Bills—the parliamentary process

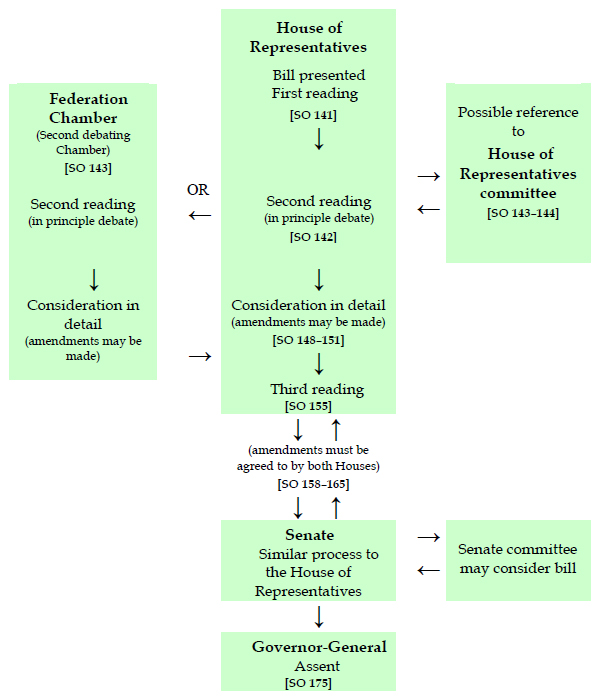

The normal flow of the legislative process is that a bill (a draft Act, or, in the terminology of the Constitution, a proposed law) is introduced into one House of Parliament, passed by that House and agreed to (or finally agreed to when amendments are made) in identical form by the other House. At the point of the Governor-General’s assent a bill becomes an Act of the Parliament.[4] (The legislative process is presented in diagrammatic form on the back inside cover.)

In the House of Representatives all bills are treated as ‘public bills’—that is, bills relating to matters of public policy. The House of Representatives does not recognise what in the United Kingdom and some other legislatures are called ‘private bills’[5]—that is, bills for the particular interest or benefit of any person or persons, public company or corporation, or local authority. Hence there is also no recognition of what are termed ‘hybrid bills’—that is, public bills to which some or all of the procedures relating to private bills apply.[6]

On average, about 200 bills have been introduced into the Parliament each year in recent years (the figure for 2011 was 265). Of these roughly 90 per cent (84 per cent in 2011) have usually originated in the House of Representatives.[7] Approximately 80 per cent (72 per cent in 2011) of all bills introduced into the Parliament finally become Acts.[8] The consideration of legislation takes up some 55 per cent of the House’s time (49 per cent in 2011).

Provided the rules relating to initiation procedures are observed any Member of the House may introduce a bill. Until more recent times there were only limited opportunities for private Members to introduce bills, but in 1988 new arrangements were adopted and more opportunities became available (see Chapter on ‘Non-government business’).

Form of bill

The content of a bill is prepared in the exact form of the Act it is intended to become.[9] Bills usually take the form described below, although it should be noted that not all the parts are essential to every bill. The parts of a bill appear in the following sequence:

Long title

Every bill begins with a long title which sets out in brief terms the purposes of the bill or may provide a short description of the scope of a bill. The words commencing the long title are usually either ‘A Bill for an Act to …’ or ‘A Bill for an Act relating to …’. The term ‘long title’ is used in distinction from the term ‘short title’ (see page 346). A procedural reference to the ‘title’ of a bill, without being qualified, may be taken to mean the long title. The long title is part of a bill and as such is capable of amendment[10] and must finally be agreed to by each House. The long title of a bill is procedurally significant. Standing orders require that the title of a bill must agree with its notice of presentation, and every clause must come within the title.[11] In 1985 and 2002 bills were withdrawn when it was discovered that the long title on the introduced copy was different from the notice—immediately afterwards replacement bills with the correct long title were presented by leave.[12] In 1984 a bill was withdrawn as not all the clauses fell within the scope of the bill as defined in the long title.[13] Difficult questions can arise in this area.[14] A long title which is specific and limited in scope is known as ‘restricted’, and one which is wide in scope as ‘unrestricted’. This distinction has significance in relation to relevance in debate on the bill (see page 364) and to the nature of amendments which can be moved to the bill (see page 376).

Preamble

Like the long title, a preamble is part of a bill, but is a comparatively rare incorporation. The function of a preamble is to state the reasons why the enactment proposed is desirable and to state the objects of the proposed legislation.

The Australia Act 1986 contains a short preamble stating that the Prime Minister and State Premiers had agreed on the taking of certain measures (as expressed in the Act’s long title) and that in pursuance of the Constitution the Parliaments of all the States had requested the Commonwealth Parliament to enact the Act. The Norfolk Island Act 1979, the Native Title Act 1993, and the Natural Heritage Trust of Australia Act 1997 are examples of Acts with longer preambles.

Some bills contain objects or statement of intention clauses, which can serve a similar purpose to a preamble—see for example clause 3 of the Space Activities Bill 1998.[15] Section 15AA of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 provides that in the interpretation of an Act a construction that would promote the purpose or object underlying the Act, whether expressly stated or not, must be preferred (and see page 400).

Enacting formula

This is a short paragraph which precedes the clauses of a bill. The current words of enactment are as follows:

‘The Parliament of Australia[16] enacts:’

The words of enactment have changed several times since 1901. Prior to October 1990 they were:

‘BE IT ENACTED by the Queen, and the Senate and the House of Representatives of the Commonwealth of Australia, as follows:’

Commenting on the original enacting formula, Quick and Garran stated:

In the Constitution of the Commonwealth the old fiction that the occupant of the throne was the principal legislator, as expressed in the [United Kingdom] formula, has been disregarded; and the ancient enacting words will hereafter be replaced by words more in harmony with the practice and reality of constitutional government. The Queen, instead of being represented as the principal, or sole legislator, is now plainly stated [by section 1 of the Constitution] to be one of the co-ordinate constituents of the Parliament.[17]

Clauses

Clauses may be divided into subclauses, subclauses into paragraphs and paragraphs into subparagraphs. Large bills are divided into Parts which may be further divided into Divisions and Subdivisions.[18] When a bill has become an Act—that is, after it has received assent—clauses are referred to as sections.

Short title

The short title is a convenient name for the Act, a label which assists in identification and indexing.[19] Clause 1 of a bill usually contains its short title, and this clause describes the measure in terms as if the bill had been enacted, for example, ‘This Act may be cited as the[20] Crimes at Sea Act 1999’. Since early 1976 a bill amending its principal Act or other Acts has generally included the word ‘Amendment’ in its short title. When a session[21] of the Parliament extends over two or more calendar years and bills introduced in one year are not passed until an ensuing year, the year in the citation of the bill is altered to the year in which the bill finally passes both Houses.[22] This formal amendment may be effected before transmission to the Senate after the passing of the bill by the House (when there may be a need to reprint the bill because it has been amended by the House) or before forwarding for assent.

It is not uncommon for more than one bill, bearing virtually the same short title, to be introduced, considered and enacted during the same year.[23] In this situation the second bill and subsequent bills are distinguished by the insertion of ‘(No. 2)’, ‘(No. 3)’, and so on, before the year in the short title.[24] Bills dealing with matters in a common general area may be distinguished with qualifying words contained in parenthesis within the short title.[25] In both these cases the distinguishing figures or words in the short title flow to the Act itself and its citation.

On other occasions a bill may, for parliamentary purposes, carry ‘[No. 2]’ after the year of the short title to distinguish it from an earlier bill of identical title. Identical titles may be used, for example, when it is known that the earlier bill will not further proceed in the parliamentary process to the point of enactment or when titles are expected to be amended during the parliamentary process.[26] Identical titles have also occurred when the same bills have been introduced in both Houses.[27] This distinction in numbering also becomes necessary for bills subject to inter-House disagreement, in the context of the constitutional processes required by sections 57 and 128 of the Constitution. There have also been ‘[No. 3]’ bills.[28]

Commencement provision

In most cases a bill contains a provision as to the day from which it has effect. Sometimes differing commencement provisions are made for various provisions of a bill—when this is the case modern practice is to set the details out in a table. Where a bill has a commencement clause, it is usually clause 2, and the day on which the Act comes into operation is usually described in one of the following ways:

- the day on which the Act receives assent;

- a date or dates to be fixed by proclamation (requiring Executive Council action). The proclamation must be published in the Gazette. This method is generally used if it is necessary for preparatory work, such as the drafting of regulations, to be done before the Act can come into force. Proclamation may be dependent on the meeting of specified conditions;[29]

- a particular date (perhaps retrospective) or a day of a stipulated event (e.g. the day of assent of a related Act); or

- a combination of the above (e.g. sections/schedules 1 to 6 to come into operation on the day of assent, sections/schedules 7 to 9 on a date to be proclaimed).[30]

Unusual commencement dates have included:

- the day after the day on which both Houses have approved regulations made under the Act;[31]

- a ‘designated day’, being a day to be declared by way of a Minister’s statement tabled in the House.[32]

Since 1989 it has been the general practice with legislation commencing by proclamation for commencement clauses to fix a time at which commencement will automatically take place, notwithstanding non-proclamation. Alternatively, the commencement clause may fix a time at which the legislation, if not proclaimed, is to be taken to be repealed.[33]

In the absence of a specific provision, an Act comes into operation on the 28th day after the day on which the Act receives assent.[34] This period acknowledges the principle that it is undesirable for legislation to be brought into force before copies are available to the public. Modern practice is to include an explicit commencement provision in each bill. Acts to alter the Constitution, unless the contrary intention appears in the Act, come into operation on the day of assent.

An Act may have come into effect according to its commencement clause, yet have its practical operation postponed, for example pending a date to be fixed by proclamation.[35] It is also possible for provisions to operate from a day to be declared by regulation. As regulations are subject to potential disallowance by either House, this practice may not commend itself to Governments. The Australia Card Bill 1986, having passed the House, was not further proceeded with following the threat of such a disallowance in the Senate.[36]

Activating clause

When provisions of a bill are contained in a schedule to the bill (see below), they are given legislative effect by a provision in a preceding clause. Current practice is for the insertion of an ‘activating’ clause at the beginning of the bill (usually clause 3) providing typically that each Act specified in a schedule is amended or repealed as set out in the schedule and that any other item in a schedule has effect according to its terms.

Definitions

A definitions or interpretation clause, traditionally located early in the bill, sets out the meanings of certain words in the context of the bill. Definitions may also appear elsewhere in a bill and for ‘amending’ bills will be included in schedules. At the end of some bills there may be a ‘dictionary’ clause defining asterisked terms cited throughout the bill.

Substantive provisions

Traditionally, the substantive provisions of bills were contained in the remaining clauses. This is still the practice in respect of ‘original’ or ‘parent’ legislation. In the case of bills containing amendments to existing Acts, the modern practice is to have only minimal provisions in the clauses (such as the short title and commencement details) and to include the substantive amendments in one or more schedules.

Schedules

Historically schedules have been used to avoid cluttering a bill with detail or with material that would interfere with the readability of the clauses. In earlier times amending bills commonly included schedules setting out amendments that, because of their nature, could more conveniently be set out in a schedule rather than in the clauses of a bill. During the 37th Parliament the practice started of including in schedules all amendments to existing Acts, whether amendments of substance or of less important detail. Office of Parliamentary Counsel Drafting Direction No. 1 of 1996 made it the standard practice in respect of government bills for all amendments and repeals of Acts to be made by way of numbered items in a schedule. Other items may be included in an amending/repealing schedule (e.g. transitional provisions). Other examples of the types of material to be found in schedules are:

- the text of a treaty to be given effect by a bill;

- a precise description of land or territory affected by a bill; and

- detailed rules for determining a factor referred to in the clauses (for example, technical material in a bill dealing with the construction of ships and scientific formulas in a bill laying down national standards).

While a schedule may be regarded as an appendix to a bill, it is nevertheless part of the bill, and is given legislative effect by a preceding clause (or clauses) within the bill. Schedules are referred to as ‘Schedule 1’, ‘Schedule 2’, and so on.

Associated documentation

Bills may also contain or be accompanied by the following documentation which, although not part of the bill and not formally considered by Parliament, may be taken into account by the courts, along with other extrinsic material, in the interpretation of an Act (see page 400).

Table of contents

Since 1995 a table of contents has been provided for all bills.[37] This table lists section/clause numbers and section/clause headings under Part and Division headings. The Table of Contents remains attached to the front of the Act.

Headings and notes

Previously, elements such as marginal notes, footnotes, endnotes and clause headings were not taken to be part of the bill. Following amendments to the Acts Interpretation Act in 2011, all material from and including the first clause of a bill to the end of the last schedule to the bill is now considered to be part of the bill.[38]

Explanatory memorandum

An explanatory memorandum is a separate document presenting the legislative intent of the bill in terms which are more readily understood than the bill itself. A memorandum usually consists of an introductory ‘outline’ of the general purposes of the bill and ‘notes on clauses’ which explain the provisions of each clause. When a number of interrelated bills are introduced together their explanatory memorandums may be contained in the one document.

Originally explanatory memorandums were prepared for certain complex bills only. These were circulated in the Chamber, but not presented to the House and thus not recorded in the Votes and Proceedings. Since 1983 it has been standard practice for departments to prepare explanatory memorandums for all government bills.[39] The practice (but not initially a standing orders requirement) of presenting explanatory memorandums formally was introduced in 1986 to facilitate court proceedings should an explanatory memorandum be required in court as an extrinsic aid in the interpretation of an Act, following the 1984 amendment to the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 which provided, among other things, that in the interpretation of a provision of an Act, consideration may be given to an explanatory memorandum.[40] Since 1994 the standing orders have required a Minister presenting a bill, other than an appropriation or supply bill, to present a signed explanatory memorandum.[41]

Statement of compatibility with human rights

Since 2012 it has been a legislative requirement that all bills and disallowable legislative instruments must be accompanied by a Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights, containing an assessment of whether the legislation is compatible with rights and freedoms recognised or declared by international treaties which Australia has ratified. The Member responsible for introducing a bill (including a private Member’s bill) must cause the statement to be prepared and to be presented to the House.[42] Generally such statements have been incorporated into the bill’s explanatory memorandum, but they may also be presented separately.

Comparative memorandum (black type bill)

A comparative memorandum is occasionally produced for the benefit of Members debating a bill.[43] This is a document that sets out the text of a principal Act as it would appear if a proposed amending bill were to be passed, and identifies the additions or deletions proposed to be made. Alternatively, it may set out differences between a current bill and an earlier version of the bill, or between a bill as introduced and as proposed to be amended. The term ‘black-type bill’ derives from the practice that new material is shown in bold type.

Preparation of bills—the extra-parliamentary process

Government bills usually stem either from a Cabinet instruction that legislation is required (that is, Cabinet is the initiator) or from a Minister with the advice of, or on behalf of, his or her department seeking (by means of a Cabinet submission) approval of Cabinet. The pre-legislative procedure in the normal routine,[44] regardless of the source of the legislative proposal, is that within five working days of Cabinet approval for the legislation being received by the sponsoring department, or within 10 working days if Cabinet has required major changes to be made to the original proposals, final drafting instructions must be lodged with the Office of Parliamentary Counsel[45] by the sponsoring department. Parliamentary Counsel drafts the bill and arranges for its printing.[46]

A copy of the draft bill is provided to the sponsoring department for its clearance, in consultation with other interested departments and instrumentalities, and the Minister’s approval. During these processes government party committees may be consulted. The procedures for such consultation vary, depending on the party or parties in government. When a proposed bill is finally settled, Parliamentary Counsel orders the printing of sufficient copies of the bill in the form used for presentation to Parliament and arranges for their delivery under embargo to staff of the House or the Senate.[47]

The Government’s Legislation handbook states that draft bills and all associated material are confidential to the Government and may not be made public before their introduction to the Parliament, unless disclosure is authorised by Cabinet or the Prime Minister.[48] Occasionally the Government may publish a draft bill and explanatory memorandum as an ‘exposure draft’ prior to its introduction to the Parliament.[49]

Synopsis of major stages

The stages through which bills pass are treated in detail in the pages which follow. Procedures for the passage of bills provide for the following stages:

- Initiation (S.O.s 138–140);

- First reading[50] (S.O. 141);

- Possible referral to the Federation Chamber for second reading and consideration in detail stages (S.O. 143(a));

- Possible referral to a standing or select committee for advisory report (S.O. 143(b));

- Report from standing or select committee (if bill referred) (S.O. 144);

- Second reading (S.O.s 142, 145–146);

- Announcement of any message from the Governor-General recommending appropriation (S.O. 147);

- Consideration in detail (S.O.s 148–151);

- Report from Federation Chamber and adoption (for bills referred to the Federation Chamber) (S.O.s 152–153);

- Reconsideration (possible) (S.O. 154);

- Third reading (S.O. 155);

- Transmission to the Senate for concurrence (S.O. 157);

- Transmission[51] or return of bill from the Senate with or without amendment or request (S.O.s 158–165);

- Presentation for assent (S.O.s 175–177).

Each of the stages of a bill in the House has its own particular function. The major stages may be summarised as follows:

Initiation: Bills are initiated in one of the following ways:

- On notice—The usual method of initiating a bill is by the calling on of a notice of intention to present the bill. The notice is prepared by the Office of Parliamentary Counsel, usually concurrently with the preparation of the bill. The notice follows a standard form:

I give notice of my intention to present, at the next sitting, a Bill for an Act [remainder of long title].

- The long title contained in the notice must agree with the title of the bill to be introduced. The notice must be signed by the Minister who intends to introduce the bill or by another Minister on his or her behalf. As with all notices, the notice of presentation must be given by delivering it in writing to the Clerk at the Table.

Stages a House bill goes through

- Without notice—In accordance with the provisions of standing order 178, appropriation or supply bills or bills (including tariff proposals) dealing with taxation may be presented to the House by a Minister without notice—see Chapter on ‘Financial legislation’.

- On granting of leave by the House—On occasions a bill may be introduced by the simple granting of leave to a Minister to present the bill.[52]

- Senate bills—A bill introduced into and passed by the Senate is conveyed to the House under cover of a message transmitting the bill for concurrence. The bill is, in effect, presented to the House by the Speaker’s action of reading out the message.

- Private Members’ bills intended for the Federation Chamber—If on Mondays the Speaker presents a bill for which notice has been given by a private Member, the first reading (later that day) is deemed to stand referred to the Federation Chamber.[53]

Standing order 138 also provides for initiation by order of the House. This procedure is no longer used.[54]

First reading: This is a formal stage only. On presentation of a bill the long title only is read immediately by the Clerk, and no question is proposed.[55]

Second reading: This is the stage primarily concerned with the principle of the legislative proposal. Debate on the motion for the second reading is not always limited to the contents of a bill and may include, for example, reasonable reference to relevant matters such as the necessity for, or alternatives to, the bill’s provisions. Debate may be further extended by way of a reasoned amendment.

Consideration in detail: At this stage, the specific provisions of the bill are considered and amendments to the bill may be proposed or made.

Third reading: At this stage the bill can be reviewed in its final form after the shaping it may have received at the detail stage. When debate takes place, it is confined strictly to the contents of the bill, and is not as wide-ranging as the second reading debate. When a bill has been read a third time, it has passed the House.[56]

Classification of bills

Bills introduced into the House may, for procedural purposes, be described as follows:

- Bills, by which no appropriation is made or tax imposed (‘ordinary’ bills);

- Bills containing special appropriations;

- Appropriation and supply bills;

- Bills imposing a tax or charge;

- Bills to alter the Constitution;

- Bills received from the Senate.

Table 10.1 Procedures applying to different categories of bills

Description

| Special nature

| Provisions of Constitution and standing orders relevant to classa

| Major stages followed in respect of class b

|

ORDINARY

Examples Acts Interpretation Bill, Trade Practices Bill, Parliamentary Papers Bill.

| Bills that:

(a) do not contain words which appropriate the Consolidated Revenue Fund;

(b) do not impose a tax; and

(c) do not have the effect of increasing, or altering the destination of, the amount that may be paid out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund under existing words of appropriation in an Act.

| Constitution ss. 53, 57, 58, 59, 60.

S.O.s 138–164, 174–176.

| Initiation on notice of intention to present; sometimes by leave; bills dealing with taxation may be presented without notice. Explanatory memorandum presented.

First reading; Clerk reads title; no debate allowed.

Second reading moved immediately (usually); Minister makes second reading speech; debate adjourned to a future day.

Bill may be referred to Federation Chamber for remainder of second reading and detail stage, or to a standing or select committee for an advisory report.

Second reading debate resumed; reasoned amendment may be moved; second reading agreed to; Clerk reads title.

Consideration in detail immediately following second reading. Amendments may be made.

(Report by Federation Chamber to House, if bill referred; House adopts report.)

Third reading moved; may be debated; agreed to; Clerk reads title. Message sent to Senate seeking concurrence.

NOTE: Detail stage is often bypassed.

|

SPECIAL APPROPRIATION

Examples

(a) States Grants Bill;

(b) An amending Judiciary Bill to alter the remuneration of Justices as stated in the principal Act.

| Bills that:

(a) contain words which appropriate the Consolidated Revenue Fund to the extent necessary to meet expenditure under the bill; or

(b) while not in themselves containing words of appropriation, would have the effect of increasing, or altering the destination of, the amount that may be paid out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund under existing words of appropriation in an Act.

| Constitution ss. 53, 56.

S.O.s 147, 180–182.

| Initiation on notice of intention to present, sometimes by leave.

Proceedings same as for ordinary bills except that immediately following second reading—

Message from Governor-General recommending appropriation for purposes of bill is announced and if required in respect of anticipated amendments to be moved during detail stage, a further message for the purposes of the proposed amendments is announced.

Subsequent proceedings same as for ordinary bills.

|

APPROPRIATION AND SUPPLY

Examples

Appropriation Bills (No. 1) and (No. 2) Supply Bills (No. 1) and (No. 2).

| Appropriation Bills appropriating money from the Consolidated Revenue Fund (usually) for expenditure for the year.

If necessary, Supply Bills appropriating money from the Consolidated Revenue Fund to make interim provision for expenditure for the year pending the passing of the Appropriation Bills.

| Constitution ss. 53, 54, 56.

S.O.s 165, 178, 180(b).

| Message from Governor-General recommending appropriation announced prior to introduction. If required a further message for the purposes of proposed amendments is announced prior to consideration in detail.

Initiation without notice.

Proceedings otherwise same as for ordinary bills other than for sequence in detail stage.

|

TAXATION

Examples

Income Tax Bills and Customs and Excise Tariff Bills.

| Bills imposing a tax or a charge in the nature of a tax.

| Constitution ss. 53, 55.

S.O.s 165, 178, 179.

| Initiation without notice.

Proceedings same as for ordinary bills.

Only Minister may move amendments to increase or extend taxation measures.

NOTE: Governor-General’s message is not required.

|

CONSTITUTION ALTERATION

Example

Constitution Alteration (Establishment of Republic) 1999.

| Bills to alter the Constitution.

| Constitution s. 128.

S.O. 173

| Same as for ordinary bills but with additional requirement for bill to be passed by absolute majority.

|

SENATE INITIATED

Examples

Same as for ordinary bills.

| Same as for ordinary bills.

| Constitution s. 53.

S.O.s 166–171.

| Message from Senate reported transmitting bill to House for concurrence.

First reading; second reading moved; debate adjourned.

Subsequent proceedings same as for ordinary bills.

(Senate bills sometimes referred to Federation Chamber before moving of second reading.)

Message sent to Senate notifying House agreement or, if amended, seeking Senate concurrence in amendments.

|

(a) Sections 57 to 60 apply to all categories and standing orders relevant to ordinary bills generally apply to all categories.

(b) Regular or normal proceedings.

The procedures in the House for all bills have a basic similarity. The passage of a bill is, unless otherwise ordered, always in the stages of first reading, second reading, consideration in detail and third reading. For the purposes of this text procedures common to all classes of bills are described in detail under ordinary bills. As is evident in Table 10.1, significant variations or considerations apply to bills in other categories and they are described when that category is examined.

Ordinary bill procedure

‘Ordinary’ bills for procedural purposes are those which:

- do not contain words which appropriate the Consolidated Revenue Fund;

- do not have the effect of increasing, or altering the destination of, the amount that may be paid out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund under existing words of appropriation in an Act; and

- do not impose a tax (an ordinary bill may ‘deal with’ taxation without imposing it— see Chapter on ‘Financial legislation’).

Initiation and first reading

Ordinary bills are usually introduced by notice of intention to present or sometimes by leave.[57] Ordinary bills ‘dealing with taxation’ may be introduced without notice.[58] When the notice of intention to present the bill is called on by the Clerk, the Minister (or Parliamentary Secretary[59]) in charge of the bill rises and says ‘I present the [short title of bill]’. The Minister then hands a signed[60] copy of the bill to the Clerk. This copy becomes the ‘original’ or ‘model’ copy of the bill.

It is the practice of the House that another Minister may present a bill for a Minister who has given notice.[61] When the notice is called on by the Clerk, the Minister who is to present the bill rises and says ‘On behalf of the . . . , I present the [short title]’.[62]

There is no requirement for a Minister (or any Member) introducing a bill to present a printed copy. The standing order requires only that a legible copy signed by the Minister be presented to the House. Nevertheless printed copies are usually available when the bill is introduced. Immediately after presenting the bill the Minister presents the bill’s explanatory memorandum.[63]

The Clerk, upon receiving the copy of the bill from the Minister and without any question being put,[64] formally reads the bill a first time by reading its long title.[65] Once a bill is presented, it must be read a first time.[66] The long title of the bill presented must agree with the title used in the notice of intention to present, and every clause of the bill must come within its title.[67] Any bill presented and found to be not prepared according to the standing orders shall be ordered to be withdrawn.[68]

Bills have been withdrawn because:

- the long title did not agree with the long title given on the notice of presentation;[69]

- several clauses did not come within its long title;[70] and

- the long title described in the Governor-General’s message recommending appropriation did not agree with the long title.[71]

A bill is not out of order if it refers to a bill that has not yet been introduced,[72] and a bill may be introduced which proposes to amend a bill not yet passed.[73]

As no question is proposed or put, no debate can take place at the first reading stage. However, special provisions apply to the first reading of private Member’s bills and the Member presenting the bill may make a statement at this time (see page 385).

Immediately after the first reading the usual practice is that the Minister moves that the bill be read a second time and makes the second reading speech. Copies of the bill and the explanatory memorandum are made available to Members in the Chamber. A bill is treated as confidential by the staff of the House until it is presented, and no distribution is made until that time. As soon as practicable after presentation the terms of bills and explanatory memoranda are made available on the Parliament’s website.[74] Leave has been given for the presentation of a replacement copy of a bill after it was learnt that there were printing errors in the copy presented originally.[75]

The application of the same motion rule to bills

The Speaker has the discretionary power under standing order 114(b) to disallow any motion which he or she considers is the same in substance as any question already resolved during the same session. Proceedings on a bill are taken to be ‘resolved’ in this context when a decision has been made on the second reading, and the rule does not prevent identical bills merely being introduced. Sections 57 (double dissolution) and 128 (constitution alteration) of the Constitution, relating to the resolution of disagreements between the Houses, provide for the same bills to be passed a second time after an interval of three months.[76] These provisions override the standing order.[77]

In using his or her discretion in respect of a bill the Speaker would pay regard to the purpose of the rule, which is to prevent obstruction or unnecessary repetition, and the reason for the second bill. Hence, in addition to the cases provided for in the Constitution, a Speaker might not seek to apply the rule to cases arising from Senate disagreement, and in the normal course of events it is only on such occasions that a bill would be reintroduced in the House and passed a second time.[78] For example, there have been occasions when the Senate has rejected bills transmitted from the House,[79] or delayed their passage,[80] and the House has again passed the bills without waiting the three months period. In one case the standing order providing for the same motion rule was suspended,[81] although in view of the Speaker’s discretion in this matter the suspension may not have been necessary. It is also possible that a bill could seek to reintroduce provisions of a bill previously passed by the House but subsequently deleted from the bill by Senate amendment.[82]

Although there is no record of a motion on a bill being disallowed under the same question rule, in some circumstances the operation of the rule would be appropriate. In 1982 two identical bills were listed on the Notice Paper as orders of the day, one a private Member’s bill and the other introduced from the Senate. Had either one of the bills been read a second time, or the second reading been negatived, any further consideration of the other bill would have been preventable under the same question rule, but in the event neither bill was proceeded with.[83]

A number of private Members’ bills which have lapsed pursuant to the provisions of standing order 42 have been put forward again. As no resolution had been reached on the previous occasion, the same motion rule was not applicable.[84]

Referral to Federation Chamber

After the first reading but before the debate on the motion for the second reading is resumed, a motion may be moved without notice to refer the bill to the Federation Chamber[85] for the remainder of the second reading and consideration in detail stages. Bills may be referred by motion on notice or by leave after the resumption of debate on the second reading.[86] A motion may provide for referral at a future time.[87] An amendment has been moved to a motion of referral.[88] The Chief Government Whip, pursuant to powers bestowed by standing order 116(c) in relation to the conduct of business, rather than a Minister, usually moves the relevant motion. Generally the Chief Government Whip presents a list of bills proposed to be referred and moves a single motion, by leave, that bills be referred in accordance with the list.

When these procedures were first introduced in 1994, referral occurred between the first and second reading stages. The standing order was revised in 1996 to allow, but not compel, referral following the Minister’s second reading speech, and this has become the usual practice.[89] In cases where the second reading has not been moved immediately following the first reading (e.g. bills introduced from the Senate), bills have continued to be referred between the first and second reading stages, and Ministers’ second reading speeches on these bills are delivered in the Federation Chamber.[90]

Proceedings in the Federation Chamber

The Federation Chamber is an extension of the Chamber of the House, operating in parallel to allow two streams of business to be debated concurrently. It is an alternative venue rather than an additional process. For a description of Federation Chamber procedures generally see Chapter on ‘Motions’.

In respect of legislation, proceedings in the Federation Chamber are substantially the same as they are for the same stage in the House. A significant difference, stemming from the lack of opportunity in the Federation Chamber for divisions, is the provision for the ‘unresolved question’. Proceedings on a bill may be continued regardless of unresolved questions unless agreement to an unresolved question is necessary to enable further questions to be considered. If progress cannot be made the bill is returned to the House.[91]

At the conclusion of the bill’s consideration in detail the question is put, immediately and without debate, ‘That this bill be reported to the House, without amendment’ or ‘with (an) amendment(s)’ (‘and with (an) unresolved question (s)’), as appropriate.[92] If the Federation Chamber does not desire to consider the bill in detail it may grant leave for the question ‘That this bill be reported to the House without amendment’ to be moved immediately following the second reading.[93]

A bill may be returned to the House at any time during its consideration by the Federation Chamber by any Member moving, without notice or the need for a seconder, ‘That further proceedings be conducted in the House’.[94] A bill may also be recalled to the House at any time by motion moved in the House (also without notice or need for seconder).[95]

Referral to standing or select committee

Referral for advisory report

After the first reading but before the debate on the motion for the second reading is resumed, a bill may be referred by determination of the Selection Committee to a standing or joint committee for an advisory report.[96] The committee reviews bills as they are introduced and selects for referral those that it regards as controversial or as requiring further consultation or debate. The determination may specify a date by which the committee is to report to the House.[97]

Bills are referred to the general purpose standing committee or to the joint committee[98] most appropriate to the subject area of the bill. The participation of Members who are interested in the bill but not on the committee is facilitated by the provision that, for the purpose of consideration of bills referred for advisory reports, one or more members of the committee may be replaced by another Member.[99] In addition the normal provision for the appointment of supplementary members to a standing committee for a particular inquiry also applies.[100]

Committee proceedings on a bill are similar to proceedings on other committee inquiries; the committee may invite submissions and hold public hearings, and may refer the bill to a subcommittee. The committee’s recommendations are reported to the House[101] in the same manner as other committee reports, with committee members expecting to be able to make statements. Motions to take note of the report are not moved however, as opportunity for debate will occur during subsequent consideration of the bill if it is proceeded with.

After the committee has presented its report, and if the bill is to be proceeded with, the (remainder of the) second reading and the consideration in detail stages will follow in the House, or the bill may be referred for these stages to the Federation Chamber. The bill cannot be considered in detail until the committee has reported.[102] The time for the consideration in detail stage is set by a motion moved (without notice) by the Member in charge of the bill.[103] Although a formal government response may be presented,[104] the Government’s response to an advisory report may also be given by the Minister in speaking to the bill. If the Government accepts changes to the bill recommended in the advisory report, these are incorporated into government amendments moved during the consideration in detail stage.

Although the standing orders provide for bills to be referred to a committee before the resumption of debate on the motion for the second reading, referral at other times (e.g. during debate on the second reading) may occur following a suspension of standing orders.[105]

Bill referred to select committee

Pre-2004 standing orders provided for the possible referral of a bill by the House to a select committee immediately following the second reading. No bills were so referred. However, two bills were referred to select committees following the suspension of standing orders. On the first occasion the bill was referred to a select committee during the consideration in detail stage.[106] On the other occasion a bill was referred during the second reading stage, immediately following the Minister’s second reading speech, to a joint select committee.[107]

The terms of reference of the Joint Select Committee on Gambling Reform established in 2010 provided for the committee to inquire into and report on, among other matters, any gambling-related legislation tabled in either House, either as a first reading or exposure draft.[108] In 2011 the Joint Select Committee on Australia’s Clean Energy Future Legislation was appointed to inquire into and report on the provisions of a package of 19 related bills.[109]

Bill referred directly by Minister

Standing order 215 establishing the general purpose standing committees provides for the referral, by the House or a Minister, of any matter, including a pre-legislation proposal or bill, for standing committee consideration. Bills have been referred to a committee by a Minister directly (that is, without action in the Chamber), prior to[110] or even after[111] its introduction to the House, rather than through the advisory report mechanism provided by standing order 143.

Attempted referral by second reading amendment

Proposals to refer bills to committees have been put forward in second reading amendments.[112] Such amendments have on all occasions been rejected by the House.

Second reading

The second reading is arguably the most important stage through which a bill has to pass. The whole principle of the bill is at issue at the second reading stage, and is affirmed or denied by a vote of the House.

Moving and second reading speech

Copies of a bill having been made available in the Chamber, the second reading may be moved immediately after the first reading (the usual practice) or at a later hour.[113] The arrangements for private Members’ bills provide that after the first reading, the motion for the second reading shall be set down on the Notice Paper for the next sitting.[114]

On the infrequent occasions when copies of the bill are not available, leave may be granted for the second reading to be moved immediately,[115] or at a later hour that day.[116] If leave is refused, the second reading is set down for the next sitting.[117] Alternatively standing orders may be suspended to enable the second reading to be moved immediately.[118]

If the second reading is not to be moved immediately or at a later hour, a future sitting is appointed for the second reading, and copies of the bill must then be available.[119] The House appoints, on motion moved by the Minister, the day (that is, the next sitting or some later date) for the second reading to be moved.[120] The motion is open to amendment and debate. An amendment must be in the form to omit ‘the next sitting’ in order to substitute a specific date or day. Debate on the motion or amendment is restricted to the appointment of a day on which the second reading is to be moved, and reference must not be made to the terms of the bill.[121] The second reading is set down as an order of the day on the Notice Paper for the next sitting or a specific date.[122]

During the 37th Parliament the House adopted the practice of having bills presented together with explanatory memorandums, with the second reading not being moved immediately following the first reading but being made an order of the day for the next sitting. When the order was called on on a later day, the Minister moved the second reading, delivered his or her second reading speech, and further debate followed immediately. This practice was discontinued on the recommendation of the Procedure Committee, which felt that it helped Members to have the terms of the Minister’s second reading speech available when preparing their own speeches.[123]

There may be reasons, other than the unavailability of printed copies of the bill, for the second reading to be set down for a future day. The Government may want to make public the terms of proposed legislation, with a view to enabling Members to formulate their position in advance of the Minister’s second reading speech and debate.[124]

The common practice, however, is for the second reading to be moved immediately after the bill has been read a first time. The terms of the motion for the second reading are ‘That this bill be now read a second time’[125] and in speaking to this motion the Minister makes the second reading speech, explaining, inter alia, the purpose and general principles and effect of the bill. This speech should be relevant to the contents of the bill.[126] The time limit for the Minister’s second reading speech (for all bills except the main appropriation bill for the year) is 30 minutes.[127] A second reading speech plays an important role in the legislative process and its contents may be taken into account by the courts in the interpretation of an Act (see page 400). Ministers are expected to deliver a second reading speech even if the speech has already been made in the Senate. It is not accepted practice for such speeches to be incorporated in Hansard.[128] At the conclusion of his or her speech the Minister sometimes presents documents connected to the bill, for example, a government response to a committee report on the bill.[129] Leave is not required for this or for the presentation of replacement memorandums or corrigendums.

When the second reading has been moved immediately pursuant to S.O. 142(a), it is mandatory[130] for debate to be adjourned after the Minister’s speech, normally on a formal motion of a member of the opposition executive. This motion cannot be amended or debated,[131] and as adjournment is compulsory, no vote is taken.[132] A further question is then put ‘That the resumption of the debate be made an order of the day for the next sitting’. This question is open to amendment and debate, although neither is usual. An amendment must be in the form to omit ‘the next sitting’ in order to substitute a specific day or date, for example, ‘Tuesday next’[133] or ‘11 December 1989’.[134] Debate on the question or amendment is restricted to the appointment of the day on which debate on the second reading is to be resumed and reference must not be made to the terms of the bill.

Resumption of debate

Debate may not be resumed for some time, depending on the Government’s legislative program, and during this time public and Members’ attitudes to the proposal may be formulated.

An order of the day set down for a specified day is not necessarily order of the day No. 1 for that day, nor does it necessarily mean that the item will be considered on that day.[135]

The fixing of a day for the resumption of a debate is a resolution of the House and may not be varied without a rescission (on seven days’ notice) of the resolution.[136] However, a rescission motion could be moved by leave or after suspension of standing orders. In 1973 the order of the House making the second reading of a bill an order of the day for the next sitting was rescinded on motion, by leave, and the second reading made an order of the day for that sitting.[137] The purpose of fixing ‘the next sitting’ or a specific future day ensures that, without subsequent action by the House, the order of the day will not be called on before the next sitting or the specified day.

On occasions debate may ensue, with the leave of the House, immediately after the Minister has made the second reading speech.[138] By the granting of leave, the mandatory provision of standing order 142(a) concerning the adjournment of the debate no longer applies, and a division may be called on any subsequent motion for the adjournment of the debate.[139] Alternatively, after the second reading speech, debate may, by leave, be adjourned until a later hour on the same day that the bill is presented.[140] If leave is refused in either of these cases, the same effect can be achieved by the suspension of standing orders.[141]

If the second reading has been set down for a future sitting day, on that day the Minister makes the second reading speech when the order of the day is called on, and debate may be adjourned by an opposition Member[142] in the normal way. Alternatively, the second reading debate may proceed immediately, as the provision concerning the mandatory adjournment of debate when the second reading has been moved immediately after the first reading does not apply.

As with all adjourned debates, when an adjourned second reading debate is resumed, the Member who moved the adjournment of the debate is entitled to the first call to speak.[143] However, usually it is the opposition spokesperson on the bill’s subject matter who resumes the debate, and this may not be the same Member who obtained the adjournment of the debate. On resumption of the second reading debate the Leader of the Opposition, or a Member deputed by the Leader of the Opposition—in practice a member of the opposition executive—may speak for 30 minutes. The Member so deputed, generally the shadow minister, is usually, but not necessarily, the first speaker when the debate is resumed. Other speakers in the debate may speak for 15 minutes, or for a lesser time determined by the Selection Committee.[144]

Nature of debate—relevancy

The second reading debate is primarily an opportunity to consider the principles of the bill and should not extend in detail to matters which can be discussed at the consideration in detail stage. However, it is the practice of the House to permit reference to amendments proposed to be moved at the consideration in detail stage. The Chair has ruled that a Member would not be in order in reading the provisions of a bill seriatim and debating them on the second reading,[145] and that it is not permissible at the second reading stage to discuss the bill clause by clause; the second reading debate should be confined to principles.[146]

However, debate is not strictly limited to the contents of the bill and may include reasonable reference to:

- matters relevant to the bill;

- the necessity for the proposals;

- alternative means of achieving the bill’s objectives;

- the recommendation of objectives of the same or similar nature; and

- reasons why the bill’s progress should be supported or opposed.

However, discussion on these matters should not be allowed to supersede debate on the subject matter of the bill.

When a bill has a restricted title and a limited subject matter, the application of the relevancy rule for second reading debate is relatively simple to interpret.[147] For example, the Wool Industry Amendment Bill 1977, the long title of which was ‘A Bill for an Act to amend section 28A of the Wool Industry Act 1972’,[148] had only three clauses and its object was to amend the Wool Industry Act 1972 so as to extend the statutory accounting provisions in respect of the floor price scheme for wool to include the 1977–78 season. Debate could not exceed these defined limits.[149] The Overseas Students Tuition Assurance Levy Bill 1993 was a bill for an Act to allow levies to be imposed by the rules of a tuition assurance scheme established for the purposes of section 7A of the Education Services for Overseas Students (Registration of Providers and Financial Regulation) Act 1991, and contained only three clauses, thus allowing only a limited scope for debate.

A more recent example of a bill with a restricted title was the Extension of Sunset of Parliamentary Joint Committee on Native Title Bill 2004, the long title of which was ‘A Bill for an Act to extend for 2 years the operation of the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Native Title and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Land Fund’. It also contained only three clauses.

To a lesser extent, the relevancy rule is easily interpreted for a bill with a restricted title to amend named parts of the principal Act, even though the bill may contain a greater number of clauses than the above examples. The Speaker ruled that the scope of debate on the States Grants (Special Financial Assistance) Bill 1953 should not permit discussion of the ways in which the States might spend the sums granted, that the limits of the debate were narrow and that he would confine the debate to whether the sums should be granted or not. The Speaker’s ruling was dissented from, following which the Speaker stated that the expenditure methods of the States were clearly open for discussion.[150] Examples of amending bills with restricted titles were the Ministers of State Amendment Bill 1988, the long title of which was ‘A Bill for an Act to amend section 5 of the Ministers of State Act 1952’,[151] and the Veterans’ Entitlements Amendment (Male Total Average Weekly Earnings) Bill 1998, its long title being ‘A Bill for an Act to amend section 198 of the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986 to allow increases in the rate of pension payable under paragraph 30(1)(a) of that Act to the widow or widower of a deceased veteran to take account of Male Total Average Weekly Earnings’.

When a bill has an unrestricted title, for example, the Airports Bill 1995, whose long title was ‘A Bill for an Act about airports’ and which contained a large number of clauses, the same principles of debate apply, but the scope of the subject matter of the bill may be so wide that definition of relevancy is very difficult. However, debate should still conform to the rules for second reading debates and be relevant to the objectives and scope of the bill. Reference may be had to the second reading speech and the explanatory memorandum to help determine the objectives and scope of a bill. General discussion of a matter in a principal Act which is not referred to in the amending bill being debated has been prevented.[152]

Questions during second reading debate

In September 2010 the House adopted, as a trial, a longstanding Procedure Committee recommendation designed to encourage interactivity in debate.[153] The sessional order provided that, at the end of each Member’s speech during the second reading debate of a government bill, the Member could be questioned by other Members in relation to his or her speech. The Member was not obliged to take questions, and could indicate this during his or her speech. After each speech, questions and answers could continue for up to five minutes. Each question could take up to 30 seconds and each reply up to two minutes. This provision did not apply to the Minister’s second reading speech and a Minister’s speech closing the debate or to the speech of the main opposition speaker.

Second reading amendment

An amendment to the question ‘That this bill be now read a second time’, known as a second reading amendment, may only take one of two forms—that is, a ‘6 months’ amendment (see page 371) or a ‘reasoned amendment’.[154]

A reasoned amendment enables a Member to place on record any special reasons for not agreeing to the second reading, or alternatively, for agreeing to a bill with qualifications without actually recording direct opposition to it. It is usually declaratory of some principle adverse to or differing from the principles, policy or provisions of the bill. It may express opinions as to any circumstances connected with the introduction or prosecution of the bill or it may seek further information in relation to the bill by committees or commissions, or the production of documents or other evidence.

Relevancy and content

The standing orders[155] specify rules governing the acceptability of reasoned amendments. An amendment must be relevant to the bill.[156] In relation to a bill with a restricted title, an amendment dealing with a matter not in the bill, nor within its title, may not be moved.[157] In relation to a bill with an unrestricted title, an amendment dealing with a matter not in the bill, but which is relevant to the principal Act or to the objects of the bill as stated in its title, may be moved even though the clauses have a limited purpose.

For example, the Apple and Pear Stabilization Amendment Bill (No. 2) 1977 had as a long title ‘A Bill for an Act to amend the Apple and Pear Stabilization Act 1971’ and the object of the bill was to extend financial support to exports of apples and pears made in the 1978 export season. The bill dealt with extension of time of support only, not with the level of the support.[158] A second reading amendment to the effect that the bill be withdrawn and redrafted to increase the level of support was in order as the level of support was provided in the principal Act.[159] Even though a bill may have a very broad title, an amendment must still be relevant to the subject matter of the bill.[160] Reference may be made to the Minister’s second reading speech and the explanatory memorandum to clarify the scope of the bill.

The case of the Commonwealth Electoral Bill 1966 provides a good example of acceptable and unacceptable second reading amendments. The long title was ‘A Bill for an Act to make provision for Voting at Parliamentary Elections by Persons under the age of Twenty-one years who are, or have been, on special service outside Australia as Members of the Defence Force’. A second reading amendment was moved to the effect that, while not opposing the passage of the bill, the House was of the opinion that the vote should be given to all persons in the ‘call-up’ age group. The amendment was ruled out of order by the Speaker as the broad subject of the bill related to voting provisions for members of the defence forces under 21 years, whereas the proposed amendment, relating to all persons in the ‘call-up’ age group regardless of whether or not they were members of the defence forces, was too far removed from the subject of the bill as defined by the long title to be permissible under the standing orders and practice of the House. Dissent from the ruling was moved and negatived.[161] Another Member then moved an amendment to the effect that, while not opposing the passage of the bill, the House was of the opinion that the vote should be given to all persons in the Defence Force who had attained the age of 18 years.[162] This amendment was permissible as the practice of the House is to allow a reasoned amendment relevant to the broad subject of the bill.

Length

Although there have been some excessively long second reading amendments,[163] these are not welcomed by the Chair. Speaker Halverson ruled[164] that a second reading amendment should not be accepted by the Chair if, when considered in the context of the bill, and with regard to the convenience of other Members, it could be regarded as of undue length, and that it was not in order for a Member to seek effectively to extend the length of his or her speech by moving a lengthy amendment, without reading it, but relying on the fact that the amendment would be printed in Hansard. The Chair has directed a Member to read out a lengthy second reading amendment in full and for the time taken to do so to be incorporated into the time allocated for his speech, giving as the reason that the amendment was larger than that which would normally be accommodated and that he did not want lengthy amendments to become the norm.[165] The incorporation of an extensive quotation in a second reading amendment is not allowed.[166]

Anticipation of detail stage amendment

A reasoned amendment may not anticipate an amendment which may be moved during consideration in detail.[167] Following a Member’s explanation that an amendment had been drafted not with reference to the clause but with reference to the principle of the bill, an amendment which could possibly have been moved in committee (i.e. the former consideration in detail stage) was allowed to be moved to the motion for the second reading.[168] The principle underlying an amendment which a Member may not move during consideration in detail can be declared by means of a reasoned amendment. A second reading amendment to add to the question an instruction to the former committee of the whole was ruled out of order on the ground that the bill had not yet been read a second time.[169]

Addition of words

A reasoned amendment may not propose the addition of words to the question ‘That this bill be now read a second time’.[170] The addition of words must, by implication, attach conditions to the second reading.[171]

Direct negative

In addition to the rules in the standing orders governing the contents of reasoned amendments, it is the practice of the House that an amendment which amounts to no more than a direct negation of the principle of a bill is not in order.

Form of amendment

The usual form of a reasoned amendment is to move ‘That all words after ‘‘That’’ be omitted with a view to substituting the following words:…’ Examples of words used are:

- the bill be withdrawn and redrafted to provide for…

- the bill be withdrawn and a select committee be appointed to inquire into…

- the House declines to give the bill a second reading as it is of the opinion that…

- the House disapproves of the inequitable and disproportionate charges imposed by the bill…

- the House is of the opinion that the bill should not be proceeded with until…

- the House is of the opinion that the…Agreement should be amended to provide…

- whilst welcoming the measure of relief provided by the bill, the House is of the opinion that…

- the House notes with approval that, in response to public pressure, the Government has introduced this limited bill, but deplores…

- whilst not opposing the provisions of the bill, the House is of the opinion that…

- whilst not declining to give the bill a second reading, the House is of the opinion that…

Moving of amendment

A second reading amendment is usually moved by the relevant shadow minister during his or her speech at the start of the debate, but may be moved by any Member and at any time during the debate. By convention, if the Member has allowed sufficient time, copies of the terms of the amendment are circulated in the Chamber. If copies have been circulated, a Member may move an amendment by saying ‘I move the amendment circulated in my name’, instead of reading the terms out in full.[172] The fact that the moving of a reasoned amendment permits Members who have already spoken to the second reading to speak again to the amendment may influence the use or timing of the procedure.

Following the suspension of standing orders to enable a number of bills to be considered together and one question to be put on any amendments moved to motions for the second readings,[173] second reading amendments have been moved to six bills in one motion.[174]

Seconding

Immediately the Member moving the second reading amendment has finished his or her speech (not during the speech), the Speaker calls for a seconder. If the amendment is not seconded, there may be no debate on the amendment and it is not recorded in the Votes and Proceedings.[175] A copy of the amendment signed by the mover and seconder is handed to the Clerk at the Table.

Debate and questions put

When seconded, the Speaker states that ‘The original question was ‘‘That this bill be now read a second time’’, to which the honourable Member for…has moved, as an amendment, that all words after “That’’ be omitted with a view to substituting other words’. The Speaker then proposes the immediate question, traditionally in the form ‘That the words proposed to be omitted stand part of the question’, but from June 2011 in the form ‘That the amendment be agreed to’.[176] The question is open to debate.

A Member who moves an amendment, or a Member who speaks following the moving of an amendment, is deemed to be speaking to both the original question and the amendment. A Member who has spoken to the original question prior to the moving of an amendment may again be heard, but shall confine his or her remarks to the amendment. A Member who has spoken to the original question may not second an amendment subsequently moved. A Member who has already spoken in the second reading debate can only move a second reading amendment by leave of the House.[177]

The time limits for speeches in the debate are 15 minutes for a Member speaking to the motion for the second reading or to the motion and the amendment, including a Minister or Parliamentary Secretary speaking in reply. A limit of 15 minutes also applies for a Member who has spoken to the motion and is addressing the amendment.[178]

A Member may amend his or her amendment after it is proposed with the leave of the House (for example, to correct an error in the words proposed to be substituted).[179] A Member has been given leave to add words to an amendment moved by a colleague at an earlier sitting.[180] An amendment may be withdrawn only by leave.[181]

When the question has been proposed in the form ‘That the amendment be agreed to’, a motion to amend the proposed amendment may be moved. If the question in that form has been put and the amendment disposed of, a further second reading amendment may be moved.

If the debate has been closed by the mover of the motion for the second reading speaking in reply before the question was put on the amendment, the question on the second reading is then put immediately.[182] In other cases debate may continue on the motion for the second reading.[183]

Effect of question being put in the form ‘words omitted stand’

No amendment can be moved to the words proposed to be inserted or added until the question ‘that the words proposed to be omitted stand part of the question’ has been determined.[184]

If the question ‘That the words proposed to be omitted stand part of the question’ is resolved in the affirmative, the amendment is disposed of.[185] If the question ‘That the words proposed to be omitted stand part of the question’ were to be negatived, another question would be put ‘That the words proposed [the words of the amendment] be inserted’.[186] If this question was agreed to, a final question ‘That the motion, as amended, be agreed to’ would then be put.[187]

When the House has agreed that the original words of the motion should stand, no further second reading amendment is possible. The general rule that an amendment which adds other words may be moved to words which the House has resolved shall stand part of a question[188] does not apply in the case of a second reading amendment, which must not propose the addition of words to the question.[189]

When the question was routinely put in the traditional ‘words stand’ form, the alternative form ‘That the amendment be agreed to’ was proposed in special circumstances to allow the possibility of a further amendment after the first had been disposed of.[190]

See also ‘Putting question on amendment’ in the Chapter on ‘Motions’.

Effect of agreeing to reasoned amendment

As the House has never agreed to a reasoned amendment, it has no precedent of its own to follow in such circumstances. Although it seems unlikely, if a reasoned amendment were carried, that any further progress would be made, it could be argued that the amendment would not necessarily arrest the progress of the bill, as procedural action could be taken to restore the bill to the Notice Paper and have the second reading moved on another occasion.

This view was taken by the Chair during consideration of the Family Law Bill 1974, on which a free vote was to take place, when the effects of the carriage of an amendment expressing qualified agreement were canvassed in the House.[191] The amendment proposed to substitute words to the effect that, whilst not declining to give the bill a second reading, the House was of the opinion that the bill should give expression to certain principles.[192]

On that occasion a contingent notice of motion was given by a Minister that on any amendment to the motion for the second reading being agreed to, he would move that so much of the standing orders be suspended as would prevent a Minister moving that the second reading of the bill be made an order of the day for a later hour that day.[193] Subsequently the Chair expressed the view that the contingent notice would enable the second reading to be reinstated. If the contingent notice was called on and agreed to, the second reading of the bill would be made an order of the day for a later hour of the day. It would then be up to the House as to when the order would be considered (perhaps immediately). If the motion ‘That this bill be now read a second time’ were to proceed, it would be a completely new motion for that purpose and open to debate in the same manner as the motion for the second reading then before the House.[194]

Any determination of the effect of the carrying of a second reading amendment in the future may well depend upon the wording of the amendment. If the rejection is definite and uncompromising, the bill may be regarded as having been defeated.[195] However wording giving qualified agreement could be construed to mean that the second reading may be moved on another occasion.

On the other hand it could be argued that the House may be better advised to follow the practice that, after a reasoned amendment of any kind has been carried, no order is made for a second reading on a future day. This would be consistent with the practice in cases of the second reading being negatived. This is the modern practice in the UK House of Commons.[196] However, in the House of Commons reasoned amendments record reasons for not agreeing to the second reading and amendments agreeing to the second reading with qualifications are not the practice.[197]

Reasoned amendment in the Federation Chamber

The view has been taken that an unresolved question on a second reading amendment prevents further consideration of a bill in the Federation Chamber.[198]

‘6 months’ amendment

A ‘6 months’ amendment[199] is in the form ‘That the word ‘‘now’’ be omitted from, and the words “this day 6 months” be added to the question’.[200] No amendment may be moved to this amendment. If the amendment is defeated the question on the second reading is then restated. Debate may then continue on the motion for the second reading. The acceptance by the House of such an amendment would mean that the bill has been finally disposed of.[201] This form of amendment is rarely used as, from a debating and political viewpoint, it suffers by comparison with a reasoned amendment. On the last occasion it was moved on the motion for the second reading, the mover proposed to add ‘this day six months in order that the Government may confer…’.[202] Although the amendment was permitted by the Chair, the inclusion of the additional words was strictly out of order. It is now so long since this procedure has been used that it could, especially in its current wording, perhaps be regarded as obsolete.

Determination of question for second reading

When debate on the motion for the second reading has concluded, and any amendment has been disposed of, the House determines the question on the second reading ‘That this bill be now read a second time’. On this question being agreed to, the Clerk reads the long title of the bill.

Only one government bill has been negatived at the second reading stage in the House of Representatives,[203] but there have been a number of cases in respect of private Members’ bills.[204] The accepted practice of the House has been that in cases where the second reading has been negatived, the motion for the second reading has not been moved again.

The modern practice of the UK House of Commons is that defeat on second reading is fatal to a bill.[205] In the Senate rejection of the motion that a bill be read a second time does not prevent the Senate from being asked subsequently to grant the bill a second reading.[206]

Bill reintroduced

Should the Government wish to proceed further with a bill, the second reading of which has been negatived or subjected to a successful amendment, an appropriate course to take would be to have the bill redrafted in such a way and to such an extent that it becomes a different bill including, for example, a different long title. Alternatively, standing orders could be suspended to enable the same bill to be reintroduced, but this might be considered a less desirable course. See also ‘The application of the same motion rule to bills’ at page 357.

Bill not proceeded with

From time to time a bill will be introduced and remain on the Notice Paper until the reactions of the public to the proposal are able to be made known to the Government and Members generally. As a result of these representations, following an advisory report on the bill from a committee, or for some other reason,[207] the Government may wish to alter the bill substantially from its introduced form. This may not always be possible because the proposed amendments may not be within the title of the bill or relevant to the subject matter of the bill and may therefore be inadmissible under the standing orders.[208] In this case, and sometimes in the case where extensive amendments would be involved, a new version of the bill may be introduced. If this is done, the Government either allows the order of the day in respect of the superseded bill to remain on the Notice Paper until it lapses on dissolution or prorogation, or a Minister or Parliamentary Secretary moves for the discharge of the order of the day.[209] The new version of the bill is proceeded with notwithstanding the existence or fate of a previous similar bill. Discharge of a bill may occur before the presentation of the second version,[210] or after the second version has passed the House.[211]

Proceedings following second reading

Immediately after the second reading of a bill has been agreed to, standing order 147 requires the Speaker to announce any message from the Governor-General in accordance with section 56 of the Constitution recommending an appropriation in connection with the bill. This requirement applies to special appropriation bills only and is covered in the Chapter on ‘Financial legislation’.

Former standing orders provided for the possible referral of a bill to a select committee at this stage, but no bills were so referred. There was also provision for the moving of an instruction to a committee—very few instructions were ever moved and only one agreed to (probably unnecessarily). These obsolete provisions are discussed in previous editions.

Reference to legislation committee

Thirteen bills were considered by legislation committees pursuant to sessional orders operating from August 1978. Sessional orders were also adopted in March 1981 for the 32nd Parliament;[212] however, no bills were referred. The sessional orders provided that, immediately after the second reading or immediately after proceedings following the second reading had been disposed of, the House could (by motion on notice carried without dissentient voice) refer any bill, excluding an appropriation or supply bill, to a legislation committee (in effect, for its consideration in detail stage).[213]

Leave to move third reading/report stage immediately

The standing orders provide that, at this stage, the House may dispense with the consideration of the bill in detail and proceed immediately to the third reading.[214] If the Speaker thinks Members do not desire to debate the bill in detail, he or she asks if it is the wish of the House to proceed to the third reading immediately. If there is no dissentient voice, the detail stage is superseded and the Minister moves the third reading immediately. One dissentient voice is sufficient for the bill to be considered in detail. For a bill referred to the Federation Chamber the equivalent bypassing of the detail stage is achieved by the granting of leave for the question ‘That the bill be reported to the House without amendment’ to be put immediately.[215]

The detail stage is bypassed in the consideration of approximately 75% of bills.

Former committee of the whole

The words ‘committee stage’ found in earlier publications about the procedures of the House, and also in descriptions of the practice of the Senate and other legislatures, refer to what the House now knows as the ‘detail stage’ (described below).