Professional and ethical standards

4.1

This chapter discusses the role of industry bodies in addressing the

professional and ethical standards of financial advisers providing personal

advice on Tier 1 financial products. The chapter covers:

-

ethical conduct and codes of ethics;

-

implications for competition and the costs of implementing

professional standards and their regulation;

-

recognition of professional bodies; and

-

implementation of a systems approach and transitional

arrangements.

Ethical conduct and codes of ethics

4.2

During the inquiry the committee considered evidence which suggested

that the financial advice industry should apply a more uniform approach to

adopting codes of ethics. It is the committee's view that ethical conduct is

best assured by a culture that is ethical. To this end, the committee has

considered evidence about the efficacy of codes of ethics and in this section,

discusses the function of codes of ethics, their current status, and proposals

for change.

4.3

Codes of ethics and codes of conduct are different but can be

complimentary to each other:

Codes of conduct are designed to anticipate and prevent

certain specific types of behavior; e.g. conflict of interest, self-dealing,

bribery, and inappropriate actions

...ethics codes can focus...on actions that result in doing the

right things for the right reasons. Ethical behavior should become a habit and

effective codes allow both bureaucrats and elected officials to test their

actions against expected standards. Repeated over time this kind of habit

becomes inculcated in the individual and ingrained in the organization.[1]

4.4

Codes of ethics include both a set of requirements and the commitment of

the members of the occupation or organisation to conform to, and uphold the

rules and ideals.[2]

Codes of ethics often include a set of guiding principles such as the 22

principles set out by Professions Australia who suggest that:

A professional organisation’s standards for entry should also

include a requirement to adhere to an enforceable code of ethics, the requirement to commit to measurable

ongoing professional development and sanctions for conduct that falls below the

required standards.[3]

4.5

The PSC identifies ethics as a core part of professionalism which in its

view comprises the personally

held beliefs about one’s own behaviour as a professional. It’s often linked to

the upholding of the principles, laws, ethics and conventions of a profession

as a way of practice.[4]

4.6

Professions Australia's definition of a profession includes codes of

ethics:

It is inherent in the definition of a profession that a code

of ethics governs the activities of each profession. Such codes require

behaviour and practice beyond the personal moral obligations of an individual.

They define and demand high standards of behaviour in respect to the services

provided to the public and in dealing with professional colleagues. Further,

these codes are enforced by the profession and are acknowledged and accepted by

the community.[5]

Current status of codes of ethics

in the financial advice industry

4.7

Dr George Gilligan has argued that a focus on increasing the professionalisation

can make an important contribution to restoring protection for consumers:

There is an imbalance between the privileged participation

and potential for rewards as licensed financial services actors that

individuals and organisations receive, in comparison to the civic duties and

obligations that could or should accompany that privileged status.

Balance can only be restored through normative change at individual,

organisational and industry levels. An emphasis on culture and increased

professionalisation can be a fruitful pathway to reinvigorate the implied

social contract between financial organisations and the financial citizenry, from

whom increasing sophistication is expected by both the state and the industry,

notwithstanding evidence that many citizens have substantial difficulty in

understanding those risks.[6]

4.8

ASIC advised the committee that it considers that the financial advice

industry has a significant amount of work to do to improve the culture of

financial advisers, and to move from operating as a sales-based culture to a

profession exercising independent judgement in the best interests of their

clients.[7]

The current regulatory framework imposes obligations on the AFS licensee or

authorised representative, rather than the individual financial adviser.[8]

4.9

ASIC suggested that the large number of industry associations

operating in the financial advice industry presents some challenges to

achieving a harmonised set of codes. They also noted that there is an increased

system cost when multiple administration and compliance systems for multiple

codes are operating across these industry associations.[9]

4.10

The Superannuation Consumers' Centre submitted that codes of practice are

one of the two main tools of self-regulation, the other being complaints

schemes. They also submitted that while the complaints schemes have been more

successful, this was because there was a requirement to belong to an ASIC

approved complaint scheme unlike other codes that are not currently mandatory. [10]

4.11

Some industry bodies with members operating in the financial advice

industry have codes of ethics. The Accounting Professional & Ethical

Standards Boards has published its Australian Professional & Ethical

Standard 110 Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants.[11]

The FPA has had a code of ethics since 1992 and proposed that a code of ethics

should be required for the recognition of professional bodies.[12]

4.12

ASIC advised the committee that while some financial advisers

adhere to a code of ethics as part of membership of an industry association or

as part of a professional designation, it is not compulsory to belong to an

industry association, nor is it clear to what extent the codes are followed,

investigated and enforced.[13]

Implications of adopting codes of ethics

4.13

Some submitters supported the requirement for financial advisers to be

members of an approved professional association and to adhere to professional codes

of ethics.[14]

The committee notes however that this is not a universally held view. Submitters

who did not support a mandatory code of ethics did so on the basis that they

considered codes to be unnecessary.[15]

4.14

The FPA advised the committee that some evidence exists to show that

financial advisers who operate under a professional association are less likely

to be the subject of ASIC enforcement actions in relation to financial advice.[16]

Implications for costs and competition

4.15

ASIC informed the committee that in its view, costs to industry may

include:

-

developing the code;

-

complying with additional obligations that go beyond those

imposed under the law; and

-

funding independent code administration, including:

-

implementing dispute resolution procedures, remedies and

sanctions;

-

monitoring and reporting on compliance; and

-

regular independent reviews.[17]

4.16

ASIC also advised that competition among industry bodies for members

actually means that the existing industry bodies have a disincentive to levy

their members for sufficient funds to investigate and regulate for compliance

with codes, particularly when such codes are not mandatory.[18]

4.17

The FPA informed the committee that the cost for membership of

professional associations range from a few hundred dollars to $1000 annually. The

FPA noted that professional bodies may incur costs associated with ensuring

compliance with standards and these are generally included in membership fees.[19]

Costs relative to benefits of professionalisation

4.18

Implementing codes of ethics can be seen as part of a broader approach

to professionalisation of the financial advice industry. SPAA acknowledged that

there are costs associated with professionalisation but suggested that the

benefits far outweigh the costs involved.[20]

The FPA argued that adherence to professional and ethical obligations must not

be viewed as a cost burden:

This is an essential business investment as the cost of not

taking action to improve standards will be far greater. The cost of not acting

to change the status quo will be borne more heavily by consumers than the

monetary investment industry must make to lift the bar.[21]

4.19

From its survey of industry participants, the PSC found that there is

industry support for professionalisation:

Despite recognising that there are significant costs

associated with professionalisation, all of the industry stakeholders

interviewed were in favour of it. Indeed, all of the interview respondents were

confident that the benefit of professionalisation outweighs the cost and

transition effort required to achieve it. Of the stakeholders interviewed,

association groups, who are aspiring to embark on professionalisation, were

most concerned about the cost. Despite this they all agreed that the benefits

outweighed the costs.[22]

4.20

The PSC reported that results from its survey indicate that industry

participants believe that the benefits of professionalisation outweigh the

costs including increased community protection, less regulation, higher

standards, increased trust in professionals and financial benefits to

individual professionals.[23]

The survey also indicated that there is a general expectation among the

industry stakeholders that professionalisation will eventually lead to reduced

regulation in the industry.[24]

4.21

It was argued that the cost of regulation to industry participants

should be balanced against the broader cost that a lack of professional

regulation represents to consumers.[25]

The committee notes that previous inquiries have heard that the cost of poor

financial advice may be as high as $37 billion over the last decade[26]

and so the cost of developing and regulating codes of ethics should be balanced

against the risks associated with poor standards and inappropriate advice.

4.22

The ABA advised that the inevitable compliance costs associated with

establishing and maintaining any new framework can be offset by productivity

and efficiency gains such as the portability of qualifications, as well as

deregulation projects, especially changes intended to reduce the compliance

costs of disclosure standards.[27]

4.23

In the FPA's view the associated costs would not be high and were in the

interests of members of the industry as a way of maintaining a competitive

advantage:

It is also important to consider the impact of raising

education standards and requiring the adoption of professional obligations on

competition in the financial advice market. The FPA believes this will be

negligible. This Inquiry is taking place in an environment where financial

advice providers themselves are currently competing to lift standards within

their own businesses.[28]

4.24

The Consumer Credit Legal Service WA submitted that in their view

regulating the professional and ethical behaviour of financial advisers should

result in fairer competition in the industry over the longer term:

It would potentially act as an additional disincentive for

financial advisers who may engage in misconduct for their own financial

benefit. This, in turn, may limit the participation of ‘rogue’ financial

advisers in the industry. Ultimately, financial advisers who already hold

themselves to higher professional and ethical standards are likely to remain

more competitive as the playing field is levelled.[29]

4.25

The PSC informed the committee that the impact on competition can depend

on whether the changes are industry wide or whether part of the industry is

targeted:

This is the challenge that emerges in education: introducing

wholesale, industrywide change just tends to lead to a massive flight to the

bottom and increased competition in providers. This is why our particular

regime is about picking and nurturing the culture of professions. It is not

necessarily about trying to professionalise an entire industry, but about

picking communities that will benefit and respond to it more strongly, and I

think our systems of regulation need to find a way to encourage that.[30]

4.26

Other submitters suggested that the financial advice industry is already

highly regulated with current requirements leading to a rising cost of advice. Some

submitters suggested that this is leading to ongoing consolidation in the

advice industry, where many independent licensees are finding they can no

longer sustain the high cost of compliance.[31]

Committee view

4.27

The committee observes that requiring adherence to a code of ethics through

membership of a professional association may put some cost pressure on industry

participants. From the evidence received in this inquiry, industry participants

generally acknowledge that those resulting cost and competition pressures are

outweighed by the benefits of adopting codes of ethics to enhance professional

and ethical standards.

4.28

As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, codes of ethics seek to

bring about the desired behaviour for the right, self-motivated reasons (as

opposed to behaviour motivated by fear of sanction). The committee considers

that adoption and implementation of codes of ethics would help to move the

financial advice industry towards a resilient professional culture that would

lead to consistent ethical behaviour.

4.29

The PSC requires professional associations and their members to have

certain processes, programs and practices in place before a Professional

Standards Scheme can be approved. The requirements are discussed in more detail

in the next section. However, the committee notes here that one of the

requirements relates to ethics which are described as:

The prescribed professional and ethical standards clients can

rightfully expect your members to exhibit. This includes your specific

expectations of practice and conduct, and should do more than just reiterate

statutory expectations.[32]

4.30

To assist professional associations the PSC has published a Model

Code of Ethical Principles, that sets out the nature and role of codes of

ethics, a description of the generic content of codes of ethics, and an outline

of the processes for devising a code of ethics.

4.31

The committee's view is that there needs to be a change in the drivers

of behaviour in the financial advice industry. While acknowledging that there

are many financial advisers who operate to very high ethical standards, the

committee considers that for far too long, there has been a significant

minority of financial advisers being driven by self-interest. It is the

committee's view that professional ethics should be a driver of the behaviour

of financial advisers.

4.32

The committee therefore recommends a new benchmark, that professional

associations be required to establish codes of ethics which are compliant with

the requirements of a Professional Standards Scheme under the Professional

Standards Council. Under the recommended model, every financial adviser will

have to be a member of a professional association that is approved by the PSC,

which means that they will be working under the auspices of at least one

compliant code of ethics.

Recommendation 11

4.33

The committee recommends that professional associations representing

individuals in the financial services industry be required to establish codes

of ethics that are compliant with the requirements of a Professional Standards

Scheme and that are approved by the Professional Standards Council.

Recognition of professional associations

4.34

In this section, the committee discusses the recognition of industry

associations, including options for approaches to recognition, such as the

Professional Standards Schemes through the Professional Standards Councils. As

in other chapters, the committee's discussion focusses on financial advisers

providing personal advice on Tier 1 financial products.

Options for recognition

4.35

Recognition of industry associations would be required if membership of

an industry association is contingent on an individual being permitted to

operate as a financial adviser. The AFA submitted that some vehicle to

recognise professional associations has merit if membership of professional

bodies is mandated.[33]

4.36

ASIC informed the committee that in its view, a recognised professional

body could perform the role of a professional standards body to increase

professionalism in the financial advice industry. ASIC noted that options for

recognising such a body include recognition by:

-

ASIC; or

-

the Australian Government in regulations; or

-

Parliament through legislation; or

-

a specially created advisory panel.

4.37

If the power to recognise professional bodies is given to ASIC, ASIC

advises that there should be a clear statutory purpose for the power by reference

to clear statutory criteria. ASIC also indicated that the criteria for

recognition should depend on the purpose of the recognition. [34]

4.38

The AFA was not convinced of the need for financial advice professional

associations to be recognised by ASIC. However, should government consider it

necessary, the AFA suggests that accreditation of professional associations and

clear criteria would be required.[35]

4.39

The FPA proposed that a co-regulatory framework for recognition of

professional bodies should include legislative structure, professional body

criteria, a practising certificate, and restricting the use of the titles 'financial

planner' and 'financial adviser'. The FPA submitted that:

We also considered the role of a profession and the link to

the notion of serving the ‘public interest’, whereby professionals are

considered public servants, whose duty to the public and the community takes

precedence over deriving client or private benefit. This must be a key

consideration in the development of appropriate criteria for a Regulator or

government body to recognise a professional body – serving the ‘public

interest’.[36]

4.40

Many submitters did not support recognition of professional bodies being

undertaken by ASIC.[37]

In FINSIA's view, such a role would be outside ASIC's legislative objectives

and scope. FINSIA suggested that an independent advisory board would be more

appropriate.[38]

The Financial Services Council also suggested recognition by a separate board

or body.[39]

4.41

The Superannuation Consumers' Centre strongly supported professional

bodies as part of the pathway to professionalism, but had concerns about

approval of industry bodies by ASIC:

We think it would be very confusing for consumers, because

industry associations have roles that go well beyond competency and

professional standards. They are effectively a form of

union for their members. They advocate for their members' interests and often

vigorously and publicly oppose efforts of the regulator, including to raise

standards, as we saw quite recently when ASIC tried to raise standards of RG

146.[40]

Professional Standards Councils

4.42

In this section the committee considers whether the PSC would provide an

appropriate body and process to recognise professional associations.

4.43

The PSC is the combined Australian Governments' statutory body

responsible for the approval, monitoring and enforcing of Professional

Standards Schemes. The PSC's goal is to protect consumers by demanding

high levels of professional standards and practice from those professionals who

participate in Professional Standards Schemes.[41]

The PSC informed the committee that:

The three essential goals of professional standards

legislation are to protect consumers, improve professional standards, and

thirdly, and perhaps most uniquely...to encourage and, where appropriate, assist

the self-regulatory capacity of professional communities so that they can take

greater responsibility for consumer protection. We do this by working with

associations to strengthen and improve professionalism, and provide

self-regulation while protecting consumers. In return for these commitments to

greater professional accountability, professionals that take part in approved

Professional Standards Schemes have their civil liability limited under law.[42]

4.44

Professional Standards Schemes are legal instruments that bind

associations to monitor, enforce and improve the professional standards of

their members, and protect consumers of professional services. Professional

Standards Schemes also cap the civil liability or damages that professionals

who take part in an association’s scheme may be required to pay if a court

upholds a claim against them.[43]

4.45

Professional Standards Schemes aim to provide the following benefits to

consumers:

-

their service providers have formal professional standards they

must uphold;

-

creates a body of professionals to make sure their service

provider upholds professional standards; and

-

if anything does go wrong, there are insurance or assets

available to pay damages awarded by the court.[44]

4.46

For an industry association to participate in a Professional Standards

Scheme, there is an intensive application process. The association must fall

within the definition of an 'occupation association' as set out in the

professional standards legislation and have programs and practices in place for

each of the following areas:

- Education: Specific technical and professional

requirements to practice in the professional area, including entry-level formal

qualifications, certification, and ongoing continuing professional development

and education.

- Ethics: The

prescribed professional and ethical standards clients can rightfully expect

members to exhibit. This includes specific expectations of practice and

conduct, and should do more than just reiterate statutory expectations.

- Experience: The personal capabilities and experience

required to practice as a professional in the professional area.

- Examination: The mechanism by which all of the elements

above are assessed and assured to the community. This extends beyond

qualification or certification requirements into expectations of regular

assurance of practice, such as compliance programs and professional audits.

- Entity: The association must be an entity capable of

overseeing and administering professional entry, professional standards, and

compliance expectations on behalf of the community.[45]

4.47

The PSC informed the committee that at present the Institute of Public

Accountants, the Institute of Chartered Accountants and CPA Australia are the

only bodies that operate across financial services that are regulated through

the PSC. Other organisations less directly connected to financial

services such as the law societies in each state and territory are also

regulated by the PSC.[46]

4.48

The AFA informed the committee that in its view Professional Standards

Schemes are broader than recognition, noting that approval of a Professional

Standards Scheme also includes the establishment of a limit on civil liability.

The AFA indicated that:

This invariably involves a significant workload with respect

to professional indemnity insurance, historical insurance claims and actuarial

considerations. There are some significant implications with respect to the

financial advice profession that would need to be addressed before this was

considered, including the implications of such a scheme in the context of the

Corporations Act and the role of licensees, who under the Corporations Act are

liable for consumer claims.[47]

4.49

The FPA submitted that professional bodies should be recognised by the

PSC and noted that the PSC scheme is a successful cooperative federal and state

government initiative for the public regulation of professions through

individual professional membership.[48]

4.50

The AFA indicated to the committee that it considered that:

The Professional Standards Council presents a vehicle for the

formal recognition of professional associations through regulatory means. The

application process through the Professional Standards Council is rigorous and

comprehensive. The Professional Standards Council identifies the key elements

that would typically be expected of a profession.

We believe that further consideration of the option and the

criteria set out by the Professional Standards Council is appropriate.[49]

Committee view

4.51

The committee considers that requiring professional associations to

establish Professional Standards Schemes approved by the Professional Services

Councils has a number of advantages including that:

-

the PSC is an existing body, so no new body would be created;

-

Professional Standards Schemes are an established process that

has been implemented in other sectors; and

-

three industry associations whose members provide financial

advice are already covered by Professional Standards Schemes.

4.52

The committee therefore recommends that financial advice industry

associations that wish to have representation on the Finance Professionals'

Education Council and to be able to make recommendations to ASIC regarding the

registration of financial advisers, should be required to establish

Professional Standards Schemes under the Professional Standards Councils. In

making this recommendation the committee notes that:

-

additional resources may be required by the PSC in order to make

appropriate arrangements for implementation and transitional considerations;

and

-

the government may need to consider the interactions between

liability arrangements under Professional Standards Schemes and the Corporations

Act 2001.

Recommendation 12

4.53

The committee recommends that financial sector professional

associations that wish to have representation on the Finance Professionals'

Education Council and to be able to make recommendations to ASIC regarding the

registration of financial advisers, should be required to establish

Professional Standards Schemes under the Professional Standards Councils, within

three years.

4.54

As is currently the case, financial advisers should be free to choose to

join multiple associations, including those industry bodies without a

Professional Standards Scheme. The committee considers, however, that as

outlined in earlier recommendations of this report, a person must be required

to join a professional body that is operating under a Professional Standards

Scheme approved by the Professional Standards Councils in order to be registered

as a financial adviser. That professional association will then become the body

that is authorised to advise ASIC regarding the fitness of the person to be

registered, subject to completion of the professional year and registration

exam. That professional association would also advise ASIC on the continuing

fitness for registration of an individual based on achievement of mandatory CPD

and compliance with the code of ethics.

4.55

If a financial adviser wishes to change professional sectors and have a

different association as the nominated body to oversee professional and

educational standards, they must meet the professional year (with recognised

prior learning provisions) and registration exam requirements for that body and

not have any censures or limitations outstanding from the previous professional

association or ASIC.

Recommendation 13

4.56

The committee recommends that any individual wishing to provide financial

advice be required to be a member of a professional body that is operating

under a Professional Standards Scheme approved by the Professional Standards

Councils and to meet their educational, professional year and registration exam

requirements.

Implementation of measures to raise professional, ethical and education

standards in the financial advice industry

4.57

In this section the committee sets out its views on the implementation

of the recommendations in this report. The section also discusses the need to

take a systems approach and to address transitional arrangements.

Committee view on a systems

approach

4.58

While the committee notes the important role of high professional and

ethical standards, the committee recognises that lifting professional and

ethical standards is only part of a more complex system. All parts of the

system need to be operating effectively to provide appropriate safeguards for

consumers and investors while allowing efficiency, innovation and growth within

the industry. As noted in Chapter 1, Professor Reason's model suggests that appropriate

organisational or systems defences are required to reduce risk, which in the

case of financial advice includes the measures outlined in para 1.55. The

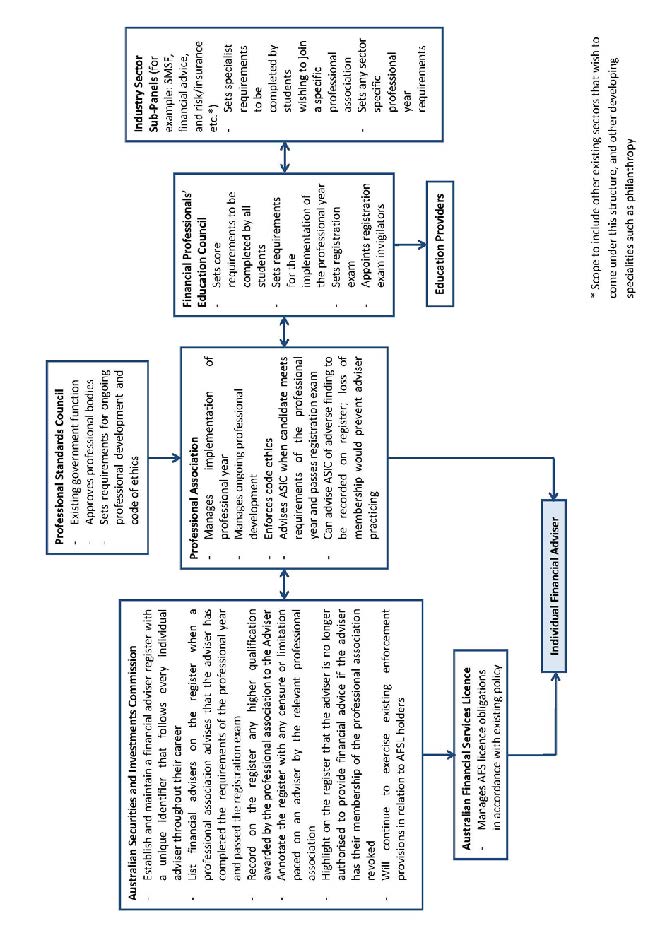

committee is therefore proposing the approach set out in Figure 5.1, which brings

together recommendations from this inquiry. The figure demonstrates:

-

the role of professional associations;

-

professional and ethical standards and their oversight by the PSC

as recommended in this Chapter;

-

ASIC's role in establishing and managing the register of

financial advisers as already announced by the government with the changes

recommended in Chapter 2;

-

the role of AFS licensees in managing license obligations;

-

the Financial Professionals' Education Council and its industry

sub-sector panels as recommended in Chapter 3;

-

education providers; and

-

individual financial advisers.

Figure 5.1: Financial advice education stakeholder

relationships

4.59

Figure 5.1 includes the following criteria and information for financial

advisers to be on the register that the committee recommended in Chapter 2:

-

a unique identifier that follows every individual adviser

throughout their career;

-

listing financial advisers on the register when a professional body

advises that the adviser has completed the requirements of the professional

year and passed the registration exam;

-

a record of any higher qualification awarded by a professional

body to the adviser;

-

an annotation with any censure or limitation placed on a

financial adviser by professional body; and

-

highlighting on the register when an adviser is no longer authorised

to provide financial advice if the adviser has their membership of the professional

body is revoked.

4.60

The committee notes that its recommended approach:

-

creates no new government or regulatory entities;

-

expands the membership and function of an existing industry led

and funded council that sets educational standards;

-

should not increase the cost of advice to consumers as the cost

of running the council (currently less than $50 000) will be spread across

multiple associations;

-

complements measures already announced by government, including

the register of advisers;

-

addresses the key concerns of most stakeholders identified during

the inquiry;

-

draws from existing practices in other professions such as law,

health and accounting; and

-

draws on the assessment concept adopted by regulators in other

sectors, of having both a theory exam (centrally controlled but independently

administered by approved invigilators) as well as an assessment of demonstrated

competence including the potential for recognition of prior learning in some

areas.

4.61

The approach recommended above would help address the PSC requirements

that for an industry association to participate in a Professional Standards

Scheme, they must have programs and practices in place related to education,

ethics, recognition of professional experience and use practical assessments

and examinations to test competence and knowledge. In addition, they must have

the capacity to oversee and administer professional entry, professional standards,

and compliance expectations on behalf of the community.

Committee view on transitional

arrangements

4.62

The committee notes that with any significant policy or legislative

change, appropriate time is required for industry and consumers to implement

new requirements. While the committee has received evidence in submissions and

hearings about transitional arrangements, the committee has not examined

transitional issues and proposals in detail. The committee does note, however, that

some of the recommended changes will require different transitional timeframes.

4.63

The establishment of the register of financial advisers may occur sooner

than industry associations are able to establish approved Professional

Standards Schemes under the Professional Standards Councils. The committee also

notes that varied transitional arrangements may be needed for financial

advisers who are at different stages of their career.

4.64

In framing its recommendations, the committee has been mindful of the

need for transitional arrangements. The committee is however firmly of the view

that swift and decisive action is required in order to raise the professional,

ethical and education standards of financial advisers. On this basis, the

committee is recommending that the government require implementation of these

reforms within three years of response to this report. The Finance

Professionals' Education Council should be established within six months, as it

will have a key role as the body that will determine recognised prior learning

requirements for existing advisors. The establishment of a code of ethics compliant

with Professional Standards Scheme guidelines should be finalised within 18 months.

Recommendation 14

4.65

The committee recommends that government require implementation of the

recommendations in accordance with the transitional schedule outlined in the

table below.

|

Transitional arrangement

and timeframes

|

Date

|

|

Provisional registration

(available to existing financial advisers from the implementation of the

proposed government register until 1 Jan 2019 to address the goal of

transparency)

|

Mar 2015

|

|

Finance Professionals’

Education Council established

|

1 Jul 2015

|

|

FPEC releases AQF-7

education standards for core and professional stream subjects

|

Jun 2016

|

|

Establishment of codes of ethics

compliant with Professional Standards Scheme guidelines

|

Jul 2016

|

|

FPEC approved AQF-7 Courses

available to commence

|

Jan 2017

|

|

FPEC releases recognised

prior learning framework (dealing with existing advisers and undergraduates

who commence AQF-7 courses prior to Feb 2017)

|

Jul 2016

|

|

FPEC releases professional

year requirements including recognised prior learning framework for existing

advisers

|

Jul 2016

|

|

Professional associations

operating under PSC Professional Standards Schemes

|

1 Jan 2017

|

|

Target date for existing

financial advisers to qualify for full registration

|

1 Jan 2018

|

|

Cut-off date for full

registration - provisional registration no longer available

|

1 Jan 2019

|

Senator David Fawcett

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page