Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Chapter 10 - Rural transaction centres

10.1

The giroPost experience demonstrates the enormous advantages to be

gained through co-operation between financial institutions and other

enterprises. Such collaboration coupled with advances in technology broaden the

scope for improved delivery of financial services to country Australia.

10.2

This chapter looks at another venture, the Rural Transaction Centre

(RTC) Program, that is presenting similar opportunities for various parties to

enter a joint arrangement to provide a range of services including banking and

financial services to small country towns. The first section of this chapter

documents the history of the CreditCare initiative—the predecessor to the RTC

program—before examining in detail the operation of RTCs.

CreditCare

10.3

Credit unions and the Commonwealth initiated the CreditCare project in

June 1995 with the aim of using the self-help and community focus of credit

unions to meet the challenge of providing financial services in ‘no bank’

towns.[1]

10.4 Within two years of its establishment, the program had contacted 85

communities around Australia and facilitated the development of 29 new

establishments.[2]

In light of its success, the project received in 1997 an additional $2.4

million to extend its operation for a further three years.[3] Almost 60 communities—serving around 40,000 residents—regained access to

financial services through initiatives under the CreditCare program[4]

(see appendix 6).

10.5

The funding established a network of CreditCare Field Officers, employed

through CUSCAL and with experience in the provision of financial services, to

work with communities to bring financial services back to their town. Community

groups such as the Crows Nest Tourist and Progress Association appreciated the

early assistance offered through the CreditCare program. According to members

of the association, CreditCare provided the necessary outside expertise, the

confidence building, the structure and finally the support to push their

venture of a community bank ‘over the line’.[5]

10.6 It should be emphasised that CreditCare did not cover the start-up costs

or provide the initial seed funding for institutions to open services in

smaller communities in regional Australia. Rather the program relied on

community support to develop a detailed business plan to demonstrate the

viability of the service provision to a financial institution.[6]

Dr Gary Lewis explained:

The model was carefully designed to neither directly fund nor

subsidise the establishment of credit union branches or agencies. Rather the

program provided resources to assist communities themselves discover the

means of re-establishing financial services utilising existing resources, and

link these with a host institution. CreditCare’s maxim was that it was in a

community not simply to help but to help a community help itself.[7]

10.7

CUSCAL believed that the lack of funds in this area was a real

constraint on the capacity of the program and that it reached a point where

there ‘seemed to be limited opportunities for the sector—largely, the credit

union sector—to continue to open those services without some additional support

for some of the infrastructure and start-up costs’.[8]

10.8

While the CreditCare scheme was a valuable model that offered important

lessons for policy makers, it became apparent that ‘a wider program was

required to address growing service needs in towns without banks.’ Since the

closure of the CreditCare program in 2000, federal initiatives to deliver

financial services to rural areas have been implemented through the Rural Transaction

Centre scheme. As with the CreditCare program, the RTC programs focus on small

towns without banks.[9]

Background to the RTC programme

10.9

The RTC scheme was launched in March 1999, as a Commonwealth Government

initiative to restore services to rural and regional Australia. It is a $70

million program over five years and was funded from the sale of the first

tranche of Telstra to establish 500 RTCs in rural areas with populations of up

to 3,000.

10.10

The Program was designed as a grassroots measure to provide funds to

help small communities with practical and focused support.[10]

It is based on the premise that in some instances the provision of a particular

service such as a banking or welfare service may simply not be feasible as a

stand-alone operation but may be viable in conjunction with the provision of a

number of other services. In essence, the RTC model is based on the core

assumptions that:

- there are extensive economic and community benefits to be gained

from the collocation of government, private sector and community services; and

- in the longer term, the centres will develop into sustainable

community managed small businesses.[11]

10.11

The RTC scheme involves considerably more funding than the CreditCare

project, including options to subsidise infrastructure and operational costs.

As noted above, the limitation in being able to assist with start-up costs was

a significant weakness in CreditCare projects. CUSCAL was of the view that the

RTC program appeared to offer a much ‘better funded model that would enable some

of those issues to be addressed’. It should be noted that, after initial

funding for start-up costs or running costs during an establishment period,

RTCs are expected to be self sustaining.[12]

10.12

Each RTC is tailored to meet the varied and unique needs of the

community it serves. The types of services they offer include:

- financial services (including business services)

- post, phone, fax, Internet

- medicare easyclaim

- Centrelink

- facilities for visiting professionals

- printing, secretarial services

- tourism, involvement in employment schemes

- insurance, taxation

- federal, state and local government services.

In 1999, Senator the Hon. Ian MacDonald, then Minister for

Regional Services, Territories and Local Government, explained:

The local communities decide the range of services, the service

providers, the location of the centre and manage its operation. We just provide

the set up funds.[13]

10.13

Before plans can proceed in earnest, those applying for funds must

establish a case showing that their proposal is commercially viable. The

Department of Transport and Regional Services described the process in applying

for RTC funds:

Generally RTC applicants are required to demonstrate that

any RTC will be viable and sustainable in the longer term either through the

anticipated business turnover or indirectly through the commitment of a third

party such as a local government.[14]

10.14

It informed the Committee that in some instances the RTC Program has

contributed to the costs associated with providing a building to house the

financial services or assisted with the costs of equipment such as ATMs and

safes. It noted that generally the financial institution funds the installation

and running costs of terminals and other significant equipment.[15]

The RTC program and Post Office outlets

10.15

As part of the RTC Program, the Commonwealth Government is funding

eligible Licensed Post Offices to install Australia Post’s electronic point of

sale (EPOS) equipment. It allows access to giroPost.

10.16

As noted in the previous chapter, there are approximately 900 Australia

Post outlets nationwide that do not have the electronic equipment to deliver

on-line financial transactions. According to both Australia Post and the Post

Office Agents’ Association, 12,000 transactions of a financial nature are

required before the installation and use of giroPost is commercially viable.

The RTC Program provides two avenues for non on-line outlets in rural and

remote areas to apply for funding for the provision of giroPost:

- under the business planning process a community group may request

funding for a range of functions including giroPost to be located at the local

postal outlet; and

- a separate phased process allows the Licensee to apply directly

for giroPost funding from the RTC Program.[16]

10.17

Under the Program, the installation of EPOS is being implemented in

stages:

- phase 1—Licensed Post Offices processing over 5,000 transactions

at 30 June 2001;

- phase 2—Licensed Post Offices processing over 5,000 transactions

with limited financial services.[17]

10.18

It should be noted that Australia Post informed the Committee that of

their 900 outlets without giroPost only 21 per cent or 193 record between 5,000

and 10,000 transactions a year and 40 per cent conduct between 2,500 and 5,000.

10.19

In effect, the scheme would see the RTC program fund the provision of

giroPost in circumstances where the Post Office outlet falls below the required

12,000 transactions. As at March 2003, one hundred and four had been brought

on-line over the previous 18 months or so and a further 60 had been invited to

apply through the RTC program. Mr McCloskey, Australia Post, explained:

The capital funding has been provided from the RTC program.

In the initial stages, any shortfall in the operating costs are being met under

the RTC program. Once that program finishes, part of the condition is that the

licensees will then become liable—if that is the correct word—to pay an annual

technology fee to Australia Post, which is something that licensees currently

do under the EPOS system, and Australia Post will look at picking up the shortfall

if the number of transactions in those particular outlets does not reach the

10,000 limit.[18]

10.20

The Post Office Agents Association welcomed the extension of the RTC

program to some of their manually operated outlets but could see advantages in

extending EPOS to all post offices which it suggested ‘would be a huge boost to

country areas.’ It noted correctly, however, that some post offices may be so

small that even with technology they are never going to be viable giroPost

facilities.[19]

RTCs—broad support

10.21

Partnership between various groups—private enterprise, community groups

and government—are central to the success of the RTC program. The CPS Credit

Union (SA) Ltd stated that communities must be prepared to co-contribute to the

banking services within their community. Similarly it argued that governments

(State and Local) will need to co-operate more with the communities and

financial institutions to provide some of the infrastructure needed.[20]

Support from local government

10.22

Many local councils recorded their approval of the RTC model recognising

its potential for expanding services in smaller country locations.[21]

Mr Goodfellow, Elders Rural Bank, stated that one of the better options for

delivering financial services in small towns was through the shire or local

council. He maintained:

The rural transaction centre concept—with a lot of negotiation

and discussion amongst local government associations and members and, more

recently, at a higher level of government—has provided opportunities and cash

flow for rural transaction centres to prosper.[22]

10.23

Mr Nigel Hand from the Port Broughton RTC agreed with the view that the

local council can have a pivotal role in both establishing the Centre and

ensuring its viability by offering assistance such as providing premises at

less than cost, access to equipment and help with staffing.[23]

In Blackbutt, the RTC runs at a loss of approximately $8,000 per annum but

continues to operate through the direct assistance of the Nanango Shire

Council.[24]

Indeed, in numerous cases the involvement of local government in supporting

RTCs has been essential.[25]

10.24

The Gulin Gulin & Weemol Community Council Aboriginal Corporation

submitted that for several months it had been working towards the development

of a business plan for the operation of an RTC in Bulman. It saw the RTC

program as an ideal solution—‘a proven means to provide additional services’.[26]

10.25

The Narrandera Shire Council also recognised the advantages in having

RTCs provide small communities with access to electronic banking services. An

RTC was opened on 27 August 2003 at Barrellan due to the joint efforts of the

Council and the owner of the Australia Post outlet through the Department of

Transport and Regional services. It offers e-banking facilities using giroPost,

Centrelink Access Point, Medicare easyclaim, public access to business

equipment and to Internet and e-mail facilities.[27]

The Council urges the Government to continue with this program.[28]

Endorsing this view, the Summerland Credit Union Limited submitted that:

The continued establishment of RTCs is to be applauded and

will no doubt provide a valuable service to a good many rural and remote

communities. This is especially so for those communities deemed too small to

support any sort of commercial enterprise be it bank or credit union. Not only

do RTCs meet their banking needs but also assist in providing some of the

services they have traditionally lacked or replacing those that have

disappeared following the latest round of withdrawal of many government

services.[29]

10.26

It envisaged the expansion of RTCs not only as filling a gap in the

provision of banking services to rural and regional communities but as a means

to reverse the trend of declining services. It stated:

The maintenance and expansion of the RTC scheme will have a

number of positive flow on effects. Not only will it provide essential banking

services to a large part of regional Australia from which the banks have

withdrawn services but it will also assist in creating a significant number of

employment prospects within that area.[30]

10.27

Likewise, the Nanango Shire Council welcomed the establishment of an RTC

in Blackbutt which provides many government services and has become ‘a true

advantage’ for its residents. According to the Council, the RTC is instrumental

in cutting travelling time and expense for residents who do not have to journey

to a larger regional town to avail themselves of these services.[31]

Support from financial providers

10.28

There are many financial service providers keen to participate in the

program. The Summerland Credit Union Limited, told the Committee that credit

unions in particular have a social charter to provide cooperative banking

services to those overlooked by the traditional banking services. It maintained

that participation in the RTC program ‘sits very comfortably with this charter

and is an area in which the credit union industry has considerable expertise’.

It saw a role for credit unions in facilitating the roll out of such a program.[32]

10.29 A number of the major banks have also shown an interest in the program.

The ANZ is actively involved in the RTC initiative through providing full

personal and business banking transaction services at the Victorian Rural

Transaction Centre in Welshpool and the South Australia RTCs in Port Broughton

and Port Macdonnell.[33]

It noted:

The RTC program is a viable alternative because the third party

who operates the RTC, such as the local council, community organisation or

chamber of commerce, provides the infrastructure and staffing costs. This

provides an opportunity for ANZ to provide face-to-face banking services on a

lower cost basis than would otherwise be possible.[34]

It supported this initiative which in its view has

been successful in increasing the level of face-to-face banking in a number of

rural and regional locations.[35]

10.30 Westpac is also involved in the program. It informed the Committee that

the local community in Leitchville, Victoria, approached it to purchase its

former bank premises. Westpac explained that:

The community only had $10,000 to invest so Westpac subsequently

agreed to make the sale for that amount. The community has subsequently

established a Rural Transaction Centre which includes a Westpac In-store.[36]

Shortcomings of RTCs

10.31

Although many witnesses supported the RTC program, some nonetheless

criticised or raised questions about the followings aspects:

- the implementation process;

- the limited range of services;

- commercial viability;

- maintaining momentum; and

- future funding.

The following section looks in turn at the issues

identified above.

Implementation—slow start

10.32

A number of witnesses were disappointed with the program’s slow start.

The Finance Sector Union of Australia observed that there were 49 RTCs

throughout Australia which is ‘hardly an adequate replacement for the thousands

of branches closed across the country’.[37]

The Summerland Credit Union, which has been involved in one such establishment

at Coraki, also noted that only 49 RTCs had been established with a smaller

number still in the pipeline.[38]

A recent update shows that to October 2002, 124 RTCs had received approval and

there were 65 communities which had operational RTCs.[39]

This number is still far short of the goal of 500 RTCs. Further, nearly one

third of these establishments were initiated under the CreditCare scheme.

10.33

According to Mr Shaun McBride, Local Government Association of New South

Wales, the program’s goals had probably been optimistic but the program was

gathering some momentum.[40]

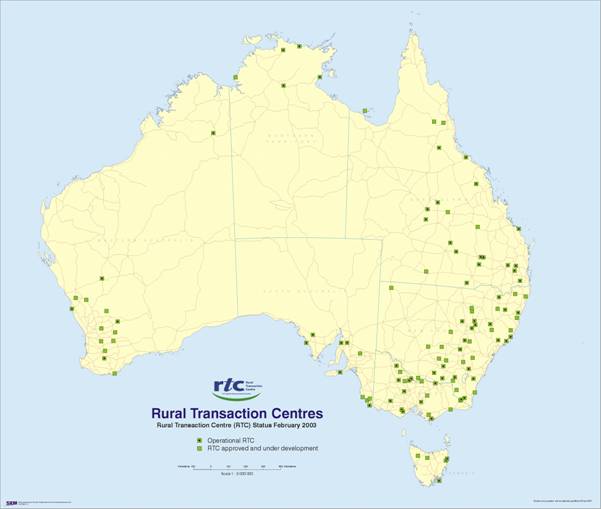

Figure 10.1—Status of Rural Transaction

Centres, February 2003

10.34

In drawing attention to the time taken to establish an RTC, the

Summerland Credit Union cited a number of reasons for the slow start ranging

from ‘the difficulties in galvanising local support, through to overcoming the

bureaucratic obstacles associated with any government funded scheme’.[41]

It suggested that the program administration be streamlined to speed up the

process of establishing an RTC. In its view, this process could involve ‘the

elimination of a number of layers of government involvement with say funding

provided direct to local government’.[42]

10.35

CUSCAL also identified problems with delays in the establishment of new

RTCs and the lengthy approval processes as major concerns. It claimed that

‘limited support for the community building phase of compiling applications and

business plans’, placed a high demand on volunteer community members.[43]

It also recommended a streamlining of approval and review processes for

communities to reduce waiting times.[44]

10.36

Based on its experiences with establishing RTCs at Dirrandbi and Bell,

the Heritage Building Society found the process ‘fairly cumbersome and time

consuming.’ It also noted the difficulties during the start-up period of an RTC

and recognised the need for funding for the initial inquiry and survey costs to

establish the business case for such a facility.[45]

Mr Read-Smith acknowledged that the early exploration stage could be a big

impost on a community to raise funds for the surveys to establish the

commercial viability of a proposal. He added ‘particularly as it is moneys that

is, in a sense, at risk, it may not lead, depending upon outcome of the

business case analysis, to a project getting off the ground’. He suggested that

this is an area where governments could play a role.[46]

10.37 The Committee appreciates the importance of early and well-targeted

assistance from the Department of Transport and Regional Services to guide

interested parties through the process of developing a business plan. It notes

the valuable role taken by field officers under the CreditCare scheme in

facilitating and expediting the early stages of investigating and planning for

the establishment of a community-based service provider.

Limited range of services

10.38

While appreciating the contribution that RTCs are making in providing

financial services, CUSCAL was concerned that a number of RTCs appear to offer

very limited services and some are operating without a financial service

component. It considered the provision of a financial service in an RTC as

essential to its viability.[47]

It claimed:

RTCs are ‘output’ focused, often with limited services (eg

Medicare Easyclaim). While important, these services alone do not deliver on

the program aims.[48]

10.39

The Department of Transport and Regional Services informed the Committee

that of the 65 communities that have operational RTCs only 26 deliver a

financial service through either a bank, credit union, building society or

community bank.[49]

10.40 CUSCAL also maintained that the RTC model had not expanded to seek new

service areas or partnerships with private and public sector bodies. It suggested

that the program has limited focus that is tied to creating a viable commercial

model to sponsor additional services.[50]

10.41

The Committee accepts that progress in implementing the program is

disappointing and is particularly concerned that so few RTCs offer a financial

service.

Meeting the needs of business

10.42

RTCs share the same problems as agencies and post office outlets in

catering for the particular needs of small business (see paragraphs 9.19–9.22).

They do not always meet or suit the requirements of business customers and face

security and privacy issues. For example, most RTCs do not facilitate business

transactions including business cash deposits and withdrawals nor form part of

the commercial world providing advice and access to finance so necessary for

small businesses to develop. The Gunning Shire Council informed the Committee

that it was successful in establishing an RTC within the Gunning Post Office.

It noted, however, that only $3,000 can be banked in any one day and third

party cheques cannot be banked into individual accounts.[51]

The Australian Centre for Co-operative Research and Development stated:

The capacity of locally owned businesses and social enterprises

can be enabled by locally based and supported financial institutions that understand

and help their business customers (eg develop business plans or look at

alternative sources of finance to expand and invest and overcome collateral

difficulties, and business cash flow difficulties). Recent years have seen a

huge decline in rural banking services that have not been replaced by services

that understand or cater for the financial needs of rural businesses and

community enterprises. Community banks, Rural Transaction Centres and Giro Post

institutions do not cater for the specific needs of small business and

community enterprise needs; nor do they attempt to understand what they are.[52]

10.43

The Report in Chapter 3 described at length how the absence of a bank

branch in a town creates difficulties for local businesses in the day-to-day

management of cash flow but also limits their access to professional advice and

to finance.[53]

Strategies to expand services

10.44

Of the RTCs that are established, the Department of Transport and

Regional Services highlighted the importance of commitment to the program. It

noted that community-driven solutions often rely on communities developing the

necessary skills to deliver and manage financial services. It asserted that

providing appropriate training and small business management skills to deliver

effective banking services can be time consuming and involves a continuing

commitment on the part of the community.

10.45 CUSCAL also noted the importance of sustaining the level of enthusiasm

for and commitment to the centres. It suggested, however, that there was a lack

of ongoing support services for RTCs once established.[54]

Indeed, during its site visit to Blackbutt, the Committee was surprised to

learn that no communication links had developed between the various RTCs, even

with those operating in neighbouring districts. It would appear that no one has

assumed responsibility for ensuring that operators and groups involved in the

work of RTCs form a nationwide network of enterprises pursuing similar goals.

At the moment there is no effective mechanism that brings RTCs together as a

cohesive group.

10.46

A number of councils raised a related issue dealing with the level of

communication and understanding that exists between the bureaucracy and those

seeking assistance from the program. They indicated that departmental officers

do not appreciate the uniqueness of communities, their specific needs and how

the RTC program could assist them. Mr Clinton Weber, Rosalie Shire Council,

told the Committee of difficulties the officers in Canberra had in

comprehending the decentralised nature of the shire with its numerous small

local towns with populations of between 200 and 300 people dotted throughout

the district. He stated:

Our main problem was getting somebody to understand where we

were coming from rather than them trying to explain to us where the program was

coming from.[55]

10.47

The Nyirranggulung Mardrulk Ngadberre Regional Council reported that

progress to establish an RTC at Bulman in the Northern Territory had stalled

because:

Bulman’s remoteness makes it impossible to undertake the negotiation

necessary to develop the agreements and commitments required to complete a

business plan...

The negotiation process was intended to be aided by an RTC Field

Officer. Whilst it may be true that our field officer was involved in

negotiation with providers at the general level of convincing providers of the

need to fully cost remote service provision, including lease of facilities, it

seems that specific negotiations to get agreements on the Bulman site never

took place.[56]

10.48

The Committee believes that the program could benefit greatly by having

a strong communication network linking all RTCs. This would give those involved

in the program a better appreciation of how RTCs operate in different areas,

the types of arrangements others have entered into and the range of services

they offer. For example the department was concerned about the disclosure of

commissions and their disparity between individual centres especially in light

of the lack of competition. It noted in its submission:

When entering into contractual arrangements with financial

institutions communities should be aware of the typical arrangements in place

in other communities. In terms of financial service providers in RTCs there is

great variation in policies on commissions and retainers and the products

offered differ. This has resulted in some disparity between RTCs. For example

commissions can range between $1.00 and $1.60 per transaction.[57]

10.49

In the Committee’s view, the RTC program should incorporate as part of

its on-going support and development strategies a component dedicated to

bringing RTCs together to share and gain valuable insight from each other’s

experience. Regular workshops would provide an ideal opportunity for those

involved in RTCs to exchange ideas. The Committee envisages the Department of

Transport and Regional Services as a catalyst in facilitating communication

between RTCs. Through this type of involvement, the department would not only

foster stronger links between RTCs but would enable its officers to gain a

better understanding of the operation of RTCs in other areas and the various

approaches taken to expand the businesses. With the assistance of those

actually working in the RTCs, the department would be better placed to develop

and implement measures to improve the operation of the scheme and to offer

guidance to those contemplating establishing an RTC.

Recommendation 9

The Committee recognises a need for those managing RTCs to be part

of a more effective communication network so that they can benefit from each

other’s experience and provide valuable advice for those considering applying

for assistance. The Committee recommends that the Department of Transport and

Regional Services take a more active role in encouraging the development of

stronger links between RTCs throughout Australia and between RTCs and

departmental officers.

10.50

In looking at matters such as the Government’s role in assisting

communities with the establishment of an RTC, the question arises about

on-going support for the program. Some witnesses argued that the Government

should remain an active partner in the RTC program and that its involvement

should go beyond merely the establishment of an RTC. CUSCAL stated:

...whilst many of those RTCs are operating very effectively, there

continues to be a need for a government program that oversees and coordinates

some of those initiatives and assists those centres. It would be a tragedy if

those communities that had fought to get services back to their area lost out

because of the lack of a coherent strategy or a strategy that continues to be

funded post mid-2004.[58]

10.51

The Committee is concerned about ensuring that the program not only

retains momentum but explores new ways to expand and improve its operation.

This matter raises the issue of funding the program not only to make certain

that the gains already made are not lost but to determine whether extra funding

is warranted.

Funding

10.52

The same economic imperative applies to RTCs as to giroPost and

community banks—they need to achieve a level of activity to ensure that the facility

becomes commercially viable. Put bluntly, however, there are some localities

that are not able to support an RTC. Mr McBride, Local Government Association

of New South Wales concluded:

I think in some areas it was never realistic to expect them to be

self-funding—maybe contributing significantly to their cost, but never fully

self-funding.[59]

10.53

For example the Laverton Shire Council investigated the setting up of an

RTC. It received a grant under the program to carry out a feasibility study but

failed to establish that the enterprise would be commercially viable. The RTC

service, therefore, has not proceeded because the proposed centre would not

have been self-sufficient in the long term.[60]

10.54

The situation in very small communities, where the local economy cannot

support even a basic banking facility, presents challenges for decision makers

and questions the requirement for all RTCs to be self-funding. Indeed, some

submissions saw increased funding as a means to further support the RTC program

and advocated a less demanding approach to the requirement for a centre to be

commercially viable.[61]

10.55

The Summerland Credit Union would like to see ‘a further financial

commitment to fund the establishment of a far greater number of Rural

Transaction Centres, as was initially intended’.[62]

The Rosalie Shire Council submitted that it may be necessary for the RTC

program to finance any losses involved in operating this service, at least for

a period up to five years, after which the level of assistance could be

reviewed.[63]

10.56

In some cases, the local council has been prepared to subsidise an RTC.

The Nanango Shire Council provides between $8,000 and $10,000 to the RTC at

Blackbutt to keep it operational. When the National closed its doors in

Blackbutt five years ago, it left the town of 800 people and a district of

2,000 without banking services. Councillor Lee explained:

...if we were to wave a wand tomorrow and the credit union in

Blackbutt disappeared, there would be a terrific upheaval over it. You could

not do it, because it is a community facility that is provided by the council

and is expected by those people down there to be provided by local authority.[64]

10.57

In this case the local council has accepted responsibility for ensuring

that the residents of Blackbutt have a banking service in their town. This

situation poses the question about whether such an undertaking is the

responsibility of local government. Mrs Zerbst felt that the council has a lot

of other services to deliver and should not be the ones that have to provide

financial services to a town.[65]

10.58

The Committee accepts that some areas may not qualify for assistance

because they cannot establish a sound business case for an RTC. Clearly some

councils, recognising this commercial reality, propose that funding under the

RTC program should be extended beyond the current guidelines. This issue of

funding raises the question about subsidisation for communities unable to

qualify for RTC funding on commercial grounds alone. The same issue arose in

relation to the absence of giroPost in towns where the number of financial

transactions simply could not support its installation.

10.59

Professor Ian Harper stated that he thought it was acceptable for

government to support or subsidise programs such as RTCs but with

qualifications. He told the Committee:

...it is entirely appropriate for the Australian government to

be easing the community through this transition...my concern is that the

motivation behind it is not to stop the advance of a tide which is simply

unstoppable. By all means, provide tax breaks to regional areas and subsidies

that are targeted. Provided they are competitive, they can seed this process.

Sometimes all that is necessary is to publicise the opportunities.[66]

10.60

The Committee acknowledges the work that has been achieved through the RTC

program and recognises that it has the potential to continue to make a valuable

contribution to the provision of services to regional, rural and remote Australia.

It fully supports on-going funding for the RTC program. Even so, the Committee

believes that the program could benefit from a review of its operation.

Conclusion

10.61

The Committee endorses the RTC program as an effective means of

restoring services to towns. It also notes that an RTC is a means of providing

services to a small community that may never have had such services.

10.62

The Committee witnessed the success of the RTC program when it looked at

the contribution being made by the Electricity Credit Union and the Heritage

Building Society in delivering banking services to small communities in South

West Queensland. In both cases, the institutions had stepped in to fill the

void left by the major banks which had either left the community without a bank

presence or were withdrawing their services from the town. In both cases the

community organisation had assistance from either the CreditCare or RTC

program. The RTC at Port Broughton with assistance from the local council was

also delivering banking services to a community in need of improved banking

services.

10.63

An RTC can be a means of renewing confidence, promoting local

enterprise, and providing a convenient and safe location for people to conduct

their banking affairs with staff on hand to assist them in transacting

business. This in turn may reverse the trend of declining services by

attracting and retaining business in the town. The presence of an RTC, however,

does not address all the problems experienced by a community that has lost or

never had access to adequate basic services.

10.64

While the Committee believes that such a scheme holds promise it is

concerned about:

- its slow progress;

- the number of RTCs that do not provide banking and financial

services;

- sustaining, even reinvigorating, the program to ensure that the

progress made is built upon and not eroded;

- future funding.

10.65

In light of such concerns the Committee makes the following

recommendation:

Recommendation 10

The Committee recommends that the Australian Government conduct a

review of the RTC program and its future direction. The review would:

- identify ways to streamline the process of applying for

funding and to better assist communities formulate a business case for an RTC;

- develop a program designed to produce a better and more

effective communication network between individual RTCs;

- establish why many RTCs do not provide banking or financial

services;

- examine the scope and formulate a better strategy for

extending the services provided by the centres particularly the provision of

banking and financial services;

- determine the adequacy of the level of funding, especially the

requirement for on-going funding, to ensure that established centres maintain

their momentum and that new centres can be established; and

- consider the value in subsidising RTCs in localities without

accesses to banking services but which would have difficulty in becoming self

sufficient.

10.66

The drafting of this report was nearing completion when the Australian

National Audit Office released its performance audit report, The

Administration of Telecommunications Grants, which looked at a number of

government programs including the RTC program. Among its key findings was that

the Department of Transport and Regional Services did not translate the

Government’s program objectives for the RTC program into ‘operational

objectives that would have helped to establish an appropriate performance

management framework to monitor the efficiency and effectiveness of program

delivery’. It found failings in the initial planning process, in particular

‘the absence of any mechanism for feeding information gained from the

evaluation of individual projects into an evaluation of the efficiency and

effectiveness of the programs.’

10.67

The audit report noted that the department is aware of many of the

shortcomings with the administration of the RTC program and is working towards

resolving them.

10.68

Although the audit report and this report cover some common ground and

the department is taking action to evaluate and rectify a number of problems

highlighted in the auditor’s report, the Committee believes that it should

nonetheless retain its recommendation for the Government to review the program.

In doing so, the Committee wants to reinforce the message coming out of the

auditor’s report and the department’s own evaluation that a serious review is

needed and problems with the program must be addressed.

10.69

Furthermore, the Committee emphasises that any review of the program

should place a clear emphasis on RTCs as providers of banking and financial

services and be directed at enhancing this role not downgrading it

Recommendation 11

In light of the findings of the Auditor-General, Audit Report No.

12, 2003–4, The Administration of Telecommunications Grants, the Committee

recommends that the Government make a public recommitment to the RTC program

especially to enhancing its role as a provider of banking and financial

services to areas without access to such services.

10.70

Community banks, giroPost and the RTC program have demonstrated that

small communities together with private enterprise and government assistance

can work together to find solutions to providing their communities with access

to banking and financial services. As noted in the report such joint ventures

require the combination of a number of key factors—community drive, commitment

and leadership, critical mass, a sympathetic and willing financial service provider

and in some instances government subsidy. Even when these factors do come

together, the provision of banking services may fall short of the community’s

needs and expectations.

10.71

Advances in technology offer some hope of improved banking and financial

services. The following section of the report focuses on this aspect of banking

services.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Top

|