14

July 2017

PDF version [367KB]

Nigel Brew

Foreign Affairs, Defence and

Security Section

Every few

years since the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, a proposal to establish

some sort of Australian homeland security department has been put forward as

part of the national security policy of either the Liberal/National Coalition

or the Australian Labor Party (ALP). Citing the US Department of Homeland Security and the UK Home Office

as inspiration, its general purpose has always been to coordinate all the

federal national security functions of government. However, rarely do the two

major parties agree on the need for such a significant change, and as recent

speculation over a possible new proposal shows, 2017 is no different.

The proposal for an Australian

department of homeland security seems to have originated in late 2001 as ALP

policy under Kim Beazley while in Opposition. It persisted as ALP policy until

2008 when Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, acting on the advice of a review of security

arrangements, abandoned the idea altogether. The concept was resurrected in mid-2014

by the Abbott Coalition Government, until Prime Minister Tony Abbott also

formally abandoned the idea less than a year later, acting on the advice of a

review of Australia’s counter-terrorism machinery. Reports that the concept is

once again under consideration, this time by the current Turnbull Government,

appear to have surfaced in January 2017. This quick guide summarises the

history of the concept since 2001.

Labor election policy (Kim Beazley, 2001 federal

election)

In the election campaign for the November 2001 federal

election, the Labor Opposition (under Kim Beazley) announced

a policy to formally adopt the concept of ‘homeland security’ and establish a

portfolio of home affairs:

Enhancing Homeland

Security

Labor will formally adopt the

concept of "homeland security". This means that in addition to

protecting our sea, air, immigration and electronic borders through the

measures described above, we will improve our ability to protect important

physical assets and installations within our borders. This includes buildings,

power and water supplies, transportation and communications systems and other

national assets. The Minister for Home Affairs will be responsible for homeland

security in relation to the protection of vital assets and installations. Labor

will establish a Federal Protection Service as the frontline agency to

undertake these tasks (see below).

The Home Affairs portfolio

will also be responsible for the related task of national emergency disaster

response and civil defence. In addition to civil authorities, the Commonwealth

will be able to call upon the ADF where necessary to assist in the task of

homeland security through the legal procedures and protections developed last

year through Labor's amendments to the "aid to the civil power"

legislation.

...

Creating a Home Affairs

Portfolio

Labor will appoint a Minister

for Home Affairs in the Cabinet and establish a portfolio of Home Affairs. This

portfolio will be responsible for a range of non-security administrative

functions of state (including the public service and ministerial and parliamentary

services) and all Commonwealth security functions outside of Defence, in the

following areas:

- Law enforcement (including the AFP

and the National Crime Authority);

- Counter-terrorism (in conjunction

with the Minister for Defence);

- Coastal surveillance (including the

Coast Guard);

- Aviation security;

- Security intelligence (including

ASIO);

- Homeland security (including the

Federal Protection Service);

- Telecommunications interception;

- Protection of National Information

Infrastructure;

- Customs; and

- National emergency response and

management.

The Home Affairs ministry will

provide a powerful and coordinated focal point for strengthening Australia's

national security and fighting global terrorism. It will guarantee enhanced

coordination between Commonwealth law enforcement, intelligence and security

agencies, and between civil authorities and the Defence Organisation.

The Home Affairs ministry will

be the most powerful and focussed peacetime ministerial arrangement for

co-ordinating Australia's domestic security in our history. Its time has come

and the times demand it.

Labor Opposition (Simon Crean, 2002)

In March 2002, the Opposition spokesman for the new shadow

portfolio of Public Administration and Home Affairs, John Faulkner, reiterated

Labor’s plan to create a ‘Cabinet level minister for home

affairs’:

A home affairs ministry would

be a powerful and focused peacetime arrangement for coordinating Australia's

domestic security— a first in Australia's history. We are still committed to

such a plan and that is why Simon Crean has chosen to create the new shadow

portfolio of public administration and home affairs. This shadow portfolio has

coverage not only of Commonwealth security functions but also of nonsecurity

and administrative functions, including the Public Service and ministerial and

parliamentary services. It seeks to achieve better coordination between law

enforcement, intelligence and security agencies as well as civil authorities

and the Defence organisation. Areas of responsibility include ASIO, aviation

security, information infrastructure protection, international cooperation on

terrorism, national security and counter-terrorism, protective security policy

and coordination. Accordingly, the shadow home affairs portfolio will cover

agencies such as the Australian Federal Police, Australian Security

Intelligence Organisation, Australian Protective Service and Protective

Security Coordination Centre. Further, this portfolio will be handling the

package of security laws currently before the federal parliament.

The opposition believes the

creation of a cabinet level home affairs ministry would provide a more

efficient and effective way to coordinate and integrate the various Australian

government activities involved in securing our nation, particularly in the

light of the escalation of international terrorism manifested by the September

11 attacks on the United States. Labor believes that, after the events of

September 11, greater efforts must be made to ensure that Australia is as

effective as possible in the coordination of its homeland security. The entire

notion of threat to national security has been transformed as a result of the

terrorist attacks on that day and we must rethink the way we look at national

security issues.

Since September 11, the United

States has taken a fresh look at its homeland security. Tragically, what was

evident from the September 11 attack was a lack of communication and

coordination between the different security departments. The Bush

administration acted quickly to rectify this situation by establishing the

Office for Homeland Security. This office aims to develop and coordinate a

comprehensive national strategy to strengthen protections against terrorist

threats or attacks in the United States by coordinating federal, state and

local counterterrorism efforts. The office headed by Tom Ridge, former governor

of Pennsylvania, is a cabinet position, directly reporting to President Bush on

homeland security matters.

Howard Government (May 2003)

In May 2003, it was reported

by the media that Prime Minister Howard would ‘set up a new office of security

and counter-terrorism to co-ordinate his Government’s actions on homeland

security’. This unit was said to have ‘the main responsibility for national

security, counter-terrorism and border protection’, and would be located within

the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. It was claimed the decision

followed ‘bureaucratic concerns that responsibilities for counter-terrorism and

security had been spread across too many departments, leading to overlaps and

fragmentation’.

Mr Howard was quoted at

the time in another report denying it was an attempt to establish a homeland

security department under another name:

It is in no way a de facto

homeland security department. We don't need a homeland security department. It

will certainly further bolster the coordination arrangements and provide even

better streams of advice to me.

This same report quoted Labor’s ‘Homeland Affairs

spokesman’, Senator Faulkner, indicating his support for the move and Labor’s

continued support for a department of home affairs:

JOHN FAULKNER: What Mr Howard

has said consistently is that there's no, there's no advantage to changing

bureaucratic structures in Australia. That was his response when the Labor

Party said a couple of years ago, we should have a home affairs department.

Prime Minister said well look there's no need for changing bureaucracies here

we've got to get on with the job.

Now, reluctantly, we have a change in relation to the bureaucracy. It's

actually happening in the Prime Minister's own department. It's a step in the

right direction, but it doesn't go far enough.

We need to establish in Australia, a department of home affairs. We need to do

what is now the accepted situation in both Britain and the United States of

America.

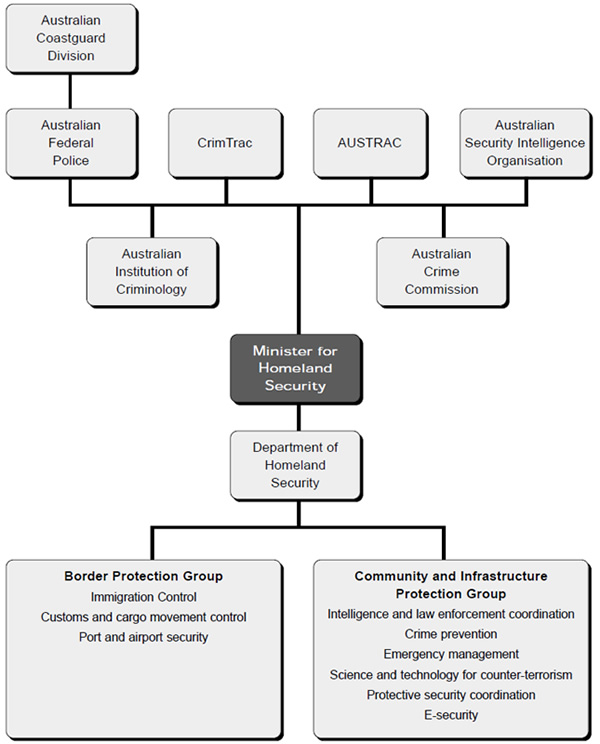

Labor Opposition (Mark Latham, December 2003)

On 8 December 2003, following the ALP leadership ballot

precipitated by Simon Crean’s resignation as Opposition Leader, in which Mark

Latham defeated Kim Beazley to become the new leader, Mr Latham announced

his new ministry. This was notable for the creation of a new Homeland Security

portfolio:

I have appointed Robert

McClelland to the newly created Homeland Security portfolio, demonstrating

Labor’s commitment to a dedicated Cabinet Minister responsible for security in

Australia. The portfolio will encompass border protection, crime prevention,

intelligence-gathering, investigation and prosecution, taking in all domestic

counter-terrorism agencies – as well as Labor’s community security agenda.

It will provide a one-stop

shop approach for working with the States and Territories to enhance

Australia’s national security. We must win the war against terror

internationally, plus secure the home front against the threat of terrorism.

Labor’s Department of Homeland Security is a fully integrated and coordinated

way of achieving this vital goal.

The Minister for Justice at the time, Chris Ellison, was reported

to have attacked the idea:

But Justice Minister Chris

Ellison says the current arrangements are working well and Labor's plan would

be expensive and wasteful.

"That's patchwork at

best," he said.

"It's a cynical

window-dressing exercise which is going to bog down Australia's anti-terror

efforts in bureaucratic quicksand.

Labor election policy (Mark Latham, 2004 federal

election)

In the lead-up to the October 2004 election, the Labor

Opposition (under Mark Latham) pursued its department of homeland security

proposal, offering

a proposed structure in August 2004:

Labor election policy documents released

in October 2004 again summarised the ALP’s plans:

Labor’s priority will always

be security on the home front and security in the region. That is why Labor has

proposed the establishment of the Department of Homeland Security. That is also

why Labor has proposed the establishment of an Australian Coastguard. And that

is why Labor now argues in this policy statement that Australia must now

develop a properly integrated regional response to the terrorist threat.

Among a raft of detailed criticisms of Labor’s plan in the

Howard Government’s election

policy on national security, there was this summary (p. 46):

In the absence of an original

and coherent policy framework of their own, the ALP has ironically adopted from

the United States their two national security proposals.

The first is the establishment

of a department of homeland security and the second the creation of a US style

coastguard.

Both of these proposals are

ill suited to Australia’s national security needs and if implemented will be

counterproductive, leaving Australians less secure.

Both the Coastguard and a

Department of Homeland Security would represent an expensive exercise in

bureaucratic reshuffling which will undermine the effective and proven systems

already in place.

Labor election policy (Kevin Rudd, 2007 federal

election)

In the election campaign for the November 2007 federal

election, the Labor Opposition (under Kevin Rudd) again pursued its proposal

for a department of homeland security. The Shadow Minister for Homeland

Security, Arch Bevis, outlined Labor’s plans in some detail in a speech

on 3 October 2007, in which he also detailed Labor’s plans to produce a counter-terrorism

white paper by the end of 2008 should it win government (pp. 5–6):

The first step in ensuring a

clear focus on these issues and a genuine whole of government response is the

creation of a Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

Maintaining the integrity of

maritime and national borders, as well as protecting Australians at home is an

increasingly demanding responsibility of national government.

New threats have emerged that

demand a rethink of our nation’s strategic and tactical response.

The Federal Government saw the

importance of combining critical security agencies under one command in the

lead up to the Sydney Olympics, yet it has avoided the difficult decisions in

restructuring its own departments to provide a similar single structure for homeland

security.

The Howard Government’s

continuing insistence on splitting these functions over a number of departments

invites overlap, wastage, confusion and missed opportunities.

The logic of those who argue

that civilian security should be administered in separate departments

responsible to various ministers is reminiscent of those who argued forty years

ago, that Australia should maintain separate Ministers for Army, Navy, Air

Force and Supply. No one today would disagree with the decision in the early 1970’s

to create a Defence Department with a single Minister for Defence. The same

clear sighted vision for non military security agencies is required today.

...

Interdepartmental committees

are not a substitute for a single minister with clear responsibility for a

Department of Homeland Security providing a whole of government response to

these challenges.

Labor’s Department of Homeland

Security will encompass the key responsibilities of responding to terrorism,

intelligence gathering, border security, a national coastguard, transport

security, federal policing, critical infrastructure protection, as well as

incident response and recovery capability.

The following agencies would

form the basis of Labor’s Department of Homeland Security:

- The Coastguard – including the

Border Protection Command

- Office of Transport Security

- Customs

- Australian Federal Police and

Protective Services (AFPPS)

- Australian Security Intelligence

Organisation (ASIO)

- AUSTRAC

-

CRIMTRAC

- AUSCHECK

- Australian Crime Commission (ACC)

- The Australian Institute of

Criminology (AIC)

- The Criminology Research Council

(CRC)

- Emergency Management Australia

(EMA)

- Protective Security Coordination

Centre (PSCC)

Once again, Labor’s plan drew criticism from the Howard

Government, including this comment

from the Attorney-General, Philip Ruddock:

“A Department of Homeland

Security would not enhance current security arrangements. It would be expensive

and it would create bureaucratic upheaval that could undermine well-tested

arrangements.”

“Kevin Rudd likes to paint the

Coalition as slavishly following the US. Yet it is Labor who is all the way

with the USA with its idea to simply copy the US-style Department of Homeland

Security even though Australia does not have the same problems faced by the US ...”

Rudd Government (2008)

Following its election win, in late February 2008 the newly

elected Rudd Government commissioned

Ric Smith (a

former Secretary of the Department of Defence and former

Ambassador to China and Indonesia) to conduct a review of homeland and

border security. The purpose of the Review was to ‘consider the roles,

responsibilities and functions of departments and agencies involved in homeland

and border security’ and to ‘also consider possible changes to optimise the

coordination and effectiveness of our homeland and border security efforts’.

The public version of the Review’s report was released on 4 December

2008 to coincide with Australia’s inaugural

National Security Statement, delivered in Parliament by Prime Minister Rudd

the same day. Among a number of recommendations, the Review recommended against

creating a department of homeland security, although it did not use these

words, referring only to one option being to ‘create new organisations or merge

existing ones’, as other countries had done:

This approach raises several

risks. It could disrupt unduly the successful and effective work of the

agencies concerned and create significant new costs. Large organisations tend

to be inward-looking, siloed and slow to adapt, and thus ill-suited to the

dynamic security environment.

The Review instead considered it ‘more appropriate for

Australia’ to deal with the changing security environment by ‘recognis[ing] and

build[ing] on the strengths of existing institutions but to identify weaknesses

and address them’. This, the Review said, would ‘recognise that our existing

arrangements are generally effective and that for the most part our departments

and agencies are working well with each other’. The Review also added, ‘above

all, the smaller, separate agencies which comprise this model are likely to be more

agile and accountable than large agencies’. For this model to work, however,

the Review suggested two things were required—(i) both agencies/departments

with dedicated security functions and those contributing to national security

needed to be regarded as a community, and (ii) that ‘the departments and

agencies concerned must be well connected and networked, and cultural,

technical and other barriers minimised’.

According

to the Prime Minister, the Government ‘strongly agreed’ with the Review’s

recommendations, including the advice against creating a department of homeland

security:

The government in

opposition made a number of commitments on national security upon coming to

office. Perhaps the most hotly debated was the proposal to create a department

of homeland security. The Smith review considered the option of achieving

greater cooperation by creating a department of homeland security, and did not

recommend that model for Australia. The government has accepted this strong

advice. Mr Smith’s advice is that big departments risk becoming less

accountable, less agile, less adaptable and more inward-looking. What we need is

the opposite.

It seems that from this point on, Labor’s long-held ambition

to create a department of homeland security ceased to be ALP policy.

In response to Prime Minister Rudd’s National Security

Statement, Malcolm Turnbull, then Opposition Leader, commented

in Parliament on Labor’s decision to abandon its proposal for a homeland

security department:

... we note that the Labor

Party has abandoned its election pledge to create a department of homeland

security. This is one broken promise for which we can all be very thankful. It

was a very poorly conceived idea—a cheap copy of an American experiment. It was

crafted more to capture campaign headlines than as a serious public policy

reform.

...

So that was to be the template

for a Rudd revolution to overhaul in its entirety our national security

establishment. According to Labor’s critique, the coalition had been putting

Australians in harm’s way by allowing each of our security agencies to operate

within its own area of specialisation. Labor’s answer was to bring it all into

one gigantic superbureaucracy, and today the Prime Minister himself has exposed

that proposition as the hoax it always was. The truth of it is that what Labor

was proposing was a wasteful and costly exercise in bureaucracy. It would have

meant reinventing well-established patterns of cooperation and coordination

between our key security agencies and confusing and complicating the existing

practice of reporting lines within and between those agencies.

So it is welcome that the

Prime Minister is prepared to jettison one of the key planks—possibly the key

plank —of the national security policy he took to the last election. For this

we can thank the sound, determined and intelligent advice of our professionals

in the field. The Prime Minister was strongly advised as far back as July, in

the report by the former Secretary of the Department of Defence Mr Ric Smith, that

he should not go ahead with his plans for this Rudd security revolution. It

took the Prime Minister a long time to swallow this particular medicine, but

the fact that he has now agreed to the unceremonious dumping of this

centrepiece of Labor’s national security policy is a victory for common sense.

Abbott Government (2014)

In September 2014, speculation arose in the media

that ‘any reshuffle by Abbott could see [Immigration Minister

Scott] Morrison put in charge of a ramped-up homeland security-type portfolio’.

At least part of the source of the speculation appears to have been a joint announcement by Prime Minister Abbott

and the Attorney-General in early August 2014 that the Government would conduct

a ‘review of Australia’s counter-terrorism coordinating machinery’,

which included the statement:

Australia is well served by

the agencies involved in counter-terrorism, but the review will ensure that

they are as well organised, targeted and effective as possible to meet current

and emerging threats, drawing where appropriate on international best practice.

It was soon being widely reported

in the media

that Scott Morrison, then Immigration Minister, was believed to be pushing

within the Government for the creation of a homeland security department,

possibly overseen by him. This was reportedly

not supported by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) or the Australian Security

Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), nor many of his colleagues.

Notable among government figures who publicly questioned the

idea was the Foreign Minister, Julie Bishop, and the Attorney-General, George

Brandis. Ms Bishop was quoted

saying:

“If there were such a

proposal, it would have to demonstrate any current failures in co-operation

between the intelligence agencies, federal and state police and Defence and I

am not aware of any such failures”.

Similarly, Senator Brandis stated

in response to a question at the National Press Club:

I think it is good governance

to always keep our institutions and our institutional architecture under review

to make sure that they are as fit for purpose and effective as they can

possibly be. And I was one of the national security ministers who made the

decision to have a review about two months ago. That being said, I agree with

my colleague Julie Bishop, who was reported yesterday as saying that if the

institutional arrangements were to be changed then obviously those who would

seek to change them would need to persuade, to demonstrate that they're not

working.

In late October 2014 the Prime Minister seems to have attempted

to defuse the ongoing speculation by stating

in a radio interview that ‘national security is fundamentally my

responsibility’. However, speculation persisted into November when it began

being reported

that the Government was actively considering the creation of a department of

homeland security, with a particular model favoured by the Prime Minister.

However, Mr Morrison would not comment,

referring instead to the Review underway and the fact that it was the Prime

Minister’s decision.

The Review

of Australia’s Counter-Terrorism Machinery was released in late

February 2015. While the Review concluded that there is ‘no single

international best practice model on which to base Australia’s CT governance

arrangements’ (p. 23), it also stated that it agreed ‘with the conclusion

reached by the Smith Review that a small, coordinating Department of Home

Affairs could be effective at leading Australia’s CT effort if the department

focussed on strategic issues’ (pp. 23–24). However, it also acknowledged

‘practical challenges’ to establishing a department of home affairs and

concluded, much like the Smith Review, that ‘in respect of CT, this Review

therefore concludes there is no compelling reason to change the current system

of ministerial oversight and departmental structures. Rather, it should be

retained and strengthened’ (p. 26).

Accordingly, while Prime Minister Abbott committed the

Government to implementing many of the Review’s recommendations, he acknowledged

that ‘the Review confirmed that Australia has strong, well-coordinated

counter-terrorism arrangements and there is no reason to make major structural

changes’.

Turnbull Government (2016–2017)

On 7 November 2016, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced

an Independent Intelligence Review—‘an independent review into Australia’s

intelligence agencies’ for the purpose of assessing ‘whether our current

intelligence arrangements, structures and mechanisms are best placed to meet

the security challenges we are likely to face in the years ahead’. The terms

of reference are available on the website of the Department of the Prime

Minister and Cabinet.

Former senior public servants, Professor Michael L’Estrange and Stephen

Merchant, were appointed to conduct the Review, which was expected to report to

the Government in the first half of 2017. Among other positions, Professor

L’Estrange served as Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

and as Australia’s High Commissioner to the UK, and Mr Merchant was once

Director of the then Defence Signals Directorate. They were assisted by Sir

Iain Lobban, former Director of the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters

(GCHQ).

In mid-January 2017, media

reports began to claim that Cabinet had discussed the possibility of

creating a homeland security ministry and was reportedly favouring a model

similar to the UK’s Home Office. It was claimed that a group of MPs had been

urging the Prime Minister to consider such a change. On 7 March, more detailed

claims appeared in the media, including

that ‘the proposed new department would be based on the existing Department of

Immigration and Border Protection’ to which the AFP, ASIO, the Australian

Criminal Intelligence Commission and the Australian Transaction Reports and

Analysis Centre (better known as AUSTRAC) would then be added. When it was put

to the Prime Minister at a doorstop

press conference the same day that reports were claiming the Government had

established a ‘US-style homeland security department’, he refused to comment on

what he called ‘speculation about administrative arrangements’.

Similarly, despite some reports claiming

that the Immigration Minister, Peter Dutton, was promoting the idea, Mr Dutton said

in a radio interview at the time that he was unaware of ‘the process’ and that

if such a proposal was being considered, it was ‘an issue for others’. In a

separate interview

in mid-March, the Attorney-General, Senator Brandis, said it was a matter for

the Prime Minister and that we should wait for the Independent Intelligence

Review to be completed. In subsequent interviews,

Mr Dutton also deferred to the Prime Minister and emphasised that machinery of

government changes are only ever made if they are going to improve the system.

In mid-June 2017, a media

report claimed that ‘a super agency in the style of the US Department of

Homeland Security is understood to have been all but ruled out, but the British

model is being considered more seriously’, and that the Prime Minister was

understood to be ‘leaning towards the British-style approach with Immigration

Minister Peter Dutton to head the new portfolio’. The report also claimed that

the Independent Intelligence Review is ‘not tipped to make any concrete

recommendation on whether to set up a Home Office’ and suggested that any

portfolio reshuffle would most likely occur in December 2017.

At a joint

press conference in London on 10 July 2017 with the British Prime Minister,

Theresa May, Prime Minister Turnbull was asked to comment on speculation that

the Australian Government was considering adopting a ‘British-style Home

Office’. He would only say in response that Australia is ‘always interested in

learning about the British experience’ and that ‘we will always seek to improve

our national security arrangements to keep Australians safe’. Echoing comments

he made in the Australian Parliament on 13 June 2017, the Prime Minister

emphasised at the press conference that ‘as far as administrative arrangements

in Australia with respect to national security ... this is no place for

set-and-forget’.

On 14 July 2017, the Attorney-General confirmed in an interview

that ‘a discussion’ about the possibility of restructuring current security

arrangements was ‘going on inside Government at the moment’.

In amongst all the speculation, there has been little

explanation of the distinction being made between a model based on the US

Department of Homeland Security and one based on the UK Home Office.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.