CHAPTER 6

Wages, conditions, safety and entitlements of 457 visa holders

Introduction

6.1

One of the recurring themes of this inquiry has been the exploitation of

temporary visa workers. The next three chapters examine the wages, conditions,

safety and entitlements of three sets of temporary visa workers. This chapter

has a particular focus on 457 visa workers; chapter 7 focusses on Working

Holiday Maker (WHM) visa holders; and chapter 8 focusses on international

student visa holders.

6.2

The chapter begins with an examination of the underlying structural

factors that render temporary visa workers vulnerable to exploitation. It then considers,

in general terms, whether temporary visa programs 'carve out' groups of

employees from Australian labour and safety laws and, if so, to what extent

this threatens the integrity of such laws. This is followed by a section that

looks at the challenges and barriers that 457 visa workers face in seeking

access to justice and a remedy for exploitation.

6.3

There are two case studies of the exploitation of 457 visa workers: one

in the construction industry, and one in the nursing sector. The chapter concludes

with the committee's views on these matters.

Vulnerability of temporary migrant workers

6.4

One of the key debates surrounding the exploitation of temporary visa

workers is not just the extent to which it occurs, but the reasons for it.

While some submitters blamed a few rogue employers for the problem, the

committee received a substantial body of evidence to indicate that there are

underlying structural factors that contribute to the vulnerability of temporary

visa workers to exploitation.

6.5

Associate Professor Joo-Cheong Tham argued that widespread noncompliance

with workplace laws is best explained by 'the interaction of precarious migrant

status with the dynamics of poorly regulated labour markets; labour markets

where precarious migrant status can become the currency for noncompliance'.[1]

6.6

These dynamics are particularly apparent in the cleaning, taxi-driving

and hospitality industries which are, according to Associate Professor Tham, governed

by 'precarious work norms' including poor working conditions and the frequent breach

of labour laws.[2]

6.7

Associate Professor Tham therefore disagreed with the proposition that noncompliance

with labour laws was an aberration that could be attributed to a few rogue

employers'.[3]

Instead he argued that the vulnerability of temporary migrant workers arises

from a series of over-lapping structural factors that contribute to the

precarious nature of their status, including:

-

dependence on a third party for the right of residence;

-

limited right of residence;

-

limited authority to work; and

-

limited access to public goods.[4]

Dependence on a third party

6.8

Several submitters and witnesses stated that the high level of

dependence on the sponsoring employers (which is built into the design of the

457 visa program) is the main factor that determines the vulnerability of 457

visa workers to non-compliance with workplace laws.[5]

6.9

JobWatch, an independent, not-for-profit employment rights community

legal centre was established in 1980 and is based in Melbourne. JobWatch

pointed out that the inherent power imbalance in the employment relationship is

ameliorated to some extent by employee entitlements and protections in the Fair

Work Act 2009 (FW Act). However, the dependence of the 457 visa worker on the

sponsoring employer had the effect of exacerbating the power imbalance between

employer and employee.[6]

A similar view was expressed by Ms Jessica Smith, a senior solicitor at the Employment

Law Centre of Western Australia (Employment Law Centre of WA).[7]

6.10

This view of vulnerability has historical precedent. In 2008, the Deegan

review drew attention to the unique status of temporary visa workers in the

Australian workplace:

Despite the views of some employers and employer

organisations, Subclass 457 visa holders are different from other employees in

Australian workplaces. They are the only group of employees whose ability to

remain in Australia is largely dependent upon their employment, and to a large

extent, their employer. It is for these reasons that visa holders of this type

are vulnerable and are open to exploitation.[8]

6.11

Importantly, the Deegan review also found:

If these employees are visible and their treatment is open to

scrutiny then exploitation is less likely to occur. The more invisible the visa

holder, the more opportunity there is for exploitation.[9]

6.12

The visibility of temporary visa workers is covered in greater depth in

chapter 8 in the section on the particular vulnerability of undocumented

workers.

6.13

The lack of freedom to choose an employer led the Australian Council of

Trade Unions (ACTU) to express concern about the increased vulnerability of 457

visa workers:

At the individual level, employer-sponsored visas where

workers are dependent on their employer for their ongoing visa status increase

the risk for exploitation as workers are less prepared to speak out if they are

underpaid, denied their entitlements, or otherwise treated poorly.[10]

6.14

The Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) concurred, arguing that dependence

on an employer provided 'a strong disincentive for an employee to stand up for

their rights' and an equally 'strong incentive for unscrupulous employers to

'lord it over' employees'.[11]

6.15

The MUA was therefore of the view that the dependence of a 457 visa

worker on their employer rendered the 457 visa program an inappropriate 'policy

tool to balance the protection of employees rights and entitlements with the capacity

of the Australian economy to meet skills shortages'. Consequently, the MUA

recommended that a visa holder's right to remain in Australia should not be

contingent upon the visa holder remaining employed by the same employer.[12]

6.16

Dependence also occurs when temporary visa workers are offered a

contract of employment in their country of origin, but on arrival in Australia,

the workers are presented with a new contract. The need to remain in Australia because of the debt incurred renders migrant

workers vulnerable to this type of exploitation and means they have 'no choice

but to accept those conditions'.[13]

6.17

The committee heard that the nexus between engagement by the sponsoring employer

and the ability to remain in Australia creates a fear amongst visa workers that

they will be sent home to their country of origin if they complain and

therefore 'also explains why 457 visa workers are reluctant to complain of

ill-treatment or illegal conduct'.[14]

6.18

Dr Joanna Howe pointed out that this level of structural dependence

would be exacerbated for Chinese workers brought to Australia by Chinese

employers under the Chinese Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA):

And the biggest point is that their migration status is

linked to their employment status, so under the IFA, unlike any of the other

visa arrangements we have, an employer will be able to fly in Chinese workers

and their right to stay in Australia will be contingent upon their employer agreeing.

That worker is extremely vulnerable because if they complain they will get sent

back home, and they know that, and the huge income disparities between China

and Australia mean this worker knows that even if he or she is being paid below

the minimum, even if he is living in cramped accommodation, even if he is being

treated poorly, he is still getting a higher wage than in China. The fact that

migration status is linked to employment status basically creates the

structural conditions for this worker to be exploited.[15]

Limited right of residence

6.19

Dependence on an employer not only for work but, ultimately, the right

to stay in the country, has left some 457 visa workers vulnerable to

exploitative conditions. This dependence is exacerbated in cases where a

temporary visa holder is either seeking to extend their stay in the country

(for example, in the case of a WHM visa holder seeking to qualify for a second

year visa), or, in the case of a 457 visa holder, seeking to use the 457 visa

as a pathway to permanent residence.[16]

6.20

The ACTU stated that trying to progress from a temporary 457 visa to a

permanent employer-sponsored visa creates problems because:

...temporary overseas workers with the goal of

employer-sponsored permanent residency have their future prospects tied to a

single employer. Under visa rule changes effective from 1 July 2012, 457 visa

workers must stay with their 457 sponsor for a minimum period of 2 years before

becoming eligible for an employer-sponsored permanent residency visa with that

employer.

Again, this makes them much more susceptible to exploitation

and far less prepared to report problems of poor treatment in the workplace for

fear of jeopardising that goal.[17]

6.21

This view has historical precedent with the Deegan review receiving evidence

that:

...where a visa holder has permanent residency as a goal that

person may endure, without complaint, substandard living conditions, illegal or

unfair deductions from wages, and other similar forms of exploitation in order

not to jeopardise the goal of permanent residency.[18]

Limited authority to work

6.22

The limited authority of a 457 visa worker to work means, in practice,

that a 457 visa worker can be even more vulnerable if they are employed in

violation of workplace laws:

It is a cruel irony that if a 457 visa worker is engaged by

an employer in violation of labour laws, this can, in fact, strengthen the hand

of the employer. For instance, a 457 visa worker who works in a job

classification different (most likely lower) from that stated in his or her

visa would be in breach of Visa Condition 8107. Not only would the visa be

liable to cancellation in this scenario, but the worker would also be

committing a criminal offence. Even when a violation of labour laws does not

involve a breach of the worker's visa, there can still be a perception that the

worker's participation in illegal arrangements, if disclosed, might jeopardise

the visa, or his or her prospect of permanent residence. In these

circumstances, continuing in illegal work arrangements might be seen as

preferable to the regularisation of status.[19]

6.23

Research from Dr Stephen Clibborn at the University of Sydney Business

School reinforced this perspective on the unique vulnerability of temporary

visa workers that are coerced into breaching their visa status by unscrupulous

employers precisely so the employer gains extra leverage over the worker in

order to exploit them.[20]

This particular aspect of the vulnerability of temporary visa workers is

covered in greater detail in chapter 8 in the section on undocumented migrant

workers.

Limited access to public goods

Fair Entitlements Guarantee

6.24

One of the key questions pertaining to any temporary visa program is the

extent to which the worker is eligible for the same entitlements as Australian

citizens and permanent residents.

6.25

Mr Peter Mares, Adjunct Fellow at the Institute for Social Research at

Swinburne University of Technology, drew the committee's attention to the Fair

Entitlements Guarantee (FEG). He noted that according to the Department of

Employment, the purpose of the FEG was to assist people 'owed certain

outstanding employee entitlements following the liquidation or bankruptcy of

employers'.[21]

6.26

Under the Fair Entitlement Guarantee Act 2012, a person must be an

Australian citizen or, under the Migration Act 1958, the holder of a

permanent visa or a special category visa[22]

in order to be eligible for payments. Mr Mares pointed out that the eligibility

criteria for the FEG necessarily disqualified temporary visa holders from

accessing government assistance 'when their employer goes bust owing them money'.[23]

6.27

Mr Mares cited the example of Swan Services Cleaning Group that went

into administration in May 2013, and which owed $2.3 million in unpaid wages

and $7.2 million in annual leave entitlements to around 2500 workers. Mr Mares

noted that:

A large proportion of the Swan Services workforce – about

half of its staff in Victoria – was made up of international students. Many

were left with up to three weeks' worth of unpaid wages and some were owed

close to $3000.[24]

6.28

Mr Mares therefore concluded that with respect to the FEG:

...the entitlements of temporary visa holders are inferior to

the conditions enjoyed by Australian citizens, permanent residents and New

Zealanders (Special Category Visa holders).[25]

Workers' compensation entitlements

6.29

The committee received evidence that posed questions around the workers'

compensation entitlements of temporary visa holders. The committee heard that

there is legal uncertainty about whether temporary visa workers would be treated

equally with Australian citizens or permanent residents if they suffered a

debilitating, life-long disability as a result of a workplace accident. Mr

Mares recommended that a legal audit of all workers rehabilitation and

compensation schemes should be undertaken with particular attention paid to

whether the entitlements of a temporary visa worker would be diminished or

restricted in any way if that worker were to cease residing in Australia.[26]

6.30

These matters are particularly relevant if a 457 visa worker were to

suffer a workplace injury that prevented them from working for a period of

three months or more. In these circumstances, if a 457 visa worker had to leave

the country for not meeting their sponsorship and employment obligations, they

might be ineligible for workers' compensation because they would be residing

overseas.

Free childhood immunisation

6.31

Universal free childhood vaccination in Australia is restricted to

citizens, permanent residents, and other people eligible to hold a Medicare

card. Mr Mares pointed to evidence from health authorities that indicated migrants

are at risk of having lower immunisation rates than the broader community and

that migrants may face additional barriers in accessing immunisation on the

basis of their temporary visa status.[27]

6.32

Although international students and 457 visa holders are required to

take out private health insurance that may rebate the cost of vaccinations (at

least up to the level of the standard Medicare rebate), Mr Mares pointed out

that 'this restriction may result in immunisations being postponed or not

carried out at all'.[28]

6.33

Mr Mares therefore proposed that universal free vaccination be extended

to encompass the babies and children of all temporary migrants regardless of

their temporary visa status.[29]

Universal free school education

6.34

The children of 457 visa holders in New South Wales (NSW), the Australian

Capital Territory (ACT) and Western Australia (WA) are required to pay international

fees to attend state schools. Mr Mares drew the committee's attention to the

fact that most government funded or subsidised services do not depend on the

visa status of the individual. He argued that, in a democratic country, the

children of temporary visa workers living in Australia should have the right to

access free childhood education in a state school.[30]

6.35

The committee also heard evidence at the hearing in Perth in July 2015

that the Western Australian government was looking to impose education fees of

$4000 on the families of 457 visa workers. Mr Dean Keating, Vice President of

Cairde Sinn Fein Australia stated that the announcement by the state government

had caused great concern amongst 457 visa workers to the extent that some had

re-considered their employment options. Mr Keating stated that the state

government did not appear to have consulted the business community over the

impacts of the proposal on those employers that sponsored and relied heavily on

457 visa workers.[31]

6.36

Eventus Corporate Migration group also noted that in some states 457

visa holders are required to pay school costs for school aged children. Eventus

pointed out that 'this can be prohibitive for many middle income earners,

particularly where multiple children are present in Australia'. Accordingly,

Eventus recommended that this issue be revisited.[32]

Access to justice

6.37

The committee received evidence from unions and community organisations to

indicate that even though temporary visa workers are covered by Australia's

workplace laws, they face greater difficulties in enforcing their workplace

rights and accessing justice than permanent residents and citizens. Mr Grant

Courtney, Branch Secretary of the Australasian Meat Industry Employees' Union

(Newcastle and Northern NSW) noted that visa workers only have a limited time

in Australia, and that by the time matters get to court, the visa worker 'is

generally back in their home country'.[33]

6.38

Both JobWatch and the Human Rights Council of Australia observed that

457 visa workers 'are extremely reluctant to seek recourse under workplace laws

for the apparent contravention by their employer of their employment rights'

because of fears about their visa status.[34]

6.39

Furthermore, 'migrant workers often have limited English language skills

and knowledge of and access to the legal system which can make asserting their

workplace rights even more difficult'.[35]

6.40

In addition, JobWatch pointed out that 'migration law does not guarantee

the residency status of a temporary migrant worker who is seeking to challenge

their dismissal or make another workplace claim in the context of their

employer's revocation of their sponsorship'.[36]

6.41

The combination of vulnerability, limited knowledge of workplace rights

and the legal system, and limited rights of residency, means that 'migrant

workers suffer lower levels of access to the rights that they technically hold

under law'.[37]

6.42

Mr Ian Scott, senior lawyer at JobWatch, noted that an unfair dismissal

claim at the Fair Work Commission could take six months to resolve. However, a general

protections claim (discrimination, workplace rights, union membership or

non-union-membership) under the FW Act in the Federal Court or the Federal

Circuit Court could run for up to 12 months or more.[38]

6.43

The committee heard that if a 457 visa worker was dismissed by their

employer, the remedy for unfair dismissal was complicated by the fact that

dismissal also entailed a termination of the 457 visa holders sponsorship

arrangements such that the 457 visa worker would need to either find another

sponsor or gain reinstatement with the original sponsor with 90 days, or face

removal from the country. The Employment Law Centre of WA therefore recommended

that the Fair Work Commission, the Federal Circuit Court and the Federal Court

be given 'the power to order the reinstatement of an employer's visa

sponsorship obligations in addition to the power to order the reinstatement of

the employee's employment'.[39]

6.44

JobWatch argued that if an employee had to leave the country because they

lost their visa status, this would cause 'an additional injustice in that they

can't practically enforce their rights'. Dr Laurie Berg, a member of the Human

Rights Council of Australia referred to this scenario as a 'cruel irony'.[40]

6.45

With respect to 457 visa workers, Jobwatch therefore proposed:

That temporary migrant workers who find themselves in a

position of losing their employer's sponsorship because they have been

dismissed, be entitled to an automatic bridging visa covering the period while

they are challenging their dismissal.[41]

6.46

The committee was concerned about the potential for automatic granting

of a bridging visa to be abused. Mr Scott reassured the committee that there

were sufficient provisions in the system to ensure against false and spurious

claims being mounted in order to rort the system:

The word 'automatic' is a strong word. Obviously checks and

balances should be involved. When the submission says 'automatic', I guess it

means that the rights apply for a bridging visa on the basis of a challenge to

a dismissal. For example, in unfair dismissal there are a lot of jurisdictional

issues. You have to tick all these boxes even to be eligible to apply, so you

could not really run a false claim; you would be kicked out by the Fair Work

Commission quite quickly. For other types of claim, where a claim is frivolous,

vexatious or lacking in substance, has no real prospect of success et cetera,

that party can be ordered to pay the other side's legal costs. So there are

already mitigating factors against running spurious claims in those

jurisdictions.

...

All those jurisdictions have the right for one party—in this

case the respondent employer—to apply to strike out that applicant's case if it

is lacking in substance.[42]

6.47

In cases of alleged unfair dismissal involving a 457 visa worker, the

worker has 90 days to find another employer sponsor. During this period, a 457

visa worker is not entitled to Centrelink benefits and must rely on friends,

community, and unions to survive. In many instances, however, community support

is complicated by the fact that workers are exploited by employers from the

same community. The committee heard that unions have assisted workers with

food, accommodation, cash donations, finding another job, and retrieving

underpaid wages and entitlements.[43]

6.48

Given the tight timeframes that apply to 457 visa workers seeking to

find another sponsor, the Employment Law Centre of WA recommended 'expedited

procedures in the relevant courts and tribunals specifically for temporary visa

holders':

That would mean that, for example, if they make an unfair

dismissal claim, that could be resolved relatively quickly, which would

increase the chances that it may even be resolved within that 90-day time

frame. That would also reduce the amount of time that temporary visa holders

would need a bridging visa to pursue those proceedings.[44]

6.49

Both the Employment Law Centre of WA Australia and JobWatch advised the

committee of reductions in government funding, which reduces the ability of

these organisations to provide legal advice on employment matters to temporary

visa holders. Both centres noted that it would be very difficult to continue

their work if the funding were not renewed.[45]

Exploitation of 457 visa workers

6.50

The extent of noncompliance with workplace laws relating to the

employment of 457 visa workers is difficult to determine precisely. Efforts to

determine the extent of noncompliance rely on the monitoring of sponsors by the

Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP), and also on reports to

unions and organisations such as Employment Law Centres.

6.51

It is important to note that the basis for the information provided by

the DIBP has changed over time. In the early years, the DIBP monitored almost

half of all 457 visa employers. Since 2009, however, the DIBP has adopted

a risk-tiering approach with a focus on 'high risk' sponsors.[46]

6.52

Associate Professor Tham noted that prior to 2009, there were several

instances of gross exploitation of 457 visa workers, but that the incidence of

such cases has decreased, probably as a result of the introduction of 'market

salary rates' and greater monitoring. To this extent, therefore, it could be

argued that effective regulation combined with active compliance monitoring has

reduced the structural risk of non-compliance.[47]

6.53

However, Associate Professor Tham sounded a note of caution because the

'aggregate data does tell the complete story'.[48]

For example, the Azarias review found significantly higher levels of

non-compliance relating to employers of 457 visa workers in particular

industries such as construction, hospitality and retail, and amongst small

businesses with nine or less employees.[49]

6.54

With respect to higher levels of non-compliance being more prevalent in

certain industries, Associate Professor Tham stated that the stronger risk of

non-compliance in the hospitality and construction industries arose from two

underlying structural factors:

-

the precarious migrant status of the workers; and

-

the labour market dynamics of those particular industries.[50]

6.55

JobWatch noted that it regularly receives calls from temporary visa

workers and that in 2014, 43 callers identified themselves as 457 visa holders.

JobWatch documented eight case studies from 457 visa holders identifying

several areas of concern:

-

underpayment and/or non-payment of entitlements;

-

unfair dismissal;

-

discrimination;

-

unreasonable requests of workers by employers;

-

work in contravention of visa conditions;

-

harassment of workers by employers;

-

threats of deportation; and

-

employers requiring payment for sponsorship.[51]

6.56

The Employment Law Centre of WA also provided a series of case studies

and associated outcomes involving a similar range of issues to those documented

by JobWatch.[52]

6.57

With the precarious status of 457 visa workers and the labour market

dynamics of certain industries as context, the next two sections present two

case studies of 457 visa worker exploitation: the first from the construction

industry, and the second from the nursing and aged care sector.

6.58

The committee notes, however, that the two case studies below are not

isolated instances. For example, the Electrical Trades Union (ETU) provided

evidence about the exploitation of a group of Filipino 457 visa workers in the power

industry previously employed by Thiess.[53]

6.59

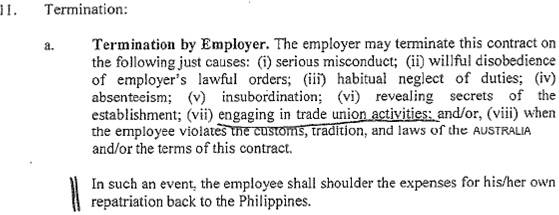

The ETU submitted a Thiess contract signed by the Executive General

Manager of Thiess Services Pty Ltd (see Figure 6.1 below). Clause 11(a)(vii) of

the contract stated that if a 457 visa worker engaged in trade union

activities, their contract could be terminated. As a consequence of termination,

the worker would need to return to the Philippines (with their family) at their

own expense.[54]

The committee notes that the inclusion of such a clause in a contract is illegal.

Figure 6.1: Thiess Services Pty Ltd, Master Employment

Contract

Source: Electrical Trades

Union, Submission 12, Additional information.

Case study—Construction: Chia Tung

6.60

The committee heard evidence from members of the Construction, Forestry,

Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) about the exploitation of 457 visa workers in

the construction industry, including the reasons why these workers are

unwilling to complain about their working and living conditions.

6.61

Mr Edwin De Castro, a Filipino 457 visa worker, worked as a welder and

metal fabricator for the Taiwanese company, Chia Tung Development, constructing

a feed mill in Narrabri. He was recruited by a labour hire company in the

Philippines. Once in Australia, Mr De Castro was required to work ten hours a

day for six or seven days a week over a two month period at Narrabri. [55]

6.62

Mr De Castro also stated that the working conditions were unsafe:

They forced us to work unsafely because they never provided

proper scaffoldings. We used an old harness. We did not have the right to

refuse, although we knew it was unsafe.[56]

6.63

Furthermore, the accommodation was substandard, overcrowded, and

expensive:

...we were six in one bedroom and another in a shipping

container—while they were deducting $250 each week for each of us for our

accommodation.[57]

6.64

Mr De Castro explained that Chia Tung 'never provided pay slips' and

that his salary was remitted in United States (US) dollars from Taiwan to his

bank account in the Philippines. Although a food allowance was in the hiring

agreement, Mr De Castro stated that Chia Tung did not provide a food allowance.[58]

6.65

Mr De Castro also recounted the circumstances in which Chia Tung

dismissed the 457 visa workers without notice and evicted them from their

accommodation:

During the night they forced us to leave the premises,

because we were living on the site. The police said that our contract had been

terminated. They did not give any notice to us or inform us. They forced us to

leave the premises, otherwise they said they would charge us with trespassing.

So we moved to a motel that night. They were planning to ship us out of the

country to avoid any troubles, but it was stopped by the union.[59]

6.66

Mr De Castro explained that the CFMEU prevented the workers from being

deported and found them new jobs:

The CFMEU secretary and organiser Dave Curtain helped us.

They feed us and paid for everything—our stay in the motel in Narrabri for more

than a week. They brought us here to Sydney and found us new jobs. We are very

lucky that we have one now.[60]

6.67

Chia Tung grossly underpaid the visa workers. According to Mr David

Curtain, a CFMEU organiser, the CFMEU has recovered $883 000 for 38 workers

who had been employed for between six weeks and four months. Mr Curtain also

noted that once the superannuation to which the workers were entitled was paid,

the final figure for the underpayments would be in excess of $1 million.[61]

6.68

Mr Curtain advised the committee that this sort of exploitation was

widespread in the construction industry. He recounted a similar example from

Bomaderry where 16 Filipino and 13 Chinese nationals were suffering similar

exploitation including overwork, underpayment, safety concerns, and 'atrocious'

living conditions.[62]

6.69

Mr Curtain also explained why migrant workers are unwilling to complain.

The reasons include a justifiable fear of being sacked and deported, and also a

fear of what might happen to their families back in their home countries:

They were being bullied. They had a foreman down there who

had come out on, I think, a 600 class visa. It was well known that his family

was involved in the Filipino military. The guys down there understood it and

they had expressed to us that they had grave concerns that, if they spoke out

and caused trouble, there might very well be trouble back home for their

families.[63]

Case study: Nursing

6.70

The committee heard evidence from the Australian Nursing and Midwifery

Federation (ANMF) about the exploitation of 457 visa workers in the nursing

industry, including the improper charging of visa application fees and the

underpayment of wages amounting to many tens of thousands of dollars. The

committee notes that only 457 workers were underpaid, and that Australian

workers were paid properly.

6.71

Mrs Dely Alferaz applied through an agent overseas for a 457 visa. She came

to Australia on a student visa to do a three-month bridging course to upgrade

her pre-existing nursing qualification and subsequently worked in an aged-care

facility in Victoria on a 457 visa. She is now a registered nurse.[64]

6.72

Although the 457 visa sponsor (the employer) paid the nomination fee,

the employer subsequently deducted payments from Mrs Alferaz's fortnightly

wages as a means of recouping the sponsorship fee of between $2000 and $3000. Mrs

Alferaz stated that three other migrant workers in another facility run by the

same employer were also being charged for the sponsorship fee. Similarly, Mr

Reni Ferreras, another registered nurse, was asked by the same employer to pay

between $3000 and $3500 for his 457 visa. The charges were listed as 'visa

deductions' on his payslip.[65]

6.73

According to the ANMF, the fee is a cost incurred by the sponsoring

employer and the applicant is not liable for the charges under the terms of the

457 visa program. Mrs Alferaz stated that she did not complain about the

deductions made by the employer because she was unaware that the employer

should not be charging her. Likewise, Mr Ferreras said the visa and migration

agent fees were not explained properly and that he was not given any choice in

the matter: he would simply have to pay the fees if he wanted to be sponsored

for a 457 visa.[66]

6.74

The lack of understanding amongst 457 visa workers about the

responsibility for the payment of visa fees also extends to the correct pay

rates for certain types of work. The consequence is that migrant nurses have

been underpaid for their work.

6.75

Mrs Alferaz looked after 50 residents on her own and was in charge of

the facility. Under the enterprise bargaining agreement, Mrs Alferaz should

have been paid at the grade 4 rate since 2009. However, Mrs Alferaz had not

been paid at the correct rate and consequently was owed $57 000 in

underpaid wages.[67]

6.76

Mr Nicholas Blake, the Senior Industrial Officer with the ANMF, stated

that four or five 457 visa workers had been underpaid across the two facilities

run by the same employer, with all the workers being owed approximately the

same amount. For example, Mr Reni Ferreras, another registered nurse, stated that

the ANMF had calculated that he was owed approximately $60 000 in

underpayments.[68]

6.77

The underpayments included being paid the incorrect rate as well as not

receiving any payment whatsoever (neither ordinary or overtime rates) for

overtime hours worked. Mr Blake stated there were rosters and payslips to back

up the claims and that the Victorian branch of the ANMF was handling the

matter.[69]

6.78

Ms Annie Butler, Assistant National Secretary of the ANMF, pointed out that

the vulnerability of migrant workers tended to prevent them coming forward with

complaints. However, based on anecdotal evidence, the ANMF believed improper visa

fee charges and the underpayment of wages were widespread.[70]

6.79

The evidence from the ANMF pointed to a relationship between the

employer and the migration agent where the employer directed the 457 visa

workers to use a particular migration agent who charged a large fee for the permanent

residency application. Ms Angela Chan, National President of the Migration

Institute of Australia, advised that all cases of potential malpractice involving

a migration agent should be referred to the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) for

investigation. Noting there are unregistered migration agents both in Australia

and overseas, Ms Chan stressed that it was important for both visa applicants

and employers to check that a migration agent is registered through the

Migration Agents Registration Authority.[71]

Committee view

6.80

Evidence to the inquiry indicated that the high level of regulation of both

the 457 visa program and the Seasonal Worker program is an important factor in

helping prevent and reduce exploitation. The 457 visa program regulates minimum

salary levels, is subject to an increasing amount of compliance monitoring, and

457 visa workers are generally located in higher skilled occupations.

6.81

Nevertheless, 457 visa workers are still vulnerable to exploitation. One

of the key factors leading to the potential for exploitation is the structural dependence

of the 457 visa worker on their sponsoring employer. This dependence was so

extreme in the case of 457 visa workers employed by Thiess that Thiess felt

emboldened to threaten its visa workers by inserting an illegal clause into the

employment contract stating that if a 457 visa worker engaged with a trade

union, then that would be sufficient grounds for terminating their employment.

6.82

Claims that only 'rogue' employers are doing the 'wrong thing' and that

'most employers are doing the right thing' are hard to substantiate because the

actual extent of non-compliance with Australian labour laws is difficult to

verify. While the committee acknowledges that the number of 457 visa workers

being exploited may be low compared to the Working Holiday Maker (WHM) and

international student visa programs, the committee received evidence of higher levels

of exploitation of 457 visa holders in certain industry sectors including

construction and nursing. (The higher incidence of exploitation of

international student visa holders in retail is covered in chapter 8).

6.83

Furthermore, the quantum of underpayment involving 457 visa workers can

be substantial. This is clear, not only from the evidence presented in this

chapter, but also from the statistics published by the FWO.

6.84

The recommendations in chapter 9 around compliance monitoring have

relevance to the issue of the exploitation of 457 visa workers. However, given

that systemic factors contribute to the special vulnerability of temporary

migrant workers, it is pertinent to consider those structural factors that

could be addressed in order to alleviate the precariousness of temporary

migrant work.

6.85

The ability of temporary visa workers to access the FEG was considered

by the Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee inquiry into the

framework and operation of subclass 457 visas, Enterprise Migration Agreements

and Regional Migration Agreements. That report found the omission of 457 visa

workers from the FEG to be, 'on its face, discriminatory, given that there is

no coherent policy basis justifying the distinction between the entitlements of

local and 457 visa workers in such circumstances'. That report therefore recommended

that the Fair Entitlement Guarantee Act 2012 (FEG Act) be amended to make

temporary visa holders eligible for entitlements under the FEG.

6.86

This inquiry had wider terms of reference than the Senate Legal and

Constitutional References Committee inquiry in that it was directed to look at all

temporary visa holders. The committee received evidence that many WHM and international

student visa holders effectively work full-time and that, in one case, a large

number of international students were owed thousands of dollars when their

employer went broke.

6.87

In a situation where an the employer goes into receivership with unpaid

liabilities to its staff, Australian citizens, permanent residents and New

Zealanders (Special Category Visa Holders) can access payments under the Fair

Entitlement Guarantee. But temporary visa workers are currently ineligible to

access the Fair Entitlement Guarantee. The committee concurs with the position

of the Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee report on this

matter and, accordingly, is of the view that under principles of fairness and

equal treatment, this situation should be rectified so that temporary visa

workers are afforded the same protection as Australian workers.

6.88

Evidence to the committee pointed to uncertainty around the entitlements

of temporary visa workers to workers compensation in the event of a severe

workplace injury. The committee notes that many temporary visa holders have

contributed to Australian society and its economy over many years. However,

certain provisions within various workers' compensation schemes may effectively

'carve out' temporary visa workers, particularly if the visa worker has to

return to their home country.

6.89

As a first step, these matters require urgent clarification. The

committee therefore recommends an audit of all workers rehabilitation and

compensation schemes to determine whether temporary migrant workers who suffer

a debilitating, life-long disability as the result of a workplace accident

would be treated equally with Australian citizens or permanent residents in

similar circumstances. Noting that workers' compensation schemes are presided

over by a range of different jurisdictional authorities, the committee proposes

a review of workers' compensation legislation with a view to determining the

feasibility of correcting any deficiencies in the relevant legislation such

that temporary visa workers are treated equally with Australian workers in

similar circumstances.

6.90

In terms of broader public policy measures, evidence to the inquiry

indicated that migrants are at risk of having lower immunisation rates than the

broader community and that migrants may face additional barriers in accessing

immunisation on the basis of their temporary visa status. The committee is of

the view that sensible public policy dictates the removal of unnecessary

barriers to the implementation of universal childhood vaccination. In order to

facilitate this goal, the committee is of the view that universal free

vaccination should be extended to the babies and children of all temporary visa

holders living in Australia, regardless of their visa status.

6.91

Access to justice under the law is a fundamental principle of a liberal

democracy. Yet a body of evidence to the committee found that temporary visa

workers face greater difficulties in enforcing their workplace rights and

accessing justice than permanent residents and citizens. This is due in large

part to a fear that their visa status and, with it, any hopes of progressing

through the system towards permanent residency, may be compromised if a

temporary visa worker registers a complaint against their employer.

6.92

While a combination of vulnerability and limited knowledge of workplace

rights and the legal system are at play here, the limited rights of residency is

the key factor that effectively undercuts a temporary visa worker's access to pursue

a legal remedy. In this regard, the committee concurs with the finding of the 2013

Senate Legal and Constitutional References Committee report that:

...the substantive impairment of 457 visa holders in respect of

seeking effective remedies or maintaining entitlements under workplace and occupational

health and safety laws undermines one of the clear policy aims of the 457 visa

program, namely that 457 visa holders receive no less favourable conditions than

local workers.

6.93

The committee is therefore of the view that, where required, access to a

bridging visa to pursue a meritorious workplace claim is a necessary part of

ensuring that temporary visa workers enjoy the same access to justice that an

Australian worker would in similar circumstances.

6.94

In this regard, the committee is persuaded that sufficient provisions

already exist within the system to prevent abuse of such a temporary bridging

visa with the pursuit of false or spurious claims. As per the Senate Legal and

Constitutional References Committee report, the committee notes that, in

addition to amendment and harmonisation of relevant Commonwealth and state and

territory legislation and schemes, addressing this substantive impairment of

457 visa workers' rights may also require changes to the immigration program to

provide adequate bridging arrangements to allow 457 visa workers to pursue

meritorious claims under workplace and occupational health and safety

legislation.

Recommendation 18

6.95

The committee recommends that the Fair Entitlements Guarantee Act

2012 be amended to make temporary visa holders eligible for entitlements

under the Fair Entitlements Guarantee.

Recommendation 19

6.96

The committee recommends that the immigration program be reviewed and,

if necessary, amended to provide adequate bridging arrangements for all

temporary visa holders to pursue meritorious claims under workplace and

occupational health and safety legislation.

Recommendation 20

6.97

The committee recommends an audit of all workers rehabilitation and

compensation schemes to determine whether temporary migrant workers who suffer

a debilitating, life-long disability as the result of a workplace accident

would be treated equally with Australian citizens or permanent residents in

similar circumstances. The audit should also determine if a temporary migrant

worker's entitlements would be diminished or restricted in any way if that

worker were no longer to reside in Australia. Subject to the outcome of the

audit, the committee recommends the government consider taking proposals to the

Council of Australian Governments (COAG) for discussion.

Recommendation 21

6.98

The committee recommends that universal free vaccination be

extended to the babies and children of all temporary migrants living in

Australia, irrespective of their visa status.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page