Chapter 6 - The teaching profession

The underlying problem is that the social status of teaching has

dropped dramatically. Every occupation that has been invented since 1970 is a

graduate occupation and has gone into the occupational hierarchy above teaching.

When I was a boy most accountants did not have degrees. Now the biggest faculty

in every university is a commerce faculty, and they are all people who are

expecting to earn more and have higher social status than teaching. The

burgeoning of the university industry in Australia is actually about the

creation of degreed occupations of a higher status than teaching.[1]

6.1

When this committee inquired into the status of the teaching profession

in 1996-97, it observed that teaching was a highly complex and demanding

activity, buffeted by shrinking budgets, alarmist media reports, unsupportive

ministers, a crowded curriculum, and the disappearance of support services. It

went on to describe how, despite what it saw as evidence of strong commitment

and innovative teaching practices, there was a morale crisis related to the

belief that the status of the profession was disturbingly low. Few teachers

recommended that their brighter students enter teaching, and the academic entry

level to university teacher training courses was notoriously low.[2]

6.2

What has changed over the past ten years? On the whole, not a great

deal, except that the political and economic context has changed. The committee

perceives that there is now an appreciation of the need for a more enlightened and

collaborative approach to schools' policy. There is more funding available than

10 years ago. The debilitating years of bureaucratic restructuring and

frustrating curriculum experiments are now a receding memory in most

jurisdictions. Even perceptions of professional status are beginning to change,

due in part to innovations like state teacher registration boards. But

fundamental problems identified in the 1998 report remain, especially in regard

to entry into the profession and teacher retention rates. This inquiry has

uncovered concerns not directly referred to in the earlier report: the academic

content of teaching degrees, particularly discipline-based knowledge; and the

quality of teaching. The committee hopes that there may be more willingness in

this first decade of the 21st century to take a more honest look at

cherished mindsets and institutional deficiencies with a resolve to fix as much

as we can.

6.3

In the meantime, across the country, a high proportion of teachers

remain under considerable strain. This inquiry does not have as its central

focus the pressures on teachers, but in noting evidence touching on teaching

quality, and the demands of the curriculum, some consideration of issues

affecting the profession can scarcely be avoided.

The school milieu

6.4

First, it is important to consider the task and operational field of the

profession. One does not enter teaching without a sense of the importance of

imparting knowledge or skills, or of bringing about some improvement or

development in the minds and outlooks of students. As Dr Geoff Masters and his

colleagues at the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) have

reminded the committee, no concept is more central to the work of teachers than

the concept of growth, and that teachers have a fundamental belief that all

learners are capable of progressing beyond their current level of achievement.[3]

As another ACER researcher told the committee in relation to why people enter

the profession:

The research shows that key drivers are the pleasure and stimulation

that they get from working with children and colleagues and seeing kids develop

and learn.[4]

6.5

That is what good teaching is about, but as the committee heard,

teachers find many impediments laid in their path. They are confronted by

resistance to learning. They are often confounded by students with such a lack

of any sense of appropriate behaviour, social skills and worldly experience,

across entire classes that it is hard for inexperienced teachers to establish a

learning connection or point from which to progress. This is why teachers tend

to gravitate to middle-class schools in middle-class suburbs.

6.6

The committee also believes that a proportion of teachers, who have

spent 20 years or more in the classroom, are in danger of losing their drive

and their enthusiasm in learning new skills and knowledge. This may partly

arise from a lack of challenging professional development. It is not a

phenomenon confined to teaching, but its effects have more consequences there

than in most other jobs because of the need to be seen to perform. In

combination with low morale, which also affects teachers' performance, this

would account for what is probably an unacceptably high level of

under-performance. The committee has no evidence on the incidence of this

problem. It is an area of school and system administration which appears to be

under-researched. The committee is not concerned here with demonstrably

incapable performance, which is usually so obvious that it has to be 'managed'.

It is concerned with lacklustre teaching which relies on habit, old method and

old knowledge, and which can be safely ignored or tolerated by school

management as well as by bored and underachieving students. One correspondent

to the Ramsey inquiry into teacher quality in New South Wales (see below)

wrote:

...a teacher might well get fired for predatory sexual behaviour

with a young student, but others who mess up the lives and achievements

prospects of their students through low professional competence remain

entrenched in the system.[5]

6.7

Such teachers may be rehabilitated, but identification, diagnosis and

treatment is a challenge which appears not to be a priority. This challenge may

be taken up by the newly established teacher registration bodies, but the

committee fears that employing authorities will have the capacity to frustrate

quality teaching measures which are administratively inconvenient.

6.8

In his review of teacher education in New South Wales, Dr Gregor Ramsey

described the incidence of stagnation in schools which occurred when teachers'

long periods of 'professional passivity' weakened their morale and self-image.

This culture rewarded patience, not learning, and was an anomaly in a society

which normally rewards performance and creativity. Dr Ramsey also noted that

there are degrees of proficiency amongst teachers, and until some standards

have been agreed, and measures put in place to enforce them, the standing of

teaching in the community will not improve.

6.9

Notwithstanding this teaching milieu, in schools geared toward student

growth and achievement, it is easy to understand why Australian students do

well in relation to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and

Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). In other schools,

the reasons for a long tail of under achievement are also easy to identify.

Education writer and former academic Alan Barcan has some depressing comments

to make on a sub-culture of under-achievement:

With values trending from stable and predictable to situational,

it is no longer possible to assume that students will value qualities like

application, ambition and achievement...The well-documented emergence amongst

adolescents of a deep caution, even cynicism, about institutions, authority,

government and education are, almost certainly, incrementally taking their toll

on student performance. Though certainly not universal in their impacts, the

valuing of work and the setting of personal goals is giving way to short-term

self-focused living for many adolescents and, with it, the motivation for

learning and the commitment to pursuing academic targets have both come under

considerable pressure...The inability of many families to provide basic knowledge

and values, the primitive culture of many peer groups, the deteriorating

culture pervading the media, mean that many students are no longer capable of

absorbing even a simplified version of the traditional culture.[6]

6.10

In Chapter 1 the committee recognised the issue of inequity as one which

dogged efforts to improve education standards across all schools. There is not

much that schools can do to influence the lives of students away from school. It

is the burden that students bring to school which so often disadvantages their

performance. Education authorities and schools go to considerable lengths to

perform an overall duty of care for students, but the committee believes that

teachers are already up against the limits of their capacity to substitute for

parents in areas of life skills, personal values, and behaviour. Some

submissions were critical of the failure to understand what schools are

confronted with today. As the Australian Education Union pointed out:

The students who come to school today live in a very different

world from that which adults inhabited when they were at school. Their

experiences, their environment, their expectations and the expectations placed

upon them have changed radically from the past. They are in many ways more

sophisticated, but at the same time much of what happens in their lives outside

school makes it that much more difficult for them to succeed.[7]

6.11

The committee did not receive explicit submissions on the learning

culture of schools, but there was considerable weight

put on the problems of inequity, and the failure of schools to deal with

under-achieving students, especially those in the compulsory years of schooling

who were marking time because, for one reason or another, they had reached the

end of their growth in formal schooling. The implication for teachers is

whether, if they were more skilled or experienced, and perhaps better resourced,

they might have made a difference. The committee suggests that the experience

of too much failure is a disillusioning experience for a high proportion of

relatively inexperienced teachers, and this leads to high attrition rates.

Attraction and retention

6.12

Across the country the committee heard a common refrain of schools and

systems needing more teachers and retaining them longer. Insufficient numbers

are being attracted.[8]

The effects of these shortages will become more serious problem for schools as

the more senior and experienced teachers resign or retire. The shortage extends

across the curriculum. While the shortage particularly affects rural, remote or

'difficult' schools, it is not confined to any one sector or state. There is a

severe shortage of some specialist teachers, especially in mathematics and the

sciences. As related earlier, the proportion of secondary school mathematics

teachers with majors in mathematics in their degrees is declining steadily. Such

is the shortage that teachers are often asked to teach subjects in which they

have no expertise. The Independent Education Union of Australia described it as

unacceptable that most teachers can report that during their career they have

been required to teach some part of the curriculum for which they are not

well-qualified, and then have to bear criticisms of the quality of their

teaching.[9]

6.13

Teaching quality is compromised when a teacher does not have the

knowledge or understanding of a particular subject. Some teachers may acquire it

over time, usually through formal study, and, or intrinsic interest. This is

unlikely to be commonplace. A teacher without the necessary literacies would

not be able to teach the subject with confidence or accuracy. It is also possible

that the subject is taught without depth, or alternately, greater emphasis is

given to those parts of the curriculum in which the teacher does have

expertise.[10]

In relation to this, the committee notes evidence given to the House of

Representatives committee looking at teacher education in 2005 by Dr Lawrence

Ingvarson from ACER who said:

The research indicates that you cannot use what are known to be

effective teaching techniques unless you do understand the content deeply. If

you do not understand, you are forced back on to the worst didactic textbook,

going-by-the-rule book sort of teaching. A deep understanding frees you up to

use good pedagogy, to discuss ideas, to relax, to open up the discussion, to

throw away the textbook and to throw away the work sheets because you are

interested, you understand the ideas and you know how to promote those ideas

and that discussion.[11]

6.14

This is what the committee understands to be good teaching. It begins

with enthusiasm for the imparting of knowledge and ideas, and drawing an equal

measure of enthusiastic response from students. However, there might be some

evidence of a lack of enthusiasm from the outset.

6.15

The committee heard that many new entrants into the profession see

teaching as only a temporary job. It is a port of call on the way to what many

hope will be a more desirable career destination. Young graduates, in

particular those with strong academic degrees, find it hard to imagine spending

thirty years in the classroom doing much the same thing as when they started.

The committee believes that this will always be a characteristic of the

teaching profession. Many enter the profession but only those with a strong

sense of vocation stay on.

6.16

But the committee also believes that much more should be done by schools

and systems to reduce this waste of talent. There is an important role for

principals in mentoring and encouraging obviously talented teachers. In theory,

independent schools should have an advantage in keeping teachers on because

long-term staffing policy is within their capacity to manage more effectively

than in systemic schools. Granting more staffing autonomy to public schools is an

important reform.

Quality of entrants to the profession

6.17

The committee was told that the problem of attraction and retention is

in addition to the lower intellectual quality of people entering the teaching

profession.

In 1983, the average person entering teacher education was at

the 74th percentile of the aptitude distribution...By 2003, the average

percentile rank of those entering teacher education had fallen to 61. ...Focusing

on women (who make up about three-quarters of new teachers), the probability of

a woman in the top 20 per cent of the academic aptitude distribution entering

teaching approximately halved from 1983 to 2003. Meanwhile, the probability of

a woman in the bottom 50 per cent...doubled.[12]

6.18

This information is consistent with evidence from Professor Bill Louden.

He pointed to entry scores for trainee teachers and concluded that many got

into university with very low TER scores. Universities admitting such students

ran very large teacher training programs.

When you start thinking of the size of these institutions and

multiply that by the standard, who are the big providers and what are their

standards like, you would have to say that there is a problem...People often talk

about the problems in physics and mathematics and I do too, but underlying that

the larger problem is that the genetic subsidy of women to teaching has been

withdrawn. Women used to think they could not be lawyers. They are often not

happy being lawyers either, but they used to think they could not be lawyers,

that they could do nursing or teaching. The old bursary schemes that paid for

working class people’s higher education have been withdrawn, so there is no

longer a kind of a working class intellectual subsidy into teaching. The women

that teaching attracts are nothing like, on average, the same intellectual

standard as those before.[13]

6.19

The percentile decline is not evident at every university and is

undoubtedly due to some universities having lowered their Tertiary Entrance

Ranking (TER) for education courses. Clearly, the universities have their

reasons for making such adjustments. One such reason would be the issue of

supply and demand. While universities continue to offer education courses, the

demand for places within those courses has changed. There are now a huge range

of options available to tertiary students, and those students with the highest

TERs are not usually interested in a teaching career.[14]

6.20

The percentile decline does not take into consideration those students

who enter university other than via the TER system, such as mature age

students. Nor is it wise to suggest that the TER is the sole indicator of

academic quality. The committee does, however, believe that there is a

correlation between a teacher's academic achievement and that of his or her

student. The apparent decline in the calibre of trainee teachers, as evidenced

by the TER requirements, is therefore a matter of concern.[15]

Overcoming teacher shortages

6.21

The committee acknowledges that there will be no quick and easy answer

to solving the current teacher shortages.[16]

This section of the report considers aspects of teaching conditions which could

be improved to make the profession more attractive. As a preliminary comment,

however, the committee states its belief that regardless of what improvements

to teaching conditions are made, it is unlikely that there will be significant

increases in the number of high-achieving school leavers wanting to take up

teaching. The attractions of other professions will always be more apparent

than the vocational satisfaction that teaching offers more altruistic spirits.

To compound this problem, there will be an increasing proportion of teachers who

will see their teaching careers as relatively brief, a pathway to some other

occupation. For at least two generations teaching has been a working class or

rural springboard to better paid jobs. That pathway to social mobility is now

obsolete because too many other occupations fit that purpose.

Teaching: a profession or not?

6.22

As noted at the head of this chapter, Professor Louden told the

committee that the underlying problem is that the social status of teaching has

dropped dramatically over the past 30 years, and that every occupation since

invented is a graduate occupation which has gone into the occupational

hierarchy above teaching. The result has been ambivalence over the professional

status of teaching. That is, whether teaching is a profession or not.

6.23

The questioning of school performance, and the failure to attract people

of the same calibre into teaching, has influenced current interest in teacher

certification and performance pay. The view is that teachers are responsible to

an extent in organising the salvation of the profession, even though in the

case of teacher registration agencies, state governments have led the way. The

professional status of teachers is influenced to a large extent by the fact

that they are all employees. They operate under the school and (for most of

them) systemic authority. Their autonomy at the chalkface is regulated by a

curriculum, a syllabus, and by whatever collegial or departmental agreements

guide them in their teaching. A school is a social learning organisation in

which teachers have a crucial role, and they also operate under a myriad of social

and community constraints. They are public servants in the widest meaning of

this term. They are professionals, in a more narrow sense however, in that they

must be certified as being qualified, have special expertise, responsibilities

and a duty of care, with duties extending beyond any formal hours of work, and

an obligation for continuing self-education.

6.24

The issue of morale is crucial in teaching because job satisfaction

depends almost entirely on the sense of fulfilling a vocation. It relies on

seeing evidence of intellectual and character growth in one's students. The

committee thinks it likely that most teachers give little thought as to whether

they are regarded as professionals or not, when morale and job satisfaction

levels are high. It is the stresses and strains on teachers, and criticisms of

their efforts, that have concentrated minds on this matter. The Association of

Principals of Catholic Secondary Schools in Australia submitted that:

If we want people to believe they are professionals, first of

all we must tell them they are, we must treat them as if they are and we must

provide them with conditions that enable them to be professional.[17]

6.25

But the committee believes that the professional status of teachers is much

more complicated. A brief description of a profession is one which arises when

any trade or occupation transforms itself through:

The development of formal qualifications based upon education

and examinations, the emergence of regulatory bodies with power to admit and

discipline members, and some degree of monopoly rights.[18]

6.26

There are many important characteristics of a profession which are not

present within the 'teaching profession', including, fundamentally, an

autonomous and powerful regulatory or professional body whose function it is to

define, promote, oversee, support, and regulate the affairs of its members. The

committee notes that the teaching profession is seeking to acquire some

characteristics of the more established professions, but the committee believes

that, for reasons that go beyond the capacity of any government or society to

order, teaching will continue to be buffeted as much as any other occupation.

Teacher registration bodies

6.27

The committee believes that registration and accreditation bodies will

have interesting challenges to face in their progress toward becoming the

gate-keepers to the profession. This has the potential to bring them into

conflict with employers. Currently, it appears that state registration bodies

are more often creatures of education departments. The committee noted that one

of the witnesses representing the Queensland College of Educators was

concurrently an official of the education department in that state. On the face

of it, this represents a conflict of interest.

6.28

Potentially, an independent college of educators could accredit teachers

only in subjects which they are qualified to teach on the basis of their

university qualifications or specialisations. This would be entirely consistent

with the role of any other professional accrediting agency concerned with

maintaining quality standards. However, it would be an attitude or action which

school systems and employing authorities would strenuously resist because it would

restrict the authority of a school or a principal to direct a teacher to take a

particular class. It is commonplace for teachers to be directed to take classes

in subjects for which they are not properly qualified, if only because of

schools' legal duty of care. The committee is of the opinion that it is

unlikely that state-based or national professional regulatory bodies for

teaching could ever be relied on to back quality standards of professional

teaching in the circumstance described above.

Remuneration

6.29

For many witnesses, the most essential element of professional treatment

was that of remuneration. Professor Igor Bray argued that immediately

increasing base pay would send a message to the community that teaching is

valued. The Independent Education Union of Australia maintained that if the

base pay is not right, then the profession does not have the standing and

capacity to recruit.[19]

6.30

The fact that the base pay is not right was highlighted by many other

witnesses. Professor Michael O'Neill from the University of Notre Dame provided

an interesting comparison to the committee,

We need to bring the three Rs back to teaching. But they are not

the three Rs you would think I am talking about; they are ‘remuneration,

remuneration, remuneration’. We have a very sad tale to tell in Australia. It

takes teachers in Western Australia nine years to hit a ceiling...First-year

teachers [in the Republic of Ireland] start on a salary of $55,000, while most

of our teachers start on $45,000. Over 25 years, [teachers in the Republic of Ireland]

rise to a salary of $100,000. That gives them status and a position in society.

But, first and foremost, it gives them something to hold onto; it retains them

in the profession. They can see that their career is not finished after nine

years...At my colleague’s university, students enter with a TER that is

equivalent to the TER for law students and medical students. They fight for

places in education faculties.[20]

6.31

According to ACER:

The typical salary scale for teachers in Australia does not

place high value on evidence of teacher quality. Consequently, it is a weak

instrument for improving student achievement. It does not provide incentives

for professional development nor reward evidence of attaining high standards of

performance. Thirteen of 30 OECD countries report that they adjust the base

salary of teachers on the basis of outstanding performance in teaching, or

successful completion of professional development activities...Australia is not

one of them.

While progression to the top of the salary ladder is rapid in Australia

– it takes only 9-10 years for most Australian teachers to reach the top of the

scale compared with 24 years on average in OECD countries

– there are no further career stages based on evidence of attaining higher levels

of teaching standards. The implicit message in most Australian salary scales is

that teachers are not expected to improve their performance after nine years.[21]

6.32

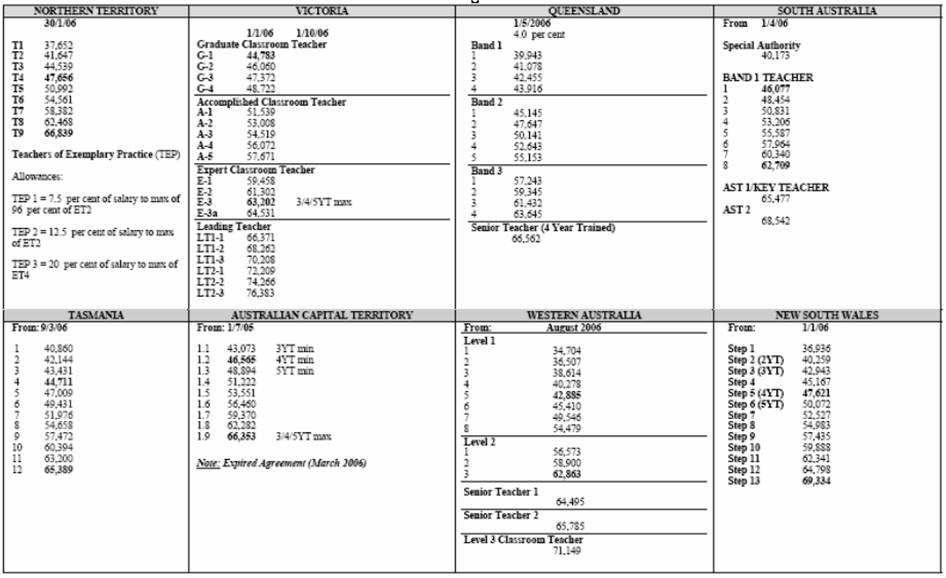

A table of current salaries adjacent shows the incremental stages for

government schools across the country.

6.33

The committee found general agreement between educators on how poorly

teachers are paid. Their relatively low pay affects the quality of entrants to

the profession, and this damages prospects for an improvement in education

standards at all levels. There are flow-on effects to business profitability

and efficiencies in public services. The committee is in favour of a

significant across the board pay increase. This should be implemented

regardless of whatever additional performance pay arrangement is finally

determined.

6.34

The committee is aware, however, that this would be a bold step for

governments to take. It would have the effect of elevating teachers' salaries

well over the rate paid to, for instance, health care workers generally. While

it would signal a long-term commitment to getting the basics of future national

growth right, it would also arouse some antagonism from those who would see

more benefit in alternative uses of the funding. While public schools teachers'

salaries are the province of state and territory governments, the

non-government school sector has traditionally been supported by the

Commonwealth, and additional funding avenues for teachers in this sector would

need to be explored.

6.35

Opponents of significantly higher pay would also argue—as would many

educationists—that higher salaries may not have the desired affect of

attracting a brighter cohort of trainees into the profession, because of the

peculiar nature and challenges of the job, and the fact that it makes special

vocational demands without the guarantee of corresponding vocational

satisfaction.

6.36

The committee believes that there are strong grounds for increasing the

base rate of pay for teachers across the current salary range. This should

incorporate some new scale which would spread the increments over a longer span

of a teacher's career. Arguably, the increments are now too closely grouped in

the first eight or ten years of service.

Performance pay

6.37

The issue of teaching quality, which occupied up to half of the committee's

time, quite naturally led to questions about performance pay. The issue has recently

aroused public discussion. Some witnesses were less than enthusiastic with the

idea of performance pay, as were submissions from teacher unions and other

associations. The committee recognises that the failure to elicit informed

comment was probably due to the fact that many educationists have not yet

focussed on the issue. The committee notes the ACER claim that a lack of understanding

about the complexity of developing valid and professionally credible methods

for gathering data about teaching and assessing teacher performance is the

reason why performance pay schemes have failed over the past 30 years.[22]

6.38

It is fair to report that performance pay is not opposed by many people

on grounds of principle so much as on grounds of

practicality. There is justifiable reservation about how a scheme could

fairly reward those whose efforts and achievements are not easily measurable.

This is particularly the case with teachers of students with disabilities and

learning difficulties, and where teams of teachers contribute to quality

learning outcome in ways which are difficult to disaggregate.

6.39

The purpose of performance pay is to encourage and reward excellence and

effort, provide incentive, and improve the quality of student achievement

overall. The committee recognises that there is a desire among all those

associated with school education to revitalise the teaching profession, and

this is the source of interest in performance pay. The committee is of the view

that teachers' salaries ought to be increased across the board and has

recommended that this be done. However, the view is also widespread, and shared

by the committee, that teachers of outstanding merit should be rewarded with

salary supplements, indicating to the community that the vocation of teaching

is valued.

6.40

Although the Government has a stated policy in support of performance pay,

it is at an early stage of development. This is evident from a reading of the

ACER research paper published in March 2007 which indicates the scope of ideas

for performance pay, and the need to engage in extensive investigation of

models which would be most appropriate for schools.[23]

In June 2007, the Minister for Education, Science and Training, the Hon Julie

Bishop MP announced a tender for an expert to develop models which could be

tested. The committee anticipates that this will be a formidable task and makes

the following references to important points arising from the ACER research

paper.

6.41

Dr Ingvarson and his team noted that any valid and reliable scheme for

assessing individual teacher performance requires multiple and independent

sources of evidence, and independent assessment of that evidence. No single

measure, such as exam results or a principal's assessment, would alone provide

a reliable basis for making a decision about performance pay eligibility.

6.42

There are currently three approved schemes for performance pay operating

in a number of states and territories, all of them having origins in the

Advanced Skills Teacher concept. This has been promoted by unions since the

early 1990s, but the concept is seen by disinterested observers to contain many

flaws. These flaws are evident in the various performance pay schemes.

6.43

There are three categories of performance pay schemes. The first is a

merit pay scheme, once used in many school districts in the United States. This

scheme is not standards or criterion based; evidence in support of the award is

often unreliable and of doubtful validity; and there is usually a fixed pool of

funds. In the second category are knowledge and skills-based schemes. These are

also common in the United States where bonuses are paid for the acquisition of

post-graduate qualifications. This has the merit of valuing teacher growth and

development, even though there is no evidence that having post-graduate

qualifications improves classroom performance. Finally, there is the certification

approach, which is an endorsement by a professional body that a member has

attained a specified level of knowledge and skill. An application would be

voluntary and made to one of the embryonic state certification agencies like

the NSW Institute of Teachers.[24]

6.44

At this stage of the debate, such considerations were academic to most

witnesses. The Australian Education Union told the committee:

We support a process that recognises that a teacher has met

professional standards that have been set and agreed by the profession and that

are externally assessed...It is a method that does not produce any negative

results within a school in terms of competition to the point of divisiveness or

being seen as an arbitrary decision by a school principal or anyone else...Having

said that, we are very concerned that the notion of performance pay—or

additional bonus, if you like—would become a substitute for real increases

across the board in teacher salaries.[25]

6.45

The committee would not want performance pay to be a substitute for real

increases in salaries. The Australian Education Union's conditional support for

performance pay drew attention to concerns which were foremost in the minds of

other witnesses. Dr Glenn Finger and his associates from Griffith University

highlighted issues of equity:

The opportunities for and challenges of being an effective

teacher are not uniformly distributed across schools and schooling situations.

To discriminate against teachers [who] work in schools and communities that

fail to afford support for their activities will only exacerbate the social

divide within Australia, erode the commitment and enthusiasm of teachers

working in challenging schooling situations and further demark many public

schools.[26]

6.46

Contextual factors, the complex nature of teaching and learning, and the

collaborative nature of people working together to produce learning outcomes

were concerns also echoed in the remarks of the Queensland Secondary

Principals' Association, which strongly opposed the entire concept of

performance pay, especially one based on student results. While this is almost

certainly a misconception, the committee noted that this is a common view:

In terms of taking...students from where they were to where they

were heading and achieving, the distance travelled was enormous but the results

were still poor. That to me is the basis of what is wrong

with performance pay. If you look for a simple measure of student

results, it just does not take into account context...The damage this would do to

the totality, to the wholeness, of a teaching staff would be enormous. If of a

staff of 65 you said, ‘Those seven teachers are really doing well, by whatever

measure,’ then what does that do to the rest of the staff? The product—a

student’s success—this year is attributable to the teacher of the year before,

the year before, the year before and the year before, not the person in front

of the class now.[27]

6.47

Of more significance is the point that teachers will need to have

confidence in the integrity of the system. Teachers are not to be compared with

stockbrokers or FOREX dealers: they are team players. Stated below is one

commonplace suspicion:

I feel very uneasy about [performance pay] because I know how

performance, whether it is in education or in industry at the other end of town,

can be manipulated. You can cook the books and look as if you are an absolute

whiz-bang when really there is no substance there. The other thing too ...is

that—and I saw this when they introduced performance pay [in Victoria]—other

people ride on the backs of their colleagues.[28]

6.48

The committee considers that concerns raised about the effect of

performance pay on secondary school departmental work teams, which operate on

the basis of strong collegiality, are matters that need to be treated

seriously. There is potential for individual performance pay to create

considerable tension in school communities, and lead to a serious loss of trust

and collegial spirit. This would damage rather than enhance teaching quality.

The committee believes that work needs to be done to develop credible group

performance bonus pay schemes which reward team effort and acknowledge esprit

de corps. Nevertheless, the committee believes that the difficulties

associated with introducing a performance based pay scheme can be overcome.

6.49

Another perspective on performance reward was raised in evidence from

the Association of Independent Schools of Western Australia (AISWA). AISWA

argued that quality teachers should be rewarded in a manner which re-invests in

the individual teacher and the teaching profession, for example, professional

development opportunities, teacher exchange and industry work experiences, or payment

of Higher Education Loan Program (HELP) fees for higher qualifications.[29]

Some of these schemes have been operating for many years, but should have been

more extensively offered.

6.50

Dr Ingvarson and his team expressed the view that successful

implementation of performance-based pay schemes for individual teachers is

unlikely to become a reality without the backing of a major research program to

develop the capacity to measure teacher knowledge and skill. It is unlikely

that teachers will become favourably disposed to such a scheme unless it

involves them and their professional associations. This is already beginning.

Several teacher professional associations, notably the National Council for the

Teaching of Mathematics, have developed a set of teaching standards which might

mark the way for future acceptance of performance-based pay schemes. The

committee believes that the teaching profession will need to take this at its

own pace. That way it has more chance of success in achieving the aim of

revitalising the profession.

Conclusion

6.51

Excellence in teaching must be encouraged by all reasonable means. This

is as important for the quality of education throughout Australia as it is for

the vitality of the teaching profession. The inquiry has found that higher

remuneration and some form of performance pay would be instrumental in

enhancing the quantity and quality of the teaching profession.

Recommendation 7

That the Government takes steps to improve the remuneration of

teachers so as to raise the profession's entry standards and retention rates by

providing incentives.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page