December 2011 marks the centenary of the first national art collection established by the Commonwealth of Australia—the Historic Memorials Collection (HMC). The establishment of this collection in 1911 also set in place the foundations for other important collecting institutions such as the National Gallery of Australia, and the National Portrait Gallery.

Today I intend to outline a brief history of the establishment of the collection, and then examine a selection of portraits from the collection, including some that are rarely seen publicly, and are currently being exhibited here at Parliament House to celebrate this centenary.

The story of the HMC is also a story about the intersection of art and politics and the importance of this connection was never more evident than in the period leading up to the establishment of the collection in 1911. One hundred years ago Australia was still very much a new nation, and to properly understand the origins of the HMC, we need to look back on the preceding decades, particularly the period leading up to federation in 1901.

The federation movement was marked by dissent and the competing priorities and interests of the separate colonies, but had arisen out of a growing sense of idealised national identity in the late 19th century. One of its key proponents, the future prime minister Alfred Deakin, said that federation ‘must always appear to have been secured by a series of miracles’.[1]

Australian constitutional historian Helen Irving has written convincingly about how the people of the states first had to imagine the idea of a nation called Australia, before that nation could exist.[2] That process of imagining the country into existence occurred at a number of levels.

The drafters of the Australian Constitution—lawyers and politicians—built support for their cause on a sense of common identity that was very much about promoting allegiance to a vision of a dominant, white, British culture; and convincing their constituents that in uniting the colonies, the freedom and economic security of the new nation would be assured. With the benefit of hindsight we can say they seem largely to have gotten it right. However, as we know, politicians promising a brighter future will not necessarily automatically win public support.

I want to quickly divert here to reflect on two names that keep recurring when examining the origins of the HMC—on the political side, Alfred Deakin, and on the artistic side, Tom Roberts. The possible points of connections between these two men, and to a lesser extent some of the other major players who were their colleagues in art and politics during this period, are intriguing. On the surface, Roberts and Deakin appear to have quite a lot in common. Deakin was born in 1856 in Collingwood, Melbourne. Roberts was also born in 1856, in Dorset, England, and came to live in Collingwood, Melbourne at age 13. Both men liked to read and write, and moved in literary and artistic circles. Deakin also became engaged with spiritualism and philosophy. Both became leaders in their fields, acting as teachers and mentors to others in their circle, and worked hard to promote causes that they passionately believed in.

Deakin’s biographer, J.A. La Nauze, suggests that Roberts and Deakin probably first met in 1901,[3] while Roberts was working on his Big Picture (I will talk more about that painting later), but I find it tempting to speculate that they could have met earlier. Melbourne was certainly a much smaller place then that it is now. I haven’t found any historical references suggesting that they met often, but they definitely corresponded regularly, over a period of more than ten years. La Nauze notes that their letters indicate a friendly informality, and suggest that they each regarded the other as an intellectual peer. By far the most striking thing that they shared in common was an enthusiasm for documenting and reporting the characters and events of their time. Deakin wrote extensively throughout his life keeping diaries and notebooks. His writings about the federation movement, including character studies of many of the leading figures of that time, provide insight into the processes that were at work. Roberts, through his painting, also attempted to capture some of the history of the evolution of the nation, and his portrait character studies similarly attempted to capture a record of ‘types’[4] (e.g. his Church, State and Law triptych).

But returning again to Helen Irving’s theme of imagining the nation—the efforts of the federationists in capturing the public imagination were substantially assisted by the creative and sporting elements of society. Irving writes about the flowering of distinctively nationalist literature, poetry and music, as well as a distinctive sporting culture. Visual arts also played a vital role—and none more so than the members of what we now know as the Heidelberg group of artists (also known as the Australian Impressionists).

Irving notes that:

the movements for political and cultural nationalism were, inevitably, in advance of popular demand. They were led at the start by a small elite circle whose quest was to forge a distinctive Australian national character out of diffuse British references and leanings.[5]

Irving doesn’t name the members of this elite circle—but I am reasonably confident she might include Alfred Deakin and Tom Roberts as part of their number.

In 1894, Roberts’ colleague, the artist Arthur Streeton, wrote in a federalist journal Commonwealth that it seemed ‘as though Federation were unconsciously begun by the artists and national galleries’.[6]

Certainly, Roberts and his peers articulated a new representation of Australian landscape and people through some of their key works of the 1880s and 1890s. While undoubtedly influenced by European art trends in impressionism, theirs was a different kind of work. Through their conscious depiction of harsh, hot sunlight, bleached colours, and uniquely sparse and spindly Australian vegetation, they purposefully set out to create a new, uniquely Australian style of art. We can see this exemplified in paintings such as Near Heidelberg, painted by Arthur Streeton in 1890, and Charles Conder’s Summer Idyll of 1889.

Likewise, they celebrated the value of a characteristically Australian form of human endeavour, and helped mythologise the notion of the Australian bush character, shaped by the hardships that faced those who settled in it—for example, Down on his Luck by Frederick McCubbin in 1889, and A Break Away! painted by Roberts in 1891.

Eventually, the grand vision of the federal movement was realised, and the new nation of Australia came into existence on 1 January 1901 in Centennial Park, Sydney, amid great ceremony and celebration.

The enthusiasm of the January celebrations in Sydney, were echoed in Melbourne in May, when the first Parliament was opened by the Duke of Cornwall and York. Tom Roberts captured this moment in his epic history painting, colloquially known as the ‘Big Picture’, which hangs just outside this room where I am speaking today. The Big Picture is not formally part of the HMC; however, I believe that this painting, and its creator Tom Roberts, are such critical components of the story of establishment of the HMC, that they deserve special mention.

|

Opening of the First Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia by HRH The Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V), 9 May 1901, 1903 by Tom Roberts (1856–1931). Courtesy of Parliament House Art Collection Canberra, ACT.

|

The painting was commissioned by a group of Melbourne businessmen who intended it as a gift to the new king, Edward VII. Roberts was not the first artist commissioned but when the first choice, J.C. Waites, backed out, Roberts stepped in. Roberts had to undertake a minimum of 250 individual portraits (eventually it amounted to 269 named individuals). It took him over two years to complete the work, required extensive travel in Australia and England, and resulted in a monumental canvas—at just over five metres by three metres.

He completed the painting in 1904, whereupon it was presented to the King, and it remained in England, in St James Palace, until 1958. The painting was eventually returned to Australia following persistent lobbying from a number of parliamentary figures, and is now on permanent loan to the Australian Parliament from the Royal Collection.

The painting has received mixed reviews over time—it certainly lacks the vitality and liveliness that is so engaging in some of Roberts’ individual portraits. It is also often cited as the catalyst for Roberts entering a dark period in his artistic career. Roberts himself wrote in letters to his friends about the effort it cost him to complete the work; however, he equally regarded it as something of a personal mission to record what he saw as a momentous occasion. Personally, I think it has been unfairly judged. True, it is a darker and more sombre work than most of Roberts’ other paintings, but he was accurately depicting the state of mourning of the guests attending the function.[7] Its scale, and the volume of detail it contains, are such that it requires close study to be properly appreciated. Certainly it demonstrates technical mastery in maintaining accurate proportion, scale and perspective across such a vast group of figures.

Interestingly, both Tom Roberts and Frederick McCubbin were invited guests at the opening event—possibly in recognition of their role in shaping the public imagination of the new nation—probably an indication of their continuing association with politics, and their prominence in Melbourne society as artists.

Moving forward, politicians got on with the business of governing, and the leading artists of the day attempted to consolidate their successes and pursue new artistic fields. Many of Australia’s leading artists headed to Europe to try their fortune, with varying degrees of success.

In the decade from 1901 to 1911 Australia had five different prime ministers (with Alfred Deakin serving three separate terms of office and Andrew Fisher serving two terms). Parliament passed the Immigration Restriction Act, Australian troops were sent to the Boer War, the High Court was established, the world’s first feature film The Story of the Kelly Gang was made, and the US Navy’s ‘Great White Fleet’ visited Australia.

Throughout that decade, the topic of appropriate recognition of the people and events associated with the formation of the Commonwealth was periodically discussed in the new Parliament.

One of the primary advocates for some form of commemoration was artist Tom Roberts. Self-interest may have been part of his motivation, but no doubt his sincere belief in the importance of creating records for posterity, as demonstrated by his effort in completing the Big Picture, was also a factor.

Roberts wrote to Alfred Deakin in March 1910, ‘let me ask you to consider the importance of acting early … and let these records be painted … to give faithful representations of the first leaders of the Commonwealth’, further noting that:

it disturbs me to think that most of you are likely to go on till the inevitable comes, and leave behind nothing that will give the future anything that will show what you all were as men to look at.[8]

Deakin subsequently sent a copy of Roberts’ letter to Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, who told the Parliament in October 1911 that the government hoped to preserve ‘likenesses of the prominent statesmen of Australia’.[9] Two months later the Historic Memorials Committee was established as a ‘committee of consultation and advice in reference to the expenditure of votes for the Historic Memorials of Representative Men’[10], and the government allocated 500 pounds to commence this work.

I should comment here on the very specific gender reference—it is accurate, in that the HMC is very much a collection about men. Almost all the portrait subjects are male and almost all the artists commissioned to complete portraits have been male.

The committee consisted of the Prime Minister (as chair) as well as the President of the Senate, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Vice-President of the Executive Council, Leader of the Opposition, and the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate. (The make-up of the committee is still the same in 2011.) One of their early actions was to agree on a list of eminent men whose portraits should be painted, with the first portrait to be that of Sir Henry Parkes, who had died before the Constitution took effect. They also recognised a need for specialist expertise, and quickly established the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board (CAAB), to provide advice on the selection of suitable artists and to assess the quality of completed portraits.

The establishment of the committee and collection attracted considerable public attention and was not without controversy.

The Sydney Morning Herald, in September 1909 (Deakin was Prime Minister at that time, and Fisher was Leader of the Opposition) reported that:

Mr Deakin is to be congratulated on his decision to … make some provision for a gallery of national portraits. The form of words used by the Prime Minister in announcing his readiness to take this step, however, suggests a doubt as to whether he has in mind memorials to other than the political leaders of the Federal movement.[11]

In August 1912, the Brisbane Courier took up a similar argument (by now it was Fisher’s turn again to be prime minister):

|

The Hon. Alfred Deakin, 1914 by Frederick

McCubbin (1855–1917). Courtesy of Parliament House Art Collection Canberra, ACT.

|

Some men are born to greatness; others have it thrust upon them—and others thrust it upon themselves. The Historic Memorials Committee, of which the Federal Prime Minister is chairman, has approved of a report of an Art Advisory Board in connection with the perpetuation of the memories of Australia’s great men… Some of the names in the list are quite correctly included, but quite a number have no claim yet to be classed with the Immortals … Many of the really great names are ignored. In vain one looks for something to suggest remembrance of great explorers, poets, or authors. They are ignored so that the politicians, big and little, may be glorified.[12]

At this point, I will shift from considering the general history of the HMC, to examine a selection of portraits from the collection.

First, the portrait of Alfred Deakin by Frederick McCubbin. Perhaps the most surprising thing about this portrait is that it was not painted by Tom Roberts, given their apparent friendship and shared idealism. Roberts would seem to have been the obvious choice for the commission—but he was by then still living in England, and there had been some controversy about the HMC using artists based in England rather than granting commissions to artists living in Australia.

The Australian Dictionary of Biography entry for Deakin describes him as a memoirist, barrister, federationist, irrigationist, journalist, newspaper editor, land speculator, politician, and spiritualist.[13] He was known as a skilled orator and is often credited for helping popularise the federation cause. Deakin took a great interest in promoting arts and literature. He became Australia’s second prime minister in 1903, and served again as prime minister twice more. However, his political career apparently took a heavy toll and affected his health. By the time this portrait was painted, he was unwell, and possibly suffering the early stages of dementia. He died in 1919.

|

|

McCubbin was an Australian-born artist (also of Melbourne origin) who worked closely with Tom Roberts, Arthur Streeton and Charles Conder in the 1880s and 1890s. In the early 1900s he was at the height of his artistic powers and excelled as a landscape painter, but also painted figures. The portrait of Deakin is McCubbin’s only inclusion in the HMC, and is currently on display at the National Portrait Gallery, in an exhibition celebrating the centenary, with three other early HMC portraits—the portrait of Andrew Fisher by Emanuel Phillips Fox, Henry Parkes by Julian Ashton, and the remarkable portrait of King Edward VII by George Lambert. I would encourage you all to take time to look at these portraits while they are there.

Time does not allow a comprehensive review of the collection, so I will instead focus on some of the more significant portrait artists, and some of the ‘stand-out’ portraits in the collection.

Sir William Dargie (1912–2003) is an outstanding figure in Australian portraiture with a career that started in the 1930s and continued through most of the 20th century. Dargie is perhaps best known for his portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, painted in 1954. The painting was not commissioned by the Commonwealth, but was presented as a gift for the Historic Memorials Collection. Dargie won the Archibald Prize eight times between 1941 and 1956, and was an official war artist during World War II. Dargie painted in a style known as ‘tonal realism’ and was substantially influenced by Max Meldrum, and A.D. Colquhoun (both artists also represented in the HMC). He also played an important role in art administration and education, serving on many boards and councils. Most notably, he served as a long-term member (and eventually chair) of the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board (which advised the HMC) during the 1950s and 60s, when it played an important role in acquiring artworks for the national collection (most now held in the National Gallery collection).

|

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 1954 by Sir William Dargie (1912–2003). Courtesy of Parliament House Art Collection Canberra, ACT.

|

In total, Dargie completed eleven portraits for the Historic Memorials Collection (a number that seems unlikely to ever be eclipsed). His HMC subjects include Prime Ministers Arthur Fadden and John McEwen, Dame Enid Lyons, and Governors-General Sir William Slim and Lord Casey, as well as the famous and much loved painting of Queen Elizabeth II.

Bryan Westwood (1930–2000) has eight portraits in the HMC, and was twice a winner of the Archibald Prize. He was largely self-taught, and did not start painting until he was well into his 30s. He travelled extensively, and spent periods living in Europe and America. His work is usually described as ‘photo-realist’ and he painted very finely detailed, meticulously realistic portraits. In teaching himself how to paint, he studied the work of ‘old masters’, particularly Velazquez. One of the things I find particularly engaging about Westwood’s portraits, is that he was one of the first HMC portraitists to encompass a more personal dimension to the portraits—sometimes by including objects with specific personal associations, or by posing his subjects in more reflective and individual ways. See for example his beautifully painted portrait of Sir Magnus Cormack, former President of the Senate, painted in 1973, and Sir Anthony Mason, former Chief Justice, painted in 1992.

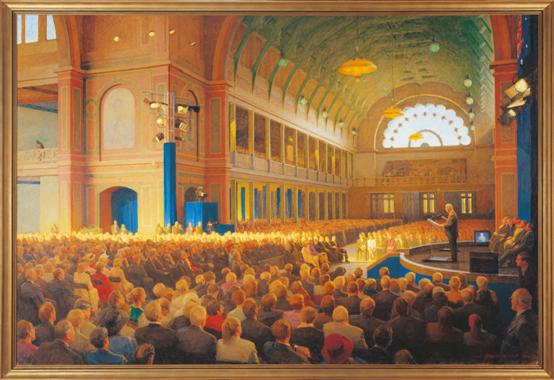

Robert Hannaford (born 1944) has completed nine commissions for the HMC, including a major work in 2001, depicting the centenary sitting of Parliament in the Melbourne Exhibition Building—an homage to Tom Roberts’, and displayed alongside the Big Picture, in Parliament House. Hannaford’s HMC portraits include Prime Minister Paul Keating, painted in 1997, and Governor-General Sir William Deane, painted in 2001. Unlike many other recent HMC portrait artists, Hannaford paints primarily from life, usually requiring his subjects to make themselves available for a week or more for portrait sittings—no easy feat if they are still in office.

|

Centenary of Federation Commemorative Sitting of Federal Parliament, Royal Exhibition Building, Melbourne, 9 May 2001, 2003 by Robert Hannaford (1944–). Courtesy of Parliament House Art Collection Canberra, ACT.

|

HMC portraits have occasionally been entered in the Archibald Prize, and at least three times have been winners. These three portraits, representing very different periods, and different styles of portraiture are: Max Meldrum’s 1939 winning portrait of Speaker George Bell, Joshua Smith’s 1944 winning portrait of Speaker John Rosevear, and Clifton Pugh’s 1972 winning portrait of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam. The Whitlam portrait was not commissioned for the HMC, but purchased at the suggestion of Mr Whitlam himself. Interestingly, it is probably one of the least realist portraits in the collection.

As mentioned previously, women are very much in the minority in the HMC, both as subjects and artists. However, they do appear from time to time. The first two portraits depicting women were William Dargie’s portrait of Enid Lyons from 1951, and Archie Colquhoun’s portrait of Senator Dorothy Tangney from 1946, commemorating their respective status as the first female member, and the first female senator in the Australian Parliament. Some of the significant women artists represented in the collection include Judy Cassab, who painted portraits of Speaker James Cope in 1973, and Chief Justice Sir Harry Gibbs in 1992. June Mendoza painted a distinctively informal portrait of Prime Minister John Gorton in 1971, and Speaker Billy Snedden in 1984. Mendoza also painted the first sitting of the House of Representatives in this building, in 1988 (completed in 1990).

After the early flush of activity in the period between 1912 and 1920, two world wars and the Great Depression intervened and limited the capacity of the Historic Memorials Committee to meet regularly. Constrained finances also affected the rate at which new portraits were commissioned. Despite this, the collection continued to grow, with the primary focus remaining largely on political figures. Portraits of all governors-general, chief justices of the High Court, prime ministers, and presiding officers of the Parliament have been acquired. In addition to this core group, portraits of other important figures have occasionally been added, such as monarchs, early explorers, and literary figures, and paintings depicting special events, such as the opening of Parliament in Canberra in 1927, and the opening of the new Parliament House in 1988.

Portraits have also been commissioned or purchased of individuals who in some manner represent a parliamentary ‘first’ such as the first women (already mentioned—Enid Lyons and Dorothy Tangney), as well as the first Indigenous Australian elected to Parliament, Senator Neville Bonner, whose portrait was painted in 1979 by Wes Walters.

Today, the Historic Memorials Collection includes almost 250 artworks. The majority are portraits, by eminent Australian artists. In addition to names I have already listed, the HMC includes works by Julian Ashton, George Lambert, John Longstaff, William McInnes, and Ivor Hele. Other significant artists commissioned more recently include Albert Tucker, Sam Fullbrook, Bill Leak, Peter Churcher, Paul Newton, Jiawei Shen, and Rick Amor. Male artists and male subjects are still dominant but with a female prime minister and a female governor-general currently in office, the numbers of women represented in the collection will soon be boosted.

As well as recording Australia’s political history, the collection also reveals changes in the history of portraiture in Australia. As we have seen, the earlier portraits were often sombre in tone and reflected the dignity of the office held by the sitter, borrowing heavily from formal European portraiture. Over time, portraits have tended to become less formal and capture more of the personality of the sitter, sometimes including objects with personal associations, as well as the regalia of office.

The Historic Memorials Collection is a valuable and continuing record of the history of politics and portraiture in Australia. Its centenary provides an opportunity to reflect on the way individual political leaders are portrayed, and how they are viewed by the broader community that the Parliament represents. I hope you can all find time to view some of the portraits in the collection—a large number can be seen here at Parliament House, as well as at Old Parliament House, the High Court, and the National Portrait Gallery.

Question — You mentioned that Tom Roberts measured people when he was making the Big Picture? Do you have any information on how he went about it?

Kylie Scroope — We do know he travelled widely so he visited a number of states in Australia to meet with the people who were represented in the picture. I gather some people were not very happy with the idea. There have even been suggestions that they might have tried to cajole him into reducing their girth, for instance. I suspect there would have been some figures that he wouldn’t have done in that literal sense, particularly the Duke of Cornwall who opened the proceedings. Although Roberts made sketches at the event he also had a couple of sittings with the Duke in England before the painting was completed. I would imagine it was much more just a case of using his artist’s eye with some of the more important dignitaries. But I gather there are notebooks—I think they are mostly held at the National Library—where he made sketches and recorded some of those details like height and weight, hair colour, eye colour and those sorts of things.

Question — Would it be correct to say that before a portrait is commissioned there is a sort of assessment that someone’s career is substantially complete?

Kylie Scroope — Generally the preference is if possible to have the portrait painted while the subject is still in office so that it closely represents the way they looked while they were in that office. But obviously when you are dealing with people like prime ministers in particular or chief justices, they have pretty busy schedules, so that is not always feasible. Certainly there are a substantial number of portraits that have been painted immediately after someone has left office and in the case of Prime Minister Harold Holt, who left office rather suddenly, obviously that portrait had to be painted posthumously. Some of the earlier ones as well, where they only decided to begin the collection after people had passed away, like Sir Henry Parkes. In those cases what usually happened was they made an effort to obtain good quality photographic portraits of the people and then those were given to the artists.

Question — We have seen a very conservative collection of portraits apart from the Clifton Pugh one of Gough Whitlam. Has that been controversial amongst the selection committee that sometimes an artist may have been regarded as a little bit too avant-garde or a little bit too untraditional?

Kylie Scroope — Occasionally. There are rare examples of portraits being submitted and being rejected by the committee. Surprisingly the ones that most often got returned for rework were the earliest ones where I would say they were pretty conservative anyway but obviously the standards they were being judged against were even more conservative then than our tastes would be now. So, for instance, Tom Roberts did a portrait of Lord Tennyson which was sent back to him for rework, which I think is a bit presumptuous considering the stature he would have had as an artist at that time. Considering what we now see in the finished portrait it is hard to imagine what they could have been finding fault with. George Lambert, who was probably one of the more avant-garde artists of that early era, painted a portrait of Sir George Reid in 1913, where unlike most of the other early ones he wasn’t standing, he was seated. If any of you are familiar with George Reid he was a reasonably large man and had a nice round tummy. Because he is seated that is very much emphasised in the portrait and I think one of the news clippings I showed might have made reference to it. There was a lot of both public consternation and consternation amongst the committee. I’ll just read it to you:

the matter of Sir George Reid’s portrait now hanging in Queen’s Hall was mentioned and it was decided that Mr Longstaff should be approached in order to ascertain the price of his picture of Sir George Reid.

So basically they commissioned or obtained a second portrait because Lambert’s was described as being too much of a caricature of the man. There were a couple of other later artists as well whose portraits were rejected. Probably the other best known example was the first portrait of Sir John Kerr by a Queensland artist called Sam Fullbrook—a terrific artist but not necessarily a painter of realist likenesses. So that portrait was rejected without Sir John Kerr ever having any input into the decision and a second portrait was obtained.

Question — Were any actually rejected by the subject?

Kylie Scroope — There was one, I believe—Malcolm Fraser’s first portrait which he expressed considerable concern about. That was painted by Bryan Westwood, one of the artists we looked at. It was a standing portrait, highly realist, and I think the view that was expressed was that it made Malcolm Fraser look like a very intimidating character—probably a highly accurate representation of the way he was when he was prime minister. I think that his persona is quite different now. The Visual Arts Board, who by then were playing the role of the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board, had endorsed it as an acceptable portrait and a number of the members of the Historic Memorials Committee had endorsed it. Because of Mr Fraser’s concerns the committee was eventually persuaded that a second portrait should be obtained.

Question — How do you see the place of the Historic Memorials Collection in the overall conceptual basis of the art program for Parliament House and in the four years that you have been here are you aware of any changes in attitudes towards its relative importance vis-à-vis the rest of the collection or any changes you are aware of since the building opened in 1988?

Kylie Scroope — Not significant changes, I would say. Just to go back a step, when this building was being built there were a number of committees that were involved in various decision-making processes relating to this building and the overall role was played by a joint standing committee of parliamentarians who were established to manage the process. They did a lot of the work on briefing the architects and that sort of thing. For those of you who don’t know, the art collection in Parliament House is considered to be very much an integral part of the building. It wasn’t added as an afterthought, it was developed as a concept right through the whole process of the architecture being developed. The joint standing committee took advice from a body, I think it was called the Presiding Officers’ Reference Advisory Group, about a thing that they called the locational listing. There was also an art advisory group, a separate body, to the Parliament House Construction Authority. So all these groups of different people with different backgrounds and perspectives provided input to the joint standing committee. That committee eventually developed what they called the locational listing which included an item-by-item inventory of material from Old Parliament House that they determined should either be left there or brought to this building.

The majority of the Historic Memorials Committee portraits were deemed to be needed for this building because they so much represent the history of the Parliament. Of course at that stage the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House hadn’t been established and there was a degree of uncertainty about what might happen to that building. But in particular the placement of the portraits around the Members’ Hall was something that was decided and committed to very early on and has remained constant. We have made some minor changes. The number of prime ministers’ portraits that can be displayed in the public areas of this building is relatively limited because we are constrained by the number of wall slots. There used to be only 12 of them on display but a couple of years ago there was some concern that the portrait of John Curtin was about to be displaced so that another portrait could hang and in response to the public concern about that we put a proposal to the presiding officers that we could relocate some of the other portraits to provide more space for prime ministers. So we now have 16 portraits of former prime ministers on public display. The parliamentary ‘firsts’, who used to be in Members’ Hall, are now further out the front of the building.

So I would say minor adjustments. But I think generally, particularly for the members of Parliament themselves, those of them with a strong interest and commitment to parliamentary history would always see it as an essential thing that the core of the Historic Memorials Collection is displayed here. But we are lucky of course that we have institutions like the High Court, the Portrait Gallery and Old Parliament House now that can also display the ones that can’t be displayed here.

Question — You have just mentioned the High Court and the portraits that are there are absolutely stunning, but I have to make the comment that they are so high up the wall that the actual plaques that go with them providing information cannot be read. Is that something that you can address or does it have to be done through the High Court?

Kylie Scroope — It is something the High Court would have to address but I can tell you that it is something they are looking into themselves and I think probably within the next few months it should be addressed. It does illustrate the difference with a building where the artworks were added later, almost as an afterthought, compared to this building where the building was very much designed with display of art as part of its purpose.

Question — Do you see a time when the portraits will be replaced by digital images?

Kylie Scroope — I don’t think so. It is really interesting, even back in 1911 when the collection was first established there was talk about acquiring photographic portraits as well and busts in stone. But curiously, while they did acquire photographic images to use as references, particularly where a portrait was being painted of someone who wasn’t alive any more, they have never really been retained as part of the core collection. I think there is still something about a painted portrait that provides a degree of distance, perhaps, and also makes it a bit more special. If you go to the National Portrait Gallery you will see that they acquire portraits in a much broader range of media—they have things like textiles, lots of photographic portraits, relief images, that sort of thing. The technical prescription for the HMC portrait commissions is still very controlled in that they have to be oil paintings on canvas, they have to be within a certain size range, they have to be framed in a manner that is considered suitable for the collection and that sort of thing. There is certainly no push at this point to change it. I suppose the only thing that might change it is that eventually there might be less people painting portraits but there is no sign of that happening yet, there are plenty of competent portrait artists around still to take these sorts of commissions on.

Question — You said that the Big Picture was in the Royal Collection and lent back to us. How does it come to pass that such an important picture was in the Royal Collection and not here and how did it come back here?

Kylie Scroope — Strangely enough the Big Picture was a private commission. So it was a group of Melbourne businessmen, who I think called themselves something like the Australian Art Association, who basically undertook to offer this commission and they were the ones who set out some of the basic requirements like that it had to include accurate likenesses of a large number of the people there. Various historians have suggested that their primary motivation was in fact commercial. There were photogravure reproductions made of the Big Picture—mass produced print forms of it—and they sold widely not only in Australia but all around the world. They were produced by a French printing company who specialised in that kind of thing. So it had been suggested that the group of people who commissioned the work weren’t really that interested in a major commemorative artwork, they were looking for something to form the basis of a cheaper commercial product that they could then exploit.

But in any case, when the painting was completed that group of businessmen presented it as a gift to the King. King Edward had become monarch just before Parliament opened when Queen Victoria died, but he wasn’t at the opening—he sent his second son. And so the portrait was sent off to England to the Royal Collection and from what we can gather it stayed in St James’s Palace until the 1950s. There were occasional rumblings about the fact that it was there and not here and that really came to a head in the 1950s when Senator Dorothy Tangney in particular lobbied Prime Minister Robert Menzies very hard to advocate for its return. Menzies eventually engaged the secretary of the Governor-General who undertook to get the Governor-General to write to the Palace saying, ‘we think this is a really important part of Australia’s history, would there be any scope for returning it to Australia?’ The response of the royal household was that because it had been a gift they would offer it on permanent loan. So for the last 53 years it has been here.

The sad thing was that when it finally came back to Australia in 1958 I don’t think they anticipated just how big it was and it was actually quite difficult to find anywhere big enough to hang it. It did spend a little bit of time in Old Parliament House on display and it also did a little tour of some of the major state galleries, but it spent quite a lot of time languishing in storage because there was nowhere big enough to show it until the new High Court building opened in 1980 and finally there was a big concrete wall and it was there until this building opened. But as you can see when you look at the place where it is located here, again the architect consciously designed a space for its display. So the area where that little balcony is and the curved wall, architecturally it echoes the visual references.

Question — In 1927 the Duchess of York was given a book of sketches by Eirene Mort and they were sketches of Canberra, and in relation to the centenary of the naming of Canberra in 2013, I wondered if we could get them back for an exhibition and any other picture or works they have of Canberra? Have we ever investigated what they have of Canberra?

Kylie Scroope — It is not something we have looked into. It is possible some of the other institutions may have. I guess the Big Picture is proof that these things won’t happen quickly but they are not impossible. In the case of the Big Picture it was probably about four or five years of toing and froing and correspondence at various levels but eventually it did happen and there is no push to take it back.