very

low.

While retailers have not driven the price rises, we have to

deal with the customer backlash and with the increased customer payment

difficulties they cause while carrying the credit risk for the entire industry

as we must meet our payments to the market generators and networks. Retailers

also believe they have been targeted by the political and regulatory bodies in

response to rising prices even though we have not caused them.[39]

3.34

The committee also noted that changes to billing, marketing and metering

systems have contributed to retail prices increases in NSW of around one per

cent from July 2012.[40]

The committee heard that structural issues may remain for retail competition in

the electricity sector:

But certainly a very large part of the price increases has

really been market failure in a whole lot of areas, in the way retail

competition is structured, in the way networks are regulated—and that is the

work ahead of us. It is not necessarily just keeping prices down, but it is

getting prices to work in an effective, efficient and equitable way.[41]

Retail – generation cross-ownership

and hedging

3.35

The level of cross-ownership between retailers and generators in the

industry has been raised as a potential conflict of interest that may drive

price increases. The ATA informed the committee that:

[I]f we are talking about why the lower wholesale prices have

not been passed through to the retail level, that is because of hedge contracts

that exist—and they are projected out for two or three years, potentially

more—between retailers and generators, often retailers that own their own

generation, and so it takes some time, as we have seen up until yesterday, with

the regulator's decision, for the reduction in the spot market price to flow

through to retail bills, but that does happen.

[42]

3.36

The Energy Retailers Association of Australia (ERAA) responded to the

concerns about cross ownership, stating:

In no state is cross-ownership at such a level that the ACCC

has indicated any concerns about market concentration to date. It comes down to

those risks. When you have a wholesale electricity market that varies in price

anywhere from a negative price to $12,500 a megawatt hour in half-hour

increments, it is a highly risky business. When you have a large retail

customer base where your opportunity to vary your retail prices in line with

movements in the wholesale price is very restricted by price regulation, then obviously

one of the things you do as a natural hedge management strategy, a risk

management strategy, is to have your own forms of generation in case they are

required in peak periods.[43]

Wholesale market prices change in half-hour increments and

can vary in price anywhere from zero, or even a negative price, to $12½

thousand a megawatt hour. Retailers must sell at regulated or their notified

prices so it is retailers, not consumers, who bear the risk in a volatile

wholesale market.[44]

3.37

The ATA also noted that volatility in market prices can drive very

expensive hedging contracts, which ultimately impact the costs of electricity

to consumers:

[O]ne reason is simply the price volatility in the market.

The National Electricity Market has an enormously high cap, $13,000 a megawatt

hour during peak times, and there is significant price volatility, particularly

during peak times, which is driven by our failure to manage that peak. That

leads, by any normal economic theory, to significant amounts of hedging and

costly hedging, because the retailers have to manage their risk in terms of

whether they have to dip into that spot market and pay those high prices.[45]

3.38

The committee heard that the volatility in price can be specific to

particular regions. The AEMC noted South Australia is an example of such

localised volatility in prices:

One of the characteristics of the South Australian wholesale

market is that although average prices have tended to converge, South

Australian prices tend to be more volatile than those in other jurisdictions.

In fact, we have had an average over a week where at one stage the wholesale

price was negative. That volatility is a risk factor which when you are

contracting at the wholesale level tends to increase the costs of

contracting—there is a risk margin in order to manage that volatility.[46]

Business issues

3.39

The committee was informed of a range of business issues and factors

that may contribute to rises in electricity prices, including profit taking,

cost of capital, labour costs, commodity prices and other supply issues. The

following sections briefly summarise each of those potential contributions to

electricity prices across the generation, transmission, distribution and retail

components of the electricity industry. Investment issues are discussed in the

later section on gold-plating.

Profit taking

3.40

Many factors across the electricity industry have been noted as possible

causes of price increases but there is one reason that really stands out to

households: profit taking. The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) dataset

8155 on industry performance indicates that operating profit before tax in the

electricity industry increased from $5.4 billion in 2007–08 to $9 billion

in 2010–11, an increase of 67%.[47]

In the same time period electricity prices rose by over 40%.[48]

3.41

Whether those increased profits are coincidental or opportunistic profit

taking is hard to determine. Mr Nino Ficca of SP AusNet responded to questions

about profit taking, stating that:

Our profitability has been fairly consistent. Investors in

network businesses do not look for disproportionate profits, they look for very

predictable and very stable outcomes. I do not think there has been any

disproportionate profitability—in our sector anyway. It is very much steady and

long-term predictable outcomes. On the cost side, our cost of equity has gone

up substantially post-GFC. Equity markets are very tough at the moment, debt

markets are very tough at the moment and we need to maintain our obligations

both to safety and to reliability from our networks perspective. There has been

that tension. I can say for our business, our profit was flat last year. We had

no increase—I think it was 0.8 per cent over the last year. I do not know, as a

private sector business, that our profits have been growing at anything other

than what you would expect in a normal sense.[49]

Cost of capital

3.42

The cost of capital has increased significantly following the global

financial crisis. The AER has approved an increase in allowed returns on

investment capital of around 1.9 per cent from 2004–05 to 2008–09. The

committee noted that each one per cent increase has been estimated to imply an

additional $780 million in interest payments that are passed on to consumers.[50]

Ergon and Energex described their experiences regarding the cost of capital:

When you look at all our modelling, the major influence on

costs and price at the end of the day is cost of capital. Because our

determination was in 2010 and we came off the back of the global financial

crisis, the cost of debt was significantly higher.[51]

The price that is charged as part of the network charge is

effectively a building block charge, which includes cost of capital, a return

of capital depreciation and operating costs. So a large portion of the charge

is in fact reflective of the cost of capital. That is reset every five years.

When you are in a situation, as we both were in the middle of the GFC,

resetting your regulatory determination and your weighted average cost of

capital, that is where you saw an increase in that cost which flowed through

the network prices at that time.[52]

Labour costs

3.43

While labour inputs to the electricity sector had been relatively flat

between 1996 and 2006, from 2007 onwards they have risen sharply[53]

due to an increase in the size of the electricity supply industry workforce:

since a low of 35 000 employed persons in the November quarter of 2006, the

electricity supply industry workforce has increased to 71 900 employed persons

in the August quarter of 2012.[54]

From its examination of the productivity of electricity and other utilities,

the Productivity Commission reported that:

The rise in labour inputs is confirmed by examination of

company annual reports, particularly those of the major electricity

distribution companies that collectively account for the majority of labour

inputs in the sector. Labour inputs have been increased to upgrade and augment

network infrastructure, to assist distribution businesses respond to ageing

workforces, and to prepare for skills transfer as older workers retire.[55]

Commodity and other input prices

3.44

As many coal-fired power stations have co-located coal mines, the input

price of coal has not necessarily been greatly affected by the unusually high

export coal and other commodity prices that have occurred in recent years,

although some of that commodity price impact is flowing through to consumers.[56]

The committee was informed about the impact of gas prices to date and potential

future impacts:

[W]e have seen significant changes in gas prices in Western

Australia over the last few years, particularly as we have seen gas and coal

prices being determined in a global market. We also see domestic gas demand

rising without necessarily a corresponding rise in supply—hence the cost or

price pressures that were involved in that environment. There is also a lack of

competition in the domestic gas market with the supply side being dominated by

two major suppliers and demand is concentrated effectively in five key

consumers of gas.[57]

[A]lthough gas prices are rising, there is still a lot of

uncertainty as to where they will be in the medium to long term. If you build a

gas fired power station you are looking to operate it for the next 30 to 40

years, but if you cannot take a view on what your fuel cost is going to be then

you cannot work out whether you are going to be competitive in the marketplace.[58]

3.45

The committee also heard how weather conditions had affected particular

types of generation, such as hydro and wind power, during particular periods:

South Australia, for instance, does not have a lot of good

quality coal; it is reliant on gas and, more recently, has had a very high

penetration of wind. In Tasmania there was a period,

particularly during the drought, where energy out of their hydro system had to

be carefully managed.[59]

Technical and reliability

requirements

3.46

The committee was informed of a range of technical and reliability

factors that may have contributed to recent increases in electricity prices,

including service and reliability standards, asset replacement after its

useful life (including catch-up on previous under investment), underground

cabling and metering systems. The following sections briefly summarise each of

those potential contributions to electricity prices across the generation,

transmission, distribution and retail components of the electricity industry.

Service and reliability standards

3.47

Some state governments, including those in NSW and Queensland, have in

recent years increased the standards to which they require networks to operate.

While this improves the reliability of supply, this has also added to the

costs. The Ai Group informed the committee that in its view:

Some elements of the network-related price increase are

related to policy—for instance, policy decisions to have particular reliability

standards. Whether those are good choices or bad choices, there is scope to

improve how the system operates on that front.[60]

3.48

Energex told the committee a review of security and reliability had been

a significant driver in electricity prices in Queensland:

For Energex, the key factors are the improvements in security

and reliability in response to the first Somerville review in 2004 in

Queensland, and also the cost of capital established at our recent reset, which

was in the midst of the GFC, and the demand forecasts at the same time.[61]

3.49

The committee noted that enhanced service standards and reliability

requirements in NSW have contributed to around nine per cent of the approved

capital investment.[62]

The AER reported that, in its view, the reliability settings were above levels

that consumers would value:

[T]he reliability settings for the distribution in New South

Wales have been set above the levels that consumers would value. That has been

the view of AEMC and they have recently come out with a report suggesting that

consumers may find better value with some relaxation of those standards, and

those matters would now be considered by government. They would then feed into

our next round of determinations.[63]

Asset replacement after useful life

3.50

Replacement of assets after their useful life has also been suggested as

a significant contributor to electricity prices. The Productivity Commission

analysed the capital investment in electricity infrastructure and demonstrated

a surge in recent years, as shown in Figure 3.4 below. The Productivity

Commission noted that:

Electricity supply is characterised by periodic surges and

declines in the rate of growth of generation and network capacity. The strong

growth in capital and labour inputs in [electricity supply] from the late 1990s

to 2009–10 is the most recent of a number of investment surges in [electricity

supply] that have occurred over time. It is consistent with the observation

that much of the growth in capital and labour inputs during the period has been

associated with a major program of infrastructure renewal or replacement.

Infrastructure assets built in the mid-to-late 1960s that had

a lifespan of 30 to 40 years would likely have been up for replacement or

refurbishment from the mid-to-late 1990s onwards. Similarly many of the assets

built in the investment boom of the late 1970s early 1980s would also have been

at or near retirement or renewal age from the early 2000s onwards.

Refurbishment and replacement of these assets would also be contributing to the

surge in investment since the late 1990s, and particularly in the past five

years or so.[64]

Figure 3.4: Electricity supply:

Real capital investment ($ million), 1961–62 to 2009–10, constant 2006–07

dollars[65]

3.51

Such asset replacement of electricity networks is estimated to account

for around 31 per cent of the $14 billion of approved capital expenditure in

NSW, which is particularly significant given that networks costs contribute 51

per cent of the overall cost of electricity.[66]

The committee noted that:

The investment needed in the NEM is forecast to exceed $7

billion for transmission and $35 billion for distribution over the current

regulatory periods. This is a rise in investment from the previous periods of

82 per cent and 62 per cent (in real terms) in transmission and

distribution networks respectively.[67]

3.52

During the 1990s there was a significant under-investment in electricity

infrastructure and some of the investment now being undertaken is to

"catch up" on what should have been done then.[68]

In spite of that, inefficiencies in resource allocation are still occurring.[69]

Underground cabling

3.53

The committee noted the impact of an increased usage of underground

cabling, versus poles and wires and the cost impact arising from that. The

overall quantity of underground electricity cabling in place remains small (around

13 per cent) relative to overhead cabling. However, in the most

recent decade around 60 per cent of installed electricity cabling has been put

underground, compared to 20 to 25 per cent in the two previous

decades. Given that the cost ratio of underground to overhead cabling can range

from 2:1 at 11kV to 20:1 or more at 400kV, the greater deployment of underground

power lines can significantly contribute to network costs.[70]

Changes to metering systems

3.54

Changes to billing, marketing and metering systems have contributed to

retail price increases in NSW of around 1 per cent from July 2012.[71]

The Consumer Action Law Centre (CALC) noted that the installation of new "smarter"

technologies in Victoria, designed to better manage energy systems, was also

potentially contributing to electricity price increases.[72]

Policy and regulatory factors

3.55

A range of policy and regulatory factors may have contributed to recent

electricity prices increases, including unwinding of cross subsidies, weakness

in the existing rules, problems with the merits review process, financial flows

out of the sector, such as increased dividend from government owned entities,

renewable energy programs, the carbon price and issues with revenue and price

caps. The following sections briefly summarise each of those potential

contributions to electricity prices across the generation, transmission,

distribution and retail components of the electricity industry.

Unwinding of cross subsidies

3.56

As shown in Figure 3.5 below, average Australian household electricity

prices were relatively constant in real terms between 1991 and 2007. From 2008

onwards, household electricity prices have risen rapidly, with an average

national rise of around 40 per cent in real terms over the last three years.

While the price of business electricity has also risen in recent times, it is

now similar to 1991 business electricity prices in real terms due to

significant decreases in business electricity prices in real

terms during the 1990s:[73]

While there is some variation in the extent of price rises

across the states and territories, they display a consistent upward trend in

prices over this period. These increases have been well ahead of the general

increase in prices and faster than growth in average wages. While the

consumption of electricity makes up a relatively small component of a typical

household's expenditure, these price rises are putting pressure on lower income

households.[74]

3.57

The AER noted 'that upward trends in real household electricity and gas

prices over the past decade in part reflect the unwinding of historical

cross-subsidies from business to household customers that was necessary as

jurisdictions phased in retail contestability.'[75]

Figure 3.5: Average electricity and

gas real index for Australian capital cities[76]

Weaknesses in existing rules

3.58

The committee heard a lot of evidence about the contribution of existing

regulatory arrangements to electricity price increases. This section will

briefly cover some of the impact on cost, while the following chapter will

cover regulatory issues in more detail. The AER informed the committee that the

existing regulations have led to price increases beyond what has been necessary

for a safe and reliable supply:

There have been a range of reasons for recent price

increases—rising generation costs, rising retail costs and the costs of meeting

green schemes have all played a part. But the rising costs of the electricity

network have been the main contributor to price increases in all states. There

are a range of factors driving these increased network costs. The need to

replace ageing equipment and meter peak demand has driven significant network

investment across the market. However, our submission emphasises that, while

much of this investment was necessary, weaknesses in the regulatory

framework—that is, the rules that set out how the AER must regulate prices—have

led to price increases beyond what has been necessary for a safe and reliable

supply.[77]

3.59

The AEMC also noted concerns about the existing rules:

The price and reliability outcomes in this regulated network

sector, in our view, are a function of three things: (1) yes, the rules; (2)

the way the rules are interpreted and applied, including through the merits

review process; and (3) the corporate governance of the businesses involved.[78]

3.60

The committee noted the importance of stability for business to be able

to operate, but was also interested to hear the following view on difficulties

arising from the five year terms of the regulatory determinations:

I think five-yearly price controls setting prices or revenues

for five years and fixing them for that period of time are a very onerous form

of contract. I think that it requires discipline on the part of shareholders

and managers to be able to operate effectively under that, and I think the

conflict-of-interest and other governance issues that are linked to government

ownership of the networks simply have demonstrated quite clearly—the data seems

to suggest—that it has not actually achieved suitable outcomes.[79]

3.61

The committee was told about a particular issue that has arisen in South

Australia, in which South Australians are bearing the costs of cheaper power

for Victorians, noting the proposed rule change to address this issue:

The effect of a generator connecting to the network on how

the rest of the network operates and the capital expenditure required is really

where the major part of the expense is. Under the current rules it is true that

that expenditure on the network is allocated to consumers in South Australia.

Even though the power may be being consumed by Victorians,

the network costs to generate that power are being incurred by South

Australians.

We have a rule change we are dealing with at the moment that

deals with the interregional aspects of the problem, so that if energy is being

consumed by Victorians, even though the transmission kit might be in South

Australia, Victorians will pay for that transmission kit—likewise for New South

Wales and Queensland.[80]

Revenue and price caps

3.62

The committee heard how revenue caps can cause prices to rise when

demand falls. The arrangements with revenue caps were set up some years ago,

when there was consistent growth in demand. However, given that revenue is a

product of price and demand, fixed revenue caps may cause price rises as demand

has fallen in recent times, as explained by the Total Environment Centre (TEC):

Where peak and/or total demand are flat or falling, under a

revenue cap, network revenue remains constant, so networks have an incentive to

encourage more energy saving measures, as any further decreases in costs result

in increases in profits. The downside for consumers is that if demand proves to

be lower than forecast for much of the 5 year determination period, the

networks get a windfall profit, since their revenue was determined by the

original forecast.[81]

3.63

Professor Garnaut held a similar view, stating that:

[I]f demand falls price is increased to make sure that

companies get their guaranteed rate of return. So, as demand has fallen, prices

have had to be increased even more than they otherwise would have been. Of

course, if price then goes up in response to demand falls, then demand falls

even more.[82]

3.64

The Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE) responded

to questions on the relationship between demand reduction and electricity

prices, noting that they had work underway to better understand what was

occurring:

The modelling exercise is currently underway. We do not yet

have any final results from that exercise but the modelling is well and truly

underway. We would expect there would be results to hand over the coming weeks.

There is an expectation that there will be public consultation on the basis of

those results and an accompanying regulatory impact analysis of the proposal

for a national Energy Savings Initiative.[83]

3.65

The committee was also informed about problems with price caps, such as

a potential incentive or opportunity for networks to "game" the

market:

Under a price cap the AER divides revenue requirements each

year by the projected units of sales to determine a price. A price cap requires

a 5 year forecast of demand. The price is set on an annual basis; but unlike a

revenue cap, once it is set it cannot be compensated for the following year, so

the networks get to either keep the profit they have made when demand is higher

than anticipated, or are forced to bear the losses when the reverse occurs. A

price cap therefore provides networks with a significant opportunity to game

the market.[84]

There is a lack of market signals out there. If the Reserve

Bank sees the market heating up, they change interest rates; electricity prices

do not.[85]

Merits review process

3.66

Under current arrangements, the AER's revenue and price setting

decisions are subject to merits review in the Australia Competition Tribunal

and this option is frequently used by network operators to achieve higher prices

and revenue caps.[86]

Part of this is perceived by some to be associated with the merits review

process being too easy and the automatic additions of assets to the regulated

assets base.[87]

The AER quantified the extent of this problem in dollar terms:

Our submission also highlighted the impact of appeals of AER

decisions on electricity prices. The outcomes of these

appeals, heard by the Australian Competition Tribunal, have increased revenues

to network businesses by some $3 billion out of some $58 billion over the

current five-year obligatory period. A review of that appeals mechanism is

currently underway.[88]

3.67

Evidence presented to the committee indicated that in NSW, the capital

expenditure overspend (the IPART/Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

(ACCC) approved expenditure) has grown from a few $10s of million 2004–05 to

almost $600 million in 2008–09. The Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism

(DRET) went on to note that:

...an overspend does not imply this additional expenditure is

inefficient. Capex overspends may be an efficient response to a range of

legitimate drivers; for example, as a result of changes to reliability

standards and demand outcomes being different to what was forecast. However, it

is essential that consumers have confidence that the regulatory framework does

not incentivise unnecessary investment.

The ability of the AER to test the efficiency of overspends

is a matter currently being reviewed as part of the AEMC’s Economic Regulation

of Network Service Providers rule change process.

The AEMC’s draft rule provides for new tools under the National

Electricity Rules (NER), such as capital expenditure sharing schemes and

efficiency reviews of past capital expenditure so the AER can incentivise

network service providers to invest capital efficiently. [89]

3.68

Professor Garnaut drew the committee's attention to the lack of

opportunity for counter appeal by the regulator and suggested that allowing

counter appeals by the regulator may contribute to keeping prices down:

[T]he rate of return is set by the regulator. It can be

appealed by players in the industry and there is no opportunity for counter

appeal by the regulator. So removing that unusual imbalance, in which those who

want higher prices can appeal the regulated outcomes but there cannot be a

general counter appeal by the regulator, would make a contribution. If that

were removed it might simply be a matter of the regulator applying, more

rigorously, commercial and economic principles, because there is no doubt that

the rate of return has been set substantially in excess of the supply price of

investment to this industry. The test of that is that anyone who happens to own

a regulated asset would not be prepared to sell that asset for an amount of

money equal to the regulated asset base. They would want a premium, which shows

that the rate of return that is being allowed on the investment is higher than

the supply price of investment.[90]

3.69

The department informed the committee that the AER and SCER are

examining whether the merits review process can be improved.[91]

Financial flows to

state-governments

3.70

The Prime Minister noted that some state and territory governments have

been profiting from price increases under current regulatory arrangements:

[I]n many places around Australia, the State Governments both

own lucrative electricity assets and regulate parts of the electricity market.

The comparison between the private and public owned utilities

shows the States are doing very well financially out of this arrangement.

Following the recent round of price increases, revenue for

network enterprises wholly owned by State Governments is up fifty per cent over

the previous five year period.

In other words, revenue to the states went up nearly twice as

fast as revenue to the private network operators.[92]

3.71

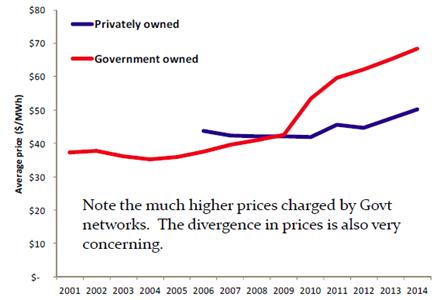

A presentation recently delivered by the Energy Users Association of

Australia (EUAA) Executive Director highlighted the discrepancies in

distribution prices between private and government owned entities as shown in

Figure 3.6.

Figure 3.6: Distribution prices[93]

3.72

DRET noted, however, that the characteristics of the market vary in each

state and territory and this could influence any cost comparison analysis. For

example, cost comparisons between state and privately owned utilities may not

take into account the length of the NEM in each jurisdiction and other

differing attributes.

3.73

The NSW government budget papers provided an overview of the dividends

and corporate tax revenue it receives from its utilities. The tables below

provide a breakdown of these sources of revenue. They indicate the NSW

government will receive $999 million in dividends from electricity generation

and distribution and transmission and an additional $546 million from Snowy

Hydro in 2012–13. There is a decrease in dividends from electricity generation

from the previous year of $83 million and an increase in distribution and

transmission dividends of $262 million. Both categories of energy

dividends then decrease over subsequent years.[94]

Figure 3.7: NSW government

Dividends and Income Tax Equivalent Revenue[95]

Figure 3.8: NSW government 'Other

dividends and distributions' (Snowy Hydro Limited)[96]

3.74

The NSW Treasurer, the Hon Mike Baird MP, has outlined that the revenue

from the electricity dividends is reinvested in the community to fund schools, hospitals,

transport and police.[97]

3.75

Chapter 8 of the Queensland government budget strategy papers provided

an overview of its 'public non-financial corporations sector'. It indicated the

Queensland government will receive $727 million in dividends in 2012–13 from

the energy sector.

Figure 3.9: Queensland government ordinary

dividends[98]

3.76

Professor Garnaut noted that it was essentially a policy question for

the relevant state government and they could choose to lower electricity

prices:

The question is different in publicly owned and privately

owned networks. Where they are publicly owned—and this is

overwhelmingly the case in New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia and I

think Tasmania—the issue does not involve any effect on the wealth of private

firms. Here it is a straightforward public policy question. Really the question

is: is artificially raising the price of electricity a good way for these

governments to raise revenue? I would suggest that it is generally not a good

way, and it is within the power of the governments themselves to apply a lower

rate of return and bring down electricity prices. That will have an effect on

government revenue. I would expect that there will be alternative forms of

revenue that could give you the fiscal effect you want at much lower cost to

the community.[99]

Renewable energy

3.77

Greater usage of more expensive renewable energy systems and Renewable

Energy Targets (RET) have also been suggested to contribute to both price

increases as well as price decreases, as explained by the REC Agents

Associations:

The renewable energy target, which is a national scheme, has

come in for a bit of criticism from some quarters and is blamed for a large

part of the increase in retail electricity prices. While it is clear that the

renewable scheme has contributed to rising power prices, it is currently less

than 1c per kilowatt hour, which is roughly equivalent to 3.4 per cent of

retail prices, and a similar amount is due to state based schemes. Importantly

though, the cost of the national renewable scheme is expected to reduce. That

is the direct pass through of cost; however, the implementation of solar

systems has led to a reduction in electricity demand and we have seen wholesale

prices fall quite a lot over the last few years. That is because there has been

more competition from generators to meet a lower demand. So renewable energy is

actually contributing to lower wholesale prices.[100]

3.78

Professor Stuart White from the Institute for Sustainable Futures at the

University of Technology Sydney (UTS) also noted that were there any cost

increases, these were small compared to network costs:

One is the impact of environmental requirements, of which the

mandatory renewable energy target is one. ... that is a factor in the increase in

prices, and of course many state based schemes have increased the price. But it

is small relative to the network spin. So the second factor you mentioned,

about increasing the value of assets and so on, is probably a much larger one.

The spending on networks is $45 billion—an awful lot of money, and that swamps

the impact of such measures as the mandatory renewable target, the feed-in

tariffs and so on, many of which are being phased out in any case.[101]

3.79

In addition, the Ai Group suggested the RET can put downward pressure on

prices, in both the small and large scale schemes:

But there are some countervailing effects from the two

components of the RET. So the extra generation that the LRET brings on has to

some extent—and there is some controversy over the size—a depressing effect on

wholesale electricity prices. Some observers think that that is strongest in

South Australia, where most of the wind capacity is, and less significant

elsewhere. The small-scale scheme, where most of the activity has been over the

last couple of years, may be playing a role there as well—although that is even

more complicated to assess.[102]

3.80

Professor Garnaut also noted the downward pressure on price from the RET

and noted that it may contribute to lowering the carbon price:

The steady expansion of renewable energy supplies under the

RET is forcing down wholesale prices, and it is possible, although not certain,

that in the middle of 2015 with the linkage to the European market we would

have a lower carbon price than we do today.[103]

3.81

The committee was also informed of the complexity and variables involved

in forecasting Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) prices and that the current

RET review may provide some helpful analysis:

In forecasting REC prices, though, there are an enormous

number of variables around demand and the wholesale electricity market factors

relating to local planning requirements for building specific projects, the

costs of individual renewable technologies. There are a whole range of factors

that come into play in forecasting future REC prices that make it extremely

difficult. I should say that the RET review that is currently underway would have

some type of analysis of what those prices may be to achieve different targets.[104]

Carbon price

3.82

The carbon price was forecast to increase electricity prices by around

10 per cent[105]

and that appears to be occurring in practice: witnesses cited figures of six,[106]

9.5,[107]

10[108]

and 15 per cent.[109]

Network investment and gold plating

3.83

Of all the areas potentially responsible for electricity price rise

network investment appears to be the largest and is therefore attracting a lot

of attention. The Productivity Commission pointed to NSW electricity bills

between 2007–08 and 2012–13 in which a typical total bill went from $1100 to

$2230, with the network component growing by 130 per cent from $505 to $1159.[110]

In other words, the network component in 2012–13 is now more than the total

bill was in 2007–08.

3.84

The Prime Minister noted that current regulatory arrangements create an incentive

to overinvest in infrastructure and pass on the costs to consumers.[111]

Part of this is perceived by some to be associated with the merits review

process being too easy and the automatic additions of assets to

the regulated assets base;[112]

the department noted its observations regarding the impact of network costs on

electricity prices:

The department is obviously aware of recent increases in

electricity prices for consumers and we are aware that rising network charges

are a common driver as significant investment is required in new and ageing

networks to meet rising demand and ensure supply reliability.

Climate change policies have also put

upward pressure on prices, but we note the government is providing targeted

assistance to help households adjust to cost increases arising from the carbon

price.[113]

3.85

The committee received lots of submissions and oral evidence on the

over-investment in networks. For example, Dr Ray Challen of the Department of

Finance (Western Australia) stated '...I agree that there is that incentive for

over-investment in network assets'.[114]

Other examples included:

The protected monopoly companies take the opportunity to

overinvest or "gold plate" their networks because the regulatory

regime has encouraged them to do so.[115]

To date the NEM has conveyed efficient pricing signals and

delivered the necessary investment in the right place at the right time. In

real terms, the wholesale prices for electricity have not increased over the

life of the NEM. The competitive generation market has also responded very

quickly to the changed outlook; however, regulated investment has not.[116]

The growth in capital expenditure over

the past five years in networks has therefore outstripped the growth in both

energy and peak demand and contributed to those rises in retail prices. While

some of that expenditure has been necessary to deal with ageing assets, it is

not clear that all the expenditure is supported by either the age of the

network assets or the growth in demand.[117]

So the problem with the increased network spend and the

flattening or even decreasing sale of kilowatt hours is a structural issue. It

costs you more to sell less of your product, and therefore prices will

inevitably spiral.[118]

[T]he important thing is the network spend. It is just far

and away the biggest component of the bill increase, so it has to be, I would

suggest, the most significant thing that you would focus your attention on.[119]

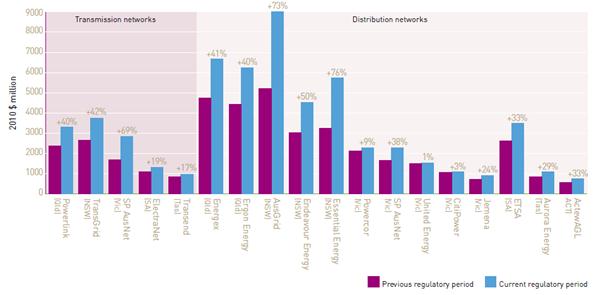

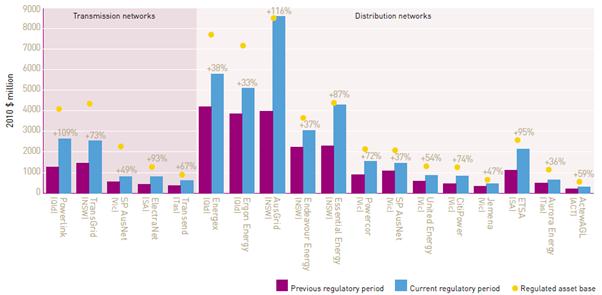

3.86

The AER's 2011 State of the Energy Market report showed that

NSPs' revenue has been increasing in line with increasing network investment

(see Figures 3.10 and 3.11).

Figure 3.10: Energy network revenue[120]

Figure 3.11: Energy network

investment[121]

3.87

In contrast to much of the evidence presented to the committee, SP

AusNet indicated that in their view there are instances where network costs

have fallen, such as in Victoria.[122]

Grid Australia also noted that investment in transmission infrastructure has

not been as great as in distribution infrastructure and that it can assist in

lowering electricity prices:

Grid Australia members are currently spending at or below

approved forecast expenditure needs for their current regulatory control

periods. This is consistent with and responsive to demand in growth that is

generally below forecast expectations. In some cases this is a result of

deferred expenditure on identified projects. It is also worth noting that the

Australian Energy Regulator—the AER—has found that transmission investment is

forecast to plateau for transmission businesses this year. This is in contrast

to the AER's prediction that distribution network costs will continue to rise.[123]

Unlike distribution networks though, strategic investment in

transmission helps increase interstate electricity trade and generator competition,

getting consumers the lowest cost and efficient generation and, in doing so,

helping to reduce power price rises.[124]

3.88

Some of the arguments against the existence of gold-plating include that

other methods, such as new minimum service standards and demand reduction

activities, have permitted reductions in capital expenditure:

Energex has worked with the Queensland government through the

second Somerville review during 2011 to assess the effectiveness of the

security and reliability standards. As a result of this review, the minimum

service standards have been stabilised or flat-lined and the security standards

have been broadened to provide more efficient options. Together, the adoption

of these changes in conjunction with the forecast moderation in network demand

growth compared to previous forecasts has allowed us to reduce our capital

expenditure over the current regulatory period by a further $850 million. The

benefits of these expenditure reductions have been passed through in our

network charges in the form of price discounts in 2012-13.[125]

3.89

Other arguments against gold-plating having occurred postulate that

external factors beyond the control of the network businesses are to blame:

ENA's submission explains how a perfect storm of high capital

costs, higher government reliability standards, replacement of ageing assets

and the need to service rising peak demand have all combined to push up network

costs. ENA members appearing before the committee have explained that these

factors are likely to moderate in the near term. Many businesses expect that

future cost increases will be in line with inflation or perhaps even lower.[126]

[R]egulation to hold down retail electricity prices is

self-defeating because the true costs of electricity need to be met somewhere,

either through electricity prices [or] through the taxation system. Since

regulated prices rarely keep pace with market developments, built up pressures

can lead to sudden changes, larger than those the market would produce.[127]

3.90

Others informed the committee that, in their view, the regulatory

arrangements were more at fault than the businesses. For example, Dr Paul

Troughton argued that 'I am not accusing anyone of acting badly...Everyone is

just responding to the incentives that are in place in the existing regime'.[128]

3.91

The Productivity Commission suggested that 'it is important not to blame

network businesses for the current inefficiencies. Mostly, they are responding

to regulatory incentives and structures that impede their

efficiency'.[129]

3.92

Professor Garnaut elaborated on the reasons for the regulatory failure

and observed that the high rate of return was very likely to cause wasteful

over-investment and upward pressure on prices:

Excessive price increases have reduced demand, and we

guarantee a rate of return under our rate-of-return regulation. It is basically

a riskless rate of return; there is not even exposure to the market...A completely

unsustainable situation can emerge and I think that we are in that

unsustainable situation now.[130]

3.93

The committee heard that some steps are already being taken to address

the regulatory issues (these are discussed further in the next chapter):

The other thing that is important to note is the regulation

of networks has been subject to a recent rule change proposal. That has been

under consideration by the Australian Energy Market Commission and continues to

be under consideration by the Australian Energy Market Commission... there is a

draft ruling out at the moment. We would expect a final ruling by the end of

the year.[131]

Committee comment

3.94

The committee has been informed about a large number of factors which

contribute to electricity prices and recent increases in these. Some of these

factors are contested, while others have wider acceptance. For some factors,

while the price increases may seem perverse to somebody outside the electricity

industry, it is apparent to the committee these have probably arisen as a

result of historical technical and regulatory artefacts.

3.95

The committee considers that the following factors (shaded factors in

Figure 3.3) have made significant contributions to household electricity

prices rises:

(a) peak demand;[132]

(b) overestimated demand forecasts;

(c) opportunistic profit taking;

(d) gold-plating of networks;

(e)dividend extraction by state governments;

(f) revenue caps causing price to rise when demand falls;

(g) hedging arrangements to protect against price volatility in the NEM;

(h) labour prices;

(i) greater use of underground cabling;

(j) replacement of assets after their useful life;

(k) lack of competition in some retail sectors; and

(l) unwinding of cross subsidies between business and household customers.

3.96

The committee notes that factors (a) to (f) above are strongly

influenced and enabled by the current regulatory arrangements which have set

regulated returns at too high a level, as described by Professor Garnaut.[133]

The committee further notes that the other unshaded factors in Figure 3.3 may

have also contributed to electricity prices.

3.97

While the committee is convinced of the contributions to electricity prices

discussed above, the committee is concerned that efforts to address these

issues are hampered by a lack of quantitative information about their exact

contribution. The committee notes the useful breakup of contributions to future

electricity prices provided by the AEMC, which includes factors such as

transmission, distribution, wholesale, retail, carbon price, feed-in tariffs

(FiTs), LRET, SRET and other state based schemes (see the discussion earlier in

this chapter for the contributions). However, this does not provide sufficient

information about other factors.

3.98

The committee therefore considers that it would be very beneficial if

the AER was to provide more detailed ongoing quantitative monitoring of a much

broader range of the factors contributing to electricity prices, including

those identified in this report.

Recommendation 1

3.99

The committee recommends that the AER provide an annual report

including detailed quantitative analysis of the components of and contributors

to electricity prices.

3.100

The committee observed that for many factors contributing to electricity

price rises, where the information and evidence around those individual factors

is considered in isolation, the price increases may seem appropriate and

logical. However, the overall electricity price increases experienced by

Australians are completely inappropriate and unacceptable. The ATA noted that:

Whilst there are many improvements that would reduce prices

for consumers, a fundamental problem with the disaggregated structure of the

energy market is that typically no single business can make a sound business

case to promote any one of these improvements for consumers, based on the

benefits to their part of the supply chain.[134]

3.101

From the committee's perspective, many stakeholders have appeared to

argue that the price rises occurring in their components or factors are fair

and logical, while the price rise of other components is the real problem. The

committee considers that there needs to be a greater collective responsibility

taken for overall electricity prices. This view is supported by a report

commissioned by the CALC:

The draft report provides a comprehensive overview of policy

and regulatory developments with a specific focus on wholesale and retail

markets, demand side interaction, market structure and efforts to tackle carbon

emission reductions. The draft report argues that in Australia at present,

consumer welfare is given insufficient attention by Australian policy makers

and regulators, and throughout the report recommendations are made to inform a

policy and regulatory framework that has a more rigorous focus on the interests

of consumers. The draft report draws on international development, particularly

from Europe and the UK, where there has been acknowledgment that the interests

of industry did not 'trickle down' to satisfy the needs of consumers.[135]

3.102

The committee supports the related conclusion and way forward proposed

by the Productivity Commission:

The overarching objective of the regulatory regime is the

long-term interests of electricity consumers. This objective has lost its

primacy as the main consideration for regulatory and policy decisions. Its

pre-eminence should be restored by giving consumers much more power in the

regulatory process.[136]

3.103

The committee is therefore of the view that there needs to be better

ongoing arrangements for managing electricity prices in the overall electricity

system to ensure that price setting for individual components and factors is

done in the context of keeping overall electricity price rises and the rate at

which these occur at a more acceptable level. In other words, the committee

recommends that those bodies setting prices at the individual component or

factor level should have regard to and justify the impact on overall

electricity prices.

Recommendation 2

3.104

The committee recommends that ongoing arrangements be put in

place to more effectively scrutinise prices in the overall electricity system,

and ensure that price setting for individual components and factors is done in

the context of keeping overall electricity prices at a more acceptable level.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page