Overview of crystal methamphetamine and its use in Australia

2.1

This chapter provides a summary of crystal methamphetamine and its use

in Australia. It first defines crystal methamphetamine and how it differs from

other methamphetamine substances; it then explores the following matters:

-

Crystal methamphetamine use in Australia, the number of users and

the difficulty estimating the quantity of crystal methamphetamine consumed each

year.

-

Problematic versus non-problematic use and the identification of groups

at risk of developing problematic consumption behaviours.

-

The mental and physical effects of crystal methamphetamine,

specifically methamphetamine-induced psychosis and violent behaviours demonstrated

by some users.

-

Drivers of crystal methamphetamine use and factors that contribute

to problematic use.

-

Price, purity and methods of administration.

-

Poly-drug use as a feature of crystal methamphetamine use and how

this influences users' health outcomes.

-

National data on illicit drug arrests and illicit drug offences

recorded in the criminal courts of each state and territory.

What is crystal methamphetamine?

2.2

Crystal methamphetamine is a form of methamphetamine,[1]

grouped under the class of amphetamine-type stimulants (ATS). The term

'crystal' refers to its crystalline structure, which gives the substance the

appearance of crushed ice,[2]

hence its colloquial name of 'ice'.

2.3

Various common or street names for methamphetamines with reference to

their forms and methods of administration are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: common names for methamphetamines[3]

| Drug type |

Common names |

Forms |

Method of

administration |

| Methamphetamine |

Meth, speed, whiz, fast,

uppers, goey, louee, Lou Reed, rabbit, tail, pep pills.

In paste form it can be

referred to as base, pure or wax.

In liquid form it can be

referred to as ox blood, leopard's blood, red speed or liquid red. |

White, yellow or brown

powder, paste, tablets or a red liquid |

Oral, intranasal,

injection, anal. |

| Crystal methamphetamine |

Ice, dmeth, glass,

crystal, batu, shabu (in South-East Asia) |

Crystalline |

Smoking, intranasal,

injection |

2.4

Some evidence presented in this report refers to crystal methamphetamine

specifically, while other evidence describes methamphetamine and/or amphetamine.

Generally, methamphetamine is referred to when specific data on crystal

methamphetamine is not available. Australia's federal law enforcement agencies

refer to methamphetamine as methylamphetamine.

2.5

During the course of the inquiry, many witnesses rejected the term 'ice'

on the basis this term can have positive connotations and potentially encourage

use. For this reason, this report refers to crystal methamphetamine,

methamphetamine or amphetamine, as appropriate, unless directly quoting

evidence where another name for the drug was used.

Crystal methamphetamine use in Australia

2.6

Accurately ascertaining crystal methamphetamine use in Australia is

difficult, as it is for all illicit substances, due to a paucity of data and

limitations on the accuracy of the data that is available. Despite this,

Australia has a number of initiatives and longitudinal studies that provide

authorities and those working in the alcohol and other drug (AOD) sector with some

insight into the consumption of illicit substances. These include:

-

the National Drug Strategy Household Survey (household survey);

-

the Drug Use Monitoring in Australia (DUMA) program;

-

the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS);

-

Clients of Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Service (AODTS); and

-

the recently established National Wastewater Drug Monitoring

Program.

2.7

These initiatives are discussed in detail below.

National Drug Strategy Household

Survey

2.8

Every three years the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW)

conducts the household survey and reports on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug

use in Australia. The survey includes data on people's attitudes and

perceptions about alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use. The survey allows the AIHW

to collect data from nearly 24 000 people[4]

across Australia, mostly aged 14 years or older.[5]

Key findings from the 2016 National

Drug Strategy Household Survey[6]

2.9

The 2016 household survey showed a decline in recent self-declared use

(defined as use of an illicit drug in the last twelve months) of

meth/amphetamine from 2.1 per cent in 2013 to 1.4 per cent in 2016. Data

from the household survey indicates that the percentage of people using

meth/amphetamine has continued to decline since 2001 (see Table 2).

Table 2: Meth/amphetamine drug use,

people aged 14 years or older, 1993 to 2016[7]

| Year |

1993 |

1995 |

1998 |

2001 |

2004 |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016[8] |

| Meth/amphetamine[9]

(per cent) |

2.0 |

2.1 |

3.7 |

3.4 |

3.2 |

2.3 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.4 |

2.10

Despite the overall decline, the 2016 survey demonstrated that crystal

methamphetamine remains the preferred form of meth/amphetamine for users:

57 per cent of recent users reported that crystal methamphetamine is

their main form of meth/amphetamine used in the previous 12 months (an

increase of 7 per cent compared to 2013).[10]

This result continues an upward trend observed since 2010 (see Table 3).

Table 3: Main form of

meth/amphetamine used in last 12 months, people aged 14 years or older, 2007 to

2016[11]

| Drug |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

| Powder/Speed |

51.2 |

50.6 |

28.5 |

20.2 |

| Crystal/ice |

26.7 |

21.7 |

50.4 |

57.3 |

| Base/paste/pure |

12.4 |

11.8 |

7.6 |

1.6 |

| Tablet |

5.1 |

8.2 |

8.0 |

5.6 |

| Prescription

amphetamines |

3.2 |

6.8 |

3.0 |

11.1 |

| Liquid |

1.3 |

0.9 |

0.5 |

n.p |

| Capsules |

NA |

NA |

2.0 |

3.8 |

2.11

The 2016 survey also reported that the frequency of meth/amphetamine

use has increased, in particular for those people using crystal methamphetamine

(see Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4: Frequency of

meth/amphetamine use by recent users aged 14 years or older (all recent

meth/amphetamine users)[12]

| Frequency of use |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

| At least once a week or more |

13.0 |

9.3 |

15.5 |

20.4 |

| About once a month |

23.3 |

15.6 |

16.6 |

10.6 |

| Every few months |

27.9 |

26.3 |

19.8 |

24.7 |

| Once or twice a year |

35.6 |

48.8 |

48.0 |

44.3 |

Table 5: Frequency of

meth/amphetamine use by recent users aged 14 years or older (frequency of

crystal methamphetamine use)[13]

| Frequency of use |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

| At least once a week or more |

23.1 |

12.4 |

25.3 |

31.9 |

| About once a month |

24.3 |

17.5 |

20.2 |

8.3 |

| Every few months |

20.7 |

23.1 |

14.3 |

22.6 |

| Once or twice a year |

31.8 |

47.0 |

40.2 |

37.3 |

Perceptions and attitudes towards

meth/amphetamine

2.12

The household survey also surveys respondents' perceptions and attitudes

towards illicit drugs. Despite the overall decline in use, the perception that

meth/amphetamines are causing social and criminal problems has increased.

2.13

Household survey data shows a significant increase in the number of

people who believe that meth/amphetamines are the most concerning drugs for the

general community and in 2016, for the first time, meth/amphetamines overtook

the excessive consumption of alcohol as the drugs of most concern (see Table 6).

Meth/amphetamines were also considered the drugs most likely to be associated

with a 'drug problem' (21.9 per cent in 2013 to 46.4 per cent in 2016).[14]

Table 6: Drug thought to be of most

concern for the general community, people aged 14 years or older, 2007 to 2016[15]

| Drug |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2016 |

| Excessive drinking of alcohol |

32.3 |

42.1 |

42.5 |

28.4 |

| Cannabis |

5.7 |

4.5 |

3.8 |

2.6 |

| Meth/amphetamine |

16.4 |

9.4 |

16.1 |

39.8 |

| Cocaine |

8.3 |

6.1 |

3.6 |

3.3 |

| Ecstasy |

6.0 |

5.5 |

5.2 |

5.0 |

| Heroin |

10.5 |

11.4 |

10.7 |

7.5 |

2.14

The 2016 household survey noted that factors, such as media coverage and

personal experiences, are likely to influence the opinions of respondents in

terms of perceptions of and attitudes towards illicit drugs.[16]

2.15

The committee heard evidence from Professor Rebecca McKetin in 2015 and

again in 2017. Professor McKetin referenced a detailed study of the household

survey conducted by Professor Anne Roche. This study showed that prevalence of

use was stable but this was not consistent across regions. It found use in

regional areas had increased, whilst it had decreased in metropolitan areas.

Professor McKetin said researchers have followed these indicators and:

...there is certainly a broad range of indicators consistently

showing an increase. There is definitely an increase in the level of

problematic use and there is a little evidence of an increase in the uptake of

use too, but I think it is important to understand that the situation is not

the same everywhere, so you cannot make one sweeping statement that things have

not changed.[17]

2.16

Professor McKetin also explained that the study of the household survey

shows evidence that there has been under-reporting of methamphetamine use,

which she believes may explain for the disparate trends in other indicators and

the survey.[18]

Professor Steve Allsop from the National Drug Research Institute (NDRI) added

that:

We also have to recognise that, for all sorts of reasons, we

end up with underreporting. There is a high nonresponse rate. Many of the

people who might be particularly at risk are more likely to be non-respondents;

for example, people who are in the prison system, people who do not have phones

or addresses that are easily contactable, people who choose not to respond—or

to not respond accurately—or sometimes people do not even know accurately. For

example, if you ask people how much alcohol they have consumed, some people

underreport deliberately and some people do not have a good idea.[19]

2.17

This issue had been raised by Professor McKetin in earlier evidence

provided to the committee:

There is also an issue with population surveys that they

quite strongly underrepresent problematic drug use, and they are very sensitive

to any stigma around drug use. There is negative publicity, and we have seen

this before for methamphetamine; you get strong underreporting. If you look

back to the 2001 survey, almost 10 per cent of Australians said they had ever

used speed, amphetamine and methamphetamine. By 2007, after all of the bad

press, that fell to 6 per cent. Suddenly 4 per cent of Australians who had used

methamphetamine no longer have used methamphetamine. That is the extent of

underreporting that you can get.[20]

2.18

The Department of Health addressed the issue of under-reporting in the

household survey. It acknowledged that having people admit to an illegal

activity may lead to under-reporting, but:

That is the way people answer, and there is nothing you can

do to control that. However, I would point to, if there is underreporting—and I

do not know whether there is—you can still look at the trends in the data. You

would assume that you would be getting the same kind of underreporting or

over-reporting or whatever it might be. The way statisticians work with data is

to work out what the degrees of error are.[21]

Drug Use Monitoring in Australia

program

2.19

The DUMA program measures drug use amongst police detainees from nine

sites across Australia. This ongoing study examines the relationship between

drugs and crime, local drug markets and patterns of use by detainees. DUMA data

is collected and published periodically by the Australian Institute of

Criminology (AIC). Its last publication was on 9 February 2016, as a part of a

series of papers about methamphetamine use and the perspectives of DUMA police

detainees.[22]

The Drug use monitoring in Australia: 2013–14 report on drug use among

police detainees is the last full year analysis publicly available on the

AIC website, but the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission's (ACIC) Illicit

Drug Data Report 2015–16 notes results from the 2014–15 and 2015–16 DUMA

examinations.

2.20

According to the Illicit Drug Data Report 2015–16, the number of

detainees testing positive for amphetamine use increased, from 40.9 per cent in

2014–15 to 50.5 per cent in 2015–16. This recent result marked the

'highest percentage reported in the last decade'.[23]

The ACIC identified the increase in detections of methamphetamine

(methylamphetamine) use in detainees as the reason for the continued upward

trend in detections, with data showing an increase from 38.7 per cent in

2014–15 to 49 per cent in 2015–16. Further:

The proportion of detainees testing positive for

methylamphetamine continues to be higher than the proportion testing positive

for MDMA,[24]

heroin, cocaine, benzodiazepines and opiates (excluding heroin). In 2015–16,

the proportion of detainees testing positive for methylamphetamine was higher

than the proportion testing positive for cannabis (44.4 per cent). In 2015–16,

59.7 per cent of detainees self-reported recent methylamphetamine use, an

increase from the 50.4 per cent reported in 2014–15.[25]

Illicit Drug Reporting System

2.21

Since 1999, the IDRS has monitored illicit drug use across all states

and territories. The IDRS provides a coordinated monitoring system with a

particular focus on heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine and cannabis. The IDRS comprises

interviews with people who inject drugs, interviews with experts, and the

examination of other data sources, such as opioid overdose data, treatment

data, and purity of seizures of illicit drugs made by law enforcement agencies.[26]

2.22

Key findings from the IDRS for 2016 showed:

-

75 per cent of the national sample reported 'using one or more

forms of methamphetamine in the last six months on a median of 36.5 days',

significantly higher than the 2015 median of 24 days;[27]

-

recent use of crystal methamphetamine was significantly higher,

with use increasing from 67 per cent in 2015 to 73 per cent in 2016;

-

the frequency of use in the last six months for crystal

methamphetamine had increased from 20 days in 2015 to 30 days in 2016 in total;

and

-

the majority of methamphetamine users administered the drug

through injections; and this method was common to all forms of methamphetamine

(see Table 7).[28]

Table 7: Proportion of people who

inject drugs that reported use of crystal methamphetamine in the preceding six

months, by jurisdiction, 2010–2016[29]

| % |

National |

NSW |

ACT |

Vic. |

Tas. |

SA |

WA |

NT |

Qld. |

| 2010 |

39 |

48 |

48 |

36 |

20 |

60 |

40 |

18 |

37 |

| 2011 |

45 |

53 |

57 |

53 |

26 |

44 |

46 |

28 |

50 |

| 2012 |

54 |

68 |

66 |

59 |

43 |

56 |

64 |

26 |

44 |

| 2013 |

55 |

74 |

61 |

55 |

45 |

57 |

59 |

30 |

50 |

| 2014 |

61 |

74 |

72 |

75 |

54 |

60 |

53 |

26 |

58 |

| 2015 |

67 |

65 |

79 |

71 |

59 |

70 |

64 |

60 |

62 |

| 2016 |

73 |

77 |

78 |

73 |

73 |

75 |

62 |

69 |

69 |

Clients of Alcohol and Other Drug

Treatment Services

2.23

The AIHW collects data as part of the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment

Services National Minimum Data Set (AODTS NMDS). Data included in the AODTS

NMDS is from treatment provided by publicly-funded AOD treatment agencies in

Australia. Since 2003–04, the AIHW releases the Clients of AODTS reports.[30]

2.24

The Clients of AODTS report for 2015–16 found that 23 per cent of

closed treatment episodes[31]

had amphetamines listed as the principal or additional drug of concern.[32]

There were 46 441 treatment episodes for amphetamines in 2015–16, an increase[33]

from 32 407 treatment episodes in 2014–15 (see Table 8).[34]

Table 8: National closed treatment

episodes for clients own drug use by principal drug of concern, 2010–2016[35]

| Year |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

| Amphetamine |

12 563 |

16 875 |

22 265 |

28 919 |

32 407 |

46 441 |

National Wastewater Drug Monitoring

Program

2.25

On 26 March 2017, the ACIC released its first report from the National

Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program (wastewater program's first report). The

wastewater program was established in June 2016 after $3.6 million was

allocated from the Confiscated Assets Fund to fund it.[36]

The wastewater program tests for 13 drugs, both illicit[37]

and licit.[38]

The data collected captures approximately 14 million Australians (58 per

cent of the population).[39]

2.26

The wastewater program's first report argued that methamphetamine 'is

the highest consumed illicit drug tested across all regions[40]

in Australia'.[41]

Although the wastewater analysis has found methamphetamine use to be high, the exclusion

of cannabis (THC)[42]

has meant this finding conflicts with some other evidence. For example, the 2013 household

survey showed the most common illicit drug used both recently and over participants'

lifetime was cannabis, 'used by 10.2 per cent and 35 per cent respectively of

people aged 14 and over'.[43]

2.27

The wastewater program's first report noted:

-

the capital city sites in Tasmania and the Australian Capital

Territory showed the lowest levels of methamphetamine in their wastewater;

-

methamphetamine detections in South Australian (SA) city sites

exceeded detections in SA regional sites;

-

methamphetamine detections in wastewater over the past five years

at the Queensland and SA sites have shown a consistent pattern of increasing

levels;[44]

-

Western Australia (WA) has the highest levels of methamphetamine

in its wastewater, with detection in both city sites and regional sites far

exceeding the national average;

-

several regional sites in Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania show

high levels of methamphetamine detection; and

-

Australia ranks second out of 18 countries for consumption of

methamphetamine (Slovakia is ranked first).[45]

2.28

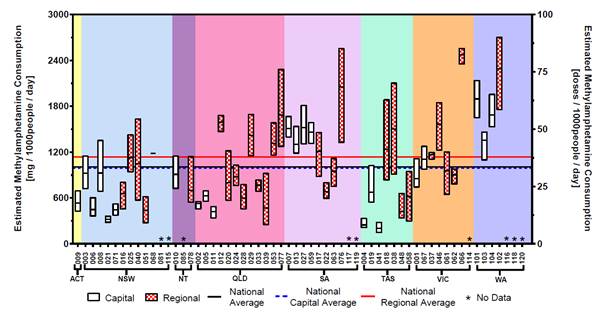

Figure 1 is extracted from the wastewater program's first report. It

shows the estimated amount of methamphetamine consumption per thousand people

and doses per day at each of the testing sites. Data is separated by state and

territory and by capital region and regional area. Finally, the figure

indicates both national capital average and regional average (the red and blue

lines). The figure shows regional consumption rates in WA, SA and Queensland

are far higher than the national regional average. Data from WA and SA show

above average consumption in capital areas.

Figure 1: Estimated methamphetamine

consumption in mass consumed per day (left axis) and doses per day (right axis)

per thousand people. The number of collection days varied from 1–7[46]

2.29

The national wastewater program compliments other wastewater analysis,

such as the University of South Australia's Drug use in Adelaide Monitored by Wastewater

Analysis reports (SA analysis), commissioned by the Drug and Alcohol Services

South Australia. This analysis commenced in 2011 and focuses on metropolitan

Adelaide. Unlike the national program, the SA wastewater analysis includes

heroin[47]

and cannabis.[48]

2.30

The SA analysis for April 2017 showed methamphetamine use in metropolitan

Adelaide slowly increasing between 2012 and December 2016. However, there has

been a steady decline during the reporting periods for 2017.[49]

2.31

On 27 July 2017, the ACIC released the wastewater program's second report.

This second wastewater report found that methamphetamine remained the highest

consumed illicit drug tested across all regions; however, nationally there has

been a slight reduction in methamphetamine detections when compared to the

first reporting period.[50]

Testing sites in the Northern Territory (NT) and Tasmania[51]

did not participate[52]

in the second reporting period.[53]

2.32

The second wastewater report found detections were highest in SA and WA.[54]

For both these states, use appears to have peaked in October 2016 and has

subsequently declined since. Queensland shows a similar pattern, although less

pronounced.[55]

The ACIC concluded that:

The overall picture for methylamphetamine is one of ongoing

and strong demand. While the National Wastewater Drug Monitoring Program has

shown signs that consumption may have peaked in late 2016, it is too early to

say with any certainty if this recent reduction in consumption is the start of

a longer term trend.[56]

Problematic versus non-problematic use

2.33

Despite the number of users and the negative effects of crystal

methamphetamine use, numerous submitters and witnesses advised the committee

that the majority of individuals who use the drug do not demonstrate problematic

use (such as anti-social or criminal behaviour) and live normal and productive

lives. Further, although crystal methamphetamine impacts on a wide range of

individuals from across Australia, there are particular communities and groups

that are more at risk of developing problematic crystal methamphetamine use.

2.34

The Australian Injecting and Illicit Drug Users League observed that a

small minority of people, approximately 15 per cent, use crystal

methamphetamine on a regular or daily basis. The remaining '85 per cent are

engaging in more irregular or occasional use, and perhaps less problematic use—that

is, less than weekly and, for most, less than monthly'.[57]

2.35

The Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations described the majority

of crystal methamphetamine users as non-problematic, that is:

...problematic in being contrary to criminal law but not

necessarily problematic in terms of health use. However, we do acknowledge that

for some people there are problematic levels of ice use...[it is] [n]ot

problematic in terms of being able to function.[58]

2.36

Dr Alex Wodak, President of the Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation

(ADLRF) commented on the differences between problematic and non-problematic use

of crystal methamphetamine. Referring to a series of longitudinal studies for

cocaine and amphetamine, Dr Wodak stated that people who consume 'impressive

quantities' of these drugs 'never came to the attention of law enforcement or

health services for their drug problem' and '[w]hen they started getting some

difficulties, they managed to work out how to pull themselves back'.[59]

Further, Dr Wodak argued that:

...although it does not seem to be something that we would leap

at believing, the evidence is fairly clear that some people are able to use

powerful psychoactive substances for long periods and monitor their own

behaviour to a surprising degree. That is not to say that that is recommended.

I do not recommend it and I am not calling for people to do that, clearly. I

spent the last 30 years dealing with people who got into serious trouble—some

died—caused great misery and anxiety to their families, caused great pain and

suffering in the community generally and were struggling with psychoactive drug

use. So I am not a fan of people getting into trouble with drugs, but we have

to acknowledge the truth, and the truth is: yes, some people can manage to

consume significant quantities of these drugs and somehow not get into trouble.[60]

...people who used large quantities of drugs and started to

have some difficulty pulled themselves up. They would say, 'I'm not going to

take any cocaine for three months,' or six months, or 'I'm only going to take

it on weekends,' or 'I'm not going to spend more than $30 a day on it.' They made

up some rule and stuck to it. After they got it under control, they would go

back. A lot of people monitor their own behaviour in other areas in a similar

way. We have to remember that a lot of people who have problems with

psychoactive drugs in the community do get better by themselves. There is a lot

of resilience in human beings.[61]

2.37

Although problematic crystal methamphetamine use may not eventuate for all

users, the Penington Institute highlighted that problematic use can adversely

affect 'people from all backgrounds and from all geographic areas' and:

...the spread of ice use in Australia has proven that drugs are

available in country areas—in regional and rural and even remote areas—just as

much as they are in the big cities. We have heard stories of the landed big

farming families—very well-to-do families—having problems with ice in their own

families, right down to the most socially disadvantaged and marginalised

communities. The people that get addicted and cause most of the problems

typically have pre-existing mental health issues like depression or anxiety,

and sometimes for those people ice is the first time they have ever experienced

great pleasure in their life. So they go back to it, and sooner rather than

later they are addicted.[62]

Young people

2.38

Evidence presented to the committee identified young people as being

more likely to use crystal methamphetamine and at greater risk of problematic

use. The household survey for 2013 showed that 41 per cent of people between

the ages of 20 and 29 years identified amphetamine as their principal drug of

concern[63]

when seeking treatment.[64]

Amphetamine was identified as an additional drug of concern for

36 per cent of people aged between 20 and 29 years who sought

treatment during the surveyed period.[65]

2.39

Professor Rebecca McKetin, at the time based at the Australian National

University, warned the committee that the uptake of crystal methamphetamine

amongst young people is an indicator of the beginning of an epidemic.[66]

Further, Professor McKetin advised that trends show there has been a 'doubling

of the number of heavy users' of crystal methamphetamine and the 'increase was

strongest in the under-24 age group'.[67]

Although heavy use had increased for people aged 24 or under, the bulk of users

are people in their 30s.[68]

2.40

The committee heard anecdotal evidence from staff involved in front line

treatment of problematic use that there has been an increase in the number of

young people seeking crystal methamphetamine treatment. A particular concern of

Queensland Health was the early age of people initiating the use of crystal

methamphetamine. Historically, those entering treatment programs were 17 or 18

years old, but Queensland Health staff expressed concern that they are now

seeing 15 and 16 year olds coming through their service.[69]

Kidz Youth Community Consultancy advised that it has provided treatment for

children as young as 10 and that adolescents and young people who are

experimenting with crystal methamphetamine are:

...unfortunately more inclined to become [dependent]. It is one

of the characteristics we are seeing with [crystal methamphetamine]. For our

service, probably about 40 per cent of the young people are staying on it quite

heavily, whereas others may binge use and then stop using for a little while

and then binge use, depending on availability and also on whether there are

other drugs around at the time.[70]

2.41

Research by Professor Louisa Degenhardt et al published in the Medical

Journal of Australia indicates that the number of dependent and regular

users of methamphetamine in Australia has increased since 2010, especially in

the 15–24 and 25–34 age groups. The research found:

Rapid uptake of methamphetamine use may still be occurring

outside the largest cities, especially in regional centres where young people

without prior experience of methamphetamine may be exposed to it. The available

data, together with findings reported in this article, suggest a sharp increase

in problematic methamphetamine use among particular subgroups (particularly

young people) in Australia.[71]

2.42

Other factors relating to the uptake of crystal methamphetamine among

young people include its availability and affordability (discussed further at

paragraph 2.105–2.107) and whether those using the drug are a member of one

of the vulnerable categories described in the following sections.

Regional and rural communities

2.43

The committee heard that regional and rural communities are particularly

vulnerable to problematic crystal methamphetamine use. According to the AIHW,

people living in remote and very remote regions 'were at least twice as likely

to have used meth/amphetamines in the previous 12 months as people living in

Major cities and Inner regional areas'.[72]

2.44

Table 9 outlines data provided by the AIHW demonstrating differences in

meth/amphetamine use between those located in major cities compared with those

in regional and remote areas.

Table 9: Meth/amphetamine use,

people aged 14 years or older, by remoteness area (2007 to 2013)[73]

|

|

Ex-users[74] |

Recent users[75] |

| Remoteness/Year |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

2007 |

2010 |

2013 |

| Major cities |

3.9 |

5.1 |

4.3 |

2.5 |

2.0 |

2.1 |

| Inner regional |

3.2 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

1.7 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

| Outer regional |

4.1 |

4.4 |

4.0 |

1.6 |

1.5 |

2.0 |

| Remote/very remote |

5.7 |

7.2 |

8.6 |

3.0 |

4.0[76] |

4.4[77] |

2.45

The ACIC's wastewater program similarly highlighted differences

in methamphetamine use between capital and regional sites across Australia. The

program's first report shows WA with the highest levels of methamphetamine, in

both capital and regional areas.[78]

Regional areas had higher levels of methamphetamine use compared to capital

sites, except for SA and the NT.[79]

2.46

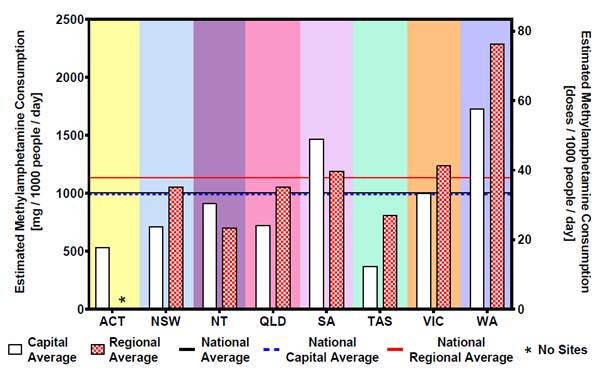

Figure 2 is extracted from the wastewater program's first report. It

shows the estimated amount of methamphetamine consumption per thousand people

and doses per day. Data is separated between capital and regional areas, and by

state and territory. The figure shows both the national capital average and

regional average. Regional consumption in SA, Victoria and WA is above the

national average. WA and SA have higher average consumption of methamphetamine

than other state and territories.

Figure 2: Estimated average

consumption of methamphetamine for capital city sites and regional sites by

state/territory[80]

2.47

According to the National Rural Health Alliance's Illicit Drug use in

Rural Australia report, the causes of illicit drug use in rural and remote

areas are multiple and inter-related: '[d]istance and isolation, poor or

non-existent public transport, a lack of confidence in the future and limited

leisure activities all contribute to illicit drug use in rural communities'.[81]

2.48

The unique challenges faced by regional and rural communities were raised

by a number of submitters and witnesses. Professor Ann Roche from

Flinders University observed that regional and rural communities are more

'likely to experience greater levels of consumption of alcohol and have associated

problems with alcohol' and that '[h]igher levels of most illicit substances

tend to concentrate where they have access to these drugs in regional and rural

areas'.[82]

The reason, according to Professor Roche, is that at a social level:

...where you have communities where there are higher levels of

unemployment and social disadvantage and higher levels of depression and mental

health problems, as you often get in many regional and rural communities, and

fewer life opportunities the individuals in those communities are more

vulnerable to the use of substances that are basically going to make them feel

better when life is not looking particularly good.[83]

2.49

She argued that this issue must be a major consideration for government

when forming appropriate response strategies to problematic drug use in those

communities.[84]

2.50

Another significant issue facing people in regional and rural areas is

accessing treatment services. According to the Victorian Alcohol and Drug

Association (VAADA), individuals from regional and rural communities have less

access to health services, including both primary health and AOD treatments.

Primary health care is limited in regional and rural areas with 3.6 general

practitioners available per 10 000 head of population, compared to 7.6 general

practitioners per 10 000 in metropolitan areas.[85]

Distance, privacy, availability, and simple staffing of services all create

barriers for those in rural communities to access AOD treatments.[86]

2.51

A further hurdle facing people from regional and rural communities, as

described by the Australian Psychological Society (APS), is that once users

return to the 'real world' after seeking treatment, they can find themselves

back in their community 'where everyone is using and [they] are not'. Those trying

to recover from addiction are:

...discharged back to [their] community where there is nothing.

[They] can go from seeing a counsellor every day or once a week in a very

supportive community to being discharged back to [a] community in some regional

place where [they] will get no access to any support at all.[87]

2.52

As discussed above, a number submitters and witnesses stated that people

from regional and rural communities are at a higher risk of developing

problematic crystal methamphetamine use. By contrast, others suggested that

this was not necessarily the case. For example, Drug Arm Australasia argued

that its data does not indicate a 'real difference in presentation rates'

between metropolitan and regional and remote areas. The problem was instead the

visibility of those people using crystal methamphetamine because 'in a metro

region you have the dilution effect that you do not have in a regional area'.[88]

2.53

Professor Paul Dietze, the Deputy Director of the Burnet Institute,

indirectly supported Drug Arm Australasia's comments. He informed the committee

that although there was sufficient anecdotal evidence describing the negative

effects of methamphetamine related problems in regional and remote communities:

...whenever we look closely at those reports, there is really

not much evidence to support them in terms of some of the indicator data that

are there. When I talk about indicator data, I mean things like ambulance

attendances and so forth.[89]

2.54

The problem, as detailed by Professor Dietze, is not necessarily that

there is no problem with crystal methamphetamine use in regional and rural

communities, but there is 'very little reasonable data from regional Australia'[90]

and for this reason:

We do not really have a good picture of what is going on...We

really have not made an investment in trying to find out what is actually going

on, either. We need to be moving beyond anecdote in relation to these parts of

the country.[91]

Indigenous communities

2.55

The committee heard that Australia's Indigenous communities are at a

higher risk of developing problematic crystal methamphetamine use. Indigenous

communities share the same vulnerabilities as other people found in regional

and remote communities;[92]

however, these vulnerabilities are more complex due to other factors such as the

'disparity in the general health of Aboriginal Australians compared to non-Indigenous

Australians'[93]

and the imprisonment rates of Indigenous people being '14 times higher than the

rate of non-Indigenous population'.[94]

The National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Legal Service said that Indigenous

communities 'are at a higher risk of complex trauma because of the legacy of

colonisation, stolen generation policies, loss of land and ongoing racism and

discrimination which places them at greater risk of drug abuse'.[95]

2.56

The AIHW reported that 'Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

were 1.5 times[96]

more likely to have recently used meth/amphetamine than non-Indigenous people'.[97]

However, Youth Off the Streets was concerned that research into Indigenous

communities and drug use has been primarily focused on Indigenous people in

urban areas and there is limited data on usage rates for Indigenous peoples in

regional and remote areas.[98]

According to a 2012–13 National Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander Health Survey, 2.7 per cent of Indigenous Australians living in

non-remote areas reported the use of speed or amphetamine in the past year.[99]

2.57

The NT Police told the committee that there are a small number of known Indigenous

meth/amphetamine users in the NT and that these users are largely from urban

centres. The NT police also advised that there is use in some remote

communities[100]

but that it is not widespread.[101]

The Cape York Health Council commented that across Cape York there is 'probably

only about 18 or so methamphetamine users' but the number of crystal

methamphetamine users is unknown. The Health Council further remarked that 'people

know it is around and report it, but [health services] are not seeing the worst

effects of [crystal methamphetamine] coming into the health services as yet'.[102]

The Cape York Partnership said that 'regions like Cape York are very vulnerable

to drugs like ice' and therefore its representatives were:

...very concerned about this drug and its potential consequences.

But it is 'potential'. We are not saying that ice is prevalent in use or

consequences at this stage in Cape York, thankfully.[103]

2.58

Overall, the committee was made aware of a heightened level of concern

amongst Indigenous communities about the risk posed by crystal methamphetamine

and the proactive approach taken by some communities. Dr Pendo Mwaiteleke from

the Cape York Partnership said that there had been a summit of:

...200 community leaders and representatives. One of the themes

that came across really strongly was that there is actually a growing culture

within the community and community leaders that they do not want ice in the

community and are trying to do everything to make sure that ice does not come

in. At the same time, there are some anecdotes that there have been some

attempts to bring ice into some communities. I made a visit to Aurukun. The

community is very strong. I spoke to quite a number of people, and everyone I

spoke to was very anti-ice. There was a feeling that, if ice were to get into

the community, it is going to be devastating. 'We are trying to solve the

problems that we have; so, if we do not stand up to make sure that ice is not

brought to our community, we know there are going to be very serious

ramifications'.[104]

2.59

The WA Primary Health Alliance informed the committee that there are two

principal concerns regarding crystal methamphetamine use in Indigenous

communities. Firstly, younger Indigenous people are more likely to develop

dependency issues; and secondly, high rates of crystal methamphetamine being

administered intravenously.[105]

As noted above, longitudinal studies confirm that these issues are mirrored in

the Australian population more broadly. However, the evidence indicates that

these issues, combined with the challenges faced by Indigenous communities,

increases the impacts of crystal methamphetamine use on young Indigenous

people.

2.60

The Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia, when asked whether

crystal methamphetamine use more prevalent in Indigenous communities,

responded:

Throughout a number of consultations that we have undertaken

with our sectors, we have seen the shift and we have seen the impacts that

methamphetamines have. It has had an empowering or overwhelming effect on,

particularly, our younger generations. However, it is a combination of alcohol

and methamphetamine usage. Whilst there has been evidence provided that alcohol

use is still higher than methamphetamine use, in our opinion, looking at it

from the Aboriginal community perspective, we see methamphetamine use

overpowering alcohol use. One of the things that we have been adamant about is

that just focusing on methamphetamine use is not going to have a dramatic

impact, because we need to also deal with the social impacts for these young

people who actually have that urge to sample that particular drug.[106]

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender

and intersex community

2.61

Another community that presents with higher use of crystal methamphetamine

is the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) community. The AIHW

reports that people who identify as homosexual or bisexual are 4.5 times more

likely to use methamphetamine than people in the general population.[107]

2.62

The 2016 Sydney Gay Community Periodic Survey reports that since 2012

there has been a significant decline in the use of crystal methamphetamine,

although HIV positive men are disproportionately more likely to report using

the substance.[108]

Of the 3015 men surveyed, 10.4 per cent reported use of crystal

methamphetamine, down from the 11.5 per cent (2846 respondents) in 2015.[109]

2.63

The 2016 Gay Community Periodic Survey for Melbourne reported that

crystal methamphetamine use amongst Melbourne's gay population had remained

stable.[110]

In 2016, 9.9 per cent of the 2886 respondents reported using crystal

methamphetamine, lower than the 11.4 per cent (3 006 respondents) in 2015.[111]

2.64

The AIDS Council of New South Wales advised the committee that LGBTI

people may use drugs:

...for similar reasons as the general populations, the ways in

which this use plays out can be very different for people in [LGBTI]

communities. There is a significant association between the use of

methamphetamine and sex, and that use can impact negatively on sexual health

and HIV, both in terms of transmission and treatment adherence. This

association is very complicated and is worthy of dedicated and specific

government attention.[112]

2.65

The Penington Institute reported that HIV positive men who have sex with

men (MSM) and use crystal methamphetamine are 'more likely to report high-risk

sexual behaviours such as unprotected anal intercourse, compared to HIV

positive MSM who do not use ice'.[113]

The use of drugs such as crystal methamphetamine during sex has become commonly

known as 'chemsex' and is a growing sub-culture within the Australian LGBTI

community.[114]

2.66

Although use of crystal methamphetamine in the LGBTI community is

significantly higher than the general population, its use is not as visible, and

as a result of this lack of visibility:

...its use and impacts are often more private and hidden.

Despite this lack of visibility, the impacts can be just as great. They can

include loss of careers, relationship stress and domestic and family violence,

but rarely do they manifest in the displays of public aggression or dysfunction

that play out in other sections of the community.[115]

The mental and physical effects of crystal methamphetamine

2.67

Amphetamine and methamphetamine have similar effects; however differences

in the chemical structure of methamphetamine increase its potency.[116]

The short term mental effects of use may include:

-

anxiety;

-

fatigue;

-

irritability;

-

hallucinations;

-

suppressed appetite; and

-

insomnia.[117]

2.68

Long term mental effects may include:

-

memory loss;

-

decision making impairment;

-

drug dependency;[118]

and

-

depression, anxiety and psychosis.[119]

2.69

In the short term, the physiologically the effects of crystal

methamphetamine on the body include:

-

an increase in the user's heart rate;

-

hypertension; and

-

constriction of blood vessels.[120]

2.70

In the long term, the physical effects include:

-

an increased risk of stroke;

-

potential for ruptured blood vessels in the brain;

-

decreased lung function;

-

poor dental health;[121]

-

weight loss;

-

skin problems; and

-

sleep problems.[122]

2.71

In addition to the negative effects listed above, submitters noted that of

particular public concern are psychotic episodes and violent behaviour induced

by the use of crystal methamphetamine. These are discussed in greater detail in

the following sections.

Methamphetamine-induced psychosis

2.72

As highlighted by the Australian Drug Foundation (ADF), one of the more

serious health impacts of chronic methamphetamine[123]

use is psychosis. The symptoms of psychosis include confusion, delirium and

panic, which can be accompanied by a range of hallucinations.[124]

The ADF told the committee that users of methamphetamine are:

-

11–12 times more likely to experience psychosis than the general

population;

-

23 per cent more likely to experience clinically

significant psychotic symptoms of suspiciousness, hallucinations or delusions;

and

-

where they are dependent on methamphetamine, three times more

likely than their non-dependent peers to have experienced psychotic symptoms.[125]

2.73

A common manifestation of methamphetamine-induced psychosis is the delusion

of insect and/or parasite infestations under the user's skin.[126]

2.74

Professor McKetin explained that one risk associated with

methamphetamine use is an acute psychosis that manifests as transient paranoia

and 'when people are using this drug, their risk of that paranoid state

increases five-fold from when they are not using the drug'.[127]

A further risk is that transient psychosis for a minority of people can trigger

a more chronic psychological problem. However, there is less evidence to

support this idea and researchers 'do not know whether it has triggered

schizophrenia because they are already predisposed to schizophrenia, or whether

it is just a prolonged episode of methamphetamine psychosis that will

eventually go away'.[128]

Professor McKetin estimated that 20 per cent of users who have transient

psychosis will form some kind of chronic symptoms.[129]

2.75

A paper published by the National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre

(NDARC) in 2005 examined the Sydney methamphetamine market and reported that

psychotic episodes tend to last up to three hours and only 11 per cent of those

people who suffer psychosis attend hospital. Those people who attend hospital

were 'more likely to have more severe long lasting symptoms'.[130]

Of those users that displayed symptoms of psychosis, half felt 'hostile or

aggressive at the time, and one quarter of methamphetamine users exhibited

overt hostile behaviour while they were psychotic, such as yelling at people,

throwing furniture or hitting people'.[131]

2.76

In addition to psychosis, methamphetamine can have a long-term effect on

the cognitive function of users. Professor Roche said that it has a more

damaging effect 'than many other drugs' and:

...within a very short period of time it can severely impact on

your ability to think clearly and function, and it can take one to two years to

regain that normal cognitive functioning that you had previously. That is one

of the very severe potential outcomes of methamphetamine use.[132]

Violent behaviour

2.77

A significant concern for those in regular contact with crystal

methamphetamine users is severe aggression. Many representatives from law

enforcement agencies and frontline health and welfare services reported incidences

of violent behaviour to the committee.

2.78

The Victoria Police observed that some users of crystal methamphetamine

can become quite violent and that police have seen violent behaviour 'play out

in the street' between dealers and users. In comparison, those addicted to

heroin 'did not resort to the level of violence that [users] do with [crystal

methamphetamine]'.[133]

Victoria Police qualified 'that [the] demeanour of the individual probably

enhances it, but violence is a factor that [police] see in a lot of

individuals'.[134]

2.79

The Penington Institute informed the committee that people in the family

violence sector have reported extreme levels of violence associated with

crystal methamphetamine use. The problem, therefore:

...is that the connection between violence and ice is much more

complex than only those people who are addicted or only those people with a

severe problem. It could be people in their first period of use or it could be

someone with an extreme problem'.[135]

2.80

The issue of domestic violence was highlighted by the NDARC, which

argued that the discussion about crystal methamphetamine-related violence has to

date primarily focused on random acts of violence in areas such as Kings Cross.

However, little consideration has been given to domestic violence especially in

concert with alcohol. The NDARC said that it was rare to have an individual

that has taken only one drug and:

If you get a combination of alcohol with crystal

methamphetamine in a certain person who has a propensity for rage than you are

going to find yourself in a very difficult situation. So I think it is probably

not as simple as talking about one drug versus another drug. I think you get

this combination in people, and I think that combination or the effect of that

combination behind closed doors is unseen. We see the street assaults; we do

not see the family violence. I think that, for that very reason, we need to

focus more attention.[136]

2.81

Other submitters and witnesses cautioned against over-emphasising

violence associated with crystal methamphetamine use. In particular, a number

of submitters and witnesses highlighted that while crystal methamphetamine is a

dangerous drug that has significant health and social impacts on individuals

and communities, alcohol is a far bigger problem. For example, Professor Roche

stated that there are difficulties quantifying a greater propensity to violence

among users of crystal methamphetamine and that a number:

...of substances can induce more aggressive and violent

behaviours. Certainly you see it with the stimulants—say, with

methamphetamine—but we also see it with some individuals with alcohol as well.

We have exceptionally high levels of alcohol related violence in our community.

We do not have good data that can compare one group using alcohol and being

violent compared to people being intoxicated with methamphetamine. In both

instances they both become cognitively impaired and so their judgement is

really affected. With methamphetamine you have an elevated threat response. So

often it is not an issue of somebody wanting to behave in a violent and

aggressive way. The drug affects the brain in such a way that they cannot form

appropriate and accurate judgements about what is happening around them and

they feel very threatened and then often can lash out. People do behave quite

differently and it can manifest in violent behaviour in a way that is different

from other substances.[137]

2.82

Similarly, the APS opined that crystal methamphetamine is a problem,

however:

...alcohol

is probably an even greater problem. We are talking about a very low incidence.

I loved reading that submission from Emergency Medicine pointing out that the

number of more serious acute aggressive episodes in emergency departments are

not due to ice, they are due to people with alcohol. It is just that the people

with alcohol eventually fall asleep on you and the person with ice does not. At

the moment, we are certainly seeing sensationalism in this, but alcohol is

significantly more problematic than ice for emergency departments, police and

families.[138]

2.83

Indeed, Dr Wodak advised that:

The violence we see from alcohol at St Vincent's Hospital and

at every emergency department in every hospital throughout the country is

colossal. Every Thursday night, every Friday night and every Saturday night if

you go to any emergency department in the country between 9 pm and 3 am it is

mayhem—and it is largely caused by alcohol.[139]

Ambulance callouts and emergency

department presentations

2.84

Accurate information about ambulance callouts and emergency department

presentations associated with methamphetamine use is difficult to ascertain as

this data is not consistently collected by ambulance services and emergency

departments across the country. There are, however, a number of initiatives to

record this information that provide a valuable insight into the growth of methamphetamine-related

ambulance callouts and emergency department presentations. Two examples are

Turning Point's Ambo Project, which collects Victoria's ambulance callout data,

and the data collected by New South Wales (NSW) emergency departments.

Turning Point's Ambo Project

2.85

Turning Point's ongoing initiative titled Ambo Project: Alcohol and

Drug‑Related Ambulance Attendances records ambulance callout trends

and the substances involved. It began in 1998 in collaboration with Ambulance

Victoria and is funded by the Victorian Department of Health.[140]

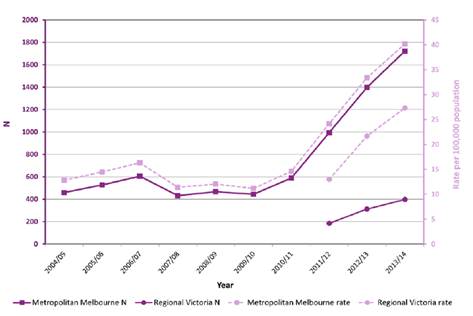

Data collected identifies crystal methamphetamine-related attendances. Evidence

presented in the Ambo Project's 2014–15 report shows a significant growth in

the total number of crystal methamphetamine attendances in Victoria between

2013–14 and 2014–15 with an increase of 47.8 per cent (see Table 10 and Figure

3).

Table 10: Number of attendances,

crystal methamphetamine, in metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria,

2013–14 and 2014–15[141]

|

Metropolitan Melbourne |

Regional Victoria |

All Victoria |

| 2013–14 |

1240 |

296 |

1537 |

| 2014–15 |

1802 (+45.3 per cent increase) |

467 (+57.8 per cent increase) |

2271 (+47.8 per cent increase) |

Figure 3: Crystal

methamphetamine-related attendances by year – 2004–05 to 2013–14[142]

![Figure 3: Crystal methamphetamine-related attendances by year – 2004–05 to 2013–14[142]](~/media/Committees/le_ctte/Crystalmethamphetamine45/First_report/c02_3.jpg)

2.86

Since data collection commenced in 2004-05, Victoria's all amphetamine‑related

ambulance attendances have increased with a notable upward trend since 2010–11 (see

Figure 4).

Figure 4: All amphetamine-related

attendances by year – 2004–05 to 2013–14[143]

2.87

The committee is aware that the National Ice Action Strategy (NIAS) supports

a commitment to expand the Ambo Project to all states and territories[144]

based on the National Ice Taskforce's (NIT) recommendation to establish 'a

system to gather and share national ambulance data drawing on the Victorian

'Ambo Project'.[145]

New South Wales emergency

department presentations

2.88

NSW emergency departments routinely collect data about methamphetamine

presentations.[146]

This data shows that there has been an increase in these presentations: in

2009–10 there were 470 people attending a NSW emergency department with a

methamphetamine-related presentation, in 2015–16 there were 4771 people (see

Table 11).

Table 11: Methamphetamine-related

NSW Emergency Department presentations, persons aged 16 years and over, 2009–10

to 2015–16[147]

| Year |

Number of persons |

| 2009–10 |

470 |

| 2010–11 |

699 |

| 2011–12 |

1162 |

| 2012–13 |

1834 |

| 2013–14 |

2455 |

| 2014–15 |

3627 |

| 2015–16 |

4771 |

2.89

Again, 2010–11 and 2011–12 mark significant upwards shifts in the number

of methamphetamine-related presentations to emergency departments.

Deaths linked to methamphetamine

use

2.90

During the course of the inquiry, the committee was told that deaths

linked to methamphetamine are considered quite rare.[148]

However, data from the 2016 household survey demonstrates that the public

increasingly believes that meth/amphetamine deaths are quite common. Survey

participants ranked meth/amphetamine as the third highest drug thought to cause

deaths in Australia (from 8.7 per cent in 2013 to 19.2 per cent in

2016), after tobacco (23.9 per cent in 2016) and alcohol (34.7 per cent in

2016).[149]

2.91

Available data has shown an increase in meth/amphetamine deaths. The

NDARC reported that accidental drug deaths involving methamphetamine significantly

jumped between 2010 and 2011. An examination of drug-related deaths, hospital

admissions and treatment services by The Guardian suggested that there

were 101 methamphetamine-related deaths in Australia in 2011, 16 more than in 2010.[150]

Estimates have also indicated that up to 170 drug-induced deaths involved

methamphetamine in 2013.[151]

2.92

On 28 March 2017, the Victorian Coroner released statistics on the

number of people who had died in Victoria from drug overdoses. Since 2009,

Victoria has seen the number of drug overdose deaths steadily increase. In

2016, instances where methamphetamine contributed to an overdose death

increased by 40 per cent, from 72 to 116 people. Seventy per cent of

all fatal overdoses in Victoria have been contributed to poly-drug use.[152]

2.93

A further study was released by the NDRI on 31 July 2017. The NDRI

assessed 1649 crystal methamphetamine related deaths between 2009 and 2015 and

found 43 per cent of those deaths were caused by an overdose; 22 per cent of

deaths were due to natural diseases, such as heart disease. The study found the

yearly national death toll had doubled between 2009 to 2015, most of which

occurred in rural and regional areas (41 per cent).[153]

2.94

The NDRI's Professor Shane Darke said the results show that crystal

methamphetamine 'is a serious public health problem and I think we're right to

treat it as such. This is not a beat-up, this is real'.[154]

Professor Darke noted that the number of deaths due to crystal methamphetamine

appeared to have stabilised, but have stabilised at a worrying level.[155]

2.95

Although the rise in deaths related to methamphetamine is a concern,

Professor Roche made a comparison between methamphetamine and the heroin

epidemic in the 1990s:

It is probably helpful to remind people that, in 1999 in

Australia, 1,000 young Australians died from a heroin overdose. That is pretty

catastrophic. I think it is helpful to keep a balance here. We have in

Australia dealt with numbers of very severe drug problems. Death is as catastrophic

as it is going to get, and we know that the death rate associated with

methamphetamine is increasing. So death is the worst possible outcome, and that

is the thing that we work extremely hard to prevent. We then work back in terms

of a hierarchy of harms after that.[156]

Drivers of crystal methamphetamine use

2.96

Despite the negative emotional and health effects of meth/amphetamine

use, people continue to use these drugs throughout Australia. Reasons for

consuming meth/amphetamine, include to:

-

increase productivity (especially in work environments);[157]

-

increase pleasure and enjoyment (including sexual activities);

-

manage emotions;

-

increase a sense of belonging;

-

replicate perceived 'normative' behaviour;

-

expand one's consciousness/heightened awareness; and

-

counter the effects of other drugs and/or avoid the negative

experience of drug withdrawal.[158]

2.97

As described in the ADF's 2015 report Drugs: the facts:

People use drugs to relax, to function, for enjoyment, to be

part of a group, out of curiosity or to avoid physical and/or psychological

pain. Drug use is influenced by a number of factors. Most people use drugs

because they want to feel better or different. They use drugs for the benefits

(perceived and/or experienced), not for the potential harm. This applies to

both legal and illegal drugs.[159]

2.98

Another significant driver of methamphetamine use in Australia is

inequality. The Ted Noffs Foundation called crystal methamphetamine 'a drug

of disadvantage'.[160]

Typically, as with other drugs such as heroin, disadvantaged communities

experience the negative impacts of crystal methamphetamine more so than

advantaged communities. According to the Ted Noffs Foundation,

approximately 80 per cent of their clients are socially and economically

disadvantaged.[161]

Important factors identified by the Ted Noffs Foundation as contributing to

this trend include:

-

intergenerational drug use and children baring witness to the

dysfunctional use of drugs and alcohol;

-

community drug usage that normalises that behaviour for children;

-

people who experience homelessness;[162]

and

-

the difficulties for children to remove themselves from these at

risk communities.[163]

2.99

The ADF also identified that those people most at risk of problematic

drug use are vulnerable through 'no "fault" of their own' and are

significantly influenced by both environmental and biological factors outside

of their control.[164]

These factors include:

-

the emotional distress caused by the lack of employment

opportunities, or mental health problems;

-

children with learning difficulties and dysfunctional family

environments; and

-

the lack of positive role models to guide young people to make

constructive life choices.[165]

2.100

Professor McKetin said there would always be a proportion of the

Australian population that will 'indulge in drug taking, and that is related to

social acceptability of drug use, availability of drugs, and a variety of other

factors'.[166]

However, Professor McKetin emphasised that one key predictive factor in

determining whether an individual develops a dependency for an illicit drug is

that person's resilience.[167]

2.101

Professor McKetin listed other factors that may contribute to a user

developing a problematic drug habit:

Things like mental health problems, low socioeconomic status,

lack of opportunities, all of these things increase the risk of drug problems

developing, as does the availability of the drug in the community, and this is

not to be underestimated because now we have high availability of this drug.[168]

2.102

Dr Wodak highlighted the importance of discussing the role of inequality

in the context of these public health problems, and argued:

A number of public health researchers around the world have

come to the conclusion that countries with high levels of inequality—and that

includes Australia—have much higher levels of mental health and public health

problems such as illicit drug use. It is striking when you compare Australia, a

country with high inequality, to Japan and the Scandinavian countries, which

have much lower levels of inequality. In all those countries the problems they have

with illicit drugs are a fraction of the problems we experience in Australia.

Proving this hypothesis is probably beyond us, but the face validity is such

that we should be doing it.[169]

2.103

The Penington Institute suggested that another contributing factor to

Australia's high levels of methamphetamine consumption is the demand for

intoxication through drugs (both legal and illegal) and opined that 'we have to

deal with the driver for drug consumption, which is, indeed, ourselves. It is

the Australian community; it is not a failure of law enforcement. It is a

failure of the community'.[170]

Price, purity and methods of administration

2.104

The following sections of the report discuss the price, purity and

methods of administration of crystal methamphetamine, and how these have

changed over time.

Price

2.105

The ACIC's Illicit Drug Data Report 2015–16 revealed that the

price of crystal methamphetamine continues to decline, despite record seizures.

Crystal methamphetamine's price per gram across the nation ranged from

$150 to $1200, down from $250 and $1200 per gram in 2014–15.[171]

The price per gram in 2013–14 was $300 to $1600.[172]

It was also reported that a point (a tenth of a gram)[173]

of crystal methamphetamine cost around $20 to $200, compared to $50 to $150 in

2014–15.[174]

2.106

Nationally, in 2015–16 the price per kilogram for crystal

methamphetamine ranged from $75 000 to $280 000 in 2015–16. The price range in

2014–15 was between $120 000 and $280 000.[175]

2.107

Professor McKetin discussed the relationship between the price per

'point' and the availability of crystal methamphetamine. She advised that

crystal methamphetamine's price (in the Sydney market) has remained relatively

stable, suggesting that price has not been a factor driving increased usage:

...the price seems to have been $50 a point forever, at least

in Sydney, and what changes is the purity, the availability. I am sure that

there is a relationship. We saw it with heroin, and it was about the dose

relationship and the way it was marketed as well. It went from something that

you could buy as a gram from a secret dealer that you would have to know

personally for a few hundred dollars, and then the price dropped down to about

$200, which was cheap for a gram, but what happened was that people started

selling it on the street corner for $20 or $30 a cap. That makes it much more

accessible...I actually could imagine common sense is like, if you can pay a certain

amount of money for a drug that is going to give you a good high for four

hours, and you look at the price of alcohol and other drugs, it is going to

play a role.[176]

Purity

2.108

Although the price of crystal methamphetamine continues to decline, the

purity of crystal methamphetamine has increased.

2.109

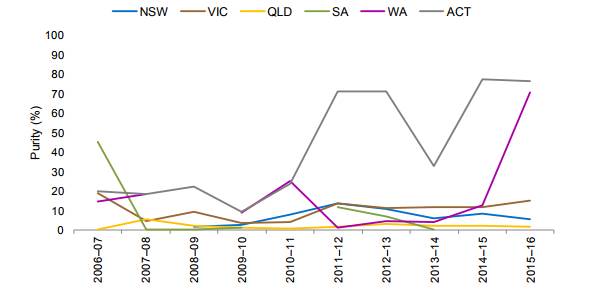

The Illicit Drug Data Report 2015–16 outlines the median purity

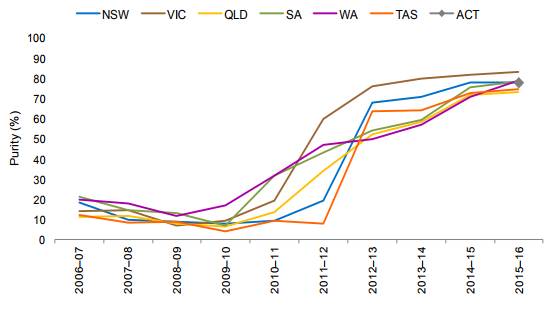

of amphetamine/methamphetamine samples from 2006–07 to 2015–16. Figures 5 and 6

are drawn directly from the report and demonstrate that the purity of methamphetamine

samples in particular have increased drastically between 2010–11 and 2015–16.

Figure 5: Annual median purity of

amphetamine samples, 2006–07 to 2015–16 (by state and territory)[177]

Figure 6: Annual median purity of

methamphetamine samples, 2006–07 to 2015–16 (by state)[178]

2.110

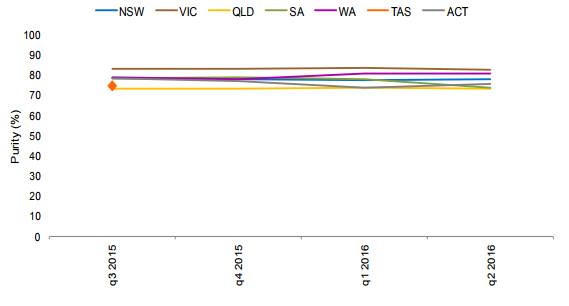

The quarterly analysis of the median purity of methamphetamine samples

in 2015–16 (by state) (see Figure 7) indicates that most states have

methamphetamine with purity between 70 to 80 per cent, and that this level

of purity remained stable over the course of the year.

2.111

Participants in the 2015 IDRS remarked that the purity of crystal

methamphetamine was 'high' and that high purity methamphetamine was considered

'easy' and 'very easy' to obtain.[179]

2.112

A number of submitters discussed the purity of crystal methamphetamine,

with many highlighting the increase in purity as a significant concern.

2.113

The NDARC highlighted that crystal methamphetamine is becoming the preferred

form of methamphetamine and is increasing in purity, observing:

...the community has moved towards a changed form of the

substance. Where traditionally we had seen the powder form more commonly used,

we have seen a move towards ice in its crystalline form. That doubled in that

population survey in 2013 that we were talking about. That means we are seeing

more people taking the crystalline form, which is a purer form, but they are

also taking that form more regularly. They are using it more often. We know

from a lot of previous work that the crystalline form is generally of much

higher purity than the powder form or any of the other forms. If you have an

increase in the pure substance being taken more often then you are going to

find the potential for harm is, indeed, magnified.[180]

Figure 7: Quarterly median purity

of methamphetamine samples, 2015–16 (by state)[181]

2.114

Additionally, the Centre for Population Health at the Burnet Institute spoke

of users not necessarily knowing the purity of crystal methamphetamine each

time it was purchased, a situation that can cause greater harm to the user and

the community. Work done by the Burnett Institute shows:

...when someone goes and buys the drug, and they are buying a

typical amount, they are typically buying, say, 0.1 of a gram. When they used

to purchase it a few years ago, it used to be around 15 per cent pure, and it

would cost a certain amount. Then through the end of 2013, the price they paid

went up a little bit, but the purity had gone up from, say, 15 per cent to

around 70 per cent. So essentially for the same amount of money, you would get

a dramatically increased amount of the drug. People who were not used to using

such high purity drugs were getting into much more trouble, and that is a

really plausible explanation for the increase in ambulance call-outs, the increase

in emergency department presentations, and all of those harms that you

mentioned in the health domain would easily be accounted for by that change in

purity, as well as the change from using powder through to using the crystal

form of the drug, which generally is smoked.[182]

Methods of administration

2.115

Crystal methamphetamine is typically administered into the body either by

smoking (through a glass pipe) or injecting directly into the bloodstream.

According to the School of Social and Political Science at the University of

Melbourne, these two forms of use are 'extremely efficient absorption

mechanisms...which means you get a bolus dose—a big thump of the drug straight

away...[t]hat is going to be a much more intense experience than someone who

snorts the drug'.[183]

As noted by Burnet Institute:

If you smoke the drug, the way in which it is metabolised, or

the body takes it up, the effect is much quicker than if you were to snort it,

as people traditionally did with speed powder.[184]

2.116

Professor McKetin agreed that because crystal methamphetamine is

primarily smoked, it has become a social drug, unlike injecting methamphetamine,

which is a stigmatised behaviour. The ease of passing around a pipe to smoke

crystal methamphetamine means users:

...take it to a party and bang, 20 people are exposed to it. It

is also because when someone becomes dependent, the main way that they will

earn the money to support their drug habit is through dealing. That way they

get a ready supply of wholesale price methamphetamine. In doing that, they sell

it to their friends...That is how the market operates. If you have someone who is

dependent, it is a social drug; they take it to the party and then they start

selling it to those friends. There is a potential for this to spread more

rapidly than what we would have seen with other forms of the drug, because you

have the dependence liability and you have the social aspect.[185]

Poly-drug use

2.117

Poly-drug use—which involves the use of multiple substances at once—is another

issue commonly associated with crystal methamphetamine, especially problematic

users, who 'dabble across a range of substances and are polydrug users'.[186]

2.118

The committee heard that poly-drug use, including crystal

methamphetamine, was a common feature of people seeking treatment for drug

addiction. The Salvation Army placed emphasis on this fact, stating that it

does not generally see methamphetamine use in isolation:

Once people get into treatment services they are usually

polydrug users, so it is very rare to get someone who has only used ice. Very

often we will see people having used opiates such as heroin or benzodiazepines

such as valium to assist them in the cycle of ups and downs; they would use one

of those other drugs to help them come off. Of course, alcohol and ice are quite

a difficult combination we see a lot of, particularly because people are able

to drink a lot more alcohol without feeling drunk while they use ice. The

increased complexity in related health issues is a huge issue for us as well.[187]

National data on illicit drug arrests and illicit drug offences recorded in

Australia's criminal courts

2.119

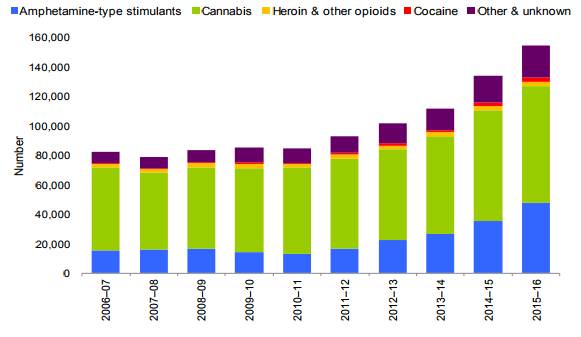

The ACIC's Illicit Drug Data Report for 2015–16 shows that the