Andrew Moore *

It has been a big year for anniversaries. Apart from the big one, the centenary of ANZAC and Gallipoli, among them is the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II and related events of 1945, the release of prisoners from German concentration camps, and the Yalta and Potsdam conferences. It is also the centenary of the birth of the great Australian poet, Judith Wright, and in May 2015 there have been events to celebrate her life in Braidwood and Tamborine Mountain.

Most relevant here, however, among the anniversaries of note, is the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta of 1215. As Nick Cowdery, the former New South Wales Director of Public Prosecutions, argued at a recent conference in Sydney, from it we take the rule of law, the separation of powers, the principles of democracy, the presumption of innocence, the onus of proof, trial by jury, access to justice and much more.

Relatedly, it is also sixty years since the privilege case of Fitzpatrick and Browne when many of these noble principles were cast aside. In 1955 the working-class south-west Sydney suburb of Bankstown was the centre stage of Australian politics. Bankstown’s local affairs were highlighted in all the major newspapers around Australia as well as internationally in papers like the Manchester Guardian and the London Times.

The issue, a celebrated event in Australian constitutional, political and legal history, involved the gaoling by the Commonwealth Parliament, specifically by the House of Representatives, of two individuals. One was a local Bankstown businessman and newspaper proprietor, Ray Fitzpatrick. The other was the journalist he employed, Frank Browne. Their crime was arcane: contempt of parliament, a crime of which most Australians, let alone Fitzpatrick and Browne, as well as most members of the fourth estate, had not heard.

I want to do three things this afternoon. First, I need to describe the sequence of events for they are not generally well remembered. I also think that understanding the background of events leading up to the privilege case is the key to understanding the privilege case of 1955. Second, I want to examine how the events may be interpreted. Here I propose to follow the historiographical parameters provided by two distinguished servants of this parliament and of democracy, Frank Green, Clerk of the House of the House of Representatives from 1937 to 1955 and Harry Evans, Clerk of the Senate between 1988 and 2009. Finally, I want to conclude with some of the legacies that may be gleaned from Fitzpatrick and Browne after 60 years. I note the interesting point that historian David Walker makes that the most important anniversaries in China follow a 60-year cycle, marking the journey to wisdom over a lifetime.1 What, if anything, after 60 years have we learned from Fitzpatrick and Browne?

The beginning of the story, if not its background which I will come to in a minute, was on 28 April 1955 when the Bankstown Observer, owned by Ray Fitzpatrick, attacked the local MP in the Commonwealth Parliament, Charlie Morgan. The suggestion was that he (Morgan) had been involved in a series of ‘immigration rackets’. The information came from a leaked security service report. The matter was an historical one. It pertained to events nearly twenty years earlier when Morgan worked as an immigration agent, although the way the article was framed made it seem a current matter.

Charles Morgan, Member for Reid in the House of Representatives, 1940–46 and 1949–58

At this point Charlie Morgan had the option, of course, of pursuing legal action for defamation. Instead he took an unusual course of action. Morgan claimed that he was being intimidated and therefore could not perform his duties as a member of parliament. The implication was that he was being bludgeoned into silence. Seen in that light the matter was capable of being construed as a contempt of parliament. If one parliamentarian could not do his job—to speak his mind without fear or favour—parliament itself was undermined.

Morgan was able to convince first his colleagues in the House Privileges Committee that this was indeed an act of contempt of parliament. Then it went to members of the House of Representatives, who concurred. On 10 June 1955, sometimes known as ‘Black Friday’, the honourable members decided by a margin of 55 to 11 (in the case of Browne) and 55 to 12 in the case of Fitzpatrick to commit the ‘Bankstown Two’ to three months in gaol. Much of their incarceration was served in Goulburn Gaol, admittedly not the grisly high-security penitentiary it has become in more recent years, but certainly the coldest gaol in New South Wales and not the most pleasant place to be at the height of winter.

When I tell this story people often wait for some reference to the court process. Perhaps, they assume, I have forgotten to mention what the legal judicial system had to say about the matter. But this had nothing to do with the courts. Instead parliament was judge, jury and prosecutor. It is true that both the High Court of Australia and the Privy Council in London considered the matter. But in dispute in those forums was not the rights and wrongs of the decision to commit, but about the constitutionality of the process. (Section 49 of the Australian Constitution states that the powers and privileges held by the British Parliament in 1901 are replicated in Australia.)

This was the first, the last, and the only time in Australian history this has happened. Clearly it is an issue that relates to political history, legal history and constitutional history.

Less obviously, it was an event to do with Labor history, curiously the residue of the Lang Labor split of 1931, more than the ongoing B.A. Santamaria/Grouper split in the ALP of 1954–55. In his few appearances in the secondary sources, Ray Fitzpatrick is usually described as a Langite, meaning a supporter of the former NSW Premier, J.T. Lang, and his quixotic career as MHR for Reid between 1946 and 1949. Quite possibly it would be more appropriate to describe Jack Lang as a Fitzpatrickite. Ray Fitzpatrick had many do his bidding in a number of jurisdictions. This included state and federal politicians. Lang, the ‘Big Fella’, was one of Ray Fitzpatrick’s envoys in Canberra.

The Fitzpatrick and Browne affair was also a reflection of the local history of the suburb of Bankstown. Indeed I believe that understanding events in Bankstown is the key to understanding the privilege case.

After World War II Bankstown was bursting at the seams. Factories were relocating from the inner city at a great pace. There was massive suburban growth. The municipality’s population increased by 7,000 a year. Bankstown rejoiced in its reputation as the ‘Birmingham of Australia’. It was also known as the ‘wild west’ and ‘another Chicago’. How Bankstown acquired that reputation had a great deal to do with one of the central characters in the privilege case, Raymond Fitzpatrick, known locally, predictably enough, as ‘Fitzie’ and in the media as ‘Mr Big of Bankstown’.

Ray Fitzpatrick was a 1950s underbelly-style gangster. To be fair he did not simply rely on intimidation. There was general respect for a working-class local made good. He was a big employer in the area and not ungenerous to local charities. The basis of Fitzpatrick’s growing business and property empire, the legitimate part of it anyway, was in construction, sand and gravel, trucks and dozers.

It would take all of my time today to describe Fitzpatrick’s many calumnies. Suffice it to say that he was congenitally corrupt, especially as far as Bankstown Council and its contracts were concerned. At least, however, unlike gangsters and the drug barons of the 1960s who used ‘shooters’ and goons, Fitzie used his own fists, occasionally crowbars; he was his own enforcer. His brothers were also big, rough, hulking men so he did not need hirelings. In any case if there was a lurk or a short cut on offer, a council, a policeman, politician or public official, even a judge, to be bribed, Fitzie was the likely perpetrator.

Leading up to the privilege case Bankstown had become a ‘maelstrom of malevolence’, an apt description coined by one of my informants, the late C.J. McKenzie who briefly worked for Fitzpatrick on the Bankstown Observer. There was a broad fault line in the community related to support or opposition to Ray Fitzpatrick; thus there were the Fitzpatrickites and the anti-Fitzpatrickites.

Ray Fitzpatrick’s major opponent, both in this instance, as well as more generally, was Charlie Morgan, MHR for Reid from the 1940s to the late 1950s. Morgan was an excellent local politician but in national politics an inconspicuous figure. Had the privilege case not occurred more than likely he would be totally forgotten. Initially Fitzie and Morgan were mates. Their relations were congenial until World War II when various constituents made Morgan aware of Fitzie’s corrupt practices. Fitzie’s role in building Bankstown airport was particularly inglorious. Among other things he purloined an aircraft hangar and erected it in central Bankstown to house his trucks. Morgan named Fitzpatrick in the Commonwealth Parliament as a war profiteer and corrupt businessman. Ray Fitzpatrick, unsurprisingly, was outraged. One of his responses was to organise Jack Lang to take the seat off Morgan in 1946. Morgan won the seat back in 1949.

At this stage, in 1949, Morgan and Fitzpatrick seem to have organised a truce but it did not last. It was a long and complicated path to Goulburn Gaol, but suffice it to say that the turning point was the burning down of Bankstown’s other newspaper, the eponymous Bankstown Torch, owned by the redoubtable Engisch family, on 11 April 1955.

Charlie Morgan fired up, firstly in parliament, accusing Fitzie of instituting a reign of ‘terrorism and gangsterism’ in Bankstown. Initially he alluded to the sinister role of a certain ‘Mr Big’ but then named him. The national media began hyperventilating.

Understandably Ray Fitzpatrick was not at all impressed by all this nationwide publicity. Nonetheless, given the allegations that he was a gangster, even an unsophisticated Bankstown businessman could work out it was inappropriate to work over the local parliamentarian with a tyre lever.

Instead, Fitzie’s response was to engage the services of Frank Browne, a hard-bitten, hard-drinking journalist of far right-wing persuasion to write for the Bankstown Observer. Fitzie wanted, he told Browne, to ‘get stuck into’ Morgan.

Browne was best known for his scandal sheet Things I Hear which regularly defamed parliamentarians on all sides of the house. According to ASIO, Browne also used Things I Hear as an instrument of blackmail. Frank Browne was a ratbag of the highest order. He was violent and mentally unbalanced. Emerging from gaol in 1955 he apparently suffered from the delusion that he was Adolf Hitler after the Munich beer hall putsch and set about organising a neo-Nazi political party, the Australian Party, with predictably desultory results.

So on 28 April 1955 the Bankstown Observer published the article written hastily by Browne referring to the series of so-called ‘immigration rackets’ Morgan had been involved with in 1939. The two three-month gaol sentences for contempt of parliament were the result.

Despite its singular character, the Fitzpatrick and Browne privilege case of 1955 remains poorly understood and remembered. Amnesia is a common malaise in Australia. Perhaps because other events of the Cold War—the Petrov espionage drama and the split in the ALP—seem more compelling, most general histories of Australia pass it by. John Howard’s account of his mentor, R.G. Menzies and his era, is only the most recent work that fails to mention the matter. Though there is now a full-length monograph published on the privilege case—my own Mr Big of Bankstown: The Scandalous Fitzpatrick and Browne Affair, and this was widely reviewed—what it really needs is another Underbelly-style television mini-series to break through the forgetfulness and the amnesia. (And indeed the story has all the ingredients for a gripping drama!)

For the most part the parameters of the debate about Fitzpatrick and Browne are still those articulated by Harry Evans on the one hand and Frank Green on the other. Harry Evans is right. This was a case of contempt, a little-known aspect of parliamentary procedure and a sanction dating back to the origins of representative government in England and the Bill of Rights of 1689. Article 9 of the Bill of Rights forms the basis of the principle of modern parliamentary privilege. Specifically, it declared that freedom of speech in parliament ‘ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament’. Such sentiments were reflected in the speech Prime Minister Menzies made after the House had decided to imprison Fitzpatrick and Browne. Menzies argued that parliament was ‘the flower of Australian democracy, and the degree to which this House preserves the freedom of its members to speak and to think will be the measure of its service to democracy’.[2] These are noble sentiments, but was Menzies being sincere?

For many years the received view of Fitzpatrick and Browne, oft repeated in various newspaper articles, is that advanced by Frank Green as part of his 1969 memoirs. This built on the contemporary advice the highly experienced parliamentary officer provided to the Committee of Privileges at the time that no infringement of privilege—or contempt—had taken place. The veteran Clerk of the House, however, was no fan of Prime Minister Menzies and this shaped his view of the privilege case. So did his disillusionment with the parliamentary process, in particular the growth of the power of the executive under Menzies. For Green, Fitzpatrick and Browne was the bitter end. Green now saw himself as ‘a failure and Parliament as something meaningless, just a “front” for the dead democracy’.[3] After eighteen years of dedicated service, Green left parliament a week after the committal of Fitzpatrick and Browne. A valedictory dinner was held on 17 June 1955. One of the entrées on the menu was ‘Fitzpatrick Fruit Cocktail’.

Fourteen years later Green’s anger had hardly abated, when, in retirement in Tasmania, he contemplated the events of 1955. Green makes it clear that these ‘disgraceful proceedings’ progressed to their unfortunate conclusion without his approval and against his specific advice. Green explains that he was puzzled by the lack of attention paid to his official advice arguing that no infringement of parliamentary privilege had taken place. All became clear when ‘two senior men’ in the press gallery alerted him to a particular article Browne had written about Menzies in Things I Hear three months before the privilege case.[4]

This pertained to a raw spot from the prime minister’s past. Hitherto an enthusiastic member of the Melbourne University Rifles, Menzies displayed a lack of military resolve in 1914 and had not enlisted. This was the issue Earle Page famously had used against Menzies in 1939. Frank Browne joined a significant queue of critics imputing that Menzies was a coward.

When confronted with this intelligence, Green, as he put it, ‘saw the light—Menzies was after revenge’.[5] In Green’s view Menzies and other politicians, including the then Deputy Leader of the Opposition, Arthur Calwell, were motivated by personal animus against Frank Browne. Seen in this way the primary target was Browne such that, to use a modern term, Ray Fitzpatrick’s gaoling was no more than ‘collateral damage’.

Harry Evans disputes Green’s interpretation of events with force and forensic precision. In a scholarly article published in 2003 and included in his writings on the parliamentary web site, Evans characterises Green’s account as unreliable and ‘confused comment’. Indeed Evans laments the fact that Green’s account ‘has unfortunately achieved the status of gospel on the affair’. According to Evans, Green had confused the issue of a ‘breach of privilege’ with ‘contempt of Parliament’. Evans is particularly disparaging of Green’s assessment that Prime Minister Menzies had been influenced by a desire to exact revenge against Browne. ‘That allegation’, Evans writes, ‘follows a long tradition of attributing the worst imaginable motives to Australian politicians’.[6]

Far less aggrieved about the civil liberties implications of the Fitzpatrick and Browne affair than Green, Evans invites his readers to consider the possibility that the Privileges Committee and the parliament correctly understood the nature of parliamentary privilege. Both Menzies and the Leader of the Opposition, Dr H.V. Evatt, Evans argues, were ‘eminent constitutionalists’. By inference, Evans suggests, they were above such shallow and mendacious motives as exacting revenge, too principled to have gaoled two individuals for reasons of personal malice. In Harry Evans’ view, Green denigrates the sincerity with which Menzies and his parliamentary colleagues genuinely believed that the sanctity of parliament was under attack. There were no ulterior motives. This was a clear-cut case of contempt of parliament, the terms of which, in Evans’ estimation, the Privileges Committee and the House correctly understood. Fitzpatrick and Browne got what they deserved. Who then is right? Evans or Green?

Notwithstanding the veracity of many of Harry Evans’ arguments, it is difficult to discount the possibility that revenge played a role in the proceedings. By the same token Frank Green’s version of events is unlikely. It seems highly improbable that one article alone drove Prime Minister Menzies. He was not that thin-skinned. More likely it was the long-term animosity between Browne and Menzies which underpinned the gaolings. They were old sparring partners and even rivals dating back to the days of the establishment of the Liberal Party in the 1940s.

Nonetheless, the view that parliament’s actions were shaped by malice against Frank Browne (and Fitzpatrick for that matter) is supported by a significant body of primary evidence. This is the forty-odd pages of Hansard reporting various honourable members’ contributions to the debate to gaol or fine them. In large part these speeches make alarming reading and fail to vindicate Menzies’ subsequent recollection of the parliamentary debate deciding Fitzpatrick and Browne’s fate as being ‘conducted for the most part, with one or two exceptions, on a remarkably high level’.[7]

If this were true, Harry Evans may well be right. On the contrary, however, and with some notable exceptions, the contributors to the debate paid scant attention to H.V. Evatt’s exhortation that they should proceed ‘judicially’[8], presumably meaning impartially. The notion that members were protecting the integrity and reputation of parliament was lost repeatedly.

There was a bipartisan, unseemly enthusiasm for revenge. The whole matter proceeded with indecent haste. Fitzpatrick and Browne were accused, tried and sentenced by their victims in an atmosphere of hatred. As journalist Alan Reid later remembered, ‘You could feel the waves of hate going out from the Parliament to Brownie standing at the Bar of the House’.[9] Nor did the Speaker of the House, the redoubtable A.G. Cameron, help. Fred Daly’s suggestion that he looked and behaved like Hanging Judge Jeffreys was far from flippant.[10]

Finally, we also have to ask the question whether Morgan was ever genuinely intimidated, whether or not he sincerely perceived himself to be silenced? It is doubtful whether he did. A wily local politician, Charlie Morgan had been involved in internecine feuding with Ray Fitzpatrick for eleven years. The ‘Mr Big of Bankstown’ had done his best to end Morgan’s career in the 1946 elections when, as campaign manager for the Jack Lang, he contrived to publish a damaging smear sheet raising the ‘immigration rackets’ allegations.

These were not merely similar allegations; they were precisely the same ones, derived from the same purloined security service report that was later recycled in the Bankstown Observer in 1955. Jack Lang, too, had repeated the allegations against Morgan from the safety of parliamentary privilege during his term in parliament as MHR for Reid. By 1955 there can have been few electors in Bankstown who were not apprised of the ancient charges against their generally popular local member. As Fitzpatrick colourfully put it, in Bankstown ‘the dogs are barking it’.[11]

Employing the contempt machinery against Fitzpatrick was simply a final throw of the dice to deal with a local rival. More than likely the tactic occurred to Morgan in 1954 when he became a member of the House Committee of Privileges and sat in adjudication of other cases, including one, ironically, involving Jack Lang. Certainly Morgan had reasons to be wary of Ray Fitzpatrick. Reputedly in the lead up to the privilege case he increased his household insurance and took precautions to ensure his family’s safety. In reality, however, having ‘Mr Big of Bankstown’ put away for three months really only increased the likelihood of a late night visit from the aggrieved Bankstown businessman and one or more of his brothers.

Ward O’Neill cartoon of Prime Minister R.G. Menzies lassoing journalist Frank Browne, 7 July 2000. National Library of Australia vn3582577.

Reproduced courtesy of Ward O’Neill.

In conclusion Harry Evans, in my view, takes too much of Morgan’s case at face value and does not say or know enough about the background. Because Charlie Morgan’s freedom of speech was not genuinely being attacked, neither was parliament’s and therefore this was not a genuine contempt of parliament. Frank Green is also wide of the mark. While there was a strong element of revenge, primarily the privilege case of 1955 concerned Charlie Morgan exacting retribution against Ray Fitzpatrick rather than Menzies (and Calwell et al) against Frank Browne.

The fault lines between Frank Green’s sense of moral outrage and Harry Evans’ view that this was a genuine contempt of parliament continue to shape contemporary understandings of the privilege case. Ward O’Neill’s 2000 cartoon features Menzies lassoing Frank Browne. Noteworthy are the gallows in the background and the bar of the House of Representatives in front of Browne, from which the journalist had delivered an impressive speech in his defence, invoking, among other things, Magna Carta.

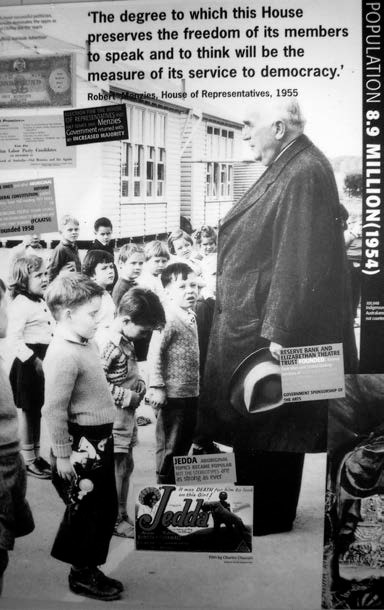

Harry Evans, on the other hand, would have approved of the version of history of Fitzpatrick and Browne featured in an exhibition in Old Parliament House in 2006. Perhaps he had something to do with commissioning it? In any case, to a group of attentive school children an avuncular Menzies revisits his rationale for the privilege case, deemed, for the purposes of the exhibition, to be the major statement of the entire year of 1955. The image was not contextualised but featured part of his ‘flower of democracy’ speech. Menzies’ justification for the events of 10 June 1955 is a reminder that as well as good intentions the road to hell is paved with noble sentiments.

Display panel at a 2006 exhibition at the Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House.

Image courtesy of Andrew Moore

If nothing else Fitzpatrick and Browne has inspired some excellent turns of phrase. Of the gaolings of the Bankstown Two, Gavin Souter suggested in his history of the Commonwealth Parliament that it ‘was rather as if the House had been annoyed by two blow-flies, and used its new Mace to swat them’.[12] Or as Enid Campbell, the Australian expert in the area of parliamentary privilege, suggests in a splendidly understated way, ‘the adjudication of parliamentary contempt cases leaves a great deal to be desired’, not least because, as happened in relation to Fitzpatrick and Browne, the ‘judges’ were ‘judges in their own cause’.[13]

Sixty years later Fitzpatrick and Browne remains of ongoing significance for those who care about civil liberties and free speech. It bears upon fundamental principles in a democracy, including the role of the executive branch of government, the importance of the rule of law and the separation of powers.

Menzies’ promise in 1955 to revisit and regularise the principles of parliamentary privilege was never delivered upon. In 1987 some ground was made in terms allowing more scope for judicial intervention to decide whether an offender’s behaviour constituted contempt, though the penalty was increased from three to six months gaol.

Even if the prospects for an encore performance of Fitzpatrick and Browne seem slim, as was suggested more than once in 1955, there is a need for a bill of rights to give legal effect to our basic freedoms for the first time.

Question — Can I just clarify something: did you say that there is a gaol built in this current Parliament House to house people and, if so, that it was built 30 years after this case and people had had plenty of time to digest it? Could you provide some context for that?

Rosemary Laing — I will offer to take that one. It’s possibly one of the big urban myths about this building. It was at one stage thought that there should be provision for holding cells in this building. You may even find plans with those areas marked, but they were never built, never proceeded with. I think they became electrical substations down in the bowels of the building. So it’s a great story; unfortunately it did not proceed into bricks and mortar.

Question — Could you please tell me what the reaction of B.A. Santamaria was to the setting up of the neo-Nazi party by Browne?

Andrew Moore — Well, not in any great detail, no. One of Frank Browne’s many gigs was to write an awful lot for Santamaria and for grouper publications. I think Frank Browne might have some claim to being one of the most interesting personalities of Australian history. He was a prolific journalist. He wrote for the groupers—not under his own name; he was just a wordsmith. He wrote for the People’s Union, an anti-communist group of that period. He wrote television reviews. He could never stop writing. He wasn’t ultimately a great fan of Santamaria. I think he made some denigratory remark about how they had a very short life expectancy, but he did write for the movement. I don’t know what Santamaria thought about that. He did work for the groupers, but then again he worked for almost everybody else as well. I think he might have written for most newspapers at some stage!

Question — My understanding is that after the event, most of the parliamentarians said something like ‘never again’.

Andrew Moore — Yes they did, and so did the press. I don’t think there was ever a great determination that it would never happen again from parliamentarians concerned. One of the principles that’s lying in the background here is the police ‘You was overdue, guv’ principle. That is to say it was widely assumed, for instance, that Frank Browne would end up in gaol for something that related to his work. So when it became a question of ‘Okay, is it right to send this ratbag to gaol?’, that tended to discourage a great deal of thought. I think it’s quite an ignominious affair by many parliamentarians, with one exception. One of those articles there is about Allan Fraser—but that’s not in the book or anywhere written; the book ended up being much shorter than what I hoped it would be—who was a parliamentarian who actually campaigned extraordinarily on civil liberties grounds against this ever happening again and nearly got chucked out of the Labor Party as a result of it. But most parliamentarians simply moved on to other things.

One of the things I should point out is that it happened on a Friday afternoon and, as the numbers would suggest, there was only a third of parliament actually there. They had all gone home. It was a day that was added to the parliamentary sitting and most parliamentarians had gone home on the Thursday, as parliamentarians do. So, again, there were not that many parliamentarians there.

I would say one of the reasons it has never happened again is there was an absolutely almighty barrage from the media and journalists, who had of course a vested interest, but nonetheless an appropriate vested interest, in that they thought, ‘Well, where does freedom of expression stand? Where does freedom of the press stand if these people have been sent to gaol?’ So there was an extraordinary campaign on those grounds. But I think most parliamentarians, apart from Fitzie’s mates, and Les Haylen was one of them, were probably pretty comfortable with what had happened.

Rosemary Laing — Can I add something to that, Andrew. I think today it would be unthinkable in either house for a penalty of imprisonment to be imposed on someone who was found guilty of contempt. Andrew, you mentioned the 1987 legislation and I want to be a pedant here. It wasn’t Hawke Government legislation. It was actually introduced by the then President of the Senate; it was a private senator’s bill. It was a parliamentary initiative and it became the Parliamentary Privileges Act 1987 and that Act did a number of things. It did have a direct link back to the Fitzpatrick and Browne case because when Browne and Fitzpatrick applied for writs of habeas corpus the High Court heard the matter and decided that they respected the law of parliamentary privilege and the right of a house of parliament to run its own affairs and protect its own patch, as contempt of court protects the patch of the courts. The High Court said, ‘We won’t look behind the warrant of the Speaker committing these men to prison,’ and the warrant of the Speaker simply said that they had been found guilty of contempt and were committed. So what the 1987 Act did was to say that where a presiding officer issues a warrant to commit people to prison for contempt, the warrant will specify what the contempt was and that will then allow the courts to come in and review that, whereas the courts didn’t really have any say in this matter because it was entirely a parliamentary question of protecting its own powers and immunities. So that was a little footnote, but I think such a penalty today would be unthinkable.

Question — What happened to Fitzpatrick after he left prison? And did he remain a force in Bankstown and for how long?

Andrew Moore — That’s a good question. He didn’t live that long. He was a heavy drinker already and gaol did not help that. Indeed, interestingly, you could apparently get a bottle of whiskey a day in the Canberra police station lockup with no problem at all, so he drank that. He was never going to live to a ripe old age. I think actually he transformed himself to a degree. As far as I can gather, he made a huge amount of money out of property investment, and still to the present day there is money to be made in property investment that is partly to do with Ray Fitzpatrick’s legacy. But he, I think, became more straight than not, and indeed his problem in the future was trying to get Bankstown Council, for instance, to have any dealings with him. Rather than actually being partial towards him, they would see the words ‘Ray Fitzpatrick’ and assume it would be a bad idea to have a business relationship with Ray. But he then went on and made squillions out of legitimate business. He built a very lucrative farm and, as I said, property empire. He kept going with what he was doing. He probably made more money out of straight—well, what I take to be straight—business than he did out of being a shonk.

Question —Just a follow-up: what happened to Browne afterwards?

Andrew Moore — Well, he started Australia’s first neo-Nazi party and that didn’t go down very well. He had a few supporters. He had a very colourful career afterwards. For instance, one of the colourful bits is that he goes off to fight in Rhodesia for white minority rule there in 1977. He is 62. I always think, ‘That’s my age and I wouldn’t care to be off fighting or doing anything in Rhodesia at that age’. He came back and was associated in the late 1970s with various neo-Nazi right-wing groups, nationalist groups, in Sydney, who were very pleased to get him because he was a major figurehead for the right. But he also had this strange other life. He could run perfectly legitimate businesses as a journalist and he continued to run Things I Hear, which Sir John Gorton later called ‘Things I Smear’, but it was a pretty good journal of record, and he could also conduct business deals. Then again, as I said, he had this other strange career as a nutter, a real right-wing ratbag, and I only really got interested in him because I’m interested in right-wing ratbags. But he then dies and, if you want some sense of schadenfreude, he dies totally alone in a squalid little flat in Kings Cross having drunk himself to death. So that was the end of him.

Question — Is a proportion of our perception of these events formed by contemporary journalists being outraged by another contemporary journalist being victimised?

Andrew Moore — I would say so, yes. When you read the newspapers of the time, I think it is one of the few issues where the Tribune, the far left of politics, agreed with the far right or the conservative end of politics with the Herald and The Argus and The Age. I mean there can’t have been more universal opposition to this. I think the only person who thought that it was a good idea was Francis James. The rest of the press was very strongly against the whole issue. Is it an enduring impression? It probably is. They are all preserved in the National Archives too, of course, so you don’t even have to do anything terribly adventurous to read a series of the newspapers. It was a major mobilisation against that act and it probably was another reason why it has never happened again.

I don’t know about you but, in terms of imputing violence, when Alan Jones had that incident talking about Julia and the chaff bag and throwing her into the sea, I thought that was contempt, if you like. I mean that’s contempt but is it a contempt of parliament? Probably not. Journalists, however, say whatever they want. As Allan Fraser pointed out, if the same rule applied, every journalist in the country had defamed the Chifley Government, so how come they didn’t end up in gaol?

Another thing I would say about it is that it is also about power and influence because it is significant that it was not a Fairfax or a Murdoch or a Packer that was put in gaol, but it was the editor of the Bankstown Observer. That is, this is a relatively small inconsequential villain who is the editor of a relatively small and inconsequential newspaper, and I think that’s another dimension to this. Arguably it wouldn’t have happened if it had been Sir Warwick Fairfax. I don’t think he would have done time in gaol. He would have had plenty of clever lawyers anyway to have got him out of it, but it is about that dimension as well I think.

Rosemary Laing — Interestingly, the 1987 Act abolished the contempt of defamation. So in a nice prefiguring of the discovery in the Constitution of an implied guarantee of freedom of political communication, the Parliamentary Privileges Act abolished that kind of conduct as a contempt. So there were no longer any of these contempt cases involving a naughty journalist saying something horrid about a member of parliament.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Canberra, on 29 May 2015.

[1] David Walker, ‘Know thy neighbour’, Griffith Review, no. 48, 2015, p. 195.

[2] House of Representatives Hansard, 10 June 1955, p. 1628.

[3] Frank C. Green, Servant of the House, Heinemann, Melbourne, 1969, p. 163.

[4] ibid., pp. 157, 159.

[5] ibid., p. 158.

[6] Harry Evans, ‘Fitzpatrick and Browne: imprisonment by a house of the parliament’, Papers on Parliament, no. 52, December 2009, pp. 136–7.

[7] Sir Robert Menzies, Afternoon Light: Some Memories of Men and Events, Cassell, Melbourne, 1967, p. 302.

[8] House of Representatives Hansard, 10 June 1955, p. 1630.

[9] Alan Reid, oral history recording (National Library of Australia) quoted in C.J. Lloyd, Parliament and the Press: The Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery 1901–88, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 1988, p. 201.

[10] Sun, 14 May 1976.

[11] Les Haylen, Twenty Years Hard Labor, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1969, p. 158.

[12] Gavin Souter, Acts of Parliament: A Narrative History of the Senate and House of Representatives, Commonwealth of Australia, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic., 1989, p. 431.

[13] Enid Campbell, Parliamentary Privilege, Federation Press, Sydney, 2003.