Papers on Parliament No. 41

December 2003

Prev | Contents | Next

For some 25 years my professional life revolved around the Commonwealth Government. This period covered my time as a public servant with the Commonwealth Treasury, my time as a ministerial staffer with Paul Keating and my time in Washington as Australia’s ambassador to the United States.

In this I was privileged to have worked, or been in close contact with, a wide range of officials and politicians who held high office in both Australia and the United States. My time with Paul Keating was one of those rare opportunities to work with a remarkable political figure who has left an unrivalled legacy of achievement. The Keating years helped build the modern Australia. They also provided me with great insights into how governments and nations work.

I feel privileged for my time in the United States. It brought me into close contact with senior members of all branches of the US government, and gave me an appreciation of why Australia’s founders deliberately chose to incorporate into our system a number of US-type institutions.

I have now been away from the Commonwealth Government for six years, which has allowed me to survey all of this, hopefully, with some perspective. My overriding impression is that our system of government is still evolving and that the power of the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office continues to rise. At the same time, we have seen a trend of decline in the power and influence of the Public Service. The question is: does our system have the right balances? This paper explores these issues and makes some suggestions as to what might be done.

First, I will look at the logic behind US arrangements to better understand what it is we have incorporated into our system. Then I will look at the United Kingdom. Our system draws very heavily on British processes—why they provide a powerful discipline on government in the UK but have proved weaker here is an important part of the story.

The US approach

In the US, government is based very much on the notion that without explicit ‘checks and balances’ people or groups of people will abuse positions of power. This is the origin of the separation of powers and the creation of a judiciary, a legislature and an executive as three separate branches of government. It is also why the US incorporated into its Constitution a Bill of Rights, which constrains how US governments at both a state and federal level can deal with their citizens.

At the time, the Constitution was deemed to provide for a government in Washington with considerable powers, and the Bill of Rights was very much the quid pro quo that was required to get the Constitution approved. The Bill of Rights was designed to protect Americans from a powerful government in Washington rather than to codify the rights of citizens.

The concern that elected officials will abuse their power is very real to Americans as is the fear that the ‘tyranny of the majority’ may lead to unfortunate outcomes for minorities or individuals. Americans are uncomfortable with ‘winner takes all’ politics and their system of government has been elaborately designed to diminish this possibility. To Americans, democracy does not mean an elected George III, to return to the debates of 1776. You will often hear this said by Americans and it means that electing someone with absolute power is not democracy even if the mandate of such a person is regularly renewed.

For a long time, the Americans believed that they could operate with a congressional form of government; that is, one without a President. Lying behind all of this is the conviction that elected officials are not necessarily well motivated. Indeed, if individuals or groups secure power it is assumed that this power will be used to further the interests of those involved. The only way that good outcomes can eventuate is if no one has unfettered power and if those with power have to exercise it in a transparent, contestable and accountable way.

For example, Americans would assume that without scrutiny, government contracts would go to supporters of the government and that policy decisions would be skewed towards those who put the government there in the first place. Americans assume instinctively that politics is about plunder. Why put an elected official in place unless he or she is working for you at the expense of others? They would also assume that elected officials would use every influence that comes from their office to secure their position and weaken that of their opponents even if this comes at the expense of good government.

It should come as no surprise to Americans to be told that the US Congress was slower than the Australian Parliament to recognize the need for disclosure laws for politicians. Americans believe that only an elaborate system of ‘checks and balances’ will ensure that elected officials are mindful of their responsibilities to the broader community and that the power of government is used for worthy purposes.

Americans, however, are very wedded to the status and standing of the Office of President. As head of state, the President represents the nation and its ideals and Americans are very supportive of any President whenever he is performing this role.

To many outsiders, the American system appears dysfunctional. It seems to put major roadblocks in the way of anyone attempting to put a new policy in place or to even modify an existing one. The ‘checks and balances’ appear to be a recipe for gridlock. On the other hand, Americans will assure you that their system works exactly as designed. It is accepted that there are hurdles, but these exist to inhibit sectional interests profiting at the expense of the wider community. If significant change is to occur, it needs something close to a consensus. As the Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Patrick Moynihan, argued from the start during President Clinton’s ill-fated attempt to reform health care: big social programs like universal health insurance either achieve a consensus and pass the Senate with large majorities, or they do not pass at all.

Outsiders would see the impeachment of President Clinton as an extraordinary aberration, highlighting the weaknesses of the American system of government. Americans tend to see it as a validation of their system of ‘checks and balances’ and further evidence of the strength of their Constitution and the wisdom of the founding fathers. The popular house impeached the President and the more balanced house exonerated him. The debate was conducted publicly and the President was given time to build popular support. In the end, the President’s party fared well in the mid term elections of 1998, the Speaker of the House, Newt Gingrich, was forced to resign and a consensus built that the Independent Counsel Act should be allowed to lapse. This brought to an end an experiment in executive oversight that had its origins in a perceived need to deal with the excesses of the Nixon White House.

To Americans their democracy may be noisy and inefficient but it has a built in capacity to self-correct. Self-correction may take decades but the system will remain grounded on what people really want. In the long run, the practical workings of even the Bill of Rights only guarantee those freedoms that the majority will support.

Americans would also say that because they are a violent, immigrant county with a wide diversity of cultures, the US would have fractured long ago if they had tried to run their country with a ‘winner takes all’ system of government. Abstracting from the issue of slavery, memories of the civil war still exist but they are remarkably muted given that some 500 000 Americans died and that it happened little more than four generations ago.

The American capacity to accommodate a diverse range of ethnic and cultural backgrounds stands in marked contrast to what is happening in much of the rest of the world. Elsewhere, we see countries being redefined on a narrowing set of ethnic characteristics. Ancient events continue to drive emotions and behaviour. In the US, it took just over 100 years, but the South did eventually vote for the party of Lincoln.

One can believe that the future lies with those countries or regions that can manage cultural and ethnic diversity. For from diversity comes energy and, most importantly, critical mass. If there is a lesson from the US, it is that diversity requires a political structure that decentralises power or sets up a system of ‘checks and balances’.

In concept, an ‘elected George III’ or a ‘winner takes all’ system of government may bring a semblance of efficiency but it also brings a rigidity that makes such systems unresponsive to changing circumstances and ill suited to deal with diverse interests.

The UK approach

On the face of it, a British Prime Minister would appear to have powers akin to an elected George III. He or she controls the Cabinet and the House of Commons, and the House of Lords is no longer a major constraint. In Britain there is no written constitution and no formal equivalent to the Supreme Court.

However, a British PM is constrained by an elaborate and well-entrenched system of convention and by a Cabinet backed by a powerful and effective civil service. The UK is the home of the unwritten Constitution and while it may appear to be a self imposed discipline it would be unheard of for any British government to flout its provisions. Convention keeps British governments grounded on due process and ensures that the Cabinet and the Civil Service are actively involved. Ministers and the Prime Minister are also held to account at Question Time where lying and general incompetence are ruthlessly punished.

To the British, good government does not necessarily mean great public scrutiny but it does mean that decisions should be taken once issues have been properly assessed and the advocates of the various alternatives have had their say. The clearinghouse of this process is the Cabinet. A well-briefed Cabinet with a number of influential members is a powerful check on any individual minister or even a Prime Minister.

The British Civil Service sees itself as serving the government of the day but collectively it also sees itself as the guardian of the public interest. Over the years, the British have worked to secure a reasonable balance between the need for ministers and departments to operate in an atmosphere of trust and the need to protect good government. This has required a measure of common sense and diplomacy. A tradition has therefore built up to resist ill-conceived policy and anything that undermines due process and good government.

Americans are baffled as to why the British system works.

The Australian approach

Right from the start, Australia opted for something of a hybrid.

Our system of government involves a number of explicit ‘checks and balances’ that are missing from the UK model. We have a written Constitution, a High Court and a Senate with powers similar to those of the lower house, and a franchise designed to protect the interests of the smaller states. The provisions of the Constitution also provide for a Governor-General to act as a check on the power of any Australian government and in the early years these provisions of the Constitution were viewed as having real meaning.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Australia was a much more homogeneous country than the US and on a per capita basis almost certainly richer. For the times, class antagonisms were muted. Ordinary people had incomes and living standards higher than anywhere else in the world. Governments were socially progressive and worker based parties had already organised their way into government. Like the US, Australia was an immigrant country but immigration at that stage was overwhelmingly from the UK, unlike the US, where immigrants were arriving from all over Europe.

We had the ugly history associated with the dispossession of our aboriginal population, the transportation of the convicts, the presence of the Irish and a degree of frontier lawlessness. However, we had nothing of the history of violence experienced by the Americans and nothing in Australia’s history matched the dislocation associated with the War of Independence and the Civil War.

However in becoming a nation we did have to accommodate one source of diversity. We were willing to become one country, but many people were loyal to the state in which they lived. More importantly, there already existed power structures at a state level and a class of professional state politicians.

We looked, therefore, to the US to build into our system of national government explicit ‘checks and balances’ to protect against ‘winner takes all’ politics at a national level. The result was a federal system, a written constitution with limited federal powers, and a High Court and a Senate modeled very much on their US counterparts. The new federal arrangements accommodated the interests of the states so effectively that until World War Two, the Premier of New South Wales continued to be regarded as the most important political figure in Australia.

Our Constitution also provides for a Governor-General to take an active role in the operations of the Australian government, a role most clearly set out in Section 58 and Section 62:

58. When a proposed law passed by both Houses of the Parliament is presented to the Governor-General for the Queen’s assent, he shall declare, according to his discretion, but subject to this Constitution, that he assents in the Queen’s name, or that he withholds assent, or that he reserves the law for the Queen’s pleasure.

The Governor-General may return to the House in which it originated any proposed law so presented to him, and may transmit therewith any amendments which he may recommend, and the Houses may deal with the recommendation. …

62. There shall be a Federal Executive Council to advise the Governor-General in the government of the Commonwealth, and the members of the Council shall be chosen and summoned by the Governor-General and sworn as Executive Councillors, and shall hold office during his pleasure.

At the time, Section 58 in particular made the Australian Governor-General a much more influential figure than the British monarch. It was assumed that the Governor-General would be a distinguished Englishman and on one level, Section 58 can be seen as a device to ensure that the new Australian Parliament did not pass laws harmful to British interests. However, given British attitudes of the time, there was doubtless a view that good government in the new nation could only benefit from the steadying hand of someone of worldly experience sitting one removed from the Parliament with a power to intervene. The ‘White Australia Policy’ and the power of the new Parliament to make laws in respect of race would have also been a concern of the British at the time.

The British are no longer involved in the operation of government in Australia and the Governor-General is now seen as having quite limited powers. However, the black print oversight provisions of the Constitution providing for an activist Governor-General still remain.

While we have incorporated important institutional structures from the Americans, the dominant influence has been British. We have Ministers of State drawn from the Parliament firmly tying the executive to the legislature. And like the UK, we also developed a powerful Public Service. This was particularly the case after the Second World War. Government in Australia has also been bound by convention, although the role of convention has always been an ambiguous one in Australia and much weaker than in the UK.

Because of the power and standing of the Public Service, Australia built up an effective system of government based around due process and the Cabinet. It was at its most effective during World War Two and in the post-war years. These were the good years for Australia, when commodity prices were high and when much of the world was still recovering from the destruction of the war, or preoccupied with the Cold War. This was the time of the ‘seven dwarves’, as the key departmental Secretaries of the time were known, and the rapid expansion of Canberra and federal influence.

During this period Australia once again embarked on a large immigration program which brought a growing number of people of differing racial and cultural backgrounds to our country. Within a generation, Australia had abandoned its ‘White Australia Policy’ and dramatically changed the size and composition of its population. The country has therefore become very much larger, more diverse and more complex. That this was done with relative calm is a credit to our institutions and our political structures. But this period is now well and truly over, and the intriguing question is how our system of government has coped with the more turbulent years that date from the oil price shocks in the 1970s and our growing diversity and complexity.

The decline of the Public Service

I started work at the Commonwealth Treasury at the end of 1971 as a junior economist fresh out of university. Fred Wheeler was just starting his career at the Treasury, McMahon was Prime Minister, and it was the dying years of the Coalition Government. John Gorton had just lost his job as Prime Minister, in part due to a perceived tendency to ‘shoot from the hip’ and ignore due process.

At the time, I was struck by the dignity of the Treasury and the power it wielded. I was also struck by the supreme confidence that high Treasury officials had about their role.

One of my earliest jobs was to read the morning newspapers and draw important stories to the attention of Bill Cole. Bill Cole, at the time, was responsible for macroeconomic policy and headed up the General Financial & Economic Policy Division, which in those days covered budget policy, monetary policy, structural policy and taxation policy. I quite enjoyed my morning task as I got to talk to Cole about the issues of the day. I remember drawing his attention to newspaper articles dealing with the growing concerns about foreign investment. I was somewhat surprised by the sympathy that Bill Cole expressed to the articles, but more intrigued by his pensive remark that, ‘Yes, they needed to do something about foreign investment.’

A number of weeks later, the McMahon Government announced that they would be introducing legislation to monitor and review foreign takeovers of Australian companies to ensure that they were in the best interests of Australia. This was a little surprising as it had been McMahon as Treasurer who had argued against the more nationalist tendencies of John Gorton.

So was born the Companies (Foreign Takeovers) Act 1972. It led to a new Division of Treasury, the Foreign Investment Review Board, the extracting of rent from foreign mining companies, the scrutiny of all foreign acquisitions and new businesses above a certain size, controls on real estate, and structure to the special controls on foreign ownership of media, airlines and banks. I surmised that what had changed had been Treasury advice. Knowing the people, it seemed unlikely that such a major shift in policy could have occurred over the strong objections of the department. Presumably Fred Wheeler, with his commitment to ‘proper processes’, preferred to have foreign investment handled in a structured way within Treasury than left to the mercy of others. I could not have asked for a clearer example of how, at that time, the national policy agenda, as well as the implementation of policy, was very much in the hands of senior Canberra public servants rather than ministers and their staff.

However, change was afoot. It was not just John Gorton who was irritated by the controlling influence of the Public Service and the Treasury in particular. Gough Whitlam, elected at the end of 1972, was determined to implement his own agenda and for the first time ministers were provided with staff whose prime responsibility was to provide policy advice and to help ministers develop and implement policy.

The important ministerial staff were in the Prime Minister’s Office, the most famous being Peter Wilenski and Jim Spigelman. Professor Fred Gruen was also a consultant to the Whitlam Government. Fred Gruen was a family friend and we used to have sandwiches in the park out the front of the Treasury, which perplexed my Treasury colleagues.

Fred Wheeler served the new government loyally within parameters he believed best served the public interest. He endeavoured to protect his minister and struggled to achieve sensible outcomes during a very chaotic period, when Cabinet processes were erratic and the Treasury was treated with suspicion and largely ignored. The economic statistics for 1974–75 tell the story: public sector outlays grew by 37 per cent as a result of the 1974 Cairns Budget; average weekly earnings grew by 25 per cent, while the Consumer Price Index rose by 17 per cent. The dislocation to the Budget and the economy was immense.

Fred Wheeler is perhaps best known for his remarks at his farewell speech in 1978 where, among other things, he has become known for saying that ‘all politicians are bastards.’ At the time, I thought that this comment was unfair. As I have come to know better since, Fred Wheeler’s comment did not do justice to the many politicians who at great personal cost give a lifetime of service for very little recognition. However, Fred Wheeler’s comment did reflect the ethos of the high period of Public Service life in Canberra.

I never had the conversation with Fred Wheeler but I have always assumed that he would have said that politicians can act nobly but only after they have exhausted all available alternatives. Fred would have seen his role as enabling politicians to behave well. He assumed that politicians would push until they find limits. Without limits, I am sure he believed, politicians will behave badly and in the end damage themselves as well as the country. To Fred Wheeler it was the role of the Public Service to short-circuit this process and find acceptable ways to create limits that would be in the best interests of the politician and the country.

Bill Hayden became Treasurer before the 1975 Budget. Fred Wheeler, consummate stage manager of anything involving the minister, included me in one of the early discussions on budget policy. I was a relatively junior official in the monetary policy section at the time but I was about to go to the London School of Economics to do post graduate study and Fred Wheeler thought I might be helpful with the new Treasurer.

Bill Hayden appeared to immediately appreciate that involving the Treasury would not only help stabilise the Whitlam Government but would also make it easier to achieve the government’s policy goals. Unlike his immediate predecessors, Bill Hayden saw the Treasury as an important resource to use. The next Labor Treasurer, Paul Keating, came to the same conclusion but even more so.

After the defeat of the Whitlam Government at the end of 1975, things did not go back to the pre-Whitlam processes. On the contrary, ministerial staff and the policy role of ministers and the Prime Minister in particular became even more important. Suspicion of high public servants hardened.

A bi-partisan consensus was developing that the policy agenda should belong to ministers; that ministers should be equipped to develop policy proposals and they should no longer be hostage to a lack of information, or to powerful public servants dictating what was and what was not acceptable. This process was accelerated further by the behaviour of one particular public servant, John Stone, who became Secretary to the Treasury after Fred Wheeler retired in 1978. Stone always saw great significance in the fact that he was Secretary to the Treasury, not the Treasurer. John Stone saw himself as an important player on the national stage, but had none of Fred Wheeler’s reassuring style with ministers.

Malcolm Fraser, as Prime Minister, appeared to be no instinctive supporter of Stone and had already expressed his displeasure at Treasury by splitting the department in 1976. The appointment of John Stone looks out of keeping with the times. However from today’s perspective it is easy to overlook Stone’s influence, particularly his influence with the media. I remember attending post-Budget functions in Parliament House during the Fraser years when government backbenchers would drop by with the explicit intention of asking Treasury officials ‘what did Stone think of the Budget?’ They assumed, and they were right to assume, that tomorrow’s headlines would be heavily influenced by Stone’s view. This was not a healthy state of affairs. Nor was it stable.

Ministers from both sides have made it their mission to make sure that Canberra does not see the likes of another John Stone. This process continues to this day through John Howard who was Treasurer during the Fraser years. I am sure that the history of the Public Service and processes in Canberra would have been quite different if Bill Cole had made it to the Secretary’s job in Treasury rather than John Stone.

Gough Whitlam started the process of providing ministers with staff. Malcolm Fraser validated this process but went one further. Fraser saw executive authority as residing very much with the Prime Minister and not with ministers. He reserved the right to second guess his colleagues, over-ride their decisions and dictate the direction of policy for the whole government. So was created the Prime Minister’s Office and an adviser structure that could oversee every area of government.

Malcolm Fraser put his imprint on the new Parliament House and his legacy is still very much with us. Ministers and their staff are not in their departments, they are in the Executive Wing of Parliament House. Ministerial Offices—with the exception of the office of the Deputy Prime Minister, which was designed for the Leader of the National Party—are relatively small with limited staff space. The Prime Minister’s Office is large with considerable space for staff. All successive prime ministers have been comfortable with the Fraser arrangements and the Prime Minister’s Office is now at the centre of government in this country. Visually impaired people call it the Oval Office.

During the Hawke–Keating years from 1983–1996, the Public Service continued to be reformed. There was increased focus on ‘letting the managers manage’, performance assessment and making the Public Service more efficient and accountable and more responsive to the needs of government and its customers. Early on, John Dawkins as Finance Minister removed the permanency of departmental Secretaries which lined Secretaries to departments, and gave ministers an involvement in the administration of their departments. Bob Hawke and Mike Codd amalgamated departments, and Secretaries found themselves answerable to multiple ministers. Towards the end of the period, Secretaries lost tenure and were put on rolling contracts as part of a pay settlement. Losing tenure and a subsequent move in the Howard years to put Secretaries onto fixed term contracts, appears to have had the biggest impact on behaviour, reducing the willingness of Secretaries to speak up even within the confines of the Public Service itself.

The Public Service was given a key role during the Hawke–Keating years, but it was different from the role it played during the Wheeler years. The Public Service was expected to work with the government but in a way that was productive and harmonious for both sides. During this period, departmental Secretaries continued to be people of standing who commanded respect not only with the Cabinet but also with the Parliament and the community.

The growing power of the Prime Minister and his Office brought more influence to the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Mike Codd under Bob Hawke, and Mike Keating under Paul Keating, had a major impact on the way processes in Canberra worked and the standing that was given to public servants. Both Mike Codd and Mike Keating were professional high-calibre Commonwealth public servants and would have been recognisable to their equivalents in the British Civil Service. When Paul Keating lost office in 1996, the new Prime Minister, John Howard, replaced Mike Keating with Max Moore-Wilton. Max Moore-Wilton was a state public servant and is someone altogether different from the Codd-Mike Keating types.

Looking back on my experience with the Public Service, it is clear that prime ministers, and to an extent treasurers, set the tone. Chifley created the career of Nugget Coombs and the post World War Two elite in Canberra because he liked being surrounded by clever people who could do things. Chifley was also doubtful about the capabilities of some of his Cabinet colleagues.

Menzies inherited Chifley’s Public Service and he too was comfortable surrounded by talented people. Menzies too was doubtful about the quality of his Cabinet. To Menzies it was preferable to have power in Canberra tied up in the hands of a senior cadre of talented high officials answerable to him, than to have it dissipated through a collection of ministers for whom he had only modest regard. Indirectly, Menzies therefore created Fred Wheeler’s generation of public servants.

Hawke empowered Mike Codd because, unlike Whitlam, Hawke wanted to run a government firmly wedded to due process. Paul Keating empowered Mike Keating because he wanted to run a somewhat more activist agenda but he too was wedded to due process. The only senior public servant who was not validated by a Prime Minister was John Stone. Max Moore-Wilton has been empowered by the current Prime Minister to make sure that we never see another John Stone.

Paul Keating actually liked public servants and respected their commitment to good policy and the national interest. He always had the highest regard for what he called the ‘official family’ and was keen that they be allowed to do their jobs. As he said in 1991 in his Higgins Memorial Address to the Economics Society:

Lying behind the talents of individual Cabinet ministers is an overall philosophic belief that the expertise of the Public Service needs to be explicitly and deliberately brought to bear on policy matters.

… the critical point is that from the very beginning this Government has been very concerned about due process. And due process has meant that the Government has valued official advice and made sure that the institutions that provide it are strong and effective.

It is why this Government has always believed in a career Public Service, capable of giving independent advice. It is why the Government has not sought to shield itself from critical advice by appointing ‘friendly voices’ to key positions.

As many Governments have found to their cost … it is fatal to good government if ministers do not listen to, or are not served by, a strong Public Service.

But Paul Keating was also a firm believer in the constructive role of politicians. Unlike a number of earlier prime ministers, Keating saw an important role for his Cabinet colleagues. Again quoting from his Higgins Memorial Address:

While many decry the role that politicians play, only politicians can make major changes to the way a country conducts its business …

In the end, politicians have to have the foresight to see the need for change and the courage and strength to carry it through.

And the issues are now so complex and the areas requiring change so wide that it is far beyond any individual political figure to control the whole process.

This is why a strong and practical Cabinet is absolutely essential for Australia at present and will be so for years to come.

A Cabinet made up of lightweight figures confused about policy priorities and equipped with little more than rhetoric and ideology would produce a disastrous outcome for the nation.[1]

To be effective, Cabinet ministers had to have staff as well as the support of a strong department. Through the Hawke–Keating years the role of ministerial staff and the Prime Minister’s Office, in particular, continued to grow. The Prime Minister’s staff had particular standing because of their role in directing and coordinating the staff of other ministers and in coordinating ministers themselves. John Howard therefore inherited a powerful structure of ministerial staff and a Public Service that saw itself as having independent standing.

Howard has maintained the practice of most of the Hawke–Keating years of having a strong Treasurer with a good working relationship with his department. This has been something of a balance to the power of the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office. However, prime ministers do not always welcome strong treasurers and such arrangements need not be stable.

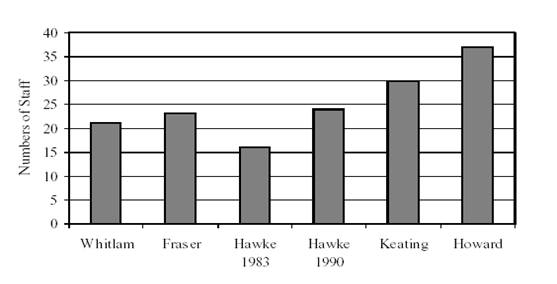

Staff numbers in the Prime Minister’s Office have continued to grow and Howard, like each Prime Minister before him, has operated with a larger staff than his predecessor. The numbers are set out in the following table taken from a research paper published by the Parliamentary Library.[2]

Staff in the Prime Minister’s Office

Neither Hawke nor Keating saw departments as extensions of the ministerial offices. The behaviour of staff was also constrained by the belief that they were personal appointments of the minister. As such, they were viewed as being inextricably linked to the minister. The working assumption was if a staffer was informed of something, then it was taken that the minister had been informed. In the years that I was responsible for Keating’s office, both as Treasurer and Prime Minister, we worked absolutely to this principle and as far as I am aware, this was the principle that guided the other offices. During my time in the Prime Minister’s Office, we would have brought into line any office that operated on a different principle.

Knowing that they carried the minister’s reputation in their hands was a powerful discipline on staff and on ministers. It was a particularly powerful discipline on staff in the Prime Minister’s Office because of their key role. With Hawke–Keating, it was hard for ministers to use staff as a way of avoiding scrutiny. It was also difficult to use them as a convenient buffer during times of trouble.

John Howard however has changed the balance of the Hawke–Keating years. Ministerial staff and the Prime Minister’s Office continue to grow in influence but because of the ‘Children Overboard’ incident, staff now can be viewed as leading an existence separate from that of their minister. Informing a staffer is no longer the same as informing a minister. We have entered a world where staff can carry much of the authority of the minister but can be disowned if necessary.

Ministers have to account for their actions to the Parliament at Question Time. By long standing arrangement, ministerial staff do not appear before Parliamentary Committees. It would appear that the Prime Minister and his ministers now have a new power. They have staff who can act on their behalf, who can be disowned if necessary and who are not accountable to the Parliament. This is a dangerous development.

As well, the independence and potential balancing role of the Public Service has declined. This was brought into stark relief in the case of the ‘Children Overboard’ incident. Fred Wheeler would not have been surprised by the behaviour of ministers and their staff. He would have seen them as only acting to type. What would have shocked Wheeler would have been the behaviour of the Public Service.

As Stone used to say: ‘Never underestimate the power of the written word.’ If Stone felt that his minister needed to know something, he would have had a red lined minute on the minister’s desk with copies to the minister assisting the next morning. Fred Wheeler would have rung; Bernie Fraser would have rung; Mike Keating would have rung and ministers would have accepted that they had every reason to ring.

It is not that the Public Service has become political; it has become acquiescent. As it is told around Canberra:

In the old days if the Secretary did not get on with the minister the minister moved. Then it became if the Secretary did not get on with the minister, the Secretary moved. Now if the Secretary does not get on with the minister, the Secretary gets sacked.

Unfortunately these 3 sentences, and what they signify, sum up the past 30 years all too accurately.

How do we make the system more balanced?

1. We should return to the Hawke–Keating practices with respect to ministerial staff. If staff continue to lead an existence separate from their minister, then staff should appear before parliamentary committees.

Under current arrangements, a potentially large part of ministerial influence and behaviour is beyond scrutiny. This is a new development with very bad long-term implications. From personal experience, I know the power that ministerial staff possess, particularly key staff in the Prime Minister’s Office. Under the Hawke–Keating arrangements, such power had to be exercised in a way that ministers could publicly acknowledge. Under current arrangements, ministerial staff can do things that ministers would find hard to justify, and this will inevitably lead to abuses. As ministers explore the full limits of their new discretion, we can be sure that these abuses will be major.

It is not fanciful to believe that we are taking the first steps down a path that leads to Haldeman and Ehrlichman, plausible deniability and the Nixon White House. If staff are separate from their minister, then the legitimate argument that staff are accountable to the minister and the minister is accountable to the Parliament loses its force. In such a situation the Senate, in its dealings with the government, is entitled to take whatever action it thinks most effective and which will bring ministerial staff back into a structure of accountability.

2. Tenure should be returned to Secretaries

Committees of Secretaries resolve opposing views within the Public Service. It is hard for Secretaries to speak their minds when they are on fixed term contracts and the person chairing the meeting is responsible for the terms of that contract.

3. The expertise and standing of the Public Service should be rebuilt

The characteristics of the Public Service are determined by the Prime Minister of the day. It will be hard to rebuild the Public Service, but with the right person in charge of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, it can be done. We should not return to the years of John Stone or Fred Wheeler but we do need to attract talented people of standing who wish to work in a cooperative and mutually satisfying way with government.

This will require positive support for Secretaries and their careers.

Much government activity is now outsourced and there are growing doubts about the ability of departments and staff to properly assess and evaluate outsourced programs now that in-house expertise has gone. The Public Service needs to have a capacity to provide expert advice on the full range of activities for which their ministers are responsible.

4. Where the capacity of the Public Service to scrutinise and evaluate programs is deteriorating, we should acknowledge the legitimate role of the Parliament to perform the task.

When people have confidence that government programs have been put together after a strenuous process of review and evaluation backed by an expert Public Service, then it is understandable to see the committee system of the Parliament as a burden. When this confidence disappears, program evaluation by the Parliament becomes an important and necessary task.

We have built into our system of government a High Court and a Senate modelled on their US counterparts. The original motive was to protect state interests but, as in the US, the effect has been to institutionalise a dispersal of power and create a chamber with strong review powers. Given the way in which executive power has evolved in this country and the growing complexity and diversity of our nation, these institutions should now be seen as assets.

Public Servants often find dealing with ministers and their staff stressful. However, it would appear that there is something particularly chilling about having to face a committee of the Parliament knowing that your behaviour in regard to some matter could be judged inadequate. Faced with a potentially difficult situation with a minister or their staff, the possibility of scrutiny by the Parliament can strengthen the resolve of even the most acquiescent public servant.

5. Make the Governor-General or an Australian head of state responsible for good government

It has become clear that, apart from the Senate and the High Court, balance is not ‘hard wired’ into our system. The checks and balances on executive power are to an important extent self-imposed and dependent on the Prime Minister of the day. The power of the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office has been growing for the past 25 years, a trend that shows every sign of continuing. This means that the scope for the Prime Minister to have a major impact on how our system works has also been growing.

There is a tendency in our system for people to explore the limits of convention and due process. This means that, unlike the British, who appear to work well with ambiguity, we appear to be more like the Americans and require explicit structures. It is possible that we can make our current arrangements work better. We may be able to reinvigorate our Public Service and bring ministerial staff back into a structure of accountability. However it is also possible that things may continue to deteriorate and a consensus may develop that we can do better. If that were to happen, we would need to look to some structural change. However, it is hard to create new institutions or modify existing ones.

Given that the nation has recently explored the question of an Australian head of state, a consensus could develop that the Governor-General or an Australian head of state could use the black-print oversight powers of our Constitution, previously reserved for the British, to take a more active interest in good government. There would appear to be scope for Secretaries to hold their positions at the pleasure of the Governor-General or an Australian head of state and that could help invigorate the Public Service. If this were to happen it would require legislation. Likewise ministers could hold their positions at the pleasure of the Governor-General or an Australian head of state. Such a change could make ministers more interested in good government. The dormant black-print provisions of the Constitution already provide for this but they could be activated.

All these measures would involve some check on the power of the Prime Minister. The important point is that because of the recent debate on an Australian head of state or President, our system is potentially still evolving. There is therefore scope for the debate to move on and include the notion that an Australian President should have some responsibility for good government. If such a debate were to develop, we might find prime ministers taking an increased interest in making our existing structures work better.

Question — Regarding your recommendation that Parliament oversees the effectiveness of programs, we have already had examples of Chris Barrie and Jane Halton simply toughing it out in front of Senate committees. It seems that all we are doing is encouraging a tougher breed of public servant.

Don Russell — They were pretty tough in the past, I can tell you that. I think it is still very sobering for senior public servants to have to front parliamentary committees. It is quite an unnerving experience to do this publicly. A lot of public servants have their reputations and their careers to consider. So why are they doing this? It’s because they believe they are doing worthwhile things. An inability to account for yourself in front of Parliament can actually do very damaging things to your reputation. You can find that, after spending 20 or 30 years working on something you are proud of and building a reputation, that one incident where you can’t account for how you behaved—which is examined under the spotlight of not only the Parliament’s attention but also the attention of the media and your colleagues—can have a diabolical effect on your reputation.

So, sure, they may develop techniques for handling senators—although my experience is that senators very quickly develop quite a dramatic ability to put civil servants on the spot. I’m not sure how the setup here works, but looking at this committee room, which seems to be modelled on the US Senate, the witnesses always sit down below the level of the senators, who sit on high and look down on the witnesses. And the witnesses normally sit on ordinary chairs, and the senators always have their bodies partly of fully hidden. It is a very unnerving situation. And the more it happens and the more the nation believes that what is happening in the parliamentary committee is important, the more the public servants who come to be scrutinised by it will feel that they have to deal with it in an honest manner—because at the end of the day, the reputation of a public servant is important to them, and they basically can only look after that.

Question — In your suggestions for reform, you didn’t refer at all to the role of the Auditor-General. Would you care to comment on that?

Don Russell — The Auditor-General is one of the bodies that I didn’t cover here. You could consider having that body accountable to the Governor-General or a head of state, in the same sense, presumably, that you would have all sorts of relationships with the government of the day, but it would just give an extra degree of independence if their position was protected in some way by the Governor-General. It would be very similar to departmental secretaries. That would be a natural body to give an oversight role.

Question — If we don’t rein in the power of the PM’s office and their staff, what avenue do ordinary people have to address the excesses, apart from trying to take those staffers to the High Court?

Don Russell — I think this is very much a case where the peoples’ representatives are the agents. This is something that has to be dealt with within the parliament, and therefore people, and the electorate at large, have to recognise that there is a problem, and that this is an issue—that the power of the Prime Minister and the Prime Minister’s Office is something that we should think about, and think about whether it is properly balanced. In the past it has been balanced by an independent Public Service, and that balance seemed to work quite well. But if the power of an independent Public Service starts to dissipate, then you are left with what I would see as a structural problem. But I think the agents have to be the peoples’ representatives and the people themselves have to come to the conclusion that this is a problem that needs to be addressed.

Question — I agreed with about 90 per cent of what you said. One question from the other 10 per cent relates to your suggestion of an enhanced role for the Governor-General. I’m concerned about the question of how the Governor-General would be selected. If he has the role you’re suggesting, he’s going to have much more power and I would have thought that the role would then become politicised. How would you see that being handled?

Don Russell — Once we start thinking about that sort of structure we come into a very complex set of issues. The starting point is really two-fold. One, to acknowledge that there is a problem, and that the system could operate more effectively. And if we get to that point, then we need to think of how we might handle that problem in a structural sense. And if we feel that the Governor-General or the head of state could have a role in good government—that the head of state would be more than just a figurehead—that’s the next step. If you pass both of those steps then I think we’re into a very complicated debate with the Parliament and the people as to what that actually entails, because we’ve been through the republic debate already, which raised lots of issues. Those two propositions have to be established first before we start to talk about what we really want in terms of the nature of the head of state or the Governor-General.

Question — Can you go that route without going all the way to an American-style system? Although there may be something to be said for that.

Don Russell — No, I think we are actually quite blessed. The American system has gone too far in the other direction. They have put in place so many checks and balances that the system is geared to the status quo. In American that doesn’t matter so much, because it is so big, the system just somehow adjusts. They don’t really care or need an effective government. I don’t think we have that luxury, we always have to have an effective executive and an effective government in this country, because we don’t have the luxury of just letting things evolve. There are very clear benefits for a country of our size having an effective government that can do things. So heading towards a totally American system would be a mistake for this country. We actually have the benefits of the parliamentary system and the benefits of the review processes of the US system. So we may well be able to craft something particularly useful for this country, taking advantage of what we’ve got and building into our system a flexibility and an accountability that other systems don’t have.

The New Zealanders have a unicameral system—or they used to have a unicameral system, with first-past-the-post voting. That was a winner-take-all system of the highest order, and it exhausted them, and now that they have locked themselves into proportional voting they have locked themselves into a status quo system which I think will not serve them well. Whereas, because we have always had some balance in our system, and because we have preferential voting, we may well be able to craft something that keeps the flexibility of having some dispersion of power while keeping core effective government at the same time.

Question — I am a supporter of your views on the head of state issue. You’ve covered that fairly well, and I assume you wouldn’t see as a good idea the present system where the Prime Minister appoints the head of state?

Don Russell — That would have drawbacks. We could evolve a convention where he may still appoint the Governor-General. This is leaping down the track a long way, and there are all sorts of alternatives that we could use if we were going to use that position as being responsible for good government. It’s not inconceivable to have the Prime Minister appoint a person, as long as the tradition and the expectation is that the Governor-General will exercise these powers, because even though, under the current arrangement, the Prime Minister can dismiss Governors-General, it is a big thing to do. Prime ministers really don’t want to dismiss Governors-General just because they are becoming difficult. It does look bad.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 25 October 2002.

[1] Paul Keating, ‘The Challenge of public policy in Australia’, inaugural Higgins Memorial Lecture, 15 May 1991. Published in the Canberra Bulletin of Public Administration, no. 65, July 1991: 16–20.

[2] ‘Accountability of ministerial staff?’ prepared by Dr Ian Holland, Research Paper 19, 2001–02.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top