Chapter 2

Research and Development Tax Incentive

The existing R&D tax concession

2.1

The legislative provisions that govern the existing tax concessions for

R&D are set out in sections 73B to 73Z of the Income Tax Assessment Act

1936 (ITAA 1936) and Part IIIA of the Industry Research and Development

Act 1986 (IR&D Act). These provisions, which were introduced to

encourage research and development in Australia and make eligible companies

more internationally competitive,[1]

provide concessions for particular expenditure on defined activities.

2.2

There are four elements to the existing R&D tax concession:

- a 125 per cent tax concession that provides claimants with a

deduction of 125 per cent of eligible expenditure incurred on Australian owned

R&D activities;

- an R&D tax offset that enables small companies with an annual

turnover of less than $5 million and whose aggregate Australian-owned R&D

expenditure is more than $20,000 but less than $1 million[2]

to obtain a tax offset equivalent to their tax concession entitlement;

- an incremental 175 per cent premium tax concession for those companies

that increase their R&D expenditure in Australia relative to their average

R&D expenditure over the previous three years; and

- an incremental 175 per cent international premium tax concession

available for increases in foreign-owned R&D activities carried on by a

company incorporated in Australia.[3]

2.3

Responsibility for administering the current concession is split between

the Commissioner of Taxation and the Innovation Australia Board. To access the

concession a company must have registered its R&D activities with

Innovation Australia before then completing the relevant sections of their

income tax return.[4]

2.4

The cost of the current scheme has been increasing over the past few

years as the value of R&D claimed has risen sharply (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 – Value of

R&D claims

| |

2005-06

$mn |

2006-07

$mn |

2007-08

$mn |

|

R&D concession (not

including incremental) |

9,620 |

12,310 |

14,870 |

|

R&D incremental

concession |

820 |

1,230 |

1,250 |

|

R&D refundable tax

offset |

290 |

310 |

390 |

|

Total value of

claims |

10,730 |

13,850 |

16,510 |

Source: Australian Taxation

Office, Answers to Questions on Notice, Senate Economics Legislation Committee,

Additional Estimates, 10-11 February 2010, Question aet 36, p. 2.

2.5

The numbers of claimants under the various components of the current

scheme are shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Current

R&D tax concession scheme

| |

Estimated cost, $mn,

2009-10 |

Number of companies

registered, 2007–08 |

Reported R&D, $bn,

2007–08 |

|

125% concession |

650 |

2,986 |

4.6 |

|

Tax offset |

522 |

2,712 |

0.8 |

|

175% premium |

350 |

1,473 |

8.5 |

|

International premium |

|

7 |

0.0 |

|

combinations |

|

576 |

0.3 |

|

Total |

1,522 |

7,754 |

14.2 |

Source: derived from Innovation

Australia, Annual Report 2008-09, p. 25; information from DIISR.

2.6

The Government hopes the changes in the bill will open the incentives to

more of Australia's two million businesses:

At the moment 100 firms are getting around 60 per cent of the

total, the equivalent, in this financial [year], of $1.5 billion. The current

scheme, which was a good scheme when it was introduced, is in need of

renovation. There are going to be a lot of folk out there—the 100 firms—that

have a huge vested interest in keeping the current scheme the way it is. We are

actually in the business of helping the 8,000 firms that are currently

registered—and I would like to see a lot more firms. Given that we have two

million firms in this country, the fact that we have only 8,000 registered for

the scheme strikes me as way short of what we need to do as a country.[5]

Rationale for the proposed changes

2.7

The changes set out in the Tax Laws Amendment (Research and Development)

Bill 2010 and the Income Tax Rates Amendment (Research and Development) Bill

seek to modernise the existing incentive by cutting red tape and providing a

more targeted incentive thereby ensuring that 'public support for business

R&D is consistent with the underlying rationale for government intervention

and delivers value for money for taxpayers.'[6]

2.8

The bills currently before the parliament will achieve these stated

objectives by repealing the complex provisions that currently apply and

replacing them with a much simpler tax offset. The rate of the offset and

whether or not it will be refundable will be dependant on the entity's

turnover.[7]

2.9

Like the existing test, the offset will only be accessible where the

company involved is investing in eligible R&D activities, the definition of

which will be redefined by the passage of the Tax Laws Amendment (Research and Development)

Bill 2010.

2.10

It should be noted that the IR&D Act will continue to operate in

concert with the new Division 355 – Research and Development in the Income

Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997).

2.11

The after tax benefit[8]

of the different R&D concession rates over time are set out in Table 2.3.

2.12

Under the existing regime, eligible entities are entitled to claim a

deduction. The amount of the deduction is used to reduce the taxpayer's taxable

income. Under the proposed scheme, either a refundable or non-refundable offset

will be available. Offsets are applied to reduce the calculated tax liability,

therefore, if there is an excess the taxpayer is entitled to a refund unless

their turnover exceeds $20 million, in which case, the excess offset will be

carried forward to be applied against their tax liability for the next year.

Table 2.3

|

Financial year(s) |

Tax rate (%) |

Incentive rate (%) |

After tax benefit |

|

87-88 |

49 |

150 |

24.5 |

|

88-89 to 92-93 |

39 |

150 |

19.5 |

|

93-94 to 94-95 |

33 |

150 |

16.5 |

|

95-96 to 96-97 |

36 |

150 |

18.0 |

|

96-97 to 00-01 |

36 |

125 |

9.0 |

|

Current |

30 |

125 |

7.5 |

|

Ongoing (IF BILL NOT

PASSED) |

28 |

125 |

7.0 |

|

IF BILL PASSED: |

|

|

|

|

2010-11 (turnover less

than $20 million) |

30 |

150* |

15 |

|

2010-11 (turnover greater

than $20 million) |

30 |

133* |

10 |

Source: Adapted by Secretariat

from Victorian Innovation Economy Advisory Board, 2006.

*equivalent calculated under the proposed regime of a refundable tax offset.

Role of AusIndustry/Innovation Australia

2.13

Under the existing regime, the Innovation Australia Board, with the

assistance of AusIndustry officials, is responsible for registering the R&D

activities of eligible companies seeking to access the concession annually.[9]

2.14

Registration is not an indication that the activities of the company

seeking to access the concession are eligible R&D, rather entities self

assess and register. The Board then reviews registered companies through its

internal assessment process or on referral from the Tax Office.[10]

2.15

When reviewing registrations, the Board reviews the facts to determine

whether or not the facts fall within the words of the definition.[11]

2.16

Innovation Australia determines the eligibility of R&D activities;

the Tax Office considers the eligibility of R&D expenditure.[12]

The role of Innovation Australia is discussed in Chapter 7. R&D activities

and R&D expenditure are defined in Chapter 5.

2.17

The existing R&D concession regime operates in an environment of

self assessment; the Board and the Tax Office provide guidance material to

assist companies seeking to access the concessions to self assess their eligibility.

This is consistent with the broader operation of Australia's tax system.

2.18

This will not change under the amendments set out in the bills; entities

will still be required to assess their eligibility for the R&D tax

incentive under the new rules of Division 355. They will however be required to

identify, on application, both their core and supporting R&D activities.

2.19

This obligation, which will be introduced by the bill, will be

accompanied by a requirement that Innovation Australia then confirm or reject

the applicant's claim.[13]

Although the amended provisions provide for greater integrity in the

application and registration process, the explanatory memorandum to the bill

notes at paragraph 5.28 that:

As the new R&D tax incentive is a self assessment regime,

the majority of applications to the Board will be registered without formal

examination in relation to the activities conducted in the income year in

question...[14]

2.20

Guidance, and therefore a degree of certainty, will be provided to

companies through the Board's issue of public advice and advisory materials and

generalised public findings about activities.[15]

Consultation undertaken and changes made

2.21

As the following discussion and Table 2.4 shows, there have been a

number of public reviews of the scheme.

Table 2.4:

Consultations on R&D assistance

| |

Year |

No. of submitters |

No. of public hearings |

|

Productivity Commission |

2007 |

157 |

2 |

|

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics,

Finance and Public Administration |

2007 |

50 |

13 |

|

Cutler review, Venturous Australia |

2008 |

>700 |

9 |

|

Treasury – consultation paper |

2009 |

197 |

|

|

Treasury – first exposure draft |

2009 |

131 |

|

|

Treasury – second exposure draft |

2010 |

55 |

|

|

Senate Economics Legislation Committee |

2010 |

31 |

2 |

2.22

Following the 2009-10 federal budget announcement, the Government

commenced a consultation process in September 2009 when an initial discussion

paper was released. The Treasury received 197 submissions in response to the

release of the paper. Draft legislation was then exposed for public comment in

December 2009, the Government announcing that:

The draft legislation follows through on [the] commitment to

deliver a more generous, more predictable, and less complex tax incentive by

replacing the outdated and complicated R&D Tax Concession...[that would] help

boost the competitiveness of the Australian economy.[16]

2.23

Following that round of public comment, a revised exposure draft was

released on 31 March 2010.[17]

Final adjustments were made before the bill was introduced into the House of

Representatives on 13 May 2010.

Earlier studies

2.24

The precursor of the current scheme was introduced as part of Senator

Button's 1985 industry reforms. The programme was cut back in 1996 (Table 2.3) but

expanded again in 2001. There have since been a number of studies of the scheme

which formed the basis of the bill. The conclusions of the most recent of these

are given below.

Productivity Commission, 2007

2.25

A major study by the Productivity Commission in 2007 concluded:

The extent to which the basic R&D tax concession stimulates

additional R&D is low, particularly for large firms...Access to the 125 per

cent R&D tax concessions should be restricted to small firms.[18]

2.26

The PC attempted a cost-benefit analysis of the scheme but the results

were inconclusive, with the net benefits found to lie in a range of -$234

million to +$231 million.[19]

Department of Industry, Tourism and

Resources, 2007

2.27

The Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources issued a report

prepared by their Steven Playford, How R&D Assistance Influences Company

Behaviour: A Survey Investigating Behavioural Additionality Effects of the

R&D Tax Concession Program, in 2007. A survey of recipients of the

R&D tax concession found that 73 per cent said that they spent more on

R&D as a result of the concession.[20]

(Further information about the study is given in Chapter 3.)

House of Representatives Economics

Committee, 2007

2.28

A 2007 report by the House Economics Committee concluded:

There are doubts about the extent to which the existing

R&D tax concessions are effectively inducing additional R&D, especially

given the reduction in the company tax rate.[21]

Cutler review, 2008

2.29

The report by an expert panel chaired by Dr Terry Cutler, entitled Venturous

Australia, reviewed the national innovation system. The panel established a

specific working group to examine R&D tax concessions.

2.30

The conclusions of the panel on the R&D tax concession were:

Since its inception the R&D Tax Concession has been

subject to several problems. Instead of being tackled directly in the design

and funding of the central concession, these problems have typically been

tackled by establishing additional programs. While the Concession offers no

benefits to firms until they are in tax profit, many of Australia's most

innovative firms remain cash strapped and in tax loss for many years...Further,

the Concession is accounted for 'below the line' and so is often invisible in

company financial decision making....The International and Premium schemes should

be terminated and the basic concession increased and recast as a 40 per cent

tax credit...For small firms we propose increasing the rate of assistance

further...[22]

Henry Tax Review, 2010

2.31

The Report on Australia's Future Tax System, generally known for

its chair as the Henry Tax Review, comments:

Where the research and development of a firm generate

spillover benefits for others, the social returns from research and development

may be greater than the private returns. A tax-preference or government

expenditure that appropriately targets such spillovers may therefore be

beneficial and improve overall productivity. But where a subsidy is

inappropriately targeted, such incentives can bias the allocation of resources

in the economy and actually reduce productivity.[23]

2.32

The Report, however, cites the recent reviews of innovation

policy as a reason for it not to give detailed consideration to the matter.[24]

Committee View

2.33

In summary, the design of the new R&D assistance in the bill has

been informed by a number of inquiries with broad consultation.

Research and development in Australia

2.34

Total R&D expenditure by businesses in Australia was around $14.4

billion in 2007-08. While small business employs about half the workforce, it

only does about a tenth of R&D, which is dominated by large firms (Table 2.5)

Table 2.5: R&D by

size of firm, 2007-08 (percentage share)

|

Employment size |

|

|

Less than 4 persons |

3 |

|

5 to 19 persons |

8 |

|

20 to 200 persons |

19 |

|

Over 200 persons |

70 |

Sources: ABS, Research and Experimental Development, Business

2007-08, cat. No. 8104.0, p. 12.

2.35

About a third of R&D expenditure is on labour, with capital

expenditure only a very small element (Table 2.6).

Table 2.6: R&D by

type of expenditure, 2007-08 (percentage share)

|

Labour costs |

34 |

|

Other current expenditure |

60 |

|

Land and buildings |

1 |

|

Other capital expenditure |

4 |

Sources: ABS, Research and Experimental Development, Business

2007-08, cat. No. 8104.0, p. 12.

2.36

The majority of R&D comprises experimental development with pure

research only accounting for a very small proportion of business R&D (Table

2.7).

Table 2.7: R&D by

type of expenditure, 2007-08 (percentage share)

|

Pure basic research |

1 |

|

Strategic basic research |

5 |

|

Applied research |

32 |

|

Experimental development |

62 |

Sources: ABS, Research and Experimental Development, Business

2007-08, cat. No. 8104.0, p. 12.

2.37

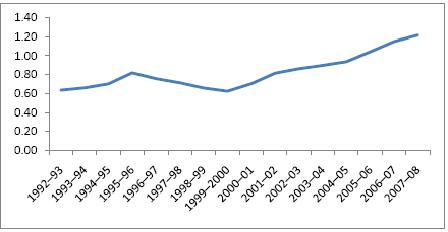

Business R&D has increased relative to GDP in the past decade (Chart

2.1).

Chart 2.1: Business

R&D: per cent to GDP

Source: derived from data in ABS 5204.0, Australian System of

National Accounts, 2008-09; and ABS 8104.0, Research and Experimental

Development, Businesses, 2007-08.

2.38

Manufacturing, mining and professional services are the largest

investors in R&D, both in absolute terms and relative to their

contributions to GDP. (Table 2.8)

Table 2.8: Business R&D

by industry, 2007-08

| |

$ bn |

% to gross value added |

|

Manufacturing |

4.3 |

3.9 |

|

Mining |

3.3 |

4.1 |

|

Professional, scientific and technical services |

2.2 |

3.2 |

|

Financial and insurance services |

1.4 |

1.2 |

|

Wholesale trade |

0.8 |

1.6 |

|

Information media and telecommunications |

0.8 |

2.3 |

|

Construction |

0.6 |

0.7 |

|

Transport, postal and warehousing |

0.2 |

0.3 |

|

Electricity, gas, water and waster services |

0.2 |

0.7 |

|

Agriculture, forestry and fishing |

0.1 |

0.4 |

|

Administrative and support services |

0.1 |

0.3 |

|

Rental, hiring and real estate services |

0.1 |

0.2 |

|

Retail trade |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Other services |

0.1 |

0.3 |

|

Health care and social assistance |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Arts and recreation services |

0.0 |

0.3 |

|

Education and training |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Public administration and safety |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total |

14.4 |

1.4 |

Source: derived from data in ABS

5204.0, Australian System of National Accounts, 2008-09; and ABS 8104.0,

Research and Experimental Development, Businesses, 2007-08.

International comparisons of R&D assistance

2.39

An international comparison by two Treasury economists suggested that

Australia provides relatively generous tax concessions for R&D.[25]

2.40

A recent UK study has Australia ranked around the middle for its support

for corporate R&D (Chart 2.2).

Chart 2.2: Rates of

subsidy for R&D, 2007

Source: Dyson, Ingenious Britain, 2010, p. 53.

2.41

A comparison by KPMG also has Australia currently ranked in the middle

of 10 OECD economies, but moving up to first place once the new scheme is in

place (see Chapter 8).

2.42

Medicines Australia drew the Committee's attention to a comparative

study by a Canadian accountancy firm which suggests the new scheme will place

Australia in a favourable spot.[26]

The study is summarised in Table 2.9.

Table 2.9: R&D

Tax Incentives – International Comparison

| |

Started |

Benefit rate (%) |

Eligible location |

| |

|

tax deduction |

refund rate |

|

|

Australia-now |

1985 |

125 |

|

>90% in Aust. |

|

Australia-proposed |

2010 |

|

40-45 |

|

|

Austria |

1988 |

125 |

|

within EU |

|

Canada |

1986 |

|

20-35 |

>90% in Canada |

|

France |

1983 |

|

30-50 |

within EU |

|

India |

1997 |

150 |

|

in India |

|

Ireland |

2004 |

20 |

and 12.5 |

within EU |

|

New Zealand |

2008 |

|

15 |

predominantly NZ |

|

South Africa |

2006 |

150 |

|

in South Africa |

|

Spain |

1995 |

|

25 |

|

|

United Kingdom |

2000 |

130-175 |

|

anywhere |

|

United States |

1981 |

|

20 |

in USA |

Source: based on Scitax Advisory Partners, Overview of Research &

Development Tax Incentives in Selected Global Knowledge Economies, April 2010;

available at http://www.scitax.com/pdf/Scitax.International.RD.Tax.Credit.Survey.Table.08-April-2010.pdf.

2.43

A recent UK study noted the widespread use of tax incentives for

R&D:

Even countries with low corporation tax have instigated a

separate regime to encourage R&D investment. For example, Ireland lowered

its corporation tax to 12.5% in 1998 but followed that with a new R&D tax

credit in 2004. Similarly, Singapore has a twin policy of low corporation tax

rates supplemented by an attractive R&D tax credit system. The swell of

investment in France highlights how countries with high corporation tax rates

can stimulate investment with the intelligent use of tax credits.[27]

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page