Chapter 15

Civil–military coordination

15.1

In this chapter, the committee focuses on the notion of civil–military

cooperation (CIMIC). It identifies where the military and civilian sectors are

working well together; where there are impediments to effective coordination;

and how they could be reduced or removed.

15.2

The committee has placed a greater emphasis on CIMIC rather than the

broader government and non-government sector because most of the evidence before

the committee discussed issues of coordination and cooperation through a CIMIC

paradigm. The committee understands that, historically, the military has been

the major contributor to peacekeeping and that many of the models that are used

in a peacekeeping setting derive from military culture. The committee is

mindful that examining issues of coordination and cooperation through the

concept of CIMIC does not facilitate a discussion of alternative approaches. It

does, however, allow the committee to analyse in detail an important aspect of the

relationship between the government and non-government sectors in a

peacekeeping operation.

15.3

The concepts of civil–military cooperation and coordination

have received increased attention in recent years. At the international level,

the UN's civil–military coordination (CMCoord) doctrine focuses on

facilitating the humanitarian mission in a militarised environment and creating

mutual understanding between the military and civilian components of an

operation.[1]

The concept of humanitarian civil–military coordination used by the

Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC)[2]

is consistent with that used by the UN Civil–Military Coordination Section. It

defines this concept as:

The essential dialogue and interaction between civilian and

military actors in humanitarian emergencies that is necessary to protect and

promote humanitarian principles, avoid competition, minimize inconsistency, and

when appropriate pursue common goals. Basic strategies range from coexistence

to cooperation. Coordination is a shared responsibility facilitated by liaison

and common training.[3]

15.4

In contrast to the UN CMCoord, which emphasises 'shared responsibility',

civil–military cooperation (CIMIC) tends to look at cooperation from a military

perspective.

Importance of CIMIC

15.5

Although the military and civilian components of a peacekeeping

operation have been working side by side for many years, the increasing levels

of interaction between them have underlined the significance of civil–military

coordination. The growing awareness of the importance of coordination has

produced a body of thought, which is still evolving, on CIMIC. The central

concern of CIMIC is with establishing and maintaining a constructive

relationship between the military and civilian sectors.

15.6

CIMIC is often referred to as a 'force multiplier', but there are a

number of significant difficulties in achieving effective coordination.[4]

The UN civil–military officer field handbook notes that problems with

coordination extend to, among other things, security, medical evacuation,

logistics, transport, communications and information management. It states

further:

The challenges include such issues as ensuring that

humanitarians have the access they require, but at the same time do not become

a target. Other challenges include minimizing the competition for scarce

resources such as ports, supply routes, airfields and other logistic

infrastructure.[5]

15.7

The failure to establish effective and appropriate civil–military

relations not only creates inefficiencies but can also have more serious

consequences for the mission.[6]

Thus, in complex missions, militaries need to be able to do more than just

generate combat power. To avoid duplication of efforts, prevent wasting energy

and resources, and to promote the safety and wellbeing of all, both military

and humanitarian workers need to ensure that their activities are

complementary. The committee now examines the ADF's approach to CIMIC.

Defence CIMIC Doctrine

15.8

The Department of Defence recognised that the military 'seldom brings

success in its own right'. It acknowledged the importance of coordinating

activities with humanitarian aid agencies, including AusAID and NGOs:

Such planning can ensure military efforts do not cut across

carefully planned NGO campaigns. Conversely uncoordinated NGOs' goals and

actions can unwittingly contribute to a conflict or compromise the desired

security of a mission.[7]

15.9

Defence has formulated its own Defence Civil–Military Cooperation

Doctrine and procedures. These are designed to assist in planning and

implementing ADF missions within the wider civilian context. Defence is of the

view that the current procedures, which focus on role definition, planning and

consultation, meet its objectives for peacekeeping operations. It acknowledged,

however, that 'to the extent that these procedures can produce greater

cooperation in mutually securing respective ADF and civilian goals, there may

be some benefit in further alignment with UN procedures'.[8]

15.10

Major General Ford explained that the term 'civil–military cooperation'

developed from a military background. He noted that it has been 'seen as the

way the military gets other organisations to work with it' and how it makes

sure that NGOs 'do not interfere' with military operations.[9]

Even so, in his view, ADF CIMIC doctrine tended to be more encompassing in

reality:

Certainly we still run CIMIC [cooperation] courses in the

Australian Defence Force rather than civil–military coordination courses.

Having said that...generally the discussion is much more integrated than the name

and the background of that term ‘CIMIC’ suggests.[10]

15.11

Even so, according to Major General Smith, Austcare, there is a difference

in approaches to CIMIC. For example, in the view of NGOs, ADF's approach to

CIMIC tends to be: ‘How can we work with civilian agencies to achieve our

military mission?’ He explained that the UN focus is on 'civil–military

coordination rather than on cooperation'. He suggested that while there may

only be a name difference, 'the definition is very different'.[11]

15.12

AusAID considered that, while reflecting different perspectives, both

the UN and the ADF approaches to civil–military interaction were appropriate:

In essence, the UN doctrine approaches CIMIC from the civilian

direction while the ADF approaches CIMIC from the military side. Both are

complementary and allow for each group to establish operating arrangements

(from coexistence to cooperation) appropriate to the entire range of hostile,

potentially hostile, or stable environments encountered.[12]

15.13

Nonetheless, while recognising the importance of the ADF aligning its

activity with its military mission, AusAID also noted that the ADF should

remain cognisant of the broader picture in order to provide NGOs with 'the

space and independence they need to operate'.[13]

It stated further that, 'More gains could be made in terms of joint conceptualisation,

joint planning and joint preparations, including work on joint doctrine or

policy'.[14]

In the context of 'continuous improvement', it was of the view that there was

room for improvement in 'closer doctrine and policy settings and in recognising

the separate but overlapping contributions' by both sectors.[15]

15.14

World Vision Australia observed that ADF's processes in developing its

approach to CIMIC had been inclusive:

...as the ADF were developing their policy for civil–military

engagement, engagement with NGOs over the development of that policy seemed

crucial to them and it seemed crucial to us as well, because it gave us both a

better understanding of the space in which we work and how we can operate more

effectively in the field.[16]

15.15

ACFID also reported a good relationship with the ADF in relation to

CIMIC functions.[17]

15.16

In contrast, Austcare expressed concern about the appropriateness of the

ADF's approach to CIMIC. It argued that the Defence CIMIC doctrine is focussed

on the ADF's role and ensuring that civil–military relations facilitate the ADF

missions.[18]

In its view, the ADF needs to go further:

...and be prepared to share and adjust its doctrine to accommodate

the views of key civilian agencies, or risk criticism of being unable to

reflect civilian requirements. The adoption of CMCoord doctrine would obviate

this dilemma.[19]

15.17

It recommended that the ADF and the AFP align their CIMIC doctrine and

procedures with those of the UN, 'thereby ensuring a uniform standard based on

UN experience'.[20]

Committee view

15.18

The committee recognises that the failure to establish effective and

appropriate civil–military relations not only creates inefficiencies but can

have more serious consequences for missions.[21]

The ADF has developed a CIMIC doctrine to assist it to plan and implement ADF

missions in the wider civilian context. A number of NGOs reported that the

ADF's approach to CIMIC was appropriate. AusAID agreed but was of the view that

'in the context of continuous improvement', there was scope for improvement.

Defence indicated that there may be some benefit in further aligning their

doctrine with UN procedures to achieve greater cooperation between ADF and NGOs

in meeting their respective objectives. Austcare went further to suggest that

the ADF should adjust its CIMIC doctrine to accommodate civilian requirements. In

light of the evolving nature of CIMIC and the suggestion that ADF's doctrine

could be improved, the committee believes that an ADF review of its CIMIC doctrine

would be timely.

Recommendation 15

15.19

The committee recommends that, in consultation with

AusAID and ACFID, Defence review its civil–military cooperation doctrine,

giving consideration to identifying measures to improve coordination between

the ADF and the NGO sector when engaged in peacekeeping activities.

15.20

The committee recommends further that Defence

include a discussion on its CIMIC doctrine in the upcoming Defence White Paper

as well as provide an account of the progress made in developing the doctrine

and its CIMIC capability in its annual report.

15.21

It should be noted that the AFP now forms an important part of the

security contingent in complex peacekeeping operations, and its relations with

NGOs are important. Professor Raymond Apthorpe and Mr Jacob Townsend commented

that it 'might be worth attempting to lead a progressive conceptual shift from

CIMIC (civil–military cooperation) to CIMPIC (civil–military–police

cooperation)'.[22]

Both the AFP and AusAID saw merits in this proposal, though they were concerned

that recognition must be given to the different roles of these groups and any

such doctrine should not compromise their core functions.[23]

The committee also sees value in this proposal to consider the police component

in developing CIMIC doctrine.

Recommendation 16

15.22

As part of this review process, the committee

recommends that, in consultation with AusAID and other relevant government

agencies and ACFID, Defence and the AFP consider the merits of a

civil–military–police cooperation doctrine. The consideration given to this

doctrine would be reflected in the committee's proposed white

paper on peacekeeping.

15.23

A most important factor when considering CIMIC doctrine is how well it

works in practice. In developing and implementing its CIMIC doctrine, the ADF

and government as a whole should start by looking at the early stages of a

peacekeeping operation.

Planning at pre-deployment level

15.24

As noted previously, NGOs remain largely outside the formal structure

for conceiving and planning peacekeeping operations. There is no standing or

formal whole-of-government mechanism for government agencies and NGOs to

consult at the strategic planning phase. The UN CMCoord states quite clearly

that 'to ensure all issues are given adequate attention and to facilitate

timely direction, coordination should take place at the highest possible

level'.[24]

Some witnesses were critical of the lack of planning between government and

NGOs at this strategic level.

15.25

Major General Smith, Austcare, was of the view that 'it is too late to

commit to an operation and then expect NGOs to magically fit into whatever

template' might have been decided. He argued that 'The earlier that representatives

of NGOs can be brought into this planning process, the better it will be'. For

example, based on his own experience as an ADF peacekeeper in East Timor, he

considered that INTERFET would have benefited from better coordinated planning:

The mistake that I made—and it was a total lack of training and

understanding—was in relation to the humanitarian dimension of that operation.

There was a clause in the mandate that said that INTERFET would conduct

humanitarian operations within force capabilities. Had I been educated about

the way the UN works, I would have immediately organised with the incoming

humanitarian coordinator being deployed to East Timor to arrive in Australia

for discussions with General Peter Cosgrove to ensure that the humanitarian

plan had been sorted out in advance. As it was, it took 10 days on the ground

before the humanitarian coordinator and the INTERFET commander actually got

their humanitarian plans in sync. They were actually very, very divergent. That

is an example of the sort of cooperation that I think needs to go on in

planning and preparation.[25]

15.26

He advised the committee that he was unaware of any current mechanism,

'where the NGO community, AusAID and Defence come together in any type of

planning way for any of these crises.' In his view, the situation should be

addressed.[26]

Overall, Austcare noted that more needed to be done to improve Australia's

'whole-of-nation' effectiveness. It stated that post-mission reports have

'repeatedly indicated a failure of adequate civil–military preparation and

planning'.[27]

Austcare suggested that AusAID take a greater role in facilitating a common

understanding of such doctrine and procedures among Australian NGOs.[28]

15.27

ACFID, the peak organisation for Australian humanitarian NGOs, stated

that its engagement with the ADF is limited compared to that with other federal

departments:

Looking out to the next decade the one area that strikes us as

being a bit weak, given how effective the dialogue is with AusAID and how it is

emerging with the AFP as well, is having an informal dialogue with the ADF in

the way we do on a variety of other issues with other agencies.[29]

15.28

According to ACFID, there were advantages to be gained through better

dialogue between the military and civilian sectors and from NGOs having a

better understanding of the way the ADF plans and prepares for operations. In

particular, Mr Paul O'Callaghan, ACFID, saw benefits in further discussion

on 'issues to do with protection, humanitarian space and capacity building',

and in preparing for the transitions from short-term, security-focussed phases

of operations to longer-term reconstruction tasks.[30]

15.29

AusAID also commented on the importance of collaborative strategic

planning. In its view, 'Defence planners and task force commanders and their staff

need to be aware of the overall peacemaking and peacebuilding agenda and how

best to interact with them'. It proposed that by working closely with Defence

at the headquarters level, they could develop 'an effective plan for engaging

with the broad humanitarian and development community to achieve the Australian

Government's objective in undertaking peace operations'.[31]

Committee view

15.30

The committee believes that the aim of CIMIC should be to manage the

interaction between the military and civilian participants in a peacekeeping

operation so that their activities coordinate. But today's military operations

take place in complex environments where the military engage in a range of

activities not all of which are strictly military in nature. Clearly,

consultation and planning between the ADF and NGOs, from the earliest stages of

a peacekeeping operation, establishes the foundation for a good working

relationship in the field. The committee notes the call by NGOs for better

dialogue at a more strategic level between the ADF and NGOs.

CIMIC at operational level

15.31

At an operational level, the importance for military–NGO cooperation and

coordination is apparent. There are a range of coordination tasks confronting

both the military and NGOs. AusAID noted that coordination is required in the

areas of 'security, medical evacuation, logistics, transport, communications

and information management'. It agreed with the statement made in the UN

Civil–Military Coordination Officer Field Handbook, quoted earlier, that

coordination challenges also arise 'in providing humanitarian actors with

access to affected populations, while ensuring they do not become a target...minimising

the competition for scarce resources such as ports, supply routes, airfields

and other logistics infrastructure'.[32]

15.32

The committee first considers the extent to which the ADF has developed

a CIMIC capability.

Developing CIMIC capability

15.33

Some NGOs expressed concerns about ADF's CIMIC capability. For example, referring

to INTERFET, the Australian Institute of International Affairs was of the view

that CIMIC relationships were generally ad hoc and there was a lack of

CIMIC experience.[33]

It stated that a general lack of resources available for civilian tasks led to

the conclusion that the ADF 'lacked specialist civil–military capability, and

that in any future coalition operations such capability was a major

requirement'.[34]

15.34

Austcare suggested that the ADF had been slow to develop and implement

this capability.[35]

It pointed to more recent events in Timor-Leste in 2006 where, in its view,

'civil-military assets were not applied with optimal effect, causing dissatisfaction

with the local community as well as among humanitarian agencies and NGOs'.[36]

15.35

World Vision Australia reported inadequacies also based on the recent

experiences in Timor-Leste. It noted incidents where certain parts of the ADF

were engaged with civil society but 'when asked if and how they related to

CIMIC, they did not seem to know of its function regarding their operations'.[37]

15.36

The importance of developing an effective CIMIC capability takes on a

greater significance in peacekeeping operations where Australia is taking a

lead role. AusAID submitted that there is currently a gap in this area:

Necessity has prompted the OCHA [UN Office for the Coordination

of Humanitarian Affairs] to develop an effective humanitarian-focused

civil-military coordination capability for use in situations involving both

significant military and humanitarian operations. Australia needs to develop a

similar capability to be used in those few situations where Australia leads a

peace operation and there is no OCHA presence.[38]

15.37

The committee notes that the current government, in its pre-election policy

document on Defence, recognised that the recent deployment of ADF to Solomon

Islands and Timor-Leste demonstrated the need to improve ADF's CIMIC

capability. It indicated that it would expand the ADF’s CIMIC capability consistent

with the UN’s emphasis on civil–military cooperation.[39]

In conjunction with the committee's proposal that the ADF review its CIMIC

doctrine, the committee is of the view that the ADF should also examine ways to

strengthen its CIMIC capability.

15.38

The UN CMCoord policy has set down guidelines for the training of

civil–military coordination staff. The committee is of the view that the ADF

should consider these guidelines in reviewing their CIMIC capability.

Recommendation 17

15.39

The committee recommends that in conjunction with

its review of CIMIC doctrine, ADF consider ways to strengthen its CIMIC

capability.

15.40

Developing CIMIC capability, however, must take account of a number of

difficulties.

Challenges for CIMIC

15.41

A major challenge for CIMIC stems from the different expectations and

priorities of NGOs and the ADF. Mr March, AusAID, described the different roles

in the following way: the 'military seek to neutralise and separate actors;

civil response seeks to empower and reconcile actors'.[40]

Lt Gen Gillespie observed that the complexity of the security environment

complicates military–NGO relations in peacekeeping operations:

It is okay if you are in a very clinical humanitarian situation,

but if you add to it a security dimension...that is where we get the operating

space that creates those sorts of frictions.[41]

15.42

He referred to potential clashes in the early stages of a peacekeeping

operation between the humanitarian assistance and security phases:

If it is a particularly bad incident that you are dealing with,

then you will have traumatised people with no food and no means of income. That

is when NGO communities and defence need to have a far better understanding of

each other’s requirements and do it and coordinate their efforts in a better

way.[42]

15.43

Major General Ford acknowledged that issues surrounding the concept of

'humanitarian space' are particularly challenging. He agreed with the view that

the more robustly the military are required to act to maintain security, the

more difficult it is to achieve coordination and cooperation between the activities

of humanitarian organisations and the military. He added, 'There is a lot of

work going on now about determining how best you approach that'.[43]

AusAID also noted that the different priorities can create tensions:

Military deployments are undertaken to conduct specific

missions...and civilian actors operating in the same geographic area may be

engaged in a range of activities in support of possibly different mandates.[44]

15.44

The fundamental differences in the roles and functions of the military

and civilian peacekeepers are not going to change. Defence's primary goal will

be to create a secure environment while NGOs' objective will be to deliver

assistance to affected populations. Developing an effective CIMIC means

accepting, understanding and working with these differences.

Mutual misunderstanding

15.45

Evidence presented to the committee suggested that, to work

cooperatively and to coordinate their activities, organisations need to have a

better understanding of each other's roles and mandates. For example, Mr Shepherd,

WVA, explained that 'We cannot operate in that space without understanding the

context of the other players within that space'.[45]

15.46

Despite this acknowledgement, Major General Smith commented that there

'is a huge misunderstanding among many NGOs about the nature of the ADF'.[46]

In this regard, Lt Gen Gillespie acknowledged that Defence could improve:

I do think sometimes that we do not explain ourselves well

enough. As an organisation, we are perhaps not as well understood by NGOs as we

should be. I think, and certainly from where I sit directing it, we reach out

regularly to try and do a better job.[47]

15.47

The different views about the appropriate role of the military in

conducting humanitarian tasks pose another challenge for the civil–military

relationship, especially where the military's humanitarian activities may

create political complications for NGOs.[48]

NGOs—independence and impartiality

15.48

Humanitarian agencies generally work on the basis of common humanitarian

principles: neutrality, impartiality and independence. Some NGOs expressed

concern about the military delivering humanitarian assistance and the effect

that may have on the perception of NGOs' neutrality. Representatives from Oxfam

Australia explained that NGOs could be put in a dangerous position if any

perception arose that they were aligned to a political or military entity. As

an example, the Australian Institute of International Affairs noted that in East

Timor some NGOs were reluctant to use the designated civil–military operations

centre because of its proximity to the INTERFET headquarters.[49]

15.49

Oxfam argued that ADF involvement in humanitarian assistance can create

an impression that NGOs are in some way linked to military operations.[50]

It drew attention to the UN's Inter-Agency Standing Committee on Humanitarian

Affairs' guidelines that state, 'it is important to maintain a clear separation

between the roles of the military and humanitarian actors, by distinguishing

their respective spheres of competence and responsibility'.[51]

In this regard, Oxfam argued that the military are not humanitarian workers

and should not conduct humanitarian activities themselves, or be perceived to

do so.[52]

It further asserted that the ADF should avoid 'humanitarian rhetoric' or

language in describing its operational capabilities because of the likely

consequences for humanitarian agencies.[53]

Oxfam argued that the role of the military in peacekeeping operations is

intrinsically political:

We do not have any problem with the Australian military

distributing food or carrying out humanitarian operations in natural disasters

for instance. They are not complex emergencies; they are not politically

derived conflicts...It only becomes an issue where there is a conflict and there

are political agendas.[54]

15.50

Defence had a different perspective:

...there are some NGO groups who, through upbringing and all the

rest of it, look upon the military with great suspicion: we are ‘warmongers’.

We actually see ourselves as humanitarians.[55]

15.51

Dr Breen observed the humanitarian interest among ADF personnel and

commented that Australian peacekeepers have been disappointed when they have

not been able to be part of a team 'fixing up the circumstances of local people

who have had a tough time'. He said Australian peacekeepers 'wanted to respond

in a human way rather than just having their guns cocked ready to shoot'.[56]

15.52

Despite different views on the appropriate role of the ADF in a

'humanitarian space', it is clear that the ADF has resources that are useful in

a humanitarian effort. Within Australia, the ADF is a unique organisation in

terms of its ability to access conflict areas with sufficient equipment and

personnel to provide an immediate humanitarian response. AusAID noted:

...the primary military role in peace operations is to establish

and maintain a secure environment in which development can take place. On those

occasions when the environment is too hostile for civilians to conduct

development activities it may be appropriate for military forces to undertake

focused reconstruction tasks in line with the national development strategy...[57]

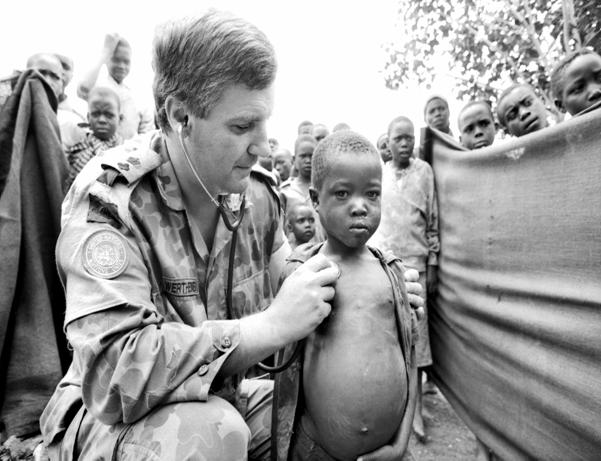

ADF providing

humanitarian assistance

Australian

Medical Support Force in Rwanda (courtesy Australian War Memorial, negative number MSU/94/0048/28).

An

engineer from the 3 Combat Engineer Regiment, as part of Timor-Leste Battle

Group 3, helps build a playground for the children of the Hope Orphanage in

Gleno (image courtesy Department of Defence)

15.53

Rear Admiral Ken Doolan, from the RSL, suggested that the ADF is a

legitimate resource for the government to use:

...if there were a humanitarian need, it would be churlish of the

nation not to use its Defence Force to assist to the extent that it could and

would wish to do so. Terminology really is not the important thing if you are

looking at the needs of the person on the ground.[58]

15.54

While some witnesses considered there were distinct roles for

humanitarian and military agencies in peacekeeping operations, others provided

a more nuanced perspective. The Australian Red Cross was of the view that there

is a need for recognition and respect for each other's different roles and

principles. Mr David Brown, Asia Manager, Australian Red Cross, said:

I think we would be disingenuous if we said that the military

does not, in many circumstances, have a role to play as humanitarian agents.

Conversely, there have been many examples of the military saving lives through

its humanitarian intervention. Where the military has not been deployed, in

some cases, it has also cost lives. So we do not want to say that we are

talking about the humanitarian workers over here and the military over there...

But we do have some very strong principles about neutrality and about

impartiality.[59]

15.55

There are immense practical considerations in facilitating a

humanitarian response to conflict. Dr Breen noted that in hostile environments,

where the need is immediate and delivering aid and sustenance to people is

difficult, the military is inevitably the conduit.[60]

He was of the view that it is not an aim of the military to subsume the role of

NGOs. In his experience, the ADF always steps aside to allow NGOs to do the job

'if they are up to it and they are prepared to deploy their people under the

same austere conditions under which the military work'.[61]

15.56

Defence did not resile from the political basis of its operations. Both

Defence and RSL witnesses noted that the ADF does not undertake humanitarian

work voluntarily; its activities are a matter of government policy.[62]

Even so, the committee notes the guidance offered in CMCoord which states that:

All non-security related tasks must be coordinated fully within

the mission, with the UN Country Team and with the larger

humanitarian/development community, depending on the context.[63]

15.57

Again, the emphasis is on achieving an integrated mission where the

humanitarian activities of the military and civilian components are

complementary.

15.58

Mr Shepherd, WVA, observed that the extent to which the military should

engage in humanitarian work is of long-standing debate, upon which there is

little agreement even within NGO circles. He acknowledged that tension is

created between the military and humanitarian workers: 'it will always remain

for us—how do we actually operate within that same space when we have quite

different mandates'.[64]

Committee view

15.59

Clearly the complex foreign policy space in which peacekeeping

operations occur brings different pressures on the relationship between

humanitarian and security agencies. The committee recognises the critical role

of the ADF in creating a secure environment and the important work of

humanitarian agencies in providing assistance in contemporary peacekeeping

operations. Together the military and civilian agencies create the conditions

necessary for rebuilding a state.

15.60

In some instances, due to the level of security risk or the lack of

existing infrastructure, the military may be the only, or the most able,

organisation to provide humanitarian relief. The committee considers it

appropriate that the government use available resources, including the

military's material and logistical resources and the skills of its members

where required, to meet such need.

15.61

Nonetheless, it is clear that when engaged in humanitarian work, the ADF

needs to appreciate and respect the concerns of NGOs, especially the importance

they attach to neutrality and impartiality. On the other hand, NGOs need to

understand the reasons the military becomes involved in delivering humanitarian

aid. Mutual understanding and close liaison based on regular consultation,

joint planning and training would help the ADF and NGOs to resolve tensions. On

a practical level, these would also encourage a more economical, efficient and better-targeted

use of resources.

Information sharing

15.62

The different agencies that are involved in a peacekeeping operation

obtain their information about local conditions from various sources. For

example, NGOs can be well known in local communities and have a good

understanding of the local environment, social context and issues underpinning

conflict. Defence has formal intelligence-gathering infrastructure and

relationships as well as the networks it builds in local communities.

15.63

The information and insights that different organisations gather can be mutually

useful for all in achieving their aims, but information exchange is not

necessarily straightforward or appropriate. There are a number of constraints

in disseminating information.

15.64

A common theme in evidence from NGOs concerned the sensitivities

associated with information sharing. They explained that an organisation that

shares security-related information risks perceptions of partiality. Such

perceptions can be both inhibiting and dangerous for humanitarian agencies that

rely on their neutrality and independence.

15.65

Although recognising limitations, the Australian Red Cross submitted

that information exchange between humanitarian agencies and security forces can

be appropriate:

...to ensure their neutrality (and their protection) one must distinguish

between information about the humanitarian situation on the ground, and

information about military/security issues in their area of operation. To provide

the former can assist in the provision of humanitarian assistance and decrease

tension, whereas to provide or be perceived as providing military/security

information may increase tensions and hamper access and security for humanitarian

agencies.[65]

15.66

It noted that such a distinction between types of information is not

always categorical and its personnel need to err on the side of neutrality and

impartiality. They should only share information that is 'useful to the

humanitarian situation—that is, the victims on the ground'.[66]

15.67

For security and mission-specific reasons, Defence is also constrained

in the information it shares. Nonetheless, there remains much scope for the ADF

and NGOs to keep each other informed about matters relevant to the operation.

AusAID took the view that there will always be tensions with regard to

information sharing. It stated:

It is appropriate for NGOs to provide details on their

capabilities, infrastructure if any, plans, concerns, etc, and for the military

to provide information, as appropriate and consistent with their own force

protection, on their military goals and policies (including rules of

engagement), as well as information on military hazards to NGOs (e.g. known

minefields, unexploded ordinance), and information on civilian access to

military support (e.g. medical facilities).[67]

15.68

Thus, for practical and safety reasons, there is a need for information

exchange. Oxfam, however, expressed concern about being able to obtain

necessary information from the military:

...timely information and clarity on mandates, rules of

engagement, division of roles and responsibilities and mission parameters have

in various cases been difficult to obtain. This information is necessary for

humanitarian organisations to assess programme viability and security

protocols.[68]

15.69

It was of the view that RAMSI had exposed the problems of lack of timely

and accurate information on the mission's mandate and operations.[69]

15.70

The committee accepts that the exchange of information between the military

and other organisations at an operational level will inevitably be constrained

by factors such as mission requirements and each organisation's principles and

needs. However, there are clear benefits to, and in some cases compelling

reasons for, having well-established and effective communication networks

between the military and civilian sectors.

15.71

Having said that, the committee is of the view that NGOs need to

appreciate the critical work of military peacekeepers, who at times place

themselves in harm's way to secure a safe environment that then enables NGOs to

carry out their work. The committee understands the importance of neutrality

and impartiality to NGOs, but it also believes that they have a responsibility

that extends beyond looking after their own safety and those under their care

to include those who are protecting them. This responsibility should be a major

consideration when deciding whether or not to disclose information to the

military.

Command structures

15.72

AusAID noted that 'NGOs are structured relatively informally and value

diversity of commitment and input, while a military has the onerous

responsibility of the management of and (as required) application of lethal

force'.[70]

Thus, unlike the military, the NGO community does not have a unified,

hierarchical command chain for passing on information. It is not a homogenous

body with common ideologies or perspectives. Dr Brett Parris, Senior Economic

Advisor, WVA, observed:

NGOs are constituted differently...There are also a range of views

among the NGO community on engagement with the military and police and that

just complicates some aspects in getting a single coherent NGO view on those

sorts of sensitive issues.[71]

15.73

It was of the view that the flatter and fluid structure of humanitarian

organisations reflects their aim of including local people and communities in

the decisions that affect them. This structure means that decision making can

take longer.[72]

15.74

From Defence's perspective, the differences between NGOs, including in

their attitudes to the military, can make coordination challenging.[73]

Lt Gen Gillespie observed that tensions on the ground usually relate to the

decision-making process within the NGO community. He noted that the ADF has a

unified command structure, giving it a clear path through to the appropriate

military commander to resolve issues during operations suggesting:

If the NGO organisations were to have a similar coordinating

mechanism then in my humble opinion a lot of that friction would go away.[74]

15.75

Lt Gen Gillespie informed the committee that he 'would be delighted to

see an NGO coordinating body that we could work with in the places that we go

to'.[75]

15.76

WVA acknowledged that the ADF's hierarchical structure, with clear

command and control lines, enables it to make decisions quickly. At the same

time, the military organisation can be difficult to relate to if there are no

clear access points. WVA noted the usefulness of having, within the military,

appropriate points of contact that understand both cultures and are 'better

able to facilitate dialogue'.[76]

ACFID, the peak body for Australian NGOs, related a relevant experience from East

Timor:

...We were advised directly by the CEOs of several agencies that

there was a real possibility of significant bloodshed. We were asked if we

could pass on this information. Regrettably, because we have not really been

able to establish a useful lower level connection to operations command to pass

information on, we ended up going through more political channels and passing

it up to the Parliamentary Secretary for Defence. That was probably not the

best way to do it, frankly...there could well be value in simply having a point

of connection where, if we do have what seems to be credible information from

serious people...we can contribute that...But, at the moment, we do not have that

capacity.[77]

15.77

Evidence to the committee suggested that NGO consultation with the ADF

is occurring on an ad hoc basis. The dialogue between the military and

NGOs in general stands to improve if both sectors could provide a central point

of contact through which this engagement can occur. The ADF should appreciate

that those outside the organisation do not have a clear understanding of how

they can gain access to relevant ADF personnel and should review its mechanisms

for information exchange. This observation also relates back to ADF CIMIC

capability and the need for it to have adequate numbers of appropriately

trained staff deployed with their peacekeeping contingents.

15.78

Despite difficulties in establishing clear communication networks, the

ADF and NGOs do converse during an operation. Both Defence and some NGOs

observed that coordination occurs at a practical level on the ground. Lt Gen

Gillespie was positive about the ability of the ADF and NGOs to resolve issues

in operational areas, stating 'I cannot think of any occasion in the last

decade where we have undertaken major security operations in a humanitarian

environment where we have arrived at an intractable problem between the NGO

community and ourselves'.[78]

Oxfam representatives commented that NGOs and the military are always

negotiating and coordinating: the military and humanitarian coordinators meet

weekly or more often 'so that we can negotiate this space so that they can

protect us and civilians at the same time'.[79]

Summary of impediments

15.79

The committee has identified a number of impediments to effective

coordination and cooperation between the military and civilian sector. They

include:

- ADF's current limited CIMIC capability;

- the diverse and heterogeneous nature of NGOs;

- the different roles, functions and priorities of the two sectors,

especially during times of heightened conflict and violence, where they are

occupying the same space;

- misunderstandings about each other's roles and priorities;

- contested humanitarian space where the military may deliver

humanitarian services, and its influence on perceptions of NGO impartiality and

neutrality;

- sensitivities about sharing information; and

- command structures that create communication difficulties between

the military and NGOs.

15.80

Dr Breen was of the view that the approach of the security sector to

coordinating with other agencies is 'changing in a positive way', and observed

a 'very different mindset from some years ago'.[80]

Consistent with this view, Lt Gen Gillespie commented that a 'huge amount of

work' has been done in the last three years by military and NGOs to improve

cooperation.[81]

15.81

OCHA believes that training is a primary means for sharing lessons

learned about civil–military relations and building informal networks. The committee

now looks at the current measures taken by the ADF and NGOs to meet the

challenges to coordination and cooperation.

Pre-deployment training

15.82

The ADF engages NGOs to deliver particular components of its

pre-deployment training, mainly relating to cultural awareness or human rights

and humanitarian law. For example, the Australian Red Cross noted that it both

participates in, and presents at, the ADF's International Peace Operations

Seminar (IPOS), CIMIC courses and the UN military observers course run by the ADF

Peacekeeping Centre (ADFPKC).[82]

The Australian Red Cross also runs an ADF instructors course for interested ADF

members involved in training in the laws of armed conflict.[83]

15.83

In 2006, AusAID appointed a Civilian–Military Liaison Officer within its

Humanitarian and Emergency Section to assess AusAID's involvement in ADF

training activities and to advise on further areas of engagement.[84]

AusAID also held a Humanitarian Forum in 2006 with a particular focus on

civil–military relations, including how the shape of the initial crisis

response and the choice of instruments and approaches affect future

state-building endeavours.[85]

15.84

The Asia Pacific Centre for Military Law (APCML), an initiative of the

ADF's Legal Branch and the University of Melbourne Law School, runs a week-long

CIMIC course. Its objective is to inform participants from both government and

non-government agencies on the planning factors that are crucial to the ADF's

conduct of CIMIC activities.[86]

The course comprises topics such as the law of peace operations, military

operations law and civil–military cooperation in military operations.[87]

Joint training exercises

15.85

Several government agencies and NGOs, including AusAID and WVA, attended

the Australian Command and Staff College Exercise Excalibur in 2006. Another

joint exercise, Exercise Talisman Sabre, was conducted in 2007.[88]

The exercises focused on joint operational planning for a complex stability

operation, involving military planners, representatives of other government

agencies and NGOs working together.[89]

WVA reported that Exercise Excalibur was 'a valuable experience, with numerous

lessons for our civil–military engagements'. It considered, however, that such

exercises could be made even more realistic if NGOs were engaged in the initial

planning process.[90]

WVA observed that taking these forums further into the future would depend on

dialogue with the ADF and other players.[91]

Suggestions for strengthening CIMIC

15.86

A number of witnesses made suggestions for improving liaison between the

ADF and NGOs, including at the pre-deployment planning level. For example, Mr O'Callaghan

saw great benefit in the NGO sector being able to engage with the ADF in a

structured but informal setting such as a bi-annual roundtable. He preferred an

informal approach because 'it is more likely to be a productive exchange of

views if it is done in a way which enables the ideas to be tested out'.[92]

This proposal had been put to Defence but Mr O'Callaghan indicated that Defence

considered it appropriate for AusAID to handle all policy dialogue with NGOs.[93]

15.87

Austcare recommended that the Australian Government establish an

independent national institute as a 'centre of excellence' to undertake

necessary training and research on peacekeeping. According to Austcare, the

centre would give 'particular focus to strengthening civil–military relations'.[94]

The committee notes a similar proposal by the Centre for International

Governance & Justice (CIGJ) for a centre of excellence for civilian

peacekeeping in Australia. CIGJ saw this centre as an opportunity for

Australian government agencies to provide more strategic support to NGOs by

offering 'specialised civilian peacekeeping training'.[95]

Clearly such a centre would be an ideal vehicle for promoting the development

and strengthening of CIMIC.

15.88

Major General Smith referred to a proposal Austcare had put to ADF for

NGOs, ADF, AFP and AusAID to review jointly four case studies where the ADF and

NGOs have been in the same place at the same time: Afghanistan (a high threat

environment); Solomon Islands and East Timor (two not-so-high threat but

conflict related environments); and Aceh after the tsunami (a non-conflict

emergency). Major General Smith said no response had yet been given.[96]

15.89

According to WVA, NGOs should also be actively seeking ways to improve

engagement with the ADF. It acknowledged that development and understanding of

CIMIC doctrine was not a one-way process, with the onus also on humanitarian

agencies to improve their understanding of CIMIC. In that regard, WVA had

employed a person to focus on civil–military relationships, including engaging

with peacekeepers, the AFP and international partners. It considered that

'there is no way that World Vision can have an understanding of civil–military

relations without that direct kind of engagement'.[97]

15.90

Based on the evidence, the committee sees potential to improve CIMIC.

For example, it mentioned in Chapter 13 the informal Peace Operations Working

Group, chaired by DFAT, with members from Defence, AFP, AusAID and A-G's. The

group's focus is not on specific operational issues, but more thematic issues

around Australia's involvement in peacekeeping operations. This existing forum

could be gainfully used to improve dialogue across the government and NGO

sectors, including between the ADF and NGOs.

15.91

The committee also recognises that joint training and education can help

establish common understandings and trust and provide opportunities for the

military and civilian sector to work through coordination problems. In this

way, CIMIC becomes not only a force multiplier but also an 'aid multiplier' by

improving the delivery of aid.[98]

15.92

These proposals are worthy of serious consideration and illustrate the

need and the potential for the Australian Government, ADF, AusAID and NGOs to

strengthen CIMIC.

Committee view

15.93

During the inquiry, some witnesses referred to what they believed were

deficiencies in the ADF's CIMIC capability. A number of NGOs also called for

improved dialogue with the military, better understanding between the

organisations and closer involvement in the planning of peacekeeping

operations. They have made suggestions that would require Defence to strengthen

its engagement with NGOs, including through roundtables and case studies.

Communications and command structures could be improved, which would facilitate

better coordination. The committee also notes that NGOs could facilitate this

process through better organisation and liaison amongst themselves. The committee

notes ACFID's role as the peak body for humanitarian NGOs and sees capacity for

ACFID to form a better conduit between Defence and the NGO community.

15.94

The committee has recommended that Defence review its CIMIC doctrine and

consider ways to strengthen its CIMIC capability. It now builds on these

proposals.

Recommendation 18

15.95

The committee recommends that AusAID, ACFID and Defence jointly review

the current pre-deployment education programs, exercises, courses and other

means used to prepare military and civilian personnel to work together in a

peacekeeping operation. The committee recommends further that based on their

findings, they collectively commit to a pre-deployment program that would

strengthen cooperation between them and assist in better planning and

coordinating their activities.

15.96

The committee sees merit in Austcare's proposal for four collaborative

case studies to identify ways to improve coordination between the security and

humanitarian elements of peacekeeping operations.

Recommendation 19

15.97

The committee recommends that Defence, AFP, AusAID and DFAT commission a

series of case studies of recent complex peacekeeping operations, as proposed

by Austcare, with the focus on the effectiveness of civil–military cooperation

and coordination. Their findings would be made public and discussed at the

Peace Operations Working Group mentioned in Recommendation 14.

15.98

To this stage of the report, the committee has mentioned a joint

training facility as a means of improving the effectiveness of Australian

peacekeepers and Australia's overall contribution to peacekeeping. Evidence in

this chapter adds weight to this case. Through training programs, seminars and workshops,

such a facility could draw together teachers, students, researchers and former,

current and future peacekeepers from government and non-government sectors. The

facility would enhance CIMIC and develop future forms of civil–military–police

coordination. It would also provide a site for empirical, evidence-based research

and the evaluation of past and current practice. It would operate at the policy

and operational levels, ensuring that Australia keeps abreast of new ideas and

approaches to peacekeeping. It would also be involved at the practical level by

assisting individual agencies prepare their personnel for deployment and foster

a whole-of-nation approach to peacekeeping. The proposal for a centre of

excellence is examined in greater detail in Chapter 25.

Conclusion

15.99

Today, the ADF shares peacekeeping space with many government and

non-government actors. For this reason, the committee feels that Australia

requires a more holistic approach to coordinating its peacekeeping efforts. It has

made a number of recommendations but they are by no means exhaustive. The

potential for improving CIMIC and, indeed, extending the CIMIC framework to

include all government agencies is great.

Part IV

Partnerships—host and participating countries

To this stage of the report, the committee has been

concerned with the effectiveness of Australian peacekeepers from the individual

agency, whole-of-government and whole-of-nation perspective.

The committee now considers Australia's role as a

participant with other countries in a peacekeeping operation. It first explores

some of the challenges Australian peacekeepers face in establishing and

maintaining a constructive partnership with the host country. It is

particularly concerned with peacekeeping operations where Australia is taking

an active or lead role and bears a heavy responsibility for achieving a

well-coordinated, cohesive mission. According to United Nations Peacekeeping

Operations: Principles and Guidelines, an integrated mission is one where

there is:

A shared vision among all United Nations actors as to the

strategic objectives of the United Nations presence at the country-level. This

strategy should reflect a shared understanding of the operating environment and

agreement on how to maximise the effectiveness, efficiency, and impact of the

United Nations overall response.[99]

In subsequent chapters, the committee examines Australia's

relationship with its peacekeeping partners and the difficulties encountered in

achieving an 'integrated operation'.

The committee identifies the main factors that contribute to

effective coordination and cooperation between the partners in a peacekeeping

coalition and whether Australia could do more to enhance this relationship. In

this context, it considers the implications for the way Australia prepares its

peacekeepers for deployment. The committee also looks at how effectively Australia

engages with the peacekeeping aspects of the UN as the international body

charged with maintaining international peace and security and with regional

associations.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page