Chapter 3

Impact of illicit firearms on the community

3.1

The impact of illicit firearms on the community through their use, in

particular in violent crime, is a key issue arising from the illicit firearms

market in Australia. The use of illicit firearms in the commission of offences

and the impact on the Australian community is considered in this chapter.

3.2

The Victims of Crime Assistance League highlighted that victims of

gun-related crime suffer enormously and often in a way largely un-acknowledged

by the wider community:

There is always a concentration in the media on those more

salacious incidents such as death and murder. Where we do not have a great

concentration, but still have a problem, is on robbery with a weapon. I have

dealt recently with a young woman who was a service station attendant where

some toerag came in with a sawn-off shotgun. Because there were time delays, he

decided that he needed to wait until that time delay was open so that he could

access the safe. So he placed the shotgun in her mouth, gaffer taped it to her

and said, 'Okay, darling, we will sit here until the safe opens.' The trauma

that that woman sustained in that assault was unbelievable. We spent hundreds

of hours counselling this poor woman and getting her back to a point where she

could live a seminormal life. But it was a robbery of a service station. It

made five lines in the local press and a small block in The Sydney Morning

Herald. No-one gave a damn about it—because she survived.[1]

3.3

Gun Control Australia (GCA) remarked that the total availability of

firearms in the community is directly related to gun violence:

GCA is of the view it is a reasonable conclusion that the

more guns there are in the hands of the community generally, the greater the

number of incidents of gun violence...The relationship between the prevalence of

guns in the hands of the community and gun violence was first identified by

Professor Richard Harding in his seminal work on firearms in Australia,

published in 1981. Professor Harding was for many years a director of the

Australian Institute of Criminology and one of Australia’s most respected

criminologists. To Professor Harding, firearm violence was, effectively, a

product of gun availability.[2]

3.4

Evidence from the Australian Crime Commission (ACC) indicated that these

risks to the community increase when firearms are unaccounted for:

The imperishable nature of firearms ensures that those

already available within the illicit market remain a serious threat...The

durability of firearms ensures that those diverted to the illicit market can

remain in circulation and are available for use by criminals for many decades.

The oldest firearm traced by the ACC was a functioning revolver manufactured in

1888.[3]

3.5

NSW Police acknowledged the threat posed to the community by stolen

firearms[4]

and discussed the large pool of unaccounted firearms in the community:

There is no doubt that there is a large number of firearms

out there. Whether those firearms then go into the black market is another

question altogether, and, as I said, it is only at the time that police recover

those firearms that we are able to establish their origin. We may not be able

to establish their origin if they are from the grey market, simply because

people do not report their theft for fear of facing some sort of criminal

sanction themselves.[5]

3.6

The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) discussed the low recovery

rate with respect to stolen firearms, with 12‑14 per cent of incidents

resulting in the firearm being recovered in a 12-18 month period after the

report of the theft.[6]

The low rate of recovery of stolen firearms only serves to maintain this pool

of unaccounted firearms available for illicit uses. The use of these illicit

firearms in gun-related and organised crime is explored in the following

sections.

Firearm-related crime

3.7

Illicit firearms are used in a range of serious and aggravated crimes,

such as homicide, armed robberies and sexual assault. Their use is therefore a

serious concern for the community and law enforcement authorities alike.

3.8

While statistics do not measure the huge personal impact gun-related

crime has on a victim, they do provide a useful means of assessing the impact

of illicit firearms on the community by measuring the types of crime committed

with a firearm and the frequency of these.

3.9

Data from the National Homicide Monitoring Program (NHMP) shows that the

majority of firearm homicides in Australia between 1989-90 and 2009-10 were

committed by an unlicensed offender (79-93 per cent of offenders), the majority

of offenders used a firearm that was not registered (83-97 per cent) and there

was a 15 per cent decrease in the number of firearm homicides over the 25

year period (76 in 1989-90 to 31 in 2009-10).[7]

3.10

This reduction in firearm-related homicides is juxtaposed with their use

in armed robberies which increased between 2005 and 2010. The AIC informed the

committee that sixteen per cent of armed robberies committed in Australia

between 2004 and 2010 involved a firearm, from a low of 13 per cent in 2005

(758 incidents) to a high of 18 per cent in 2010 (825 incidents).[8]

Data from the National Armed Robbery Monitoring Program (NARMP) found that in

2009-10, handguns were used in nine per cent (1162 incidents) of armed

robberies in Australia and shotguns were used in three per cent (340

incidents).[9]

3.11

The NARMP also provided data on the types of armed robberies that

predominantly involve the use of a firearm:

Firearms are used in the robbery of organisations more often

than in attacks against individual victims. In 2009–10, only eight percent of

individual victims robbed in the street were threatened with a firearm, while

around one-third of those victimised in banks (35%) and in licensed premises

(33%) were subject to firearm robbery (Borzycki & Fuller 2014).

An examination of 627 armed robbery narratives collated as

part of the NARMP showed an association between the targeting of secure

businesses, planning and the use of a firearm (as opposed to another weapon;

see Fuller forthcoming). Additional data from the NARMP also demonstrates that

firearms were more likely to be used in high-yield armed robberies between 2004

and 2010 (ie where the property stolen was greater than $10,000; see, for

example, Smith & Louis 2010) and when secure businesses were targeted (Borzycki

& Fuller 2014). For example, organisations with substantial cash holdings

and therefore with more security, such as banks and licensed premises, were

robbed by offenders armed with firearms at much higher rates (68% and 44%

respectively) compared with robberies at less secure sites (15%).[10]

3.12

The NSW Justice Cluster found that the use of handguns is particularly

prevalent in public place shootings in NSW: 90 per cent of such shootings

involve handguns.[11]

Similarly, NSW Police advised that:

...semiautomatic handguns are the weapon of choice, for people

on the streets of Sydney particularly. There is no doubt about that. Our

ballistics people have instructed me that at this stage, 90 per cent of gun

crime generally in New South Wales can be attributed to semiautomatic handguns;

absolutely...Not every crime scene results in a trace to a particular firearm. It

can come up to a particular type of firearm, but it may not specify the exact

weapon used...In terms of it being a registered firearm, I do not have the exact figures

but it appears to be not a lot; the majority is as a result of illegally

obtained, semiautomatic handguns.[12]

3.13

In response to questions taken on notice, NSW Police told the committee

that 16.2 per cent of assaults, 44.2 per cent of robberies and 33.3 per cent of

sexual offences involving the use of a weapon in 2014 (up to 29 November)

involved the use of a firearm.[13]

3.14

Western Australia Police informed the committee that '[f]rom

01-November-2009 to 31-October-2-14, 36.4% of selected verified incidents that

involved a firearm involved a handgun' for offences including offences against

the person, antisocial behaviour, criminal intent or conspiracy, harassment,

offences against animals and deception.[14]

3.15

In Victoria in 2013–14, there was a total of 688 offences where a

firearm was used, threatened or displayed including:

-

16 homicides;

-

8 rapes;

-

101 robberies;

-

356 assaults;

-

29 abductions or kidnappings; and

-

56 aggravated burglaries.[15]

3.16

Of the total offences involving the use of a firearm in Victoria in

2013–14, 39.5 per cent involved the use of a handgun.[16]

3.17

Data provided by Queensland Police for offences committed with the use

of a firearm over the period 2009–10 to 2013–14 showed a high rate of handgun

use in homicides (33 per cent), assaults (34–44 per cent), robbery (50–67 per

cent) and other offences against the person (23–42 per cent).[17]

3.18

Data on the use of stolen firearms in crime is derived from the National

Firearms Theft Monitoring Program (NFTMP):

Data provided by state and territory police indicated that

firearms from a very small percentage of theft incidents (less than 5%)

reported in the four year period 2005-06 to 2008-09 were subsequently used to

commit a criminal offence or found in the possession of a person charged with a

non-firearm related criminal offence. These data refer to firearms used in

crime in the 12 month period in which the firearm was reported stolen and hence

is likely an understatement of the true percentage.[18]

3.19

The following table sets out the use of stolen firearms in crime in

Australia from 2004-05 to 2008-09.[19]

|

Offence

type

|

Number

of theft incidents

|

|

Violent

crime and related offences

|

n

|

|

Armed

robbery

|

6

|

|

Murder/suicide

|

3

|

|

‘Home

invasion’

|

2

|

|

Attempted

murder

|

1

|

|

Manslaughter

|

1

|

|

Domestic

violence

|

1

|

|

Burglary

with assault

|

1

|

|

‘Ram

raid’

|

1

|

|

Other

offences

|

|

Modification

to firearm

|

2

|

|

Illegal

discharge of a weapon

|

2

|

|

Firearm

trafficking

|

1

|

|

Dangerous

conduct with a firearm

|

2

|

|

Illegal

firearm sale

|

1

|

|

Receiving

stolen property

|

1

|

|

Unlawful

possession

|

1

|

|

Drug

offences not further defined

|

4

|

|

Firearm

offences not further defined

|

3

|

|

Not

further defined

|

2

|

3.20

The ACC also provided the committee with data on the use of stolen

firearms then used in later criminal activity.[20]

As part of its trace program, it has conducted traces on 434 stolen firearms

(long-arms and handguns) seized after use in a crime, or with persons who were

not licensed to have them in their possession.[21]

|

Table 1 - Criminal

activity circumstances for traced firearms reported as stolen. Circumstances

|

Number

|

Percentage

|

|

Larceny

|

1

|

0.2

|

|

Parole Breach

|

1

|

0.2

|

|

Road Rage

|

1

|

0.2

|

|

Suspicious suicide

|

1

|

0.2

|

|

Vehicle Theft

|

1

|

0.2

|

|

Assault

|

2

|

0.4

|

|

Drive By Shooting

|

2

|

0.4

|

|

Extortion

|

3

|

0.7

|

|

Suicide

|

4

|

0.9

|

|

Conduct endangering life

|

5

|

1.1

|

|

Domestic Dispute

|

5

|

1.1

|

|

Homicide attempt

|

5

|

1.1

|

|

Homicide

|

10

|

2.2

|

|

Theft aggravated

|

14

|

3.1

|

|

Armed Robbery

|

16

|

3.6

|

|

Burglary

|

17

|

3.8

|

|

Firearm Trafficking

|

26

|

5.8

|

3.21

Firearms not only pose a significant threat to the community but also to

law enforcement authorities. Victoria Police explained that it mostly does not

know in advance where illicit firearms might be found and that illicit firearms

are largely detected through the investigation of other offences.[22]

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) held a similar view about the inability to

know when and where an illicit firearm might be encountered. The AFP told the

committee that, as an operational safety matter, its officers must consider the

risk that there is an undisclosed firearm at an incident:

Clearly, having stolen guns out in the community means that

we are unaware when we are responding and that the community is unaware of the

threat that may present itself, more generally. Where we have information in

relation to ownership of firearms, then, as a normal operating practice within

policing, we actually get information. So, if we were attending a domestic

disturbance, perhaps, then just as a matter of routine we will actually get

information as we are attending to that location as to whether there are any

firearms. We can determine who is known to live at that address and if there

are any firearms associated with that. Stolen firearms are outside of that

regime and will be unknown to us. And then, of course, there is the fact that

they are stolen and there is the potential that they have been diverted to the

criminal enterprises for their own ends and to protect themselves and to enable

them to undertake their enterprises. That presents a threat to us because, of

course, they are demonstrating an interest in using a firearm in order to

undertake their activities.[23]

Organised crime

3.22

A number of witnesses spoke about the links between firearms and

organised crime. The ACC noted that 'firearms will continue to be sought,

acquired and used by criminals, including those involved in organised crime, as

an enabler used to protect interests and commit acts of violence'.[24]

The ACC indicated that no single group dominates the sale and supply of

firearms to the illicit market but stated that 'firearms and organised crime

are inextricably linked'.[25]

The ACC referred to three ways in which such groups use firearms:

-

conflicts and territorial disputes over the management and

protection of drug turf and appropriation of 'protection' money;

-

the promotion of criminal image, reputation and status to support

their dominion; and

-

personal factors such as revenge, interpersonal or family based

conflicts.[26]

3.23

Dr Samantha Bricknell of the AIC explained the appeal of handguns in

particular for serious and organised crime groups:

...it is the view of law enforcement that handguns are the

weapon of choice amongst the criminal fraternity. That might be for a range of

reasons. Some interesting analysis that was done in the UK interviewing

offenders who had been convicted of firearm offences, and some of them were

gang members, showed handguns not only served a defensive role but also an

offensive and a symbolic function. There is this gun firearm culture that has

emanated within the UK and is probably occurring within Australia, where

handguns not only have the power to harm and to maim but also have that

symbolic function of to threaten and intimidate the person on the receiving end

of that threat. That is the view amongst law enforcement. They are also

concealable, they are easy to carry around, that sort of thing, and they can

pack a punch when needed to.[27]

3.24

NSW Police noted that while there are a number of semiautomatic handguns

on the market and in the hands of criminal groups, it would appear that

currently criminals are 'jealously guarding their weapons'.[28]

They also noted that such weapons are often seen as status symbols.[29]

Hotspot mapping

3.25

Some submitters recommended the use of "hotspot" mapping,

where analysts use retrospective data to identify areas with high levels of

crime. The Victims of Crime Assistance League recommended the use of hotspot

mapping:

...one of the interesting things you pull from the BOCSAR [Bureau

of Crime Statistics and Research] figures is certain local government areas

like Bankstown, Blacktown and Campbelltown have somewhere in the vicinity of

300 and 400 offences involving firearms each year. Some eight years ago the New

South Wales police embarked upon a system where they were trying to reduce the

incidence of personal violence in the suburbs. They started a hot spot mapping

program where they were seeing concentrations of various forms of crime. Having

mapped that, they then went to those particular areas to determine what was the

best way to resolve it. In some of those cases the result was they put in

street lighting and automatically took away the environment that allowed some

of these toerags to engage themselves in assaults. Hot spot mapping has some

great potential. It is something, though, that would have to be tied in with

well-generated statistics because, unfortunately, you cannot bundle all types

of firearm crimes into the same category.[30]

3.26

The concept of hotspot mapping and its use to identify areas with high

levels of firearm theft and burglary was endorsed by the Firearm Training and

Safety Council:

Again, one gets the feeling that the problems are localised.

If that is correct, then in fact it should be of assistance to law enforcements

on the one hand to focus their resources in those particular geographical

areas. Also...if in fact theft from lawful storage is a particular problem in an

area, we should know about it and then those people in that area—rather than

being subject to draconian and ridiculous increases in storage levels of

requirement—perhaps can harden up their particular storage regimes to the

effect that it will be harder and less attractive to people to perform these

thefts.[31]

3.27

The National Farmers' Federation also supported the idea, particularly

in the context of raising public awareness with regards to the safe storage of

firearms in areas where theft of firearms is prevalent.[32]

3.28

The AIC discussed some of the limitations involved with hotspot mapping,

though did not discount its benefits when utilised at a state and territory

level:

I understand that that is an issue that has been picked up by

some jurisdictions. I believe New South Wales may have done some hot-spot

mapping of where firearms are being used. In terms of its use it depends on the

concentration of those incidents. A hot spot is only of any use where you have

a concentration of incidents in time and space. If those hot-spot maps show

that instances are sparsely populated or spread out over time, while that may

be interesting from a statistical perspective, it really has limited utility in

terms of what can then be done with a hot-spot map of that kind. Really, by

undertaking a hot-spot analysis you are making the link between an incident and

the location and time essentially. So the question then becomes: what do you do

in those kinds of locations where those instances have occurred? I am not sure

the extent to which that particular kind of analysis is particularly useful for

understanding illicit firearms other than to identify there may be broad areas

where incidents are more likely to happen. But the next question is: what do

you then do? We do not have that kind of data. As far as I am aware, there are

no data sources available to be able to undertake national hot-spotting of that

kind. I think it is really probably only useful anyway at the jurisdictional

level.[33]

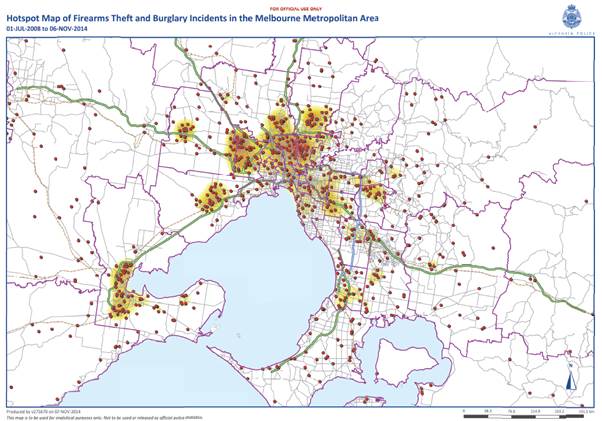

3.29

Victoria Police provided the committee with a number of hotspot maps,

such as that at Figure 3.1, to demonstrate how it has used the technique to

identify areas where there are high rates of particular crimes, including the

theft and burglary of firearms.[34]

Figure 3.1: Hotspot map showing

incidents of firearms theft and burglary

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page