Consistency across sectors

3.1

This chapter examines evidence put to the committee on the need for

consistency of whistleblower protections in Australia. After summarising the

whistleblower legislation that is currently in place, the fragmentation and

areas of inconsistency in the legislation are then discussed. Suggestions put

to the committee are then considered along with possible limitations including

the need for flexibility in some areas and potential constitutional

limitations.

Legislation currently in place that relates to whistleblowers

3.2

This section lists the legislation that relates to whistleblowers. While

not exhaustive, the list below indicates there may be over 20 different statutes

relating to whistleblower protection at a federal, state and territory level, as

well as the protections that may apply to informants in the law enforcement

sector. The following public sector legislation applies to whistleblowers in

Australia:

- PID Act;

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 2012 (ACT);

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 2008 (NT);

- Public Interest Disclosures Act 1994 (NSW);

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 2010 (QLD);

- Whistleblowers Protection Act 1993 (SA);

- Public Sector Act 2009 (SA);

- Public Interest Disclosures Act 2002 (TAS);

- Protected Disclosure Act 2012 (VIC); and

- Public Interest Disclosure Act 2003 (WA).[1]

3.3

At the Commonwealth level alone there are already six statutes covering

private sector whistleblowing in Australia:

- Banking Act 1959;

- Life Insurance Act 1995;

- Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993;

- Insurance Act 1973;

- Part 9.4AAA of the Corporations Act; and

- Part 4A of the FWRO Act.[2]

3.4

The Law Council also identified other legislation which may protect

whistleblowing activities including:

- legislation directed at official corruption, such as:

- Independent Commission Against Corruption Act 1998 (NSW);

- Commissions of Inquiry Act 1950 (QLD);

- Corruption and Crime Commission Act 2003 (WA); and

- public administration legislation, such as:

- Public Service Act 1999 (Cth);

- Public Sector Management Act 1994 (ACT);

- Whistleblowers Protection Act 1994 (QLD); and

- State Service Act 2000 (TAS).[3]

Fragmentation of, and inconsistencies in, current legislation

3.5

Several submitters and witnesses drew the committee's attention to the fragmented

and inconsistent nature of current whistleblower protection legislation in

Australia. These submitters pointed, firstly, to the difficulties that can

arise for both whistleblowers and businesses from a fragmented legislative

approach, and secondly, to the potential benefits for both whistleblowers and

businesses of a more coherent and consistent legislative approach.[4]

For example, the AICD argued:

The effect of this fragmentation makes the framework

difficult for whistleblowers to access, interpret and rely on, and for

businesses to understand their obligations.

There is a significantly broader range of corporate

misconduct that should be incorporated into one cohesive framework, thereby

extending protections further and creating greater opportunity for information

about corporate wrongdoing to come to light.[5]

3.6

Similarly, the Law Council argued that the current system failed to

provide clarity and consistency for either whistleblowers or business, and

failed to provide safety for whistleblowers.[6]

3.7 The Law Council also drew attention to inconsistencies in Australia's

public and private sector whistleblower protections, including:

- the limited protections that appear to be available for tax

whistleblowers;[7]

- the protections that typically apply at a state level to

disclosures about wrongdoing by members of parliament, ministerial advisers or

the judiciary that do not attract protections at a federal level;

- the protections that apply at a federal level to public servants

who blow the whistle to the media that may incur liability to criminal or

disciplinary actions in some states; and

- the lack of protections for disclosures about wrongdoing by an

intelligence agency or intelligence operations.[8]

3.8

The Law Council also pointed to various shortcomings under current

statutory protections for corporate whistleblowers enacted in 2004 and

contained in the Corporations Act, such as the criteria that need to be met in

order for a person to qualify for whistleblower protections, including in

regard to who can make a disclosure and to whom:

These criteria can give rise to significant gaps in

protection; for example, anonymous whistleblowers are not protected, and

disclosures made under the Corporations Act can only be made regarding

corporate law, not tax or any other law.[9]

3.9

The committee also heard from regulators about issues arising from

whistleblower protections currently being located in different Acts. For

example, the Australia Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) informed the

committee that it had concerns about the number of different whistleblower

protections schemes at the Commonwealth level, noting that at least five

schemes have been used by whistleblowers in recent years to bring issues to the

ACCC.[10]

3.10

Mr Warren Day, Senior Executive Leader from ASIC noted that the

whistleblower protection provisions under the Corporations Act, the FWRO Act

and the proposed provisions for tax whistleblowers do not necessarily align. Yet,

Mr Day pointed out that it is entirely possible that circumstances could arise

where reportable conduct could relate to two or three separate pieces of

legislation that had inconsistent criteria for disclosable conduct and related

protections.[11]

Inconsistencies in whistleblowing processes and practice

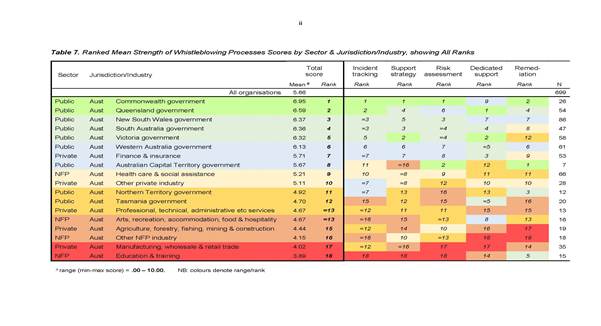

3.11

Legislation provides the foundation for many other aspects including

whistleblowing process and practice. As set out in Chapter 2 of this report, in

May 2017 Professor A J Brown and his colleagues reported on their survey on the

strength of organisational whistleblowing processes and procedures in Australia

which was conducted as part of the Whistling While They Work 2 research

project. Table 3.5 summarises the results.

Table 3.1: Strength of

whistleblowing processes by sector & jurisdiction / industry

Source: A J Brown and Sandra A

Lawrence, Strength of Organisational Whistleblowing processes – Analysis

from Australia, May 2017, p. ii.

3.12

The results of the survey identify a great deal of variation in

the strength of whistleblowing processes across industry sectors as shown in

Table 3.5. While many things will contribute to inconsistencies in

whistleblowing processes across organisations, the task of achieving

consistency is made much harder if the underlying legislation is fragmented and

inconsistent.

Achieving consistency across sectors

3.13

In December 2016, Australia's First Open Government National Action

Plan 2016–18 was finalised. The government's action plan includes a

commitment to harmonise public and private whistleblower protections:

Australia will ensure appropriate protections are in place

for people who report corruption, fraud, tax evasion or avoidance, and

misconduct within the corporate sector.

We will do this by improving whistle-blower protections for

people who disclose information about tax misconduct to the Australian Taxation

Office. We will also pursue reforms to whistle-blower protections in the

corporate sector, with consultation on options to strengthen and harmonise

these protections with those in the public sector.[12]

A single private sector Act

3.14

There was broad agreement amongst witnesses on the need for a single

whistleblower protections Act to cover the private sector, with many submitters

and witnesses noting that this would be of benefit to both potential

whistleblowers and businesses.

3.15

The ACCC was in favour of a single, comprehensive national whistleblower

scheme.[13]

Likewise, ASIC also argued for a single piece of legislation that applies more

universally.[14]

3.16

Professor A J Brown informed the committee that Australia had more scope

to move to a single Act than some other countries:

From a business regulatory point of view, we are in a

position where we can do that, whereas the United States cannot because there

is no federal employment law governing business in effect in the United States.

However, obviously in Australia, especially since Work Choices and under the

current Fair Work type regime that we enjoy, it means that the Commonwealth is

in a position to legislate comprehensively for all corporations and all

employers who are corporations and employees of corporations.[15]

3.17

Noting that whistleblower protections in the United States currently

span 47 different pieces of legislation, Professor Brown pointed out that

the limited progress on corporate sector whistleblowing protections in Australia

to date meant that Australia still has an opportunity to combine whistleblower

protection legislation for the private sector into a single Act.[16]

3.18

Dr Vivienne Brand informed the committee that the current whistleblower

protections in Part 9.4AAA of the Corporations Act are inadequate, and as a

consequence, rarely used. Dr Brand therefore supported ASIC's suggestion of a

single, essentially, private sector whistleblowing Act, noting that future

reviews could always recommend the incorporation of additional elements in the

legislation.[17]

3.19

Nevertheless, in terms of combining whistleblower protections for the

private sector into a single Act, Dr Brand and Dr Sulette Lombard indicated

that there would need to be amendments to a range of provisions to ensure synchronisation

between the FWRO Act protections and the corporate regulatory regime. For

example, in relation to persons who may make an application, the categories

specifically mentioned in the FWRO Act whistleblower protections would not

necessarily be appropriate in the context of corporate whistleblowing.[18]

3.20

Professor Brown set out a potential path for bringing the private

(including tax) and not-for-profit sectors into a single piece of whistleblower

protections legislation, based on the corporations power as well as other heads

of power:

- the main framework;

- categories of disclosable

wrongdoing;

- investigative and regulatory

agencies involved (including ASIC, the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits

Commission, ACCC, APRA, Environment Australia, ROC, the Australian Taxation Office,

AFP etc);

- main protections and duties

on employers/companies, including provisions for the making of regulations and

codes of practice to assist employers;

- provisions and procedures for

bounty/penalty recovery, across all Commonwealth recovery avenues;

- circumstances for third

party/media disclosures;

- relations with State agencies;

- establishing and empowering

the oversight agency; and

- review and oversight.[19]

3.21

The AICD was of the view that a single standalone Act for the private

sector would be of benefit to both potential whistleblowers and businesses. The

AICD argued that a whistleblower cannot be expected to be an expert on the

Corporations Act and that they should not have to consult a piece of

legislation before they make a report. If a whistleblower is a witness of

serious corporate wrongdoing, they should feel confident in making a disclosure

to their company or to an appropriate regulator, without fear that it might

fall outside the definition because of a technicality.[20]

3.22

DLA Piper noted that a single corporate sector Act would provide

whistleblowers with increased certainty and ensure a more consistent approach

to the handling and investigation of disclosures. DLA Piper suggested that it

would be preferable to have all whistleblower protection laws, insofar as they relate to the corporate sector, within a single Act.[21]

3.23

The GIA also supported broadly based standalone legislation for

whistleblower protections:

The institute is very supportive of the provisions in the

Public Interest Disclosure Act serving as a starting point for standalone

whistleblowing legislation applying to the private sector, particularly the

wide coverage of the misconduct it covers and the disclosers it applies to.

Provisions affected by the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Amendment Act

in relation to whistleblowers should also be considered. The institute is very

much in favour of standalone legislation rather than recommending multiple

reforms to multiple pieces of legislation.[22]

3.24

The Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees (AIST) supported the

use of the principles in the Breaking the Silence Report[23]

in new stand-alone legislation to replace whistleblower provisions across

several private sector Acts and the charity sector. The AIST also informed the

committee that:

We would support one piece of national legislation that

covers the field. It would certainly make it easier for whistleblowers to

understand what their rights and obligations are. Also, as

one piece of legislation is amended, others are not necessarily, so there could

be differences in standards. As people move between industries, they may not be

aware of what the possibilities are for making disclosures and what the different

protections might be that are offered.[24]

3.25

The Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance (MEAA) also supported

consolidated public and private sector whistleblower legislation.[25]

3.26

Ms Serene Lillywhite, Chief Executive Officer of Transparency

International argued that there should be flexibility within a private sector

legislative scheme to account for differences in the size and nature of private

sector organisations because the size of the corporation may impact on the

level of protection that can be provided:

So there needs to be some flexibility with regard to

considering the level of protection that may be required and the process of

reporting that may be required. That depends on the size and scope of the

corporate entity and depends on where within the supply chain or the value

chain of the business the alleged misconduct has taken place. All of those

things may be important considerations in terms of designing a mechanism to

ensure there is some flexibility to bring about a response that is appropriate for

the misconduct that has been reported.[26]

3.27

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of the Ethics Centre also argued

for some flexibility for the private sector and did not support legislation

that would set out precise measures that corporations had to employ in

addressing whistleblowing issues.[27]

A single Act for the public and

private sectors

3.28

While there was general agreement amongst submitters and witnesses on

the need to harmonise, as far as possible, whistleblower protection provisions

across the public and private sectors, several witnesses pointed to the need to

take account of the differences between public and private sector organisations

in designing legislative approaches, as well as recognising areas where the

current public sector provisions could be improved to meet best practice

criteria.

3.29

By contrast, the IBACC informed the committee that in its view there

should be one Commonwealth statute covering the field for private and

not-for-profit sector whistleblower protections:

The [IBACC] strongly believes that it is desirable for

consistency and for transparency across the private and not-for-profit sectors

that the whistleblower protection laws should be consistent and the same. It

would, in the [IBACC]'s opinion, be detrimental to the success of any reforms

if different protection regimes applied to different sectors in the country or

in different industry sectors. That position is only likely to highlight a risk

that a genuine whistleblower may, depending upon the conduct in question, fail

to be properly protected if he or she does not fit neatly into a narrow,

industry or sector focused definition.[28]

3.30

Ms Rebecca Maslen-Stannage, Chair of the Corporations Committee, Law

Council told the committee that the Law Council supported harmonised reforms to

whistleblower protections. The Law Council saw that there would be value in

combining public and private sector legislation into a single Act in order to

maintain consistency between the two sectors:

...the Law Council

supports harmonised reforms to other existing whistleblower protections such as

improved protections for public sector whistleblowers as well as those

contained in the Corporations Act either by amendment to each relevant act or

by introduction of overarching whistleblower legislation.[29]

3.31

Importantly, the Law Council also stressed the importance of harmonising

federal, state, and territory laws:

More broadly, the Law Council considers it is vital that any

regime introduced is uniform across the board, with a view to having states and

territories adopting a similar or parallel approach through collaboration with

the Council of Australian Governments and that it be built on a sound

foundation of the culture of corporate compliance, as is already promoted by

relevant provisions of the criminal code. Perhaps to highlight the key points

in our submission, the Law Council's view is that the laws should be uniform in

structure and operation, applying across all contexts and sectors. The law

should apply to any whistleblower without regard to narrow specifications of

relationship to the entity in question.[30]

3.32

ASIC Commissioner, Mr John Price, told the committee that while ASIC

considered it desirable to align whistleblowing approaches across the

not-for-profit, public and corporate sectors, there might be some benefit in

having slightly different approaches between the public and private sectors to

account for the different nature of the organisations that operate in those

sectors.[31]

3.33

Ms Lillywhite from Transparency International noted that in order to

harmonise public and private sector whistleblower protections, it would be

necessary to reform the public sector protections first:

...we note that given improvements to that act are required to

meet international best practice, and the need for greater flexibility in the

implementation of protection across the private and not-for-profit sectors, we

believe this harmonisation objective is unlikely to be useful, at least in the

short-term.[32]

...the existing public sector protection is not at a high

enough standard and is not robust enough. So we would not want to harmonise

with something we believe is not yet at best practice standards.[33]

3.34

Transparency International also argued that the public sector should be

subjected to higher levels of accountability and therefore there may need to be

differences between the public and private sector acts:

TI [Transparency International] Australia considers that as a

general principle a one-size-fits-all approach designed to work for the public

sector—even when that is brought up to a higher standard—should not necessarily

be imposed on the private and not-for-profit sectors. It is

our view that public officials have a heightened responsibility to uphold the

principles of transparency and accountability.[34]

3.35

DLA Piper argued that public and

private sector whistleblower legislative regimes should remain separate but be

harmonised where appropriate:

In principle, we are in

favour of harmonisation of whistleblower provisions across the public, corporate and not-for-profit sectors. Harmonisation has the benefit of reducing

confusion and increasing confidence for whistleblowers, these sectors and regulators...we

consider

that there are provisions of the ROC amendments which could be usefully adapted for the corporate sector.[35]

3.36

DLA Piper also suggested that the details of internal whistleblower

programs could be left to guides developed and provided by regulators:

We have suggested, instead, that it would be beneficial for

ASIC, and, indeed, other regulators, to offer regulatory guidelines which offer

best practice principles which internal programs could reflect. They could also

be incentivised by an offering of a reduction in liability in circumstances

where internal programs do in fact reflect such features, and perhaps other

conditions as well.[36]

3.37

With respect to a single piece of whistleblower legislation for both

the public and private sectors, Dr Lombard noted that corporate behaviour can

be influenced in a number of ways through statutory disclosure requirements

that would not necessarily operate in the same way in the public sector. She

therefore expressed concern that a single whistleblowing Act may struggle to

cope with the differences between public and private sector entities:[37]

It would be necessary for it to have to be framed in broader

terms than you would be able to do for particular sectors. Once again, it comes

down to the drafting and paying careful attention to what you actually want to

achieve by the legislation. In my view, it is all about making sure that people

with information come forward. If you adopt that as a central focus and build

the regulation around that, hopefully it could succeed.[38]

3.38

Likewise, Dr Brand informed the committee that she considered it would

not be appropriate to try to combine public and private sector whistleblower

protections into a single Act:

As nice as it would be to have an office of the whistleblower

and one act, and we are done, I do not think it works that way. The corporations

power will get you a fair part of the way with the big money, with the

corporations which do the things that cost the economy a lot of money. And

there will be other powers that might get you there with other things like the

fair work amendments. It probably will not be a beautiful neat system but then

our regulatory system for corporations already is not and for most things is

not.[39]

3.39

Similarly, Professor Brown indicated that it is really important to

articulate the principles that should be common across the public and private

sectors, while noting that areas of difference may include thresholds and

requirements for procedures that would be imposed on the private sector.

Professor Brown also argued for:

...a high level of consistency and with both of them being

clear on when they are relying on the Fair Work Act and the existing employment

and civil remedies for enforcement of the legislation. I think there is a real

need for the government to look at making sure that its reform of the Public

Interest Disclosure Act and the new legislation are as consistent as possible,

but I do suspect that they are going to still end up being two pieces of

legislation.[40]

3.40

The AFP was of the view that while consistency across sectors is

desirable, whistleblowing in a public sector context raises separate issues requiring

specific consideration. The AFP suggested that any harmonisation of

whistleblower protections at a Commonwealth level should take into account the

relationships between regulatory and criminal misconduct, and the need to

support interagency partnerships so wrongdoing can be addressed in the most appropriate

manner.[41]

3.41

The AFP also informed the committee that the Criminal Code applies to

the public, private and not-for-profit sectors equally:

From a law enforcement investigative perspective, the AFP is

not concerned with the type of sector in which wrongdoing occurs, or whether it

is committed by an individual, corporation or not-for-profit body. The AFP is

only concerned as to the type of wrongdoing which has been committed: that is,

whether it involves a breach of Commonwealth criminal law. As noted above, the

AFP's priorities relate to complex, transnational, serious and organised crime,

and include serious financial crime.[42]

Constitutional limitations

3.42

One of the issues that arose during the inquiry concerned the extent of

the Commonwealth's power to legislate for whistleblower protections across the

private sector.

3.43

The Parliamentary Library summarised potential constitutional

limitations on the Federal Parliament in a research note on whistleblowing in

Australia:

The Federal Parliament lacks a general power to implement

comprehensive whistleblower legislation covering the public and private

sectors. However, the Federal Parliament has used its constitutional powers to

provide for whistleblower protection mechanisms in specific areas. For example,

it used its corporations power (paragraph 51(xx) of the Constitution) to

legislate a framework to encourage whistleblowing in relation to suspected

breaches of the Corporations Act. This legislation applies to any 'constitutional

corporation', that is, any incorporated body.

To reach unincorporated associations including charities,

which otherwise are under state jurisdiction, the Commonwealth could, for

example, use the taxation power (paragraph 51(ii) of the Constitution). With

respect to charities, the government could prescribe that tax exemptions may

only be available if internal whistleblower protection standards such as AS

8004 are established, or if the charity became part of an external

whistleblowing scheme.[43]

3.44

The Parliamentary Library research note suggested that comprehensive and

fully uniform legislation would require either cooperation between the states

to enact uniform legislation or the referral of power from the states to the

Commonwealth under paragraph 51(xxxvii) of the Constitution.[44]

3.45

In 1994 the Senate Select Committee on Public Interest Whistleblowing encouraged

the states, territories and industry to work with the Commonwealth to address

areas of Commonwealth constitutional limitations in relation to private sector

whistleblowing, including consideration of an industry ombudsman.[45]

3.46

The 1994 Select Committee received information from the

Attorney-General's Department that the Commonwealth Parliament could legislate

to protect whistleblowers under the following heads of power in the Commonwealth

of Australia Constitution Act 1900:

Section 51(xx), the corporations power, would support a law

which empowered a Commonwealth body to investigate and report on the activities

of a foreign, trading or financial corporation;

Section 61, the executive power, would support a law in

respect of whistleblowing which relates to breaches of a Commonwealth law, and

Section 51(xx), the express incidental power, would support laws giving the

Commonwealth body the requisite investigative and reporting powers.[46]

3.47

Dr Brand advocated using the corporations power because the vast

majority of Australian businesses are run through a corporation. Dr Brand also

suggested that:

You might then go via other heads of power for any gaps that

are left. But if you divide whistleblowing regulation into private versus

public—and we would say put not-for-profit somewhere in the corporate power

basket but that does get messy because of the lack of constitutional

support—then you have pretty much taken care of it, I think.[47]

3.48

The Law Council argued that whistleblower legislation should be as broad

as possible in its coverage and:

- if gaps arise due to constitutional limitations, there may need

to be complementary laws across the Commonwealth, states and territories; and

- the legislation should be uniform and the approach across the

Commonwealth, states and territories should be parallel.[48]

3.49

The Law Council provided further suggestions for establishing an

appropriate constitutional basis for whistleblower protections:

Generally the constitutional basis for whistleblower laws

will be the head of power that underpins the principle legislation, on the

basis that such laws are reasonable incidental to the primary law. The

Commonwealth can go into the legislation that provides the relevant offence in

respect of which the whistle in being blown. Hence for corporations it would go

into the Corporations Law and be supported by the heads of power that support

that law, namely the corporations' power and the referral of power by the

States.[49]

Committee view

3.50

The vast majority of the evidence to the committee strongly supported

greater consistency and harmonisation across public and private sector

whistleblower protection legislation, including combining all private and

not-for-profit sector whistleblower protection legislation into a single Act.

3.51

While some submitters argued that the public sector should be subject to

a greater degree of accountability, the committee notes that following the

privatisation of services previously provided by the public sector, as well as the

greater use of outsourcing, the private sector now plays a significant role in

providing public services and these privately-provided services should have

appropriate accountability.

3.52

To this end, the committee considers that there is much to be gained

from consistent and harmonised whistleblower legislation, including:

- keeping the process simple for whistleblowers and avoiding

whistleblowers being repeatedly referred from one body to another;

- ensuring that businesses which provide public services directly

or through contracts to public sector bodies are not subjected to inconsistent

legislation;

- reducing regulatory compliance burdens on business; and

- making it easier and more efficient for the body of legislation

to be maintained into the future.

3.53

The weight of evidence to this inquiry did not favour combining public

and private whistleblower protections into a single Act. The committee is not

averse to further exploration of appropriate ways to combine public and private

sector legislation into a single Act. On balance, however, the committee

considers that the Commonwealth public sector whistleblower protections should

be retained in a separate single Act at the present juncture.

3.54

There was broad support for a single Act to capture all private sector

whistleblower protections, with submitters and witnesses pointing out that this

would not only provide a much clearer framework for whistleblowers and businesses

alike, but would also reduce regulatory compliance burdens on business.

3.55

In this regard, the committee notes that, in a previous Parliament, it

endorsed the creation of a single piece of whistleblower legislation for the

private sector that would be consistent with public sector whistleblower

protection schemes:

Indeed the longer term solution may be found in the

development of a more comprehensive body of whistleblower protection law that

would constitute a distinct and separate piece of legislation standing outside

the Corporations Act and consistent with the public interest disclosure

legislation enacted in the various states.[50]

3.56

The committee therefore reiterates its continuing support for a single

Act to combine all private sector whistleblower protections.

3.57

Furthermore, the committee notes the evidence presented in this chapter indicates

that it may be constitutionally possible for a single Act to combine all

private sector whistleblower protection, even if multiple heads of power are

needed.

3.58

While the committee considers it preferable to have separate

whistleblower protection legislation for the public and private sectors, the committee

recommends that the government explore mechanisms to ensure the ongoing

consistency between the public and private sectors, including examining the

potential to maintain both public and private sector whistleblower protections

in a single Act. In this regard, the committee notes the example of the Privacy

Act 1988, which sets out the Australian Privacy Principles that apply to

Australian government agencies, all private sector and not-for-profit

organisations with an annual turnover of more than $3 million, all private

health service providers and some small businesses.[51]

3.59

The committee considers that many of the best practice criteria for

whistleblower protections could be aligned across the public and private

sectors, while for other criteria the principles could be the same, but the

details may need to differ. The committee has set out some suggestions for each

best practice criterion in Table 3.2 below.

Recommendation 3.1

3.60

The committee recommends that:

-

Commonwealth public sector whistleblowing legislation remain in a

single updated Act, redrafted in parallel with the private sector Act;

-

Commonwealth private sector whistleblowing legislation (including

tax) be brought together into a single Act;

-

The Government examine options (including the approach taken in

the Privacy Act 1988) for ensuring ongoing alignment between the public

and private sector whistleblowing protections, potentially including both in a

single Act; and

-

The Commonwealth, states and territories harmonise whistleblowing

legislation across Australia.

3.61

The following provides an explanation for reading table 3.2:

- Column 1 sets out the best practice criteria for whistleblowing

legislation;

- Column 2 indicates the best practice criteria where the amended

public sector legislation and the new private sector legislation could be

aligned; and

- Column 3 indicates the particular aspects of the best practice criteria

where the new private sector legislation would differ from that in the public

sector.

Table 3.2: Potential differences similarities between new

public and private sector legislation.

| Best Practice Criteria for

Whistleblowing Legislation |

Could be the

same |

Private sector differences |

| 1 |

Broad

coverage of organisations |

No |

Privacy

Act definitions |

| 2 |

Broad

definition of reportable wrongdoing |

No |

Limit

to a breach of a Commonwealth or state or territory law. |

| 3 |

Broad

definition of whistleblowers |

No |

Take

account of different organisational structures and regulatory arrangements. |

| 4 |

Range

of internal / regulatory reporting channels |

No |

Take

account of different organisational structures and regulatory arrangements. |

| 5 |

External

reporting channels (third party / public) |

Yes |

|

| 6 |

Thresholds

for protection |

Yes |

|

| 7 |

Provision

and protections for anonymous reporting |

Yes |

|

| 8 |

Confidentiality

protected |

Yes |

|

| 9 |

Internal

disclosure procedures required |

No |

Requirements

are appropriate for the private sector. |

| 10 |

Broad

protections against retaliation |

Yes |

|

| 11 |

Comprehensive

remedies for retaliation |

Yes |

|

| 12 |

Sanctions

for retaliators |

Yes |

|

| 13 |

Oversight

authority |

Yes |

Different

oversight authority for public and private sectors. |

| 14 |

Transparent

use of legislation |

Yes |

Likely to require different reporting arrangements

involving regulators. |

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page