Definition of disclosable conduct

5.1

This chapter considers various definitions of disclosable conduct. It

begins by comparing the current definitions across the PID Act, the FWRO Act

and the Corporations Act. It then examines potential reforms for the public and

private sectors.

Current arrangements

5.2

The definition of disclosable conduct in whistleblower legislation

currently varies between the PID Act (public sector regime), the regime under

the FWRO Act, and other private sector legislation such as the Corporations

Act.

5.3

For example, under the Corporations Act, disclosable conduct is limited

to contraventions of a provision of the corporations legislation.[1]

The recent additions of the whistleblower protections to the FWRO Act provide a

much broader definition of disclosable conduct than exists elsewhere in the

private sector. Section 6 of the FWRO Act defines disclosable conduct as

an act or omission that:

- contravenes, or may contravene, a provision of the FWRO Act, the FW Act)

or the CC Act; or

- constitutes, or may constitute, an offence against a law of the

Commonwealth.[2]

5.4

To be eligible for protection, a whistleblower would have to satisfy subsection 337A(1c)

of the FWRO Act by having reasonable grounds to suspect that disclosable

conduct as defined in section 6 had occurred. As a result, whistleblowing that

does not meet the threshold set out in section 6 is not afforded protection.

5.5

By contrast, the PID Act includes several provisions that set a lower

threshold for disclosable conduct, including: contraventions of a Commonwealth,

state, or territory law, corruption, abuse of public trust, wastage of public

resources and danger to health, safety or the environment.[3]

5.6

To assist consideration of potential reforms to definitions of

disclosable conduct, the committee examined the definitions of disclosable

conduct in the PID, FWRO and Corporations Acts against the seven levels set out

in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1: Potential definitions for disclosable conduct ranging

from narrowest definitions at the top to the broadest definitions at the bottom

of the table

| Possible levels for definitions of disclosable

conduct |

Responsibility for conducting investigations |

PID Act Section 29 |

FWRO Act Section

6 |

Corporations Act Section 1317AA(d) |

| 1) May be a Commonwealth Criminal offence |

AFP only |

Yes |

Yes |

Contravention of Corporations Act only |

| 2) May be a Commonwealth Civil offence |

AFP and the Commonwealth regulatory agencies responsible for that Act |

Yes |

Yes |

Contravention of Corporations Act only |

| 3) May contravene a Commonwealth law |

Commonwealth regulatory agencies responsible for relevant Acts |

Yes |

FWRO Act, Fair Work Act or Competition and Consumer

Act |

Contravention of Corporations Act only |

| 4) May contravene a Commonwealth, state or territory

law |

AFP, state and territory police and the Commonwealth, state and

territory regulatory agencies responsible for that Act |

Yes |

|

|

| 5) Breaches of registered or mandatory professional

standards and codes of conduct |

Regulators and bodies responsible for standards and codes of conduct |

Yes |

|

|

| 6) Breaches of voluntary professional standards and

codes of conduct |

Bodies responsible for standards and codes of conduct |

N/A |

|

|

| 7) Broad range of criteria including maladministration,

corruption, abuse of public trust, wastage, danger to health, safety or the

environment |

Organisation and regulators |

Yes |

|

|

Note: The shaded rows

indicate the level of disclosable conduct that the committee is recommending

should apply to all private sector organisations or businesses that are subject

to the Privacy Act 1988. Source: Acts as indicated in the table.

5.7

Table 5.1 shows the very broad coverage of the PID Act as well as the

broader coverage of the FWRO Act when compared to the Corporations Act. An

important question for the committee was where the threshold for disclosable

conduct should be set in order to target the most serious integrity risks. The

following section summarises information on disclosures that have been made

under current laws.

Types of disclosures that have been

made

5.8

This section summarises the types of disclosure that have been received

under the PID Act and the Corporations Act. As the FWRO Act whistleblower

protections only came into effect in May 2017, statistics for that are not yet available.

5.9

The Ombudsman's 2015–2016 Annual Report provides information (shown in

Table 5.2) on the types of conduct that has been disclosed under the PID

Act. The figures indicate that 33 per cent of disclosures relate to a breach of

a Commonwealth, state or territory law and that the remaining 67 per cent cover

a broad range of disclosures, many of which are below the threshold of

contravening a law.[4]

Table 5.2: Types of public sector disclosable conduct

reported in 2015–2016

| Type of

disclosable conduct |

Number of Instances (%) |

| Contravention of a law of the

Commonwealth, state or territory |

232 (33%) |

| Conduct that may result in

disciplinary action |

170 (24%) |

| Maladministration |

137 (19%) |

| Wastage of Commonwealth resources

(including money and property) |

45 (6%) |

| Conduct that results in, or that

increases, the risk of danger to the health or safety of one or more persons |

36 (5%) |

| Conduct engaged in for the purpose of

corruption |

25 (4%) |

| Abuse of public office |

21 (3%) |

| Perversion of the course of justice |

16 (2%) |

| Abuse of public trust |

14 (2%) |

| Other (conduct in a foreign country

that contravenes a law; fabrication, falsification, plagiarism or deception

in relation to scientific research; and conduct that endangers, or risks

endangering the environment) |

11 (2%) |

| Total |

707 (100%) |

Source: Commonwealth

Ombudsman, Annual Report 2015–2016, p. 73.

5.10

Of the 612 disclosures under the PID Act, decisions were taken not to investigate

145 (23 per cent) disclosures. The reasons for not undertaking investigations

include:

- the information does not concern serious disclosable conduct (37

per cent);

- the conduct has been or is already being investigated (27 per

cent);

- the discloser does not wish an investigation to be pursued (eight

per cent); and

- the disclosure was frivolous or vexatious (three per cent).[5]

5.11

The Moss Review noted that between 2013 and 2015, 1080 disclosures were

made, of which a number of instances identified significant wrongdoing, such

as:

- inappropriate pressure from an organisation's CEO to falsify

financial reporting;

- allegations of corruption within departments and portfolio

bodies, including 'kick backs' for using preferred suppliers;

- serious criminality, including drug trafficking and theft of

departmental IT equipment; and

- systemic patterns of wrongdoing amongst a group of public

officials posted together, such as allocating responsibilities to untrained

staff, consumption of alcohol while on duty, and fraudulently recording hours.[6]

5.12

ASIC's annual reports provide statistics on public interest disclosures

received by ASIC under the Corporations Act. In 2015–2016 ASIC received 146

disclosures. After preliminary inquiries, 80 per cent of disclosures were

assessed as requiring no further action, often due to insufficient evidence (36

per cent) or other investigations or processes already being underway (35 per

cent).[7]

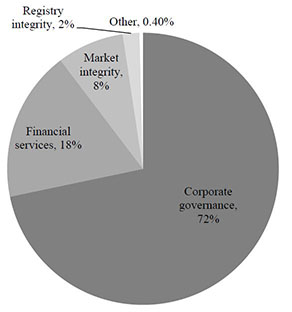

5.13

In its submission ASIC provided further detail, covering the period from

February 2014 to June 2016, as shown in Figure 5.3 below. The most common type

of disclosure was about corporate governance (72 per cent), which includes

insolvency matters, insolvency practitioner misconduct, contractual issues, and

directors' duties.[8]

Figure 5.3: Types of whistleblower reports received by

ASIC

Source: ASIC, Submission 51, p. 11.

Public sector

5.14

This section discusses potential reforms to the threshold for

disclosable conduct in the public sector.

Disclosures about personal employment

related matters

5.15

An area of concern with the PID Act as currently drafted is an apparent

over-representation of minor personal employment related matters that may be

better dealt with through dispute resolution or merits review mechanisms rather

than being treated as a public interest disclosure.

5.16

For example, in its 2014–2015 Annual Report, the Commonwealth Ombudsman

stated that enquiries to the Ombudsman indicate:

Enquiries to our office indicate an over-representation of

PIDs that are about conduct relating to relatively minor personal grievance

matters, many of which are employment related and/or have already been through

other processes available to the discloser.

The Commonwealth PID scheme is not alone in this regard as

other Australian PID oversight bodies have observed a similar trend with

schemes in other jurisdictions.[9]

The Moss Review

5.17

A statutory review of the PID Act conducted by Mr Philip Moss (Moss Review)

in 2016 was, amongst other things, tasked with considering 'the breadth of

disclosable conduct covered by the Act, including whether disclosures about

personal employment-related grievances should receive protection under the Act'.[10]

5.18

In examining this matter, the Moss Review found that:

Submissions received from agencies noted that the

overwhelming majority of disclosures concerned issues like workplace bullying

and harassment, forms of disrespect from colleagues or managers, or minor

allegations of wrongdoing.[11]

5.19

However, the Moss Review also noted that it is difficult to identify

clearly within the Commonwealth Ombudsman's annual report what proportion of

disclosures primarily relate to interpersonal conflicts at work or a personal

employment-related grievance.[12]

5.20

Furthermore, the Ombudsman's Annual Report indicates that in 2013–2014, 38 per

cent of the 223 investigations conducted across the Commonwealth public sector,

concerned disclosures about an employment or code of conduct related matter,

which can be investigated under the Public Service Act 1999 or the FW

Act.[13]

5.21

The Moss Review argued that the PID Act was ill-suited as a mechanism

for resolving conflict over minor personal employment-related matters:

The PID Act does not provide resolution for grievances, and

the allocation and investigation process (which, under the statutory framework,

may take up to 104 days to complete in total and longer if the Commonwealth

Ombudsman or the IGIS grants the agency an extension) can prolong the discloser's exposure to the situation that they

have reported.[14]

...the PID Act's processes and procedures are not well adapted

to resolving allegations of less serious disclosable conduct. For example, the

extensive protections against reprisal and secrecy offences can have an adverse

effect upon best practice conflict-management solutions that emphasise

alternative dispute resolution or merits review processes, rather than formal

investigation.[15]

5.22

As a consequence, the Moss Review concluded that the PID Act threshold

should be targeted at the most serious integrity risks, such as fraud, serious

misconduct or corrupt conduct. The Moss Review advocated that solely personal

employment related grievances should be excluded from the PID Act unless they

relate to systemic issues or reprisals.[16]

5.23

However, the Moss Review added an important caveat to the above finding

by recognising that there are cases where a personal employment matter is bound

up with a matter that may properly be the subject of a public interest

disclosure. In these circumstances, the Moss Review found that the public

interest matter should still qualify for disclosure under the PID Act:

These amendments will need to ensure that in cases when a

disclosure that includes both an element of personal employment-related grievance,

as well as an element of other wrongdoing, the latter element could still be

the subject of a PID.[17]

5.24

Alternative approaches to dealing with the issue of minor personal

employment matters were put forward to the Moss Review. For example, some

submitters to that review recommended the inclusion of a public interest

criterion for a disclosure to be accepted as a public interest disclosure.[18]

The powers of the Commonwealth Ombudsman

5.25

One of the areas where there appears to be a misconception

amongst some submitters to this inquiry relates to the powers of the Commonwealth

Ombudsman under the PID Act.

5.26

Under the PID Act the Commonwealth Ombudsman is included in the definition

of an 'investigative agency'.[19]

However, the Commonwealth Ombudsman noted that it is not authorised to

investigate action taken with respect to a person's employment in an agency or

prescribed authority:

This limits the Ombudsman's capacity to comprehensively

review how agencies deal with public interest disclosures about most employment-related

conduct. In such cases, the Ombudsman can generally only investigate whether

agencies applied the procedural requirements of the PID Act in dealing with the

disclosure. The Ombudsman is precluded from investigating and/or forming a view

about the adequacy or outcome of the agency's investigation of the substantive

disclosure.[20]

5.27

The committee notes that section 22 of the PID Act already provides for

a public interest disclosure to be treated as a workplace right under the FW

Act. The Commonwealth Ombudsman noted that:

This gives an employee access to the Fair Work Commission for

remedies in the case of adverse action by their employer linked to them having

made a public interest disclosure.[21]

Committee view

5.28

Given the findings of the Moss Review, the committee considers it

important to ensure that any changes to whistleblower protections remain

focussed on the most serious integrity risks.

5.29

However, the committee remains concerned that the most likely forms of

reprisal are employment related. Therefore any amendments should ensure that

employment related reprisals can still be dealt with under the PID Act.

5.30

In addition, the lack of clear information on what proportion of

disclosures are actually related to personal employment matters is of concern.

The committee considers the data should be collected and assessed before any

legislative changes are made.

Recommendation 5.1

5.31

The committee recommends that, in implementing the Moss Review

recommendation regarding employment related matters care is taken to ensure

that:

-

allegations of reprisal action taken against a person that has

made a public interest disclosure can still be dealt with under a Whistleblowing

Protection Act; and

-

data is gathered and assessed in a national database on the proportion

of disclosures that are personal employment related, but that this not have to

occur before any legislative changes are made as recommended in this report.

Private sector

Definition of disclosable conduct

in the private sector

5.32

This section summarises evidence provided to the committee on the

definition of disclosable conduct for the private sector. In brief, the

majority of submitters that addressed this matter argued that the current

definition of disclosable conduct in the private sector should be broadened. At

a minimum, these submitters argued that disclosable conduct under any proposed

legislation for the private sector should include potential breaches of any

Commonwealth, state or territory law.

5.33

For example, the ACCC argued for disclosable conduct to include

potential breaches of a Commonwealth, state or territory law.[22]

5.34

The AICD suggested that the definition of disclosable conduct should be

extended in the context of corporate entities to include:

- contraventions of the Corporations Act; and

- offences against any Commonwealth, state or territory law.[23]

5.35

The AICD explained that the reason it considers disclosable conduct

should be as broad as any Commonwealth or state or territory law is that a

whistleblower cannot be expected to be an expert on the Corporations Act and that

they should not have to consult a piece of legislation before they make a

report:

If a whistleblower is a witness of serious corporate

wrongdoing, they should feel confident in making a disclosure to their company

or to an appropriate regulator, without fear that it might fall outside the

definition because of a technicality.[24]

5.36

Several submitters were of the view that private sector whistleblowing

legislation should include, in some form, the law of foreign countries within the

definition of disclosable conduct. The GIA favoured broadening the definition

of disclosable conduct to include 'conduct that contravenes a law of the

Commonwealth, a state or a territory', as well as some conduct that contravenes

foreign laws.[25]

Similarly, the AICD suggested that disclosable conduct include offences against

the law of a foreign country that is also in force in Australia.[26]

5.37

A key concern for several submitters and witnesses was the potential

inability of the proposed legislation to encourage the disclosure of

significant wrongdoing that was clearly unethical and harmed consumers, but was

not necessarily illegal, if the definition of disclosable conduct was

restricted to breaches of any Commonwealth, state or territory law.

5.38

For example, ASIC suggested that the scope of information protected by

the whistleblowing provisions in the Corporations Act should be broadened to

cover any misconduct that ASIC may investigate.[27]

5.39

Similarly, Mr Dennis Gentilin pointed out that the definition of

disclosable conduct would need to include unethical but not necessarily illegal

behaviour if the disclosure of the conduct unearthed in recent financial

scandals is to be protected by private sector whistleblowing legislation:

...my understanding is that a disclosure must relate to conduct

that '(a) contravenes, or may contravene, a provision of this Act, the Fair

Work Act or the Competition and Consumer Act 2010; or (b) constitutes, or may

constitute, an offence against a law of the Commonwealth.' My concern is that this

is not sufficiently broad.[28]

In many instances whistleblowers expose wrongdoing that is

clearly unethical but not necessarily illegal or in contravention of the

aforementioned Acts. The recent events at CommInsure provides one example of

this. Although the wrongdoing in that organisation clearly caused hardship to

consumers and was unethical, a recent investigation by ASIC did not find any of

the conduct to be illegal. If possible legislation must also protect

whistleblowers in these types of scenarios.[29]

5.40

The AIST argued for the definition of disclosable conduct to include

actual or suspected contravention of applicable statutory provisions, or a law

of the Commonwealth, fraud, gross mismanagement, and financial misconduct

including misappropriation of funds.[30]

5.41

Professor A J Brown identified the definition of disclosable conduct as the

most important reform priority. He argued that the private sector definition of

disclosable conduct needed to encompass ethics if whistleblower protections

were to cover the corporations and financial services issues which have

attracted the attention of the committee during this and previous parliaments.[31]

5.42

Professor Brown was of the view that the definition of disclosable

conduct in the FWRO Act would substantially increase the likelihood that

protection could be offered to whistleblowers involved in recent scandals in

the financial services sector. However, he noted that while breaches of the law

might be suspected, the evidence may only emerge after disclosures have been

made based on breaches of professional standards, operating procedures or

ethical standards.[32]

5.43

Professor Brown also considered that there were unlikely to be any

constitutional limitations to broadening the definition of disclosable conduct,

provided that the definition:

...can be safely characterised as laws with respect to the

proper governance of corporations (i.e. ‘constitutional corporations’ under

section 51(xx) of the Constitution), or to the employment or working conditions

of employees or officers of corporations, or as incidental to the enforcement

or implementation of other valid Commonwealth laws or regulations.[33]

Low level and personal

employment-related matters

5.44

As with the public sector, concerns were expressed about designing a

scheme for the private sector with sufficient care so that solely personal

employment-related matters did not unnecessarily become the subject of public

interest disclosures.

5.45

For example, Ms Louise Petschler, General Manager of Advocacy for the

AICD pointed out that a whistleblowing framework within an organisation would

likely capture a broad range of lower-level matters such as employee-manager

disputes, and employment grievances. She therefore suggested that internal

whistleblower procedures would need to be set up so that disclosures which met

the criteria were dealt with, while lower-level matters and personal employment

grievances were managed appropriately.[34]

Committee view

5.46

The vast majority of the evidence to the committee from a broad range of

submitters and witnesses argued that the current private sector definitions of

disclosable conduct are too narrow for the effective identification of

misconduct and protection of whistleblowers.

5.47

Based on the evidence before it, the committee considers that there is

support for the definition of private sector disclosable conduct to be

broadened to include any contravention of a law of the Commonwealth or the

states or territories where:

- the disclosure relates to the employer of the whistleblower and

the employer is an entity covered by the FW Act; or

- the disclosure relates to a constitutional corporation;

- but not where the disclosure relates to a breach of law by the

public service of a state or territory; and

- further, disclosable conduct should also include any breach of an

industry code that has force in law or is prescribed in regulations under a

Whistleblowing Protection Act.

Recommendation 5.2

5.48

The committee recommends, in relation to whistleblower protections for

the private sector, including the corporate and not-for-profit sectors, that

disclosable conduct be defined to include:

-

a contravention of any law of the Commonwealth; or

-

any law of a state, or a territory

where:

-

the disclosure relates to the employer of the whistleblower and

the employer is an entity covered by the Fair Work Act 2009; or

-

the disclosure relates to a constitutional corporation; and

-

any breach of an industry code or

professional standard that has force in law or is prescribed in

regulations under a Whistleblowing Protection Act;

-

but not where the disclosure relates to a breach of law by the

public service of a state or territory.

5.49

While noting that the above definition of disclosable conduct is broader

than current definitions for the private sector in most cases, the committee is

concerned that the definition recommended above may still be insufficient to

provide protection to whistleblowers who may be involved in disclosing conduct

similar to that revealed in many of the financial sector scandals in recent

years.

5.50

The committee therefore recommends that the government examine the

feasibility of broadening the above definition of disclosable conduct. The

committee notes, however, that within the scope of its own inquiry, it has had a

limited capacity to examine the constitutional capacity of the Commonwealth to legislate

beyond any breach of a law of the Commonwealth, states or territories.

Recommendation 5.3

5.51

The committee recommends that the government examine whether the

Commonwealth has the constitutional power to include additional lower

thresholds for disclosable conduct that would adequately protect whistleblowers

such as those involved in scandals in the financial service sector in recent

years.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page