Chapter 2 - The question of labour shortages in horticulture

You have to understand that agriculture-horticulture is a

peasant industry. We cannot avoid that. All around the world, in every country

you go to, it is regarded as a peasant industry ... [P]eople do not want to be

out in the sun in the middle of summer doing labour work in horticulture.[1]

2.1

The sentiment expressed above struck the committee as giving an

indication of why horticulture struggles to recruit sufficient harvest labour.

While there may be social and demographic causes of a labour shortage, there

are also residual cultural and attitudinal difficulties. Many growers are aware

of this. If only a few growers regard their seasonal workforce as 'peasants',

then they are scarcely likely to look to ways of improving wages and conditions

in order to attract more labour. The committee acknowledges that a majority of

growers would not hold such views, including large family-run concerns which

attract a core of long-standing 'regulars' year after year, as well as the

newer corporate managed properties. The committee sees the difficulties

involved in changing an employment culture where it is needed, but believes

that growers and their representative organisations are responsible for doing

so, for the benefit of the industry.

2.2

The most important evidence the committee heard during the inquiry

concerned the nature and extent of labour shortages in the horticultural

sector. Growers put their personal experience on the public record, and the

committee held a number of informal discussions with farm managers, growers and

investors which revealed a great deal about attitudes and practices in the

industry. A characteristic of this inquiry has been the absence of empirical

data, and the difficulty of interpreting anecdotal evidence.

2.3

The committee's primary aim was to evaluate evidence to estimate whether

a current industry-wide labour shortage is more of a perception than a reality,

and to consider whether despite fluctuations in the demand and supply of

labour, the needs of growers can be adequately covered by the current pool of

labour. This chapter focuses on the first two terms of reference which relate

to the nature and extent of labour shortages in horticultural regions, the

availability and mobility of the existing pool of labour, and the likely effect

of importing seasonal workers from Pacific island nations on the current

available seasonal workforce. It reviews the evidence given by growers who

described their difficulties finding reliable seasonal labour and the resulting

financial strain and loss. It also notes the view that labour supply may be

less a problem than inadequate planning by growers: that shortage of labour is

usually temporary and of short duration. This chapter also examines the nature

of the current seasonal workforce, which consists mainly of backpackers, the

'grey nomads' and local workers, and government funded programs including the

Working Holiday Maker (WHM) scheme and the National Harvest Trail. The final

sections consider evidence from witnesses and published sources to establish

whether the industry currently faces a labour shortage or whether it should be

taking measures now to overcome any future labour shortage.

Seasonal work: a profile

2.4

Some comments need to be made at the start about the nature of seasonal

work. The committee was reminded by a manager of a packing firm on the

outskirts of Darwin that seasonal workers are at the bottom of the employment

food-chain in terms of wages, conditions and skills. This contributes to the unreliable

nature of seasonal work, and the unreliability of seasonal labour supply. growers

stressed that fruit-picking is hard, hot and dirty work requiring long hours

exposed to the elements. There is no escaping the fact that harvesting crops –

picking fruit, pruning trees, working in a packing shed – is physically

demanding work. During the summer months when many crops are ripe for harvest,

workers routinely spend eight to ten hours a day, six days a week, in the

field. Much of this time is spent up a ladder, bending over or on hands and

knees picking fruit and thinning bushes, one row at a time. The occupational

hazards of picking fruit are ever-present, especially in the mango industry.

The committee was told in detail how sap from a mango cutting, which squirts in

all directions, can inflict serious burns when it makes contact with exposed

skin.

2.5

The harsh conditions and occupational risks associated with seasonal

work were mentioned by a number of witnesses as a key reason why farmers and

labour hire firms find it difficult, and sometimes impossible, to attract

itinerant workers and the unemployed to seasonal jobs in the horticultural

industry. While some growers expressed disdain for the absence of a work ethic

among the long-term unemployed, there were also those, and others associated

with the industry, who understood the difficulties faced by people in this

position who were faced with the prospect of hard manual labour. These

circumstances are dealt with in more detail further on in this chapter.

2.6

Backpackers are, for an increasing proportion of growers, the backbone

of the harvest labour supply. They are simultaneously growers' most important

asset and the source of much of their frustration. The energy of backpackers

and their willingness to work long hours is seldom matched by a commitment to

stay with one grower to the end of the harvest. The committee heard variations

on a familiar theme in relation to backpackers: they have a habit of flocking

to the beach when the surf is up. The committee heard of workers, mainly the

backpackers and unemployed, lacking motivation to stay on the job for more than

one or two days and physically wilting after a few hours in the sun. This is

more common in the Northern Territory where the combined effects of heat and

humidity take their toll on seasonal workers, most of whom who are ill-suited

to working outdoors in extreme tropical conditions.

Characteristics of the horticultural industry

2.7

Horticulture in Australia is big business, to the extent that many in

the industry consider it an important part of the wider agribusiness economy.

Investments from large agribusiness companies such as Timbercorp,

SAITeysMcMahon and Select Harvests extend to all aspects of farm management

operations from water use and irrigation monitoring to marketing. As one farm

manager told the committee: 'We provide the whole value chain from seed to

supermarket'.[2]

2.8

The horticultural industry is highly labour intensive, although

mechanisation is advanced in some crops, including viticulture (except table

grapes) and almond plantations. Despite extensive research no way has been

found to strip citrus fruit from trees mechanically, and a range of soft fruits

and vegetables also require to be picked by hand. The investment currently

taking place at the high technology end of agribusiness cannot overcome

growers' reliance on unskilled seasonal workers doing what they have been doing

in the industry for hundreds of years; hand picking crops.

2.9

During its visit to Darwin the committee was impressed by the technology

which enables the Territory's mango industry to export a small percentage of

its crop to the lucrative Japanese market. It has been able to break in to this

market by a sophisticated treatment process which satisfies Japan's stringent

quarantine requirements. Yet, the multi-million dollar facility inspected by

the committee would be useless without a seasonal influx of backpackers to

harvest the mango crop in the first place. The risk management factor here is

clearly the gamble on labour, with world-class technology dependent on the

uncertain labour supply. The labour-intensive nature of horticulture has

created new pressures for growers. Domestic and international markets which

demand a blemish-free product place the onus on growers to properly train

seasonal workers in the art of hand picking crops without damaging either the

fruit or the trees. This adds significantly to the cost of recruiting and

retaining seasonal workers with appropriate skills and experience.

2.10

Horticulture Australia estimated in 2005 that 17 273 horticultural

enterprises employed a total of 64 000 people, or about 20 per cent of the

agriculture sector employment, but admits this is likely to be an

underestimate. The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations 's 1999 estimate

of the workforce was between 55 000 and 65 000 equivalent full-time positions.

This would explain the wide variation in estimates. Brebners' Walkabout

Australia surveyed the major recruitment agencies and estimated the number of

seasonal positions at 175 000. This is also an underestimate because it does

not include seasonal workers hired direct by growers and does not include

full-time employment.[3]

Labour costs average 30 per cent across the industry, but there is wide

variation.

Investment, expansion and future

labour requirements

2.11

Two issues stood out during the committee's hearings and site visits:

the scale of investments on the one hand, and on the other, the apparent absence

of any systematic planning by the industry on its future labour requirements.

The committee is surprised at the industry's apparent complacency in regard to

labour-force planning This is a critical variable in what is (and will remain)

a labour-intensive industry. The committee detected an attitude from some

sections of the industry that sourcing adequate labour in the future was

someone else's problem and that labour shortages would be addressed one way or

another by the market.

2.12

The committee is surprised that large investors argue that labour

shortages are currently a problem within the industry, yet have not given any

serious thought to what their future labour requirements will be and how the

new anticipated demand will be met. There is even a concern in some quarters

that failure to expand the seasonal workforce will place restrictions on the

investment and expansion opportunities of companies which invest heavily in

horticulture. A question before the committee as it visited hectare upon

hectare of new plantings: 'who is going to harvest the crops when they reach

their full carrying capacity, and where is the labour going to come from?'

Growers, farm managers and investors were unable to answer these fundamental

questions.

2.13

This complacency results in mixed messages being sent by the industry in

regard to labour. For instance, Growcom, the umbrella organisation for the Queensland

horticulture industry produced a future directions paper with assistance from

the Queensland Department of Primary Industries and Fisheries during 2006 which

scarcely mentions labour shortages. In a list of 'our responses to the forces

of change' there is recognition, among other things, of consumer lifestyle

changes, global trade issues, biotechnology, transport and supply chains, but

no reference to labour. In a separate list of 15 evolving issues labour

shortages come in at number 14. The committee accepts that glossy marketing

brochures like Future Directions are targeted at investors, and this might

partly explain why many investors in horticulture remain oblivious to the

labour issue.

2.14

Growcom assisted the committee to organise its Queensland visits and

made a valuable submission to the inquiry, in which it stated that the

availability of human capital was a matter important concern. There was a

critical need to take action to reduce the potential for serious risk to the

industry in the future. It quoted from its own survey in 2005 of employee

perceptions of the reasons for labour shortages. The results included low wage

rates, poor image, physical demands, tough working conditions and poor recognition

of skills development.[4]

The committee notes the consistency between these findings and much of the

anecdotal evidence given by the producers whom Growcom represents, but it makes

the point that conflicting messages in its future directions paper about the

current state and future prospects for the industry in relation to its labour

needs do not assist in the making of good public policy.

Wages and conditions of employment

2.15

The committee was told by some growers that fruit pickers can earn

upwards of $1 200 a week. However, the committee believes that the capacity for

seasonal workers to earn this amount is limited. Figures of this magnitude

paint a distorted picture of the earning capacity of seasonal work in

horticulture. Seasonal workers at the higher end of the income scale within the

industry are often among the very small proportion who return to the same

employer each year. Their objective is to earn as much money as possible in the

shortest amount of time before moving to another region where there is demand

for labour, often with little or no warning given to the employer.

2.16

Growers were eager to assure the committee that they paid the award rate

as a minimum. That is, if pickers and packers failed to earn the higher piece

rates, their safety net was the award. The committee notes that award rates for

this kind of arduous work are very low, averaging around $15 an hour.

Coincidently, that happens to be about the rate that backpackers are prepared

to accept, and is probably quite ample for the maintenance of their transient

holiday lifestyle. The committee did not receive a great deal of information on

pay rates, but it appears that they vary considerably. Yandilla Park, a

property near Renmark, submitted that piece-rate workers, once trained, would earn

about $20-25 an hour.[5]

2.17

A submission from an experienced picker argued that the problem of

labour scarcity was compounded by the low pay rates offered to locals and

domestic itinerant pickers. It was submitted that the setting of piece rates

was unrealistic and unfair, and was inconsistently tied to the casual minimum

award rate. Experienced pickers would expect to earn piece rates that were

consistently above the minimum rate but this was not always so. Some average

pickers earn less than the minimum award rate, and it takes years of experience

to earn a reasonable income.[6]

2.18

The committee was told by a picker with over 20 years experience that

piece rates did not necessarily result in higher wages. This very much depended

on the quality of the crop. Orchards vary in quality of management and

therefore productivity, which means that some trees are harder to pick than

others, due to the variability of quality and ripeness of the fruit. That is,

on some orchards, a picker may spend time grading the fruit being picked, thus

slowing down the speed at which a bin may be filled. Under these conditions,

there may be no advantage to working at piece rates over casual rates. Only

during exceptional weeks may an experienced picker earn well above the award,

which would become close to the average wage for the season. [7]

2.19

It is unlikely that many pickers would know by how much piece rates were

worth more to them than casual award rates. Piece rates are local and variable,

usually subject to arbitrary and sudden change. According to anecdotal evidence

they are often set so low as to make little difference to the earnings of

pickers, especially when the quality of the crop is poor.

2.20

The committee heard from growers that the cost of labour, primarily

through wages and training, represents a significant economic 'burden'. They

claimed that they could not pay much more than they did and still cover their

costs. The committee believes that growers will always be able to cover costs

in normal seasons, even at rates above the current awards. Growers were

insistent that bringing workers from abroad would not exert downward pressure

on wages and conditions because horticulture could not afford to lose workers

to industries like mining, especially in southeast Queensland and in the Northern

Territory. Nonetheless, the committee warns that imported labour schemes,

unless properly regulated may have the effect of 'quarantining' this industry

from the labour market forces that affect all other sectors of the economy.

This would be undesirable, and would operate to the detriment of local harvest

workers, and possibly to workers in related industries and occupations in the

districts where imported labour was used. The committee also believes that the

increasing proportion of backpacker labour may already be distorting harvest

wage levels. As their purpose in travelling is essentially recreational rather

than related to livelihood, backpackers accept low pay as normal. Thus their

employment is allowing a downward pressure on wages, even though the

inefficiencies of their workforce participation result in additional costs to

growers.

Investment, expansion and future labour requirements

2.21

The relationship between investment and labour planning remains, at the

conclusion of the inquiry, the one big unknown for the committee. The committee

visited properties where large-scale investments that have occurred in recent

years are close to full production. However, it was difficult to find aggregate

figures on the amount of investment that is occurring in the industry. Nor

could the committee find out if investors and the farm managers had calculated

their likely profit on the basis of an uncertain labour supply.

2.22

In some places the committee was given a glimpse of the problem. The

Swan Hill City Council submitted that 22 major developments had recently

commenced in the shire, with almost $850 million being invested, taking up 23

000 hectares. Much of this was for almond plantations, which are not labour

intensive. Even so, the estimated additional labour need was for 1 000

full-time equivalent new jobs, and an additional 800 indirect jobs. This

greatly exceeds the current workforce of 650.[8]

2.23

Some of the largest investments are occurring in the almond industry.

One agribusiness manager told the committee that by the late 1990s the company

was managing 4 000 hectares or 7 000 tonnes of almonds. By 2012 this is

expected to increase to 20 000 hectares and 50 000 tonnes of almonds. This will

equate to a seven-fold expansion in the industry resulting in a seven-fold

increase in the demand for labour. Most almonds are grown along the Murray from

Robinvale west to include the South Australian Riverland. This is also an area

of intense citrus cultivation, which is a labour intensive operation. According

to one submission, 50 per cent of naval orange trees along the Murray have yet

to come into production. The figure for the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area is 30

per cent.[9]

2.24

The committee did hear the voice of misgiving on one or two occasions.

At the committee's public hearing in Renmark, the Managing Director of one

agribusiness company, Yandilla Park Pty Ltd, described how the current

agribusiness environment in Australia:

...is undergoing significant change at this time. There is a

change in the dynamics of the power base as well and certainly the amount of

money that has been invested in that business. We feel that this is a critical

point that could be endangered by not having the right policies going forward

on availability of labour.[10]

2.25

On a separate but related matter, new and continuing investment

initiatives need to be seen in the context of a changing retail trend. The

committee was told how over the last 20 years, retailing of horticultural

produce has become dominated by the two major retail chains, Coles and Woolworths,

which aim to supply, promote, price and move fresh produce off their shelves as

quickly and as cheaply as possible. One witness described modern-day

supermarkets as 'real estate agents for square metres of shelf-space'. This

relentless push by large retailers, foreign and domestic, for a globalisation

of supply chains and a consolidation of economies of scale sits uneasily

alongside the management practices of most agricultural and horticultural

operations. The committee was told that most domestic suppliers are fragmented,

with logistics locally based. It is normal for the marketing of fresh produce

not to be directed to the end consumer but to take place between the farm and

the packing sheds.

2.26

Labour market policy makers in the horticultural industry have some

challenges ahead in planning the labour needs of the industry at a time of

production expansion and a declining domestic workforce. The committee believes

that the government needs to take a bold attitude in considering any long-term

planning.

Likely costs to growers of a

harvest labour scheme

2.27

The question has arisen of whether the cost to growers of having the

benefit of assured labour would be worth the additional cost. It is almost

certain that there would be additional cost, though much of it may be recouped

from the workers. Professor Helen Hughes, a critic of any Pacific labour

sourced harvest labour scheme, has included insurance as a new cost to be

absorbed, in addition to meal and accommodation costs. The World Bank has

estimated additional hourly costs of just over $2 for workers staying between

six weeks and six months.[11]

2.28

The government has estimated much higher costs of up to $30 per hour,

although this does not appear to have had any cost recovery factored in, if

news reportage can be relied on. Minister McGauran was quoted as saying: 'if

producers offered $25 to $30 an hour to pickers there would be a stampede from

Australians'.[12]

It is not clear from the evidence to this inquiry that such a 'stampede' would

be the result, although anecdotal evidence suggests that significant wage

increases can attract pickers to farms which advertise them, presumably away

from farms which do not offer them. The committee does regard harvest labour as

being, in general, too poorly paid. Growers pay poorly because the supply of

labour does not seem to be affected one way or the other by wage rates. Growers

say that more pay will not attract more workers because only a limited number

of people wish to work on the harvest trail. It was not clear however, that this

is a claim based on presumption rather than experience.

2.29

There is anecdotal evidence, however, that at least some growers, and

particularly large corporate operators, would be prepared to pay a premium for

scheduled, organised and reliable labour teams which would be possible under a

harvest labour scheme.

Characteristics of the current seasonal workforce

Backpackers, 'grey nomads' and the

local workforce

2.30

Where does harvest labour come from? It depends on location and the

produce that is being harvested. Traditionally, the labour market was served

for the most part by local people who maintained connections with the same

growers year after year. Backing them up was a substantial force of

professional itinerant pickers who moved across the country depending on the

season. These included shearers and cane cutters. Demographic changes and

population movements have seen a marked decline in the availability of this

workforce over the past ten years, and this trend continues. As the chart below

shows, local labour is still important, but backpacker labour is taking the

place of both local and traditional itinerant labour.

Sources of seasonal labour

Source: Growcom and

Horticulture Australia Limited Horticultural Labour Situation Statement, June

2005.

2.31

There been a clear trend toward increased reliance on backpacker labour

as the pool of local itinerant workers and 'grey nomads' appears to be in

steady decline. Although the figures vary across regions, backpackers

consistently make up approximately 50 to 85 per cent of the current seasonal

workforce, a figure which appears to be on the rise. Growers in and around

Kununurra in the Northern Territory rely almost exclusively on backpackers. The

'grey nomads' and itinerant local workers would typically make up the remaining

20 to 25 percent of the seasonal workforce. Apart from the high percentage of

backpackers who make up the seasonal workforce, many growers rely on a core but

diminishing group of itinerant workers who return each year. The number of

itinerant workers appears to be declining as the workforce ages, which means

that growers are finding it more difficult to attract people with commitment

and experience. In a number of cases this is adding significantly to the

administrative cost of attracting, training, inducting and retaining workers

and causing a loss of farm productivity.

2.32

Backpackers make up the majority of itinerant workers on the harvest

trail. The committee found that the view of growers and producers across the

country was fairly uniform on the work performance and limitations of

backpackers One labour contractor described backpackers as:

young, fit, attractive, unencumbered, flexible, educated,

multi-lingual – in fact, all the things that most employers want. Their demands

are few and if they don't work out there are plenty more. I believe that the

horticulture industry will face some stiff competition to attract their

services in the future.[13]

2.33

Some submissions pointed out the tax disadvantage under which

backpackers worked. Backpackers pay 29 per cent tax compared to a local worker

rate of 13 per cent. Studies show that backpackers spend as much as they earn

in the local community and are important to local business. The 16 per cent

difference 'goes to Canberra and disappears'.[14]

2.34

Backpackers have become a mixed blessing for most growers: indispensable

for most of the year on the one hand, yet unreliable during peak harvest times

on the other. While most growers depend to a large extent on backpackers to

harvest crops, they are not considered the ideal source of labour for a number

of reasons. One farm manager in South Australia's Riverland, in referring to

backpackers as 'floating labour' on an extended holiday, painted an

industry-wide picture which captured the unreliable nature of backpacker labour:

It is a timing thing. For all of us ... it depends on the crop

base that is coming off at the time. Apricots come through in November to

January. It is a critical time. There are Christmas Holidays, New Year's

parties and everything else and basically nobody wants to work. There is a big

party in Manly every year that all the backpackers in Australia want to head

to, so they all focus on being in Manly. That is a fact of life.[15]

2.35

Notwithstanding the necessity to employ backpackers, Growcom submitted

that many growers were reluctant to employ them because they were transient,

and limited by the conditions of their visas to a maximum three month

employment at any one farm; they usually moved on by the time they had become

most efficient; and, because they have a 'working holiday' attitude, they were equally

carefree in relation to reliability and work quality.[16]

The National Harvest Trail

2.36

The government has responded to the increased demand for harvest labour

in two ways. It has liberalised employment opportunities for young backpacker

travellers, and it funds a network of contracted employment agencies known as

the Harvest Trail to have available itinerant labour, mostly backpacker,

directed to where it is needed. The National Harvest Guide is distributed to backpackers,

'grey nomads' and other itinerant workers.

2.37

There has been dissatisfaction expressed by some growers as to the

usefulness of the Harvest Trail. This is sometimes aired in the rural press and

other media. The Mildura Harvest Trail agency, known as MADEC, submits that

most of the criticism directed at it by growers is misinformed. It points out

that many growers are not registering with MADEC, but complain when their

urgent call for workers cannot be met.[17]

2.38

The Department of Employment and Workplace Relations investigates

complaints made by growers. In 2005 it investigated several claims of a

shortage of harvest labour which were reported in the media, and found that

there was little hard evidence of labour shortages in areas from which the

claims originated. DEWR claimed that reports of labour shortages were often

exaggerated. They were generated by growers anxious to attract more itinerant

labour to their districts. It further suggested that such stories are generated

for the purpose of strengthening support for a foreign worker scheme.[18]

2.39

From what the committee is able to glean from the conflicting evidence,

the performance of MADEC, and the other agencies in the Harvest Trail network,

is not in question. Its approach to its task seems highly flexible and

responsive. Dissatisfaction with its performance probably owes much more to an

inherent suspicion about the effectiveness of quasi government agencies, and

the venting of grower frustration in regard to a whole range of labour shortage

issues, many or most of which are beyond the capacity of the Harvest Trail

network to deal with.

Is there currently a labour shortage?

2.40

Employment in the agriculture sector generally has been in decline over

the past six or more years because of seasonal factors. The main reason has

been the persistent drought, but there are other underlying pressures which

will almost certainly mean that pre-drought levels of employment in agriculture

will not recur. Farms are being consolidated, and there is a drift from rural

to urban employment generally, in line with economic and social trends. The

graph on the next page illustrates this trend:

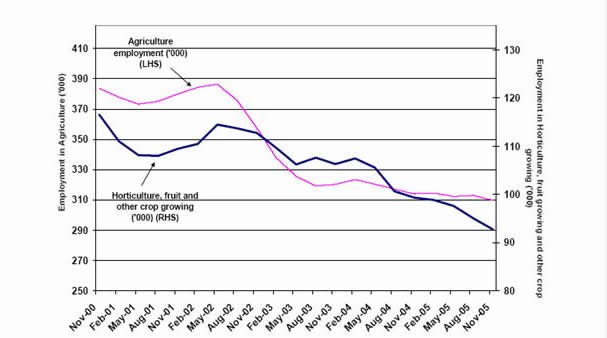

Employment in agriculture,

horticulture, fruit and crop growing, November 2000 to November 2005[19]

2.41

Can the labour shortage be verified through evidence of financial loss

to growers? The committee received some evidence that labour shortages resulted

in unpicked crops in several areas. Horticulture Australia cited in its

submission several instances which were reported originally in research conducted

by Mr Peter Mares in 2005. These included: a reported 150 tonnes of asparagus

(30 per cent of the crop) worth $1 million left in the ground on a Queensland

farm for want of available labour; lower than expected production at the

SPC-Ardmona cannery at Shepparton because insufficient labour resulted in fruit

remaining on the trees; and, a Yarra Valley berry farmer forced to drop 6

tonnes of fruit because of a shortage of labour.[20]The

submission from Growcom referred to one grower who had been able to demonstrate

a loss of $100 000 in 2005, caused by the loss of 10 000 cases of produce as a

direct result of a labour shortage.[21]

2.42

The committee notes that The World Bank has recently reported that crop

losses due to labour shortages have been estimated at $700 million.[22]

It appears, from the way in which this estimate is presented, that The World

Bank is not endorsing this figure, which is based on estimates supplied by

growers associations, and rests ultimately on little more than the kinds of

anecdotal evidence that was provided to the committee. It was the experience of

the committee, and may be a characteristic of dealings with small businesses

and family farms, that hard evidence on financial matters is not easy to prise

out of small proprietors. Only such losses as would be compensated for by a

statutory entitlement or tax concession would ever be revealed to a holder of

public office!

2.43

Therefore, apart from the instances given in preceding paragraphs,

financial loss was not widely reported. The committee does not know whether

such losses were widely experienced, but it is inclined to believe they are

not. Nor have the circumstances of the losses cited above been explained. They

may have as much to do with poor labour planning and management than a genuine

scarcity of labour. They may also be connected with problems over pay and

general regard for harvest workers.

2.44

If anything, the anxiety caused by the competition for labour, and the

apprehension that is associated with the success or otherwise of the crop and

its harvesting, is more stressful than any real labour shortage. These

anxieties compound. Growers described being forced to schedule their

cultivation on the assumption of an unreliable labour supply and having to work

40 hours without rest just to stay on top of their business. One farmer from

Mildura, having completed a ten-month period harvesting table grapes, explained

why growers become highly stressed in their task of employing and managing

seasonal labour: 'I now get eight weeks off and I really need it ... [H]alf the

labour I have had has been excellent, but for the last 10 to 12 weeks the other

half has been an absolute nightmare'.[23]

He went on to describe the tension of dealing with seasonal workers who were

regularly ill-behaved; who had to be bailed out of prison on drink driving

charges, or who had injured themselves while drunk or become drunk during their

meal breaks.

2.45

The committee heard that labour-related problems for the industry do not

end there. Evidence from the horticultural regions of southeast Queensland and

the Northern Territory suggests that competition from other industries,

especially mining, is depleting the pool of available labour. Growers are not

able to compete with sectors which pay their workers higher wages and where the

work is not as physically demanding. Witnesses warned that labour shortages in

horticulture will soon reach crisis point, with dire consequences for the

industry. The committee was told that demand for seasonal labour is growing

steadily on the back of corporate investment and long-term structural change,

both of which show no sign of slowing.

2.46

While many growers admitted to having met their labour requirements

during the most recent harvest, they claimed the situation would be different

in the next one or two years. Most of the evidence painted a disturbing picture

of an industry teetering on the brink of a labour-shortage crisis, compounded

by domestic and international pressures. A few of the larger growers and farm

managers could estimate what their future labour requirements would be, while

others simply did not know and were vague about the extent of the labour

shortage when asked by the committee. As the committee travelled the regions

talking to farmers and receiving evidence, it navigated its way through gloomy

prognoses regarding the industry's ability to attract enough unskilled workers

to meet the strong demand for labour that many in the industry have predicted.

2.47

The graph below is of a World Bank survey of grower opinion on the

relationship between labour supply and industry expansion.[24]

It supports the committee's view that current supply is adequate but that the

outlook shows no cause for complacency.

2.48

Yandilla Park Pty Ltd, a large horticulture operator in South Australia's

Riverland, submitted that the labour shortage worsens each year. Between May

and October 2005, the picker turnover rate was 300 per cent.[25]

With a decline in available local labour, Yandilla Park is obliged to rely on

more backpacker labour, which is described as a 'reliable source'. The

committee believes that perceptions of labour shortage may be more common among

those growers facing a sudden transition, over two or three years, from the use

of local or regular itinerant labour to increased use of backpackers. For other

growers, who have traditionally relied on backpackers, perceptions of labour

supply may be optimistic.

2.49

The demand for labour is very high in the Goulburn valley. Growers have

commented that the pear crop of around 140 000 tonnes requires at least 2 000

pickers a week for six to eight weeks. Given that 50 per cent of the workforce

now comprises backpackers, the total number of workers involved for those weeks

is in the order of 15 000 due to high turnover.[26]

2.50

The question of whether an underlying labour shortage exists is the most

important question for the inquiry. There is no clear-cut answer, but as the

preface to this report indicates, the committee has, with reservations, come

down on the side of the argument which asserts that there is not. Some of that

evidence is set out and assessed in this section.

2.51

The committee believes that in the absence of manifestly clear evidence

of an unreliable supply of fruit and vegetables which would be apparent to

retailers and consumers, there is an onus on growers and producers to

demonstrate the validity of a claim of labour shortages. This inquiry was

undertaken on the basis of arguments that labour shortages were a problem, and

that a radical plan to import unskilled foreign labour was essential to

maintain the prosperity of the industry and the supply of fresh produce for

both domestic consumption and export markets.

2.52

The committee believes that many growers continue to experience labour

shortages at critical times during the year, such as harvesting. Financial

hardship will inevitably follow any drying up of seasonal labour, especially

growers for whom backpackers on Working Holiday Maker (WHM) visas constitute

nearly their entire pool of labour. Yet the committee did not gain the

impression that the current pool of seasonal labour, especially among the

backpacker population, was about to dry up. There appears instead to be an

enthusiastic response to the WHM scheme. The committee has no reason to doubt

what growers in each of the regions it visited had to say about difficulties

finding reliable seasonal labour. Growers were eager to tell the committee of

their genuine concerns not only about getting this year's crop harvested and to

the consumer on time, but also about the future sustainability of their

industry given the economic and social challenges facing rural and regional

areas. The committee heard how the twin pressures of competition from

international markets and a domestic market which demands near perfect

(blemish-free) fruit is beginning to take its toll, especially on small

growers. It is their wherewithal to plant and harvest a crop each year that

would probably not withstand a major economic downturn in the industry,

whatever the reason.

2.53

A theme running through the evidence is that the nature of seasonal work

in the horticultural industry is a major factor contributing to the irregular

supply of labour – much of it is physically demanding and peak harvest times

often coincide with extreme weather conditions, especially in the Northern Territory.

The managing Director of Simarloo Pty Ltd, Mr Noel Sims, told the committee

that unless workers are from a rural background, they are not suitable to

harvest specific crops. This results in workers being employed 'who in most

cases are totally unsuitable for our or anyone else's needs'.[27]

Attracting unemployed and indigenous workers

2.54

Critics of a foreign contract labour scheme to provide unskilled labour

are ready to point to the loss of job prospects or the displacement from the

labour market of local unemployed and indigenous people that will result. The

committee was careful to raise this prospect with such witnesses who could be

drawn to comment on the issue.

2.55

The committee received a strong message that the long-term unemployed

appeared to offer no prospect of providing a pool of suitable harvest labour.

The experience of growers who dealt with unemployment benefit recipients

required to seek jobs appeared to be similar in the major cultivation areas. A Goulburn

Valley witness told the committee:

One of the issues with harvest labour is that it is probably not

a job that is that suitable for someone who has been long-term unemployed—I am

not saying that we do not put them on; we do. We put on everyone who comes

through the gate. But it is probably fairly challenging for someone who has not

been working for a long period of time. There is probably a place for some

scheme that assists them. If we are going to employ them and give them a start

again, which we would happily do, there needs to be a scheme that assists them

because it is hot, hard, laborious work. For someone who has not worked for

five or 10 years, for long-term, entrenched unemployed people, getting their

heads around that activity is quite a challenge.[28]

2.56

Labour contracting firm Worktrainers, also from Shepparton, submitted

that government policy to get people on unemployment benefits to take up

harvest labour should be declared a failure. The majority of people on welfare

were incapable of the hard work of picking fruit. Moreover, sending large

numbers of incapable workers to a region is a severe drain on local welfare

services. This is a case of moving a problem from one place to another, and of

being seen to be doing something rather than nothing.[29]

2.57

The committee accepts this argument. Few unemployed people without

experience in the field would remain at the job long enough to acquire the

necessary level of fitness, or the skill to earn much above the minimum rate.

The committee accepts that anyone eligible for unemployment relief would have

entered the harvest workforce of their own volition if they were so motivated.

It rejects, therefore, the argument that any perceived obligation to the

long-term unemployed is a valid reason for rejecting the idea of unskilled

foreign labour.

2.58

Indigenous people, 60 per cent of whom are unemployed, are also seen as

a potential source of horticultural labour. The evidence for this appears to be

based on wishful thinking, as it is for the long-term unemployed generally. The

committee questioned indigenous leaders, when it visited Darwin, as to the

potential for the involvement of indigenous people in the industry in the Northern

Territory where growers are hard pressed to find labour and where the

dependence on backpackers is most evident. The response to the suggestion was

unequivocal. The Deputy CEO of the Northern Land Council told the committee

that:

[S]easonal short-term low-paid labour that is not on Aboriginal

land does not fit the profile of the stated aspirations of most Aboriginal

people in the Northern Territory, nor does it fit within the parameters of the

jobs and career service or the stated aims of the Northern Land Council.[30]

2.59

The committee heard later from the Northern Land Council of instances of

indigenous people from missions working in horticulture; of regular grape

harvesting trips from the Hermannsburg Mission to the Barossa, and of similar

expeditions to the Riverina and Victoria. These were cited as past instances of

success, with no suggestion that they should be repeated.

2.60

From informal conversations with growers, the committee heard that

indigenous workers in the industry were quite rare, and that there was an

evident lack of interest in harvest work. For instance, in Shepparton the

committee heard from a tomato grower that he had been offered four indigenous

workers as trainees, but that this arrangement had not eventuated. The trainees

were reported to have subsequently worked briefly at the SPC cannery.[31]

2.61

The committee's assessment of the chances of attracting indigenous

seasonal labour is that it is unlikely to succeed, and the reasons may be

similar to those which apply to the long-term unemployed. The committee senses

that there appears to be a view that the horticultural industry has a role in

absorbing unwilling workers. Willingness to work appears to be the most

desirable characteristic of the harvest worker, for otherwise no work would be

done. This presents a challenge to community service experts rather than

growers, who have other things to do than to run work induction programs. As

one grower told the committee: 'if I spend most of my time driving these

[unwilling] guys around or trying to get them orientated to work or teaching

them how to work versus someone who can do the work, there are some advantages

to me in just having someone who can get on with the job.'[32]

Accommodation

2.62

The significant decline in the proportion of local labour available for

harvest work has put additional pressure on the accommodation available for

itinerant workers, and poor accommodation standards are a deterrent to labour

mobility. Only those with caravans have the assurance of finding somewhere

decent to stay.[33]

Even then, the committee was told that some caravan parks did not accept

itinerant workers because they could charge more for tourists. The lack of decent

and affordable accommodation and transport was a problem in some harvest

regions.[34]

Few growers or grower organisations had developed considered views on

accommodation as a factor in attracting labour. For those on the heavily

travelled harvest trails in Queensland and the Murray-Riverland and Riverina

areas the backpacker hostels and caravan parks labour provide a partial solution

to the problem.

2.63

Fundamental to the issue of a pilot scheme is provision of adequate

accommodation and community support for seasonal workers. These are among the

administrative and practical issues which will need to underpin a contract

labour scheme. These issues are examined in detail in Chapter 4. There is a

tendency within the industry to view accommodation as 'someone else's problem'

and to put off thinking about providing adequate worker accommodation. This is

especially true in regional towns such as Robinvale where housing vacancy –

public, rental or private – is already almost non-existent. The on-site accommodation

facilities which the committee inspected on farms on the outskirts of Katherine

and Darwin are at best rudimentary structures to accommodate a transient

backpacker population. They were built specifically for the backpacker

workforce and would require a significant upgrade to meet even minimum

community standards were they to house foreign guest workers. Even where

accommodation on farms is of a reasonable standard, it is often not maintained

in good order, or cleaned up properly for successive occupants. Given the fact

that Northern Territory mango plantations are heavily dependent on backpacker

labour, while local and domestic itinerant workers diminish in proportion every

year, this solution fits the times and the expectations of pickers.

2.64

Yet even these backpacker–standard facilities, which include toilet and

shower blocks, cooking sheds and in one instance a proposed recreation shelter

to be located away from the main sleeping quarters, required a considerable

financial outlay. One grower in Darwin told the committee that $100,000 would

eventually be spent on rudimentary facilities to accommodate backpackers. This

sum is likely to be beyond most growers in the industry. This does not alter

the fact that more will need to be invested in providing proper accommodation

for seasonal workers from Pacific nations under a contract labour scheme.

Important questions remain unanswered; for example, where is the money going to

come from and who is going to pay?

Summary of the evidence

2.65

Despite the concerns raised by growers, farm managers and investors the

committee is reluctant to conclude that the horticultural sector is currently

experiencing a systemic and widespread shortage of seasonal labour. A labour

shortage of this magnitude is not supported by consistent evidence. Were this

the case the committee would have expected to witness failed crops and closed

farms dotted across the country from Sunraysia in the south to Katherine and

Kununurra in the north. It also would have expected there to be reluctance from

major investors to plough superannuation funds in to new and large-scale

horticultural enterprises through managed investment schemes. This definitely

was not the committee's experience. The committee visited thriving and

expanding horticultural regions which, from the air, resembled large oases in a

sea of marginal agricultural country suffering from the combined effects of

environmental stress and drought.

2.66

Nor does the anecdotal evidence point to a demonstrated industry-wide

labour shortage. The committee in its travels did not talk to one horticultural

producer, large or small, who, at the end of the day, could not find enough

labour over the previous one or two years' harvest. The Director of Tree Minders

in Robinvale confirmed that he had been successful in sourcing all of his

labour requirements for the almond industry in Robinvale.[35]

Although many small growers complained about labour shortages, the number of

extra workers required for many growers to achieve an optimum labour force

often boiled down to as few as ten or fifteen. This suggests an underlying

confidence within the industry to withstand and overcome, for the time being,

fluctuations in the supply of seasonal labour, no matter how disruptive they

are to the smooth and efficient running of horticultural operations. How else

to explain the thousands of hectares of prime horticultural land floating on a

sea of investment dollars, which the committee witnessed first hand? Those with

economic clout in the industry clearly think big picture, long-term and

competition with international markets, not small scale, short-term and meeting

only domestic consumer demand.

2.67

The committee detected resilience even among smaller growers, given

their livelihood depends on harvesting every crop. For most growers there is no

option but to find suitable labour when required, often at very short notice.

While many growers struggle every year to find reliable, experienced, committed

and hard working labour, it appears that with much annoyance and frustration

the difficulty is overcome. Recent changes to the Working Holiday Makers Scheme

and further refinement of the National Harvest Trail should result in positive

outcomes for growers, and will continue to reduce labour shortages. There is

also room for growers to make more effective use of the employment services

which organisations such as MADEC provide.

2.68

As previously discussed, the committee is surprised by the lack of a

workforce planning program to support the multi-million dollar investments that

have taken place in the horticultural industry over recent years. The committee

is concerned that investors such as SAITeysMcMahon, to take one of many

possible examples, has invested millions of dollars establishing new

plantations across different regions on the assumption that future demand for

labour will be met. Yet the company's director of agribusiness, expressed the

view that a labour crisis was a distinct possibility in the medium to long term

given that many horticultural regions currently experience a zero unemployment

rate. In telling the committee of the significant advantages that flow from his

company's investments, including the regional multiplier effects of employment

and industry expansion, he also warned of the risk: 'The high risk in all this

is that these growth models may stall if a labour expansion policy is not

adopted. In my view we have effectively zero unemployment in areas where it

counts—in other words, at peak labour times ... we cannot get labour'.[36]

2.69

The committee believes major investors have an over-optimistic view that

the market will (somehow) take care of future labour shortage and that

shareholders will receive a healthy return on their investments. The committee

speculates that in undertaking their risk assessments large horticultural companies

have transferred some of the risk of there not being a guaranteed future labour

supply from 'the market' to governments. There could be an expectation that

state intervention will be necessary to bail out producers who experience

financial trouble as a result of a labour shortage, and to prevent an

industry-wide collapse on the back of an acute labour shortage. This could

prove to be a high risk and foolhardy strategy given long-standing government

policy on the importation of unskilled labour. There could also be an

assumption that regional city councils and economic development boards will be

able to attract enough workers through marketing campaigns which advertise the lifestyle

choices which regional centres such as Mildura are said to offer.

2.70

The committee also notes in the recent World Bank report that the reason

why investment rates in the industry are outstripping the available or

projected labour supply is due to the growth of managed investment schemes in

horticulture. The tax deduction arrangements reduce the relative importance of

the end return on investment when the harvest is finally ready. Prospectus

companies which manage these schemes make a profit by providing development

services like fencing, planting and irrigation.[37]

2.71

The committee believes it is premature to recommend trialling a contract

labour scheme when many first-order issues have not yet been considered and

resolved by the industry and government. The eagerness which is shown for such

a scheme is not matched by a willingness to address what is needed to get it up

and running. The list of practical questions surrounding a pilot contract

labour scheme is endless; for example, are growers willing to contribute to the

cost of implementing a scheme? What criteria will be used to select seasonal

workers? Who will be responsible for recruiting overseas workers? How will

visiting workers interact with local communities? Who will decide where foreign

workers are to be located, for how long and in what numbers? Few in the

industry are able to answer these and other important questions with any

certainty.

2.72

The current difficulties growers have sourcing labour do not, in the

committee's view, pose a serious threat to the economic viability of the

horticultural sector, either now or in the immediate future. The evidence

suggests that the demand for unskilled and experienced seasonal workers is

being met, more or less, by a growing pool of backpackers taking advantage of

relaxed visa requirements under the Working Holiday Makers Scheme. This situation

is likely to continue for the foreseeable future. While the committee accepts

that the flow of overseas backpacker labour could be interrupted by shock waves

from a major terrorist attack or the onset of a global pandemic, it believes

the effects of such events are likely to be short-lived. Evidence from the Bali

terrorist attack shows that the horticultural industry can withstand short-term

fluctuations in the supply of backpacker labour.

Conclusion

2.73

The committee does not believe that anecdotal evidence of labour

shortages indicates an industry-wide labour crisis which would justify an

immediate seasonal contract labour scheme. However, the committee does not

support government policy inaction. Policy is not set in stone. It only awaits

its time, and we do not know when that will be. The concern that the committee

has is that circumstances may force precipitate action by a government

unprepared to deal with them. The committee believes that interim measures are

required to assist the industry plan for a future labour shortage. As discussed

in Chapter 1, pronouncements by the government which categorically reject the

use of unskilled workers from the Pacific region might put the minds of the

public at rest – for we have enough things to debate already - but they are

neither forward-looking nor conducive to policy development.

2.74

Similarly, claims by sections of the union movement that bringing

unskilled seasonal workers in from overseas will 'steal' local jobs, drive down

wages and inevitably create a new class of working poor is an argument which

follows from revelations of 457 visa workers in urban trades. The answer lies

in regulation.

2.75

The committee is concerned that current policy might result in a future

government becoming complacent about the labour needs of the horticultural

sector, especially if the ripple effects of structural change result in labour

shortages becoming a major problem. There is a distinct possibility of this

occurring in the years ahead when growers begin to reap what is currently sowed

by investors. This chapter earlier examined how the horticultural industry is

currently undergoing a major economic restructure as smaller family-owned

businesses slowly (and often reluctantly) give way to large corporate

investors. The committee believes there are signs of an industry-wide trend

toward the corporate end of town parting company with official opposition to

importing unskilled seasonal labour. There is a danger that a future government

might be caught off guard and forced to rush through ill-considered measures to

fill a serious labour shortage, with unforseen consequences.

2.76

The committee understands the basis for current opposition to a seasonal

worker program using foreign labour. It sees no reason, however, for the

proposal to be rejected out of hand, given that labour market forces are apt to

change rapidly. There is a future possibility that acute labour shortages will

require innovative solutions, including a contract labour scheme. The committee

agrees with Peter Mares that there are sound arguments for hastening slowly and

for thinking carefully about how such a scheme should be constructed.[38]

The committee, however, parts company with Mares' added suggestion that a good

starting point would be a pilot scheme that recruits workers from Pacific

nations. While the analysis by Mares is sound up to a point, it ignores an

important step that would need to be made in the process of making policy: how

to proceed from the current policy environment to a point where all necessary

conditions are in place for a pilot scheme to become fully operational,

including practical considerations and political and community support.

2.77

This chapter has addressed the key question on which the debate over a

harvest labour scheme hinges: is there currently a demonstrated industry-wide

shortage of seasonal labour? The committee's short answer is a qualified 'no'.

It believes the immediate priority is for industry and government to establish

what the industry's future labour requirements are likely to be. Then, to maximise

domestic employment opportunities through improved harvest labour wages, before

looking to source unskilled labour from abroad. In view of long-term

demographic projections, this should not preclude work on contingency planning

for the regulation of a foreign contract labour force, for when it is needed.

If such a scheme were to eventuate, as a result of clear necessity, it could

only do so with community and broad political acceptance, which, ironically, is

currently absent except in the regional communities areas which are likely to

be affected.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page