Issue

Australia’s long-term economic prosperity is under threat

due to a sustained slowdown in productivity growth. Structural challenges have

exacerbated this, and the policy responses to COVID-19, while protecting jobs

and businesses, may have hindered longer-term productivity growth. Renewed

reform and innovation could reverse this trend.

Key points

- Between

2010–20, Australia recorded its weakest productivity growth in 60 years.

- Reduced

multifactor productivity (MFP) was the largest contributor to this slowdown,

reflecting reduced efficiency in combining labour and capital.

- COVID-19

policy responses, such as JobKeeper, may have impeded productivity-enhancing

reallocation of labour and capital.

- Modest

productivity growth improvements can have major long-term economic benefits,

including significantly higher gross domestic product (GDP).

Context

Productivity measures how efficiently inputs (such as

capital and labour) are used to produce outputs (goods and services).

Productivity growth occurs when an economy produces more output with the same

input, maintains output levels using fewer inputs, or a combination of both.

Labour productivity has accounted for over 70% of

Australia’s per capita economic growth over the past 40 years. Australia’s

strong productivity performance in the late 20th century was driven by major

economic reforms.

The Productivity Commission (PC) proposed comprehensive

reform agendas in its 2017 and 2023 reviews. Successive governments have not

made formal responses to the specific review recommendations. The PC is working on 5

‘productivity pillar’ inquiries, with reports due to be delivered to the

Government in late 2025.

The main driver of economic growth

Increasing population, workforce participation and

productivity drive economic growth. In Australia, productivity has historically

been the main driver and key determinant of rising per capita incomes and

living standards. This is achieved through:

-

cheaper goods and services

-

improved quality of goods and services

-

new goods and services which provide a benefit

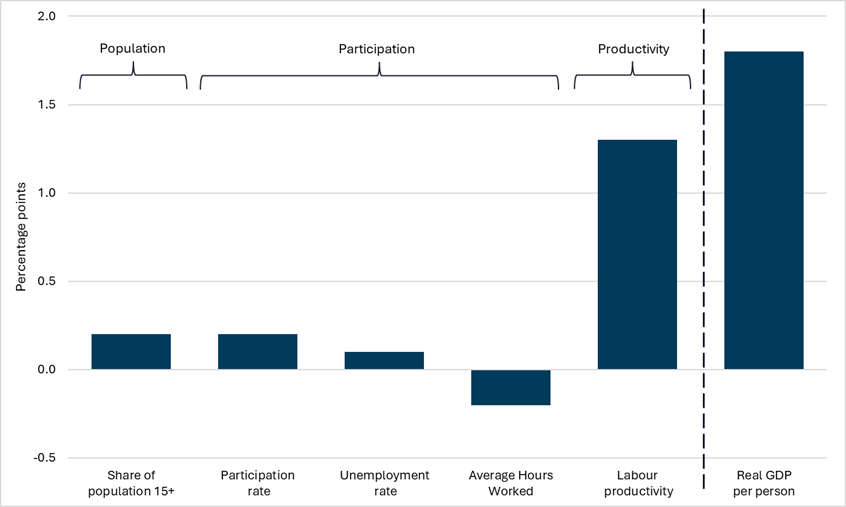

According to the Treasury’s Intergenerational

Report 2023 (2023 IGR), over the past 40 years labour productivity per hour

worked accounted for over 70% of the real GDP growth per person (Figure 1

below). However, average productivity growth over the decade to 2020 was the

slowest in 60 years (2023 IGR, p. 81). Other advanced economies have also

experienced falling productivity growth, with the 2023 IGR suggesting there are

shared causal factors such as:

- reduced

competition

- slow

uptake of technology adoption

- growing

service sectors and

- low

human capital accumulation.

Figure 1 Drivers of real GDP per person growth past 40 years to

2023

Source: Treasury, Intergenerational

report 2023: Australia’s future to 2063, p. 25.

How is productivity measured?

Box 1 below outlines some key productivity measurement

concepts.

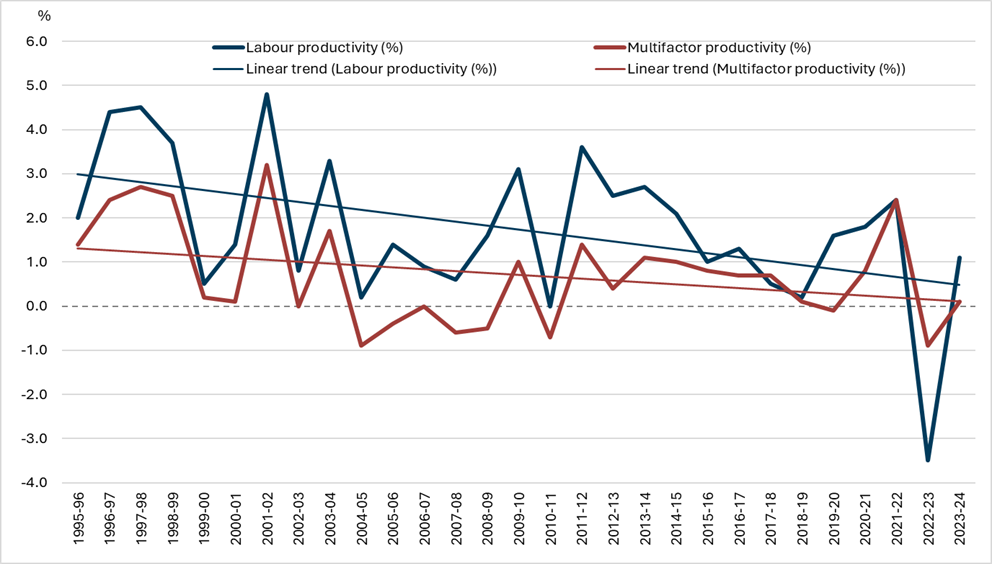

According to annual ‘market sector’ LP and MFP changes since

1995–96 (Figure 2), labour productivity grew 1.1% and MFP rose 0.1% in 2023–24.

Figure 2 Market sector, productivity growth – hours worked basis

Source: ABS, Estimates of Industry Multifactor

Productivity, 2023–24,

released 22 January 2025.

While productivity measures would ideally cover all economic

activities, they currently incorporate only three‑quarters of the economy.

Sectors with measurement limitations comprise the ‘non‑market’ sectors

and ownership of dwellings.

‘Non‑market’ sectors provide government-funded outputs

to consumers free of charge or at non‑market prices. Examples include Public

Administration and Safety, Education and Training, and Health Care and Social

Assistance. Without meaningful price signals, measuring

MFP is very difficult and so the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) does

not produce MFP data for these sectors. Ownership of dwellings is also excluded

because no employment is associated with it.

Importantly, cyclical factors can cause large year‑to‑year

productivity changes. For example, in economic downturns firms tend to retain

skilled labour they will still need in the future. Such labour (and related

capital) may only be partially utilised, reducing annual productivity.

Accordingly, changes in productivity growth are best observed over longer

‘growth cycles’ rather than through annual movements.

Productivity growth in Australia has slowed

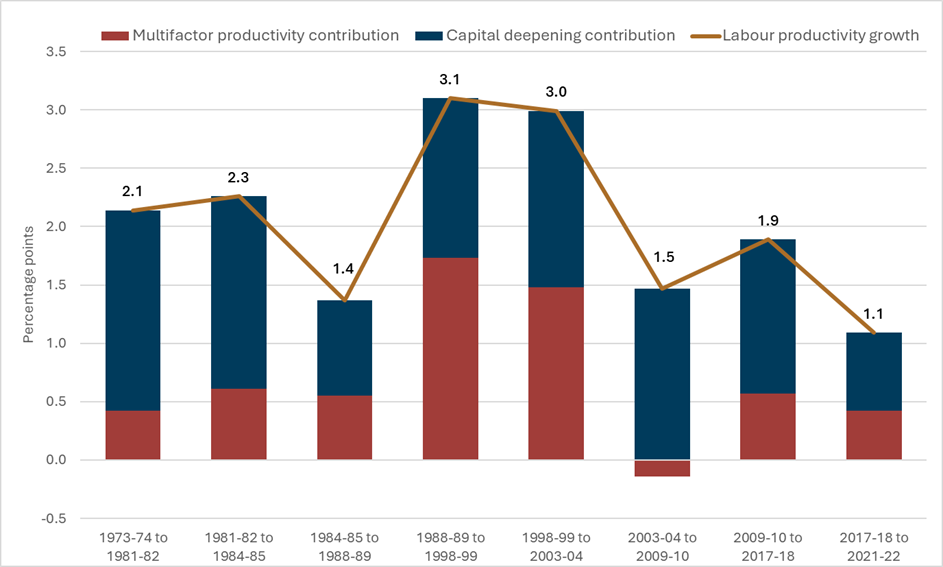

Since reaching 3% in the growth cycles spanning the late

1980s to early 2000s, Australia’s aggregate LP growth has consistently been below

2% and was just 1.1% in the latest cycle (Figure 3). While capital deepening

has continued to grow at a reasonable rate, MFP growth is

now lower, and in 2003–04 to 2009–10 actually went backwards.

Figure 3 Market sector labour productivity decomposition –

average growth per cycle

Source: ABS, Estimates

of Industry Multifactor Productivity, 2023–24, released

22 January 2025.

According to the PC,

some of the weakness during this time is explained by the mining boom, which

led to lower measured productivity growth in 2 ways:

- Substantial

infrastructure (and therefore a lengthy construction period) was required

before materials were mined. The multiple-year lag meant that capital and

labour were being used without immediately generating materials that could be

sold, lowering measured productivity.

- High

commodity prices meant it become profitable to mine poorer quality reserves,

that required more capital and labour for a given amount of mined material.

For the more recent growth cycles, the 2023

IGR has similarly cited declining competition, economic dynamism and

regulatory reform as structural causes for the productivity growth slowdown.

The COVID-19 pandemic was also

significant, leading to Government policy responses including:

While such policies protected jobs and businesses, as the

economy recovered these measures impeded potentially more productive workforce

changes. Consequently, through prioritising job security and business

continuity, government policy responses may have reduced potential productivity

growth.

How can Australia improve its labour productivity?

What has helped previously

The superior productivity performance from the late 1980s

through to the early 2000s is widely attributed to successive governments’ microeconomic

and macroeconomic reforms prior to and during this period. These reforms

included:

-

movement towards medium‑term monetary and fiscal policy

frameworks (targeting inflation and a balanced budget over the economic cycle)

-

floating the exchange rate, liberalising capital markets and removing

interest rate controls

-

reduced industry assistance measures and tariffs

-

taxation reform

-

privatising government business enterprises

-

moving from centralised wage determination to enterprise

bargaining

-

establishing the National

Competition Policy.

These reforms opened the economy to foreign competition,

increased capital flows, improved the efficiency and flexibility of domestic

markets and delivered greater macroeconomic stability.

Looking to the future

More recently, the Productivity Commission has released two

5-year Productivity Reviews; the first in 2017 and the second in 2023.

The Productivity Commission’s first review, Shifting the

dial, recommended several options for how governments can positively

influence labour productivity growth, including:

-

making Australia’s health system more outcome-oriented, rather

than paying for services

-

creating a high quality and adaptive education and training

system and ensuring a

well-functioning labour market -

improving town and city functionality through improved public

infrastructure, road funding and investment, planning and land use policies,

and access to housing

-

improving market efficiency through improved competition and regulatory

frameworks

-

better intergovernmental relations and public finance management to

develop stronger policy development and delivery capabilities.

Although the Australian Government customarily responds to

Productivity Commission recommendations, this did not occur for this inquiry.

The Commission’s second 5-year

Productivity Inquiry included 71 recommendations, within 5 ‘reform

pillars’.

While the Australian Government has not issued a formal

response to the specific recommendations, the Treasurer did publish a media

release discussing generalities. He then commissioned

the Productivity Commission to undertake a series of inquiries into how to

boost productivity across the 5 ‘reform pillars’:

The terms

of reference for the inquiries noted they should ‘identify the highest

priority reform areas under each of the five pillars’ and emphasise

regulatory reform. The interim reports for these inquiries are expected to

be released in July or

August 2025.

Improved productivity growth has the starkest impact when

looking at the long‑term implications. For example, The 2023

IGR assumed productivity growth of 1.2%; however, just a 0.3% increase to

this would create a projected 9.5% lift to GDP in 2062–63 (p. 23).

Conclusion

The Productivity Commission is currently working on further

inquiries to assist with productivity, including workforce adaptability,

digital innovation, market dynamism, non-market sector efficiency, and

cost-effective climate transition. The government’s response to these

recommendations will be critical to reversing the productivity slowdown.