6.1

The cutback in bank branches was foreseen. The Wallis report anticipated

that the banks would rationalise their branch network. In 1997, it concluded:

The Inquiry recognises that there will be a need to replace any

rural bank branches which are closed with alternative delivery channels. If

this occurs, the importance of a branch presence is likely to become less

relevant to individual consumers, if not to the community. As well as ATMs,

EFTPOS, telephone and computer banking, new delivery mechanisms which may be of

assistance in rural areas include mobile rural industry specialists and agency

arrangements with non-financial services providers such as Australia Post.

Rural and remote communities and institutions should work together to explore

alternative delivery options which meet the needs of all concerned.[1]

6.2

Clearly, the Wallis report presumed that while competition would result

in branch closures a range of services would spring up to replace them. As

expected there has been a decline in traditional bank branches accompanied by a

corresponding growth in alternative forms of banking. Taking a broad approach,

this chapter presents an overview of the range and type of banking and financial

services that are now available to people in regional, rural and remote Australia.

Current access to a banking service—overview

6.3

In essence, the banks readily acknowledge that there has been a

reduction across the board of bank branches in Australia. Nonetheless,

according to the ABA, the introduction of different forms of banking, in most

cases, has compensated for the loss. It asserted that the major banks maintain

extensive face-to-face and electronic self-service banking networks throughout

rural and regional Australia.[2]

The ABA submitted that in 2001:

- banks maintained 4,712 branches and around 5,043 agencies;

- Australia Post had 2,821 giroPost outlets (which commenced in

1995); and

- taken together (branches, agencies, and giroPost), the current level

of over-the-counter services available in Australia today is only 14 per cent

less than the number of over-the-counter facilities provided in 1990.[3]

6.4

Mr Bell, ABA, explained further that there are 400,000 EFTPOS outlets in

Australia and 12,000 or 14,000 ATMs together with telephone banking.[4]

There is also the ability for customers in rural and remote areas to deal with

mobile bankers or with regional banking centres on particular agribusiness

matters.[5]

The figures seem impressive and are supported by current data.

6.5

Indeed, the ABA relies on a recent study to demonstrate that the great

majority of Australians have access to a banking service. It maintained that

this latest research shows that there is good representation of financial

services in regional and rural Australia, compared with other commercial and

government services.[6]

The study found that there are a total of 3,380 points of presence for

Australian banking and financial services.[7]

Any Australian non-metropolitan town or metropolitan suburb that contained at

least one banking service (Bank and Credit Union branches, ATMs, giroPost

outlets and Australia Post Office Manual Bank Agency Locations) was considered

as one point of presence for this analysis.[8]

6.6

Before looking at the findings of this survey, the report discusses the

APRA database on access to banking services in Australia on which this survey

was based.

Statistics on access to banking services

6.7

In 1999, the Hawker Report concluded that ‘the statistical information

that is readily and officially available is of limited use in compiling a

picture of the delivery of financial services through branches and agencies.’

It recommended that the Minister for Regional Services, Territories and Local

Government and the Minister for Financial Services and Regulation, in

consultation with State colleagues, undertake a collection of comprehensive

data on the access communities have to financial services.[9]

6.8

In its response to the recommendation, the Government agreed with the

finding that the lack of comprehensive data on the availability of services to

different regions made it difficult to draw conclusions about access to

services in regional and remote areas of Australia and whether they had

improved. It explained that the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority

(APRA) with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and the Reserve Bank of

Australia (RBA) had embarked on a major exercise to review and harmonise its

data collection and analysis processes.[10]

It recommended that:

APRA take into account the recommendations of, and the issues

raised by, the Hawker Committee in its review of data collection and that it

works closely with representatives of the financial sector in determining the

most appropriate data to be collected. The Government also recommends that APRA

consider publishing information that easily and accurately represents the level

of access Australians have to basic financial transaction services both

face-to-face and electronic, and that this data distinguishes between the

access people have in urban and rural communities. The relevant financial

institutions are understood to regard APRA as the most appropriate agency to

handle the collection of such data.[11]

The Commonwealth considers it appropriate to await the outcome

of APRA’s review before it undertakes any separate collection of data on the

access communities have to financial services. If such a collection of data is

to be undertaken by the Commonwealth, then it will be done in consultation with

the relevant State authorities. [12]

6.9

Although APRA did not see the collection and analysis of data on the

availability of banking services as part of its prudential functions, it has

now assumed responsibility for gathering such information. APRA explained that

rather than focus on branches and agencies as was the case previously it had

developed a survey that captures all service channels available to customers. [13]

APRA’s ‘Points of Presence’ database

6.10

In June 2001, APRA announced the release of the Points of Presence data

which was to be the first of an annual series that would over time show the

changing patterns of financial services available to the community. The

information contained in the survey reaches down to the level of individual

service channels within separate localities, towns and suburbs.[14]

The survey recognises that banking services are now delivered through a wide

range of ‘service channels’ and not just by traditional bank branches.

6.11

In its spreadsheet entitled Points of Presence 2001, APRA divides

the various channels of banking service into those that qualify as ‘branches’

and those that do not. To qualify as a ‘branch’, a service channel must meet

the following criteria:

- accepts cash and other

deposits (including business deposits) and provides change;

- facilitates the keeping of accounts

for customer access, including the provision of account balances;

- opens and closes accounts;

- can facilitate or arrange the

assessment of the credit risk of existing and potential customers; and

- offers additional services in

the one establishment such as financial services, business banking and

specialist lending.

Problems with definitions—branch and agency

6.12

Although the definition of a branch is now used consistently in the

database, institutions have the latitude to name and define their other service

channels as they choose. According to APRA, this approach makes comparing

similar service channels across institutions difficult. Indeed, APRA’s figures

provide almost 120 different types of ‘points of presence’ (see appendix 4).

The sheer number of terms employed under the category ‘non branch’ is confusing

especially where a number of institutions retain the term ‘branch’ in titles

even though the facilities are not branches under the definition. These include

terms such as Branch–Kiosk; Branch–Non Cash, Interstate Branches and Mini

Branch. While the description accompanying each point of access conveys some

understanding of the level of service provided, the range is still very great

and the information is buried in the raw data. For instance the term ‘agency’

is used in both branch and non branch categories—for example, Commonwealth

manual agencies and agencies with Electronic Funds Transfer at Point-of-Bank

(EFTPOB) are not regarded as a branch while the National’s agencies are deemed

to be branches.

6.13

Thus, the definitions present a very difficult challenge for statistical

analysis. How does one compare a Westpac In-Store bank with an Elders Rural

Bank agency? An Agribusiness Banking Centre with a MAXI Multimedia kiosk?

Measuring banking services according to the number and location of ‘points of

presence’ without further considering the services those points of presence

actually deliver is fraught with difficulty. Terms such as ‘agency’ are too

broad to have any value as a statistical tool to help in understanding the

level of service provided.

6.14

Other information about the quality of service is also missing. For

example, the Committee visited the small Queensland town of Blackbutt which has

an RTC. The statistics may well show that this town has a banking facility but

it does not show that the Nanango Shire Council subsidises this facility to the

amount of between $8,000 and $10,000 a year.[15]

Goombungee may well have an ATM but according to a council representative it

spends 90 per cent of its time with ‘an out of order’ sign on it.[16]

6.15

More importantly, while the data shows the services available it

provides no indication of areas without banking facilities. This deficiency in

the data base was evident to the Committee when it sought information on the

availability of banking services to remote communities in the Northern

Territory. The only information available was a very basic survey undertaken

by field officers (see appendix 5). The Committee believes that any data

collected on the availability of banking services in Australia should also

document communities where there is no point of banking presence.

Other difficulties in analysing the data

6.16

APRA also drew attention to another aspect of the data that makes

analysis difficult. It warned that service channels other than those meeting

the definition of a branch, can not be aggregated to achieve the total. The

same points of presence may be simultaneously reported by separate

institutions, for example giroPost.

6.17

Furthermore, APRA told the Committee that it did not believe that the

2002 comparison figures for 2001 are worth anything mainly because the

institutions provided numbers but ‘did not know where to classify them’.[17]

The Committee hopes that these teething problems are soon resolved.

6.18

Without doubt the Points of Presence database is comprehensive—it lists

all facilities providing a banking service. The Committee accepts that the

quality of the statistics now being collected has improved, particularly in

having the one standard definition of a bank branch. Even though the statistics

in defining a branch offer a better understanding of the services provided by

such a facility, the almost 100 remaining types of facilities that are grouped

together under the classification of non branch pose a problem for analysts.

Lack of analysis

6.19

Of greater concern, however, is the lack of analysis of this material.

The Department of Family and Community Services noted that evaluation of the

data is left to individual users. It suggested that there may be some benefit

in APRA or another agency developing ‘a more coordinated approach to analysis’

that could be used by governments, banking and other financial institutions.[18]

APRA, however, told the Committee:

...we do not attempt to analyse or interpret this information, nor

do we have any particular insight into the accessibility of banking services

across regional and rural Australia.[19]

Further that:

...we do not actually want to put the effort into analysing that

return because it is not germane to our mandate which is set out in the APRA

Act.[20]

6.20

The Committee accepts that APRA’s core responsibility is to ensure the

prudential soundness of ADIs. Nonetheless, the Committee believes that the data

collected by APRA is a rich source of information for the banking industry and

for governments and should be presented in such a way that it provides some

insight into the accessibility and level of banking and financial services in

country areas. It definitely should identify areas that have limited access to

bank services particularly those without a bank branch that are dependent on

self-service banking channels.

6.21

The Committee believes that further work is required to refine the

definitions used in this database so they can be used to convey a more accurate

understanding of the level of banking and financial services available across Australia.

The Committee also believes that the body of raw data collected by APRA should

be analysed and presented so that it ‘easily and accurately represents the

level of access Australians have to basic financial transaction services’ in

metropolitan and in country areas. The Government recommended as much in its

response to the Hawker Report.

Recommendation 4

The Committee recommends that the Department of the Treasury and

the Department of Transport and Regional Services review the ‘points of

presence’ database to determine whether the current system of gathering

statistics on access to banking services is producing a full and accurate

representation of the delivery of such services to rural, regional and remote

Australia. Further, acknowledging that APRA does not attempt to analyse or

interpret the information it gathers for the points of presence database, the

Committee recommends that the Australian Government nominate another agency

better suited to carry out such analysis.

6.22

The following section looks at a recent study that draws on APRA’s

database to reach conclusions on the access to banking and financial services

in regional Australia.

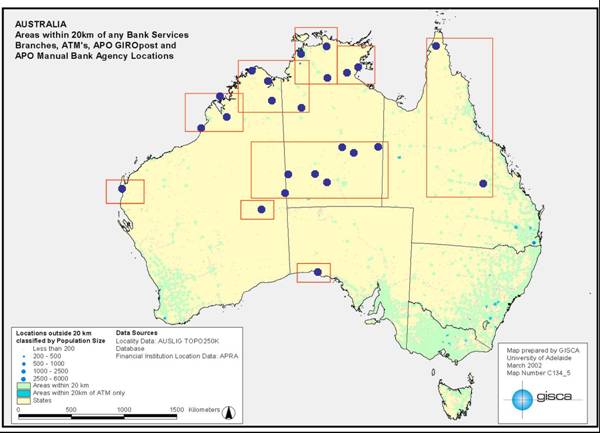

A map of the distribution of banking and financial services in Australia

6.23

On behalf of the ABA, the National Centre for Social Applications of

GIS, the University of Adelaide, conducted preliminary analysis to map the

nation’s access to banking services using the data collected by APRA in its

2001 survey on the various points of presence. It explained its findings as

follows:

For this analysis 20 km was identified as a maximum reasonable

distance to travel to access a banking service. Few localities with a

population greater than 200 persons are further than 20 km from a banking

service. Within the whole of Australia these localities number 32. Within

Remote and Very Remote Australia there are 28 localities that are further than

20 km from a banking service, the majority of these are concentrated within the

Northern Territory and Western Australia, where population densities are low

and distances between populated localities are high...Euclidean analysis of the

distances between those 28 localities and their nearest banking service shows

that 6 are within 50 km, 4 are within 100 km, and 18 are greater than 100 km

from any banking service.

The 28 Remote and Very Remote localities isolated from banking

services tend to be remote communities, whose populations fall between 200 and

950 persons.[21]

6.24

The study also suggested that throughout Australia there are less than

five localities with greater than 200 and less than 700 persons whose only

access to a banking service within 20 km was an ATM.[22]

It concluded that ‘Australians have extensive access to banking services

through a variety of distribution channels—including over the counter, in a

supermarket, newsagent, post office or an ATM’.[23]

6.25

The map below shows the locations of communities in Australia with more

than 200 people that do not have an over-the-counter banking service within 20

kilometres.

Table 6.1—Map showing the

areas within 20 km of any Bank Services Branches

6.26

These statistics appear quite promising for the case that access to

banking services in rural and regional Australia are adequate. For example the

Commonwealth Bank cited APRA’s latest points of presence data to confirm that

it is increasing its services to regional, rural and remote communities through

a variety of distribution points such as ATMs, EFTPOS machines, Woolworths Ezy

Banking and giroPost.[24]

6.27

Unfortunately, definitional problems cloud the issue. As noted earlier

in this chapter, the ABA includes Australia Post Manual Banking Agency

locations and giroPost outlets as banking ‘points of presence’. There are 805

of these agencies and more than 14,000 giroPost outlets throughout Australia,

many in rural and regional Australia. These outlets do not meet APRA’s minimum

criteria for a branch and the level of banking service offered by the manual

banking agency is very limited.[25]

Further still, including an ATM as a banking point of presence means that the

understanding of a banking service is reduced to its most rudimentary level.

6.28

So, while the ABA’s statistics indicate that very few Australians are

more than 20 km from some form of banking service, it is impossible from their

research to determine how many Australians have access to adequate services.

6.29

Thus, although the statistics may seem impressive in showing that there

are only 32 localities in Australia with populations over 200 that do not have

a banking service within 20 kms they give no indication of the level of service

provided to those communities. It should also be noted that the survey did not

include communities with less than 200 residents. There are over 1,000 discrete

Indigenous communities alone with populations under 200. Chapter 15 provides

more information on these communities.

Conclusion

6.30

Clearly, the banks are placing a heavy reliance on non-traditional forms

of banking services to convey a positive message that they are indeed catering to

the needs of those in regional Australia. Evidence to this Committee, however,

highlights community dissatisfaction with the level of service they provide.

Chapter 3 quite clearly identified the problems caused by branch closures or

the withdrawal of banking services from country areas. Chapter 5 found that

because of the lack of competition in some areas of regional, rural and remote

Australia the market was tardy in responding to consumer demands. Against this

backdrop of branch closures and weak competition, the following chapters look

more closely at the range of banking services provided to people in regional,

rural and remote Australia and consider the adequacies of such services.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page

Top