Stillbirth reporting and data collection

4.1

There is no systematic approach to reviewing and reporting stillbirths

across Australia. This lack of standardisation and coordination has significant

implications for research and education aimed at preventing future stillbirths.

4.2

The collection and analysis of data to determine trends in the rate,

risk factors and underlying causes of stillbirth over time is important for

understanding how stillbirth rates may be reduced, and provides direction for

future research, education and preventive efforts. Data collection

needs to encompass a wide range of factors in order to inform stillbirth

prevention strategies.

4.3

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that around 60 per cent of

countries do not have adequate systems for counting births and deaths, and has

produced Making Every Baby Count, a guide for the audit and review of

stillbirths and neonatal deaths.

By counting the number of stillbirths and neonatal deaths,

gathering information on where and why these deaths occurred and also by trying

to understand the underlying contributing causes and avoidable factors,

health-care providers, programme managers, administrators and policy-makers can

help to prevent future deaths and grief for parents, and improve the quality of

care provided throughout the health system.[1]

4.4

The current process to develop a National Strategic Approach to

Maternity Services, initiated by the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory

Council (AHMAC), acknowledges that a national perinatal audit program is yet to

be implemented.[2]

4.5

This chapter discusses the quality and scope of stillbirth reporting and

data collection, and considers inconsistencies, gaps, costs, access and

timeliness in Australia's stillbirth reporting and data collection system, as

well as issues relating specifically to autopsies and other post-mortem

investigations.

Quality and scope of data

4.6 The Department of Health funds the Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare (AIHW) to collect data from each jurisdiction as part of the National

Perinatal Data Collection (NPDC), undertake data analysis and prepare reports

on perinatal deaths, including stillbirths. The AIHW has produced Stillbirths

in Australia, 1991−2009,

and publishes biennial reports on perinatal mortality. The most recent detailed

data available is for 2013−14.[3]

4.7

The most recent consolidated report, Perinatal Deaths in Australia

1993−2012,

provides an overview of the characteristics and causes of stillbirth and

neonatal deaths in Australia at a population level, and identifies trends and

changes in perinatal mortality over time.[4]

4.8

In its 2009 review of the Maternity Services Plan, the Department of

Health identified that data gaps were a significant issue, and established the

National Maternity Data Development Project (NMDDP) to develop a nationally

consistent maternal and perinatal data collection.

Stage 1 (2011−13)

prioritised data gaps and inconsistencies in the existing NPDC, and included a

National Perinatal Mortality Data Reporting Project to identify options for

collecting and reporting national perinatal mortality data. Stages 3 and 4 of

the NMDDP (2015−17)

included the development of nationally consistent maternal and perinatal

mortality data collection in Australia with standardised data specifications,

annual reporting and data base development.[5]

4.9

However, a number of witnesses and submitters identified continuing

problems affecting the quality, scope, timeliness and accessibility of

stillbirth data.

Inconsistencies in perinatal data

collection and reporting

4.10

The Centre of Research Excellence for Stillbirth (Stillbirth CRE) stated

that the current national practice for stillbirth reporting data collection is

'suboptimal', with significant implications for the quality of research

outcomes and policy decisions.

Major impediments to timely, quality data to inform effective

prevention strategies for stillbirth include significant duplication of effort

and disparate approaches across and within states and territories.[6]

4.11

The National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit (NPESU) at the

University of New South Wales (UNSW) reported on the difficulty of identifying

research priorities when access to national data is 'highly constrained' and

national reporting lacks detailed results.[7]

The lack of consistent ongoing funding for epidemiological

research and reporting of stillbirth in Australia is hampering the ability to

undertake this important research in Australia. The current restrictive

processes for standardised national collection of data about pregnancy and

birth have resulted in a national reporting system that is unresponsive to

change, is delayed and lacks clinically meaningful and relevant information to

assist clinicians in making changes to reduce the rate of preventable

stillbirth. Improvements in the timeliness of and access to national data on

pregnancy and birth are vital if we are to improve outcomes for mothers and

babies and reduce the rate of preventable stillbirth in Australia.[8]

4.12

The NPESU also noted that it had prepared a report for AIHW in 2016,

although this report has not been published. The report examined options for

improving perinatal mortality data collection and reporting in Australia,

including consultation with perinatal data custodians.[9]

Stillbirth datasets

4.13

Australia has two national datasets that record stillbirth in different

ways and produce different results, as follows:

- The AIHW is responsible for collating 'health' data on stillbirths in

Australia. The AIHW collates data in the NPDC and the National Perinatal

Mortality Data Collection (NPMDC), drawn from state and territory health authorities

under individual data agreements between the AIHW and each state and territory.[10]

-

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) sources data from state and

territory registries of Births, Deaths and Marriages and tabulates information

on perinatal deaths, including stillbirths, as part of the Causes of Death,

Australia (ABS Cat No. 3303.0) report, which is released annually.[11]

4.14

In addition, the National Hospital Morbidity Database is a collection of

electronic confidential summary records in public and private hospitals in

Australia, compiled from data supplied by state and territory health

authorities.[12]

4.15

These large population datasets are important for stillbirth research,

particularly for undertaking large-scale epidemiological research using modern

big-data analytics to determine why stillbirths occur and how to prevent them.

However, data collected by the ABS generally shows lower rates of stillbirths

than that collected by the AIHW, owing to the way that stillbirth is, or is

not, accounted for in births and deaths in individual states and territories.

For example, the ABS reported 23.8 per cent fewer stillbirths for 2013−14 than reported by

AIHW.[13]

As NPESU noted:

Rates of stillbirth vary depending on which national source

is used, with the ABS data known to significantly under-report the rate of

stillbirth in Australia[14]

4.16

The under-reporting of stillbirths by the ABS is largely attributable to

the two-step verification process required to fully register a stillbirth: the

Medical Certificate of Cause of Perinatal Death issued by the attending

clinician, and a statement from the parents. If only one notification is

received, a partial registration is recorded.[15]

Mr James Eynstone-Hinkins, Director, Health and Vital Statistics, ABS, outlined

the process as follows:

We collect information on all stillbirths registered through

the registries of births, deaths and marriages in line with the same method

used internationally for collecting information on perinatal deaths. The

registration criteria in Australia for stillbirths are 20 weeks gestational age

or 400 grams birth weight. That aligns with the Australian criteria and the ABS

inclusion criteria. The causes of stillbirths and neonatal deaths are recorded

on the medical certificate of cause of perinatal death. This captures the main

condition in the infant and the main condition in the mother as well as any

other relevant conditions. Causes are coded in accordance with the

international classification of diseases, according to coding rules governed by

the World Health Organization and used by WHO member states. The data that we

capture is released approximately nine months after the end of a reference

period, which roughly equates to a calendar year. That is released as aggregate

data as part of the national causes of death data set.[16]

4.17

The statutory instruments and registration practices related to

registration of births and perinatal deaths vary between jurisdictions. There

are also variations in the reported causes of stillbirth. ABS data shows the

number of unexplained stillbirths as three times that reported by AIHW (ABS, 64

per cent compared to AIHW, 20 per cent) as a result of ABS using information on

the death certificate at the time of stillbirth and prior to the result of any

investigation into the causes. AIHW data, on the other hand, is based on

classification of causes following review of all available post-mortem

investigations.[17]

Mandatory and voluntary items

4.18

Some data in the NPDC is mandated by the National Health Information

Standards and Statistics Committee for collection under agreements between the

Commonwealth and each state/territory as part of the National Minimum Data Set

(NMDS).[18]

4.19

A national committee, the National Perinatal Data Development Committee,

comprising the PDC custodians from each state and territory and the AIHW,

manage what is included in the NPDC and which data items are mandated for

collection in all jurisdictions. Each jurisdiction must agree to add a new item

and commence collection and reporting otherwise data are collected on a

voluntary basis and may differ between jurisdictions.

4.20

The AIHW noted that the Perinatal Mortality Committee uses data from

jurisdictional perinatal mortality committees about the circumstances of a

baby's death, the social history of the family and the professional care of the

mother, and advised that it is working towards including this data in national

reports 'as the quality of the data collected improves'. However, it also noted

a high proportion of responses for certain items are 'not stated' because they

are of a voluntary nature.[19]

4.21

Dr Fadwa Al-Yaman, Group Head, Indigenous and Maternal Health Group,

AIHW, explained why there are delays in adding a new item to the national

collection. The AIHW is required to determine what data are clinically relevant

and appropriate by consulting with clinical experts, and defining the

additional items based on national and international standards and guidelines. The

AIHW then seeks agreement with the jurisdictions and clinical experts through a

national committee. Once agreed, the new specifications are sent to the states

and territories. In some jurisdictions, the new items are already collected. In

other cases, the data may need to be collected 'from scratch', requiring

changes to that jurisdiction's system of data collection. The AIHW allows six

months for this new information to be collected, but delays in receiving the

new data from the states and territories may lead to delayed publication of the

national dataset.[20]

4.22

The NPESU argued that the information used for national stillbirth and

neonatal death reporting 'is missing vital information to allow for

comprehensive analysis, due to a lack of mandated standardised data items'.[21]

Inconsistent definitions

4.23

Within Australia, registration of stillbirths occurs at a state and

territory level, and each jurisdiction has its own register of births and

deaths and legislation defining what is registered as a birth or death in ABS

data. There is, for example, no standardised definition of what constitutes a 'live

birth' across the jurisdictions, making it difficult to distinguish between a

termination of pregnancy, a stillbirth and a live birth.[22]

4.24

All states and territories, except for Western Australia (WA), register

stillbirths only as births. WA registers a stillbirth as both a birth and a

death. South Australia (SA) does not include termination of pregnancy after 20

weeks in its legislative definition of 'birth'.[23]

4.25

Victoria is the only state that offers access to late term termination

between 20−24

weeks on request (without a referral or doctor’s approval).[24]

This means the rate of stillbirth for Victoria appears high in comparison to

other jurisdictions (9.1 per 1000 births in 2013−14,

compared to 7.1 per 1000 for the whole of Australia).[25]

4.26

In addition, lower populations and smaller numbers of births and

stillbirths can lead to significant variations in stillbirth rates over time,

which may be misleading. This is particularly relevant in considering the

higher rates of stillbirth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and

culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) populations in Australia.[26]

4.27

There is also a lack of consistency in how risk factors are classified

across different jurisdictions, suggesting that this may be the result of

different data and evaluation processes being used.[27]

4.28

As a result, stillbirth data are recorded differently making it

difficult to determine the rate of stillbirths across Australia. This is

especially problematic where a woman moves from her place of residence in one

jurisdiction in order to give birth in another jurisdiction.[28]

4.29

This issue is noted in the Australian government's latest report on

Sustainable Development Goals Indicators.

Various definitions are used for reporting and registering

perinatal deaths in Australia. The National Perinatal Data Collection defines

perinatal deaths as all fetal deaths (stillbirths) and neonatal deaths (deaths

of liveborn babies aged less than 28 days) of at least 400 grams birthweight or

at least 20 weeks’ gestation. Fetal and neonatal deaths may include late

termination of pregnancy (20 weeks or more gestation). Perinatal and fetal

death rates are calculated using all live births and stillbirths in the

denominator. Neonatal death rates are calculated using live births only.

Neonatal deaths may not be included for babies transferred to another hospital,

re-admitted to hospital after discharge or who died at home after discharge.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) has established a

separate National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection to capture complete

information on these deaths.[29]

4.30

The AIHW divides perinatal outcomes into three categories: stillbirths,

live born neonatal survivors, and neonatal deaths, as follows:

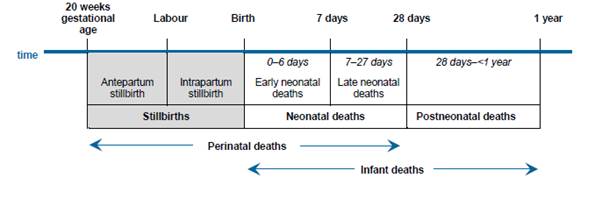

Figure 4.1: Perinatal death periods

for reporting in Australia[30]

4.31

Stillbirth CRE argued that the lack of consistent definitions for many

data items impacts on the accuracy of comparisons across jurisdictions and the

capacity to identify key outcomes. It also leads to a time lag of two to three

years between data collection and publishing in state/territory and national perinatal

mortality reports.[31]

Inadequate reporting standards

4.32

International studies have shown that inadequate information relating to

the timing of the stillbirth and other details in relation to pregnancy and

birth, maternal risk factors, obstetric and other conditions limits the value

of data for evaluating and implementing preventive strategies.[32]

4.33

According to Australian researchers, the data collected by the AIHW are

not comprehensive, consistent nor detailed enough to enable the information to

be used in meaningful ways to improve clinical care. This is due to a number of

factors, including that a number of items in the data collections are voluntary

(as noted above), which correlates with a higher rate of 'unknown' or

'unspecified' for those items.[33]

4.34

Stillbirth Foundation Australia highlighted the need to break Australian

stillbirth data down to a more granular level of analysis in order to

understand trends, and to make this data available to the private sector,

researchers and relevant organisations to encourage a more collaborative

environment.[34]

4.35

Having access to granular data is particularly important in giving a

greater understanding of where research needs to be concentrated, particularly

amongst rural and remote, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and women from

CALD backgrounds for whom there is an elevated risk of stillbirth and other

adverse pregnancy outcomes.[35]

4.36

Gestational age at birth, for example, is only reported nationally in

completed weeks of gestation, which is an impediment to researching the impact

of gestational age. '[M]ortality differences between 41.0 weeks' and 41.6

weeks' are of clinical significance but treated the same in a data collection

that records only "completed weeks"', that is, both are recorded in

data collections as 41 weeks' gestation.[36]

4.37

The NPESU noted that the lack of granular data has disguised the fact

that there have been some improvements in stillbirth trends amongst particular

age groups.

...national reporting indicates that there has been relatively

little change in the overall stillbirth rate in Australia over the past 20

years...However, more in depth statistical analysis undertaken by the NPESU...has

shown that improvements have been made in the risk of stillbirth at later

gestational age groups, and the inclusion of terminations of pregnancy and

reporting overall rates of stillbirth (rather than at different stages of

pregnancy) in national statistics has masked some of the inroads gained.[37]

4.38

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and

Gynaecologists (RANZCOG) considered that '[i]t is a serious deficiency of the

national perinatal data set (and some state perinatal data sets), that maternal

height and weight is not recorded'.[38]

RANZCOG submitted that such customisation of data could be used to better

predict the risk of fetal growth restriction, for example, and that 'not

collecting critical data impairs important research'.[39]

4.39

RANZCOG also noted, in relation to antenatal testing of fetal genetic,

chromosomal and structural conditions, that there is an 'absence of national

data collection in this critically important area of maternity care...[which] can

assist in the prevention of mortality and long-term morbidity through measures

being put in place around birth or early in the neonatal period'. Given that fetal growth restriction is the single largest cause of

unexplained stillbirth, RANZCOG argued there was an urgent need to adopt

'severe intra-uterine growth restriction in a singleton pregnancy undelivered

by 40 weeks' as a core maternity indicator in the National Core Maternity

Indicators.[40]

4.40

Professor Euan Wallace, Carl Wood Professor and Head of Department of

Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Monash University, stated that women from migrant

backgrounds are significantly under-represented in stillbirth data, including

second generation South-East Asian women who migrated to Australia following

warfare in their countries and who are recorded as Australian.

Those women are disproportionately represented in our

stillbirth data, yet our data collection systems are blind to maternal and

paternal ethnicity. We collect country-of-birth information of mothers but we

don't collect ethnicity.[41]

4.41

Dr Jane Warland also noted that data collected on stillbirth generally omitted

information about the father, even though he contributed half of the baby's DNA

and his ethnicity and age are likely to be important.[42]

Lack of data for rural, regional

and remote Australia

4.42

There are almost seven million people living in rural, regional and

remote Australia yet, as the AIHW review found, babies born to mothers living

in these areas are 65 per cent more likely to die during the perinatal period

than babies born to mothers living in major cities or inner regional areas.

Indeed, the further away women are from a major city, the higher the rate of

stillbirth.[43]

4.43

The National Rural Health Alliance called for improved data collection

quality, consistency and dissemination so that it can be used to improve rural

and remote maternal health outcomes and reduce perinatal deaths as well as

improving quality and safety of care, identifying lessons learned and

translating research into clinical practice and shared knowledge.[44]

4.44

Ms Victoria Bowring, Chief Executive Officer, Stillbirth Foundation

Australia, pointed to the need for more granular data in order to be able to

concentrate research in areas where there is inadequate data. Rural and remote

communities do not have access to the same level of health care as others, yet

there is no data to establish the extent to which such communities are at

higher risk of stillbirth.

It's one thing to submit a figure that is the sum total for a

nation at the end of a five-year period, but, if we had access to where these

are occurring—family history, background, location and all of those finer

details—it gives a greater understanding of where the research needs to be

concentrated.[45]

Difficulty and cost of accessing

data

4.45

The AIHW does not own the data contained in the NPDC, which is a collation

of all the state and territory Perinatal Data Collections (PDC, also known as

Midwives Data Collections). The data are therefore owned by the jurisdictions.[46]

4.46

The NHMRC has an Open Access Policy which aims to 'mandate the open

access sharing of publications and encourage innovative open access to research

data'.[47]

Recipients of NHMRC grants must comply with this policy.

4.47

However, given the relatively low numbers of stillbirth, researchers

wishing to access stillbirth data on a national scale need to seek agreement

from each jurisdiction each time they require it. This can be a lengthy and

costly process that extends beyond the time available to researchers dependent

upon three-year research funding cycles.[48]

4.48

According to the NPESU, the cost of accessing data ranges from $12 000

to $25 000, depending on the nature of the data requested. In

addition, it can take three to five years just to obtain the necessary

jurisdictional, national and ethical approvals required by AIHW to access

national perinatal data.[49]

4.49

Similarly, the Western Australian Perinatal Epidemiology Group noted

that the 'costs of obtaining de-identified linked data from government are

increasing and are approximately 10 per cent of a requested research

budget...Preferably, provision of [this] data for research should be considered a

core government service and therefore not cost recovered', as is the case in

the United States of America (USA).[50]

4.50

Mrs Ellana Iverach noted that the information derived from medical

reviews and investigations of a stillbirth was difficult to locate, and that it

should be more easily accessed so that it can be made available to researchers

and other interested parties.[51]

4.51

The NPESU pointed to the Vital Statistics Online Data Portal used in the

USA which offers a best-practice perinatal data collection model that is a far

simpler and cheaper for researchers to access.

The tortuous process for accessing national perinatal data in

this country stands in stark contrast to access to perinatal data in the USA

where birth, cohort and period linked birth and infant death, cause of death

and fetal death data are made available for independent research and analyses

and can be downloaded free of charge. The level of detail exceeds that

available in Australia.[52]

Timeliness of data

4.52

Access to timely, high-quality data on causes and contributing factors

to stillbirth are crucially important, not only for helping bereaved parents to

understand what happened and to plan for future pregnancies, but also to inform

the development of targeted prevention strategies.[53]

4.53

However, several submitters raised the negative impact of delayed access

to data on the ability of researchers to identify and address emerging issues

relating to stillbirth.[54]

The NPESU noted the long delays involved in adding new data items to the NPDC.

While having a NMDS is vital to ensuring consistency of

reporting across the country, the process of adding new data items to the

collection, gaining agreement from all jurisdictions and proceeding through the

data development processes means it can take up to 5 years or longer before an

item is mandated for collection and then a further 2 years before it might

appear in a national report. This is very relevant to the issue of reporting of

stillbirth data in Australia.[55]

4.54

Based on information reported to the AIHW by states and territories,

most stillbirths in Australian hospitals are reviewed by a hospital-level

committee and then a jurisdiction-level perinatal mortality review committee.[56]

4.55

However, the AIHW cited delays in provision of data by states and

territories as the reason for the delay in reporting, and indicated that it

would publish detailed data from 2015 by the end of the 2018 calendar year with

the intention to update perinatal deaths data online annually from 2019.[57]

4.56

In 2016, the NHMRC published Principles for Accessing and Using Publicly

Funded Data for Health Research. The principles were developed to 'improve the

consistency and timeliness of data available to researchers'.[58]

4.57

Professor Wallace noted that, whilst Australia has a secure system in

place for sharing sensitive data known as Secure Unified Research Environment

(SURE), the timeliness of data is inhibited by a lack of resources available for collating and linking perinatal data.[59]

4.58

Timely data are also considered crucial for identifying areas of substandard

care that may contribute to stillbirth.

4.59

Stillbirth CRE reported that it had developed, in partnership with the

Victorian Department of Health, an online system for national perinatal

mortality audits designed to enhance investigation and reporting of stillbirths

by providing timely data that will enable substandard care to be identified and

addressed. 'In both New Zealand and the United Kingdom (UK) national audit data

and timely feedback has led to reduced perinatal deaths through quality

improvement.'[60]

Linked datasets

4.60

Associate Professor Georgina Chambers, Director, NPESU, Centre for Big

Data Research in Health and School of Women's and Children's Health, Faculty of

Medicine, UNSW, noted that the NPESU has analysed stillbirth and neonatal data

across jurisdictions and identified the discrepancies between the different

datasets. She recommended that Council of Australian Governments should

prioritise the harmonisation, sharing and centralisation of health data to

establish comprehensive, standardised NPMDC.

Because Australia is a federation of states and territories,

we understand it is challenging to bring together a standardised set of data

items related to perinatal deaths that can be used not only by health systems

but also by researchers. It takes five years for a new mandatory item to be

added to the state perinatal data collections and at least another two for that

item to be reported on. A comprehensive perinatal mortality data collection

should routinely link to other datasets—such as the various registries of

births, deaths and marriages—to improve surveillance and should be integrated

with the national maternity mortality audit tool that was developed by the

Mater Research Institute and PSANZ. The NPESU laid the basis for comprehensive

data collection when we prepared the first perinatal mortality report in 2016.

Creating such an important dataset would not be difficult; it just takes

commitment and leadership from all involved.[61]

4.61

The AIHW noted that data gaps in the perinatal mortality collection

could be addressed by linking data to established collections, such as linking Medicare

Benefits Schedule (MBS), Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and NPDC data.[62]

4.62

The Population Health Research Network (PHRN), funded under the National

Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy to build linkages between

datasets in privacy-preserving ways, advised that seven of the eight states and

territories routinely link perinatal and death data to other administrative

data collections. These linked collections include MBS and PBS data, as well as

clinical trial and other researcher datasets, and recommended that researchers

should be made more aware of these linked, multi-jurisdictional resources.[63]

4.63

The PHRN noted that a more detailed understanding of stillbirth could

also be gained by linking death and perinatal data with data from other sources,

such as hospital admissions and emergency department admission. However,

several challenges remain in achieving coordinated datasets across

jurisdictions as a result of different legislation and policies and reluctance

by some jurisdictions to share identifiers across borders. The PHRN noted that

a project is underway that may address these issues and seeks to improve

linkages between state/territory data collections and the Commonwealth data

collections through the AIHW.[64]

To get the full picture on health in Australia we need to be

able to bring those together. Australia can already bring that data together,

but it generally does it in a way that we would describe as create and destroy.

Those linkages are not maintained. The good news is that we are making good

progress with systematically linking that data, and I think it won't be too

long before we have that data available to researchers.[65]

4.64

Ms Belinda Jennings, Senior Midwifery Advisor, Policy and Practice,

Katherine Hospital noted that, whilst midwives across Australia contribute to a

minimum perinatal dataset, they also collect data on hundreds of other items

during the course of a pregnancy. That dataset, however, is not linked to the NPDC.

The feedback from some midwives is that they don't want to be

collecting data twice, but the benefit of the perinatal death data collection

tool is that it is an all-encompassing one-stop shop which incorporates

contributing factors, classifications and categorisations. So they sit parallel

to one another, with equal importance in the arena of stillbirth,...It's a

shame they're not going to talk to one another, because otherwise you could

dump them there to export a lot of the information from midwives.[66]

4.65

The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health (ALSWH), a

longitudinal population-based survey examining the health of over 58 000

Australian women, is funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and

managed by the universities of Newcastle and Queensland. The study includes a

survey of women's experience of stillbirth throughout their reproductive years.

4.66

ALSWH links women's survey data to administrative datasets providing

perinatal data (with provision for participants to opt out), and makes the data

freely available to researchers. It also sources hospital admission and cancer

registry data at the state/territory level and MBS and PBS data at the national

level.[67]

4.67

If made mandatory, linking the different datasets across states and

territories, and integrating them with the perinatal data, PBS data, MBS data,

and Perinatal Data Collections would yield important information including the

financial impact of stillbirth on the public health system.[68]

Improving perinatal reporting and

data collection

4.68

In order to address inconsistencies and delays in perinatal data

reporting, and ensure that timely and consistent data are available to

researchers and policymakers, Stillbirth CRE recommended the following

strategies:

- introduction of a standardised national electronic reporting

system to collect 'real-time' data of all births across Australia, including

agreement on a single definition of stillbirth and the reporting systems to be

used;

-

annual reporting on perinatal deaths nationally, with a focus on

stillbirths and including Indigenous and other high risk groups, to enable the

impact of programs and policies to be monitored for effectiveness;

-

inclusion of stillbirth rates as a key performance indicator in

all state and territory annual perinatal outcomes reports; and

-

hospital level audits of stillbirths and neonatal deaths to

identify factors relating to care, to be included in national, state and

territory reporting that informs improvements in clinical practice.[69]

Perinatal mortality audits

4.69

In its report on perinatal deaths in 2013−14

the AIHW noted that, of the 6037 perinatal deaths that occurred, only 235 cases

were reviewed by a jurisdictional perinatal review committee to consider

possible contributing factors that would assist in identifying systemic issues

affecting the perinatal mortality rate. Of the 235 cases reviewed, 99 were

found to have contributing factors including professional care (58 per

cent) or to the situation of the mother, her family or social situation

(39 per cent), with 38 cases having factors likely to have significantly

contributed to the adverse outcome.[70]

4.70

Several submitters and witnesses called for a national policy on the

conduct of stillbirth autopsies and perinatal mortality reviews as well as the

collection and sharing of data.[71]

4.71

The Clinical Practice Guideline for Care Around Stillbirth and

Neonatal Death, developed by the Perinatal Society of Australia and New

Zealand (PSANZ) and Stillbirth CRE, encourages clinicians in maternity services

to standardise investigation, classification and reporting of stillbirths in

order to improve the quality of data in Australia. However, Stillbirth CRE

noted that application of this Guideline has been variable across Australia.[72]

4.72

Ms Natasha Donnolley, who co-authored the first report on perinatal

deaths in Australia, was critical of the lack of a national approach to

perinatal mortality audits. She noted that, whilst there is now an electronic

data collection tool available to jurisdictions, only Victoria has been active

in this area.[73]

4.73

Victoria has a long tradition of individual case review through the

Consultative Council of Obstetric and Paediatric Mortality and Morbidity, an

independent legislative body charged with reviewing all perinatal, child and

adolescent deaths. Recommendations arising from these reviews are used to

direct improvements in healthcare provision.

4.74

Victoria also undertakes annual reporting of Victorian Perinatal

Services Performance Indicators which compares identifiable hospital data

on outcomes for mothers and newborns against 10 safety and quality indicators. Making

this information publicly available to clinicians and families has resulted in

a 35 per cent improvement in the detection of fetal growth restriction.[74]

4.75

Ms Donnolley noted that there has not been a state-wide audit of

perinatal mortality in NSW, and it is therefore not possible to learn lessons

about causes and prevention of stillbirth.

Other states have recently commenced piloting an electronic

perinatal mortality audit tool but a national approach is urgently needed for

consistency and for maximum benefit. Parents deserve to know that when they

consent to post mortem examinations, that the information is contributing to a

full investigation of their baby’s death and that it will be used to the

benefit of others as well as to find their own answers.[75]

4.76

Several witnesses noted that New South Wales (NSW) public hospitals are

required to prepare a 'root cause analysis' undertaken by a group of

independent expert clinicians external to the hospital where a stillbirth has

occurred. However, this is only undertaken by private hospitals on a voluntary

basis. In addition in NSW, which has almost one-quarter of all

stillbirths in Australia, the perinatal mortality review committee has not

undertaken a perinatal mortality review for more than four years, and its

policy is more than seven years out of date.[76]

4.77

The committee also heard evidence from bereaved parents that there was

no standard information collected from them in relation to their experience of

the pregnancy in the period immediately preceding the stillbirth, and no

clarity as to how information obtained through a review of the stillbirth was

compiled or subsequently used by researchers or clinicians.[77]

4.78

One submitter proposed giving a survey to all parents after their child

is stillborn which, when combined with data from the hospital, could be made

widely available to researchers, medical professionals and families to help

them better understand risks and methods of prevention.

It is not enough for research to be published in obstetric

and midwifery journals. Women may see a whole range of medical professionals

during their pregnancy, and each have a role to play in ensuring the safety of the

woman and her baby.[78]

Successful international models

4.79

Several witnesses commented on the success of overseas models of

stillbirth data reporting and collection, with evidence indicating that they

had contributed to a significant reduction in the rate of stillbirth in those

countries.

4.80

Professor Jason Gardosi, Director of the Perinatal Institute in the UK,

reported on the success of a stillbirth prevention program developed by the

Perinatal Institute using detailed case reviews and analysis of regional

maternity data.

4.81

The GAP program, which has now been implemented in over 80 per cent of

UK hospitals in the National Health Service, is a comprehensive training and

audit program drawing on data collected in relation to the mother's height,

weight, previous pregnancies and ethnicity to produce a core dataset of

maternal characteristics. It also enables the generation of customised

antenatal growth charts (GROW) to assist obstetricians, midwives and

ultrasonographers in undertaking antenatal assessments, and is credited with

reducing stillbirth rates by 23 per cent over the last six years.[79]

4.82

The Perinatal Institute has also been commissioned to roll out the GAP

program in New Zealand, and it has produced an Australian version. The

customised GROW chart and calculators are already being used by clinicians in

some Australian states and territories, with evidence suggesting that they are

helping to improve antenatal identification of babies at risk due to fetal

growth restriction. The Perinatal Institute (UK) concluded that:

...a significant and sustained impact on stillbirth prevention

will require a co-ordinated, intensive yet affordable programme, modelled on

experience elsewhere and adapted to Australian circumstances.[80]

4.83

The MBRRACE-UK program is an initiative established in 2012 and administered

by the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership to conduct surveillance and

investigate causes of maternal deaths, stillbirths and infant deaths. The

program involves confidential enquiries into aspects of perinatal death

including stillbirths, and has a collaborative and multi-jurisdictional

approach. In 2016 the rate of perinatal mortality had decreased overall, and

the stillbirth rate for twins had nearly halved since 2014.[81]

4.84

The Netherlands has implemented a system of timely and consistent data

collection and review, resulting in the rate of stillbirth being reduced by

nearly 60 per cent.

The Netherlands system incorporates about seven different

elements but it incorporates staff education, it incorporates patient

education, it incorporates central recording systems with central reporting and

it requires that to be monitored and for people to be accountable for it. So

the hospitals are accountable for their own process issues, if they notice that

there's something wrong with staffing or this or that. But,

at a higher level, if they notice that a particular part of the Netherlands has

more stillbirths, then they look at it. So there's a local level of

accountability as well. They also have a higher doctor-patient ratio than other

countries. That's been constant over the time, but the progressive improvement

that they've demonstrated is incredible. It's very impressive.[82]

4.85

The mortality review process used in the Netherlands has two steps. The

first is a quick investigation to detect major patient safety or service

issues, often in the form of a root cause analysis. The second step involves a

more formal investigation between four and six weeks after the stillbirth and a

formal perinatal mortality review meeting at which the case is discussed.

Finally, the investigator meets with the bereaved family and outlines the

review outcomes. Parents may also attend the review meeting.[83]

...they took the aeroplane crash approach, which was to look at

the systemic errors all the way along. What they found was that talking to the

family within 48 hours of the loss to specifically identify what the parents'

questions were meant that, when the case was investigated, those questions

could be answered. So the parents were engaged in the process in a way where

every question they asked, whether it was important or not, was given an

answer. These are often given in a written document. The family is then engaged

again at the four-week point. They would speak to the families and do all of

the appropriate bereavement care again at that stage and make sure that they

were utilising the appropriate resources. Again, they would find out what the

family wanted to know et cetera.[84]

4.86

The Netherlands program also provided the basis for a successful

Scottish education program, Maternity Care Quality Improvement Collaborative,

implemented in 2011 and subsequently adopted in the UK (see Chapter 7).[85]

Autopsies and other post-mortem investigations

4.87

As noted above, PSANZ and Stillbirth CRE have developed a Clinical

Practice Guideline to improve maternity and newborn care for bereaved parents

and families, and to improve the quality of data on causes of stillbirth and

neonatal deaths through appropriate investigation, including autopsy, audit and

classification.[86]

4.88

The Guideline recommends that all parents be offered the option of a

high quality autopsy following stillbirth or neonatal death. Stillbirth CRE

considers autopsy to be the 'gold standard investigation' for perinatal deaths

and should be offered to parents by trained health care professional.[87]

4.89

The Guideline also recommends that, in the case of a stillbirth,

neonatal death or birth of a high risk infant, the placenta, membranes and cord

should be sent for examination by a perinatal/paediatric pathologist regardless

of whether consent for an autopsy has been granted.[88]

Low autopsy rates

4.90

Autopsy rates for perinatal death are low in Australia, despite advocacy

over a long period for more autopsies to be performed and particularly where a

cause of stillbirth has not been identified.[89]

4.91

Autopsy is not a mandatory reporting item in state and territory

perinatal data collections, and performance of an autopsy is not obligatory for

stillbirths unless the death is referred to a coroner. The rates of autopsy

therefore vary considerably across the states and territories, from 31 per cent

in Queensland to 62 per cent in WA. The autopsy rates are even lower for Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander stillbirths.[90]

4.92

In 2011−12,

for example, autopsies were conducted in 42.3 per cent of stillbirths in

Victoria, Queensland, WA, SA, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory.[91]

4.93

According to Stillbirth CRE, autopsy rates are higher and unexplained

stillbirth rates are lower in WA and SA, which may be explained by the

existence of coordinated perinatal services in those jurisdictions.[92]

4.94

Whilst the Clinical Practice Guideline has been in place for more than

10 years, it is not mandated.[93]

Between 2004 and 2008 the number of unexplained antepartum deaths was 1949, but

autopsies were undertaken for less than half of these (47 per cent). In

addition, whilst 40 per cent of babies may have some type of post-mortem

examination, only 20 per cent are given a full autopsy.[94]

4.95

The AIHW reported that in 2013-14 full autopsies were performed in only

21 per cent of stillbirth cases in Australia compared to the UK (43.5 per cent)

and New Zealand (42.5 per cent).[95]

4.96

Research into the low rates of autopsy in perinatal death cases suggests

that contributing factors include lengthy delays in finalising an autopsy, and

poor counselling of parents about the option of having an autopsy performed.[96]

Mr Haldane reported, for example, that he and his partner were told that a full

autopsy report may take 18 months to be completed.[97]

4.97

The length of time taken to complete an autopsy varies from state to

state. In Victoria, the Victorian Perinatal Autopsy Service (VPAS) completes

perinatal autopsies within eight weeks, as Associate Professor Kerryn Ireland-Jenkin,

Head of Unit at VPAS, explained:

Within two business days of a perinatal autopsy being done,

there should be what's called a preliminary report that goes back. The

preliminary report doesn't really provide a lot of pathology data, but it

basically says—this is important, because we have a service where people are

referring to three hospitals in Victoria: 'Your baby came to hospital X. An

autopsy was performed by Dr Y on this date. This is the list of investigations

that we performed in that autopsy. We will be issuing a final report within

eight weeks.' That fits with the requirement by NPAAC guidelines around autopsy

turnaround time. Why do we say eight weeks? Could we turn them around a little

quicker? It's often the ancillary investigations that take almost up to the

eight weeks—maybe the genetics, sometimes radiology et cetera. We feel that, if

we list that turnaround time, that's something that we think is absolutely

achievable, and we'd rather say something that's realistic and fits within

national guidelines than pretend we're offering something that is better than

we can actually offer, and then people are disappointed and make appointments

without data being available.[98]

4.98

In contrast, in NSW, an autopsy report can take more than 12 months to

be completed, forcing parents to wait for the information that may help them to

avoid a future stillbirth or other pregnancy complications.[99]

Queensland has been up to 18 months behind in its reporting, due to a lack of

resources and funding.[100]

4.99

Stillbirth CRE noted that lengthy waiting times and uncertainty around

timeframes for the results of autopsies and other investigations are a source

of distress for many bereaved parents.[101]

4.100

Dr Adrienne Gordon, Neonatal and Perinatal Medicine Specialist, Royal

Australasian College of Physicians (RACP), noted that there are less invasive

options available to families who do not wish to have a full autopsy conducted

on their baby.

You can have a post-mortem MRI scan and you can request just

an external examination of the baby by a skilled perinatal pathologist.

Obviously, the placenta is key, so it's very important that, if a family do

decline to have further examination with an autopsy, the placenta is still

looked at. I do think there are other options.[102]

4.101

Professor Jane Dahlstrom stated that examination of the placenta is an

important part of stillbirth investigation and influences the quality of the

data available. Professor Dahlstrom also considered that such investigations

should be undertaken by specialist perinatal pathologists, noting that: 'perinatal/placental

pathologists are more likely to detect significant disease in a placenta

associated with stillbirth than a general anatomical pathologist'.[103]

Associate Professor Ireland-Jenkin simply stated:

There are some of us who work in this area who feel that, if

we—this is pathologists—were only allowed to do one test in the investigation

of stillbirth and if you said to me, 'Would you like to examine the placenta or

would you like to perform the autopsy?' I think I would choose the placental

pathology, because I think it's incredibly important.[104]

4.102

There is, however, a lack of funding to undertake stillborn autopsies in

some jurisdictions, and this is compounded by a shortage of skilled

pathologists available to undertake autopsies on stillborn babies—an issue for high-income

countries more generally.[105]

4.103

Dr Gordon noted that, in NSW where the autopsy rate is relatively low,

the government has introduced a statewide perinatal pathology service that is

available to all families, regardless of their geographical location. The

service includes a coordinator and a central telephone number: 'It's all quite

new. But I guess one solution to limited numbers of people is having some

investment from the jurisdiction and a statewide service'.[106]

4.104

Similarly, the Victorian government has introduced a coordinated perinatal

autopsy service in public hospitals.[107]

The VPAS stated that the perinatal autopsy rate in Victoria is approximately 40

per cent, although it considered the optimal rate to be 60 per cent, and considered

that a centralised service was essential to achieving consistency in stillbirth

reporting and improvements in a hospital's procedures.

The value of a high quality, centralised perinatal

post-mortem service is that it provides high quality, consistent data regarding

the findings (report) in a case of perinatal death...A high quality perinatal

autopsy service reduces the rate at which cases of stillbirth are classified as

Unexplained, which is an important outcome.[108]

Autopsy costs and access

4.105

The committee heard that, since there is no funding available under the MBS

to undertake a stillbirth autopsy, the costs must be met by state/territory

health departments, hospitals or families.[109]

4.106

Associate Professor Ireland-Jenkin advised that the rebate levels for

autopsy in Victoria are set by, and the costs allocated to, the state

Department of Health and Human Services. She also explained:

There's no uniform rate of reimbursement across Australia. In

some healthcare jurisdictions, the number that's been quoted to me—and I don't

know the precise details—may be significantly higher than the current rates

that are set in Victoria. We did engage in creating a business case when the

service was set up at the start of 2016, when we looked at the number of hours

of pathologist time, registrar time et cetera. We did a really robust business

case.[110]

4.107

Other witnesses suggested that the cost of a perinatal autopsy is

between $3000 and $5000, but Professor Flenady explained that '[m]ost parents,

obviously, aren't charged. Even in the private system it will be absorbed.'[111]

Dr Diane Payton, Chair, Paediatric Advisory Committee, Royal College of Pathologists

of Australasia (RCPA) also discussed costs associated with transporting a baby

from a regional or remote location to a major metropolitan hospital so that an

autopsy can be performed.[112]

4.108

Research in other high-income countries identified similar problems,

with resources being diverted away from stillbirth investigations.

Failure to offer autopsy denies parents a chance to

understand the cause of their baby’s death, increases the proportion of

unexplained stillbirths, and hinders the effectiveness of subsequent audits. A

crucial shortage of perinatal pathologists also hampers efforts. Such a

shortage was shown in our surveys, where only 26% of care providers reported

that autopsies were undertaken or supervised by perinatal or paediatric

pathologists. Resources continue to be diverted away from perinatal pathology

services, despite stillbirths and neonatal deaths outnumbering all deaths from

cancer.[113]

4.109

Mrs Iverach stated that the available data for research is limited

because families are not being given sufficient support following a stillbirth,

resulting in the investigations of their baby's death not being completed.

The specialist reported to me that deaths are often listed as

“cord accident” and this does not give an accurate cause or indication of

factors involved...making this conclusion unhelpful in prevention or change. The

specialist stated that “cord accident” is often used when no other data is

available to make a full determination and this is the best conclusion they can

make.[114]

4.110

Dr Warland recommended supplementing clinical data collection by

introducing a standardised verbal autopsy from parents as soon as possible

after the stillbirth.

This verbal autopsy should include questions about whether or

not the mother noticed changes in her body and/or her unborn baby’s behaviour

in the days leading up to the stillbirth, what she did or didn’t do about it

and also what her maternity care provider did, or didn’t do, about it.[115]

Coronial investigations

4.111

Traditionally, Australian coroners have jurisdiction to investigate the death

'of persons who at some stage have been alive after they have been born'.[116]

The committee heard evidence from several witnesses about the merits of

extending coronial jurisdiction to cases of stillbirth.

4.112

Dr Warland noted that babies are not legal entities until they are born

live, and therefore stillbirths fall outside of the jurisdiction of coroners.

She argued that this is an anomaly that should be corrected, so that there is

greater accountability for stillbirth deaths.[117]

4.113

Some researchers have argued that coronial inquests are not the most

appropriate way of investigating stillbirths, and that autopsy and/or clinical

audits would be preferred options, with the responsible health care service

undertaking the audit, which would be reviewed by an independent external

panel.[118]

4.114

The UK is currently considering widening its coronial jurisdiction to

include certain cases of stillbirth, which is currently excluded on the basis

that there has to have been an independent life prior to coronial

investigation.[119]

4.115

In Australia, coroners do not investigate stillbirth, as 'a coroner has

jurisdiction not in respect of injuries or stillbirths but in respect of the

deaths of persons who at some stage have been alive after they have been born'.[120]

4.116

Mrs Dimitra Dubrow, Principal and Head of Medical Negligence, Maurice

Blackburn Lawyers, noted that coronial findings often drive reforms in

policies, procedures and standards, including increased awareness and

management of risks, the need for ongoing training for locum obstetricians and

a review of hospital procedures. She also noted that autopsy reports often

contain statements that are unhelpful and arbitrary, and that a coronial

investigation might yield significant new information about the circumstances

of stillbirth. She argued that a similar reform in Australia would ensure a

greater degree of independence, accountability and transparency in the process

of determining why unexpected stillbirths occur. She noted that a coronial

investigation should be used to determine the cause of stillbirth, rather than

being a 'fault-finding exercise'.[121]

4.117

Dr Carrington Shepherd, Co-Lead, Western Australian Perinatal

Epidemiology Group, considered that there is a need for a more systematic and

independent approach to port-mortem investigations of stillbirths. He proposed

that the National Coronial Information System, that includes information on

perinatal loss, could be expanded to include stillbirth and autopsy findings.[122]

4.118

Mrs Claire Foord, Chief Executive Officer and Founder of Still Aware, noted

that there is generally a gap in autopsy reports where no cause of death could

be determined, and called for the use of a coronial investigation in such cases

to ensure that all the available evidence from both clinical and family

perspectives is recorded and reviewed. Such an investigation would contribute

to a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding the stillbirth.

There are gaping holes in autopsy reports that say 'there was

no reason for anything to go wrong' or 'we have no understanding of any

precursor to this'. But the fact is they're not going to know that unless they

can go back and look at historical records and talk to all of the people

involved in this child's life, and that's parents included. So, we're asking

for the coroner to have jurisdiction not over every childhood death to

stillbirth but rather those that are preventable deaths in the third trimester

that can be reported, and as such it would be said, 'Okay the coroner should

have jurisdiction over this.'[123]

4.119

The National Perinatal Mortality Data Reporting Project noted that a

requirement for a coronial investigation can delay jurisdictions submitting

registration data to the ABS for inclusion in the national perinatal data

collections.[124]

Committee view

4.120

The lack of a consistent and coordinated approach to stillbirth at a

national policy level has contributed to a fragmentation of stillbirth

reporting and data collection, and is inhibiting efforts to undertake research

that will assist in reducing the incidence of stillbirth in Australia.

4.121

The committee heard evidence from leading stillbirth research

organisations that current national practice for stillbirth data collection in

Australia is 'suboptimal', and is significantly impacting on their ability to

answer important questions about the causes and prevention of stillbirth.

Contributing factors include duplication of effort and disparate approaches

across and within states and territories; fragmented data collections that do

not link maternal health, pregnancy and birth risk factors; and a system that

is fraught with delay and unresponsive to change.

4.122

The lack of progress in reducing stillbirth rates in Australia

highlights the urgent need for a multi-jurisdictional commitment to systematic

stillbirth reporting and data collection. This is crucial if governments are to

provide researchers with reliable, timely and consistent data at a granular

level necessary for the development of targeted, evidence-based prevention

strategies.

4.123

The committee acknowledges the Australian government's proposed data

sharing and release legislation that aims to enhance the integrity of the

public sector data system and make it more accessible to researchers.[125]

It urges the government to take into consideration, as part of its

consultation, the need for Australian stillbirth researchers to have access to a

NPMDC that is high-quality, timely, consistent, detailed, and cost-effective to

access. It notes that the Vital Statistics Online Data Portal in the USA offers

a best practice model that, if adopted in Australia, would ensure that

stillbirth researchers are no longer hampered in their efforts to reduce the

unacceptably high rate of stillbirth in Australia.

4.124

The committee also acknowledges the importance of the current PHRN-led

project, being undertaken as part of the National Collaborative Research

Strategy, which aims to improve linkages between state/territory data

collections and the national data collections through the AIHW.

4.125

Whilst such initiatives are welcome, the paucity of timely, high-quality

data on stillbirth remains a significant impediment to determining national

research priorities, addressing substandard care, identifying causes and risk

factors, and establishing evidence-based prevention strategies.

Recommendation 2

4.126

The committee recommends that the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory

Council agrees to prioritise the development of a comprehensive, standardised,

national perinatal mortality data collection that:

- includes information on timing and cause of death, autopsy and

termination of pregnancy; and

-

links to the National Death Index and perinatal mortality data

collections to utilise information on maternal health, pregnancy and birth risk

factors.

4.127

The committee urges the AHMAC to consider endorsing the strategies

proposed by the Stillbirth CRE, as follows:

- adopting a single national definition for stillbirth to be used

by all jurisdictions;

-

implementing a standardised national electronic reporting system

to collect 'real-time' data on births and deaths, including identification of Aboriginal

and Torres Strait Islander and other high risk groups;

-

including stillbirth rates as key performance indicators in

annual perinatal outcomes reports; and

-

undertaking hospital level audits to identify contributing

factors relating to care in relation to stillbirths and neonatal deaths.

4.128

Determining the cause of a baby's death is one of the most significant questions

surrounding stillbirth, and the lessons learned from reviews of medical data

are important for improving research and education as well as clinical

practice. Successful international programs such as MBRRACE-UK offer valuable

models for a more collaborative, multi-jurisdictional approach to perinatal

mortality review programs. However, the committee heard that the number of

perinatal mortality audits in Australia is low and represents a significant

barrier to reducing the rate of stillbirths in Australia.

4.129

The committee notes that there is no funding available under the MBS to

undertake a stillbirth autopsy, and that the costs must be borne by

state/territory health departments, hospitals or families. According to state

and territory agencies responsible for data collection, it can take several

years to implement a new mandatory reporting item.

4.130

The lack of funding is contributing to delays in the results being made

available to bereaved parents as well as to researchers. In addition, the

current process for extending MBS funding requires review in order make it

sufficiently flexible to accommodate breakthroughs in medical research and

technology (see, for example, the discussion on genetic testing in Chapter 5).

Recommendation 3

4.131

The committee recommends that the Australian government seeks advice

from the Medical Services Advisory Committee on the economic costs and benefits

of adding stillbirth autopsies as a new item in the Medicare Benefits Schedule,

and urges the government to consider funding the projected cost of this new

item in the 2019−20

Federal Budget.

4.132

The committee acknowledges that Australia has a critical shortage of

perinatal pathologists, severely restricting the number of autopsies and other

pathology services being conducted following stillbirth. Unless more resources

are provided for training and employing perinatal pathologists, efforts to

reduce the rate of stillbirth will continue to be hampered by insufficient

information and data about the causes of stillbirth. This shortage of skilled

perinatal pathologists has significant implications for bereaved parents,

clinicians, health professionals and researchers seeking to understand and

address the causes of stillbirth.

Recommendation 4

4.133

The committee recommends that the Australian government consults with

the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia and relevant education and

training authorities to identify strategies for increasing the number of

perinatal pathologists available to undertake stillbirth investigations in

Australia, including identifying costs and sources of funding.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page