Introductory Info

Date introduced: 24 March 2021

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Health

Commencement: Sections 1 to 3 commence on Royal Assent. Schedule 1 commences on the earlier of Proclamation or six months after Royal Assent.

The Bills Digest

at a glance

Mitochondrial disease is a group of

conditions that can cause serious health issues and, in severe cases, can cause

death in childhood. There is no known cure for mitochondrial disease.[1]

Mitochondrial donation is an assisted reproductive

technology (ART) that can assist women to avoid passing mitochondrial DNA

disease to their biological child. This technology is not a cure for

mitochondrial disease but is rather a way to prevent children from inheriting

mitochondria that can cause mitochondrial disease.[2]

Under the current legislative framework, mitochondrial

donation is illegal under the Prohibition of Human Cloning for

Reproduction Act 2002 (Cth) and the Research Involving Human

Embryos Act 2002 (Cth). The Mitochondrial Donation Law Reform (Maeve’s

Law) Bill 2021 (the Bill) amends relevant Acts and associated Regulations to make

mitochondrial donation legal for research, training and human reproductive

purposes. The overall aim is for women at risk of passing on mitochondrial

disease to have reproductive options for biological children without the

increased risk of their child having mitochondrial disease.

Primarily the Bill makes changes to ensure that it is no

longer an offence to create, for the purposes of reproduction, and under

the relevant mitochondrial donation licences, a human embryo that:

- contains

the genetic material of more than two people and

- contains

heritable changes to the genome.

Given mitochondrial donation is a new medical technology, the

Bill introduces it in a staged and controlled manner with a two-stage implementation

approach. This is intended to allow for the expansion of scientific evidence to

ensure the techniques are safe and effective and undertaken in an ethically

appropriate manner.[3]

The Bill introduces five types of mitochondrial donation licences:

- a pre-clinical research and training licence

- a clinical trial research and training licence

-

a clinical trial licence

- a clinical practice research and training licence and

-

a clinical practice licence.

Initially, only three of the potential five licences will

be available from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). These

initial licences would authorise pre-clinical and clinical trial research and

training and clinical trial activities to take place. This would enable the

scientific evidence to continue to expand and would also allow ‘the safety,

efficacy and feasibility of mitochondrial donation for reducing the risk of

transmission of serious mitochondrial disease in humans’.[4]

The Bill contains provisions detailing what is authorised

under each of the mitochondrial donation licences, with provisions relating to

licence applications, conditions and administrative requirements. The licences

will be administered and regulated by the Embryo Research Licensing Committee of

the NHMRC (referred to in this Digest as the NHMRC Licensing Committee), with

dedicated provisions for the close vetting and oversight of applicants and

licence holders by the NHMRC.

Stage 2, which would permit mitochondrial donation in

clinical practice, is dependent on the success of the licenced techniques and

the findings of the Stage 1 review. As such, the two clinical practice related

licences are subject to further amendments to legislation before they can be

made available.

Whilst at the time of writing there has been limited

commentary since the introduction of the Bill, there have been robust

discussions through different consultation processes. Respondents have

primarily focussed on the ethical and social considerations and it has also

been widely noted that this is a new scientific technology. Due to the complex

and sensitive nature of the subject, people who have engaged with the

consultation processes appear to hold views that tend to be heavily skewed either

for or against.

In acknowledgement of the ethical issues and concerns raised

by the new technology endorsed by this Bill (including privacy, embryo creation

and destruction, consent and donor rights) the Minister for Health has stated

that the Bill will be put to a conscience vote.[5]

Purpose of the Bill

The purpose of the Mitochondrial

Donation Law Reform (Maeve's Law) Bill 2021 (the Bill) is to introduce mitochondrial donation techniques in a staged and

cautious approach, initially through research and a clinical trial. Following a

review of Stage 1, and further legislative changes, mitochondrial donation could

be made available in the clinical practice setting. Once more widely available

it is estimated that this technology could prevent 60 babies being born with

mitochondrial disease each year in Australia.[6]

The Bill:

- provides

for mitochondrial donation techniques to be administered under five types of

mitochondrial donation licences. Only three of the five licences would be

available in Stage 1, which would allow pre-clinical and clinical trial

research and training and clinical trial activities to take place

- provides

for the licences to be administered and regulated by the NHMRC Licensing

Committee

- sets

out provisions dealing with what is authorised under each of the five types of

mitochondrial donation licences, with strict conditions relating to licence

applications, conditions and administrative requirements. In addition, licence

holders would be subject to additional, and ongoing, requirements

- Stage

1 will allow eligible women to access mitochondrial donation by participating

in the clinical trial. It is anticipated that a low number of people will

access the technology, and the women who do participate, may require multiple

rounds of IVF. As such, the trial is expected to take place over approximately

10 to 12 years.[7]

The following legislation is engaged and amended to give

effect to the purpose of the Bill:

Structure of

the Bill

The Bill comprises a single schedule of three parts:

- Part

1 contains the main amendments to the PHCR Act, RIHE Act and

the RIHE Regulations.

- Items 4 and 5 of

the Bill makes the most significant amendments to the PHCR Act by

changing the legislation to ensure that it is no longer an offence to allow,

under a mitochondrial donation licence, the creation of an embryo with:

- the

genetic material of more than two people (item 4)

- changes

to its genome that would be heritable by the child’s descendants (item 5).

- Item 17 of the Bill makes the bulk of the amendments to the RIHE Actby adding proposed Division 4A

of Part 2, comprising of:

- Subdivision

A—Kinds of mitochondrial donation licences and what they authorise

- Subdivision

B—Applying for a mitochondrial donation licence

- Subdivision

C—Determining applications for mitochondrial donation licences

- Subdivision

D—Conditions of mitochondrial donation licences

- Subdivision

E—Ongoing requirements for holders of mitochondrial donation licences

- Subdivision

F—Variation, suspension, revocation and surrender

- Part

2 of the Bill contains other amendments to the PHCR Act, RIHE Act,

FOI Act, RIHE Regulations and the Therapeutic Goods (Excluded Goods)

Determination. These amendments will support the main amendments in Part 1.

- Part

3 of the Bill contains application and transitional provisions for the RIHE

Act and the RIHE Regulations.

A detailed explanation of Part 1 is

outlined on pages 4 and 5 of theExplanatory

Memorandum to the Bill.[8]

Background

Scientific background

Mitochondria

and mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondria are small DNA-containing structures found in

human cells. Mitochondria produce roughly 90 per cent of the energy our body

needs to function and also support a number of other functions.[9]

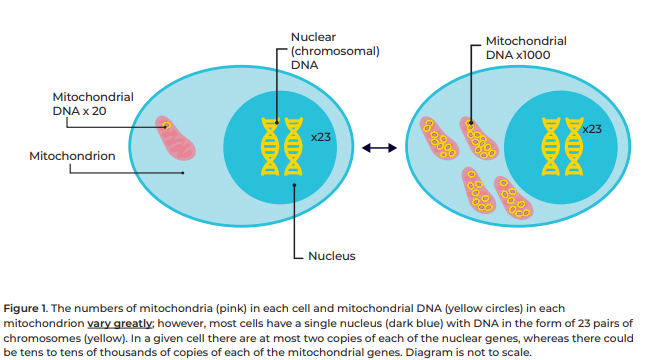

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

differs from nuclear DNA (nDNA) in a variety of ways, a few of which include:

- mtDNA

contains 37 genes, nDNA contains 20,000 to 30,000 genes

- mtDNA

is inherited primarily from the biological mother due to the mitochondria being

present in the mother’s egg cell,[10]

nDNA is inherited from both biological parents

- a

single cell can contain numerous mitochondria, and each of these can contain numerous

copies of mtDNA, a single copy of nDNA is contained in the nucleus of most cells

and there is usually just one nucleus per cell[11]

- mtDNA

has a much higher mutation rate than nDNA, estimated to be 100 times higher.[12]

Figure 1 below provides an illustration of nDNA and mtDNA

within a cell.

Figure 1: illustration of nDNA and mtDNA within a cell

Source: NHMRC, Mitochondrial donation issues paper: ethical and social

issues for community consultation,

NHMRC, [Canberra], [2019], p. 7.

Mitochondrial

DNA disease

Mitochondrial DNA disease refers to a mixed (heterogenous)

group of inherited conditions caused by mutations in mtDNA or nDNA that impact

the function of mitochondria (that is, reduce their ability to produce energy) and

can cause serious illness. This results in cell injury and death and can lead

to whole organ systems failing, which can be fatal.[13]

Currently, there is no known cure and treatment is mostly limited to the management

of symptoms.[14]

It is estimated that approximately:

- one

in 200 Australian babies are born with some level of mtDNA mutation that could lead

to mitochondrial DNA disease in their lifetime, although for many, the levels

of mutated mtDNA are too low to cause disease. This is estimated to be roughly

120,000 Australians[15]

- between

one in 5,000 and one in 10,000 Australians are estimated to develop severe or

life‑threatening mitochondrial DNA disease during their lifetime

- the

average lifespan of children born with mitochondrial DNA disease is estimated

to be between three and 12 years of age. However, the (symptomatic) onset of the

disease can affect people at any age and some individuals do not develop

symptoms until adulthood.[16]

[emphasis added]

Mitochondrial DNA disease can cause a lot of different

symptoms because mitochondria are located everywhere within the body. Due to

their role in energy production, the disease particularly affects organs that

have a higher energy use, such as the heart, muscles and brain. The proportion

of unhealthy mtDNA (referred to as mutation load) may affect the severity of the

mitochondrial DNA disease, for example, a low level of mutated mtDNA may mean

that a person does not exhibit any symptoms.[17]

Because one cell can contain many mitochondria, this can result in

heterogeneous mtDNA within the same cell. When the cell divides the

mitochondria are split between the two daughter cells in a random manner

(unlike nDNA).[18]

As a result, a cell can have a mix of healthy and unhealthy (or mutated) mtDNA

(see Figure 2).[19]

Figure 2: the mixed nature of healthy and mutated mtDNA within cells

Source: NHMRC, Mitochondrial donation issues paper, op. cit., p. 9.

For women who are heterogeneous carriers of mitochondrial

DNA disease (that is, they have both healthy and mutated mtDNA) it can be

difficult to predict the impact on a future child. This can leave people facing

difficult decisions on whether to have children and, if they do conceive, whether

to seek prenatal testing (if that is an option).[20]

Prenatal testing is discussed further under the ‘Treatment and prevention’ and

‘options for having children’ sections on pages 22–24.

Mitochondria

donation

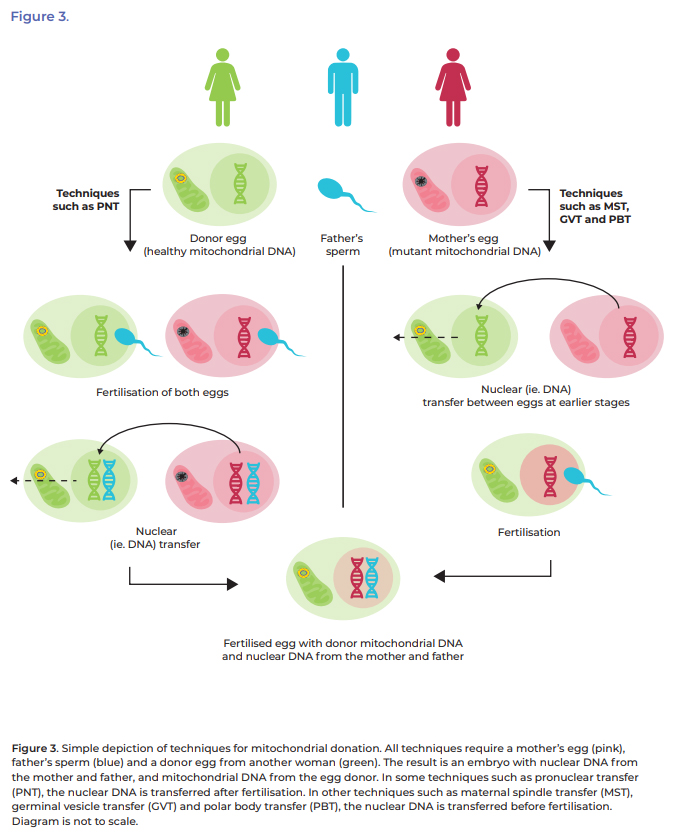

Mitochondrial donation is an assisted reproductive

technology (ART), involving in-vitro fertilisation (IVF).[21]

IVF refers to procedures where human eggs, sperm or embryos are handled outside

of the body (in-vitro) in order to establish a pregnancy.[22]

The purpose of mitochondrial donation is to reduce the risk of a child

inheriting mitochondrial DNA disease from a woman carrying the condition.[23]

This is achieved by creating an embryo using nDNA from the

prospective mother and father and healthy mtDNA from a donor. Several different

mitochondrial donation techniques can achieve this outcome, including:

- maternal

spindle transfer (MST)

- pronuclear

transfer (PNT)

- polar

body transfer (PBT) and

- germinal

vesicle transfer (GVT).[24]

Pages 42 and 43 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill provides

a detailed definition for each of these techniques.[25]

A simplified overview is given below in Figure 3.

Figure 3: simplified overview of mitochondrial donation techniques

Source: NHMRC, Mitochondrial donation issues paper, op. cit., p. 13.

Mitochondrial donation is a relatively new technology and

the long-term consequences are still unknown.[26]

Other options for having children are available to women that carry mtDNA

mutations, these are discussed further under the ‘Options for having children’

section on pages 22 to 24 of the Bills Digest.

It is important to note that mitochondrial donation cannot

cure existing mitochondrial DNA disease or prevent mitochondrial DNA disease

caused by mutations in nDNA. Estimates suggest mitochondrial donation may be

able to assist in the prevention of mitochondrial DNA disease in 60 births per

year in Australia.[27]

If mitochondrial donation becomes part of clinical practice in Australia, it is

expected that only a small number of women will access the technique.[28]

Policy background

Current legislation

RIHE Act

and PHCR Act

The Research Involving Human Embryos Act 2002 (RIHE Act) and the Prohibition

of Human Cloning Act 2002 were passed by Parliament in December 2002 in

response to community concerns, including ethical ones, about scientific

developments in relation to human reproduction and the use of human embryos. Both

Acts were amended in 2006 and the Prohibition of Human Cloning Act 2002 was

renamed the Prohibition of Human Cloning for Reproduction Act 2002 (PHCR

Act).[29]

The Acts establish a regulatory framework that prohibits

certain practices, including human cloning, and regulates the uses of excess

human embryos created through ART.[30]

Intergovernmental

agreement and state and territory legislation

In March 2004, the Council of Australian Governments

(COAG) agreed to the Research

Involving Human Embryos and Prohibition of Human Cloning for Reproductive

Purposes Intergovernmental Agreement (the IGA). The IGA creates a

nationally consistent scheme for the regulation of research involving human

embryos, the prohibition of human cloning and other unacceptable practices.[31]

Under the IGA all of the states and territories (other

than the Northern Territory) have introduced legislation that is consistent

with the Commonwealth’s RIHE Act and PHCR Act.[32]

Due to the staged approach and the way the Bill proposes introducing

mitochondrial donation, namely for very limited purposes restricted by the

proposed mitochondrial donation licences, the amendments introduced by the Bill

will not need to form any part of the nationally consistent scheme under the

IGA. This allows mitochondrial donation to be legalised under those limited circumstances

without corresponding amendments needing to be made to state or territory law

for Stage 1.[33]

International

policy

In 2015, the United Kingdom (UK) passed legislation to

legalise mitochondrial donation using the PNT and MST techniques. Prior to this,

the UK amended legislation to allow researchers to develop mitochondrial

donation techniques and conducted multiple reviews of the science as well as public

consultations on the social and ethical issues. To date, the UK is the only

country that has changed its laws and regulations to allow mitochondrial

donation.[34]

Despite being legal, access to mitochondrial donation in

the UK is tightly regulated, approved on a case-by-case basis and only approved

for patients at high risk of transmitting mutations that will lead to serious mitochondrial

DNA disease. At the time of writing, only one facility has been licenced to provide

mitochondrial donation, and the licence only allows for the use of PNT. As of

November 2020, it has been reported that up to 21 couples have attained a

licence to receive treatment and up to eight treatments have been approved. The

outcomes of these treatments have not been made publicly available for privacy

reasons.[35]

Other countries such as the United States, Singapore and

Sweden have released reports or conducted consultations regarding mitochondrial

donation, but legislation has remained unchanged. In countries that have no

specific government legal restrictions on mitochondrial donation techniques,

such as Mexico and Ukraine, there are reports of mitochondrial donation having

taken place.[36]

Australia’s

inquiry and consultations

Senate

Community Affairs Committee inquiry

In 2018, the Senate Community Affairs References Committee

(Senate Committee) undertook an inquiry into the Science of Mitochondrial Donation and Related Matters.

Among other things, the inquiry examined the impact of mitochondrial disease on

Australian families and the healthcare sector, the safety and efficacy of

existing donation techniques, and the ethical considerations.[37]

The Senate inquiry received 60 submissions and held one

public hearing. The Committee’s final report explores the experience of people

with mitochondrial DNA disease and their families, the science of mitochondrial

donation and the ethics and regulation of mitochondrial donation.[38]

The final report made four recommendations to Government:

- undertake

public consultation on the possible introduction of mitochondrial donation into

Australian clinical practice

- obtain

expert advice through the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)

about key scientific questions relating to mitochondrial donation

- engage

with state and territory governments on the findings of the inquiry and

- as

an interim measure, initiate dialogue with the relevant authorities in the UK

to facilitate access to the UK treatment facility for Australian patients seeking

mitochondrial donation.[39]

Governments

response to the Senate Committee’s report

The Government tabled a response to the Senate Committee’s

report in February 2019. The Government supported the Senate Committee’s

recommendations for expert advice and further consultation activities with the

Australian public and state and territory governments. Regarding opening a

dialogue with the UK for the potential access of Australians to their

mitochondrial donation services, the Government stated that it will reconsider this

recommendation following the consultation outcomes and expert advice.[40]

The Government tasked the NHMRC to establish a panel of

scientists and other experts to provide advice on the legal, regulatory,

scientific and ethical issues identified by the Senate inquiry. The work was

intended to develop the key questions to inform a community-wide consultation.[41]

NHMRC

Mitochondrial Donation Expert Working Committee

In March 2019, the NHMRC convened a Mitochondrial Donation

Expert Working Committee (NHMRC Expert Committee) to examine the questions posed

by the Senate Committee. In June 2020, the NHMRC Expert Committee statement

was released, reporting on three specific questions from the Senate inquiry.[42]

The Chair of the Expert Committee stated:

The Committee agreed that, given the complexity of the issues

raised, some disagreement was both to be expected and acceptable. As such, the

Expert Statement reflects the consensus view of the Committee on each question

as far as was possible.[43]

NHMRC

community consultations

Between September and November 2019, the NHMRC undertook

community consultation on the social and ethical considerations of the possible

introduction of mitochondrial donation in Australian clinical practice.[44]

The consultation process included:

- the

release of a Mitochondrial

Donation Issues Paper to support and inform the consultation process[45]

- a

citizens’ panel composed of ordinary citizens who engaged with mitochondrial

donation experts and stakeholders to learn more about the issues and develop a

position statement

- an

online submission portal to allow people to submit their written views on the

topic

- two

NHMRC hosted webinars discussing the topic

- public

forums held in Sydney and Melbourne and

- targeted

roundtable discussions for key stakeholders to present their views and discuss

perspectives.[46]

In June 2020, the NHMRC published the Community

Consultation Report that discussed the outcomes of the consultation

process.[47]

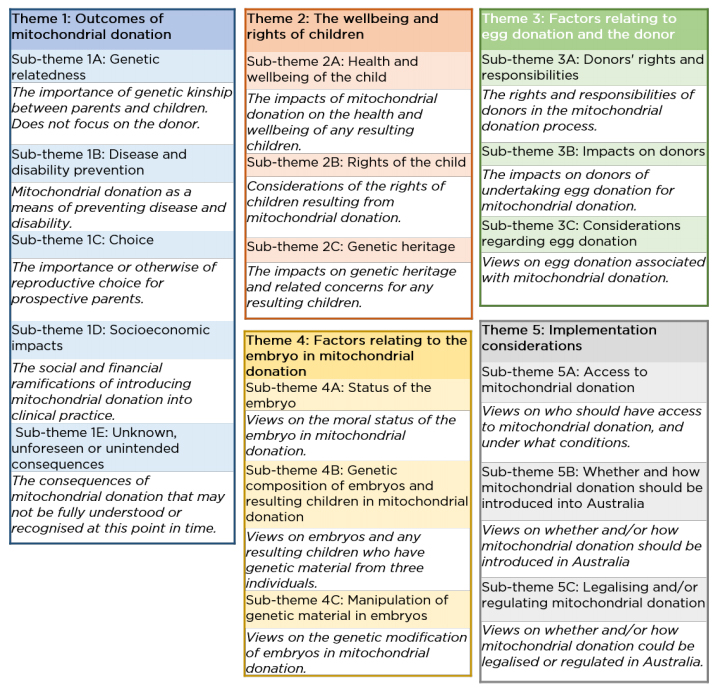

From the online submissions, the report identified five major themes, outlined below

in Figure 4.

Figure 4: outline of the themes from the community consultation online

submissions

Source: NHMRC, Mitochondrial donation community consultation report, NHMRC, 2020, p. 21.

The Community Consultation Report concluded:

It is clear that there is a range of opinions in the

community about mitochondrial donation, with a number of respondents being

passionately opposed to its introduction while others are supportive. This

range of views must be taken into consideration in any future work on this

issue.[48]

Department

of Health consultation

The Minister for Health announced, on 5 February 2021,

that the Department of Health (DoH) had commenced a consultation process on a proposal to

introduce mitochondrial donation using a two-stage process (discussed further

below).[49]

The public consultation took place from 5 February 2021 to 15 March

2021 and received 74 survey responses and 27 written submissions. The DoH released

its Consultation Summary Report on 22 March

2021. The report found that the majority of the feedback reflected the responses

provided through the Senate inquiry and NHMRC consultation process.[50]

Embryo

research licensing

The PHCR Act and the RIHE Act establish a

regulatory framework around research and the creation, and use of human embryos

through ART. The RIHE Act and the PHCR Act outline arrangements

between the Commonwealth and the states and territories. Both Acts prohibit

particular activities while identifying some activities that can only be

undertaken if authorised by a licence.

The NHMRC Licensing Committee is a Principal Committee of

the NHMRC and is established under Division 3 of Part 2 of the RIHE Act. It

is responsible for overseeing the RIHE Act and the PHCR Act.[51]

To undertake research on human embryos, including use of excess ART embryos and

research and training involving fertilisation, the researcher must operate

under the approved activities of a licence issued by the NHMRC Licensing

Committee.[52]

Tabling of

Reports

The RIHE Act requires the NHMRC Licensing Committee

to table reports to either House of Parliament twice a year, upon request or at

its discretion, about the operation of the Act and the licences issued.[53]

Maintaining

a Licence Database

Section 29 of the RIHE Act requires the NHMRC

Licensing Committee to maintain a public database on each licence, including

information on:

- the

name of the licence holder

- the

number of excess ART embryos or human eggs authorised for use by the licence

- a

short statement of the nature of use of these excess embryos or eggs, and

creation or uses of other embryos, authorised by the licence.[54]

Regulation

of Excess ART Embryos

Part 2 of the RIHE Act regulates the use of excess

ART embryos, other embryos and human eggs. Section 9 provides the following

definition of excess embryos for this Part:

excess ART embryo means

a human embryo that:

- was

created, by assisted reproductive technology, for use in the assisted

reproductive technology treatment of a woman; and

- is excess to the needs

of:

- the woman for whom it was

created; and

- her spouse (if any) at

the time the embryo was created.

(2) For

the purposes of paragraph (b) of the definition of excess

ART embryo, a human embryo is excess to the needs of the persons

mentioned in that paragraph at a particular time if:

- each such person has given written authority for use of the embryo for a purpose other than a purpose relating to the assisted reproductive technology treatment of the woman concerned, and the authority is in force at that time; or

- each such person has determined in writing that the embryo is excess to their needs, and the determination is in force at that time.[55]

Human

Research Ethics Committees

In considering a licence application, the NHMRC Licensing

Committee must be satisfied of a number of criteria, including the proposed

project/activities having been assessed and approved by a Human Research Ethics

Committee (HREC).[56]

Research institutions, such as hospitals and universities, have a HREC that reviews

all research proposals that would involve human participants to ensure the

proposed work is ethically acceptable. The NHMRC has published the National

Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (National Statement), which

sets out the requirements of a HREC and the researchers.[57]

Proposed

two-stage process

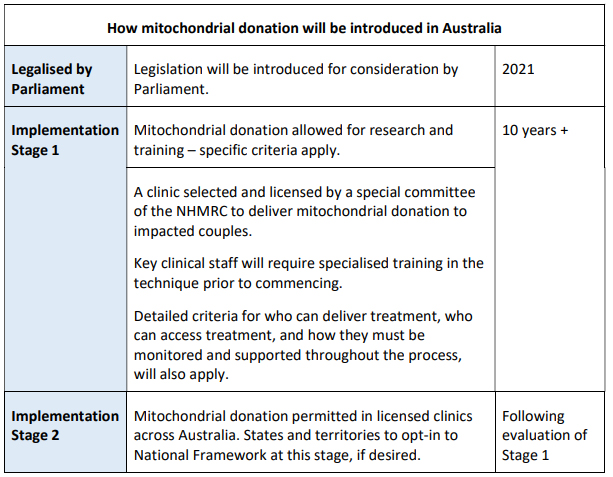

The introduction of mitochondrial donation in Australia

has been framed as a two-stage implementation process. The two-stage approach

intends to provide a way for the mitochondrial donation technology and

procedures to be introduced cautiously, with time allowed to gather evidence on

the safety, efficacy and clinical utility of the techniques.[58]

A brief overview of the two-stage approach is provided in Table

1 below.

Table 1: proposed two-stage process for the introduction of mitochondrial

donation

Source: DoH,

Legalising Mitochondrial Donation in Australia: Public

Consultation Paper, DoH, [Canberra],

[2021], p. 5.

Stage

1—research, training and clinical trials

It is proposed that Stage 1 would include:

- an

expansion of the role and remit of the NHMRC Licensing Committee to include

licensing and oversight of specific mitochondrial donation licences

- the

NHMRC Licensing Committee developing the administrative requirements and

assessment procedures for individuals and organisations applying for one of the

following three licence types which permit mitochondrial donation in Australia:

- pre-clinical research and training licence

- clinical

trial research and training licence and

- clinical

trial licence

- the

NHMRC Licensing Committee and the NHMRC developing monitoring processes for

licence holders

- the

DoH running a competitive grants process to identify a suitable organisation to

undertake the clinical trial

- this

trial is anticipated to take approximately 10 years, as the number of

participants is expected to be low and each participant may require multiple

IVF procedures before a successful pregnancy is achieved.[59]

Transition

from Stage 1 to Stage 2

To facilitate the transition to Stage 2, the Bill amends

the PHCR Act and the RIHE Act to establish all five licences,

including the two clinical practice related licences. However, organisations

will not be able to apply to the NHMRC Licensing Committee for either of the

two clinical practice licences until a particular technique is specified in the

RIHE Regulations for this purpose. The permitted

mitochondrial donation techniques for clinical practice will not be authorised

until Stage 1 is completed and the safety and efficacy of the techniques have

been demonstrated.[60]

The states and territories are responsible for the

regulation of ART in their jurisdiction. When undertaken in a clinical practice

setting, mitochondrial donation is expected to be categorised as an assisted

reproductive technology. If Stage 2 goes ahead, mitochondrial donation for the

purposes of clinical practice will not be able to occur in a state or territory

until the relevant state or territory legislation is amended to allow it.[61]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum of the Bill, the

transition to Stage 2, and the specification of the permitted techniques in the

Regulations, will be decided by the Government following consideration of the

progress and outcomes of Stage 1, and other expert advice.[62]

Stage

2—clinical practice

Under Stage 2, it is proposed that:

- jurisdictions

may choose to be part of a national regulatory framework, which will allow for

licenced clinical practice, in participating states or territories

- as

part of the regulatory scheme, the following two licences, to be overseen by

the NHMRC Licensing Committee, would be available:

- the

clinical practice research and training licence and

- the

clinical practice licence.[63]

Ethical and

social considerations

This Bill will be put to a conscience vote.[64]

The Minister for Health outlined the reasoning behind this decision in his

second reading speech:

Some members of the community … have raised concerns about

issues such as privacy of parents and children, creation and destruction of

embryos, ensuring informed consent, donor rights and the newness of the

science. I acknowledge that not all members of the community are comfortable

with the use of this technology, and that's reflected in the free vote—the

ability to vote with conscience—that has been called for jointly by the major

parties.[65]

The NHMRC Expert Committee Issues Paper states:

In addition to questions around safety and effectiveness,

scientists, researchers and others have identified ethical and social issues

that arise from the use of mitochondrial donation in research and in clinical

treatment. These include the rights of the child, the status of the embryo, the

role and rights of women donating eggs, and community considerations.[66]

It is these considerations that appear repeatedly in the submissions

and reports from the Senate inquiry, the NHMRC community consultation

activities and in the summary report on the most recent consultation undertaken

by the DoH. These are complex and complicated issues and ones that people have

strong and opposing views on. This section briefly summarises some of the key ethical

and social considerations raised in the different consultation undertaken.

Treatment

and prevention

There is no cure for mitochondrial disease and no single

treatment option, instead treatment is tailored to the individual.[67]

It is estimated that approximately one in every 200 children born in Australia has

some level of mutation in their mitochondria with between one in 5,000 and one

in 10,000 Australians developing severe mitochondrial disease.[68]

In 2006 a paper was released in The Lancet that suggested that at

least 3,500 women in the UK, most of child-bearing age, were likely to be

carriers of mtDNA mutations which could be passed on to their children,

potentially causing mitochondrial disease.[69]

A review undertaken in 2012 provided some additional context on the estimated

figures for the UK:

However, bearing in mind the limiting factors listed above, a

widely-quoted figure (approximated from different published papers) is that

around one in 6,500 children is thought to develop a more serious mitochondrial

disorder, where some of these disorders can be fatal. In the context of

neuromuscular disease, this figure would make mtDNA disorders one of the most

common inherited neuromuscular disorders.[70]

In a submission to the Senate inquiry in 2018, Professor

Christodoulou, a clinical geneticist, stated:

There are currently very few effective treatments for this

group of disorders, and so prevention is the main approach that can be

currently offered to families. For nuclear-encoded gene mutations traditional

prenatal testing or pre-implantation genetic diagnosis techniques are very

effective and have a long and established track record. However, apart from a

few specific exceptions, for primary mitochondrial DNA disorders these

approaches are generally not as definitive for a number of reasons. It is for

this latter group of disorders where mitochondrial donation is particularly

relevant.[71]

In the NHMRC community consultation, concerns were raised,

including by people with mitochondrial disease, that the introduction of

mitochondrial donation could have negative impacts and could exacerbate

‘negative social perceptions and treatment of people with a disability’.[72]

Options for

having children

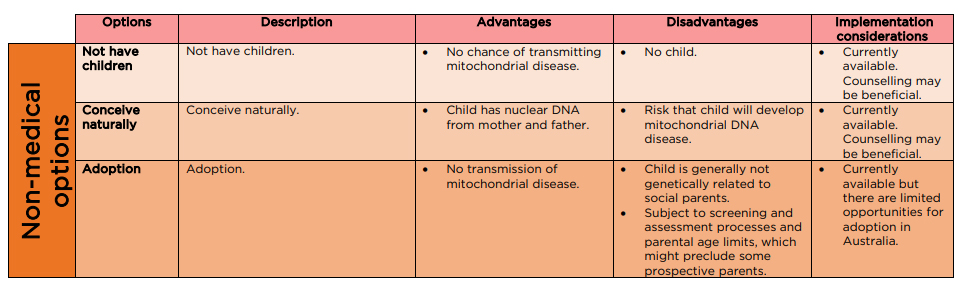

There are three main non-medical options available for perspective

parent/s who are at increased risk of passing on mtDNA mutations that could

cause mitochondrial disease (see Figure 5):

- adoption

- fostering

and

- natural

conception.[73]

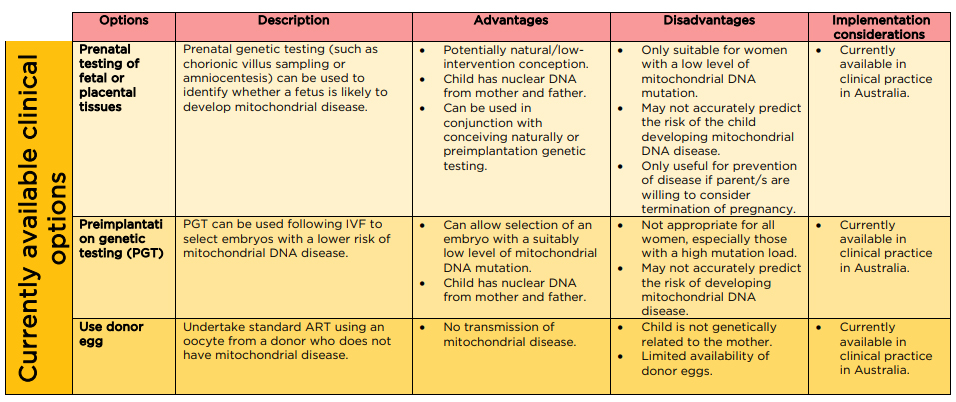

There are also three main medical options currently

available (see Figure 6):

- prenatal

testing

- pre-implementation

genetic testing and

- use

of a donor egg.[74]

As identified in Figures 5 and 6 below, there are advantages

and disadvantages for all options, including some medical options not being clinically

appropriate for all women. According to the Senate Committee’s final report, some

submissions that did not support mitochondrial donation argued in favour of non-genetic

options.[75]

For some people, having a child who is genetically related

to them is extremely important but this desire is not always considered a

compelling enough reason to introduce mitochondrial donation by people and

organisations who made submissions to the NHMRC and Senate inquiry.[76]

In the (US) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)

report on the ethical, social and policy considerations of mitochondrial

donation, the authors conclude that the current options available achieve some

of the desirable attributes of mitochondrial donation but not all of them.[77]

The Senate Committee expressed the view that it is ‘desirable for governments

to support fertility treatment as a social good’ but this is not an unlimited

responsibility and any treatments should be provided equitably.[78]

The range of options available, which may include

mitochondrial donation, provide people with different choices, with some

options appealing to some people and not others. Importantly, for people to

make these choices, they need readily available access to appropriate

information and support to assist them in making their decisions.

Figure 5: current non-medical reproductive options for women where there is a

risk of transmitting mitochondrial disease to offspring

Source: NHMRC Mitochondrial Donation Expert Working Committee, Expert

Statement, NHMRC, [Canberra], 2020, p. 66.

Figure 6: current reproductive options for women where there is a risk of

transmitting mitochondrial disease to offspring

Source: NHMRC Mitochondrial

Donation Expert Working Committee, Expert statement, NHMRC, [Canberra], 2020, p. 67.

Use of new

techniques

As outlined in the scientific background, research on the safety

and efficacy of mitochondrial donation techniques is continuing with new

evidence emerging and with knowledge gaps remaining. Through the community

consultation process undertaken by the NHMRC, the unknown, unforeseen or

unintended consequences were considerations identified in submissions for proponents

and opponents of mitochondrial donation.[79]

Sex

selection

Sex selection through the use of ART is permitted in

Australia but is an option reserved for cases that would reduce the risk of

transmission of a genetic condition or disease that would severely impact the

person’s quality of life.[80]

Sex selection for male embryos with mitochondrial donation is considered for

two different reasons.

As outlined in the Senate inquiry, some experts have

suggested the children from women who were themselves born using a

mitochondrial donation technique may have an additional risk of developing

mitochondrial disease than the children of men born using mitochondrial

donation due to mtDNA carryover.[81]

Sex selection is also raised in consideration of inheritable

genetic modifications. As outlined in the scientific background, mtDNA is

inherited almost exclusively through the maternal line. Therefore, if a man was

born using mitochondrial donation, any child he would have would inherit the

mother’s mtDNA and not his mtDNA. As such, the changes to his mtDNA will not be

passed on to the next generation.

In the NASEM report, it is recommended that mitochondrial

donation be limited to male embryos in the first instance to avoid heritable

genetic modifications. The authors argue this position is not about the

acceptability of sex selection and is rather based on the need to proceed slowly

and prevent potential adverse heritable changes being passed to future

generations.[82]

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics, based in the UK, raise concerns about the use

of sex selection with mitochondrial donation and provide the following extract

from a submission it received during its consultation:

In suggesting that only males be conceived initially, there

is an underlying assumption that the unknown long-term adverse consequences

would relate only to the mitochondria (passed to the next generation through

eggs, not sperm). As this may not be the case, there is no justification for

limiting the risk to one particular sex. No technique for the eradication of

disease should be permitted until there is reasonable evidence for its safety.

We would not argue that experimental treatments should not be permitted in

medicine, however… if such a course of action as selecting only males needs to

be considered, it implies that at the time of offering the treatment too little

is known about its safety. Another implication is that should sex selection be

permitted the boys born from such treatment would live with uncertainty about

their future health, beyond that normally experienced. The potential

psychological implications of this would need to be included in pre-treatment

counselling of the couples.[83]

The potential for sex selection was identified in the

Senate inquiry, with a number of scientific witnesses being of the opinion that

there was no clear justification for sex selection for male embryos if

mitochondrial donation was introduced in Australia.[84]

This issue was also considered by the NHMRC Expert Committee who reflected that

restricting mitochondrial donation to male embryos would introduce its own problematic

ethical, scientific and practical considerations.[85]

Status of

the embryo

As noted in the NHMRC community consultation report, broader

concerns about ART and the status of the embryo featured in many submissions it

received as ‘for many people, it is not possible to separate the different

technologies and issues related to embryos …’[86]

These concerns were also identified in submissions made to the Senate inquiry. Therefore,

this issue is briefly touched on, noting it does not only relate to

mitochondrial donation.

Submissions received by both the Senate inquiry and the

NHMRC raise concerns about the creation of embryos for techniques that may not

use the whole embryo and as such, part of the embryo will be disposed of (as

with PNT), or not using the embryos for reproductive purposes. A number of

submissions to the Senate inquiry reflected on the moral status of the embryos.

Some submissions expressed their view on the inherent dignity of the embryo

(and sometimes at earlier development stages, such as the zygote) which must be

respected and that embryos should not be treated as a means to an end.[87]

In contrast, some submissions received by the NHMRC

community consultation process acknowledged that embryos would be destroyed as

part of mitochondrial donation but respondents did not necessarily consider

this unethical.[88]

The rights

and wellbeing of the child

The health and wellbeing of people born from mitochondrial

donation are important factors to be considered, especially given some of the

health risks associated with the technology are still unknown.[89]

There is no way to obtain the views of a child that would

be born using mitochondrial donation. The following is an extract from the

Senate inquiry’s report on the science of mitochondrial donation and related

matters relating to the issue of whether a child would have consented to

mitochondrial donation:

People who live with a mitochondrial disease and their

children had little difficulty imagining whether a person who was born from a

mitochondrial donation technique would consent. Mary, a person living with a

mitochondrial disease, asked her children whether they thought they would have

consented to the procedure:

In the process of preparing my

submission, I talked to my children about this and I said to them: 'What do you

think?' They said, 'If we had a child with mitochondrial disease, we would love

that child we would understand what the child was going through.' But their

view was that everyone who has mitochondrial disease, their families that are

affected by it, should have this choice.

Justin, who also lives with a mitochondrial disease, told the

committee that he believes that a child who was born of the technique would

understand the choice that had been made for them:

What I have learned over the last

2½ years is that having a disability or a sickness like we've got is about

compromise. You are compromising the whole time about what you used to have in

your life that you don't have anymore. Being part of a family where the other

members of the family are disabled or are sick and is also about compromise—you

can't do the things you need to do. So I'm confident that any child, if this

technology was to go forward, born through mitochondrial donation would

understand that life is about compromises when you are in this situation. If

that means that I can't participate in recreational genetics, if that means

that a second woman gave me the slightest part of my DNA, I think that would be

a compromise I would be able to live with.[90]

[references removed]

It is also not possible to identify how a child born using

mitochondrial donation would feel about the donor (or how the donor may feel

about the child), with this potentially depending on the individuals involved

and their unique situations.[91]

In response to the NHMRC consultation, many submissions raised questions about whether

the child would be able to access information about the donor, with some people

considering it important that the child be able to do so.[92]

The privacy of the child and their family is another

consideration that is raised repeatedly. Respondents to the NHMRC community

consultation raised the need to avoid ‘medicalising’ the child but also the

need for additional information about the safety and efficacy of mitochondrial

donation.[93]

The donor

Different considerations and concerns have been raised in relation

to the donor, one of the most common ones being the idea of a child with three

parents. In the Senate inquiry, the main question this point prompted was whether

a mtDNA donor should be considered a parent.[94]

This question can be considered in two different ways:

from a genetic perspective and from a social one. With regards to genetic

contribution, several submissions and witnesses flagged the proportion of the

genetic material that the mtDNA contributes (0.1 per cent) and the role of the mtDNA.

From a social perspective, some think that the mtDNA donor can be considered

equivalent to an organ or tissue donor.[95]

For some people, organ and tissue donation is accepted and acceptable medical

practice but for others, this is not the case. One of the concerns raised about

donation is that it can impact the identity of the recipient, including, but

not limited to, the adoption of some of the traits of the donor.[96]

Whilst these concerns are not unique to mitochondrial donation, they may still

impact some people’s views on it. The Senate Committee concluded that

mitochondrial donation would not lead to a child having three parents and mtDNA

donation should be conceptualised as being similar to organ donation.[97]

In considering the donor, as is the situation with egg

donation in general, robust processes will need to be implemented to ensure

informed consent and address potential issues like coercion. In addition, harm

minimisation and respect will also need to be considered.[98]

In the NHMRC community consultation, the donor’s right to confidentiality or

even anonymity was raised as an important consideration, with submissions

suggesting donors should be able to be anonymous and other submissions stating

that donors should be identifiable.[99]

Committee

consideration

Senate Standing

Committee for Selection of Bills

At its meeting on 13 May 2021, the Senate Standing Committee

for the Selection of Bills deferred consideration of the Bill to its next

meeting.[100]

Senate

Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

The Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills

(the Committee) reported on this Bill on 21 April 2021.[101]

The Committee’s concerns largely arose from significant matters within the Bill

being assigned to delegated legislation.[102]

Mitochondrial

donation licence application fee

The Committee expressed concerns regarding proposed

paragraph 28H(7)(d), which provides that an application for a

mitochondrial donation licence must be accompanied by a fee, if any, prescribed

by the Regulations. The Committee questioned why the fee-making power is to be

determined by delegated legislation and why the Bill, and the Explanatory Memorandum

for the Bill, contained no information or guidance on how the fee will be calculated,

any cap on the maximum fee amount or, how to ensure that the fee will be

necessary and appropriate.[103]

The Committee considered that, at a minimum, the Bill

should include a provision stating that the fee must not be such as to amount

to taxation, noting the advice set out in paragraph 24 of the Office of

Parliamentary Counsel Drafting Direction No. 3.1.[104]

The Committee requested further advice from the Minister,

including:

- how

the amount of any fee charged will be calculated and how it will be ensured

that a fee charged to a person will be necessary and appropriate and

- whether

the Bill can be amended to provide at least high-level guidance regarding how

fees will be calculated, including, at a minimum, a provision stating that the

fee must not be such as to amount to taxation.[105]

Definition

of ‘proper consent’ and provision for withdrawal of consent

The Committee expressed concerns regarding proposed

subsection 28N(8) and proposed subsection 24(9), which provide for

the definition of 'proper consent' concerning the use of a human egg or a human

sperm for Division 4A of Part 2 and 'proper consent' concerning the use of an

excess ART embryo or a human egg for Division 4 of Part 2, respectively. Both

of these proposed subsections refer to the definition of ‘proper

consent’ as consent that is obtained under guidelines issued by the CEO of the NHMRC

under the National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992 and

prescribed by the Regulations.[106]

The Committee also expressed concerns regarding proposed

subsection 28N(9) which provides that the Regulations may provide in

relation to the withdrawal of consent, including that consent cannot be

withdrawn in certain circumstances.[107]

The Committee questioned why significant matters, such as

provisions defining key terms as well as requirements relating to the

withdrawal of consent, are not included in the primary legislation. The

Committee acknowledged the justification, in the Explanatory Memorandum for the

Bill, for the use of delegated legislation regarding item 105 of the

Bill, but questioned why the justification did not cover proposed

subsections 28N(8) and (9) and proposed subsection 24(9).[108]

The Committee expressed general concern regarding provisions

in a Bill that allow for the incorporation of legislative provisions by

reference to other documents because such an approach:

- raises the prospect of changes being made to the law in the

absence of parliamentary scrutiny, (for example, where an external document is

incorporated as in force 'from time to time' as it is here this would mean that

any future changes to that document would operate to change the law without any

involvement from Parliament);

- can create uncertainty in the law; and

- means that those obliged to obey the law may have

inadequate access to its terms (in particular, the committee will be concerned

where relevant information, including standards, accounting principles or

industry databases, is not publicly available or is available only if a fee is

paid).[109]

The Committee requested further advice from the Minister,

including:

- why

it is considered necessary and appropriate to leave provisions defining the

scope of the term ‘proper consent’ (proposed paragraph 28N(8)(b) and proposed

subsection 24(9)) and requirements relating to the withdrawal of consent (proposed

subsection 28N(9) to delegated legislation

- whether

the Bill can be amended to include at least high-level guidance regarding these

matters on the face of the primary legislation

- why

it is considered necessary and appropriate to apply the ART Guidelines as in

force or existing from time to time (noting that this means that future changes

to the guidelines and therefore the definition of ‘proper consent’ will be

incorporated into the law without any parliamentary scrutiny) and

- whether

the Bill could be amended to provide for the meaning of 'proper consent' on the

face of the instrument or the Bill, rather than relying on the incorporation of

the ART Guidelines.[110]

Privacy

The Committee expressed concerns regarding proposed

section 28R(1)(e) and proposed section 28R(3)(d), which provides

that the Regulations may prescribe information that the holder of a clinical

trial licence or a clinical practice licence must collect for a donor, or a

child born as a result of mitochondrial donation. The Committee noted that the

Regulations (as a legislative instrument) are not subject to the full range of

parliamentary scrutiny and questioned why significant matters, such as the

collection of personal information, is not included in the primary legislation.

[111]

The Committee acknowledged the justification made in the Explanatory

Memorandum of the Bill, that delegating the collection powers to the

legislative instrument maintains administrative flexibility and is consistent

with state ART laws, but did not accept the justification to be sufficient.[112]

The Committee requested further advice from the Minister,

including:

- why

it is considered necessary and appropriate to leave the scope of sensitive

information-collection powers to delegated legislation and

- whether

the Bill can be amended to include further guidance regarding these matters on

the face of the primary legislation.[113]

The Minister’s response was received by the Committee on

10 May 2021 but had not been published at the time of writing.[114]

Policy

position of non-government parties/independents

Due to the complex nature of the Bill, the Cabinet, the Party

Room and the Opposition have agreed to allow a conscience vote, meaning members

of Parliament are not obliged to follow their party line, but can vote

according to their own moral, political, religious, or social beliefs.[115]

ALP

During the Bill’s second reading speech the Minister for

Health, Greg Hunt, stated that that the Opposition supports the Bill:

That's why, as a minister, as a father and as an individual;

with the passionate support of the Prime Minister, who is patron of the Mito

Foundation, publicly and proudly; with the support of the opposition—and Chris

Bowen has been a champion in supporting this and has passed that baton to his

successor, Mark Butler; with the support of the community; and with the support

of people such as Sarah and Joel Hood, and Catherine McGovern from the

foundation, we seek to avoid the heartache, pain and anguish of having a child

with severe mitochondrial disease.[116]

This is supported by an article reporting the then Shadow

Minister for Health, Chris Bowen, advising that Labor will support changing the

laws to allow for mitochondrial donation.[117]

In a speech in 2020, Mr Bowen stated he has had conversations with the Minister

for Health on the best way to jointly manage the process of a mature,

non-partisan debate in Parliament about the next steps needed to tackle

mitochondrial DNA disease, including mitochondrial donation.[118]

Following the second reading speech of the Bill, Labor MP Catherine

King commended the Minister for Health on the work he has done for the Bill and

acknowledged that, whilst mitochondrial donation is a difficult issue, it is

incredibly important.[119]

In September 2020, Labor MP Dr Andrew Leigh, conducted an

online and a face-to-face forum with his constituents to discuss and listen to

their views on mitochondrial donation.[120]

When asked if he already had a view on the legalisation of mitochondrial

donation, Dr Leigh stated: ‘My vote will be guided by the process, not bound.’[121]

Since the public forums, he has not offered any further views on mitochondrial

donation.

In 2019, during Private Members’ Business, Labor MP Dr Mike

Freelander spoke on the importance of legislating for mitochondrial donation.[122]

While not explicitly stating her support for the legalisation

of mitochondrial donation, during the tabling of the report prepared by the Senate

Committee inquiry in 2018, Labor Senator Louise Pratt, a member of the

Committee, reiterated her support for the report and stressed the importance of

examining the laws to see if they should be amended.[123]

The Greens

At the time of writing, only one member of the Australian

Greens had commented on their position regarding the legalisation of

mitochondrial donation. During the tabling of the report prepared by the Senate

Committee inquiry in 2018, Senator Rachel Siewert, who was Chair of the

Committee, stated:

There's no doubt in my mind that this mitochondrial donation

has a very strong potential for helping those families who are affected by

mitochondrial DNA where the disease is inherited. There's no doubt in my mind

that this has potential. But there are some things that need to occur if this

type of donation technique is to occur. There is also no doubt in my mind that

it would help affected people and those who have genetically linked children.

It would certainly help.[124]

Minor

parties and independents

At the time of writing, none of the other

minor parties or independents had formally stated a position on the Bill.

Position of

major interest groups

At the time of writing, the Mito Foundation had welcomed

the Bill but did not comment on any specific component. No other commentary on

the Bill had been identified from other interest groups.[125]

However, different groups have expressed broader views on legalising

mitochondrial donation in Australia over the course of the consultation

processes undertaken by the Senate inquiry, the NHMRC and the DoH. The

following section provides an overview of key elements raised by interested

group through the Senate inquiry. Respondents considered a number of questions

posed by the Senate Committee and provided feedback from a range of

perspectives, including responses from:

- people

with mitochondrial disease and their families

- scientists

- people

providing clinical services (for example, clinical genetics and assisted

reproduction)

- ethicists

and religious organisations.

As previously noted, these are complex and complicated

issues on which it is perhaps not possible to reach an agreed position. The

submissions included in the following section have been selected to illustrate

the range of commentary rather than nominating ‘major interest groups’ only. Not

all submissions to the Senate inquiry have been included in the following discussion,

but they are available on the Senate inquiry webpage.[126]

It should be noted that the submissions are a few years old and some positions

discussed below are also raised in the previous section on ethical and social

consideration.

Senate Community Affairs References Committee Inquiry

into: The Science of Mitochondrial Donation and Related Matters

There are

few effective treatments and no cures

In its submission to the Senate inquiry, the Mito Foundation

(the Australian Mitochondrial Disease Foundation) raised the issue that ‘there

are few effective treatments and no cures for mitochondrial disease’.[127]

The Human Genetics Society of Australasia (HGSA) noted the

importance of not over-hyping the potential of mitochondrial donation as it is

not ‘life saving’ or a ‘magic bullet’ as it does not save the life of a person

born with mitochondrial disease nor does it cure all mitochondrial DNA disease.[128]

The Mito Foundation noted this point in its supplementary submission and draws

attention to the similarities with disease prevention and health promotion

approaches.[129]

In its submission, the Australian Catholic Bishops

Conference (ACBC) raised concerns about dedicating resources to mitochondrial

donation as it does not help people who already have mitochondrial disease. The

ACBC also stated that there is a risk that this could imply people with

mitochondrial disease have lives of less worth than others.[130]

Current

reproductive options

The Mito Foundation noted in its submission that people

are choosing to remain childless to avoid the risk of their child having

mitochondrial disease. It goes on to state that mitochondrial donation is the

only option for some people with a mtDNA disorder to have children who are

genetically related to them and will not inherit mitochondrial DNA disease.[131]

The HGSA noted the emotional impact that mitochondrial

disease can have, stating the ‘clinical experience of HGSA members suggests

that mothers who have transmitted these disorders are often plagued with guilt

as there is a lack of effective treatments…’.[132]

The ACBC is of the opinion that ART is not in the best

interest of prospective parents, or their potential children, as it raises

issues affecting the dignity of all the parents and children. Instead of using

ART, ACBC identified several alternative reproductive options, noting none of

these options ‘are easy and go against the strong human desire for genetically-related

children’.[133]

Scientific

considerations

The Mito Foundation pointed out that the risks and

benefits of IVF are well known, including that it is not 100 per cent effective

or safe. It supported the introduction of mitochondrial donation in Australia

being limited to institutions and clinics with staff with demonstrated

expertise in embryology and IVF.[134]

In its submission, the HGSA stated it is ‘not aware of any

evidence to suggest that there would be significant risks to the children who

would be born following mitochondrial donation’.[135]

The Fertility Society of Australia (FSA) echoed this view, stating that ‘it

would appear that the balance of risk versus benefit in this debilitating

disease is now at a point where [mitochondrial donation] should occur’.[136]

The Biomedical Ethics Research

Group from the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute (MCRI) acknowledged the

safety concerns justifying a cautious implementation but noted that these

concerns should not legally prohibit the introduction of mitochondrial

donation.[137]

Ethical

considerations

The Mito Foundation raised concerns that failure to

introduce mitochondrial donation in Australia may result in some people

exploring fertility tourism options.[138]

In responding to certain considerations raised about egg donors, the Mito

Foundation noted that egg donation is voluntary in Australia and therefore did

not agree with concerns about the donor experience reducing the validity of

mitochondrial donation.[139]

The FSA argued that there is an ethical obligation to use a technology that

could avoid people having a disabling or fatal illness or condition.[140]

The Biomedical Ethics Research Group from the MCRI stated that there is ongoing

debate in the bioethics literature on the moral significance, if there is any,

of mitochondrial DNA and genetic connectedness.[141]

The ACBC raised several ethical concerns about

mitochondrial donation, including that PNT is a form of human cloning (due to

the transfer of nDNA) and the use of genetic material from more than two people

would threaten the rights of a child to inherit their relationship to natural

parents.[142]

The Plunkett Centre for Ethics raised similar ethical concerns about

mitochondrial donation to the ACBC and also suggested that introduction of

mitochondrial donation would open the door ‘to eugenic germ-line genetic

manipulation’.[143]

Both the ACBC and the Plunkett Centre for Ethics raised concerns about the

language ‘mitochondrial donation’ being misleading as, with some of the

techniques, the nDNA is moved rather than the mtDNA.[144]

Legal

considerations

The Australian Academy of Science recommended Australia

introduce mitochondrial donation techniques into clinical use and research,

similar to the approach taken in the UK, with due diligence of regulation and

oversight.[145]

This position is supported by the FSA and HGSA, with the HGSA strongly

advocating for a flexible and responsive governance system to minimise unintended

consequences experienced with the existing regulation.[146]

Financial

considerations

Using the Impact Statement of The Human Fertilisation and

Embryology (Mitochondrial Donation) Regulations 2015 (UK), the Mito Foundation

suggested that the introduction of mitochondrial donation could deliver a net

benefit of approximately $61 million (AUD) per year and $575 million (AUD) over

ten years.[147]

It also provided an estimate that a National Disability Insurance Scheme plan

may fund up to $120,000 per month for a child with mitochondrial disease.[148]

The Biomedical Ethics Research Group from the MCRI presented

an ethical argument on finite resources, suggesting that treating one person

with an expensive treatment can reduce the resources available for other people.

Therefore, allowing mitochondrial donation to prevent mitochondrial disease

would benefit others by increasing available capacity in the health system.[149]

The ACBC stated that given its ethical and risk related concerns, it does not

support the use of the limited resources available in both health and research for

the introduction of mitochondrial donation.[150]

Financial

implications

The Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill states that there

will be no net financial impact arising from the implementation of the Bill, and further explains:

Following the passage of the legislation, it is anticipated

that there will be some additional costs associated with establishing new

administrative processes for receiving and processing applications for and

issuing of the new mitochondrial donation licences. There will also be some

ongoing costs to Government associated with providing:

-

ongoing support for the ERLC and for ongoing compliance monitoring

related to the new licences

-

ongoing project management and support for any Commonwealth funded

clinical trial of mitochondrial donation, and

-

the establishment and maintenance of new data systems.

However, as these activities will be undertaken as an

extension of already established Government processes, the ongoing costs are

anticipated to be minimal and will be offset within the Department of Health

portfolio. In addition, whilst it is not possible to accurately predict, it is

anticipated that ten or fewer mitochondrial donation related licence

applications would likely be sought per annum.

It is also anticipated that if the clinical trial of

mitochondrial donation were to prove successful in minimising the risk of

future generations inheriting severe mitochondrial disease, this would provide

a potentially significant cost saving to the health and social welfare systems

through a reduced burden of disease and increased potential for workforce

participation. However, it not currently possible to provide estimates of these

potential savings before any outcomes of the trial have been realised.[151]

Attachment B to the Regulation Impact Statement (RIS) on

pages 86 to 94 of the Explanatory Memorandum to the Bill provides calculations

of the costs associated with the three policy proposals discussed by the RIS:

- maintain

the status quo (mitochondrial donation is not legalised in Australia)

- legalise

mitochondrial donation in Australia as a pathway to clinical use and

- support

access to overseas treatment options.[152]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011, the Government has assessed the Bill’s

compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or declared in the

international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The Government

considers that the Bill is compatible.[153]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights had no

comment in relation to the Bill.[154]

Key issues

and provisions

Overview

The use of mitochondrial donation techniques is currently

prohibited under the PHCR Act and the RIHE Act.[155]

Accordingly, the Bill amends these two Acts, and the RIHE Regulations to permit

the staged introduction of these techniques.

It is an offence under the current PHCR Act to:

- create

or develop embryos through the process of fertilisation with genetic material

from more than two people and

- make

heritable changes to the genome of a human embryo for reproductive purposes.[156]

In part, this ban does not extend to pronuclear transfer

(PNT), which is currently permitted under licence, as the technique uses two zygotes,

created with the genetic material of two people, however this technique is

prohibited from creating human embryos for reproductive purposes.[157]

This Bill proposes two significant changes which would allow, under licence, the creation of an embryo

for reproductive purposes with:

- the

genetic material of more than two people and

- changes

to its genome that would be heritable by the child’s

descendants.

Only two licences would allow for the use of these embryos

for reproductive purposes, the clinical trial licence and the clinical practice

licence. Stage 1 of mitochondrial donation will introduce the clinical trial

licence. The clinical practice licence has been identified for potential

introduction in Stage 2 of mitochondrial donation.[158]

In addition, under the RIHE Act, the woman and her

‘spouse’, if any, will be permitted to nominate only male embryos for

placement.[159]

As outlined in the background, sex selection through the use of ART is

permitted in Australia but is an option reserved for cases that would reduce

the risk of transmission of a genetic condition or disease that would severely

impact the person’s quality of life.[160]

Given the scientific and ethical considerations of sex selection for

mitochondrial donation, the Bill requires a woman/ the couple to attend

counselling before deciding if they would like to only place a male embryo.

Stage 1 of mitochondrial donation would be through a clinical

trials framework for both the licence holder and the ‘trial participant’ (that

is, the woman who is seeking to use mitochondrial donation for reproductive

purposes). Stage 2, if implemented, would consider the introduction of clinical

practice licences and any woman seeking to use mitochondrial donation for

reproductive purposes would be known as a ‘patient’ instead.

The criteria to become a trial participant (or patient)

includes evidence that the woman’s child would be at an increased risk of

developing severe mitochondrial disease. The Bill would not allow for the use

of mitochondrial donation techniques for any other reproductive purpose than to

minimise the risk of a child developing severe mitochondrial disease.[161]

Changing the

term ‘licence’ to ‘general licence’

The Bill’s introduction of the new term ‘mitochondrial

donation licence’ means that the current ‘licence’ used throughout both the RIHE

Act and the PHCR Act is no longer sufficient. ‘Licence’ is currently

defined to mean a licence issued under section 21 of the RIHE Act.[162]

In order to differentiate the ‘mitochondrial donation licences’ from the other

‘licences’ within the legislation, the Bill systematically amends the term ‘licence’

in both the RIHE Act and the PHCR Act to ‘general licence’.[163]

PHCR Act

amendments

Changes to

legalise the use of mitochondrial donation

The Bill makes significant changes to the PHCR Act by

amending sections of Part 2—Prohibited practices, allowing

for the use of mitochondrial donation techniques for reproductive purposes under

the relevant mitochondrial donation licences.

Creating human embryos for a

purpose other than achieving pregnancy

Currently, section 12 of the PHCR Act makes it an

offence to create a human embryo (by fertilising the egg with sperm outside the

body of a woman) for a purpose other than achieving pregnancy in a woman. Items

2 and 3 amend section 12 to allow the intentional creation of a

human embryo for purposes other than to achieve pregnancy in a woman, provided

the creation is authorised by the relevant mitochondrial donation licence.

This amendment has been made to allow a person to create

embryos for research and training purposes under the relevant mitochondrial

donation licences.

Creating human embryos with genetic

material from more than two people

Currently, section 13 of the PHCR Act makes it an

offence to intentionally create or develop a human embryo by the process of

fertilisation where the embryo contains genetic material provided by more than two

persons. Item 4 amends section 13 to allow the creation or development

of a human embryo that contains the genetic material of more than two persons provided

the creation is authorised by the relevant mitochondrial donation licence.

Due to the DNA contained within mitochondria, this amendment

has been made to allow the creation of embryos using DNA from three people, the

nDNA from the prospective parents and the mtDNA from the donor.

Heritable changes in the genome

Currently, section 15 of the PHCR Act makes it an

offence to make heritable changes to the genome of a human embryo. Item 5 amends

section 15 to allow heritable changes to be made to the genome of a

human embryo provided those changes are authorised under the relevant mitochondrial

donation licence.

The heritable change is in reference to the donor’s mtDNA.

Instead of inheriting the prospective mother’s mtDNA, a child born from

mitochondrial donation will inherit and, if female, has the ability to pass on

to the next generation, the donor’s mtDNA.

When prohibited embryo can be used

Currently, subsection 20(3), makes it an offence to

intentionally place an embryo in the body of a woman knowing that, or reckless

as to whether, the embryo is a prohibited embryo. The relevant prohibited

embryos for these amendments are defined in subsection 20(4) and include:

- a

human embryo created by a process other than the fertilisation of a human egg

by human sperm (paragraph (a))

- a

human embryo that contains genetic material provided by more than two persons

(paragraph (c))

- a

human embryo that contains a human cell whose genome has been altered in such a

way that the alteration is heritable by human descendants of the human whose

cell was altered (paragraph (f)).

Item 6 amends subsection 20(3) to allow for the

intentional placement of a prohibited embryo in the body of a woman, if the

embryo meets the definitions under paragraphs 20(4)(a), (c) and (f), and is

authorised under a mitochondrial donation licence.

Subsection 13.3(3) of the Criminal Code provides that

a defendant who wishes to rely on any exception, exemption, excuse,

qualification or justification provided the law creating an offence bears an

evidential burden in relation to that matter, which would require adducing or

pointing to evidence that suggests a reasonable possibility that the matter

exists. Item 7 will insert proposed subsection 20(5) into the PHCR

Act, to provide that, despite subsection 13.3(3) of the Criminal Code,

a defendant does not bear an evidential burden in relation to any matter in

subsection 20(3). This means that a person being prosecuted for an offence

under subsection 20(3) will not bear an evidential burden as to whether an