Background

Introduction

2.1

This chapter provides the context for the current inquiry. It begins by summarising

the arguments put to the committee on the value and importance of establishing

effective whistleblower protections. It then notes the current legislative

framework that applies to the public sector, to registered organisations, and

to the corporate sector. This is followed by an overview of various

whistleblower inquiries that have occurred in Australia since the early 1990s

and the development of whistleblower legislation during that period. The

following section sets out some of the international developments in

whistleblower protection legislation as part of greater global moves to tackle

corruption. The chapter finishes with an analysis of Australia's current

whistleblower protection legislation as measured against specific best practice

criteria.

Context—why whistleblowing is important

2.2

The key arguments for establishing effective whistleblower protections are

essentially based on a view put by numerous submitters and witnesses that

whistleblowing was critical in fostering a culture of transparency,

accountability, and integrity. For example, Ms Serene Lillywhite, Chief Executive

Officer, Transparency International indicated that:

- whistleblower protection is integral to fostering transparency,

promoting integrity and detecting misconduct;

- protecting whistleblowers promotes a culture of accountability

and integrity in both the public and private institutions; and

- whistleblowing empowers citizens against corruption and

encourages the reporting of misconduct, fraud and corruption.[1]

2.3

Mr Jordan Thomas pointed out that whistleblowers perform a vital service

to both markets and organisations because:

- they force us to focus on our failings;

- they challenge our ideals; and

- they show the limits of law enforcement authorities,

self-regulatory organisations, and corporate compliance programs.[2]

2.4

As discussed below, several submitters and witnesses argued that a strong

whistleblower culture would have a positive transformative impact on

organisations by helping to drive organisational change from within.

2.5

For example, the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD) argued

that boards and directors have a critical role to play in establishing and

promoting a corporate culture that supports disclosure of wrongdoing:

...a speak-up culture within organisations. And this is very

much an issue that is top of mind for Australian directors and is very much

raised in the forums and committees with our members that we work with. We

believe the regulation of whistleblowing has a significant impact, as well, on

that culture of disclosure. The inadequacies in the current system limit the

ability of corporates, directors and whistleblowers to play their part in

ensuring the compliance of organisations with the law as a whole.[3]

2.6

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director of the Ethics Centre argued that

it would be useful to draw a distinction between the reporting of wrong doing

as an ordinary regular practice and whistleblowing as a more extraordinary

event. The Ethics Centre argued for creating cultures in which it is entirely

normal for a person to spot a discrepancy between what the organisation says it

stands for and what it is actually doing, or to spot some element of risk

either to the corporation or to other people who have a legitimate interest in

the corporation's conduct. Viewed in this light, the Ethics Centre suggested

that whistleblowing should be seen as an extraordinary event where a person is

required to go outside the bounds of the organisation and its normal channels

in order to raise serious concerns about some aspect of the corporation's

conduct, or somebody associated with that corporation.[4]

2.7

In a similar vein, Mr Warren Day, Senior Executive Leader from the

Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) argued that a good

organisational culture should reduce the need for whistleblowers and that the

presence of a whistleblower indicated a failure of organisational culture and

compliance systems.[5]

2.8

Likewise, Mr Phil Ware, Member of the Association of Corporate Counsel Australia

took the view that whistleblower protection legislation should be designed to

encourage proactive internal compliance procedures:

The regulatory goal should not so much be a more effective

framework for corporate whistleblowing which is focused on punishment of

offenders, which is lagging and punitive, let alone the windfall enrichment of

whistleblowers and their lawyers via bounties in circumstances where they are

immune from costs. The regulatory goal, rather, should be improving the

effectiveness of internal compliance cultures. This is leading, proactive and

preventive.[6]

2.9

Mr Joshua Bornstein, Director/Principal from Maurice Blackburn Lawyers informed

the committee of his concerns about sub-standard corporate governance in

Australia:

I think there is a fundamental problem in Australian business

culture, which is that its corporate governance standards are poor. This

malaise feeds I think also into our political, legislative and regulatory

culture. There have been countless scandals in our banking and finance sector

in the last decade involving illegal and improper conduct. Many thousands of

consumers, including vulnerable retirees, have been ripped off. Wage and

superannuation fraud is now, in my experience, at an unprecedented level,

particularly impacting low-paid and vulnerable employees right across the

private sector. Bribery scandals regularly dog Australian companies trading

overseas, and company tax compliance in this country is a rolling scandal.[7]

2.10

Mr Thomas asserted that corporations serve a necessary social purpose

but can also cause great harm. He was of the view that encouraging those who

know of wrongdoing in

the workplace to speak out is essential to protecting the innocent

victims of such misconduct.[8]

2.11

However, Mr Thomas also pointed out that being a corporate whistleblower

is rarely easy or glamorous and can often involve great risk for the person

speaking out. Mr Thomas explained why reprisals occur even when it is not in

the corporation's best interest:

In agency theory it is recognized that there is an inherent

potential for conflict between the interests of an entity and the interests of

its agents – the ones who act for the company. So while a 'company' may

logically have an interest in acting legally and ethically, and in encouraging

its employees to report misconduct without fear of retaliation, its managers

and officers, as agents, may not share this corporate interest...The 'corporation'

may have no interest in harming the whistleblower, but the corporation can only

act through its agents. History, and countless surveys and media stories,

consistently show that those agents can and do retaliate against corporate

whistleblowers.[9]

2.12

Ms Julia Angrisano, National Secretary from the Financial Sector Union

(FSU) informed the committee that the feedback it received from its member

surveys indicates that workers lack trust in the current frameworks and

policies across the industry because they have experienced, seen or heard

practices that suggest a significant gap between policy and practice for

whistleblowers. The FSU gave some examples of the feedback that it had

received:

When we asked the reason for not accessing whistleblower

policies, many of our members told us that it is made very clear to them that

they should not rock the boat by calling out bad behaviours or that the system

rewards people who do what they are told. Often, they talk to us about the fact

that their pay system sometimes rewards them for selling an insurance policy or

another financial product that is worse than the current policy, but that is

the framework that they operate within.[10]

Our members contact us feeling like they have seen something

or they have heard something, but they are too scared to raise it, because they

have seen it happen in other circumstances where people just simply lose their

jobs or move on to another department or are isolated.[11]

2.13

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) informed the committee that whistleblowers

are important in detecting serious financial crime that is often sophisticated,

well concealed, and part of a culture of cover-up. The AFP noted that due to

the complex nature of serious financial crime there is often a low risk of

discovery by regulators and law enforcement unless whistleblowers are supported

in coming forward. The sorts of matters where whistleblowers may inform

investigations include foreign bribery, serious tax crime, identity crime,

corporate and government corruption matters and serious fraud offences. The AFP

argued that:

If people are discouraged from coming forward to regulators

or law enforcement due to lack of protections for their safety, protection from

legal action and the personal and financial impacts of disclosing company

information, there may be no case to prosecute. Where people do come forward,

but are not willing to give evidence, due to lack of protection for anonymity,

law enforcement may not have sufficient evidence to prosecute. This may not be

fixed solely by enhancing protections as court procedures can only go so far in

protecting witness identity.

Whether or not improved whistleblower protections would

encourage people to come forward and disclose wrongdoing would depend on how

the system is framed, and whether the public has the confidence that the system

can ensure any protections.[12]

2.14

The Governance Institute of Australia (GIA) argued that whistleblowing

has a critical role to play in identifying and stopping misconduct in the

corporate sector, but it is only one aspect of companies' overall programs to

ensure compliance with regulation and to prevent and detect misconduct:

Whilst we do not consider that misconduct and illegal

activity is endemic within Australian companies, our members' experience is

that whistleblowing usually occurs when other avenues that already exist have

been exhausted or failed. Again, we note our support for significant reforms in

this area.[13]

2.15

The International Bar Association Anti-Corruption Committee (IBACC) argued

that, from the submissions to this inquiry, it appeared that those who blow the

whistle outside of the public sector do so at their own risk and at their own

peril:

There have been numerous reports, inquiries and research done

over the years that have looked at this question, and yet still the messenger

and the message are attacked, and the underlying conduct seems not to be

addressed or, if it is addressed, it is addressed privately and out of the

public spotlight.[14]

Protections in the private sector have generally been

non-existent...Whistleblowers face a large number of severe sanctions on and

processes of adverse consequences for them. They are real, they are emotional

and financial, and they can affect people for many years thereafter, when all

they were doing, invariably, was their job, by reporting something that they

observed to the company by which they were employed, and they, in turn, became

the target of an attack—from the company or from those engaging in the

behaviour—to suppress it.[15]

2.16

The Law Council of Australia (Law Council) considered whistleblower

protection reform to be urgent. However, the Law Council cautioned that

piecemeal regulation would be insufficient, and that careful policy analysis

was necessary to ensure that regulation led to genuine behavioural and

structural change.[16]

2.17

The AICD argued that legislative reform that took account of best

practice indicators could lead to substantial improvements in Australia's

corporate whistleblowing framework, particularly given the current anaemic

framework.[17]

Public interest disclosure

2.18

Whistleblowing is often technically referred to as public interest

disclosure. Whistleblowers play a critical role in identifying and preventing

misconduct. Legislative protections have existed for public sector

whistleblowers in most Australian states and territories since the 1990s. Protections

for private sector whistleblowers were not legislated until 2004.[18]

Commonwealth public sector

2.19

The Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 (PID Act) is intended to

promote the integrity and accountability of the Commonwealth public sector by:

- encouraging and facilitating the making of disclosures of

wrongdoing by public officials;

- ensuring that public officials who make protected disclosures are

supported and protected from adverse consequences relating to the making of a

disclosure; and

- ensuring that disclosures are properly investigated and dealt

with.[19]

Registered organisations

2.20

In November 2016, the Parliament passed amendments to the FWRO Act which

strengthened whistleblower protections for people who report corruption or

misconduct in unions and employer organisations. The amendments provide

protections to whistleblowers who disclose information about contraventions of

the law, including current and former officers, employees, members and

contractors of organisations.[20]

Amendments that were introduced by the Senate and passed both Houses include:

- defining what constitutes a reprisal;

- civil remedies against reprisals;

- awarding of costs against vexatious proceedings;

- civil penalties for reprisals;

- criminal offences for reprisals;

- that protections have effects despite other Commonwealth laws;

- provisions for the investigation and handling of disclosures;

- time limits for investigations;

- disclosures to enforcement agencies; and

- protection of witnesses.[21]

Corporate whistleblowing

2.21

Current protections for whistleblower disclosures in the corporate

sector are contained in Part 9.4AAA of the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations

Act) which was introduced as part of a range of corporate legislative reforms

in 2004. Those protections:

- confer statutory immunity on the whistleblower from civil or

criminal liability for making the disclosure;

- constrain employer rights to enforce a contract remedy against

the whistleblower (including any contractual right to terminate employment)

arising as a result of the disclosure;

- prohibit victimisation of the whistleblower;

- confer a right on the whistleblower to seek compensation if

damage is suffered as a result of victimisation; and

- prohibit revelation of the whistleblower's identity or the

information disclosed by the whistleblower with limited exceptions.[22]

2.22

For public interest disclosures concerning misconduct or an improper

state of affairs or circumstances affecting the institutions supervised by the

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), whistleblower protections in

the following acts may apply:

- the Banking Act 1959;

- the Insurance Act 1973;

- the Life Insurance Act 1995; and

- the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993.[23]

Previous inquiries and reviews

2.23

In 2005, the Parliamentary Library published a research note on

whistleblowing in Australia. The library noted that whistleblower protections

became a significant issue in the late 1980s and early 1990s when inquiries

identified that the common law was unable to provide employees with a right to

disclose information about the workplace and protection from reprisals.

Following those inquiries, all Australian states and the Australian Capital

Territory (ACT) adopted some form of public interest disclosure protection

legislation.[24]

2.24

In 1991, the Gibbs committee review of Commonwealth Criminal Law

recommended that catch-all secrecy provisions should be replaced with

provisions limiting penal sanction for the unauthorised disclosure of official

information to specific categories required for the effective functioning of

government, such as defence and foreign affairs. The Gibbs committee concluded

that appropriate protections should be provided for disclosure of other

information in the public sector.[25]

2.25

In 1991, the Senate Standing Committee on Finance and Public

Administration concluded that the Commonwealth Ombudsman has often been

unsuccessful in resolving major and complex complaints and made the following

observations in relation to whistleblower protections:

Perceived failings were that the Ombudsman's investigations were ineffectual, that there was no power to

resolve any serious deficiencies which might have been detected or to protect

complainants effectively and that members of the Ombudsman's staff were too

close to the public servants they were sent to investigate.[26]

2.26

This led the committee to make the following conclusions and

suggestions:

...that the Ombudsman should be responsible at least for

filtering whistleblowing complaints or redirecting them if appropriate to

another agency. In some cases it would be necessary for the Ombudsman to

undertake a full investigation into a whistleblowing allegation.

To deal with whistleblowing allegations and to enable the

Ombudsman to fulfil a role as an external review body as outlined above, the

Committee recommended that the Ombudsman establish a specialist investigation

unit within its Office. This new aspect of its operations would also be able to

target areas for systemic reform, but its activities would remain separate from

the bulk complaint work of the Ombudsman because of the different investigative

approach required.[27]

2.27

In 1994, a Senate Select Committee on Public Interest Whistleblowing

acknowledged that whistleblowing is a legitimate form of action within a

democracy. That committee also indicated that national leadership and education

would be required in addition to the legislative changes it recommended,

including:

- the establishment of the public interest disclosure agency to

receive disclosures, act as a clearing house, arrange for investigations,

ensure protection of whistleblowers, and provide a national education program;

- that legislation cover both the public and private sectors;

- that the states, territories and industry work with the

Commonwealth to address areas of Commonwealth constitutional limitations in

relation to private sector whistleblowing, including consideration of an

industry ombudsman;

- that legislation extend to policing, academic institutions,

health care and banking;

- not allowing anonymous disclosures;

- exemption of public interest disclosures from most secrecy

provisions;

- that protection of whistleblowers be conditional on correct

procedures being followed;

- that victimisation of whistleblowers should be investigated;

- that the subject of whistleblowing be protected in accordance

with the principles of natural justice and that false allegations should

constitute an offence;

- that Legal Aid should be available to whistleblowers; and

- that a reward system should not be considered.[28]

2.28

In 1995, another Senate Select Committee examined unresolved

whistleblower cases. There were also several unsuccessful attempts at a federal

level to introduce whistleblower legislation.[29]

2.29

In 2004, this committee considered corporate sector whistleblower

protections as part of its inquiry into the Corporate Law Economics Reform

Program (CLERP) (Audit Reform and Corporate Disclosure) Bill 2003 (CLERP Bill).

At the time the committee noted:

The latest spate of corporate failures has once again

highlighted the problems created by a culture of corporate silence which allows

wrongdoing to go undetected. It has raised public awareness of the crucial role

that personnel can have in uncovering corporate wrongdoing. Most recent studies

into whistleblowing agree that change is needed on two main fronts a cultural

shift in attitudes toward whistleblowers and legislative reforms to both

encourage and maintain this change.[30]

2.30

The committee considered the whistleblower scheme in the CLERP bill to

be 'sketchy in detail', with scant information in the legislation and the

Explanatory Memorandum on the obligations of companies to ensure that they have

in place a whistleblower scheme.[31]

2.31

The committee made a number of recommendations to offer greater

encouragement for whistleblowers to come forward and for companies to

investigate wrong doing, including:

- requiring corporations to establish a whistleblower scheme;

- requiring ASIC to publish guidance notes for companies on

whistleblower schemes;

- clarifying the application of legislation to employees of

contractors;

- replacing the 'good faith' test with 'an honest and reasonable

belief';

- requiring that disclosures are about serious matters;

- providing for anonymous disclosures and confidentiality; and

- allowing ASIC to represent the interest of a person who is

alleged to have suffered a reprisal.[32]

2.32

In 2009, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Legal and

Constitutional Affairs considered public sector whistleblower protections and made

recommendations, including:

- the introduction of legislation for public sector whistleblower

protections;

- rights for people in the public sector to raise concerns without

fear of reprisal;

- a requirement for whistleblowers to act in 'good faith';

- a definition of who is able to be a whistleblower;

- a suggestion for future consideration of whether members of the

public may be able to make public interest disclosures;

- that the Commonwealth Ombudsman be the authority for receiving

and investigating public interest disclosures and for oversight of the public

interest disclosure scheme in the Commonwealth;

- the types of disclosure that should be protected;

- that the motive of the whistleblower should not prevent the

disclosure from being protected;

- that protection not apply to disclosures that are 'knowingly

false';

- that protections include immunity from criminal liability, civil

penalties and certain civil actions;

- obligations for agencies to establish whistleblower protection

procedures;

- provision for disclosure to the media and Members of Parliament;

and

- protection for disclosures to third parties such as legal

advisors, professional associations and unions where the disclosure is made for

the purpose of seeking advice or assistance.[33]

2.33

In March 2013, the Public Interest Disclosure Bill 2013 (PID Bill) was

introduced to the House of Representatives.[34]

It sought to make a number of reforms and bring a new act to replace limited

whistleblower protections that previously existed in the Public Service Act

1999. The PID Bill overlapped with earlier private members Bills on

whistleblower protections introduced by Mr Andrew Wilkie MP.[35]

2.34

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and

Legal Affairs considered both the PID Bill and Mr Wilkie's Bills. That

committee tabled an advisory report in March 2013, recommending that the PID

Bill be passed with amendments to clarify continuity of protection, protections

for external disclosures and protections from reprisals.[36]

2.35

The Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee also

examined the provisions of the PID Bill and made recommendations, including:

- adding protections for disclosure to supervisors;

- clarifying provisions for misleading or false claims;

- clarifying requirements for external disclosures; and

- removing a clause that was ineffective in relation to parliamentary

privilege.[37]

2.36

In its inquiry into the performance of ASIC, the Senate Economics

References Committee made recommendations on whistleblower protections

including:

- broadening the definition of whistleblowers and scope of relevant

information;

- protecting the identity of whistleblowers and anonymous disclosers;

- a review of Australia's framework for protecting corporate

whistleblowers drawing on the 2009 Treasury options paper as appropriate;

- changes to requirements for whistleblowers to act in good faith;

and

- remedies for whistleblowers who are disadvantaged and

consequences for those taking reprisals against whistleblowers.[38]

2.37

The Senate Economics References Committee also published an issues paper

on corporate whistleblowing as part of its inquiry into scrutiny of financial

advice which lapsed at the end of the 44th Parliament.[39]

The committee invited submitters to the current inquiry to comment on the

issues paper.

2.38

In October 2016 the government released the 'Moss Review' of the effectiveness

and operation of the PID Act. The Moss Review found that:

- the PID Act had only been partially successful partly due to its

recent implementation and ineffective operation of the framework;

- the mechanisms under the PID Act which

facilitate investigation of wrongdoing were overly complex; and

- the categories of disclosable conduct

were too broad and should be focussed on the most serious integrity risks.[40]

2.39

The Moss Review made recommendations including:

- strengthening the ability of the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Inspector-General

of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) to scrutinise and monitor the decisions of

agencies, and increasing the number of investigative agencies;

- a greater focus on significant wrongdoing and expanding the

grounds for external disclosure; and

- redrafting the PID Act using a principles-based approach and

better protections for witnesses and whistleblowers.[41]

2.40

In December 2016, Australia's First Open Government National Action

Plan 2016–18 (the action plan) was finalised. The action plan includes a

commitment to improve whistleblower protections in the tax and corporate

sectors as follows:

Australia will ensure appropriate protections are in place

for people who report corruption, fraud, tax evasion or avoidance, and

misconduct within the corporate sector.[42]

We will do this by improving whistle-blower protections for

people who disclose information about tax misconduct to the Australian Taxation

Office. We will also pursue reforms to whistle-blower protections in the

corporate sector, with consultation on options to strengthen and harmonise

these protections with those in the public sector.[43]

2.41

As part of the action plan the government committed to examining the

Registered Organisations Commission (ROC) whistle-blower amendments with the

objective of applying those amendments to the corporate and public sectors:

The Government has committed to supporting a Parliamentary

inquiry (Inquiry) to examine the Registered Organisations Commission

whistle-blower amendments with the objective of implementing the substance and

detail of those amendments to achieve an equal or better whistle-blower

protection and compensation regime in the corporate and public sectors.[44]

2.42

The timetable for government action set out in the action plan is shown

in Table 2.1 below.

2.43

In December 2016, the government established a review of tax and

corporate whistleblower protections in Australia. A consultation paper was

released and submissions were due by 10 February 2017.[45]

Table 2.1: Timetable for

National Action Plan whistleblower commitments

| Milestone |

End date |

| Establish Parliamentary

inquiry. |

30 June 2017 |

| Treasury to release a

public consultation paper covering both tax whistle-blower protections and

options to strengthen and harmonise corporate whistle-blower protections with

those in the public sector. |

March 2017 |

(i) Development and public

exposure of draft legislation for tax whistle-blower protections (informed by

consultation).

(ii) Recommendation to

Government on reforms to strengthen and harmonise whistle-blower protections

in the corporate sector with those in the public sector (informed by

consultation). |

July 2017 |

| Finalise and introduce

legislation for tax whistle-blower protections. |

December 2017 |

| Introduce legislation to

establish greater protections for whistle-blowers in the corporate sector,

with a parliamentary vote no later than 30 June 2018. |

By 30 June 2018 |

Source: Australian

Government, Australia's First Open Government National Action Plan 2016–18,

December 2016, p. 16.

International developments

2.44

This section sets out some of the international developments in

whistleblower protection legislation as part of greater global moves to tackle

corruption.

2.45

The international legal framework has been strengthened to combat

corruption and establish effective whistleblower protection laws as part of an

effective anti-corruption framework. Whistleblower protection requirements have been

introduced in the following ways:

- the United Nations Convention against Corruption;

- the 2009 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Recommendation of the Council for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public

Officials in International Business Transactions (Anti-Bribery Recommendation);

- the 1998 OECD Recommendation on Improving Ethical Conduct in

Public Service;

- the Council of Europe Civil and Criminal Law Conventions on

Corruption;

- the Inter-American Convention against Corruption; and

- the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating

Corruption.[46]

2.46

In 2010, the G20[47]

established an Anti-Corruption Working Group in recognition of the significant

negative impact of corruption on economic growth, trade, and development. In

November 2011, the G20 agreed to support the compendium of best practices and

guiding principles for whistleblower protection legislation (G20 Compendium),

prepared by the OECD.[48]

2.47

The G20 Compendium underscored the critical importance of promoting and

protecting whistleblowers in order to deter, detect and combat fraud and

corruption:

Encouraging and facilitating whistleblowing, in particular by

providing effective legal protection and clear guidance on reporting

procedures, can also help authorities monitor compliance and detect violations

of anti-corruption laws. Providing effective protection for whistleblowers

supports an open organisational culture where employees are not only aware of

how to report but also have confidence in the reporting procedures. It also

helps businesses prevent and detect bribery in commercial transactions. The

protection of both public and private sector whistleblowers from retaliation

for reporting in good faith suspected acts of corruption and other wrongdoing

is therefore integral to efforts to combat corruption, promote public sector

integrity and accountability, and support a clean business environment.[49]

2.48

The G20 Compendium identified the following specific features of

whistleblower protection mechanisms:

- definitions and scope:

- whistleblowing definition;

- good faith and reasonable grounds requirements;

- scope of coverage of persons afforded protection; and

- scope of subject matter or protected disclosures;

- mechanisms for protection:

- protection against retaliation;

- criminal and civil liability;

- anonymity and confidentiality; and

- burden of proof lowering in relation to retaliation;

- reporting procedures and mechanisms:

- channels for reporting;

- hotlines; and

- use of incentives to encourage reporting;

- enforcement mechanisms:

- oversight of enforcement authorities;

- availability of judicial review; and

- remedies and sanctions for retaliation; and

- awareness-raising and evaluation mechanisms.[50]

2.49

At the Brisbane G20 Leaders' Summit in November 2014, the G20 leaders

recognised the need to take concrete, practical action on corruption and

endorsed the 2015–16 G20 Anti-Corruption Implementation Plan. The plan

noted that:

The G20 has already recognised the significance of this issue

by adopting the G20 Guiding Principles for Legislation on the Protection of

Whistleblowers. The G20 now has the opportunity to build on this valuable

work and ensure all G20 countries implement comprehensive and effective

protections for whistleblowers in both the public and private sectors, ensuring

G20 countries lead by example.[51]

2.50

The specific deliverable agreed by the G20 in relation to whistleblowers

was:

G20 countries will conduct a self-assessment of their

whistleblowers protection frameworks in both the public and private sectors,

with reference to the OECD Study on G20 Whistleblower Protection Frameworks,

Compendium of Best Practices and Guiding Principles for Legislation, and

consider next steps.[52]

2.51

The 2017–18 G20 Anti-Corruption Action Plan continued its support

for whistleblower protections, noting that:

Encouraging the reporting of suspected actions of corruption

is critical to deterring and detecting it. We will promote this goal, including

reviewing our progress in implementing legislative and institutional

protections for whistle-blowers.[53]

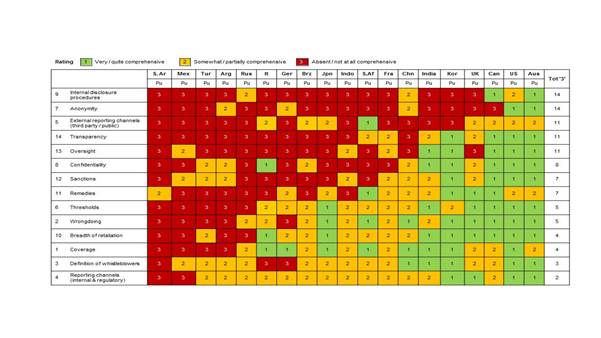

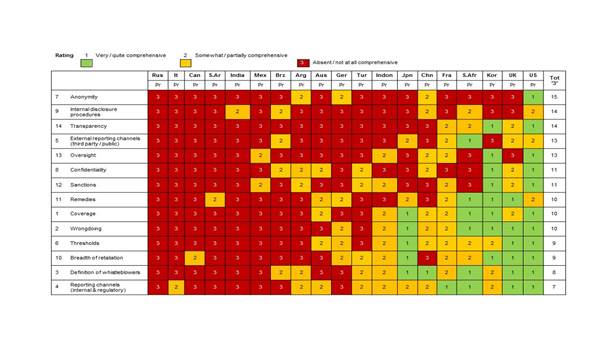

Analysis of international and Australia's whistleblower protections

2.52

The whistleblower protections in G20 countries were analysed in 2014

against principles for best practice set out in Table 2.2 below. Australia's

laws, were found to be comprehensive for the public sector, but lacking when

compared to international best practice for the private sector as shown in

Tables 2.3 and 2.4 below. The review suggested that in the private sector the

scope of wrongdoing covered is ill-defined, anonymous complaints are not

protected, there are no requirements for internal company procedures,

compensation rights are ill-defined, and there is no oversight agency

responsible for whistleblower protection.[54]

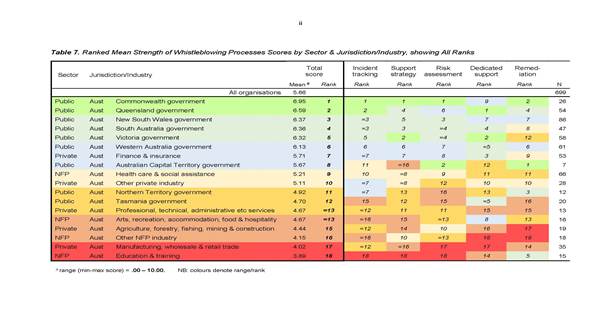

2.53

In May 2017, Professor Brown and his colleagues reported on their survey

on the strength of organisational whistleblowing processes and procedures in

Australia which was conducted as part of the Whistling While They Work 2 research

project. The survey's 699 respondents covered 10 public sector jurisdictions,

five private industry groups and four not-for-profit sector groups. The

analysis examined the self-reported presence of: incident reporting and tracking, support strategies

for staff, risk assessment processes for reprisals, dedicated support staff and

remediation processes.[55]

2.54

The results which are summarised in Table 2.4 show that even when trying

hard to encourage their staff to report integrity challenges, there is much

that organisations can do to ensure whistleblowing processes are robust. The

report also noted the following:

In particular, under the current state of guidance and

incentives, most sectors are finding it difficult to realise their own goals of

having processes which provide strong staff support and protection.

The results highlight that efforts towards strong processes

for ensuring support and protection can and should be enhanced, across all

sectors and in individual sectors.

Importantly, while size of organisation is a significant

factor in the strength of processes, sectoral differences remain irrespective

of size. This indicates that regulatory environment, oversight, operating

conditions, professionalization, skills and industry leadership are also

critical factors.[56]

Table 2.2: Summary of best practice criteria for

whistleblowing legislation.

|

Criterion |

Description |

| 1 |

Broad coverage

of organisations |

Comprehensive

coverage of organisations in the sector (e.g. few or no'carve-outs') |

| 2 |

Broad definition of reportable

wrongdoing |

Broad

definition of reportable wrongdoing that harms or threatens the public

interest (e.g. including corruption, financial misconduct and other legal,

regulatory and ethical breaches) |

| 3 |

Broad definition of whistleblowers |

Broad

definition of '[whistleblowers' whose disclosures are protected (e.g.

including employees, contractors, volunteers and other insiders) |

| 4 |

Range of internal / regulatory

reporting channels |

Full range

of internal (i.e.

organisational) and regulatory agency reporting channels |

| 5 |

External

reporting channels (third party / public) |

Protection

extends to same disclosures made publicly or to third parties (external

disclosures e.g. to media, NGOs, labour unions, members of Parliament) if

justified or necessitated by the circumstances |

| 6 |

Thresholds for

protection |

Workable thresholds for protection (e.g.

honest and reasonable belief of wrongdoing, including

protection for 'honest mistakes'; and no

protection for knowingly false disclosures or information) |

| 7 |

Provision and

protections for anonymous reporting |

Protections

extend to disclosures made anonymously by ensuring that a discloser (a) has

the opportunity to report anonymously and (b) is protected if later

identified |

| 8 |

Confidentiality protected |

Protections

include requirements for confidentiality of disclosures |

| 9 |

Internal disclosure procedures

required |

Comprehensive

requirements for organisations to have internal disclosure procedures (e.g.

including requirements to establish reporting channels, to have internal

investigation procedures, and to have procedures for supporting and

protecting internal whistleblowers from point of disclosure) |

| 10 |

Broad protections against retaliation |

Protections

apply to a wide range of retaliatory actions and detrimental outcomes (e.g.

relief from legal liability, protection from prosecution, direct reprisals,

adverse employment action, harassment) |

| 11 |

Comprehensive remedies for retaliation |

Comprehensive

and accessible civil and/or employment remedies for whistleblowers who suffer

detrimental action (e.g. compensation rights, injunctive relief; with

realistic burden on employers or other reprisors to demonstrate detrimental

action was not related to disclosure) |

| 12 |

Sanctions for retaliators |

Reasonable

criminal, and/or disciplinary sanctions against those responsible for

retaliation |

| 13 |

Oversight authority |

Oversight by

an independent whistleblower investigation / complaints authority or tribunal |

| 14 |

Transparent use of legislation |

Requirements for transparency and

accountability on use of the legislation (e.g. annual public

reporting, and provisions that override confidentiality clauses in

employer-employee settlements) |

Source: Wolfe, Worth, Dreyfus,

and Brown, Breaking the Silence: Strengths and Weaknesses in G20

whistleblower protection laws, October 2015, p. 6.

Tables 2.3 Strengths and

weaknesses in G20 country public sector whistleblower protections laws

Source: Simon Wolfe, Mark Worth,

Suelette Dreyfus, and A J Brown, Whistleblower Protection Laws in G20

Countries: Priorities for Action, September 2014, p. 6.

Table 2.4 Strengths and

weaknesses in G20 private sector whistleblower protections laws

Source: Simon Wolfe, Mark Worth,

Suelette Dreyfus, and A J Brown, Whistleblower Protection Laws in G20

Countries: Priorities for Action, September 2014, p. 7.

Table 2.5: Strength of

whistleblowing processes by sector & jurisdiction / industry

Source: A J Brown and Sandra A

Lawrence, Strength of Organisational Whistleblowing processes – analysis

from Australia, May 2017, p. ii.

2.55

The results of the survey analysis indicate:

- significant efforts by public and private sector organisations to

improve whistleblower protections;

- the higher relative strength of whistleblower processes in the

public sector compared to the private sector;

- that larger organisations appear to have stronger processes;

- that the finance and insurance industry group appear to have

stronger processes than some other sectors;

- the comparative weakness of local government processes, relative

to central government, in all jurisdictions other than Victoria; and

- the need for clearer guidance, and either statutory or industry

requirements, or incentives, across key areas of whistleblowing processes

especially for the private and not-for-profit sectors.[57]

2.56

The authors note that the stronger public sector results (compared to

the private sector) are consistent with stronger legislation over a period of

time and the international history of more comprehensive research into public

sector whistleblowing processes over private sector ones.[58]

However the results also show significant variations between public sector

jurisdictions which raise questions about the difference in those frameworks

and their implementation.[59]

2.57

The report also concluded that legislative reforms such as the

implementation of the PID Act, led to a significant improvement in the

Commonwealth whistleblowing processes, which are now among the strongest in

Australia. The report notes for example that:

Commonwealth agency heads came under a direct statutory

responsibility to take 'reasonable steps... to protect public officials who

belong to the agency from detriment, or threats of detriment' relating to

disclosures.

...the two jurisdictions who scored most strongly for risk

assessment – the Commonwealth and ACT – are the only jurisdictions

where, by statute, agencies are required to have processes for assessing risks

that reprisals may be taken against the persons who make those disclosures.[60]

2.58

The following chapters focus on the evidence the committee has received

arguing for and against a range of potential reforms to whistleblower

protections.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page