Background

2.1

The terms of reference for this inquiry reflect a proposal for life

insurers to have a greater role in providing rehabilitation and related health

services presently prohibited by the Health Insurance Act 1973. This

proposal was expressed in evidence by various members of the life insurance

industry, particularly the Financial Services Council (FSC).

2.2

In brief, the FSC posited that some Australians experience a gap in

their cover when seeking access to medical treatment in order to recover from

injury and return to work. Observing that this gap has negative repercussions

for the individual, for society, and for the economy more broadly, the FSC

argued that the life insurance industry is well-placed to address this problem

but is currently prevented from doing so. In addition, the FSC indicated that its

proposal would help address concerns about the financial sustainability of the

life insurance industry.

2.3

The FSC's proposal calls for amendments to primary and delegated legislation

that currently prohibit life insurers from providing benefits for worker

rehabilitation in certain circumstances. A representative of the FSC presented

the proposal in a positive light:

It's not every day that you see a convergence of the interests

of customers and private sector providers in relation to a public policy issue

which also contributes positive benefits to the Australian economy through

increased workforce participation and lower government health and welfare

expenditure.[1]

2.4

This chapter outlines the FSC's proposal and puts it in context, as

follows:

-

firstly, the problem that the proposal seeks to address;

-

secondly, the origins of the proposal; and

-

thirdly, the details of the proposal.

The problem that the proposal seeks to address

2.5

Currently, an injured person can receive assistance for medical

treatment from various sources. This includes benefits received under Medicare,

private health insurance, or other schemes such as workers compensation or

travel insurance.[2]

2.6 Despite these possible funding sources, the committee heard evidence

indicating that Australians can experience a gap in their coverage.[3]

This gap can arise in various circumstances, including where the injured

person:

-

has exhausted their Medicare benefits, or Medicare does not cover

the treatment they require;

-

does not have private health insurance, or their private health

insurance does not cover the treatment they require, or they have exhausted

their private health insurance coverage;

-

has exhausted benefits subject to statutory caps applying to

workers compensation or similar schemes; or

-

is unable to access other sources of cover, such as workers

compensation schemes, including because the injury did not take place at work.[4]

2.7

Even where an injured person is covered, it is possible that they will

experience delays in accessing treatment. This could be, for instance, due to

wait times in the public health system.[5]

2.8

The FSC cited research which illustrates that the longer a person spends

away from work, the less likely it is that they will return to work:

If a person is off work for:

-

20 days, the chance of ever getting back to work is 70 per cent;

-

45 days, the chance of ever getting back to work is 50 per cent;

-

70 days, the chance of ever getting back to work is 35 per cent.[6]

2.9

The FSC's Director of Policy and Global Markets,

Mr Allan Hansall, also referred to economic modelling (commissioned

by the FSC and some life insurers) to show how many people experience a gap in

coverage and could benefit from the proposal:

[R]eforms could provide benefits to a pool of up to 10,118

people a year. Of this pool, Cadence [Economics] conservatively estimates that

there are 1,379 people for whom early intervention would be beneficial and cost

effective, potentially rising to 3,600 under the research's high-side scenario.

It is thought an average of 87 people per year could be prevented from becoming

totally and permanently disabled as a result of receiving additional healthcare

intervention paid for by life insurance...Cadence's report estimates early

intervention could improve return to work times by five weeks, from 18 to 13

weeks.[7]

2.10

Mr Hansall told the committee that the FSC supports the proposal because

it is 'the right thing to do for our customers, to make sure that what we do

responds better for them and is more efficient'. However, he also acknowledged

that the proposal would save insurers money, because intervening early and

helping the policyholder return to work may reduce the need for larger payouts

down the track.[8]

2.11

On this latter point, the committee understands that the Australian

Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has identified prudential risks in the

life insurance industry.[9]

While life insurers were profitable between 2009 and 2016, this was primarily

driven by Individual Life Lump Sum business (which includes death cover,

trauma, and total and permanent disability insurance). Life insurers

experienced low returns and material losses in respect of individual disability

income insurance (also known as income protection insurance) and group lump sum

business.[10]

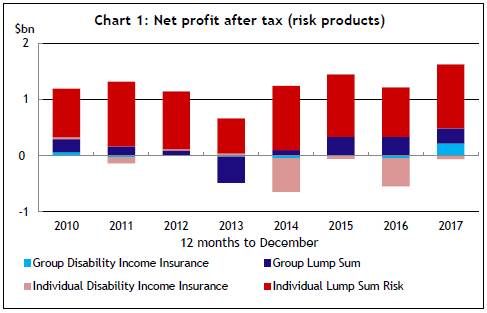

2.12

APRA provided the following chart, which shows life insurers' net profit

after tax in risk products, from 2010 to 2017:

Figure 2.1—Life insurers' net profit after tax in risk

products, 2010 to 2017

Source: Australian Prudential

Regulation Authority, Submission 10, p. 2.

2.13

APRA told the committee that there are a variety of factors driving

these losses, and the sustainability of the industry is an issue that APRA is

continuing to address. However, APRA said that the provision of 'early and

targeted rehabilitation and medical benefits to improve return to work rates

for [disability income insurance] policyholders' could help improve the

sustainability of the industry.[11]

2.14

Indeed, an FSC representative explained that the proposal is partly

intended to assist with the sustainability of the life insurance industry:

For insurers, the reform is also about reducing the cost of

income protection and total-and-permanent disability claims, and making these

policies more sustainable in the longer-term. This is beneficial for customers

and insurers because it reduces cost to the risk pool, which will be

transferred to all customers through cheaper insurance. It is also beneficial

for government and taxpayers because it helps reduce people relying on welfare

benefits.[12]

The origins of the proposal

2.15

The committee recently completed a substantial inquiry into the life

insurance industry.[13]

It presented its final report for that inquiry on the same day that this

inquiry was referred to the committee.[14]

2.16

In the committee's report on the life insurance industry, the Chair,

Mr Steve Irons MP, reflected on the nature of Australia's life

insurance industry:

The life insurance industry is a significant part of the

financial services sector in Australia. It has a noble purpose in providing

financial protection to policyholders in times of need and financial distress.

Despite this, there are sections of the industry that can and must do better in

delivering the protection they promise whilst remaining financially viable long

into the future.[15]

2.17

The committee made a total of 49 recommendations, many of which were

directed either at government or the life insurance industry itself. The committee's

report focussed on areas where 'substantial changes are required to ensure the

life insurance industry is held to account', namely:

-

effective consumer protections and industry codes of practice;

-

the transparency of remuneration, commissions, payments and fees;

-

the provision of advice in the best interests of consumers;

-

group life insurance arrangements that do not disadvantage

certain groups of consumers;

-

appropriate access to personal medical and genetic information;

and

-

fair claims handling practices.[16]

2.18

During the committee's inquiry into the life insurance industry, some

submitters drew attention to restrictions on life insurers' ability to pay

medical expenses and other benefits for worker rehabilitation. The FSC in

particular argued that these restrictions should be lifted, and put a proposal

that resembles the one being considered under the current inquiry.[17]

2.19

In its previous inquiry, the committee acknowledged the importance of

early intervention and measures that support worker rehabilitation. It also

noted that the detail of the FSC's proposal arrived fairly late in the inquiry,

so the committee did not have an opportunity to hear from other witnesses and

submitters about any potential unintended consequences. The committee made the

following recommendation:

The committee recommends that the Australian Government

conduct a thorough inquiry or consultation process before it progresses any

reforms relating to life insurers funding rehabilitation services, including

impacts on private health insurance, or Medicare, and any conflicts of interest

that may arise for an insurer vis-a-vis their customer and the most appropriate

care.[18]

2.20

During this inquiry, FSC representatives were asked whether the FSC was

in conversation with the government about advancing the FSC's proposal.

Mr Hansall of the FSC advised the committee he was not aware of any such

conversations.[19]

2.21

However, the Treasury informed the committee that last year the FSC

wrote to government outlining its proposal at a high level. The government saw

potential benefits and risks to the proposal, as the Treasury told the

committee:

From the government's perspective, it was really a case of:

'Well, this is an interesting issue. We can see that it's a complex issue. We

can see that there may be some gains.' I think the government made a decision

to refer the matter to this committee to see if it could dig up some

submissions and shed some light on more-detailed proposals from the industry in

terms of how it might work and how the regulation might work, given that it's

pretty complex, across life, super and health.[20]

The detail of the proposal

What are the current restrictions

on life insurers?

2.22

Life insurers currently offer a variety of continuous disability

policies. These include total and permanent disability insurance, income

protection insurance for temporary incapacity, and trauma or critical illness

benefits for specified illnesses, conditions or injuries.[21]

2.23

The FSC told the committee that life insurers routinely provide rehabilitation

services under these policies to help claimants recover from injury.[22]

Indeed, the committee understands that many life insurers are investing in in‑house

rehabilitation resources.[23]

2.24

While the current regulatory system allows life insurers to provide some

vocational rehabilitation services, it does not allow them, in certain

circumstances, to pay for medical treatment or therapy that could help

claimants return to work.[24]

As the FSC explained, life insurers are currently not permitted to:

...provide a benefit to a claimant under a continuous

disability policy for treatment costs where either a corresponding Medicare

benefit is payable or where the treatment is a hospital treatment or general

treatment (and is not otherwise excluded from the concept of a health insurance

business).

This restriction applies regardless of whether the Medicare

or Private Health Insurance benefit is exhausted, meaning that any gap in costs

after reimbursement under a private health insurance policy or receipt of a

Medicare benefit will not be able to be paid by the life insurer and will need

to be funded directly by the person receiving the treatment.[25]

2.25

The following table, which was provided by MetLife, distinguishes between

the benefits that, at the moment, life insurers are generally permitted and not

permitted to provide:

Table 2.1—Benefits that life

insurers are currently permitted and not permitted to provide

Benefits that are

generally

permitted |

Benefits that are

generally

not permitted |

| Lump sum payments for

total and permanent disability insurance |

Physiotherapy |

| Income replacement

payments |

Psychiatric treatment |

| Vocational guidance |

Psychological counselling |

| Occupational

rehabilitation |

Funding for surgery |

| Training support |

Any treatment that may be

a Medicare benefit |

| Referral to support

services (such as community based services) |

|

Source: MetLife, Submission

13, pp. 3–4.[26]

2.26

These restrictions are given effect by a range of legislation and subordinate

legislation, including (but not limited to) the:

-

Health Insurance Act 1973, including section 126;

-

Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, including

section 295.460.

-

Life Insurance Act 1995, including sections 9A and 234;

-

Private Health Insurance Act 2007, including

section 121-1;

-

Private Health Insurance (Health Insurance Business) Rules 2018,

including rule 16;

-

Private Health Insurance (Prudential Supervision) Act 2015,

including section 10;

-

Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 including

section 62, and

-

Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Regulations 1994, including

regulation 4.07D.[27]

2.27

The FSC's proposal would reduce these restrictions, and its submission

provided some specific amendments to the above legislation and subordinate

legislation.[28]

How would the proposed system work?

2.28

The committee acknowledges that the proposal has not yet reached a stage

where specific legislative amendments have been drafted in bill form. It also

notes that the proposal has been presented by various members of the life

insurance industry and in various pieces of evidence. Nonetheless, it appears

that the key features of the proposal include the following:

-

In the first instance, an injured person would seek assistance

for rehabilitation from existing sources of cover, such as Medicare, private health

insurance, and workers compensation.[29]

-

A life insurer may provide assistance for a person's

rehabilitation if existing sources of cover are:[30]

-

insufficient (possibly because the relevant treatment is only

partially covered);

-

not immediately available (including 'where waiting times in the

public health system would result in an adverse return to work outcome');[31]

or

-

otherwise unavailable (possibly because the injured person is not

covered or has exhausted their coverage).

-

In cases where existing sources of assistance partially cover the

rehabilitation costs, the life insurer may pay the gap payment. In other cases,

the life insurer may cover the full cost.[32]

-

The injured person would need to hold a continuous disability

insurance policy in order to be offered rehabilitation assistance by a life

insurer.[33]

-

The life insurer would not offer to pay for medical treatments

for every customer. As the FSC stated, payments would be made at the life

insurer's discretion 'if it makes financial sense to do so'.[34]

The committee understands that this may refer to cases where the life insurer

considers that providing rehabilitation assistance would save it money in the

long run (for instance, by assisting an injured person to return to work the

insurer may avoid making larger payouts under income protection insurance down

the track).

-

The proposed payments would not be part of contracts with

customers, and provision of the payments would not appear in product disclosure

statements.[35]

-

Life insurers would be able to provide rehabilitation assistance

to an injured policyholder regardless of whether or not the injury was work‑related.[36]

-

Any assistance offered by a life insurer would be arranged

through the policyholder's treating physician with the policyholder's consent.[37]

However, the life insurer would also 'assess any ideas that are put to them

from the customer in partnership with their medical advisor'.[38]

As an FSC representative explained:

The GP would make the decision

about whether the treatment is appropriate and effective and will return the

person back to work earlier. An insurer will make the decision about whether

they will choose to pay for it.[39]

2.29

Mr Hansall of the FSC emphasised that this proposal 'is not about

life insurers providing private health insurance by the back door or stepping

in the way of existing workers compensation schemes'. Rather, the proposal

intends to provide additional, complementary support where that support would

help with the policyholder's recovery but is not available through other

coverage.[40]

2.30

MLC Life Insurance similarly clarified that the intention is for life

insurers to act as a 'supplementary funder' of medical treatments, which means

that 'any funding would be additive to existing health funding sources in a

limited range of circumstances'. These 'top up' payments would only be made if

both the following criteria are met:

- Where

it can be demonstrated that the planned medical service is reasonable and

necessary to the goal of restoring the customer to health and employment.

- Where

principal healthcare funders are constrained from funding the required services

due to regulation, timing of the availability of treatment (including health

system capacity issues), or, in the case of private health insurance, the

customer is not insured or has exhausted their benefits.[41]

2.31

The FSC also provided four overarching points about how the proposed

policy framework would operate:

- All

treatment the life insurer offers to pay for would be arranged through the

claimant's treating physician with the customer’s consent.

- Life

insurers will not coerce or pressure customers to seek treatment or return to

work.

- Life

insurers will not stop Income Protection (IP) or Total and Permanent Disability

(TPD) insurance payments merely because a customer refuses any treatment that

is offered.

- Decisions

and processes relating to an offer to pay for treatment would be subject to the

usual internal dispute resolution and external dispute resolution processes.[42]

2.32

In conclusion, Mr Hansall of the FSC told the committee that the

life insurance industry would, in consultation with government, 'ensure this

policy is ring-fenced by the proper consumer protections'. He strongly

recommended that any legislation passed to enact the proposal should also

provide for a review to be conducted three or five years after commencement.

The review would consider the effectiveness of the legislation as well as the

conduct of life insurers.[43]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page