Key points

- The Treasury Laws Amendment (Financial Market Infrastructure and Other Measures) Bill 2024 (the Bill) implements two separate policy initiatives:

- to strengthen regulatory arrangements for Australia’s financial market infrastructure (FMI)

- to impose mandatory climate-related disclosure obligations on large businesses.

- Schedules 1, 2, 3 and 5 of the Bill implement an ‘important and longstanding recommendation’ of the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) to strengthen regulation of Australia’s FMI. The CFR’s recommendation has gained a new urgency following the failure of the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) to replace its decades-old CHESS system, which is a critical FMI that underpins the smooth functioning of Australia’s share market.

- Schedule 4 of the Bill empowers the Australian Accounting Standards Board to issue internationally aligned sustainability reporting standards that large Australian businesses and financial institutions must comply with. If enacted, large businesses will need to prepare an annual sustainability report to disclose their climate risks and opportunities in accordance with the new reporting standards. The Australian Government’s policy intention is to improve the quality and comparability of climate-related financial disclosures across different companies and sectors, which, in turn, should help investors make more informed decisions.

- The shift to mandatory climate financial disclosure has been described by government officials as ‘the biggest change to corporate reporting in a generation’ and has elicited strong reactions from a multitude of stakeholders. While environmental advocacy groups support the introduction of mandatory disclosure, several business groups are concerned that mandatory disclosure will impose ‘excessive regulatory burden’ on Australian businesses.

- In comparison with the widespread media reporting of Schedule 4, the policy initiative regarding FMI has garnered limited media attention. Written submissions from stakeholders indicate ‘overwhelmingly positive support’ for the FMI policy initiative.

- On 3 May 2024, the Senate Economics Legislation Committee published its report on the Bill and supported the Bill’s passage. Coalition Senators issued a dissenting report and raised concerns regarding several provisions of Schedule 4, recommending that these be amended.

Introductory Info

Date introduced: 27 March 2024

House: House of Representatives

Portfolio: Treasury

Commencement: As set out in the body of this Bills Digest

Purpose of the Bill

The Treasury

Laws Amendment (Financial Market Infrastructure and Other Measures) Bill 2024

(the Bill) gives legislative effect to two ‘important

reforms’:[1]

- Schedules 1, 2, 3 and 5 of the Bill introduce measures to

strengthen regulatory arrangements for Australia’s financial market

infrastructure [2]

- Schedule 4 of the Bill introduces a mandatory regime of

climate-related financial disclosure for large businesses and financial

institutions.[3]

The Bill makes changes primarily to the Corporations

Act 2001:

- Schedule 1 introduces the financial market infrastructure

crisis management and resolution regime

- Schedule 2 enhances the licencing, supervisory and

enforcement powers of ASIC and the RBA in relation to financial markets

- Schedule 3 makes changes in relation to the roles and

responsibilities between the Minister, ASIC and the RBA

- Schedule 4 implements the climate-related financial

reporting regime

- Schedule 5 makes various minor and technical amendments.[4]

History of the Bill and its

consultation processes

Prior to introducing the Bill in Parliament on 27 March

2024, the Government and financial regulators undertook multiple consultation

processes to gather feedback from stakeholders on the proposed reforms. The

consultation process resulted in two separate Exposure Draft Bills.

Consultation processes for mandatory climate disclosure

include:

Consultation processes for FMI regulatory reforms include:

The Bill that is subsequently introduced in Parliament

combines these two Exposure Drafts, effectively making it omnibus legislation.[5]

There are some differences between the Exposure Drafts and

the Bill, particularly in relation to the climate financial reporting regime

outlined in Schedule 4. The Treasury has indicated it plans to publish a table

detailing the outcomes of Exposure Draft Consultation.[6]

As the two reform initiatives are independent of each

other, the relevant background and key issues of the two initiatives are set

out separately in this Bills Digest.

Committee consideration

Senate Economics Legislation

Committee

On 3 May 2024, the Senate Economics Legislation Committee (chaired

by Labor Senator Jess Walsh) published its report on the Bill and recommended

the Bill be passed.[7]

Coalition Senators (Senators Andrew Bragg and Dean Smith)

made a dissenting report and raised concerns about several aspects of the Bill. [8]

They made 7 recommendations, 6 of which concerned the proposed climate

financial disclosure regime.

Senator Nick McKim of the Australian Greens and Senator

David Pocock (Independent Senator for the Australian Capital Territory) each

made additional comments about the Bill.

The Australian Greens asserted that a mandatory climate

disclosure regime is ‘long overdue’, but argued that several aspects of the

proposed regime must be amended to ensure a long-term framework that

disincentivises ‘greenwashing’.[9]

Independent Senator David Pocock made similar remarks that

‘the considerable positive changes in the Bill are undermined by the modified

liability regime in Schedule 4’.[10]

Details of the Coalition Senators’ dissenting report and

the Australian Greens’ additional comments are discussed in the ‘Policy

position of non-government parties’ section of this Digest.

Senate Selection of Bills

Committee

At its meeting of 27 March 2024, the Senate Selection of

Bills Committee noted that it had deferred consideration of the Bill until its

next meeting.[11]

Senate Standing Committee for

the Scrutiny of Bills

At the time of writing, the Bill had not been considered

by the Scrutiny of Bills Committee.[12]

Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights

As required under Part 3 of the Human Rights

(Parliamentary Scrutiny) Act 2011 (Cth), the Government has assessed

the Bill’s compatibility with the human rights and freedoms recognised or

declared in the international instruments listed in section 3 of that Act. The

Government considers that the Bill is compatible with human rights.[13]

Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights

The Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights had no

comment on the Bill.[14]

Schedule 4 – Mandatory Climate-related

Financial Disclosure

Background

What

is climate-related financial disclosure and why does it matter?

Climate-related financial disclosure refers to reporting

about how climate change could affect a company’s financial performance,

operations, and sustainability.

Climate change could affect a company’s financial

performance in many ways. For example, more frequent and severe weather events caused

by climate change could damage a company’s assets and disrupt its operations. Assets

or investments located in areas prone to natural disasters may also suffer

devaluation.[15]

In response to these financial risks, regulators expect

companies to implement robust risk management strategies and plans that address

both the risks and opportunities presented by climate change.[16]

As public awareness of climate change issues grows, there

has been a noticeable rise in shareholder activism, with investors increasingly

advocating for companies to disclose how they are affected by and managing

climate risks and opportunities.[17]

Furthermore, many investors ‘believe existing corporate

reporting contains at least some level of unsupported sustainability claims’ (a

practice known as greenwashing).[18]

As a result, investors are demanding better climate-related financial

disclosures so they can make more informed decisions about where to invest.[19]

A

variety of climate disclosure guidelines

A variety of climate disclosure

guidelines and standards currently exist in Australia and around the globe,

each equipped with its own distinct reporting requirements and styles. These

standards include Task Force on

Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), Sustainability Accounting Standards

Board standards, Global

Reporting Initiative standards, and Sustainable

Development Goals.[20]

Australian financial regulators have issued guidelines for

companies to voluntarily disclose their climate change related financial risks in

alignment with the TCFD framework.[21]

Currently, many large corporations listed on the Australian Securities Exchange

(ASX) prepare their sustainability and climate change reports in accordance

with the TCFD framework.[22]

However, the Australian Government notes there are

problems with existing climate financial disclosures by companies:

… existing climate risk disclosures are often inconsistent or

contain insufficient information to support decision-making. Investors also

note the lack of standardisation makes disclosures difficult to compare, which

impacts their decisions. …

The use of multiple frameworks, some voluntary and some

mandatory, alongside different reporting formats without any benchmark for

quality, means that users face a harder task in analysing sustainability

information. This ultimately leads to increased costs for users and

introduces inefficiencies into processes and eventually the market – leading to

misallocation of capital. …

Poor quality disclosures also increase the risk of

greenwashing.[23]

[emphasis added]

The Government considers Australian companies could become

less competitive in global capital markets if our climate disclosure regime

does not align with international best practice.[24]

Global

baseline for climate financial disclosures

In November 2021, the establishment

of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) was announced at

the United

Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP 26).[25]

The ISSB was created in response to a growing demand for more consistent and

comparable climate-related financial disclosures.[26]

This initiative for a global baseline for climate disclosures is supported by

G20 countries, which include Australia.[27]

Established as an independent standard-setting body under

the International Financial Reporting Standards

Foundation, the ISSB aims to develop sustainability reporting standards

that will establish a comprehensive global baseline of climate-related

financial disclosures that are ‘focused on the needs of investors and the

financial markets’.[28]

In June 2023, the ISSB issued its

inaugural standards:

The ISSB asserts that the 2 standards create a

common language for disclosing the effect of climate-related risks and

opportunities.[29]

The ISSB builds on the foundations of the TCFD, and it is arguable that the

ISSB standards are intended to be more prescriptive than the TCFD.[30]

Australian

Government’s commitment to introduce internationally aligned sustainability

reporting standards

In a policy position statement published in

December 2023, the Australian Government endorsed the adoption of the ISSB standards

in Australia, with modifications limited to ensuring the standards are

well-suited for Australia’s specific needs.[31]

This follows the Government’s commitment in its 2022–23 October Budget to

introduce internationally-aligned climate disclosure requirements.[32]

The Australian Accounting

Standards Board (AASB) is responsible for the drafting of the Australian

sustainability reporting standards that are expected to align as closely as

possible with the relevant standards issued by the ISSB.[33]

In other words, if enacted the Bill empowers the AASB to issue the final

Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards that will specify the details of

climate disclosure obligations for Australian companies.[34]

In

October 2023, the AASB released its draft standard SR1

Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards – Disclosure of Climate-related

Financial Information. The AASB and the Treasury anticipate that the reporting

standards will be finalised in the third quarter of 2024.[35]

The Government acknowledges that there will likely be some

implementation costs in imposing mandatory climate disclosure obligations on

companies.[36]

However, it also argues the benefit of having internationally aligned standards

is that the standards provide a baseline for information comparison.[37]

Furthermore, several other countries are developing their

own mandatory climate disclosure requirements in alignment with ISSB standards.[38]

As such, the Australian Government claims the implementation of internationally

aligned standards are ‘necessary to sustain Australia’s reputation as a

destination for the international capital that will be inevitably needed in the

transition to net zero’.[39]

Key

provisions and issues

Policy intention of the

mandatory climate disclosure regime

Schedule 4 of the Bill intends to provide investors with

greater transparency of a company or entity’s climate-related plans and

strategies.[40]

Specifically, the Government believes that greater transparency can be achieved

by improving the quality and comparability of disclosures of material climate-related

financial risks and opportunities within the financial reporting framework.[41]

Improved climate-related financial disclosures will also support regulators to

assess and manage systemic risks to the financial system.[42]

Overview of Schedule 4

To achieve these policy aims, Schedule 4 requires certain

entities to make climate-related financial disclosures in accordance with the

relevant AASB standards (also known as Australian

Sustainability Reporting Standards or ASRS). The new mandatory climate

reporting regime leverages the existing financial reporting regime set out

under Chapter 2M of the Corporations

Act 2001.[43]

Key aspects of Schedule 4 include:

- Mandatory

climate disclosures to be phased in over time: Entities under the Corporations

Act that meet certain minimum size thresholds and/or have emissions

reporting obligations under the National

Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (NGER) scheme will be required to disclose

their climate-related risks and opportunities.[44]

In other words, the proposed climate disclosure obligations are intended to

apply to large businesses and financial institutions only, and will be phased

in over time. However, there could be some flow-on effects for smaller

businesses.

- Sustainability

report: Companies will need to make their climate financial disclosures in a

new type of report called a ‘sustainability report’.[45]

The sustainability report will form part of an entity’s annual reporting

package that will be comprised of financial report, directors’ report,

auditor’s report, and sustainability report.[46]

- Auditing

and assurance requirements: Companies need to obtain audit and assurance

for their annual sustainability report. In other words, the auditor of a

sustainability report has the same obligations as the auditor of an annual

financial report.[47]

- Alignment

with global standards: Companies will be required to disclose their

climate-related financial risks and opportunities in line with AASB standards. The

AASB standards are expected to align as closely as possible with the relevant

standards issued by the ISSB.[48]

Figure 1: Overview of affected parties, timelines, and mechanisms

of the proposed climate-related financial disclosures

| Who |

What |

When |

How |

- Large

entities required to report under Chapter 2M of the Corporations Act.

- Entities

required to report under the NGER Act.

- Asset

owners with over $5 billion in assets under management.

|

- Climate-related

disclosures prepared in line with the Australian Sustainability Reporting

Standards (to be released by the AASB).

- Mandatory

reporting of Scope 1, 2 and 3 greenhouse gas emissions.

|

- Phased-in

approach for Groups 1, 2 and 3 entities.

- Group

1 entities required to commence climate disclosures from 1 January 2025.

- Limited

assurance requirements from Year 1, full reasonable assurance by 2030.

|

- Amendments

to the Corporations Act.

|

Source: Roohi Ghelani and Julian Soo, ‘A Closer Look at the Exposure Draft Legislation on

Climate-related Financial Disclosures in Australia’, (Anthesis Group), amended by the author of this

Bills Digest to reflect the differences between the Exposure Draft Bill and the Bill introduced into Parliament.

How many businesses will be

affected by the legislation?

The Treasury estimates at least 1,800 Australian

businesses and financial institutions will be mandated to disclose their

climate-related risks and opportunities under the proposed climate disclosure

regime.[49]

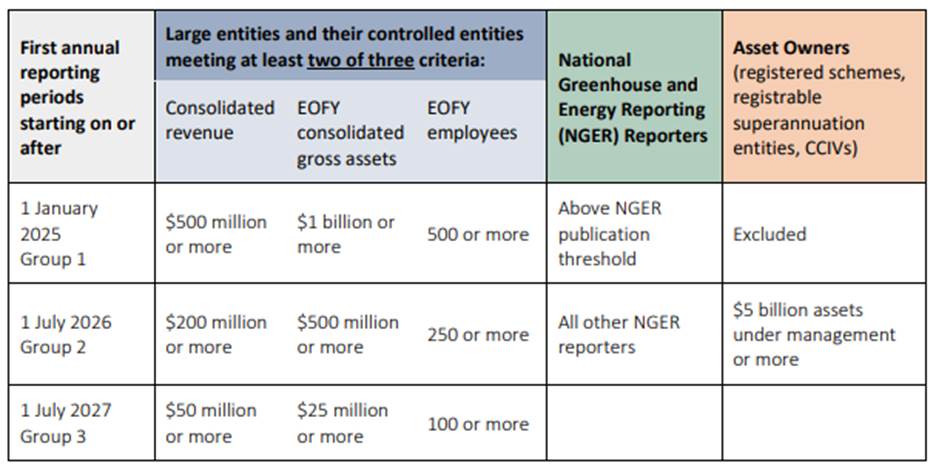

Affected businesses are categorised into three groups,

each with different thresholds for reporting. The specific thresholds for these

groups are based on criteria such as consolidated revenue, consolidated gross

assets, and the number of employees (see Figure 2).

Climate disclosure obligations for these 3 groups will be

gradually phased in, starting with the largest entities and progressively move

on to smaller large businesses.[50]

Figure 2: Thresholds for Group 1, 2 and 3 entities

Source: Treasury, ‘Mandatory climate-related financial disclosures: policy

position statement’, 2, amended by the

author of this Bills Digest to reflect the differences between the Exposure Draft Bill and the Bill introduced in Parliament. These changes include first annual reporting period

for Group 1 entities.

Based on Treasury analysis on 2021 data:[51]

- Group

1 is expected to capture at least 729 entities. The thresholds for inclusion in

Group 1 are broadly equivalent to the characteristics of the 200th company in

the ASX200.[52]

In other words, the expected size and revenue of companies in Group 1 would be

comparable to those large companies listed on the Australian Securities

Exchange (ASX). These large businesses may already voluntarily disclose their

climate risks in alignment with the TCFD framework. Furthermore, these large

businesses are likely to have the resources and expertise to meet their climate

disclosure obligations. Accordingly, Group 1 entities commence reporting from 1 January

2025.

- Group

2 is anticipated to include at least 755 entities. The thresholds for inclusion

in Group 2 are broadly equivalent to the characteristics of the 300th company

in the ASX300.[53]

The Government has clarified that asset owners, including

superannuation funds and investment schemes, are not classified as Group 1

entities even if they meet Group 1 thresholds. Instead, asset owners are

designated as Group 2 entities if their assets under management exceed $5

billion. Group 2 entities commence reporting from 1 July 2026.

- Group

3 is projected to encompass at least 278 entities. Prior to introducing the

Bill, the Government sought feedback on three potential options (known as

options 1, 1a, and 1b) for implementing the proposed mandatory climate

disclosure framework. At the time of writing, the Bill reflects option 1b.[54]

Under this option, Group 3 has a narrower coverage because the Bill contains a materiality

exemption for Group 3 entities. In other words, entities in Group 3 are

exempt from detailed climate-related financial disclosures if they can

demonstrate that they have no material climate-related risks or

opportunities.[55]

Group 3 entities that do have material climate risks commence reporting from 1

July 2027.

Which entities will not be

required to report under the mandatory regime?

Under the proposed climate disclosure regime, entities that

are already exempt from lodging a financial report under Chapter 2M of the Corporations

Act will not be obligated to prepare a sustainability report.[61]

These exempt entities include:

- small and medium-sized businesses or asset owners that do not

meet the thresholds outlined in Figure 2 (unless they are a NGER reporting

entity)

- an entity has been provided with relief or is exempt from

financial reporting by way of an ASIC class order or individual entity relief

- charity

and not-for-profit organisations.[62]

What kind of information

is required to be disclosed?

The Bill proposes that companies must make their

climate-related financial disclosure in an annual ‘sustainability report’.[63]

The annual sustainability report must include:

- a

climate statement for the year, including any notes made in relation to the

statement

- a

directors’ declaration that the statements comply with the Bill.[64]

The Minister may make a legislative instrument to require additional

statements and notes relating to sustainability-related financial matters to be

included as part of an entity’s annual sustainability report.[65]

An entity’s sustainability report is subject to mandatory auditing

and assurance processes.[66]

Climate statement

An entity’s climate statements must be prepared in line

with the relevant sustainability standards issued by the AASB (in other words,

ASRS). Whilst the ASRS is yet to be finalised, it is expected that an entity’s

climate statements must disclose:

- material

climate risks and opportunities faced by the entity (if any);

- the

entity’s governance process, strategy, and risk management plan about how to

manage climate-related risks and opportunities

- climate metrics and targets, including the entity’s Scope 1, 2

and 3 greenhouse gas emissions.[67]

Directors’ declaration

An entity’s annual sustainability report must include a

directors’ declaration that climate statements comply with the sustainability

standards specified in the Bill.[68]

However, the Bill introduces transitional provision for

directors’ declarations for the first three years. In other words, for the

first three years of the mandatory reporting regime, directors who are required

to provide a declaration will only need to declare that their reporting entity has

taken reasonable steps to ensure the substantive provisions of the

sustainability report are in accordance with the Bill.[69]

The transitional period may be intended to provide

directors enough time to build the necessary expertise needed for accurate

climate-related financial disclosures.

Auditing and assurance

requirements

An entity’s sustainability report is subject to mandatory auditing

and assurance processes.[70]

Similar to the phased-in approach of mandatory climate disclosures, the

sustainability report’s assurance requirements will also be phased in.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, ‘Initially, the

sustainability report will only be required to be reviewed or audited to the

extent required by the audit standards made by the Auditing and Assurance

Standards Board (AUASB)’.[71]

Over time, these auditing standards are expected to

develop further, which will enhance the scope of assurance required for climate

disclosures in the sustainability report.

On 20 March 2024, the AUASB released a consultation

paper to set out a pathway to phase in additional assurance requirements,

such that by no later than 1 July 2030 reasonable assurance will be required

for all climate disclosures.[72]

Modified liability for companies

making climate-related disclosures

Three-year protection for sustainability reports

Climate-related financial disclosures will be subject to

the existing liability framework embedded in the Corporations Act 2001

and the Australian

Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001 . These laws

address matters such as directors’ duties, misleading and deceptive conduct,

and general disclosure obligations.[73]

Currently, if a company makes a misleading climate-related

statement about future matters without reasonable grounds, then it could be in

breach of corporation laws.[74]

For example, in 2021 environmental advocacy groups sued Santos Ltd (an energy

company), alleging that Santos Ltd breached corporation laws and made false

claims about having a ‘clear and credible’ plan to achieve net zero emissions

by 2040.[75]

The Bill proposes a temporary modification in liability framework

for the first three years of the mandatory climate disclosure regime.[76]

This approach is known as ‘modified liability’ approach, and it provides

a transitional period during which entities can adjust to the new reporting

standards without the ‘threat’ of civil actions. Specifically, the modified

liability approach provides reporting entities protection or immunity from

civil actions for the first three years of sustainability reporting (other than

actions by ASIC).[77]

According to the Explanatory Memorandum, no legal action

may be brought against a reporting entity in relation to a ‘protected statement’.

Only ASIC will be able to take action for misleading and deceptive conduct in

relation to climate-related disclosures during the transitional period.[78]

Notably, the modified liability approach does not prevent criminal proceedings

brought by ASIC.[79]

For the purpose of the modified liability approach, a

protected statement is:

- a

statement made within a sustainability report within the first three years of

the disclosure regime

- an

auditor’s report of audits or reviews of sustainability reports about

- Scope

3 greenhouse gas emissions

- scenario

analysis made in those sustainability reports

- climate-related

transition plans or targets.[80]

The Government argues:

The policy intention [of modified liability] is to ensure

that during the transitional period, ASIC can undertake a role that promotes

education about compliance with the new reporting regime and deter poor

behaviours and reporting practices that are contrary to the objectives of the

new reporting regime.[81]

Several environmental advocacy groups have argued the

three-year immunity period is ‘unwise’.[82]

The groups advocate for the removal of modified liability (see the ‘Position of

major interest groups’ section of this Digest).

One-year protection for

forward-looking statements

One key difference between the Exposure Draft legislation

and the Bill introduced in Parliament is that the latter extends modified

liability protection for forward-looking statements.[86]

As part of their financial reporting, some companies make

forward-looking statements, which could include projections about the company’s

financial performance, how much the company’s assets could devalue due to

climate-related risks, how the company plans to achieve net zero emissions, et

cetera.

If an entity makes a forward-looking statement for the

purpose of complying with the relevant sustainability standards and auditing

standards, then the statement is protected from civil actions for 12 months.

The 12-month protection for forward-looking statements

overlaps with the 3-year protection noted above.[87]

The Australian Institute of Company Directors speculates the

rationale for the 12-month protection for forward-looking statements is:

Without the benefit of decades of established principles and

conventions, there is a heightened level of uncertainty relating to climate

disclosures which in relative terms, is still in its infancy. In particular, IFRS

S2 calls for highly company-specific disclosures which, under the

Treasury's current proposals, are currently either not assured, or only subject

to limited assurance.

Further, a significant number of IFRS S2 disclosures

will require prediction or estimation over long (5 to 10 year+) time horizons

and be subject to constantly changing assumptions due to changes in

decarbonisation trajectories, technological development and changing government

regulation. For instance, the future demand and projected revenue from a

product may be heavily subject to technological development.[88]

Position of major interest

groups

Over 120 stakeholders submitted written responses to the

Government in relation to the Exposure Draft Bill

for Schedule 4. Additionally, 26 stakeholders presented submissions

to Parliament regarding the Bill. Numerous stakeholders also indicated

their policy position in a Senate

public hearing about the Bill.

For conciseness, this Bills Digest highlights a few major arguments

from stakeholders, rather than examining every submission.

Environmental advocacy groups

Several environmental advocacy groups – including the Australian

Conservation Foundation, Environmental Defenders Office, Climate Integrity, and

Environmental Justice Australia – are broadly supportive of the Bill and

‘welcome the introduction of mandatory climate reporting requirements for large

businesses and financial institutions.’[90]

However, these environmental advocacy groups oppose

specific provisions of the Bill because they believe the provisions either

delay or undermine Australia’s carbon emission reduction goals. For instance,

Environmental Justice Australia (EJA) argues:

EJA is concerned that the proposed modified liability regime,

by removing the right of third parties (including investors) to hold entities

accountable for misleading and deceptive claims made in climate disclosures,

directly undermines the benefits of transparency that mandatory climate

reporting seeks to achieve. Without a corresponding right for third parties to

commence legal proceedings against entities for climate-related financial

disclosures that infringe the legislative requirements, the Bill lacks a

critical enforcement mechanism to ensure accountability. EJA submits that

this creates a heightened risk that these provisions of the Bill may actually

facilitate greenwashing claims that distract from and delay credible climate

action for a further three years, at this critical time.[91]

[emphasis added]

As such, the EJA and several other environmental groups

have recommended the removal of modified liability provisions from the Bill.[92]

Alternatively, Equity Generation Lawyers (a law firm that

specialises in climate laws) proposes reducing the scope of protection or

immunity provided by the modified liability provisions:

The immunity from private litigation should be limited to

civil proceedings for misleading or deceptive conduct that seek loss or damage.

…

Extending the immunity to more serious misconduct such as

negligent misstatement, breach of statutory duty, and breach of fiduciary

duties provides an unreasonable safe harbour from private litigation that does

not fulfil the goals of promoting investor confidence or improving Australia’s

reputation.[93]

In addition to concerns about the modified liability

approach, the Environmental Defenders Office (EDO) also opposes the delay of

the reporting commencement date for Group 1 entities.

In the Exposure Draft Bill, Group 1 entities would

commence mandatory climate reporting from 1 July 2024. However, the Bill

as introduced in Parliament delays the commencement date for Group 1 entities

to 1 January 2025 (or the first financial year that commences after that date).[94]

The Treasury argues the delay is to ensure entities have sufficient lead time

and the backstop is designed to avoid doubt around commencement arrangements

should legislation not pass this year.[95]

The EDO criticises the delay:

The EDO opposes the proposed delay of the commencement

date for Group 1 entities. Any delay in the commencement date further

compounds the material climate-related risks to the financial system. Further,

any delay will ensure that Australia falls further behind other comparable

jurisdictions which have already implemented equivalent reporting requirements.

… a significant proportion of Australia’s largest entities

have already adopted the practice of making voluntary disclosures against the

TCFD framework and are familiar with the GHG Protocol which inform the Bill.

Given the familiarity and experience with the disclosure requirements, there is

no reason to delay the commencement of the Bill.[96]

[emphasis original]

Business groups

Several business groups and their peak bodies have

expressed concern that the mandatory climate disclosure regime could create

‘excessive regulatory burden’ for Australian businesses.[97]

For example, Housing Industry Association (HIA) claims:

The Climate-related Financial Disclosure legislation requires

a separate Sustainability Report to be prepared, in addition to financial

statements.

This will greatly increase the administrative burden on

businesses without improving the quality of the information that is reported.

HIA is of the view submissions [sic] proposed reporting should be able to be

performed using a simple, consistent approach to disclosure, to reduce costs

and increase certainty for business.[98]

[emphasis added]

This sentiment is shared by the Australian Chamber of

Commerce and Industry (ACCI) and the National

Farmers’ Federation. The ACCI argues:

… there are elements of the climate-related financial

disclosure legislation that create a heavy administrative burden, are not fully

developed and represent substantial risk to business.

There are many important elements such as the AASB

Sustainability Standards, reporting of Scope 3 emissions and scenario analysis,

auditing and assurance requirements, as well as protections for businesses from

vexatious litigation, that are only partially developed or have not been fully

considered. These elements of the legislation represent a considerable risk for

entities require[d] to make climate-related financial disclosure.[99]

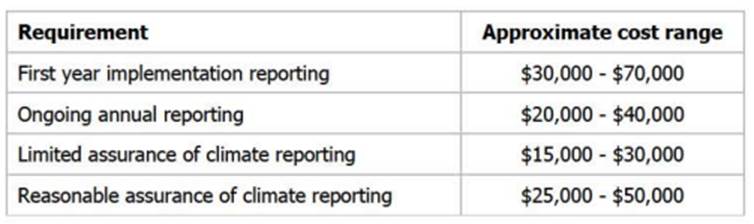

Nexia Australia, a business advisory firm, provides an

estimation of the compliance costs for Group 3 entities (see Figure 3) and

argues:

We consider that these costs would represent an excessive

regulatory burden on the majority of large proprietary companies and would

outweigh any perceived benefits to the Australian economy.[100]

Figure 3: estimation of the compliance costs for Group 3 entities

Source: Nexia Australia, Submission, 3.

In the Explanatory Memorandum, the Government acknowledges

that Schedule 4 is estimated to increase regulatory costs by $1.0 to $1.3

million per year per entity, averaged over 10 years.[101]

Academics

Academics from several universities – including Queensland

University of Technology and Swinburne University of Technology – have

expressed broad support for the mandatory climate disclosure regime. [102]

However, Professor Martina Linnenluecke

from the University of Technology Sydney is pessimistic about the potential

effect of the mandatory climate disclosure regime in driving corporate changes

because she considers that the Bill is merely ‘window dressing’:

These laws are meant to increase transparency about how

exposed companies are to risks from climate change, and will require companies

to look into and share what impact their activities have on the environment.

This, the government hopes, will accelerate change in the corporate sector.

But will it help lower emissions? I don’t think so. We

don’t have a carbon tax, which means many companies have no financial incentive

to actually lower their emissions. …

By themselves, climate disclosures will not trigger the

change we need.

… Critics have pointed out that reporting and disclosure

alone will not lead to a shift away from carbon-intensive business operations. Disclosures

give the appearance of action rather than real action. If there are no stronger

policies accompanying, disclosures act as window dressing for global financial

markets.[103]

[emphasis added]

Policy position of

non-government parties/independents

Coalition

As noted, the Senate Economics Legislation Committee (chaired

by Labor Senator Jess Walsh) recommended the Bill be passed.[104]

Coalition Senators Andrew Bragg and Dean Smith issued a dissenting report and

raised concerns about several aspects of Schedule 4.

Short timeframe to consider the Bill

In its submission to the Committee, the Law Council of

Australia raised concerns about the limited time given to review the Bill:

Significant concern has been expressed from all corners of

the legal profession about the extraordinarily short timeframe for this

inquiry. Regrettably, the inquiry period has overlapped with the Easter public

holiday period, and the due date for submissions was not published by the

Committee on its website until a week prior to the deadline. Compressed

inquiry timeframes undermine the democratic parliamentary process for the

proper scrutiny of bills.[105]

[emphasis added]

The introduction of mandatory climate disclosure has been

described by ASIC chairperson Joe Longo as the ‘biggest change to company

reporting in a generation’.[106]

The Coalition Senators argued that the Senate Economics Legislation Committee had

only a week to report on this significant change to Australia’s corporate law.[107]

Therefore, they recommended:

The Senate should extend the committee’s consideration of

this legislation, and additional hearings be scheduled to hear from a diverse

range of witnesses, including small business representatives, to contemplate

the impacts on supply chains, the regulatory burden, access to finance, and

competition.[108]

Group 3 entities

The Coalition Senators expressed concerns that ‘the Bill

places a disproportionate compliance burden on Group 3 entities, the vast

majority of whom do not have any material impact on the climate’.[109]

Under the proposed regime, entities in Group 3 are exempt

from climate-related financial disclosures if they can demonstrate that they

have no material climate-related risks or opportunities.[110]

The Coalition Senators argued entities can only assess

materiality after conducting an audit, which means ‘the vast majority of Group

3 businesses will be required to undertake a costly audit and seek external

assurances, all to find that they have nothing to report.’[111]

The Senators also asserted:

Group 3 entities are small and medium sized Australian

businesses, usually closely-held by family groups with few or no external

stakeholders. Critically, these businesses very rarely receive foreign capital.[112]

Consequently, the Senators recommended:

That Group 3 entities be removed entirely from the regime.

Alternatively, that the threshold for Group 3 entities be increased to $100

million in gross revenue or $50 million in gross assets. …

In the event that Group 3 entities remain covered by the

regime, those entities should be subject to simplified climate reporting

standards, similar to the simplified financial accounting standards that apply

to Tier 2 reporting entities. Critically, the requirement of an audit of a

statement of no material climate risks or opportunities should be removed.[113]

Ministerial direction

Under the proposed disclosure regime, the Minister may

make a legislative instrument to require additional statements and notes

relating to sustainability-related financial matters to be included as part of

an entity’s annual sustainability report.[114]

In their Dissenting Report, the Coalition Senators

expressed concerns that this gives the Minister:

… broad, unfettered discretion to require disclosure

of “financial matters concerning environmental sustainability” in an entity’s

sustainability report through legislative instrument.[115]

[emphasis added]

As such, the Senators recommended:

That the Minister’s proposed discretion in sections

296A(4)-(5) and 296(C) to require disclosure of “financial matters concerning

environmental sustainability” be removed, or subject to explicit requirements

of industry consultation.[116]

Modified liability

Coalition Senators acknowledged that the modified

liability approach gives group 1 entities three-year protection from litigation

concerning scope 3 disclosures, scenario analysis and transition plans.

However, the Senators said they remain concerned that more should be done to

prevent undue legal risk for companies.

The Senators noted:

The United States has taken a far more conservative approach.

Its modified liability is not time-bound, and it explicitly covers disclosures

regarding scenario analysis, transition planning, internal carbon pricing, and

targets and goals disclosures. US businesses also have the benefit of existing

safe harbour provisions for forward-looking statements, making litigation risk

far less than for Australian firms.[117]

The Coalition Senators argued that the protection scope of

Australia’s modified liability should be expanded, and they recommended:

That modified

liability protections be extended to statements replicating information in a

Sustainability Report or Audit Report in investor briefings, website

statements, public addresses, or other like documents, and that further

consideration be given to the appropriateness of compliance remaining with the

regulator for an extended period.[118]

Assurance requirements

Coalition Senators noted Schedule 4 inserts proposed

section 307AA to the Corporations Act, which will require a reasonable

level of assurance of all climate disclosures for corporate reporting periods

from 1 July 2030. The Senators recommended:

That the mandatory reasonable level assurance requirements of

section 307AA be removed and an assessment be done after four years to consider

what is possible and important to assure by early 2030.[119]

Australian Greens

Senator Nick McKim, of the Australian Greens, made

additional comments about the Bill. The Australian Greens asserted that the

proposed climate disclosure regime is ‘long overdue’, but also argued that

several aspects of the disclosure regime must be amended to ensure a long-term

framework that disincentivises greenwashing.[120]

The Greens said the modified liability is an ‘overreach’

to achieve the policy objectives of transitional arrangements:

The Bill is providing entities with a three year immunity

from civil actions over matters that relate to a company’s scope 3 emissions

reporting, future scenario planning or transition plans. …

While these three areas are novel for companies to report on,

and by their nature, inherently involve some uncertainty when first commencing,

the modified liability is an overreach in both scope and duration in order to

achieve the policy objectives of transitional arrangements.[121]

Furthermore, the Greens said Group 1 entities are typically the best prepared entities to

comply with the proposed mandatory disclosure regime. However, Group 1 entities

will receive the longest immunity period under modified liability. In contrast,

Group 3 entities, which are typically the least equipped, will be granted the

shortest immunity period.[122]

The Greens recommended:

The modified liability should be spread out amongst the three

groups to run for one, or at most two years from entry of that group so as not

disproportionately benefit the biggest companies at the expense of smaller

ones. ASIC should be given additional resources to prepare any necessary legal

proceedings during this modified liability period.[123]

As noted, some environmental advocacy groups argued that

the modified liability provisions should be completely removed.[124]

The Australian Greens do not advocate for the removal of modified

liability. Instead, the Greens said the compromise proposal submitted by Equity

Generation Lawyers to restrict the modified liability immunity to misleading

and deceptive conduct is a sensible proposal.[125]

As such, the Greens recommended:

The modified liability provisions be reduced so that they

only cover misleading and deceptive conduct seeking loss or damage.[126]

Financial implications

The Explanatory Memorandum notes that Schedule 4 fully

implements the ‘Mandating Climate-Related Financial Disclosure’ measure in the

2023–2024 MYEFO,[127]

which is estimated to decrease budget receipts by $24.7 million over the

forward estimates period (2024–25 to 2026–27).[128]

Commencement

Schedule 4 of the Bill commences on the day after Royal

Assent.[129]

As noted, the requirement to prepare a sustainability report will be

progressively phased in for different entities based on the size of the entity.

Schedules 1, 2, 3 and 5 – Financial Market

Infrastructure Regulatory Reforms

Background

What

are financial market infrastructures?

Schedules 1, 2, 3 and 5 to the Bill aim to

strengthen regulatory arrangements for Australia’s financial market infrastructures

(FMIs), particularly in relation to clearing and settlement facilities.[130]

FMIs are the systems and networks that enable the

execution, clearing, and settlement of financial transactions.[131]

Without these infrastructures, investors would not be able to conduct vast

volumes of financial transactions daily. FMIs encompass various systems and

networks, including payment systems, central counterparty clearing houses, and

securities settlement facilities.[132]

According to the Bank of England in this explanatory

video, FMIs are commonly referred to as ‘the plumbing of the financial

system’.[133]

This is because although most FMIs are hidden to the public, they are crucial

for the smooth operation of financial markets, similar to how water plumbing is

a hidden but crucial component of a home.

Drawing an analogy from transportation: well-maintained

transport infrastructures (roads, railways, airports) are vital for people to

travel safely and quickly. In the same vein, well‑maintained FMIs are

essential for investors to buy and sell financial products smoothly and

efficiently.

Some of Australia’s roads and railways are privately owned

and operated. Similarly, some of Australia’s FMIs are operated by companies

owned by private investors. For example, the Australian Securities Exchange

(ASX) Ltd, a publicly traded company with many private investors,[134]

is the dominant operator of clearing and settlement facilities for the

Australian share market.[135]

Government agencies are responsible for regulating vehicle

safety standards and updating traffic rules for the purpose of minimising

traffic accidents. Likewise, financial regulatory agencies – including the

Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and the Australian Securities and Investments

Commission (ASIC) – are responsible for overseeing Australia’s FMIs, including

those that are privately owned.[136]

The RBA is responsible for promoting safe and resilient FMIs,[137]

while ASIC is responsible for supervising the operators of FMIs.[138]

Regulatory oversight of ASX Ltd

As noted, ASX Ltd operates some of Australia’s key FMIs,

particularly clearing and settlement facilities. Consequently, ASX Ltd is

subject to regulatory oversight to ensure that these FMIs meet rigorous

standards of security and efficiency.

For example, any investor seeking to own more than 15% of voting

power (typically equivalent to share ownership) in ASX Ltd must obtain approval

via a regulation.[139]

Any such regulation

can be disallowed by a majority vote in either chamber of Parliament.

In 2010, a Singaporean company attempted to acquire over

15% of ASX Ltd, but this attempt was blocked by then-Treasurer Wayne Swan,

under foreign investment laws, on the grounds that the takeover was not in

Australia’s national interest.[140]

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation speculated

that even if Treasurer Swan gave approval to the foreign takeover, the

Parliament would not approve a change in regulations under the Corporations

Act to allow the deal to proceed.[141]

This reflected the importance of maintaining regulatory oversight over the

ownership of ASX Ltd due to its role as an operator of Australia’s FMIs,

particularly in relation to clearing and settlement facilities.

What

is clearing and settlement in finance?

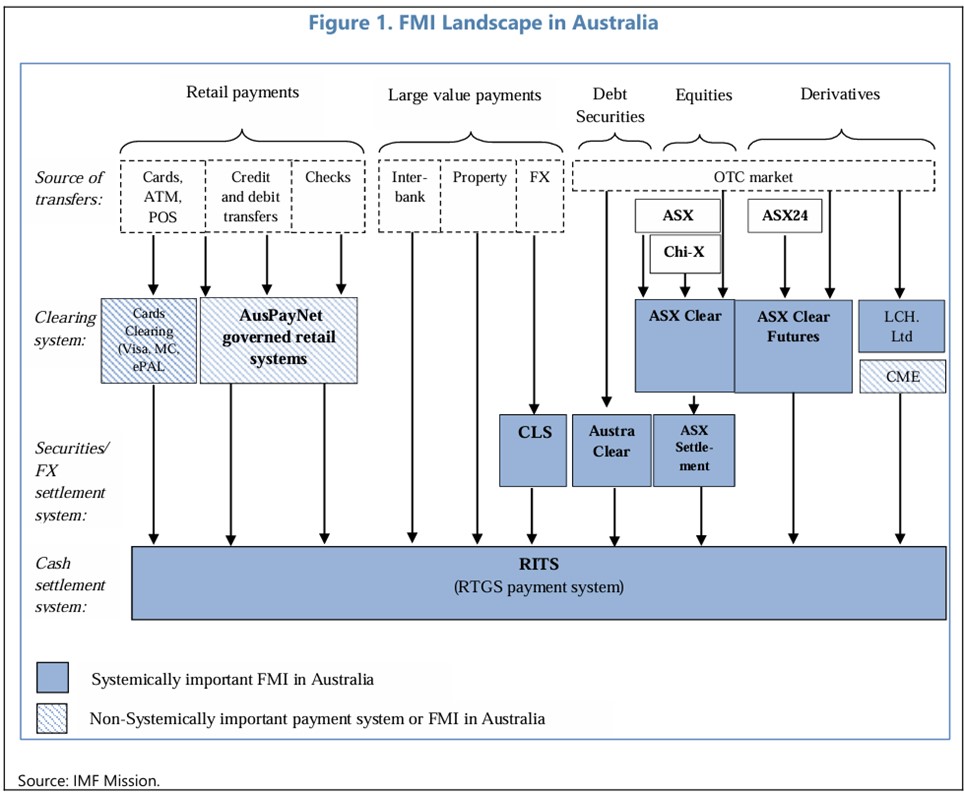

Figure 4 indicates that clearing and settlement (CS)

facilities are ‘systematically important FMIs’ in Australia.[142]

The Council of Financial Regulators (CFR), a coordinating organisation for Australia’s

financial regulatory agencies, highlights how crucial CS facilities are to the

smooth operation of Australia’s financial markets:

FMIs support transactions in securities with a total annual

value of $16 trillion and derivatives with a total annual value of $185

trillion. These markets turn over value equivalent to Australia's annual GDP

every three business days. Without clearing and settlement facilities, and

access to financial benchmarks, many financial markets could not operate.[143]

[emphasis added]

Figure 4: FMI landscape in Australia

Source: International

Monetary Fund (IMF), ‘IMF Financial Sector Assessment Program, 2019 Technical

Note – Supervision, Oversight and Resolution Planning of Financial Market

Infrastructures’, 11.

Drawing an analogy from real estate: investor Ian has

successfully bid for a house at auction. A crucial step in the purchase process

is for Ian to pay the seller and ‘settle’ the transaction. This means Ian may

need to hire conveyancing lawyers to handle the property settlement process and

ensure that the housing title is transferred to his name.

Turning to the financial industry, Ian has purchased some

company shares on the ASX trading platform. A crucial step in the purchase

process is for Ian to ‘settle’ the financial transaction with the seller. In

other words, the transaction must be effected through CS facilities to confirm

Ian as the new owner of the shares.

ASX Ltd – through its subsidiaries ASX

Clear and ASX

Settlement – is the sole provider of clearing and settlement

services for Australia’s cash equity market.[144]

This means Ian has to pay brokerage fees to receive clearing and settlement

services from ASX.[145]

If

the CS facilities owned and operated by ASX experience a system outage or

congestion, then Ian and millions of other investors would not be able to

purchase and sell equities. As noted, FMIs enable millions of financial

transactions to occur daily, and disruption to this traffic could cause

immeasurable harm to the Australian economy.

In 2019, the Council of Financial Regulators warned that a

vast number of financial transactions in Australia are centrally cleared and

settled (mostly through CS facilities operated by ASX), and this has:

… led to a concentration of risks in the clearing and

settlement facilities themselves.

Disruption at an FMI or the failure of its operations would

prevent some or all of the usual activity that it facilitated taking place,

severely undermining the operation of the financial system… The CFR is

proposing a broad package of reforms to improve the regulation of FMIs in

Australia.[146]

ASX

system outage on 16 November 2020

Just as roads can deteriorate and become congested over

time, FMIs can also age and grow increasingly susceptible to crises. On 16

November 2020, the ASX trading platform experienced a system outage triggered

by a software glitch. The problem prompted ASX to pause stock trading at 10:24am,

and trading did not resume for the remainder of the day.[147]

Some investors suffered financial losses due to the outage and demanded

compensation.[148]

Following the outage on 16 November 2020, ASX Ltd commissioned

IBM Australia Ltd to undertake an independent review of the ASX Trade Refresh

project.[149]

The review found that the CS facilities operated by ASX did not directly cause

the outage. However, the review also identified several key shortcomings in the

ASX governance processes that could affect the efficiency of CS facilities if

not addressed.[150]

The RBA concluded that:

While the CS facilities were not responsible for the

incidents affecting ASX trading systems, ASX applies a group-wide approach to

operational risk and project management, so there is a risk that the

shortcomings identified by IBM in the ASX Trade Refresh project could affect

the CS facilities if not addressed.

Accordingly, the Bank will work closely with ASIC and ASX to

ensure that any relevant findings or recommendations from the IBM review are

applied to its clearing and settlement operations, and in particular to the

CHESS replacement program.[151]

[emphasis added]

ASX

failure to replace its decades-old CHESS system

ASX Ltd is a licensed operator of CS facilities in

Australia.[152]

As noted, it maintains a monopoly over some of Australia’s FMIs,

including the CHESS

system, which handles the clearing and settlement of stock trading

conducted through ASX.[153]

The CHESS system, or the Clearing House Electronic

Subregister System, is a crucial FMI that enables financial transactions to be

cleared and settled.[154]

ASX relies on the CHESS system to act as a ‘middleman’ (known as a central

counterparty) between investors, and to maintain its monopoly over the

provision of clearing and settlement services for Australia’s share market.

The ASX’s monopolistic position has come under heavy

criticism in recent years, particularly in the wake of its system outage and

subsequent failure to replace its decades-old CHESS system.[155]

The CHESS system was developed and has been operational since the early 1990s. As

the technology on which CHESS has been built is three-decades old, it struggles

to efficiently support the increasing scale and complexity of modern financial

markets.[156]

In 2016, ASX enlisted an American startup company to build

a blockchain replacement for CHESS. However, after years of delays and

setbacks, in November 2022 ASX announced that its CHESS replacement project

had failed to meet expectations.[157]

The ASX failure to replace the CHESS system has

highlighted regulatory gaps in the supervision of financial market infrastructures.

As noted, the RBA is responsible for promoting resilient FMIs to support

financial stability.[158]

The Australian

Financial Review reported that:

ASX’s monopoly on clearing and settling cash equity market

trades is under threat amid political and investor fury over the exchange’s

failure to deliver a critical project to update the technology underpinning the

sharemarket.

… Queensland Liberal Senator Paul Scarr put the heat back

on the regulators [ASIC and RBA], suggesting they consider whether ASX’s

control of the critical national infrastructure creates a conflict of interest

that should force a change to market structure. [159]

[emphasis added]

Furthermore, the Australian

Financial Review argued:

ASX tech disaster exposes regulatory holes. It is time for

Treasurer Jim Chalmers to take a keen interest in the country’s financial

market infrastructure and review the clearing and settlement processes as well

as its supervision.[160]

The

Government’s commitment to improve regulatory arrangements for FMIs

On 14 December 2022, Treasurer Jim Chalmers issued a media

statement announcing the Albanese Government’s commitment to undertake

reforms aimed at enhancing Australia’s financial system. To that end, the

Government would act on recommendations by the Council of Financial Regulators

(CFR) to improve regulatory arrangements for Australia’s FMIs.[161]

In its Financial

Market Infrastructure Regulatory Reforms – Advice

to Government from the Council of Financial Regulators report

released in July 2020, the CFR identified several regulatory gaps in relation

to FMIs. Specifically, the CFR pointed out:

- Financial regulatory agencies (specifically, ASIC and RBA) do not

have crisis management powers to resolve a distressed clearing and settlement

facility.

- The distribution of powers between the Minister, ASIC, and the

RBA does not correspond to their legislative mandates or international best

practice.

- The regulators do not have sufficient supervisory or enforcement

powers to most effectively monitor or manage the risks posed by FMIs to the

orderly provision of services and financial stability.[162]

The CFR made several recommendations to address these

regulatory gaps.[163]

The CFR recommendations build on the findings of earlier government reports and

international reviews, including the 2014

Financial System Inquiry (also known as ‘The Murray Inquiry’) and the IMF’s

2019 Financial Sector Assessment Program review.[164]

Key

issues and provisions

Schedules 1, 2 and 3 of the Bill implement the

recommendations contained in the CFR’s Financial

Market Infrastructure Regulatory Reforms report by:

- introducing

a crisis management and resolution regime through the amendments in Schedule 1

- strengthening ASIC and the RBA’s licensing, supervisory and

enforcement powers through the amendments in Schedule 2

- making changes to and adjusting roles and responsibilities

between the Minister, ASIC and the RBA through the amendments in Schedule 3.[165]

Schedule 5 makes related minor and technical amendments to

Commonwealth legislation to enable the implementation of the recommendations.[166]

Establishment

of a crisis resolution regime for distressed FMIs

Schedule 1 amends the Corporations Act to establish

a crisis resolution regime for distressed FMIs. The proposed crisis resolution

regime empowers the RBA to step in and take actions when a CS facility is in

distress or facing an imminent crisis.[167]

In other words, the crisis resolution regime would give RBA the tools it needs

to support the continued operation of distressed CS facilities considering

their critical market functions.

To that end, the Bill inserts proposed sections 830B

and 832A to the Corporations Act to empower the RBA to appoint a statutory

manager to take control of a CS facility that is experiencing significant

distress or crisis.[168]

This new power is known as ‘statutory management’ and is a part of the crisis

resolution regime established to handle situations where a CS facility fails or

is at risk of failing, which could impact financial stability.

Specifically, the proposed sections give the statutory

manager powers to take over the management of the CS facility, replacing the

board of directors, and managing the operations of the facility to ensure the

stability of the broader financial system. The statutory manager can make

decisions about the operations, management, and the strategic direction of the

facility during the crisis period.[169]

The Bill also inserts proposed section 835B to give

a new ‘directions power’ to the RBA.[170]

This means the RBA can direct statutory managers to take specific actions

concerning the affairs of a CS facility.[171]

The Treasurer, with the written approval of the Finance

Minister, is permitted to activate a maximum appropriation of up to $5 billion

in a CS facility crisis event. This appropriation is designated to support the

essential operations of domestic clearing and settlement facilities during a

crisis.[172]

The Australian

Financial Review commented this $5 billion appropriation mechanism will

‘only be used in the most extreme instances of market crisis’.[173]

While the Bill gives the RBA the power to appoint a

statutory manager to step in and take control of distressed CS facilities, it

also empowers the RBA to take preventative measures that can help avoid them occurring

in the first place.

To that end, provisions in Schedules 1 and 2 introduce a

suite of general powers for the RBA, including imposing notification

requirements, issuing directives, engaging in resolution planning, and setting

resolvability standards.[174]

In particular, proposed section 821BA (at item

26 of Schedule 1) empowers the RBA to impose notification

obligations on a CS facility operator: CS facility licensees are obligated to

notify the RBA of material changes that could lead to distress, thereby

increasing the RBA’s ability to mitigate the risk of crises materialising.

Failure to comply is an offence.

Enhanced

supervisory and licensing powers

As noted, CS facilities are essential to the smooth

functioning of Australia’s financial markets. Given their importance, CS

facilities must be licensed under the Corporations Act, which mandates

that these facilities must have appropriate operational rules and procedures to

ensure they function in a fair and effective manner.[175]

Once licensed, the CS facility licensees are subject to

the continuous oversight of both the RBA and ASIC. The RBA is tasked with annual

compliance assessment of each licensed facility against established Financial

Stability Standards, while ASIC ensures compliance with other supervisory

responsibilities.[176]

At the time of writing, there are 7 licensed CS facilities

operating in Australia, 3 of which are subsidiaries of ASX Ltd.[177]

Nevertheless, since 2011, ASX Ltd has faced some competition from overseas CS

facility licensees operating in Australia.[178]

Provisions in Schedules 2 and 3 provide ASIC with enhanced

supervisory and licensing powers to regulate CS facility licensees. Details of

ASIC’s new powers are specified in pages 92 to 95 of the Explanatory Memorandum.

Transfer of certain

ministerial powers to regulators

Currently the Minister has responsibility for a number of

operational decisions in relation to licensing and supervision of CS facility

operators. The Bill includes provisions to transfer certain ministerial powers

to regulators to streamline the regulation of FMIs.[179]

This implements recommendation 2 of the CFR’s Financial

Market Infrastructure Regulatory Reforms report. Specifically, the CFR

argued that the rationale for the transfer of ministerial powers is:

Effective regulation relies on a clear separation of

responsibilities between the Government and regulators, with the Government

responsible for making and reviewing laws and independent regulators empowered

to apply those laws in an objective and impartial manner. The current

arrangements, where the Minister has responsibility for a number of operational

decisions in relation to licensing and supervision of market operators and

clearing and settlement facility operators, is inconsistent with this approach and

out of step with comparable international regimes.[180]

Details of ASIC’s new powers are specified in pages 89 to

92 of the Explanatory

Memorandum.

Transfer of power to the Minister to approve increases in

voting power

As noted, ASX Ltd is subject to a 15% ownership limitation

under the Corporations Act.[181]

This means any investor seeking to own more than 15% of ASX Ltd must obtain

approval by regulation. Any such regulation would be subject to disallowance

by Parliament.

Schedule 2 amends the Corporations Act to:

- provide that the Minister’s approval is only required when an

investor seeks to own more than 20% (rather than 15%) of ASX Ltd[182]

- remove the requirement for approval by regulation; in other

words, the Minister (Treasurer) would have ‘total discretion’ to approve or

reject the approval.[183]

The repeal of subsection 850B(2) implements a

recommendation of the CFR.[184]

The Coalition and the Australian Greens oppose this amendment (see the ‘Policy

position of non-government parties’ section).

Policy position of

non-government parties/independents

Coalition

In their Dissenting Report on the Bill, the Coalition

Senators raised concerns about the amendment to section 850B of the Corporations

Act.

Currently any investor seeking to own more than 15% of ASX

Ltd must obtain approval via regulation. The amendment would remove the

requirement for increases in voting power above 15% to be approved through

regulation. Coalition Senators are concerned the Treasurer would have ‘total

discretion’ to approve or reject such increases, a decision that would not be subject

to disallowance.[185]

The Coalition Senators said they are of the view that the

Parliament should retain some scrutiny over these approvals concerning ASX

ownership, instead of leaving it entirely to the Minister of the day.[186]

Consequently, the Senators recommended:

That the Bill be amended to retain the requirement for

regulations to be made for the purpose of subsection 850B(1)(c) of the Corporations

Act 2001, and to retain their disallowability under subsection 850B(2).[187]

Australian Greens

The Australian Greens argued: ‘the ASX is public

infrastructure that—like much of Australia public infrastructure and

institutions—should never have been privatised’.[188]

ASX was formed in 1987 after the Australian Parliament

passed legislation enabling the amalgamation of six independent state-based

stock exchanges.[189]

Although ASX was not a government-owned organisation at the time, it was a mutual

organisation owned by Australian stockbrokers.[190]

In 1998, ASX was demutualised and became a publicly traded

company.[191]

This transition enabled any individual or organisation (foreign or domestic) to

buy shares and gain partial ownership of ASX Ltd.

Considering the ASX’s dominant role in the Australian financial

markets, some commentators have argued that the Australian Government, rather

than private individuals or foreign companies, should have greater oversight of

ASX operation to better protect public interests.[192]

The Australian Greens criticised the proposal to weaken ministerial

approval powers over ownership of ASX.[193]

If the Bill is passed, investors would only need the Treasurer’s approval when

seeking to own more than 20% of voting power in ASX.

Consequently, the Greens recommended:

In the absence of any compelling justification from the

Government, Part 4 of Schedule 2 that lifts the ownership threshold from 15% to

20% voting power in ASX Limited in order to require Ministerial approval should

be removed from the Bill.[194]

Position

of major interest groups

In December 2023, the Treasury conducted a consultation process

and sought stakeholder feedback regarding FMI regulatory reforms. Fifteen

stakeholders made written submissions, and the Senate Economics Legislation

Committee noted the ‘overwhelmingly positive support’ from stakeholders for the

proposed FMI reforms.[195]

ASX Ltd

ASX Ltd is the dominant operator of CS facilities in

Australia. As such, changes in the regulation of FMIs, especially those that

impact licensing and crisis management protocols, could significantly affect ASX’s

interests.

While ASX is broadly supportive of

the reform measures to increase the resilience of the financial system,[196]

it has expressed concerns regarding specific provisions of the Bill. For

example, the Bill empowers the RBA to appoint a statutory manager to take

control of a CS facility that is experiencing significant distress or crisis. ASX

expresses concerns about the broad powers given to a statutory manager:

ASX considers that certain powers proposed in the draft

legislation go beyond what is necessary to allow the statutory

manager to efficiently carry out their functions and powers in resolving a CS

facility or are unnecessary in light of other provisions in the exposure draft

legislation. With the principles of proportionality and necessity in mind, ASX

submits that certain powers of the statutory manager should be removed or

limited, including the powers to amend a body corporate’s constitution and

information gathering powers.[197]

[emphasis added]

ASX suggests that a statutory manager’s powers should not

impede the essential operational activities of the CS facilities.

Furthermore, ASX has expressed concerns that potential

abuse of the RBA’s new powers, especially in transferring ownership or taking control

of a CS facility during a crisis, could undermine the fair value of assets for

asset holders:

Given the breadth and seriousness of the proposed powers, it

is also appropriate that the resolution powers are balanced with adequate

protections for asset holders. ... ASX considers protections for asset holders

should not impede the timely transfer of the shares or business of the [CS] facility

when necessary in a crisis situation. Rather, these protections should ensure

that the decision is only taken as a last resort, that there is an appropriate

level of transparency regarding the fair value of the assets via an expert

report and that compensation is available to asset holders for any difference

between the value realised under a transfer determination and the fair value of

the assets.[198]

These concerns reflect ASX’s acknowledgement that while

statutory management powers are necessary for crisis resolution, they must be

executed in a way that does not compromise the rights of licenced CS facility

operators.

Cboe Australia

Cboe Australia is a rival share trading exchange to ASX

Ltd.[199]

As noted, currently ASX is a monopolistic provider of clearing and

settlement services for Australia’s share market. At the same time, ASX

provides Cboe non‑discriminatory access to its CS facilities through

commercial arrangements (known as ‘Trade

Acceptance Service’).[200]

This means Cboe is not a licensed operator of CS facilities; rather, Cboe pays

service fees to ASX in order to access the latter’s CS facilities. The Australian

Financial Review speculated that ‘Cboe plots ambitious plan to erode

ASX dominance’ in the provision of clearing and settlement services.[201]

Cboe is generally supportive of the FMI reforms, and it

has articulated its policy position with a particular focus on enhancing

competition within the financial sector:

[Cboe] is strongly of the view that a lack of competition was

a critical factor in the negative outcomes of the initial CHESS replacement

project, where the monopoly clearing provider’s failed technology migration

cost the financial industry several hundred million dollars’ worth of wasted

output. The failed replacement project continues to have a negative impact on

Australian investors, participants, markets, and the broader financial system,

while the Australian clearing environment continues to be characterised by high

fees, a lack of product innovation, and outdated infrastructure.[202]

Put simply, Cboe argues ASX’s monopoly in the provision of

clearing and settlement services has led to outdated infrastructure, and that these

issues could have been mitigated with a more competitive environment. As such, Cboe

strongly advocates for several specific regulatory changes that support

competition, suggesting that such measures are essential for preventing

monopolistic practices and improving the overall health of the financial market

infrastructure.[203]

CME

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) is incorporated in

the United States and operates in Australia under an overseas CS facility

licence.[204]

This allows the CME to provide clearing and settlement services in the

Australian financial markets to complement its global operations in derivatives

trading and other financial products.

Since 2011, ASX has faced competition from overseas CS

facility licensees in some financial markets, including competition from CME

for over-the-counter derivatives clearing services.[205]

In its written submission to the Treasury, the CME emphasises

the importance of mutual deference for effective cross-border operations

of FMIs.[206]

Mutual deference in the context of FMI regulation refers to the principle

whereby regulators in one jurisdiction recognise and respect the regulatory

frameworks of another jurisdiction. Mutual deference is especially important

for corporations that operate across borders, as it helps to reduce regulatory

duplication and conflicts.

Put simply, the CME argues that certain provisions in the

Bill should be amended to explicitly exclude overseas CS facility licensees

from domestic crisis management powers unless requested by regulators in

foreign countries (in this case, the US).

Financial

implications

Schedules 1, 2, 3 and 5 are estimated to have no cost to

Government over the forward estimates period.[207]

Commencement

The amendments that establish the FMI crisis resolution

powers and the crisis prevention powers in Schedule 1 and Part 9 of Schedule 2

of the Bill commence on the seventh day after Royal Assent.[208]

For Schedule 2 of the Bill:

Schedule 3 of the Bill commences 7 days after Royal

Assent.

Schedule 5 to the Bill commences on the day after Royal

Assent.[209]