Issue

Australians spend over $7.6 billion a year on dental

services, which are not covered by Medicare. Nearly a fifth of Australians have

delayed or avoided necessary dental care due to cost. This scenario has led to

increased calls for the Australian Government to provide additional funding or add

dental services to Medicare. Historically, there have been contested views

about Commonwealth funding to improve dental service affordability and access,

and the way forward is still being debated.

Key points

- Most

dental services in Australia are funded by individuals, with some assistance

from private health insurance.

- State

and territory governments deliver targeted public dental services to children

and concession card holders.

- The

Australian Government contributes funding towards basic dental services for

eligible children. It also supports state and territory dental services

through public hospital funding and indirectly through the private health

insurance rebate.

- The

history of dental funding reform is largely a sustained debate over the

Commonwealth’s role and includes discussion about universal versus targeted

approaches.

- While

cost is a major barrier to reform, opportunities for targeted approaches

exist, such as for seniors and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Context

Who pays (and can’t pay) for dental services?

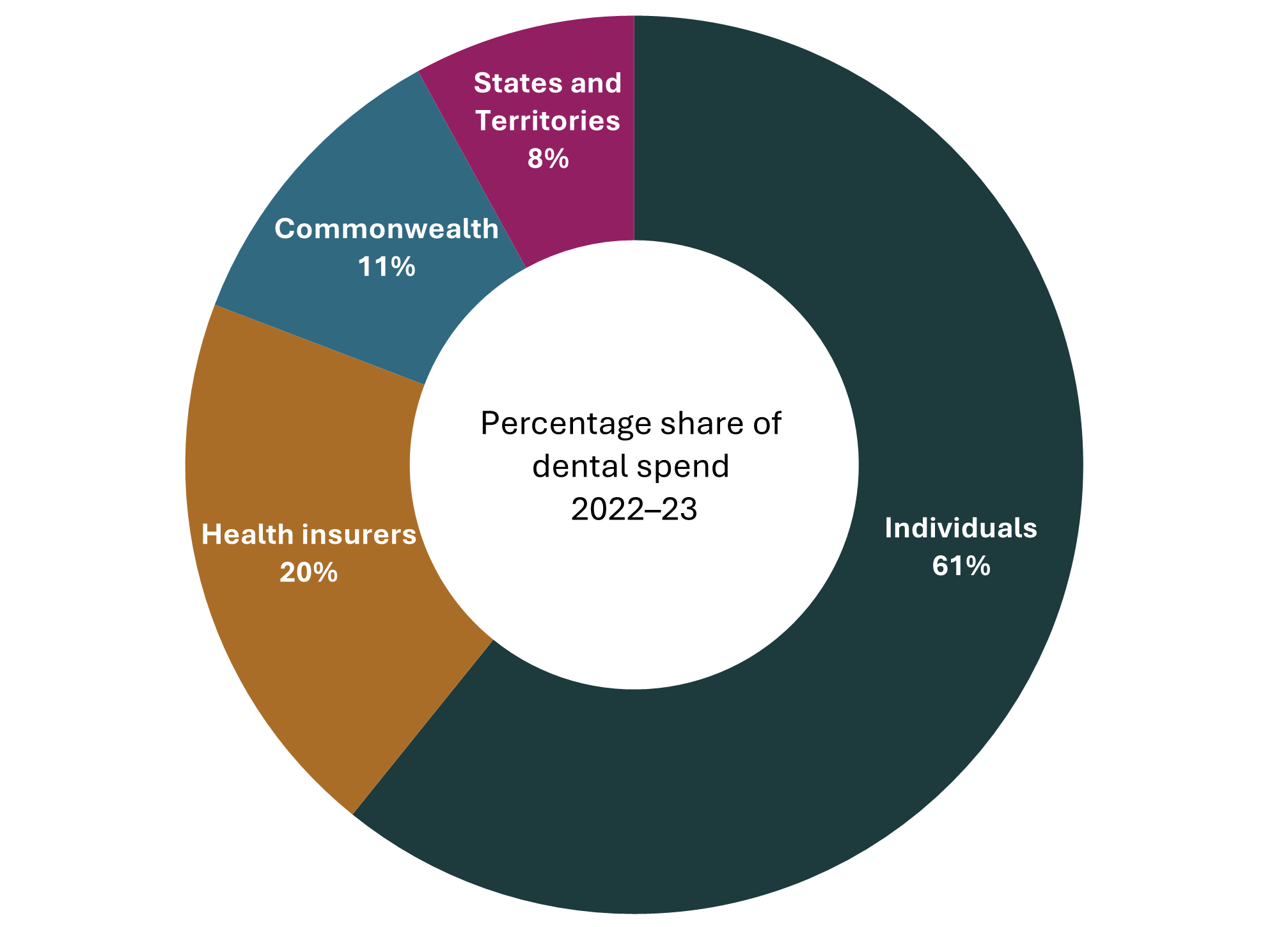

In 2022–23, $12.5 billion was spent

on dental services in Australia. Individuals spent more than $7.6 billion,

health insurers close to $2.5 billion, the Commonwealth nearly $1.4 billion,

and state and territory governments nearly $1 billion (Figure 1).

Concern about dental

affordability and access is long-standing. The Australian

Bureau of Statistics reports that in 2023–24, 17.6% of people delayed or

avoided seeing a dental professional due to cost (Table 14.3). This was

exacerbated for people in areas of most socio-economic disadvantage (27.3%) or

with a long-term health condition (20.8%) [see Table 15.2].

Figure 1 Percentage share of dental spend

2022–23

Source: Parliamentary Library graph using data from the Australian

Institute of Health and Welfare.

Current arrangements for Commonwealth funding of

dental services

Table 1 outlines key current Commonwealth dental funding

arrangements.

Table 1 Selected Commonwealth

funding for dental services

| Activity |

Description |

Mechanism |

Level of

funding |

Number of

people benefitting |

|

Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS)

|

The

Commonwealth provides means-tested capped benefits (up to $1,132a over 2 years) for basic dental services (excludes orthodontic, cosmetic or in-hospital

dental services) delivered by private or public providers to children aged

0–17 years.

|

Dental Benefits Act 2008

Dental Benefit Rules 2014

|

Estimated

$325.9 million in 2025–26

(p. 76)

|

In 2021,

2,607,949 children were eligible; 959,517 used the CDBS (36.8%) (p. 13).

|

|

Funding to the states and

territories for adult public dental services

|

The Commonwealth provides

funding to the states and territories to support the delivery of additional

public dental services to eligible adult dental patients.

|

Federation Funding Agreement – Health – Public

Dental Services for Adults 2023–25b

|

$107.8 million in 2025–26c (p. 43)

|

Up to an additional

180,000 eligible dental patients are funded per year (based on 2023 figures).

|

|

Contribution to public hospital funding

|

The Commonwealth

contributes funding to states and territories for each episode of public

hospital dental services (admitted and outpatient).

|

National Health Reform Agreement

|

Estimated $178.8 million

in 2020–21; $125.4 million in 2021–22 (calculated from Table 1)

|

Not available.

|

|

Private health insurance (PHI) rebate

|

The Commonwealth provides

an income-tested rebate to help meet the costs of premiums for hospital, general

treatment (including dental) and ambulance policies.

|

Private Health Insurance Act 2007

|

Estimated $825 million in

PHI rebate paid out in dental claims in

2022–23 (Table A3)

|

Precise numbers of people

accessing dental rebates are not routinely published, but 55.1% of the population (more than 15 million people) have general

treatment (extras) cover. Singles earning above $158,000 and families earning above $316,000 are not eligible for any

rebate.

|

|

Rebates for veteran gold and white card

holders

|

The Commonwealth provides

rebates to providers via the Veterans dental schedules. Veteran Gold Card holders receive treatment based on clinical need, and Veteran

White Card holders receive treatment in relation to accepted

disabilities.

|

National Health Act 1953

|

Estimated $90 million in

2022–23 (Table A3)

|

Precise numbers of

veterans accessing dental rebates are not routinely published. As at September 2023 there were 104,543 Gold Card holders and 89,273 White Card holders.

|

a Benefit

cap if 2025 is the first year of the 2-year period. The cap amount is

indexed yearly on 1 January.

b The 2025–26

Budget provided $107.8 million in 2025–26 to extend the existing agreement

to 30 June 2026 (p. 52). An amended agreement has not been published.

c Under successive

agreements, annual funding has remained largely constant since 2017–18.

The Medicare Benefits Schedule funds some limited dental-related

services, such as treating patients

with an eligible

cleft and/or craniofacial condition. In 2024, this incorporated

approximately $9.6

million in benefits. The Commonwealth also

provides grants (pp. 2–3) to:

- Royal

Flying Doctor Service dental outreach services (around $5.8 million per year),

- population

health dental research studies (estimated $2.3 million between 2023–24 and

2025–26)

- some

targeted funding for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

History of Commonwealth funding for dental services

Over the past 50 years, Australian governments have

introduced and abolished a range of dental initiatives. In 1946 a constitutional

change gave the Commonwealth powers to legislate with respect to providing

dental services. However, successive Australian governments have generally

regarded public dental services as state and territory responsibilities:

- The

1973–74 Federal Budget provided

funding for a national school dental scheme (p. 78) but it was subsequently

abolished in the 1981–82

Budget.

- Dental

services were excluded from Medicare and its predecessor, Medibank, which

commenced in 1975. Former Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Secretary, John Menadue, reported

this was due to cost and anticipated resistance from the dental profession.

- In

1994 the Federal Government introduced the Commonwealth

Dental Health Program, providing funding to the states and territories

towards emergency and general public dental services. This was abolished from 1

January 1997 on the basis that the program had

met the original target of 1.5 million people (p. 75).

- The

2004–05

Federal Budget included an Allied Health and Dental Health Care Initiative as

part of the MedicarePlus package (p. 208). This provided for up to 3 annual dental

consultations for those with dental problems significantly exacerbating chronic

medical conditions. In response to low

take-up rates, the 2007–08 Budget expanded benefits (pp. 9–10).

- In

June 2008 the Government legislated a Medicare

Teen Dental Plan; however, the Senate

blocked its efforts to replace the previous Commonwealth dental scheme with

a new

promised program. The Coalition supported the existing scheme, while the

Greens called for additional government funding for those with chronic

illnesses (p. 2). An eventual

compromise led to a National Partnership Agreement, providing additional

funding to the states and territories, and an expanded CDBS replacing the Teen

Dental Plan. These negotiated reforms reflect the Commonwealth dental

commitments in place today.

- In

2016, the Federal Government proposed a new

Child and Adult Public Dental Scheme for concession card holders to replace

the CDBS and National Partnership Agreement. The Commonwealth would contribute

40% of funding (capped to CPI growth and population after an initial transition

period) but the states and territories would be responsible for program

delivery (pp. 102–103). Following criticism from dental

stakeholders

and the Opposition,

and a lack of support from some states, in December 2016 the Health Minister announced

the proposal would not proceed.

Reform debate

Brief history of reform proposals

Alongside these practical reform challenges have been the

more conceptual arguments regarding the Commonwealth’s role in funding dental

services. Some advocate for dental services to be a

universal entitlement incorporated into Medicare. Others have argued for more

targeted schemes providing free or low-cost dental services based on need.

Several inquiries have explored extending Medicare to

include dental treatment based on universal access principles. These include

the Layton

inquiry in 1986, 2 Senate inquiries (in

1998 and 2003)

– and a House of Representatives inquiry

in 2006. The most recent is the 2023 Senate Inquiry on the Provision

of and Access to Dental Services in Australia.

Proposals for targeted access to dental services involve

limited free or subsidised access based on means-testing or population features

such as age. The CDBS uses this targeted approach, which provides a potential

delivery model.

Examples of targeted access proposals include the

Australian Greens’ 2011

plan to phase in Medicare-funded services over 5 years, giving priority to

children and teens, the elderly, low income earners and those with chronic

diseases. The Greens reannounced versions of this policy in 2013,

2016

and 2019.

The 2012 report of the National

advisory council on dental health canvassed a range of targeted

arrangements, and several Senate inquiries have also recommended targeted

approaches, including in 1998

and 2023.

The Royal

Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (Recommendation 60) and the

2023 Senate

inquiry (Recommendation 13) recommended a Seniors Dental Benefit Schedule

modelled on the CDBS.

Universal access proposals to basic dental services, such as

check-ups and fillings, have included:

What now?

The costs of increasing public access to primary dental

services are regularly cited as a major barrier to reform in Australia. These

costs are significant, with the Parliamentary Budget Office estimating

that including dental

in Medicare could cost $45 billion over 3 years from 2025–26. Additionally,

a specific seniors

scheme across 10 years from 2024–25 could cost $15.6 billion capped or

$19 billion uncapped (pp. 17–20).

During the 2025 election campaign, Prime Minister Anthony

Albanese stated that the argument against fully including dental into Medicare

was ‘economic’

(pp. 9–10). Minister for Health and Ageing, Mark Butler, expanded

on this at a press club debate (pp. 12–13):

…although Labor has in its platform

and [sic] ambition to bring dental into Medicare more broadly, we don't have

the capacity to do that in the immediate future. … [W]hen we were last in

government, we introduced a Medicare style funding system for kids from

families receiving family tax benefit. That's working terrifically well...

There is a recommendation to consider an equivalent style scheme for seniors

that would be interesting to look at. Very expensive, but interesting to look

at.

Commonwealth, state and territory health officials have also

been discussing dental funding reform, including options

for public dental arrangements that better meet the needs of seniors and

Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander peoples (p. 2).

Debate continues on the future

of dental funding reform, including on whether to pursue universal coverage or

continue refining targeted schemes, and how to best address growing concerns about

access to essential dental care for vulnerable groups.