7

December 2018

PDF version [429KB]

Joanne

Simon-Davies

Statistics and Mapping Section

Introduction

Compared with 100 years ago, Australians today are older, have fewer

children, are more likely to live in urban areas, and are more likely to be

born overseas in countries other than the United Kingdom. Stimulated by the

gold rushes of the 19th century, Australia's population had reached nearly four

million by Federation in 1901. For the first part of the 20th century, natural

increase was the main contributor to population growth, as better living

conditions saw births outnumber deaths. Following the end of World War II in

1945, the total fertility rate grew and Australia actively embarked on an

immigration program to boost the population.

The rate of population growth has increased since the mid-2000s.

Overseas migration is now the main driver of this, making up about 64 per cent

of population growth (2017). By 2018, Australia's population had increased to 25

million people.[1]

This guide provides an overview of the drivers of Australia’s growing population

and an introduction to the key concepts and terminology used.

Counting the Australian population

There are two ways the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) determines

the size and characteristics of the population: the five-yearly Census of

Population and Housing (Census) and quarterly estimates of the resident

population. The Census can be counted by place of enumeration or by place of

usual residences:

- Census counts by place of

enumeration are a count of every person

in Australia on Census Night, based on where they were located on that night.

This may or may not be the place where they usually live. This count excludes

Australian residents who were out of the country on Census Night and overseas

diplomatic personnel and their families in Australia.

- Census counts by place of usual

residences are a count of people

based on the place where they usually live. This information is determined from

responses to the question of usual residence on the census form. Visitors to an

area are not included in the usual residence Census count.

- Estimated resident population (ERP) is the official estimate of the Australian

population and based on Census counts by place of usual residence, to which are

added the estimated Census net undercount (those

people missed on Census night[2])

and the number of Australian residents estimated to have been temporarily

overseas on Census night. Short term overseas visitors in Australia on Census

night are excluded in this calculation. Post-Census ERP is obtained by adding

to the estimated population at the beginning of each period the components of

population—natural increase and net overseas migration.

Components of population growth

As mentioned above, there are two components to estimating

population growth:

- Natural increase is the excess of births over deaths (measured by

fertility rates and life expectancy).

- Net overseas migration (NOM)[3] is the

difference between incoming migrants and outgoing migrants[4]. Net overseas

migrant arrivals are all arrivals who are in Australia for a total of 12 months

or more during a 16-month period. These people are added to the ERP. Net

overseas migrant departures are people counted in the ERP, and then removed

after they have been outside of Australia for 12 months or more during a

16-month period. Short-term tourists in Australia for less than 12 months are

not included in the count; however international students who are in Australia

studying for more than 12 months are included. Data provided by the Department

of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) is used by the ABS to calculate the official NOM

estimates each quarter.

According to the ABS:

The

official measure of the population of Australia is based on the concept of

usual residence. It refers to all people, regardless of nationality,

citizenship or legal status, who usually live in Australia, with the exception

of foreign diplomatic personnel and their families. It includes usual residents

who are overseas for less than 12 months over a 16-month period. It excludes

overseas visitors who are in Australia for less than 12 months over a 16-month

period.[5]

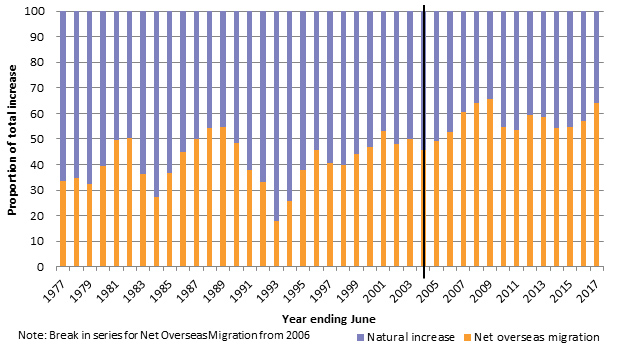

The relative contribution these two components make has changed

considerably over time, as can be seen in Figure 1. During 1976–1977, natural

increase represented 66.6 per cent of Australia’s population growth and NOM 33.4

per cent; by 2016–17 natural increase represented only 36.0 per cent of Australia’s

population growth with NOM at 64.0 per cent. Interestingly, the increase in NOM

in recent years has not been caused by an increase in permanent settlers.

Rather it has been driven by people staying in Australia on long-term temporary

visas, such as overseas students and temporary skilled migrants

(see Table 1 on page 5).

Figure 1 Components of change, 1976–77 to 2016–17

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australian Historical Population Statistics, cat no. 3105.0.65.001 (Population size and growth) and

Australian Demographic Statistics, March 2018, cat no. 3101.0 (table 1)

It is important to note that whilst natural increase is largely outside

of government control, migration (NOM) can be influenced by a range of factors

including government policy (in particular migration policy), the state of the

Australian economy and labour market, and the existing patterns of settlement.

For further information on Australia’s estimated population: ABS Australian

Demographic Statistics, cat no. 3101.0.

Population growth in Australia

Since Federation, Australia’s population has varied from periods

of very high growth to periods of slow growth as can be seen in Figure 2.

During World War 1, there was negative population growth (-0.9 per cent in

1915–16) due to soldiers going overseas; emerging from World War 1, the

population grew rapidly (3.3 per cent in 1918–19) followed by a considerable

drop during the Great Depression of the 1930s (falling to 0.7 per cent in 1933–34).

Following World War II, annual growth reached 3.4 per cent in 1949–50 and

peaked at 4.5 per cent in 1971. During this period (early 1950s to early 1970s),

average annual growth was 2.2 per cent. After a relatively slow growth period during

the 1980s and 1990s, Australia’s population growth rate increased again in the mid-2000s

peaking in 2008–09 at 2.1 per cent. In 2016–17, the growth rate was 1.7

percent.

It is important to note that Australia’s population growth varies

widely across states and territories and sub-regions. In general, Australian

cities have grown strongly whilst growth in regional areas has been mixed. Over

the last decade, migration has contributed particularly strongly to population

growth in Sydney, Perth and Melbourne. Regional population growth is discussed

in more detail later in this Quick Guide.

Figure 2 Australia's population growth, 1901–02 to 2016–17

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Australian Historical Population Statistics, cat no. 3105.0.65.001 (Population size and growth) and

Australian Demographic Statistics, March 2018, cat no. 3101.0 (table 1)

Components of migration

A range of visa categories contribute to NOM, including temporary visas

(i.e. students and long- term visitors), permanent settlers plus Australians

returning home or leaving the country.

According to the ABS:

Home Affairs manages and grants visas each year and it is important

to note there is a difference between when Home Affairs issues a visa and when

and how they may impact on NOM and therefore Australia's estimated resident

population. For example, for many visas there can be a lag between a visa being

granted and the actual use of that visa by the applicant on entering Australia.

Also, some travellers who have been granted permanent or long-term temporary

visas may end up staying in Australia for a short period of stay or not at all.

In addition, travellers may also apply for and be granted a different visa

whilst in Australia or overseas. However, without an additional border crossing

within the reference quarter to capture a traveller's change of visa, the NOM

system is unable to show these occurrences.[6]

In short, the ABS cannot account for the transition between

visa categories after arrival such as a student moving from a temporary to

permanent visa.

Table 1 provides a breakdown of visa categories by NOM and clearly

shows temporary visa holders were the main contributors to NOM in both 2006–07

and in 2016–17 financial years (61.5 per cent and 70.7 per cent respectively).

Table 1 Net overseas migration (NOM) by visa category

(a), 2006–07 and 2016–17 (b)

| Visa category |

2006-07 |

2016-17 |

| no. |

% |

no. |

% |

| Temporary visas |

143,090 |

61.5 |

185,450 |

70.7 |

| Vocational Education

and Training sector |

16,600 |

7.1 |

4,530 |

1.7 |

| Higher education

sector |

41,920 |

18.0 |

75,550 |

28.8 |

| Student other |

19,730 |

8.5 |

23,920 |

9.1 |

| Temporary work skilled

(subclass 457) |

26,470 |

11.4 |

16,630 |

6.3 |

| Visitor |

25,850 |

11.1 |

53,710 |

20.5 |

| Working Holiday |

16,980 |

7.3 |

24,190 |

9.2 |

| Other temporary visas |

-4,450 |

-1.9 |

-13,060 |

-5.0 |

| Permanent visas |

79,810 |

34.3 |

85,250 |

32.5 |

| Family |

27,990 |

12.0 |

24,330 |

9.3 |

| Skill |

40,400 |

17.4 |

37,780 |

14.4 |

| Special Eligibility

and humanitarian |

12,310 |

5.3 |

23,760 |

9.1 |

| Other permanent visas |

-890 |

-0.4 |

-610 |

-0.2 |

| New Zealand Citizen

(subclass 444) |

28,950 |

12.4 |

5,990 |

2.3 |

| Australian Citizen |

-17,160 |

-7.4 |

-14,250 |

-5.4 |

| Other |

-1,880 |

-0.8 |

50 |

0.0 |

| Total |

232,800 |

100.0 |

262,490 |

100.0 |

(a) Represents the number of visas based

on the visa type at the time of a traveller's specific movement. It is this

specific movement that has been used to calculate NOM. Therefore the number of

visas in this table should not be confused with information on the number of

visas granted by Home Affairs.

(b) Data for 2016-17 is preliminary

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Migration Australia 2016-17, cat no. 3412.0 (Table 2.3 and Table 2.13)

As noted previously, NOM refers to the number of persons

arriving in Australia minus the number leaving and in some instances can result

in a negative value. In Table 1, NOM for Australian citizens (2016–17) is minus

14,250 because there were fewer arrivals (78,890) compared to departures (93,140)

resulting in a negative NOM.

For further information on visa types and NOM: ABS,

Migration Australia, cat no. 3412.0

Country of birth of new arrivals

The composition of the Australian

population has changed considerably since Federation. In 1901, Australia had a

population of 3.8 million people, of whom 22.6 per cent were born overseas. Of

those born overseas (in the top ten countries of birth), the majority were from

the United Kingdom and Ireland (79.7 per cent) with only one country from

Asia—China, representing 3.5 per cent of the population.

By 2016, with a population of 23.4

million, 26.3 per cent were born overseas. While this is not a substantial

increase from 1901, the country profile for those born overseas has changed

significantly. China now represents 8.3 per cent of the overseas-born

population and is one of six Asian countries listed in the top ten countries of

birth. In contrast, the United Kingdom, whilst still number one on the list, now

represents only 17.7 per cent of overseas born.

Australia is now a nation of people from over 190 different

countries and 300 different ancestries.[7]

Table 2 Top 10 countries of birth, 1901, 1954, 2001 and

2016

| Country |

Population |

Share (%) |

|

Country |

Population |

Share (%) |

| 1901 Census |

|

1954 Census |

| 1. United Kingdom (a) |

495 504 |

58.1 |

|

1. United Kingdom |

616 532 |

47.9 |

| 2. Ireland |

184 085 |

21.6 |

|

2. Italy |

119 897 |

9.3 |

| 3. Germany |

38 352 |

4.5 |

|

3. Germany |

65 422 |

5.1 |

| 4. China |

29 907 |

3.5 |

|

4. Poland |

56 594 |

4.4 |

| 5. New Zealand |

25 788 |

3.0 |

|

5. Netherlands |

52 035 |

4.0 |

| 6. Sweden/Norway |

9 863 |

1.2 |

|

6. Ireland |

47 673 |

3.7 |

| 7. South Sea Islands |

9 128 |

1.1 |

|

7. New Zealand |

43 350 |

3.4 |

| 8. British India |

7 637 |

0.9 |

|

8. Greece |

25 862 |

2.0 |

| 9. USA |

7 448 |

0.9 |

|

9. Yugoslavia |

22 856 |

1.8 |

| 10. Denmark |

6 281 |

0.7 |

|

10. Malta |

19 988 |

1.6 |

| Top ten total |

810 113 |

95.5 |

|

Top ten total |

1 070 209 |

83.2 |

| Other |

47 463 |

4.5 |

|

Other |

215 589 |

16.8 |

| Total overseas born |

852 373 |

100 |

|

Total overseas born |

1 285 789 |

100.0 |

| Total population |

3,788,123 |

|

|

Total population |

8 986 530 |

|

| % of Australian born

overseas |

22.6 |

|

% of Australian born

overseas |

14.3 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Country |

Population |

Share (%) |

|

Country |

Population |

Share (%) |

| 2001 Census |

|

2016 Census |

| 1. United Kingdom |

1 036 242 |

25.5 |

|

1. United Kingdom |

1 087 756 |

17.7 |

| 2. New Zealand |

355 765 |

8.8 |

|

2. New Zealand |

518 462 |

8.4 |

| 3. Italy |

218 718 |

5.4 |

|

3. China |

509 558 |

8.3 |

| 4. Viet Nam |

154 830 |

3.8 |

|

4. India |

455 385 |

7.4 |

| 5. China |

142 781 |

3.5 |

|

5. Philippines |

232 391 |

3.8 |

| 6. Greece |

116 430 |

2.9 |

|

6. Viet Nam |

219 351 |

3.6 |

| 7. Germany |

108 219 |

2.7 |

|

7. Italy |

174 042 |

2.8 |

| 8. Philippines |

103 942 |

2.6 |

|

8. South Africa |

162 450 |

2.6 |

| 9. India |

95 455 |

2.3 |

|

9. Malaysia |

138 363 |

2.2 |

| 10. Netherlands Netherlands |

83 324 |

2.1 |

|

10. Sri Lanka |

109 850 |

1.8 |

| Top ten total |

2 415 706 |

59.4 |

|

Top ten total |

3 607 608 |

58.7 |

| Other |

1 648 248 |

40.6 |

|

Other |

2 542 443 |

41.3 |

| Total overseas born |

4 063 954 |

100.0 |

|

Total overseas born |

6 150 051 |

100.0 |

| Total population |

18 769 228 |

|

|

Total population |

23 401 891 |

|

| % of Australian born

overseas

|

21.7 |

|

% of Australian born

overseas |

26.3

|

Source: Australian

Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Census of Population and Housing, 1901, 1954, 2001

and 2016

For all Census years since 1901: Top

10 countries of birth for the overseas-born population since 1901,

Parliamentary Library.

Geographic distribution

Over the past ten years (June 2007 to June 2017), all states

and territories have experienced population growth. Victoria had the largest

growth in absolute numbers (1,168,126 people), followed by New South Wales (1,027,518)

and Queensland (818,134). Tasmania had the smallest growth (28,890).

Table 3 Estimated resident population by States, Territories

and Greater Capital Cities, June 2007 to June 2017

| States and territories |

2007 |

2017 |

2007-2017 ERP change |

| no. |

% |

| New South Wales |

6,834,156 |

7,861,674 |

1,027,518 |

15.0 |

| Greater Sydney |

4,325,525 |

5,132,355

|

806,830

|

18.7 |

| Victoria |

5,153,522 |

6,321,648 |

1,168,126 |

22.7 |

| Greater Melbourne |

3,841,760 |

4,843,781

|

1,002,021

|

26.1 |

| Queensland |

4,111,018 |

4,929,152 |

818,134 |

19.9 |

| Greater Brisbane |

1,958,907 |

2,413,457

|

454,550

|

23.2 |

| South Australia |

1,570,619 |

1,723,671 |

153,052 |

9.7 |

| Greater Adelaide |

1,204,210

|

1,334,167

|

129,957

|

10.8 |

| Western Australia |

2,106,139 |

2,575,452 |

469,313 |

22.3 |

| Greater Perth |

1,628,467

|

2,039,041

|

410,574

|

25.2 |

| Tasmania |

493,262 |

522,152 |

28,890 |

5.9 |

| Greater Hobart |

206,649

|

229,088

|

22,439

|

10.9 |

| Northern Territory |

213,748 |

247,491 |

33,743 |

15.8 |

| Greater Darwin |

116,935

|

148,884

|

31,949

|

27.3 |

| Aust. Capital Territory |

342,644 |

411,667 |

69,023 |

20.1 |

| Total (including Other

Territories) |

20,827,622 |

24,597,528 |

3,769,906 |

18.1 |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016-17, cat no. 3218.0 (revised, August 2018)

Over the same period, Melbourne had the largest growth of

all Greater Capital Cities (1,002,021), followed by Sydney (806,830) and

Brisbane (454,550). Together, these three cities accounted for 60 per cent of total

population growth in Australia.

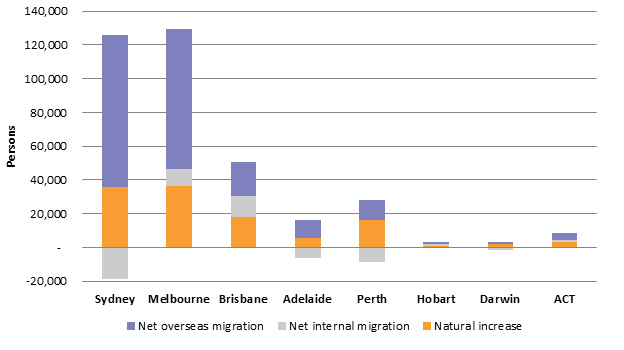

Components of population change:

regional comparison

Population change at the sub-state level can be considered

in terms of three main components: natural increase, net overseas migration and

net internal migration.

Greater Capital Cities

Although the number of people in all capital cities grew in

the year ended June 2017, the proportion each of these components contributed

to population change varied substantially among the cities, as can be seen in

Figure 3 on page 8.

Melbourne experienced the largest population growth of all

capital cities in 2016–17, increasing by 129,500 people. Net overseas migration

was the major contributor, accounting for 64.1 per cent (or 83,000 people); however

Sydney’s NOM contribution was higher than Melbourne’s (83.9 per cent or

90,200). This compares with 60.4 per cent of growth in Perth (11,900) and 40.6

per cent in Brisbane (20,600).

Figure 3 Components of population change: Greater Capital

City comparison, 2016–17

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016-17, cat no. 3218.0 (revised, August 2018)

Rest of state

Just as there is variation in components of population in

Greater Capital Cities (Figure 3), this variation is also evident in ‘Rest of

State’ (Figure 4). Rest of Queensland experienced the largest population

growth, increasing by 33,215 in 2016–17. Net overseas migration was the major

contributor, accounting for 43.8 per cent (or 14,561 people), followed closely

by natural increase accounting for 39.3 per cent of growth (13,046 persons). Interestingly,

Rest of Queensland represented almost half of all natural increase for

non-capital city areas in Australia. This may be explained by the fact that

Queensland is more decentralised than other states and territories.

Net overseas migration was the major contributor in Rest of

New South Wales (14,324 people), a similar number to Queensland (14,561

people), however it accounted for 67.0 per cent of growth in Rest New South

Wales (compared to only 43.8 per cent). In Rest of Victoria, NOM accounted for

37.1 per cent of growth (7,074 people), and 56.6 per cent in Rest of Tasmania

(828 people).

In Rest of Western Australia, population gains from natural

increase (3,698) and NOM were negated by net internal migration losses of

-5,466 persons. Likewise, in Rest of South Australia, whilst there were

increases in NOM (960 people) and natural increase (431 people), there was a

loss of 973 by net internal migration.

Figure 4 Components of population change: Rest of state

comparison, 2016–17

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016-17, cat no. 3218.0 (revised, August 2018)

For further information on regional population estimates Regional

Population Growth, Australia, cat no. 3218.0

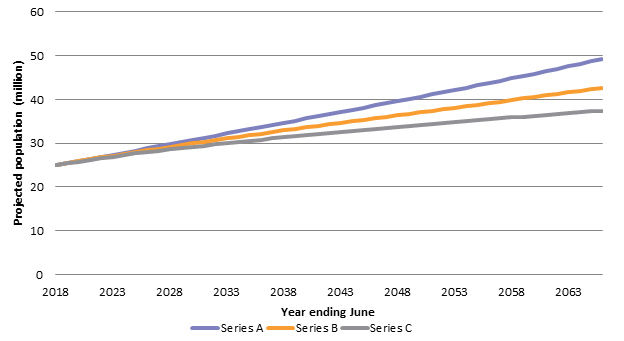

Population projections

In November 2018 the ABS released new population projections

for the period June 2018 to June 2066. These projections have been updated to

reflect the 2016 Census-based population estimates. The ABS stress that these ’projections are not intended to be

predictions or forecasts, but are illustrations of growth and change in the

population that would occur if assumptions made about future demographic trends

were to prevail over the projection period’.[8]

The ABS uses the cohort-component method for producing

population projections. In this method, assumptions made about future levels of

fertility, mortality, overseas migration and internal migration are applied to

a base population (applied by sex and single year of age) to obtain a projected

population for the following year. The assumptions applied, such as overseas

migration and fertility, do not specifically attempt to allow for

non-demographic factors (such as major government policy decisions, economic

factors, catastrophes, wars, epidemics or significant health treatment

improvements) which may affect future demographic behaviour or outcomes. [9]

As future levels of fertility, mortality, overseas migration

and internal migration are unpredictable, two or more assumptions have been

made for each component and projections have been produced for all combinations

of the assumptions. These are intended to illustrate a range of possible future

outcomes, although there can be no certainty that any particular outcome will

be realised, or that future outcomes will necessarily fall within these ranges.

These assumptions can be combined to create 54 sets of

population projections. Three series have been selected from these to provide a

range of projections for analysis and discussion. These series are referred to

as series A, B and C. Series B largely reflects current trends in fertility,

life expectancy at birth and migration, whereas series A and series C are based

on higher and lower assumptions respectively for each of these variables.

This variation in assumptions can be seen in the graph

below. Based on current trends, Australia's population is projected to reach 30

million people between 2029 and 2033.

Under all assumptions, the population of New South Wales is

projected to remain as the largest state with a population of between

approximately 9.0 and 9.3 million by 2027. Victoria is projected to experience

the largest and fastest increase in population; possibly reaching between 7.5

and 7.9 million by 2027.[10]

Figure 5 Population projection: Series A, B and C, 2018

to 2066

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Population Projections, Australia, 2017 (base) - 2066, cat no. 3218.0

For further information: ABS, Population

Projections, 2017-2066, cat no. 3222.0

Glossary

Terms used in this Quick Guide and other reports on this

topic, based on:

(a) Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS), Australian Demographic Statistics, March 2018, cat no. 3101.0

(b) Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS), Migration, Australia, 2016-17, cat no. 3412.0

(c) Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS), Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2016-17, cat no. 3218.0

(d) Australian Bureau of

Statistics (ABS), Population Projections, Australia, 2017 (base) – 2066, cat no. 3222.0

| 12/16 month

rule (a) |

Under a

'12/16 month rule', incoming overseas travellers (who are not currently

counted in the population) must be resident in Australia for a total period

of 12 months or more, during the 16 month follow-up period to then be added

to the estimated resident population. Similarly, those travellers departing

Australia (who are currently counted in the population) must

be absent from Australia for a total of 12 months or more during the 16 month

follow-up period to then be subtracted from the estimated resident

population.

The 12/16 months do not have to be

continuous. The rule takes account of those persons who may have

left Australia briefly and returned, while still being resident for 12 months

out of 16. Similarly, it takes account of Australians who live most of the

time overseas but periodically return to Australia for short periods.

|

| Census (a) |

The complete

enumeration of a population at a point in time with respect to well-defined

characteristics (e.g. Persons, Industry, etc.).

|

| Estimated

resident population (ERP) (a) |

The official

measure of the population of Australia is based on the concept of usual

residence. It refers to all people, regardless of nationality, citizenship or

legal status, who usually live in Australia, with the exception of foreign

diplomatic personnel and their families. It includes usual residents who are

overseas for less than 12 months over a 16-month period. It excludes overseas

visitors who are in Australia for less than 12 months over a 16-month period.

Estimates of the Australian resident

population are generated on a quarterly basis by adding natural increase (the

excess of births over deaths) and net overseas migration (NOM) occurring

during the period to the population at the beginning of each period.

|

| Migrant—International

(b) |

An

international migrant is defined as ’any person who changes his or

her country of usual residence’ (United Nations 1998). The country

of usual residence is the country in which a person lives, that is to say,

the country in which he or she has a place to live where he or she normally

spends the daily period of rest. A long-term international migrant is a

person who moves to a country other than that of his or her usual residence

for a period of at least a year (12 months), so that the country of

destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence.

In Australia, for the purposes of estimating

net overseas migration, and thereby the official population counts, a person

is regarded as a usual resident if they have been (or expected to be)

residing in Australia for a period of 12 months or more over a 16 month

period.

|

| Natural Increase (a) |

Excess of births over deaths.

|

| Net internal migration (c) |

Net internal migration is the net gain or loss of

population through the movement of people within Australia from one region to

another (both interstate and intrastate)

|

| Net interstate

migration (a) |

The

difference between the number of persons who have changed their place of

usual residence by moving into a given state or territory and the number who

have changed their place of usual residence by moving out of that state or territory

during a specified time period. This difference can be either positive or

negative.

|

| Net overseas

migration (NOM) (a) |

Net overseas migration is the net gain or

loss of population through immigration to Australia and emigration from

Australia. Under the current method for estimating final net overseas

migration this term is based on a traveller's actual duration

of stay or absence using the '12/16 month rule'. Preliminary NOM estimates

are modelled on patterns of traveller behaviours observed in final NOM

estimates for the same period one year earlier. NOM is:

- based on an

international traveller's duration of stay being in or out of Australia for

12 months or more over a 16-month period

- the difference

between:

- the number of incoming international travellers

who stay in Australia for 12 months or more over a 16-month period, who are

not currently counted within the population, and are then added to the

population (NOM arrivals) and

-

the number of

outgoing international travellers (Australian residents and long-term

visitors to Australia) who leave Australia for 12 months or more over a

16-month period, who are currently counted within the

population, and are then subtracted from the population (NOM departures).

|

| NOM arrivals

(a) |

NOM arrivals

are all overseas arrivals that contribute to net overseas migration (NOM). It

is the number of incoming international travellers who stay in Australia for

12 months or more over a 16-month period, who are not currently

counted within the population, and are then added to the population.

Under the current method for estimating

final net overseas migration this term is based on a traveller's

actual duration of stay or absence using the '12/16 month rule'.

|

| NOM departures

(a) |

NOM departures

are all overseas departures that contribute to net overseas migration (NOM).

It is the number of outgoing international travellers who leave Australia for

12 months or more over a 16-month period, who are currently

counted within the population, and are then subtracted from the population.

Under the current method for estimating final

net overseas migration this term is based on a traveller's

actual duration of stay or absence using the '12/16 month rule'.

|

| Net

undercount (a) |

The

difference between the actual Census count (including imputations) and an

estimate of the number of people who should have been counted in the Census.

This estimate is based on the Post Enumeration Survey (PES) conducted after

each Census. For a category of person (e.g. based on age, sex and state of

usual residence), net undercount is the result of Census undercount,

overcount, differences in classification between the PES and Census and

imputation error.

|

| Passenger card

(b) |

Passenger cards

are completed by nearly all passengers arriving in Australia. Information

including: country of previous residence, intended length of stay, main

reason for journey, and state or territory of intended stay/residence is

collected.

|

| Permanent

arrivals (settlers) (b) |

Permanent arrivals (settlers)

comprise:

-

travellers who hold

permanent migrant visas (regardless of stated intended period of stay)

- New Zealand citizens

who indicate an intention to migrate permanently on their passenger arrival

card and

-

those who are

otherwise eligible to settle (e.g. overseas born children of Australian

citizens).

This definition of settlers is

used by the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs).

|

| Permanent visa

(b) |

A visa allowing

the holder to remain indefinitely in Australia's migration zone.

|

| Population

growth (a) |

For

Australia, population growth is the sum of natural increase and net overseas

migration. For states and territories, population growth also includes net

interstate migration.

|

| Population

growth rate (a) |

Population

change over a period as a proportion (percentage) of the population at the

beginning of the period.

|

| Population

projections (d) |

The ABS uses

the cohort-component method for producing population projections of

Australia, the states, territories, capital cities and balances of state.

This method begins with a base population for each sex by single year of age

and advances it year by year, for each year in the projection period, by

applying assumptions regarding future fertility, mortality and migration. The

assumptions are based on demographic trends over the past decade and longer,

both in Australia and internationally. The projections are not predictions or

forecasts, but are simply illustrations of the change in population which

would occur if the assumptions were to prevail over the projection period. A

number of projections are produced by the ABS to show a range of possible

future outcomes.

|

| Rebasing of

population estimates (a) |

After each

Census, the ABS uses Census counts by place of usual residence which are

adjusted for undercount to construct a new base population figure for 30 June

of the Census year. Because this new population estimate uses the Census as

its main data source, it is said to be 'based' on that Census and is referred

to as a population base.

|

| Temporary

visas (b) |

Temporary

entrant visas are visas permitting persons to come to Australia on a

temporary basis for specific purposes. Main contributors are tourists,

international students, those on temporary work visas, business visitors and

working holiday makers.

|

| Total fertility

rate (TFR) (a) |

The sum of

age-specific fertility rates (live births at each age of mother per female

population of that age) divided by 1,000. It represents the number of

children a female would bear during her lifetime if she experienced current

age-specific fertility rates at each age of her reproductive life (ages 15 -

49).

|

[1].

Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Australian Historical Population Statistics, 2014, cat no. 3105.0.65.001

[2]. Includes

those who did not complete a Census form.

[3]. In 2006,

the ABS change the definition of NOM, introducing the 12/16 month rule for

calculating NOM. Consequently, this year marks a break

in the series and NOM estimates from earlier periods are not comparable.

[4]. The input

data for calculating NOM is mainly sourced from administrative data provided by

the Department of Home Affairs. Administrative information on persons arriving

in, or departing from, Australia is collected from various sources including

passport documents, visa information, and passenger cards. ABS, Information

Paper: Improvements to the Estimation of Net Overseas Migration, Mar 2018,

cat no. 3412.0.55.004

[5]. ABS, ‘Glossary’, Australian

Demographic Statistics, Mar 2018, cat. no. 3101.0, ABS, Canberra

[6]. Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Migration Australia 2016-17, cat no. 3412.0, Net Overseas Migration

[7].

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS),2016

Census of Population and Housing, Cultural diversity in Australia, 2016 Census article

[8]. Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Population projections, 2017 (base) – 2066, cat not 3222.0

[9]. Ibid

[10].

Australian Bureau of Statistics

(ABS), Australia's population to reach 30 million in 11 to 15

years, media release, 22 November 2018

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.