Papers on Parliament No. 52

December 2009

Prev | Contents | Next

The Other Metropolis: The Australian Founders’ Knowledge of America

Harry Evans

It is well known that the framers of the Australian Constitution drew extensively upon the United States constitution for many aspects of their creation. This is best demonstrated by the impressive list of the characteristics of the Australian Constitution drawn directly from the American model: the employment of special procedures, different from those applying to normal legislation, for consulting the people in establishing the Constitution and for amending it; the special legal status thereby given to the written constitution; the division of powers between the central and state governments; the prescription of the powers of the national government in the written constitution; the establishment of a constitutional court to interpret and enforce the constitution; the delegation of national legislative power to two elected houses of parliament of virtually equal competence, each representing the electors voting in different electorates and reflecting the geographically pluralistic character of the country. It is equally well known that the founders incorporated a very significant feature alien to the American model and drawn from the British system: responsible or cabinet government, whereby the executive government consists of ministers having the support of a party majority in the lower house of the parliament. If the Constitution is considered as a paper model, however, one would have to say that the institutions drawn from the United States dominate those drawn from the United Kingdom.

That is not how it has worked out in practice. Cabinet government has come to dominate the other elements. This is primarily a matter of the prevailing concept of the Constitution, how the Constitution is regarded by those who work within it, influencing its practical operations, rather than the other way around. From about 1910 until recently there was a remarkable forgetfulness about the origins of the elements of the Constitution. There was an overwhelming concentration on its British antecedents. This eventually led to the automatic and unthinking use of the term ‘Westminster system’ to describe Australian government. To determine how it should work, Westminster norms were consulted and cited as authoritative. Westminster precedents were binding in the conventions of government.[1] Explicit statements by leading founders, that the elements of the Constitution drawn from the United States, generically called its federalist elements, made our system, as designed, very unBritish,[2] were ignored. The federalist elements came to be regarded much as a family regards some large and weighty pieces of furniture acquired by the will of a respected ancestor: it would not do to get rid of them, but they had to be kept out of the living areas. The concept of the Constitution largely explained the way in which the system actually worked. For example, the relative quiescence between about 1920 and the 1950s of the Senate arose from the prevailing view, shared by the senators who determined its activities, that it was a kind of colonial shadow of the House of Lords, notwithstanding the explicit statements of leading founders that it was intended to be nothing of the sort.[3]

This development of constitutional theory and political practice reflected the political and cultural history of the country. The emergence of the Labor Party, which largely had not participated in the federation movement and had little sympathy for constitutional checks and balances and things American, compelled the non-Labor parties to merge and then to line up behind the banner of the Empire and all things British. Both sides of politics thus came to view the apparatus they aspired to control as a ‘Westminster system’. Changes in the world outside reinforced this development. The world view of the statesmen of the 1890s was confident, optimistic and outward looking: in the inevitable triumph of liberalism, democracy and parliamentary government the two great constitutional models provided by the English-speaking peoples were seen as making an equal contribution. The darker horizons of the 20th century discouraged such an outgoing view of the world. The isolation of Britain in the South African war, and the international crises and threats of war leading up to the disaster of 1914–18, encouraged Australians to see themselves as members of a great world Empire which offered some protection to them in their insecurity. There was, to paraphrase Hilaire Belloc, a clinging to nurse in fear of meeting something worse. We are still emerging from that period, and this is reflected in thinking about the Constitution and its history as in other areas of our culture.

Federation celebrations, Pitt Street, Sydney, 1901

nla.pic-vn3789521, National Library of Australia

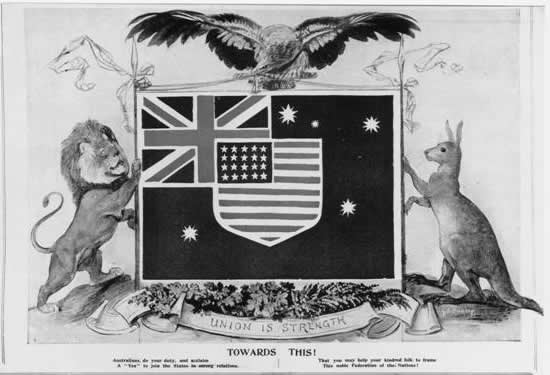

Melbourne Punch, 2 June 1898

This change in perception did not affect only the political elite. The photographs and drawings accompanying this article, illustrating the federation movement and the federation celebrations in 1901, are remarkable for the display of American flags and the adoption of American republican symbolism in connection with federation. This indicates a popular perception that federation owed much to the example of the United States, a perception which also changed as the country entered this century.

It is perhaps a result of historiographical anachronism, reading back into a past epoch the characteristics of an intervening period, that something of a minor myth has grown up about the knowledge the Australian founders had of the United States model on which they so readily drew. It is generally thought that they had only a fairly superficial acquaintance with the constitution and government of the republic for which many of them expressed their admiration.

This view is reflected in the authoritative account of the composition of the Constitution, Professor J.A. La Nauze’s 1972 work, The Making of the Australian Constitution. This study conveys an impression that, in talking about the United States constitution, most of the founders did not know as much as they should have known. It is conceded that Andrew Inglis Clark had a fairly detailed knowledge of American constitutional law and governmental practice, but he was an exception, and, of course, he was not at the convention of 1897–98. La Nauze recounts an embarrassing incident which suggests that, when it came to United States precedents, only Inglis Clark really knew what he was talking about.[4] The great Edmund Barton, no less, acquiesced at the Melbourne session in 1897 in the striking out from the draft of the provision about the original jurisdiction of the High Court in cases in which a writ of mandamus or prohibition or an injunction is sought against an officer of the Commonwealth. Barton and his fellow delegates apparently did not appreciate the reason for this provision. Inglis Clark had to point out to the great man by telegram from Hobart that the provision was designed to avoid the application of an early decision of the United States Supreme Court, in Marbury v Madison, which could otherwise be followed in Australia and cause difficulty for Australian law. The judgement is now regarded as a foundation of American constitutional law and is well known to all students of that law. Recent controversy about judicial review has added to its importance, and it is not clear that it had the same status one hundred years ago. In any event, Barton, and those delegates he said he consulted, appear to have been ignorant of the case and the point in issue.

In the absence of Inglis Clark, delegates to the 1897–98 convention, according to La Nauze’s account, relied very heavily on a book by an Englishman, James Bryce’s The American Commonwealth, which was the ‘bible’ of the convention.[5] In 1891 their knowledge was fairly superficial, but there was ‘evidence of much more serious homework in 1897–8’. Even so, apart from Bryce, they relied on ‘standard studies and commentaries’.[6]

A more detailed examination of the founders’ references to the United States indicates that, while they did not recall Marbury v Madison, they were more knowledgeable than La Nauze’s account, and the general impression largely flowing from it, would suggest. There is not space here to recount such a detailed examination. This thesis may be illustrated, however, by a consideration of the debate in the conventions about the Senate, perhaps the most conspicuous borrowing from the United States. The exchanges about the Senate, which pitted the federalists, the devotees of the example of the Great Republic, against the responsible government men, followers of the British-is-best school, suggests that the state of their knowledge was fairly good.

In the first place, they appear to have been better read than La Nauze suggests. Even in 1891 they were not confined to Bryce, and references were made to the writings of J.R. Lowell, former United States ambassador to Britain, and Woodrow Wilson, then a law professor.[7] Several delegates appear to have closely read the accounts of the debates at the 1787 Philadelphia convention at which the United States constitution was drafted. These accounts are now seldom referred to except by close students of American constitutional history. Thus, at the 1891 convention, when the more serious homework had not been done according to La Nauze, Richard Baker interposed when an impasse appeared to have been reached about the Senate, to suggest that perhaps a Philadelphia precedent should be followed by the establishment of a ‘committee of compromise’ to consider the views and the options.[8] In 1897 at Adelaide, Bernhard Wise pointed out that the somewhat acrimonious debate on equal representation in the Senate had all been played out before at Philadelphia, and had included a contribution, quoted by Wise, by a delegate from Delaware named George Read.[9] At Adelaide Patrick Glynn referred to The Federalist no. 72, noting that it was not certain whether it was written by Hamilton or Madison.[10] At Sydney in 1897 Josiah Symon quoted the correspondence of Samuel Adams.[11]

Perhaps delegates were led to this sort of knowledge by the ‘standard commentaries’. They appear to have used the latter, however, more as sources of institutional theories and arguments than of facts or law. In 1897 at Sydney, Wise, referring to the wisdom of the scheme of representation in the Senate, quoted Story’s Commentaries, a work which is included in La Nauze’s list of the literature to which delegates referred, not as a legal text but as an exposition of the theory of representation.[12] It is true that, in 1891, when discussing a proposal to have the Senate directly elected rather than appointed by the state legislatures as in the United States, Charles Kingston quoted a passage from Bryce,[13] but this, as will be suggested, rather denotes an alertness to developments in the United States than an over-reliance on that source.

Apart from their book-learning, some of the delegates displayed an acquaintance with American government and politics and an up to date knowledge of how they worked in the 1890s. An example is provided by an exchange between Alfred Deakin and John Cockburn at the 1891 convention, in which the latter referred to the way in which positions in the US Senate had come to be contested in state legislative elections and were the subject of much political manipulation. Deakin was alert to a significant difference between the Australian colonial legislatures and those of the states in the United States: in all states both branches of the latter were elected and had no equivalent of the nominated upper houses of Australia.[14]

Kingston improved on quoting Bryce: he had conferred with the author and invited comments on the draft Australian Constitution, which resulted in Bryce’s endorsement of the proposal for senators to be directly elected as a cure for the problems of the US Senate.[15]

The delegates were also not lacking in practical experience. Inglis Clark was not the only founder to visit America. Old Henry Parkes regaled the 1891 convention with an account of his visit to Washington in 1882 on a trade mission, during which he conversed with the President, the Secretary of State and congressional leaders, and was disgusted to discover the Senate meeting in closed session (a practice which it continued in relation to some business until 1929).[16] At Sydney in 1897, Josiah Symon referred to his travels around the United States and his talks with American political figures.[17] Kingston also referred to discussions he had while in America.[18] Those who argued against equal representation of the states in the Senate constantly referred to the anomaly of Nevada, which was entitled to elect two senators in spite of its tiny population and its domination by a single mining industry. Deakin, in supporting equal representation in the Senate, was able to trump this argument: he had visited Nevada, but a first hand examination of it had not altered his view.[19]

A seemingly advanced knowledge of developments in the United States also explains the significant change which was made between the 1891 constitutional convention and that of 1897 from a Senate appointed by the state parliaments to one directly elected by the people of the states. The 1891 draft constitution bill provided for the Senate to be appointed by the state legislatures; in this it followed the constitution of the United States, under which the US Senate was so appointed until an amendment in 1913. The 1897 bill provided for the proposed Australian Senate to be directly elected.

This change is conventionally attributed to the ‘advance of democracy’ in the Australian colonies in the period between the two conventions. Quick and Garran’s Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth offers this explanation, while also referring to evidence placed before the 1897 convention of the unsatisfactory nature of the US system.[20] La Nauze in effect adopts the advance of democracy thesis. He also conveys the impression that the change in the draft bill emerged from a ‘secret’ drafting committee and simply reflected the prevailing view amongst the delegates.[21]

Events usually have many causes, and the ‘advance of democracy’ was undoubtedly one of the causes of the change of approach to the composition of the Senate. There was an upsurge of democratic sentiment in the 1890s, of which much evidence may be cited. Further evidence from drafts of the Constitution is provided by proposals for amending the Constitution: the 1891 bill, again following the United States model, provided for amendments to be approved by elected conventions in each of the states; the 1897 bill adopted the more democratic process of approval of amendments by the electors voting in referendums.

Apart from the advance of democracy in Australia, however, a corresponding advance of democracy in the United States had resulted in events which made it fairly clear that the US Senate was in the process of being converted to a directly elected body. The model on which the 1891 bill was based was about to disappear. It took another 16 years for the US constitution to be changed, but by 1897 the change was in process and it looked as if its completion was not far off. It was the Australian founders’ knowledge of this which was decisive in making the change in Australia.

The contention that the Senate should be elected was not new to the United States in the 1890s. It was advanced at the Philadelphia convention in 1787, and a change to direct election was suggested throughout the nineteenth century, for example in the 1860s by Andrew Johnson. In the 1890s, however, it was taken up by the reform movement, which flourished at that time, and which made great gains between 1891 and 1897.

The aim of the reform movement was to break the control of party machines and party bosses over nominations and elections. The main weapon of the movement was state legislation requiring primary elections. In the 1890s primary elections were adopted in many states. They allowed voters to select candidates directly. Primaries were held for candidates for the Senate, with the expectation, not always fulfilled, that the candidates who won the primaries would be appointed by the state legislatures. A growing number of senators were therefore in fact elected by the people and owed their places to the electors rather than the state houses. There were moves to regularise this change by an amendment of the constitution. From 1894 onwards various state legislatures petitioned the Congress to initiate such an amendment. The proposed amendment was first passed by the House of Representatives in 1893 and repeated in following years.

These developments, which fell largely between the two Australian conventions, were well known to the delegates to the 1897 convention. In debate in the convention before the ‘secret’ committee was appointed, several delegates expressed the view that the Senate should be directly elected, with reference to the situation in the United States. The recent developments there were set out in an article by Senator John Hipple Mitchell of Oregon, published in the journal The Forum in June 1896. Mitchell was a promoter in the Senate of the proposed constitutional amendment. His article was quoted at length to the convention by Isaac Isaacs, who favoured direct election of senators.[22] The article did not simply refer to the unsatisfactory features of the appointment of senators in the United States, but provided a fairly detailed account of the progress of the reform movement in relation to direct election of senators, including action recently taken in the Congress.

If anything was decisive in steering delegates towards popular election of senators, it was this intelligence of American events. It was not merely a matter of pointing out the failings of US Senate appointments, as Quick and Garran implied, but of foreseeing the success of the US reform movement and anticipating a similar success in Australia. It has already been noted that the 1891 convention had been directed to a passage in Bryce’s book referring to a proposal to change the US Senate to a directly elected body. This did not influence that convention to change to direct election. By 1897 it appeared from the Mitchell article that the proposal was well on the way to achievement. At the 1891 convention those favouring direct election of senators were in a minority; at the 1897 convention they were an overwhelming majority. Bryce’s ‘bible’ was not decisive; knowledge of recent events and a more direct source appear to have had greater influence.

It was ironic that Isaac Isaacs was in the majority. His political radicalism overcame his constitutional theories on this occasion. He was one of those who wanted a purely British system of government: legislative power vested in an Australian version of the House of Commons, and a cabinet formed in that chamber. He had little time for the checks and balances of a federal system, particularly an upper house representing the states equally and with equal legislative powers. His fellow anglophiles, while forced to adopt such institutions of federalism, never really accepted them as legitimate. They preferred to pretend, before and after 1901, that they had bestowed upon the country a British system of cabinet government, albeit with a few superfluous federalists excrescences which could be ignored most of the time. The change to a directly elected Senate, however, made it more difficult to maintain this pretence.

The federalists, those who favoured the institutions of federalism such as the Senate, quickly realised that a conceptual as well as an institutional shift was involved in the change to direct election. If the Senate was to represent the states as bodies politic in the federation, how much more effectively could it do so if it represented the people of the states rather than the state parliaments. The leading federalists, such as Richard Baker, were usually careful to refer to the Senate representing the people of the states rather than simply representing the states. This was music to the ears of the radical democrats who were also federalists, such as John Cockburn, who were federalists largely because they associated democratic reform with state-level politics.[23]

The responsiveness of the convention not only to democratic sentiment in Australia but to the reform movement in the United States has been somewhat obscured. This may be because the anglophiles, and subsequently conservative and Labor politicians and academics, were not anxious to emphasise the federalist character of the Constitution or its borrowings from what some convention delegates called the Great Western Republic. The notion that the founders did not have an extensive knowledge of the United States may be a subsidiary aspect of this view.

Whatever the validity of this analysis, it is clear the founders’ knowledge of America should not be underestimated.

1. For the Westminster hegemony and the rediscovery of the federalist heritage, see C. Sharman, ‘Australia as a compound republic’, Politics, May 1990, pp. 1–5; B. Galligan, A Federal Republic: Australia’s Constitutional System of Government.Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995. The latter points out that the High Court, in the Engineers case, joined the retreat from federalism.

2. Official Record of the Debates of the Australasian Federal Convention (hereafter Debates),Richard Baker, 17 September 1897, p. 789. The convention debates are online at www.aph.gov.au/senate/pubs/index.htm.

3. Debates, Richard Baker, 17 September 1897, p. 784.

4. J.A. La Nauze, The Making of the Australian Constitution. Carlton South, Vic., Melbourne University Press, 1972, pp. 233–4. Another account of the incident, with a similar interpretation, is in A.C. Castles, ‘Andrew Inglis Clark and the American constitutional system’ in M. Haward and J. Warden (eds), An Australian Democrat: The Life, Work and Consequences of Andrew Inglis Clark, Hobart, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, 1995, pp. 15–18.

5. La Nauze, op. cit., pp. 18, 273.

6. ibid., pp. 274–5.

7. Debates, Richard Baker, 17 March 1891, p. 439, 1 April 1891, pp. 543, 545.

8. Debates, 16 March 1891, p. 393.

9. Debates, 25 March 1897, pp. 105–6.

10. Debates, 15 April 1897, p. 664.

11. Debates, 10 September 1897, p. 296.

12. ibid., pp. 325–6.

13. Debates, 2 April 1891, pp. 596–7.

14. ibid., p. 592.

15. Debates, 10 September 1897, pp. 287–8.

16. Debates, 13 March 1891, p. 318.

17. Debates, 10 September 1897, pp. 297–8.

18. ibid., p. 287.

19. ibid., p. 336.

20. J. Quick and R.R. Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth. Sydney, Angus & Robertson, 1901, p. 418.

21. Quick and Garran, op. cit., pp. 124–5.

22. Debates, 26 March 1897, pp. 176–7.

23. Debates, Richard Baker, 23 March 1897, p. 28, John Cockburn, 30 March 1897, p. 340.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top