Robert Dolamore

This brief provides an overview of the economic and fiscal

context for the 2016–17 Budget.

The

economic context

The

domestic economic outlook

Over the past year Australia’s transition from mining driven

growth to broader-based growth has gained some traction. In its latest Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP), the

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reports that the non-mining sector expanded at

an above average rate in 2015, with growth strongest in services industries.[1] The impetus for a rebalancing towards non-mining sector activity has come

primarily from stronger dwelling investment and household consumption supported

by an accommodative monetary policy. The depreciation of the Australian dollar

since early 2013 has also helped by boosting demand for Australia’s exports

including non-mining export oriented industries such as tourism and higher

education. This transition has played out against a backdrop of falling

commodity prices, rapidly declining mining investment, expanding resources

exports and at times volatile global financial, equity and commodity markets.

However, revisions to Treasury’s forecasts suggest the

transition to broader-based growth has been slower than expected

(Table 1). At the time of last year’s Budget, Treasury and the RBA were

forecasting growth would strengthen to around its long-term average of 3.25 per

cent in 2016–17. Treasury is now expecting the economy will grow by

2.5 per cent in 2016‑17, unchanged from the previous year. The

RBA is slightly more optimistic, forecasting growth of 3 per cent in

2016‑17 (taking the mid-point of the RBA’s forecast range). Both Treasury

and the RBA are forecasting the economy will grow by around 3 per cent in 2017‑18.

Table 1: Treasury and the Reserve Bank of

Australia’s near-term growth forecasts (real GDP, per cent)

| |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

| Treasury |

| Budget 2015‑16 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

| Budget 2016‑17 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

3.0 |

| The Reserve Bank of

Australia |

| SMP* May 2015 |

2.0–3.0 |

2.5–4.0 |

… |

| SMP May 2016 |

2.5 |

2.5–3.5 |

2.5–3.5 |

*

Statement on Monetary Policy.

Source: Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2015–16, May 2015, Statement 1 Table 2, p. 1-7;

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2016–17, May 2016, Statement 1, Table 2, p. 1-8;

Reserve Bank of Australia, Statement on

Monetary Policy, May 2015,

Table 6.1, p. 65; Reserve Bank of Australia, Statement on

Monetary Policy, May 2016,

Table 6.1, p. 61.

Growth strengthened in the second half of 2015, with

particularly strong growth in the September quarter of 1.1 per cent. Growth

moderated in the December quarter to around 0.6 per cent and the RBA considers

this more moderate momentum has continued into 2016.[2]

The dynamics of growth are not expected to change markedly

in the near-term. Growth is expected to continue to be supported by stronger

household consumption, dwelling investment, resources exports and net services

exports. While declining mining investment will continue to weigh on growth for

some time yet, the RBA notes it is likely to have had its biggest impact on

growth in 2015‑16.[3]

Some

selected Australian economic indicators

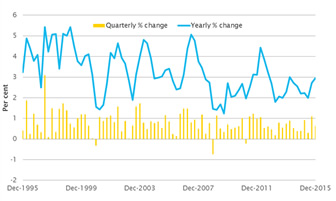

Real GDP growth (per cent)[4] |

- Real GDP increased by 0.6 per cent

in the December quarter. This was above market expectations.

- Annual growth was 3 per cent, slightly

higher than Treasury’s revised estimates of Australia’s potential growth rate

of 2.75 per cent.

- Consumer spending, dwelling investment and

public spending all contributed to growth.

- Declining business investment detracted from growth.

|

|

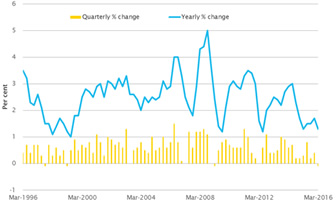

Inflation (CPI*, per cent)[5] |

- Headline inflation fell by

0.1 per cent in the March quarter, which was sharply lower than

market expectations.

- In annual terms headline inflation was

1.3 per cent, down from 1.7 per cent in the December quarter.

Although there were some temporary factors, the results suggest broad-based

weakness in domestic cost pressures.

- Underlying inflation was estimated to be

around 1.5 per cent in annual terms down from around

2 per cent in the December quarter.

*Excluding interest and tax changes of 1999-00. |

|

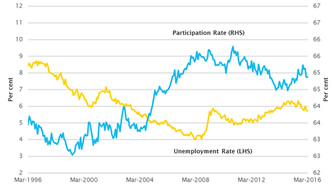

Unemployment rate & participation rate (per cent)[6] |

- The unemployment rate (seasonally adjusted)

decreased by 0.1 of a percentage point to 5.7 per cent in March.

- The participation rate (seasonally adjusted)

was steady at 64.9 per cent.

- Employment increased by 26,100 in March, which

was above market expectations.

- Employment grew by 2 per cent in the

year to March.

|

|

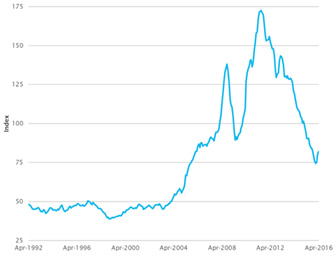

Australia’s terms of trade (index)[7] |

- In recent years large falls in commodity

prices have driven a significant decline in Australia’s terms of trade.

- In seasonally adjusted terms the terms of

trade declined by 3.2 per cent in the December quarter and by

12 per cent annually.

- Australia’s terms of trade have fallen by

around 34 per cent since their peak in late 2011.

|

|

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) Index of Commodity Prices

(SDR, 2014‑15 average =100)[8] |

- The RBA reports that preliminary estimates for

April indicate the index rose by 2 per cent (on a monthly average

basis) in Special Drawing Right (SDR) terms, after increasing by 6.3 per cent

in March.[9]

- Over the past year, the index has fallen by

9.4 per cent in SDR terms, led by declines in the prices of base

metals.

- The index has fallen by around

52 per cent in SDR terms since its peak in July 2011.

|

|

Labour Costs, Year-ended change (per cent)[10] |

- Labour cost pressures have been weak in recent

times.

- The wage price index (WPI) is calculated by

comparing the cost of wages over time for the same work level and output.

- The WPI increased by 0.5 per cent (seasonally

adjusted) in the December quarter.

- The annual change in the WPI was 2.2 per cent,

the lowest rate of wages growth since the start of the series in 1998.

|

|

A pick-up in non-mining business investment remains

important to boosting productivity, growth and future living standards.

However, as the Government notes in Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2016‑17, this has been

slower than expected.[11]

It appears unlikely there will be a strong lift in

non-mining business investment in the near term. Budget Paper No. 1 cites the Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS) Private New Capital Expenditure and Expected Expenditure Survey (CAPEX)

and Treasury’s own business liaison programme as indicating that businesses are

continuing to wait before committing to new investment.[12] The RBA also considers that the outlook for non-mining

business investment is subdued but observes:

However, very low interest rates and the depreciation of the

Australian dollar over the past few years have supported an improvement in

business conditions (which is clearly evident in the various survey measures

and consistent with the rise in employment) and there is evidence that

investment has increased in areas of the economy that have been less affected

by the decline in mining investment and commodity prices.[13]

The March quarter inflation figures were sharply lower than expected. The headline consumer price index

(CPI) fell by 0.1 per cent (in seasonally adjusted terms) to be

1.3 per cent higher over the year. The RBA reports that although

there were some temporary factors (for example, lower fuel prices) the data

suggest there has been broad-based weakness in domestic cost pressures.[14] A negative quarterly CPI reading is relatively rare. In the last 20 years

there have been only three other occasions when the quarterly CPI reading was

negative. Underlying inflation decreased to be around 0.25 per cent

in the March quarter and about 1.5 per cent over the year.[15] The softness of the latest inflation figures prompted the RBA Board to cut the

cash rate by 25 basis points to a new historic low of

1.75 per cent on 3 May 2016.[16]

Many central banks in recent years have been grappling with

low inflation.[17] Indeed,

the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reports in its latest World Economic Outlook that in the

advanced economies underlying inflation remains well below central bank targets

and deflationary pressures are a risk. [18] Against this international backdrop, European Central Bank President, Mario

Draghi, outlined in a speech earlier this year why it is important for central

banks to act within their mandates to ensure transitory deflationary pressures

do not lead to permanently lower inflation.[19]

In its latest SMP the RBA revised down its inflation

forecasts. [20] Headline

inflation is expected to converge towards underlying inflation over the

forecast period. Both measures are forecast to be still below

2 per cent (taking the midpoint of the RBA’s forecast band) by

December 2016 and at the bottom of the RBA’s inflation target band of 2 to 3

per cent out to June 2018 (again taking the midpoint of the RBA’s forecast

band). The downward revisions to the RBA’s inflation forecasts reflect a view

that domestic cost pressures, including wages growth, will pick-up more gradually

than previously thought.

Labour market

conditions have been noticeably stronger than previously forecast adding

weight to the view that Australia’s transition to broader-based growth has

gained some traction. In last year’s Budget Treasury forecast that employment

would grow by 1.5 per cent in 2015‑16 and the unemployment rate

would be 6.5 per cent in the June quarter.[21] The latest Budget forecasts show stronger employment growth of 2 per cent

in 2015–16 and a lower unemployment rate of 5.75 per cent.[22]

Over the past year employment growth has been supported by

moderate wage growth and the transition to more labour-intensive sectors of the

economy such as household and business services.

Both Treasury and the RBA are expecting labour market

conditions will continue to improve in 2016‑17, although at a slower pace

than in 2015‑16. Treasury is forecasting employment will grow by

1.75 per cent in 2016‑17 and the unemployment rate will fall

slightly to 5.5 per cent in the June quarter. This is broadly consistent

with the RBA’s view.

Just as rising commodity prices and the upswing in mining

investment affected some jurisdictions more than others, the downswing of the mining boom has

been felt unevenly across Australia. During the upswing the resource rich jurisdictions

of Western Australia (WA), Queensland and the Northern Territory (NT) benefited

from the direct and indirect effects of surging mining investment and

employment. While other jurisdictions also benefited many trade exposed

non-mining industries in the south east of Australia found conditions difficult

as the boom drove the Australian dollar higher. More recently economic activity

outside the resource-rich jurisdictions has picked up helped in part by stronger

demand for household and business services. In contrast WA has faced a

challenging transition as mining investment and employment unwinds.

One window on the regional effects of Australia’s current

transition is provided by CommSec’s quarterly State of the States report.[23] CommSec assesses the economic performance of

Australia’s states and territories using eight indicators: economic growth;

retail spending; equipment investment; unemployment; construction work done;

population growth; housing finance and dwelling investment. In its latest report CommSec found New South Wales (NSW), Victoria and the

Australian Capital Territory (ACT) held the first three spots in terms of

overall economic performance. Three years ago WA and the NT held the first two

spots respectively.[24] WA now ranks 6th in terms of overall economic performance and the NT ranks 4th.

Risks

On the domestic front there are a number of risks to the

economic outlook. On the upside it is possible that if wages growth strengthens

by more than currently forecast this would likely feed through to stronger

household consumption, which would boost domestic demand.

A key downside risk is around the timing of the pick-up in

non-mining sector business investment. One plausible scenario is that the

support to growth coming from stronger dwelling investment and a lower

Australian dollar wanes over coming months and consequently pushes the pick-up

in non-mining sector business investment further out.

There is a risk that a sharp downturn in the Australian

housing market would expose households and the banking sector to increased

stress. Tightening credit conditions would weigh on domestic demand as would the

negative confidence and wealth effects a downturn of this nature would have.

Finally, it is possible that like recent international experience,

deflationary pressures in Australia prove more stubborn than currently thought.

Some economists have raised the possibility that deflationary pressures in the

advanced economies reflect structural factors (for example related to

demographics, the long-term cycle in commodity prices, technological change and

the effects of globalisation).[25] To the extent this is the case there is a risk these pressures may persist and

become embedded in people’s expectations and decision-making. If deflationary

pressures prove to be less transitory than currently thought it would further

complicate an already challenging macroeconomic policy environment.

The global

economic outlook

The global outlook matters because as a relatively small

open economy Australia is affected by developments overseas through financial,

trade and investment linkages and confidence and wealth channels. Since the

beginning of the year the economic outlook for the global economy has become

more subdued. The New Year saw one of the worst stock market sell-offs since

the 2008 global financial crisis (GFC).[26] Initially, global markets focussed on slowing growth in China and rising

vulnerabilities in emerging market economies more generally. This was followed

by heightened concerns about bank profitability in an environment in which the

outlook for the global economy looked more subdued and there were increased

expectations of further reductions in interest rates in some of the major

economies.

Since then global markets have calmed but there remain concerns

about the extent to which market sentiment remains relatively unanchored,

lacking a clear sense of what the new long-term sustainable growth path is.[27]

While forecasters have trimmed their near-term global growth

forecasts, growth is still expected to strengthen gradually over the next

couple of years (Table 2). The IMF considers this improvement is

contingent on growth picking up in emerging market and developing economies as

the outlook for advanced economies remains relatively subdued.[28]

Treasury’s growth forecasts for the global economy are

broadly in line with those of the IMF (Table 2). However, Treasury is a

little less optimistic about the near-term growth prospects of the United

States (US). Forecasts from Oxford Economics, a private global advisory firm,

are provided in Table 2 as a point of comparison. The summary below draws

on all three sources.

- United

States: growth has slowed in recent quarters but is expected to firm in the

second half of 2016. Subdued global growth and a strong US dollar have weighed

on net exports and manufacturing investment while lower oil prices have

triggered a contraction in investment in the energy sector. Against this growth

is being supported by solid labour market gains, moderate growth in consumer

spending, accelerating housing activity and strengthening balance sheets.

- China:

growth is expected to slow in 2016 in line with official growth targets. The

Chinese authorities have provided some additional stimulus which is expected to

support growth in the near-term. This stimulus has included boosting credit

growth, easing housing policies and increasing infrastructure investment.

Growth is also being supported by robust consumer spending and an expanding

services sector. However, recent stimulus measures are unlikely to be

sustainable in the longer-term and China continues to face significant

challenges including a sizeable debt burden and the need to transition to more

balanced and sustainable growth.

- Japan:

the recovery in the Japanese economy stalled mid-way through 2015 in the face

of weaker demand from China and other Asian economies and sluggish private

consumption. The near-term outlook for the Japanese economy remains relatively

subdued with the recent strength of the Japanese yen weighing on exports and any

improvement in domestic demand looking relatively muted at this stage.

- India:

growth continues to be robust and Treasury and the IMF are forecasting it will

continue to strengthen over the next couple of years. Most of the impetus for

growth recently has come from household consumption and public investment. This

is expected to broaden as private investment and net exports make a stronger

contribution to growth helped by recent reforms. Oxford Economics is a little

less optimistic forecasting growth will soften slightly over the forecast

period.

- Euro Area:

the modest recovery in the Euro Area is expected to continue with weaker

external demand offset by the positive effects of accommodative monetary policy,

lower energy prices, a modest fiscal expansion and supportive financial

conditions.

Table 2: Treasury, IMF

and Oxford Economics international growth forecasts (per cent)

| |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

| United States |

|

|

|

|

| Treasury |

2.4 |

2.0 |

2.25 |

2.25 |

| IMF |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

| Oxford Economics |

2.4 |

2.0 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

| Euro area |

|

|

|

|

| Treasury |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

| IMF |

1.6 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

| Oxford Economics |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

| China |

|

|

|

|

| Treasury |

6.9 |

6.5 |

6.25 |

6.0 |

| IMF |

6.9 |

6.5 |

6.2 |

6.0 |

| Oxford Economics |

6.9 |

6.5 |

6.2 |

5.9 |

| Japan |

|

|

|

|

| Treasury |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.25 |

0.5 |

| IMF |

0.5 |

0.5 |

-0.1 |

0.4 |

| Oxford Economics |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

| India |

|

|

|

|

| Treasury |

7.3 |

7.5 |

7.5 |

7.75 |

| IMF |

7.3 |

7.5 |

7.5 |

7.6 |

| Oxford Economics |

7.3 |

7.4 |

7.2 |

7.0 |

| World |

|

|

|

|

| Treasury |

3.1 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

3.75 |

| IMF |

3.1 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

| Oxford Economics |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

Source:

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2016–17, 2016, Statement 2, Table 2, p. 2-9;

International Monetary Fund, World economic

outlook: too slow for too long,

April 2016; Table 1.1, p. 2.; Oxford Economics, World Economic Prospects, April 2016.

In recent years Australia has benefited from growth in its

major trading partners being higher than the world as a whole.[29] As the RBA notes this has in part reflected the increasing share of Australia’s

exports going to China.[30] The RBA is forecasting trading partner growth a bit below 4 per cent

over the next couple of years.[31]Treasury

is forecasting that growth in Australia’s major trading partners will remain

around 4 per cent in the forecast period.[32]

Risks

The global economy also poses a number of risks for the

Australian economy. On the upside it is possible a lower exchange rate than

currently forecast could provide additional support to Australia’s transition

to broader based growth by boosting demand in Australia’s trade exposed

non-mining sectors.

Even though concerns about the Chinese economy appear to

have eased recently, the potential for a sharp downturn in China remains the

main perceived near-term risk to the global economy. If this was to eventuate

it would trigger renewed volatility in global markets and quickly flow through

to China’s major trading partners. Australia would be hit by weaker demand for

its commodity and other exports, weaker Chinese investment and the negative

confidence and wealth effects these developments would cause. Australia would

also be hit by the flow-on effects of a downturn in the Chinese economy for the

Asian region and the global economy more generally.

There is a risk of persistently slow growth among the

advanced economies and that growth is not only slow but these economies

struggle to fully use their productive potential. It is possible that

structural factors are at work; for example, those related to demographics,

debt levels, technological change and inequality, which could result in a

sustained weakening of demand relative to supply in these economies.

If Britain votes to exit the European Union in June 2016 it

is likely there would be considerable uncertainty about the implications for

Britain and Europe. There is a risk that this could trigger further volatility

in global markets with negative flow-on effects for the rest of the world.

Finally, geopolitical tensions (for example in the Middle

East and the South China Sea) have the potential to disrupt global financial,

investment and trade flows and dampen confidence.

Australia’s

longer-term economic outlook

The longer-term challenges and opportunities that Australia

faces are also an important backdrop to the budget. These longer-term

influences encompass the economic, social and environmental dimensions of

community wellbeing. Generally, they change little from year to year but

nonetheless over time have the potential to have a large cumulative impact on

Australia’s economic prosperity and future living standards.

The list of challenges and opportunities that are likely to

shape Australia’s longer-term outlook include:

- an ageing population

- the economic rise of Asia

- climate change

- natural resource depletion

- changing patterns of global demand and

- new knowledge and

technologies.

Of a different nature, but also important, is the risk of

external shocks to the Australian economy. They are hard to predict but

nevertheless occur not infrequently.

The budget provides an important mechanism through which

governments can try to manage the effects of longer-term influences. For

example, through long-term investment, governments can build the capabilities

needed to make the most of expected future opportunities and the flexibility

and resilience needed in the face of less favourable long‑term trends.

In the 2016–17 Budget the

Government set out its economic plan, which, it says, seeks to facilitate

Australia’s transition to a stronger and more diversified economy.[33] The key elements of this plan are a focus on jobs and economic growth; the tax

system; and seeking to balance the budget and reduce the burden of long-term

debt.

The

implications of the economic outlook for the Budget

Treasury’s assessment of the economic outlook is reflected

in the key economic parameters used to estimate revenue and expenditure items.

Treasury provides forecasts of the key macroeconomic parameters for the budget

year and the following financial year and projections of these parameters for

the following two financial years.

Table 3 shows how Treasury’s forecasts of major

economic parameters have tracked over the past year. Overall the revisions to

the 2016‑17 forecasts suggest a softer reading of Australia’s economic

conditions. Real GDP growth, the CPI, the wage price index and nominal GDP

growth have all been revised down. Against this, the unemployment rate has been

revised down reflecting stronger labour market conditions and the terms of

trade are now forecast to increase slightly.

The fiscal estimates and projections are sensitive to

changes in the key economic parameters. Even relatively small changes in the

parameters can affect the budget bottom line.

For example, in Statement 2 of Budget Paper No. 1, the Government highlights the

uncertainty around movements in commodity prices.[34] Forecasts of commodity prices have an important bearing on the outlook for

nominal GDP growth and hence government revenue. The Budget assumes the price

of iron ore will be US$55 per tonne Free on Board (FOB), compared with US$S39

per tonne FOB in MYEFO 2015–16. The results of a sensitivity analysis presented

in the Budget reveal that a US$10 per tonne reduction/increase in the iron ore

price results in just over a $6 billion reduction/increase in nominal GDP

in 2016‑17.[35]

Statement 7 of Budget Paper No. 1 provides a detailed

analysis of the historical performance of budget forecasts and estimates of

uncertainty around the forecasts.[36] It also provides a sensitivity analysis of the Budget estimates to changes in

key assumptions as required under the Charter

of Budget Honest Act 1998. For example, the sensitivity analysis includes

an assessment over the forecast period of the impact on GDP, labour market

conditions and prices of a permanent 10 per cent fall in world prices

for non-rural commodity exports through 2016‑17 (which is consistent with

a fall in the terms of trade of 4.75 per cent and a reduction in

nominal GDP growth of 1 per cent by 2017‑18).[37] The analysis shows the overall impact of the fall in the terms of trade is a

decrease in the underlying cash balance of around $2.2 billion in 2016‑17

and around $5.4 billion in 2017‑18.[38]

The Fiscal

context

The

Government’s fiscal strategy and broader policy agenda

The fiscal

strategy

Consistent with the requirements of the Charter of Budget Honest Act 1998, the Government has set out in

the Budget its medium-term fiscal strategy. The Government’s objective is to

‘achieve budget surpluses, on average, over the course of the economic cycle’.[39] The details of the fiscal strategy can be found in Statement 3 of Budget Paper No. 1 (see box 1

on page 3-7).

Table 3: Treasury

forecasts of major economic parameters (per cent)

| |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

| Real

GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

2.5 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

2.2* |

2.5 |

2.75 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

2.2* |

2.5 |

2.5 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

| Employment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

1.5* |

2.0 |

1.75 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

1.6* |

2.0 |

1.75 |

1.75 |

1.25 |

1.5 |

| Unemployment Rate |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

6.25 |

6.5 |

6.25 |

6.0 |

5.75 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

6.0* |

6.0 |

6.0 |

5.75 |

5.5 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

6.1* |

5.75 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

5.5 |

| Consumer price index |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

1.75 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

1.5* |

2.0 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

1.5* |

1.25 |

2.0 |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

| Wage price index |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

2.5 |

2.5 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

2.3* |

2.5 |

2.75 |

2.75 |

3.0 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

2.3* |

2.25 |

2.5 |

2.75 |

3.25 |

3.5 |

| Nominal GDP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

1.5 |

3.25 |

5.5 |

5.25 |

5.5 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

1.6* |

2.75 |

4.5 |

5.0 |

5.25 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

1.6* |

2.5 |

4.25 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

| Terms of trade |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Budget 2015–16 |

-12.25 |

-8.5 |

0.75 |

|

|

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 |

-10.2* |

-10.5 |

-2.25 |

|

|

|

| Budget 2016–17 |

-10.3* |

-8.75 |

1.25 |

0.0 |

|

|

* outcomes

Source:

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2015–16, 2015, Statement 1, Table 2, p. 1-7,

Statement 2, Table 1, p. 2-5; S Morrison (Treasurer) and M

Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2015–16,

2015, Table 1.2, p. 3, Table 2.2, p. 9; Australian

Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 1, Table 2, p. 1-8,

Statement 2, Table 1, p. 2-6.

Since the 2014–15Budget, the Government has also set itself

a budget repair strategy, which is consistent with and complements the

medium-term fiscal strategy. When originally introduced the objective of the

budget repair strategy was ‘to deliver budget surpluses building to at least

1 per cent of GDP by 2023‑24’.[40] In the 2015‑16 MYEFO the Government moved away from specifying a target

date, with the goal becoming ‘to deliver budget surpluses building to at least

1 per cent of GDP as soon as possible’.[41] This remains the objective of the Government’s budget repair strategy as set

out in Budget Paper No. 1 (see

box 1 on page 3-7).

In the 2015–16 Budget the Government was projecting the

underlying cash balance would improve over the period to 2018‑19,

reaching a small surplus by 2019‑20.[42] The Government’s latest medium-term projections show that the underlying cash

balance is not expected to reach a surplus of around 0.2 per cent GDP

until 2020‑21.[43] After that the surplus is projected to peak at around 0.3 per cent of

GDP in 2021‑22 before declining gradually over the period to 2026‑27.[44] Given the difficulty of forecasting beyond the forward estimates period there

is considerable uncertainty about whether even these relatively modest

surpluses will be achieved.

The Government acknowledges the medium-term outlook for the

underlying cash balance does not meet key elements of its fiscal strategy and

much more needs to be done.[45]

How much additional fiscal adjustment is needed in future

budgets will, in part, depend on how strongly the economy grows over the

medium-term. If economic growth turns out to be stronger than currently

projected, the size of the fiscal adjustment task will be smaller than would

otherwise be the case.

A key element of the Government’s budget repair strategy is

a commitment to offsetting all new policy decisions. In Budget

Paper No. 1 the Government notes that all new spending measures in

the Budget have been offset by savings in payments and not by policy decisions

to increase tax revenue.[46]

The Government has also indicated that it remains committed

to implementing Budget measures which have been delayed in the Senate.[47] The Government estimates that the impact of the delays will be to worsen the

budget bottom line by $2.2 billion over the five years to 2019‑2020.[48]

The

Government’s broader policy agenda

In Budget Paper

No. 1 the Government highlights the ways it is redirecting government

spending to investments which it considers will boost productivity and

workforce participation. In this regard, key initiatives include:

- The ten

year enterprise tax plan—aims to support growth, higher wages and jobs by

lowering the corporate tax rate over time to an internationally competitive

level and provides for early cuts for smaller businesses. The Government claims

this initiative will deliver a permanent increase to GDP of just over

one per cent in the long term.

- Changes to

superannuation—aims to improve the sustainability, flexibility and

integrity of the superannuation system. The Government has announced it is

introducing or lowering transfer balance and contribution caps and providing

savings support to those who need it most. The Government has also announced changes

to allow people to make catch-up contributions; allow all individuals under the

age of 75 years to claim a tax deduction for personal contributions; and

extend the eligibility for individuals to claim a tax offset for contributions

made to their spouse’s superannuation.

- Youth

Employment Package—aims to help young people become more competitive in the

labour market by enhancing their skills, providing opportunities for work

experience and supporting their transition from welfare to work.

- Infrastructure

spending—the Government is investing $50 billion in infrastructure

from 2013‑14 to 2019‑20. It reports in the Budget that around 100

major projects are currently under construction and 80 are in the

pre-construction phase.

- Defence

investments—the Government has provided an additional $29.9 billion

over the period to 2025‑26 for defence investments in order to strengthen

Australia’s defence capabilities and support Australia’s advanced local defence

manufacturing industry.

- Financial

assistance to hospitals and schools—with the Government linking three-year

funding arrangements in these areas to reforms which focus on improving quality

and patient safety in hospitals and improving student outcomes in schools.

As part of this year’s Budget Review, the Parliamentary

Library’s research specialists have prepared briefs on the major policy decisions

taken in the Budget.

The fiscal

position

As this year’s Budget is the final budget delivered to the

44th Parliament it is appropriate to look back at how the budgetary position

has evolved since the Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook (PEFO) was released

in August 2013. The brief then considers in more detail the fiscal position and

outlook set out in the Budget.

A look

back – PEFO to Budget 2015–16

The Charter of Budget

Honesty Act 1998 requires the Secretary to the Treasury and the Secretary

of the Department of Finance to publicly release a PEFO report within 10 days

of the issue of the writ for a general election. Accordingly, PEFO was released

after the writ was issued for the 2013 election. It provided updated

information about Australia’s economic and fiscal outlook, including fiscal

projections out to 2016‑17.

This section briefly outlines how estimates of two headline

fiscal measures, namely the underlying cash balance and general government

sector net debt, have changed since PEFO.

The underlying

cash balance

At the time of PEFO, Australia’s underlying cash balance was

estimated to turn around from a deficit of $30.1 billion in 2013‑14

to a small surplus of $4.2 billion by 2016‑17. Over the four years

to 2016‑17 the accumulated deficits were projected to total $54.6 billion.

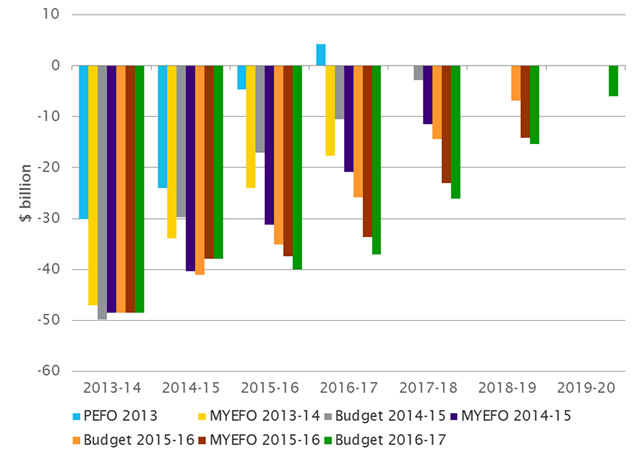

Since PEFO there has been significant fiscal slippage (Figure 1).

The size of budget deficits over this period has been progressively revised up.

The latest figures show the deficit in 2013‑14 was $48.5 billion

some $18.3 billion higher than estimated in PEFO. In 2016‑17 the

deficit is now estimated to be $37.1 billion some $41.3 billion

higher than at the time of PEFO. The latest numbers also reveal that over the

four years to 2016‑17 accumulated deficits total $163.4 billion some

$108.8 billion more than projected at the time of PEFO.

Revisions to the budget bottom-line reflect the impact of

policy decisions and/or parameter and other variations. Table 4 uses

information provided in successive budget and MYEFO documents to piece together

as much of a reconciliation of progressive revisions to the underlying cash

balance as possible. For 2013‑14 and 2014‑15 it is only possible to

provide a partial reconciliation.

Table 4 shows that over the four years to 2016‑17,

parameter and other variations account for the bulk of the fiscal slippage over

this period. A large part of this slippage is likely to be explained by lower

than expected commodity prices which have consistently resulted in significant

write-downs in government revenue.

The revisions to 2013‑14 stand out as being different

to that of the other three years of this period (Table 4). To the extent

that it is possible to attribute slippage between the effects of policy

decisions and parameter and other variations for 2013‑14, the figures

suggest policy decisions accounted for over half the fiscal slippage. In the

other three years policy decisions typically account for a much smaller share

of the total fiscal slippage.

Figure 1:

Revisions to the underlying cash balance ($m)

Source: The Secretary to the

Treasury and The Secretary to the Department of Finance and Deregulation, Pre-Election

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2013,

The Commonwealth of Australia, August 2013, Table 1, p. 1; J Hockey

(Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2013-14,

December 2013, Appendix D, Table D1, p. 265; Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2014-15, May 2014, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10‑7; J

Hockey (Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid‑year

economic and fiscal outlook 2014‑15, December 2014, Appendix D, Table D1, p. 267; Australian

Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2015–16, May 2015, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10-7; S

Morrison (Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2015–16,

December 2015, Appendix D, Table D.1, p. 291; Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, May 2016, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10-6.

Looking further out, estimates of the size of the underlying

cash balance deficit for 2017‑18 and 2018‑19 have also been

progressively revised up (figure 1 and table 4). For both years

parameter and other variations account for over 90 per cent of the

slippage. The revisions since Budget 2015‑16 are discussed in more detail

below.

General

government sector net debt

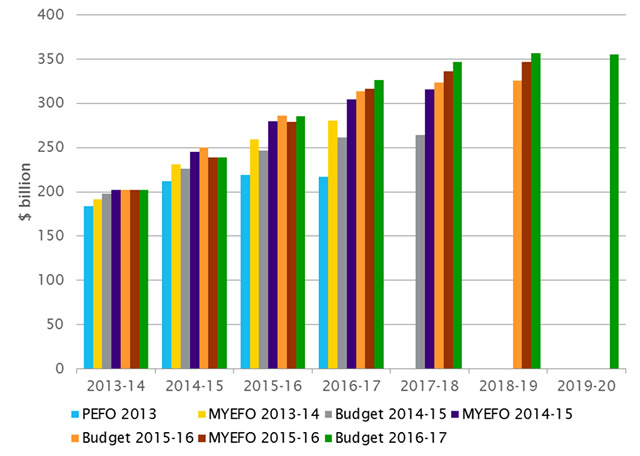

At the time of PEFO, general government sector net debt was

projected to increase from $184 billion in 2013‑14 to a peak of

$219 billion in 2015‑16 before decreasing slightly to

$217.3 billion in 2016‑17.

The latest figures reveal Australia’s net debt position has

deteriorated markedly from what was projected at the time of PEFO (Figure 2).

Net debt reached $202.5 billion in 2013‑14, some $18.5 billion

more than estimated in PEFO. It is estimated to increase to $326 billion

in 2016‑17, some $108.7 billion more than projected in PEFO.

The latest budget figures show net debt peaking at $356.4 billion

(18.8 per cent of GDP) in 2018‑19 before decreasing slightly to

$355.1 billion (17.8 per cent of GDP) in 2019‑20. Changes in

the Commonwealth’s balance sheet since Budget 2015‑16 are discussed in

more detail below.

Table 4: Revisions to

the Underlying Cash Balance (UCB): Pre-Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook

(PEF0) 2013 to Budget 2016–17

| |

2013-14 |

2014-15 |

2015-16 |

2016-17 |

2017-18 |

2018-19 |

2019-20 |

| PEFO 2013 UCB |

-30,142 |

-23,981 |

-4,662 |

4,199 |

|

|

|

| Policy changes |

-10,266 |

-655 |

-1,505 |

-1,274 |

|

|

|

| Parameter & other variations |

-6,582 |

-9,272 |

-17,916 |

-20,592 |

|

|

|

| MYEFO 2013-14 UCB |

-46,989 |

-33,907 |

-24,083 |

-17,668 |

|

|

|

| Policy changes |

-514 |

1,718 |

5,934 |

10,414 |

|

|

|

| Parameter variations |

-2,352 |

2,416 |

1,065 |

-3,309 |

|

|

|

| Budget 2014-15 UCB |

-49,855 |

-29,773 |

-17,084 |

-10,562 |

-2,825 |

|

|

| Policy changes |

|

-2,314 |

-2,195 |

-501 |

950 |

|

|

| Parameter & other variations |

|

-8,275 |

-11,960 |

-9,781 |

-9,606 |

|

|

| MYEFO 2014-15 UCB |

|

-40,362 |

-31,239 |

-20,844 |

-11,480 |

|

|

| Policy changes |

|

-578 |

-4,525 |

-2,547 |

-1,665 |

|

|

| Parameter & other variations |

|

-181 |

650 |

-2,445 |

-1,251 |

|

|

| Budget 2015-16 UCB |

|

-41,121 |

-35,115 |

-25,836 |

-14,396 |

-6,905 |

1,300 |

| Policy changes |

|

|

-2,516 |

-2,427 |

302 |

921 |

na |

| Parameter & other variations |

|

|

231 |

-5,404 |

-8,927 |

-8,246 |

na |

| MYEFO 2015-16 UCB |

|

|

-37,399 |

-33,667 |

-23,021 |

-14,229 |

-7,300 |

| Policy changes |

|

|

-195 |

-3,070 |

384 |

-1,494 |

5,894 |

| Parameter & other variations |

|

|

-2,352 |

-343 |

-3,484 |

319 |

-4,549 |

| Budget 2016-17 UCB |

-48,456 |

-37,867 |

-39,946 |

-37,081 |

-26,123 |

-15,406 |

-5,955 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Revisions: PEFO 2013 to

Budget 2016-17 (as far as possible) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Policy changes |

-10,780 |

-1,829 |

-5,002 |

595 |

|

|

|

| Percentage

of total revisions |

54.7 |

10.7 |

14.2 |

-1.4 |

|

|

|

| Parameter & other variations |

-8,934 |

-15,312 |

-30,282 |

-41,874 |

|

|

|

| Percentage

of total revisions |

45.3 |

89.3 |

85.8 |

101.4 |

|

|

|

| Total revisions |

-19,714 |

-17,141 |

-35,284 |

-41,279 |

|

|

|

Source: The Secretary to the

Treasury and The Secretary to the Department of Finance and Deregulation, Pre-Election

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2013,

The Commonwealth of Australia, August 2013, Table 7, p. 16; J Hockey

(Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2013–14,

December 2013, Table D5, p. 269; Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2014–15, May 2014, Statement 10, Table 5, p. 10-11; J

Hockey (Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid‑year

economic and fiscal outlook 2014‑15, December 2014, Appendix D, Table D6, p. 273; Australian

Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2015–16, May 2015, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10-7; Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2015–16,

December 2015, Appendix D, Table D.4, p. 297; Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, May 2016, Statement 10, Table 4, p. 10-12.

Figure 2:

Revisions to general government sector net debt ($m)

Source: The Secretary to the

Treasury and The Secretary to the Department of Finance and Deregulation, Pre-Election

Economic and Fiscal Outlook 2013,

The Commonwealth of Australia, August 2013, Table 7, p. 16; J Hockey

(Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2013–14,

Table D5, p. 269; Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2014–15, 2014, Statement 10, Table 5, p. 10-11; J Hockey

(Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for Finance), Mid‑year

economic and fiscal outlook 2014‑15, Appendix D, Table D6, p. 273; Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2015–16, 2015, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10-7; Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2015–16,

2015, Appendix D, Table D.4, p. 297; Budget strategy

and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 10, Table 4, p. 10-12.

Budget 2016‑17:

The fiscal position and outlook

The

underlying cash balance

The Budget forecasts an underlying cash deficit of

$37.1 billion (2.2 per cent of GDP) in 2016‑17, improving

to a projected deficit of $6.0 billion (0.3 per cent of GDP) in

2019‑20 (Table 5).

Table 5: The general

government sector: The underlying cash balance

| |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Underlying cash

balance

($m) |

-37,867 |

-39,946 |

-37,081 |

-26,123 |

-15,406 |

-5,955 |

| Per cent of GDP |

-2.4 |

-2.4 |

-2.2 |

-1.4 |

-0.8 |

-0.3 |

Source:

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10-6.

The size of the projected fiscal consolidation between 2016‑17

and 2019‑20 is around 1.9 per cent of GDP. By way of comparison

the size of the fiscal consolidation achieved between 2013‑14 and 2016‑17

is estimated to have been 0.9 per cent of GDP.

The pace of fiscal consolidation decreases slightly over the

forward estimates period being around 0.8 per cent of GDP between

2016‑17 and 2017‑18; 0.6 per cent of GDP between 2017‑18

and 2018‑19; and 0.5 per cent of GDP between 2018‑19 and

2019‑20.

General

government sector receipts

The revenue side accounts for most of the projected fiscal

consolidation between 2016‑17 and 2019‑20, with general government

sector receipts projected to increase by around 1.2 per cent of GDP

over the period (Table 6). Taxation receipts are projected to increase by 1.3 per cent

of GDP and non-taxation receipts to decrease slightly by 0.1 per cent

of GDP.

Table 6: General

government sector: Taxation receipts, non-taxation receipts and total receipts

| |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Taxation receipts

($m) |

353,494 |

364,507 |

382,769 |

410,165 |

438,821 |

468,278 |

| Per cent of GDP |

22.0 |

22.1 |

22.2 |

22.7 |

23.1 |

23.5 |

Non-taxation

receipts

($m) |

24,807 |

23,520 |

28,515 |

27,221 |

31,100 |

32,464 |

| Per cent of GDP |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

1.6 |

Total receipts

($m) |

378,301 |

388,027 |

411,284 |

437,385 |

469,921 |

500,742 |

| Per cent of GDP |

23.5 |

23.5 |

23.9 |

24.2 |

24.8 |

25.1 |

Source:

Australian Government, Budget strategy

and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 10, Table 3, p. 10-10.

Given that the Budget relies heavily on stronger taxation

receipts over the next four years to substantially reduce the underlying cash

deficit, much would appear to hinge on the Budget’s revenue forecasts. These

forecasts are sensitive to the underlying assumptions made about nominal

economic growth and wages growth:

- Nominal GDP growth provides a rough indication

of growth in the size of the tax base. Treasury is forecasting nominal GDP

growth of 4.25 per cent in 2016‑17 and 5 per cent a year for

the remainder of the forward estimates period. Nominal GDP growth in turn is

sensitive to changes in the terms of trade. Treasury is forecasting the terms

of trade to rise slightly by 1.25 per cent in 2016‑17 after

declining by 8.75 per cent in 2015‑16. The RBA’s latest

forecasts of the terms of trade suggest Treasury’s forecasts are plausible

given recent improvements in commodity prices.[49]

- The assumptions made about wages growth are important

for forecasting income tax revenue. Treasury is forecasting wages growth of

2.5 per cent in 2016‑17, 2.75 per cent in 2017‑18,

3.25 per cent in 2018‑19 and 3.5 per cent in 2019‑20.

The relatively modest pick-up in wages growth over the next two years is

plausible given that there is still a degree of spare capacity in the labour

market. It is also possible that wages growth may increase thereafter if labour

market conditions tighten as growth picks up.

While these assumptions are plausible, at this stage the

balance of risk is on the downside.

General

government sector payments

General government sector payments are projected to fall by

0.6 per cent of GDP between 2016‑17 and 2019‑20

(Table 7)

Real expenditure growth between 2016‑17 and 2019‑20

is forecast to average 2 per cent a year. This compares with average

real growth between 2013‑14 and 2016‑17 of 3 per cent a

year. This suggests that the Government will need to maintain considerable

fiscal discipline if it is to reduce expenditure as a share of GDP over the

forward estimates period.

Table 7: General

government sector: Payments

| |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

Payments

($m) |

412,079 |

424,961 |

445,045 |

459,934 |

481,484 |

502,556 |

| Per cent of GDP |

25.6 |

25.8 |

25.8 |

25.5 |

25.4 |

25.2 |

Source:

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 10, Table 1, p. 10-6.

The

structural budget balance

In Statement 3 of Budget Paper No. 1, the

Government reports on the structural budget balance.[50] Estimates of the structural budget balance remove the temporary changes to

revenues and expenditures—due to fluctuations in commodity prices for example—and

the extent to which economic output deviates from its potential level due to

the economic cycle. As the Government notes, when considered in conjunction

with other measures, estimates of the structural budget balance can provide

insights into the sustainability of current fiscal settings.

Estimates of the structural budget balance over the next

decade are marginally lower than at the time of the 2015‑16 MYEFO . This reflects that Treasury has revised down

its terms of trade outlook over the medium-term, which flows through downward

revisions to structural revenues.

The Budget is projecting that the overall level of the

structural budget balance will improve from a deficit of around

2 per cent of GDP in 2015‑16, to a series of small surpluses

from 2020‑21 onwards, converging to the underlying cash balance.[51]

How has

the short-term fiscal outlook changed?

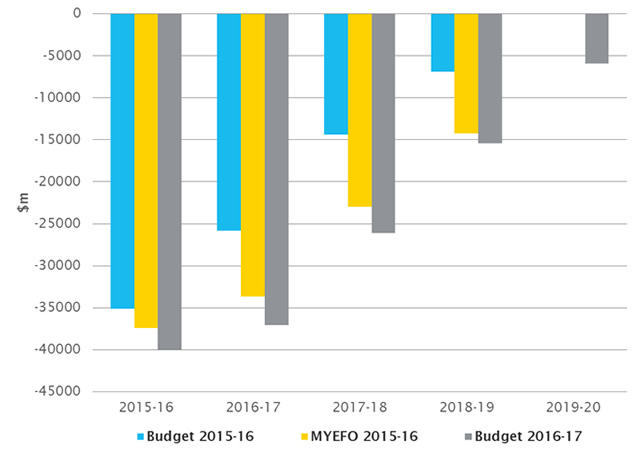

Figure 3 provides a snapshot of how the outlook for the

underlying cash balance has changed since Budget 2015‑16. Over the four

years to 2018‑19, it has worsened since last year’s budget. While the

forecasts and projections still show a consistent pattern on gradually

declining cash deficits, in dollar terms, the deficits in 2018‑19 are now

projected to be more than twice as large as they were in the 2015-16 Budget.

Figure 3:

Revisions to the underlying cash balance ($m)

Source: Australia Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 3, Table 5, p. 3-24.

In last year’s budget, the size of the accumulated budget

deficits over the four years to 2018‑19 was $82.3 billion. This

figure was revised up in MYEFO 2015‑16 to $108.3 billion and in

the 2016–17 Budget to $118.6 billion. This suggests that since last year’s

budget there has been slippage over the four years to 2018‑19 of

$36.3 billion.

The bulk of this slippage is due to parameter and other

variations (Table 8). The cumulative impact of parameter and other

variations over the four years to 2018‑19 has been to worsen the fiscal

outlook by around $28.2 billion (78 per cent of the overall

slippage). The cumulative impact of policy changes over this period has been to

worsen the fiscal outlook by around $8.1 billion (22 per cent of

the overall slippage).

Table 8: The effect of

policy and parameter variations on the underlying cash balance

| |

Changes from 2015–16 Budget to

2015–16 MYEFO

$m |

Changes from

2015–16 MYEF to

Budget 2016–17

$m |

| |

Policy

decisions |

Parameter

&

other variations |

Policy

decisions |

Parameter

&

other variations |

| 2015-16 |

-2,516 |

231 |

-195 |

-2,352 |

| 2016-17 |

-2,427 |

-5,404 |

-3,070 |

-343 |

| 2017-18 |

302 |

-8,927 |

384 |

-3,484 |

| 2018-19 |

921 |

-8,246 |

-1,494 |

319 |

| Total |

-3,720 |

-22,346 |

-4,375 |

-5,860 |

Source:

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2016–17, 2016, Statement 3, Table 5, p. 3-24.

Focusing just on developments since MYEFO 2015‑16,

the fiscal outlook over the four years to 2018‑19 has worsened by around

$10.2 billion. Policy changes account for $4.4 billion

(43 per cent) and parameter and other variations for

$5.9 billion (57 per cent) of the overall slippage:

- Since MYEFO 2015-16 policy decisions have increased

payments by around $3.1 billion over the four years to 2018‑19 and

decreased receipts by $1.2 billion over the same period.

- Since MYEFO 2015‑16 parameter and

other variations have reduced payments by around $8.5 billion, decreased

receipts by $16.8 billion and decreased net Future Fund earnings by

$2.4 billion. The net effect has been to increase the underlying cash

deficit by $5.9 billion.

Statement 3 of Budget Paper No. 1 includes a

detailed reconciliation of the changes to the projected underlying cash balance

since the 2015‑16 Budget.

The

Commonwealth’s balance sheet

The deterioration in Australia’s short-term fiscal outlook

is reflected in the Commonwealth’s balance sheet (Table 9). In broad

terms, larger projected cash deficits over the four years to 2018‑19 mean

that the Australian Government faces a larger financing requirement and will

need to borrow more.

Net

financial worth

The primary indicator of fiscal sustainability articulated

in the Government’s medium-term fiscal strategy is net financial worth (that

is, total financial assets minus total financial liabilities). It provides a

broad measure of the Government’s assets and liabilities as it includes both

the assets of the Future Fund and the superannuation liability the Future Fund

is intended to offset. One of the goals of the Government’s medium-term fiscal

strategy is to strengthen the Government’s balance sheet by improving net

financial worth over time.

The short-term outlook for the Commonwealth’s net financial

worth has deteriorated over the past year. It was projected to be

-$417.8 billion (-21.6 per cent of GDP) in 2018‑19 at the

time of Budget 2015‑16. This declined to -$438.2 billion

(-23 per cent of GDP) at the time of MYEFO 2015‑16; and

declined further to -$454.3 billion (-24 per cent of GDP) in this

year’s Budget.

Table 9: Net financial

worth, net debt and net interest payments ($b and %)

| |

2014-15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

| |

Net

financial worth |

| Budget 2015–16

($b) |

-350.1 |

-383.5 |

-406.0 |

-415.2 |

-417.8 |

|

| Budget 2015–16 (% GDP) |

-21.8 |

-23.2 |

-23.3 |

-22.6 |

-21.6 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16

($b) |

-421.1 |

-377.5 |

-409.7 |

-427.3 |

-438.2 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 (% GDP) |

-26.2 |

-22.9 |

-23.7 |

-23.6 |

-23.0 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 ($b) |

-421.1 |

-387.9 |

-427.2 |

-445.2 |

-454.3 |

-455.8 |

| Budget

2016–17 (% GDP) |

-26.2 |

-23.5 |

-24.8 |

-24.6 |

-24.0 |

-22.9 |

| |

Net

debt |

| Budget 2015–16

($b) |

250.2 |

285.8 |

313.4 |

323.7 |

325.4 |

|

| Budget 2015–16 (% GDP) |

15.6 |

17.3 |

18.0 |

17.6 |

16.8 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16

($b) |

238.7 |

278.8 |

316.5 |

336.4 |

346.6 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 (% GDP) |

14.8 |

16.9 |

18.3 |

18.5 |

18.2 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 ($b) |

238.7 |

285.7 |

326.0 |

346.8 |

356.4 |

355.1 |

| Budget

2016–17 (% GDP) |

14.8 |

17.3 |

18.9 |

19.2 |

18.8 |

17.8 |

| |

Net

interest payments |

| Budget 2015–16

($b) |

10.9 |

11.6 |

11.9 |

12.3 |

13.0 |

|

| Budget 2015–16 (% GDP) |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16

($b) |

10.9 |

11.2 |

11.9 |

12.7 |

13.5 |

|

| MYEFO 2015–16 (% GDP) |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

| Budget 2016–17 ($b) |

10.9 |

12.0 |

12.6 |

13.4 |

14.2 |

14.2 |

| Budget

2016–17 (% GDP) |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.7 |

Source:

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2015–16, 2015, Statement 10, Table 5, p. 10-14,

Table 8, p. 10-19; S Morrison (Treasurer) and M Cormann (Minister for

Finance), Mid-year

economic and fiscal outlook 2015–16,

2015, Appendix D, Table D4, p. 297, Table D7, p. 301;

Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1 2016–17, 2016, Statement 10, Table 4, p. 10-12,

Table 7, p. 10-16.

General

government sector net debt

Australian Government general government sector net debt is equal

to the sum of deposits held, government securities, loans and other borrowing,

minus the sum of cash and deposits, advances paid and investments, loans and

placements:

- At the time of last year’s budget net debt was

forecast to be $325.4 billion by 2018‑19 (16.8 per cent of

GDP). This projection was revised up in MYEFO 2015‑16 to

$346.6 billion (18.2 per cent of GDP) and to $356.4 billion

(18.8 per cent of GDP) in the Budget.

- Net debt as a percentage of GDP was projected to

peak in 2016‑17 in last year’s budget at 18 per cent of GDP. It

is now projected to peak a year later in 2017‑18 at

19.2 per cent of GDP.

- Statement 6 of Budget Paper No. 1 includes a reconciliation of changes in net

debt from MYEFO 2015‑16 to the Budget.

General

government sector net interest payments

Australian government general government sector net interest

payments are equal to the difference between interest paid and interest receipts:

- At the time of last year’s budget, net interest

payments were projected to be $13.0 billion (0.7 per cent of

GDP) in 2018‑19. This was revised up slightly in MYEFO 2015‑16 to

$13.5 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP) and to $14.2 billion

(0.8 per cent of GDP) in this year’s Budget.

- The Budget assumes a weighted average cost of

borrowing of around 2.5 per cent for future issuance of Treasury Bonds in the

forward estimates period, compared with around 2.7 in MYEFO 2015‑16.

[7]. Australian

National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, December 2015,

op. cit.

[12]. Budget

Paper No. 1, op. cit., p. 2-19.

[13]. Statement

on Monetary Policy, op. cit., p. 62.

[15]. Measures of

underlying inflation focus on persistent or generalised movements in prices by

excluding price movements which reflect temporary, highly volatile or policy

factors. In this way measures of underlying inflation gauge price

movements that are predominantly due to market forces and have implications for

future inflation.

[20]. Statement

on Monetary Policy, op. cit., p. 62.

[22]. Budget

Paper No. 1, op. cit., p. 2-6.

[25]. How

central banks meet the challenge of low inflation, op. cit.

[29]. Statement

on Monetary Policy, op. cit., p. 5.

[31]. Statement

on Monetary Policy, op. cit., p. 59.

[32]. Budget

Paper No. 1, op. cit., p. 2-9.

[33]. Australian Government, Budget 2016–17: Overview, 3 May 2016, p. 2.

[34]. Budget

Paper No. 1, op. cit., p. 2-27.

[36]. Ibid., pp. 7-3 to 7-22.

[42]. Budget

Strategy and Outlook: Budget Paper No. 1: 2015–16, op. cit., p. 3‑3.

[43]. Budget

Paper No. 1, op. cit., p. 3-10.

[49]. Statement

on Monetary Policy, op. cit., p. 60.

[50]. Budget

Paper No. 1, op. cit., p. 3-12.

All online articles accessed May 2016.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Entry Point for referral.