Chapter 16

Committees

Like most representative legislative assemblies in free countries, the Senate delegates some of its tasks, and the powers to carry out those tasks, to committees of its members.

This chapter examines the role of the several types of committees before considering their appointment, membership, powers and the conduct of their proceedings. Provisions for the operation of standing and select committees are in chapter 5 of the standing orders. Witnesses are covered in the following chapter.

Role of committees

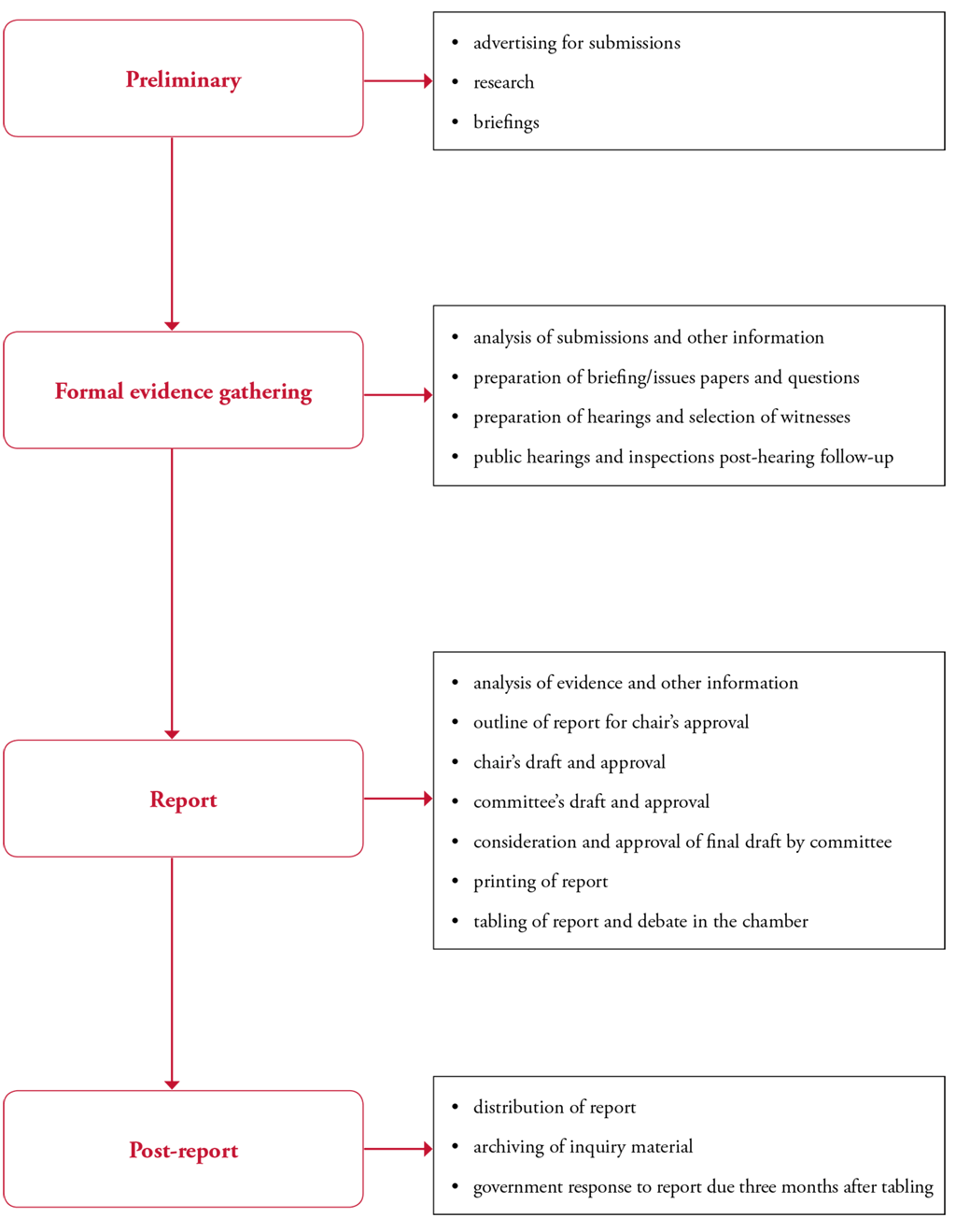

The task most often given to committees is that of conducting inquiries: of inquiring into specified matters, particularly by taking submissions and hearing evidence, and reporting findings on those matters to the Senate. Although the Senate may conduct inquiries directly, committees are a more convenient vehicle for this activity.

Apart from conducting inquiries, committees may be required to perform any of the functions of the Senate, including its primary legislative function of considering proposed laws, the scrutiny of the conduct of public administration and the consideration of policy issues.

The Constitution recognises committees as essential instruments of the Houses of the Parliament by referring in section 49 to: “The powers, privileges, and immunities of the Senate and of the House of Representatives, and of the members and the committees of each House ...”.

The Senate makes extensive use of committees which specialise in a range of subject areas. The expertise built up by those committees enables them to be multi-purpose bodies, capable of undertaking policy-related inquiries, examining the performance of government agencies and programs or considering the detail of proposed legislation in the light of evidence given by interested organisations and individuals. The scrutiny of policy, legislative and financial measures is a principal role of committees.

Most significantly, committees provide a means of access for citizens to participate in law making and policy review. Anyone may make a submission to a committee inquiry and committees will normally take oral evidence from a selection of witnesses who have made written submissions. Committees frequently meet outside Canberra, thereby taking the Senate to the people and gaining first hand knowledge of and exposure to issues of concern to the public.

Inquiries by committees allow citizens to air grievances about government and bring to light mistreatment of citizens by government.

Specialist committees support the Senate's ability to monitor delegated legislation made by the executive government and to ensure that all proposals for legislation do not trespass against fundamental personal rights and liberties. In the Australian Parliament, only Senate committees perform this role.

An important outcome of committee work is the opportunity senators gain to pursue special interests and build up expertise in aspects of public policy, enhancing the quality of debate and providing a solid grounding for backbenchers who may go on to be committee chairs, shadow ministers, party spokespeople or ministers.

The characteristic multi-partisan composition and approach of committees also provides opportunity for proponents of divergent views to find common ground. The orderly gathering of evidence by committees and the provision of a forum for all views can often result in the dissipation of political heat, consideration of issues on their merits and the development of recommendations that are acceptable to all sides:

It is in the conference [i.e., committee] room that careful, calm consideration can be brought to bear upon a subject, and [senators] can work harmoniously in spite of party differences. It is there that the qualities and experience of the individual can be applied to matters under discussion. It is there that opportunity is provided for vision, judgment and experience to be applied and, later, brought before the Senate for open discussion and action.

Types of committees

Leaving aside committees of the whole, committees are of two main types: standing committees, which remain in existence and inquire into matters within their areas of responsibility referred to them by the Senate; and select committees, which are appointed to inquire into particular matters and which cease to exist when they have finally reported on those matters.

Standing committees may be subclassified according to their functions. Joint committees, committees of both Houses, are best treated as a separate category. This produces the following classification, which is employed in this chapter:

- standing domestic committees;

- standing legislative scrutiny committees;

- legislative and general purpose standing committees (including legislation committees considering estimates);

- select committees; and

- joint committees.

Evolution of the committee system

The Senate's first standing orders provided for the establishment of both standing and select committees. The standing or domestic committees were concerned with the Senate's own affairs and support services and included a Standing Orders Committee, Library Committee, House Committee, Printing Committee and Elections and Qualifications Committee. The first committee reports in 1901 were made by the Elections and Qualifications Committee and the Standing Orders Committee. Select committees were used to inquire into particular matters the Senate considered worthy of inquiry. Such committees were given powers to summon witnesses and require the production of documents, and procedures for examining witnesses were set out in the standing orders. The first select committee report presented to the Senate examined steamship communication between Tasmania and the mainland. Other select committees were appointed as required.

In 1932, the Regulations and Ordinances Committee was established following a report of the select committee appointed in 1929 to consider, report and make recommendations upon the advisability or otherwise of establishing standing committees of the Senate upon:

- statutory rules and ordinances

- international relations

- finance

- private members bills

and such other subjects as were deemed advisable.

The select committee was of the view that a standing committee system, to be successful and bearing in mind the small number of senators available (then 36), would need to grow from modest beginnings. Although the select committee originally recommended the establishment of regulations and ordinances and external affairs committees, and the modification of the standing orders to facilitate the reference of bills to committees, the matter was recommitted and the committee's second report recommended that only a regulations and ordinances committee be established. There had been government fears that an external affairs committee might use its powers to obtain access to sensitive documents on Australia's external affairs and the proposal for a committee in this area was not pursued at that time. The significant volume of delegated legislation made without parliamentary scrutiny was of concern to all sides of politics, however, and the establishment of a regulations and ordinances committee was therefore seen as a priority. In 1982 that committee was joined by the second of the standing legislative scrutiny committees, the Scrutiny of Bills Committee, charged with ensuring that all bills and Acts observed similar fundamental principles as those applying to delegated legislation.

The modern committee system dates from 1970, when the Senate agreed to the appointment of seven legislative and general purpose standing committees, standing ready to inquire into any matters referred by the Senate in a range of subject areas, and five estimates committees to examine the annual estimates of departments in a more orderly and effective manner.

With this development, the evolution of the main types of committees on which senators have served was complete.

A major refinement occurred with the adoption of resolutions by the Senate on 5 December 1989 providing for the systematic referral of bills to legislative and general purpose standing committees. These orders came into effect in the latter half of 1990 and facilitated the realisation of a long-held ideal, that Senate committees should have a greater role in the consideration of legislation.

In 1994, as a result of a Procedure Committee report on the committee system, the estimates and legislative and general purpose committees were amalgamated. A scheme of paired committees, incorporating the functions of estimates and legislative and general purpose standing committees in each subject area, a references committee and a legislation committee, was adopted. The chairs of other committees were reorganised so that the distribution of chairs approximated the representation of parties in the Senate. In 2006 the pairs of committees in each subject area were amalgamated, returning to pre-1994 arrangement for the legislative and general purpose standing committees until 2009 when the post-1994 structure was restored.

[update: In 2020, to recognise the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the modern committee system, the Senate department launched two new web resources. The first, Navigate Senate Committees, brings together the history and work of Senate committees since 1901 and charts the genealogy of every Senate committee, with information about chairs and members, links to committee reports, and images and digital media, including oral histories. The second resource, the Senate committees hearing map, illustrates well over a century of Senate committees on the move, comprising more than 7,500 hearings, mapped by subject and year, in over 200 locations.]

Standing domestic committees

There are eight standing domestic committees established by standing order. They are:

- Procedure

- Privileges

- Appropriations, Staffing and Security

- Library

- House

- Publications

- Senators' Interests

- Selection of Bills

Procedure Committee

A descendant of the 1901 Standing Orders Committee, the Procedure Committee is established under standing order 17 and has been in operation under its present name since 1987.

The committee has four ex officio members, the President, Deputy President, Leader of the Government in the Senate and Leader of the Opposition in the Senate. It is chaired by the Deputy President, a provision adopted in 1994. Its remaining six members are appointed from the Senate without any prescribed allocation of places to government or non-government senators. This formula allows as wide a representation of senators as is considered appropriate at any time. The Leaders of the Government and of the Opposition in the Senate are authorised to appoint substitute members when they are unable to attend meetings.

The committee's terms of reference are “any matter relating to the procedures of the Senate referred to it by the Senate or by the President”. The standing orders do not confer formal inquiry powers upon the committee as they are not considered necessary. Most of the matters considered by the Procedure Committee are referred by the Senate. Although it does not formally gather evidence, the committee sometimes invites submissions from senators. A 1993 reference to the committee on the hours of sitting and routine of business included an instruction that the committee invite submissions from all parties in the Senate and independent senators and consult with the Procedure Committee of the House of Representatives, which was undertaking a similar inquiry. In most cases reports are developed following discussions and consideration of issues papers. The committee cannot meet other than in Parliament House without authorisation by the Senate.

Reports of the committee may be considered in committee of the whole to facilitate free discussion of detailed matters, but may also be considered by the Senate. Consideration of the reports may be listed under Government Business orders of the day because, following the presentation of a report, a minister moves the motion to provide for its consideration, or may be listed as an order of the day under Business of the Senate, either by order contained in the reference to the Procedure Committee or following a motion moved on presentation of the report. The designation of Procedure Committee reports as Business of the Senate orders of the day gives priority to their consideration, as befits significant matters of relevance to the conduct of the business of the Senate.

Committee of Privileges

The Committee of Privileges is established by standing order 18, which provides:

- A Committee of Privileges, consisting of 8 senators, shall be appointed at the commencement of each Parliament to inquire into and report upon matters of privilege referred to it by the Senate.

- The committee shall have power to send for persons and documents, to move from place to place and to sit during recess.

- The committee shall consists of 8 senators, 4 nominated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate, 3 nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate and 1 nominated by minority party and independent senators.

- The committee shall elect as its chair a member nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate.

Before 2013, the membership of the committee was seven. It had been increased occasionally, either for the purpose of a specific inquiry or for a period of time. A temporary order agreed to in 2011, increasing membership to eight by the addition of a member nominated by minority party or independent senators, was adopted as a permanent change on 2 December 2013.

As well as inquiring into privilege matters referred by the Senate, which mainly relate to cases of alleged interference with senators or committees, the committee also reports on matters raised with the President of the Senate under Resolution 5 of the Privilege Resolutions, that is, responses by persons to statements made about them in the Senate.

Apart from Resolution 5 matters, inquiries referred have chiefly been of three types: possible unauthorised disclosure of evidence or draft reports; possible misleading evidence given to a committee; or possible interference with, or adverse treatment of, witnesses as a result of their having given evidence. A list of the committee's reports since its establishment in 1966 and consequent action by the Senate is in appendix 3.

In addition to Resolution 5 matters and individual privilege cases referred by the Senate, the committee has also participated in the legislative function of the Senate. In 1994, the committee examined and reported on a private senator's bill, the Parliamentary Privileges Amendment (Enforcement of Lawful Orders) Bill 1994. The bill provided a mechanism for resolving conflicts between the Senate and the executive by providing for questions relating to the failure of ministers and public servants to comply with lawful orders of the Senate, and related issues of public interest immunity, to be resolved by the Federal Court. In its 49th report, the committee concluded that such a bill was not necessary and that the Senate already possessed the powers required to resolve such conflicts. The committee also examined the Tax Laws Amendment (Confidentiality of Taxpayer Information) Bill 2009 recommending the removal of provisions purporting to criminalise the provision of information to parliamentary committees in certain circumstances.

The committee acts as an essential safeguard of the rights of senators and the Senate, and the rights and obligations of witnesses appearing before the Senate and its committees.

Appropriations, Staffing and Security Committee

Standing order 19 provides for the appointment of a Standing Committee on Appropriations, Staffing and Security whose role is to inquire into:

- proposals for the annual estimates and the additional estimates for the Senate;

- proposals to vary the staff structure of the Senate, and staffing and recruitment policies; and

- such other matters as are referred to it by the Senate.

The committee is responsible for determining the amounts for inclusion in the parliamentary appropriation bills for the annual and additional appropriations for the Senate and for reporting to the Senate on its determinations prior to the Senate's consideration of the relevant parliamentary appropriation bill. In relation to staffing, the committee is responsible for making recommendations to the President and reporting to the Senate on any matter. It is required to make an annual report to the Senate on the operations of the Senate's appropriations and staffing and related matters. The committee also oversees the administration, operation and funding of security measures affecting the Senate and, when conferring with a similar committee of the House of Representatives, may consider the administration and funding of information and communications technology services for the Parliament.

The President, the Deputy President, the Leader of the Government in the Senate and the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate are ex officio members of the committee. The Leader of the Government in the Senate may nominate another Senate minister as a representative, thereby ensuring that the government retains a presence on the committee to represent its views. The Leader of the Opposition in the Senate may also nominate a representative. There are six other members, three nominated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate and three nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate or by any minority groups or independent senators. Originally, the committee had seven members but the number was increased to nine when the committee was re-established in May 1983 and ten when the committee was renamed in 2015.

The President is the committee's chair and has the power to appoint a deputy chair from time to time. The chair, and deputy chair when acting as chair, has a casting vote when the votes are equally divided. Senators who are not members of the committee may attend and participate in its deliberations and question witnesses but may not vote.

Unlike the other domestic standing committees, the Appropriations, Staffing and Security Committee has power to appoint subcommittees. Like the Committee of Privileges, it also has power to summon witnesses and to require the production of documents.

See also Chapter 5, Officers of the Senate: Parliamentary Administration, under Senate's appropriations and staffing, and Chapter 13, Financial Legislation, under Parliamentary appropriations.

Library Committee

The Library Committee is established by standing order 20 as follows:

- A Library Committee, consisting of the President and 6 senators, shall be appointed at the commencement of each Parliament, with power to act during recess, and to confer and sit as a joint committee with a similar committee of the House of Representatives.

- The committee may consider any matter relating to the provision of library services to senators.

The President is the chair of the committee.

In 2008 a joint resolution of the two Houses established a joint standing committee and detailed provisions for its composition and proceedings. The President and Speaker are not members of the joint standing committee whose functions arise partly from the enactment of the Parliamentary Service Amendment Act 2005 which established the office of Parliamentary Librarian. Senators appointed under standing order 20, other than the President, are also appointed to the joint standing committee.

The committee invariably sits as a joint committee. Having no powers of inquiry, the committee generally functions as a forum in which to raise and consider matters of relevance to the operations and administration of the Parliamentary Library. It is an advisory committee and the Presiding Officers, with joint responsibility for the Library, are not bound to follow the advice of the committee.

House Committee

The House Committee, established under standing order 21, usually sits as a joint committee with the House of Representatives House Committee. The committee's terms of reference are “any matter relating to the provision of facilities in Parliament House referred to it by the Senate or the President”. Its membership comprises the President, Deputy President and five senators. When it meets as a joint committee arrangements exist for the rotation of the chair between the President and the Speaker. The committee does not possess inquiry powers.

In 1981 the Senate House Committee conducted an inquiry into the organisation, operation, functions and financial administration of the Joint House Department. A resolution conferred powers to summon witnesses and require the production of documents for the purposes of the inquiry. After presentation of the committee's report on 26 August 1982, a follow-up inquiry was referred to the committee which was again given inquiry powers for the purpose. The reference having been renewed, the committee presented an interim report in May 1983.

In 1994, the committee received a reference from the Senate to inquire into the future treatment and use of old Parliament House. A subsequent resolution authorised the committee to summon witnesses and require the production of documents.

Publications Committee

The Publications Committee, established by standing order 22, also normally sits as a joint committee with its House of Representatives counterpart. The committee has seven members but there are no formal conditions attaching to the representation of government and non-government senators.

The committee makes recommendations to the Senate on the printing of documents presented to the Senate and which have not already been ordered to be printed. An order to print a document ensures its inclusion in the series of parliamentary papers; all documents presented to the Senate are ordered to be published. It is usual upon the presentation of committee reports to the Senate for a motion to be moved that the report be printed. The motion is not commonly moved when other documents such as petitions, government documents, delegation reports or reports of the Auditor-General are presented, and it is these which are considered by the Publications Committee at regular meetings in accordance with guidelines determined by the committee. When the Publications Committee reports to the Senate, recommending the printing of certain documents, a motion is moved, by leave, that the report be adopted (leave is required for a motion that would otherwise require notice to be given). The motion may be amended; for example, to provide for the printing of a document not recommended for printing by the committee.

When sitting as a joint committee with the Publications Committee of the House of Representatives, the committee has the following additional powers:

- to inquire into and report on the printing, publication and distribution of parliamentary and government publications and on such related matters as are referred to it by the relevant Minister; and

- to send for persons and documents.

This additional role of the joint committee arose from recommendations of the Joint Select Committee on Parliamentary and Government Publications which were adopted in 1970. The investigatory function is invoked when the committee considers matters relating to Commonwealth publishing. The committee has undertaken inquiries under this function and presented several reports, most recently recommending electronic distribution of the series of parliamentary papers.

In 1993 the committee criticised the presentation of large numbers of annual reports of departments and agencies in the last sitting week before the end of the year. The basis for this criticism was that:

[t]he Committee believes that this situation diminishes Parliament's role in ensuring the accountability of these organisations through their annual reports to Parliament by reducing the opportunity for Members and Senators to critically review and debate matters contained in the reports.

Requirements for annual reports stipulate 31 October as the deadline for tabling. The requirements were part of the revision of accountability documentation stemming from the altered Budget timetable introduced in 1994 and provided under the Public Service Act 1999.

Senators' Interests Committee

Under standing order 22A(1), the functions of this committee are:

- to inquire into and report upon the arrangements made for the compilation, maintenance and accessibility of a Register of Senators' Interests;

- to consider any proposals made by senators and others as to the form and content of the Register;

- to consider any submissions made in relation to the registering or declaring of interests;

- to consider what classes of person, if any, other than senators ought to be required to register and declare their interests; and

- to make recommendations upon these and any other matters which are relevant.

Its membership is required to reflect as closely as possible the composition of the Senate. The committee has a specified membership, which may be varied, of eight senators, three nominated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate, four nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate and one nominated by any minority groups or independent senators. The chair of the committee is a member of the committee nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate. Provision is made for the appointment of a deputy chair and for the chair (or deputy when acting as chair) to have a casting vote when the votes are equally divided.

The committee has power to send for persons and documents and to confer with a similar committee of the House of Representatives. It does not have power to move from place to place. Its inquiry power is qualified by a requirement that any exercise of the power to send for persons and documents, or any investigation of the private interests of any person, must be agreed to by not fewer than three members other than the chair. This is intended to be a safeguard against use of the committee's powers for partisan political purposes.

The committee is required to present an annual report and may also report from time to time. Its main role is to oversee arrangements for the register which is now published online.

The committee was first established on 17 March 1994 following a commitment given by the government as part of a package of “accountability measures” to be pursued in the wake of the forced resignation of the Minister for Environment, Sport and Territories over the administration of the Community Cultural, Recreation and Sporting Facilities Program. The package was announced by the Leader of the Government in the Senate, Senator Gareth Evans, on 3 March 1994. Notices of motion to establish such a committee had languished on the Notice Paper for years through the 1980s and early 1990s.

Selection of Bills Committee

The Selection of Bills Committee, which is established by standing order 24A, makes recommendations to the Senate for the referral of bills to committees. The committee considers bills introduced into the Senate or received from the House of Representatives and reports to the Senate on whether any bills should be referred to legislative and general purpose standing or select committees.

Membership of the committee is based on an informal committee of party whips which meets each sitting day to confer on the day's program. The committee consists of the Government Whip and two other senators nominated by the Leader of the Government, the Opposition Whip and two other senators nominated by the Leader of the Opposition, together with the whips of any minority groups. The chair of the committee is the Government Whip who may from time to time appoint a deputy chair to act as chair when the chair is not present at a meeting. The chair, or deputy chair when acting as chair, has a casting vote when the votes are equally divided.

The committee is required to examine all bills received from the House of Representatives or introduced into the Senate, except for bills containing no provisions other than provisions appropriating money, and, in respect of each bill, recommend whether it should be referred to a legislative and general purpose standing committee. The committee may also refer bills to appropriate select committees. When the committee decides that a bill should be referred to a committee, it is required to recommend which committee should receive the bill, the stage at which it should be referred and the date on which that committee should report.

The standing order establishing the committee does not contain any criteria which the committee is required to follow in making recommendations in relation to bills. This allows the committee to take into account any grounds advanced by senators for the submission of bills to committee scrutiny.

Although few of the committee's reports have indicated the basis on which the committee has made its recommendations, the committee has commented on particular referrals and given reasons why a decision has been made or changed. In its 4th report of 1990, for example, the committee indicated that there was a difference of views about which standing committee a package of social welfare bills should be referred to. Although the committee recommended that the bills be referred to the Community Affairs Committee, an amendment was moved to the motion that the report be adopted, which would have had the effect of referring parts of one of the bills to two different committees. The President ruled on a point of order that a bill could be referred to more than one committee because, although the order of the Senate referred to bills being referred to “a committee”, as a matter of interpretation the singular number is taken to include the plural. The amendment was then agreed to. In its 6th report of 1990, the committee indicated that its decisions not to refer two bills to committees as proposed by the Opposition and Australian Democrats, respectively, had been taken by a majority. One of these recommendations was subsequently overturned by an amendment to the motion that the report be adopted. The committee reviewed an earlier recommendation not to refer a bill in light of comments on the bill by the Scrutiny of Bills Committee. The committee now reserves disagreements for resolution by the Senate. The committee has reviewed recommendations not to refer bills on other grounds, including the circulation of a large number of government amendments to a bill and representations by individual senators. The committee has also reviewed its recommendations on the timing of referrals in view of the demands of a heavy legislative program.

In practice the committee recommends the referral of a bill if a significant group in the Senate ask for the bill to be referred. Submissions seeking the referral of particular bills and identifying issues to be examined are published with the reports. Amendments to motions to adopt the committee's reports, however, are relatively common.

An unusual order passed by the Senate on 14 May 2009, in referring budget-related legislation to committees before its introduction into either House, empowered the Selection of Bills Committee to vary the references. A further refinement to the order, agreed to on 13 May 2010 (and reprised on 12 May 2011 with further streamlining) removed the Selection of Bills Committee from the process and left it to individual committees to determine, by unanimous resolution, which bills did not require examination because they raised no substantive issues.

The committee's reports are presented after the giving of notices of motion, or at other times by leave. Amendments may be moved to the motion that the report of the committee be adopted and these may include amendments to refer additional bills to committees or to change or insert reporting dates where there has been internal disagreement in the committee. Debate on the reports is limited to 30 minutes with a 5 minute limit on individual contributions.

The committee recommends the referral to committees of a significant proportion of all bills considered by the Senate.

Legislative Scrutiny Committees

Standing orders 23 and 24 establish the Regulations and Ordinances Committee and the Scrutiny of Bills Committee, respectively. The purpose of these committees is to monitor primary and secondary legislation to ensure legislative proposals do not tresspass against fundamental rights and liberties.

For further information on these committees, see Chapter 12, Legislation and Chapter 15, Delegated legislation, scrutiny and disallowance.

Legislative and general purpose standing committees

The legislative and general purpose standing committees, appointed under standing order 25, are the engines of the Senate's committee system. First established in 1970, together with a system of estimates committees, these committees, specialised by subject, inquire into and report on matters referred to them by the Senate. The committees have been restructured on three occasions since 1970 with major restructuring occurring in 1994 when a system of paired legislation and references committees was adopted. After a brief return to a unitary system in 2006 (coinciding with the then government's majority in the Senate), the paired system was restored on 13 May 2009.

The committees cover between them all areas of government responsibility and subjects of inquiry. Specific matters, within their subject areas, are referred to them by the Senate. Some “watching briefs” are also referred to them, for oversight of areas of government activity. They have the task of scrutinising annual reports of government departments and agencies and bills referred to them. The allocation of departments and agencies to committees is achieved by a resolution of the Senate which is renewed at the commencement of each Parliament and varied as required with any changes in the government's administrative arrangments orders.

The main features of the committees are:

- eight pairs of committees are established under standing order 25 with a references committee and a legislation committee in each subject area

- references committees inquire into matters referred to them by the Senate, other than matters to be referred to legislation committees

- legislation committees inquire into bills, estimates, annual reports and performance of agencies

- each pair of committees is allocated a group of government departments and agencies

- each committee has six members, with the government party having the chairs and majorities on legislation committees and non-government parties having the chairs and majorities on references committees

- six of eight references committees have opposition chairs while the remaining two are from the largest minority party; allocation of these chairs is determined by agreement between the opposition and the largest minority party and, in the absence of agreement, is determined by the Senate

- committees with government party chairs elect non-government deputy chairs and those with non-government chairs elect government deputy chairs;

- chairs have a casting vote when the votes are equally divided, as do deputy chairs when acting as chairs

- the chair, or the deputy chair when acting as chair, may appoint another member of a committee to act as chair during the temporary absence of both the chair and deputy chair from a meeting

- senators may also be appointed as substitute members, replacing other senators on committees for specific purposes, or as participating members, who have all the rights of members except the right to vote

- provisions authorising other senators who are not members of committees to attend and participate in public hearings apply only to estimates hearings

- committees may appoint subcommittees with a minimum of three members

- subcommittees have the same powers as the full committees, including the power to send for persons and documents, travel from place to place and meet in public or in private and notwithstanding any prorogation of Parliament or dissolution of the House of Representatives

- subcommittees may report only to the full committee, not the Senate

- the pairs of committees may confer together to coordinate their work, and the chairs of these and any select committees form the Chairs' Committee, which meets with the Deputy President in the chair, to consider and report to the Senate on any matter affecting the operations of the committees

- each pair of committees is supported by a single secretariat unit.

The committees therefore have the capacity to perform any of the Senate's roles on its behalf.

The operations of the committees are considered below under Appointment and membership of committees, Powers of committees and Conduct of inquiries.

For further detail on the reference of annual reports and legislation to committees, see below under Conduct of inquiries, Referral of matters to committees. Reports of the legislative and general purpose standing committees are listed in the Department of the Senate's Consolidated Register of Senate Committee Reports now published online. Other, generally historic, information about committees may be found in the following publications:

Senate Legislative and General Purpose Standing Committees: The First 20 Years 1970-1990, Senate Committee Office.

Senate Committees and Responsible Government, Proceedings of the conference to mark the twentieth anniversary of Senate Legislative and General Purpose Standing Committees and Senate Estimates Committees, Papers on Parliament No 12, Department of the Senate, September 1991.

Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs, The Twentieth Anniversary of the Committee, December 1991.

Department of the Senate, Annual Report, various*

Committee Office Information Bulletin, Nos 1-20*

Work of Committees (published biannually from 1994; supersedes items marked *)

Senate Committees and Government Accountability, Proceedings of the conference to mark the 40th anniversary of the Senate's legislation and general purpose standing committee system, Papers on Parliament No. 54, Department of the Senate, December 2010.

Legislation committees considering estimates

Estimates committees no longer exist as a separate category of committee, but the estimates scrutiny functions they performed are carried out by the legislative and general purpose standing committees. When performing those functions the committees are still commonly referred to as estimates committees. Like legislative and general purpose standing committees, estimates committees came into existence on 11 June 1970 as part of the modern committee system in the Senate. The estimates scrutiny role of the committees is provided by standing order 26, under which the old estimates committees used to be established.

Estimates scrutiny is an important part of the Senate's calendar and a key element of the Senate's role as a check on government. The estimates process provides the major opportunity for the Senate to assess the performance of the public service and its administration of government policy and programs. It has evolved from early efforts by senators to elicit basic information about government expenditure to inform their decisions about appropriation bills, to a wide-ranging examination of expenditure with an increasing focus on performance. Its effect is cumulative, in that an individual question may not have any significant impact, but the sum of questions and the process as a whole, as it has developed, help to keep executive government accountable and place a great deal of information on the public record on which judgments may be based.

Procedures currently applying to the consideration of estimates are as follows. Twice each year, particulars of proposed expenditure are referred to the committees. The particulars are derived from the two sets of appropriation bills normally introduced twice each year. Portfolio Budget Statements, tabled in May, and Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements, tabled in February, assist the committees in their examination of the particulars. Under an order of the Senate of 2004, amended in 2006, the annual tax expenditures statement stands referred to committees considering estimates. Annual reports of agencies, required to be tabled by 31 October each year, are available for consideration in the context of an agency's performance over the previous financial year. Since the enactment of the Charter of Budget Honesty Act 1998, information required by that Act to be produced is also available to committees, along with other information contained in Budget papers. This includes the mid-year economic and fiscal outlook report (MYEFO) and the final budget outcome report. Statements of expenditure from the Advance to the Finance Minister under the Appropriation Acts, once a significant accountability vehicle in the absence of other such information, have diminished in importance, including because the Appropriation Acts now represent a relatively small proportion of total Commonwealth expenditure.

Supporting documentation provided by departments is significant to the estimates scrutiny process, and has evolved with the process. From the early 1970s, departments provided explanatory notes to the committees examining estimates. These notes were rudimentary at first and were provided informally to members of estimates committees. As a result of pressure from committees the documents were formally tabled in the Senate from 1976. The introduction of program budgeting in the public sector in the 1980s saw the documents transformed from explanatory notes to program performance statements which provided explanations according to the new program structure and which were also promoted by the Department of Finance as an accountability tool, used for improving program management and evaluation, as well as for providing information to the Senate. Documentation underwent a further change in 1994, when the movement of the Budget from August to May meant that documentation provided for Budget estimates (Portfolio Budget Statements) could not provide the extent of performance information that the Senate was used to. Performance information is now found in annual reports of agencies, required to be tabled by 31 October each year, and which may be examined by the committees when considering estimates. The move to output-based accrual budgeting reinforced the requirement for detailed explanatory material on departmental activities. The committees considering estimates have thus encouraged improvements in the quality, nature and transparency of information presented to Parliament. In successive reviews, governments have recognised the need to align appropriations, Portfolio Budget Statements and the information contained in annual reports to allow comparison of planned and actual performance.

Committees hold initial hearings at which the responsible minister, or representative, and officers appear to answer questions on their respective programs. Although the Senate permitted parliamentary secretaries to appear before estimates committees in the past, an increase in the number of ministers in the Senate following the 1993 election led the Senate to agree to an order ending this practice. This prohibition was subsequently relaxed to allow parliamentary secretaries to represent ministers other than Senate ministers in relation to the latter's own responsibilities. Although it is desirable that a minister be present at the hearings, it is not required by standing orders. [update: There is occasionally a suggestion that the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) does not attend estimates. In fact, secretaries of PM&C have appeared on several occasions, including consecutive appearances in the February and May estimates rounds in 2021.]

Days are set aside for examination of the estimates and on such days the Senate usually does not sit to enable the committees to meet (in earlier years it adjourned early). On occasions committees considering estimates have been authorised to meet while the Senate was sitting. When the Senate was “recalled” under standing order 55 on 3 November 2005, scheduled estimates hearings were authorised to proceed.

The committees are free to set additional times for estimates hearings if they so choose but orders of the Senate agreed to on 25 June 2014 bolstered the rights of the non-government minority on legislation committees to insist that additional hearings be scheduled where needed. Any such additional hearings would have to occur before the time set by the Senate for the committees to report. As there is no requirement for the committees to report after the supplementary hearings (see below) such additional hearings could be held at any time up to the next round of regular hearings. Thus, in the supplementary hearings in early November 2006, the Economics Committee decided to hold an additional hearing later in November.

Committees have been directed by the Senate to hold supplementary hearings on estimates. In 2008 the Community Affairs Committee was directed to hold “cross-portfolio” estimates hearings on Indigenous affairs. Such hearings are now a regular feature of the estimates cycle, although changes in administrative arrangements in 2013 led to the cross-portfolio hearings being conducted by the Finance and Public Administration Legislation Committee. [update: Similarly, cross-portfolio hearings on Murray-Darling Basin matters are conducted by the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee during each round of estimates under an order first agreed to in 2017: 29/3/2017, J.1221.]

The committees have power to call for persons and documents and may also move from place to place, although no committee considering estimates has yet done so [update: The first (and, to date, only) estimates hearing to occur outside Canberra was a hearing of the Environment and Communications Legislation Committee, which examined NBN Co. nbn co. in Sydney in November 2017. Although for some years estimates hearings had occasionally taken evidence from witnesses by phone or video link, the requirement for “COVID-safe” hearings in the Budget estimates round of 2020-21 saw some senators and ministers, as well as numerous officials, participating remotely.].[update: Similar practices were adopted to varying degrees during subsequent rounds.]

Estimates hearings are required to be in public and the committees when considering estimates are not empowered to receive confidential material in the absence of a specific resolution of the Senate to that effect. All such material received by a committee is automatically published. Although the Senate in 1981 agreed to consider whether estimates committees should be able to take evidence in camera, the Procedure Committee has on several occasions recommended against such a change, and the Senate has accepted those recommendations.

Similarly, because estimates hearings are required by standing order 26 to proceed by way of calling on items of proposed expenditure and seeking explanations from ministers and officers, the committees are not empowered, in the course of estimates inquiries, to adopt inquiry techniques which are available to them in their other activities, such as showing video recordings, participating in product demonstrations or undertaking on-site inspections.

No more than four committees may meet in public simultaneously. This provision is intended reasonably to accommodate the interests of senators in the estimates of several departments.

Procedures applying to Senate committees generally apply to estimates hearings in so far as those procedures are consistent with standing order 26. For example, the procedures for the protection of witnesses in Senate Privilege Resolution No. 1 apply to estimates hearings, but as standing order 26 requires that estimates hearings be held in public, the provisions in those procedures relating to taking evidence in camera cannot apply to estimates hearings. Similarly, standing order 25(13) which discourages legislative and general purpose standing committees from inquiring into matters being examined by select committees cannot prevent questions being asked at estimates hearings about such matters because such questions are not, in themselves, inquiries and the estimates hearings are intended to cover “particulars of proposed expenditure”, subject only to the test of relevance. [update: For example, in a Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee estimates hearing on 28 February 2017, a senior official of the Attorney-General’s Department expressed reluctance to “traverse matters that are the subject of inquiry by another committee”, being the Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee inquiry into the liquidation of the Bell Group of Companies. There is no rule of the Senate that prevents senators seeking explanations on such matters at an estimates hearing, and the chair allowed the questions to proceed.]

At each hearing, the committee chair calls on the items of proposed expenditure, usually by reference to the programs and subprograms for which funding is described in the Portfolio Budget Statements or Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements. The estimates are then open for examination. Committees may also consider the annual reports of departments and budget-funded agencies in conjunction with their consideration of estimates.

[update: As with any other hearing, a committee considering estimates sets its program beforehand and any adjustments require agreement. The method of proceeding echoes earlier procedures for considering appropriation bills in committee of the whole. The chair calls on items of proposed expenditure in the agreed order, generally at agency or program level, and opens those items for questioning. In committee of the whole, questioning continues until senators had no further questions on that item. Generally, estimates committees have been able to achieve a similar outcome, by agreement, and by the development over time of processes for placing questions on notice.

In 2013 and 2014, after some disquiet about the allocation of questions among senators and about committees adjourning while senators still had questions to ask, the Senate agreed to new procedures affecting the management of estimates hearings. These include procedures requiring committees to schedule further hearings on the initiative of any three members (see now continuing orders 9A and 9B) and an amendment to standing order 26(4) that limits the ability of the chair to move through the committee’s agreed program. The standing order provides that the chair cannot call on the next item if any senator has further questions on the current item, unless:

- the senator agrees to place their questions on notice; or

- the committee agrees to schedule an additional hearing to allow those questions to be asked.

One consequence is that standing order 26(4) also operates to extend a hearing beyond its scheduled adjournment time unless senators with further questions agree to place them on notice, or the committee agrees to schedule a further hearing. The provisions for spill-over hearings under continuing orders 9A or 9B could be used to secure a further hearing, as could a simple decision of the committee.

A decision of the committee made at any time to schedule a further hearing on the item then before the committee allows the chair to move to the next item on the committee’s program or, in the circumstances described above, to adjourn the hearing at the scheduled time.

Committees may also consider the annual reports of departments and budget-funded agencies in conjunction with their consideration of estimates.]

Questions taken on notice at estimates hearings

Most questions are answered at the hearings, but witnesses may also choose to take questions on notice and provide written responses after the hearing. Members and participating members may also place questions on notice. Such questions are lodged with the secretaries of the committees, and are distributed to members of the committees and to relevant departments. As any senator may participate in estimates proceedings, any senator may place questions on notice. Once questions are lodged they are in the possession of the committees and cannot be withdrawn by the senators who lodged them. There is limited time for estimates questions on notice to be lodged, and the withdrawal of questions after they are lodged could deprive other senators of the right to have the questions answered.

Questions may be lodged while there are estimates proceedings in process, that is, from the time of the reference of the main or additional estimates to the committees to the time when the committees report. In the case of the supplementary hearings on the main estimates (see below), when reports are not usually required and committees have the capacity to schedule additional hearings, committees are free to make their own decisions about deadlines. Questions lodged during the supplementary hearings must relate to matters notified for consideration in those hearings.

A senator, on any day after question time in the Senate, may seek an explanation of, and initiate a debate on, any failure to answer an estimates question on notice by the deadline set by the committee for answering such questions. [update: The Senate has by resolution set a deadline to answer unanswered estimates questions from a previous parliament as a trigger for the use of this procedure in the following parliament (31/8/2016, J.81; 29/7/2019, J.258) and, similarly, from one session of the 44th Parliament to the next: 19/4/2016, J.4134.] In 2014, the Senate agreed to an order of continuing effect for the production of information about answers provided to questions taken on notice at each round of estimates hearings, to monitor compliance with commitee deadlines. Frustration with delays in providing answers to questions on notice has been a perennial topic at estimates hearings.

In November 2004 the Senate adopted a special procedure to substitute questions on notice for supplementary estimates hearings.

Scope of questions at estimates hearings

The committees when considering estimates are authorised to ask for explanations from ministers in the Senate, or officers, relating to the items of proposed expenditure. Usually the committees leave it to the minister to determine which witnesses attend, although they have the power to call particular witnesses if they so choose. On many occasions in the past, however, ministers have cooperated with committees in agreeing to the attendance of particular witnesses. [update: The Senate has occasionally directed that particular Senate ministers, or particular officers, appear at estimates: for example, President of Fair Work Australia, 28/10/2009, J.2661-2 (subsequently relaxed to an expectation the President would appear should the committee require it: 13/11/2013, J.100); Treasury Secretary, 13/5/2010, J.3494; named Defence officer, 23/2/2016, J.3774; named NBN Co. officers, 14/11/2017, J.2213; Minister for Employment, 16/11/2017, J.2259; 3/4/2019, J.4838-40; officers of the NSAB, 12/2/2020, J.1346. Directions that ministers attend as committee witnesses had not occurred before 2016: see Chapter 17—Witnesses, under Senators as witnesses.The Senate has also requested (rather than compelled) the attendance of persons who were formerly officers of a department allocated to a committee, one of whom attended and answered questions: 15/2/2018, J.2741.]

Although the reference in standing order 26(5) to ministers or officers might be taken to limit estimates hearings to public bodies and office-holders, non-government bodies in receipt of public funds have appeared by agreement to answer questions. [update: For instance, in the 2017-18 Budget estimates round, the Snowy Hydro Corporation, in which the Commonwealth has a 13% stake, appeared before the Environment and Communications Legislation Committee, while Dairy Australia, whose funding sources include a levy paid by milk producers, as well as Commonwealth and state governments, universities and research organisations, appeared before the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee. Similarly, in the 2020-21 Budget estimates round, a number of publicly funded boards and corporations were called, including the Naval Shipbuilding Advisory Board, Defence Housing Australia, the Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority and the Board of Australia Post, the latter Board agreeing to appear after a senator foreshadowed a Senate motion requiring their attendance.]

The only substantive rule of the Senate relating to the scope of questions is that questions must be relevant to the matters referred to the committees, namely the estimates of expenditure. Any questions going to the operations or financial positions of departments or agencies are relevant questions. The Senate on 22 November 1999 endorsed the views of the Procedure Committee on the relevance of questions at estimates hearings. This followed earlier disputes between committee members and ministers about relevance of questions. The Procedure Committee adopted advices provided to those members by the Clerk of the Senate. As the estimates represent departments' and agencies' claims on the Commonwealth for funds, any questions going to the operations or financial positions of the departments and agencies which shape those claims are relevant.

[update: The Procedure Committee went on to say “provided that questions are asked in an orderly fashion and meet the test of relevance the questions are in order.” Despite this clarity, it is sometimes suggested that the rules for Senate questions in standing order 73 apply to estimates. There is no basis for this suggestion, so there are no grounds for a chair to rule on whether questions at estimates conform with those rules.

The only other rule going to the content of questions is the provision in privilege resolution 1(16) that officers “shall not be asked to give opinions on matters of policy…” These rules are identified in the chair’s opening statement recited at the start of each hearing.

It is unsurprising that the rules for Senate questions do not apply. Estimates hearings did not evolve from question time, but from the examination of appropriation bills in committee of the whole: see Laing, R.G, Annotated Standing Orders of the Australian Senate, standing order 26.

One constraint on the broad test of relevance described above lies in the Senate resolution allocating the oversight of executive portfolios to different committees. For this reason, some questions asked in two estimates hearings during the 2017-18 additional estimates round were ruled not relevant. With this principle in mind, an unusual order required a Senate minister to attend estimates to answer questions in relation to a portfolio she no longer held: 3/4/2019, J.4838-4840. Similarly, questions were asked of an officer in connection with a former role in the same department, on the basis that no question of relevance arose, although the officer availed himself of the right to refer detailed questions to a superior officer: Legal and Constitutional Affairs Legislation Committee, Budget estimates, transcripts, 19/10/2020, pp 82-86; 20/10/2020 pp. 143-7. Estimates chairs have sometimes allowed questions about officers’ former roles in other portfolios despite technically breaching this test of relevance, particularly where it was apparent that the officer was willing to answer them: Economics Legislation Committee, Budget estimates, transcript, 26/10/2020, p.32.]

Annual reports are statements to Parliament of the manner in which departments use the resources made available to them, and therefore references to annual reports are relevant. When the budget cycle was changed so that the main estimates were presented in May instead of August, this necessarily involved the most relevant annual reports not being available at the time of the main estimates hearings but becoming available at the time of the additional estimates hearings. It was therefore accepted that annual reports would be referred to during the additional estimates hearings. In effect, annual reports disclose the financial positions of departments and their activities leading to their financial positions at the very time when departments are seeking additional funds as a result of their financial positions.

Role of the Australian National Audit Office

An important factor is the availability of audit reports and the participation of officers of the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) in committees' examination of programs which have been subject to efficiency and project audits by ANAO. Guidelines for provision of assistance by the Auditor-General to committees considering estimates were drawn up in 1986 following a meeting between the Auditor-General and the President and chairs of the former estimates committees. The Auditor-General produces regular reports on departments and their financial statements, on individual efficiency and project audits, and special audits. The chief assistance provided by the Auditor-General is by way of briefings for committees on reports, and throughout the estimates process if required. Although ANAO staff do not attend estimates hearings as a matter of course, it is open to committees to invite the Auditor-General to provide comment, or nominate ANAO officers to provide comment, on matters relevant to audit reports raised during committee hearings. On a small number of occasions, this assistance has taken the form of ANAO officers appearing as witnesses before committees considering estimates, to provide comment on audits conducted within the relevant program. During its consideration of the 1993 Budget estimates, for example, Estimates Committee A invited ANAO officers to give evidence on two separate organisations, the Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, both of which had been subject to recent audits. In its report to the Senate, tabled on 7 October 1993, the committee commented that the provision of public evidence by ANAO officers had been helpful to the consideration of the proposed estimates. On another occasion, in 1989, ANAO officers gave evidence to Estimates Committee E on audits conducted on the Aboriginal Development Commission and Department of Aboriginal Affairs.

[update: More recently, in 2017, officers of ANAO appeared before the Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport Legislation Committee to assist with questions about an ANAO report into the conduct of a tender. The audit had been undertaken following correspondence from the committee to the Auditor General in the previous parliament, raising concerns about the performance of an agency, Airservices Australia. After ANAO officers gave evidence, the agency appeared before the committee; ANAO was then asked to clarify evidence, before the agency was again called. Similarly, ANAO officers appeared before the Environment and Communications Legislation Committee during the 2021-22 Budget estimates hearings to assist with questions arising from audits connected to the portfolios allocated to that committee.]

Supplementary estimates hearings

After initial hearings have been completed, the committees present reports to the Senate. They are also required to set a date for receipt of answers to questions taken on notice prior to and at the hearings. In relation to the annual estimates, but not the additional estimates, the committees are required to set a date or dates for supplementary hearings to consider answers to questions on notice or any other matters relating to the proposed expenditure of which members and participating members have given notice that they wish to pursue. The date set for the commencement of supplementary meetings must not be less than 10 days after the date set for receipt of answers to questions taken on notice. In practice in recent years, the Senate has set the dates for supplementary hearings. Senators must give notice of matters they wish to pursue not less than three working days before the date for commencement of the supplementary meetings.

Matters considered at supplementary hearings are confined to those matters of which notice has been given but the tendency in recent years has been for such matters to be framed in broad terms. Committees may present further reports to the Senate containing recommendations for further action by the Senate, although they are not required to do so. There is no limit to the number of supplementary hearings a committee may hold, but after the time for giving notice of matters to be raised at supplementary meetings has expired, there is no further opportunity to give notice of additional matters. In a report on its supplementary meetings in November 1993, Estimates Committee F recommended that the Procedure Committee examine a system for giving notice of matters in respect of a particular portfolio not less than three days before the commencement of supplementary hearings on that portfolio. The recommendation was adopted by the Senate after it had been moved as a second reading amendment to the appropriation bills by the chair of Estimates Committee F. The Procedure Committee declined to recommend a change to the procedures on the grounds that the existing arrangements offered clarity and simplicity and the proposed change would make programming of supplementary meetings more difficult.

In 2001, on the recommendation of the Procedure Committee, supplementary hearings were confined to the annual appropriation bills, and abolished in respect of the additional appropriation bills. The rationale of this change was that, as the budget cycle had developed, the supplementary hearings for the additional appropriation bills were occurring very near to the main round of the annual appropriation hearings, when unlimited questioning of departments and agencies is possible.

It is not necessary for the committees to have completed their hearings before debate on the appropriation bills resumes, or, indeed, before the bills are passed. Normally, however, the hearings are completed before the bills proceed.

For the earlier history of changes to the estimates scrutiny process, see OASP 12th ed., Chapter 13, Financial Legislation, pp. 313-16, under History of expenditure scrutiny.

Select committees

Since 1901, select committees have provided the Senate with the ability to conduct ad hoc inquiries. Select committees are inherently responsive to the needs and composition of the Senate at any time and they can react quickly to the Senate's requirements. Unlike standing committees, they cease to exist when they have reported upon the matters referred to them.

In 1970 there was an expectation that the standing committees then established would avoid the need for many select committees. With the emergence and maturing of the legislative and general purpose standing committees, it was expected that most matters would be referred to standing committees because of their readiness and expertise. In its report on the committee system in 1994, the Procedure Committee observed that select committees and their chairs would continue to be appointed on an ad hoc basis, depending on the needs of the Senate. The committee suggested, however, that the Senate might have “as a goal the existence of no more than two select committees at any time”. At the time the report was presented there were four select committees. Within a month of the Senate's agreeing to adopt new standing and other orders giving effect to the Procedure Committee's report, a further select committee was appointed.

The Senate has continued to make use of both standing and select committees, although there have been informal attempts to limit the number of select committees operating at any one time to two. Appendix 8, Committees on which senators serve, shows the numbers of committees operating in the Senate, and indicates that select committee activity has remained vigorous.

There are several reasons for this. Select committees are an extremely versatile inquiry vehicle. Because they examine single issues, select committees permit a concentration of focus and effort on those issues. While they may undertake short, sharp inquiries, select committees are also appropriate vehicles for lengthy and sustained inquiries. Whereas many legislative and general purpose committee inquiries proceed on a multi-partisan basis and result in unanimous reports, select committees often function in a highly politically charged environment in which a great deal of political heat is generated and unanimous reports are unlikely and unlooked for. Select committees can also be the vehicles for relatively uncontroversial, wide-ranging and effective inquiries into subjects which do not fit readily into existing committee arrangements.

A list of select committees from 1901-1985 may be found in ASP, 6th ed., at pp 745-6. Since 1985 (the currency of the 6th ed.), select committees have been appointed by the Senate as shown in appendix 9.

Usually the powers and procedures of select committees are provided for in their resolutions of appointment. Otherwise, the general provisions relating to committees in standing orders 27 to 42 apply. Select committees are required to have a specific reporting date, which may be varied by agreement of the Senate. Unless otherwise provided in the resolution of appointment, a select committee chair has a deliberative vote only. The Senate may give a committee inquiry powers, including the power to call for persons and documents.

For a select committee to commence its inquiry on the publication of a treaty, see the Select Committee on the Free Trade Agreement Between Australia and the United States.

The standard resolution of appointment for select committees usually contains the following elements:

- That a select committee, to be known as the Select Committee on ............................. be established to inquire into and report upon:

- ....................................................;

- ....................................................; and

- .....................................................

- That the Committee present its final report on or before ....................... ......................

- That the Committee consist of X Senators, as follows:

- X to be nominated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate;

- X to be nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate; and

- X to be nominated by minority groups or independents.

- That the committee may proceed to the dispatch of business notwithstanding that all members have not been duly nominated and appointed and notwithstanding any vacancy.

- That the committee elect as chair one of the members nominated by the ....... ...................................... and, as deputy chair, a member nominated by ..................

- That the deputy chair shall act chair when the chair is absent from a meeting of the committee or the position of chair is temporarily vacant.

- That, in the event of an equality of voting, the chair, or the deputy-chair when acting as chair, have a casting vote. [If not specified, SO 31 applies.]

- That the committee and any subcommittee have power to send for and examine persons and documents, to move from place to place, to sit in public or in private, notwithstanding any prorogation of the Parliament or dissolution of the House of Representatives, and have leave to report from time to time its proceedings and the evidence taken and such interim recommendations as it may deem fit.

- That the committee have power to appoint subcommittees consisting of X or more of its members, and to refer to any such subcommittee any of the matters which the committee is empowered to consider.

- That the committee be provided with all necessary staff, facilities and resources and be empowered to appoint persons with specialist knowledge for the purposes of the committee with the approval of the President.

- That the committee be empowered to print from day to day such papers and evidence as may be ordered by it, and a daily Hansard be published of such proceedings as take place in public.

There are few specific requirements relating to the membership of select committees. The standing orders retain the provision for committee members to be nominated by the mover of the committee but this provision is rarely used to select named senators to serve on the committee. The more common approach is for the mover of a committee to nominate a membership formula along the lines of paragraph (3) of the model resolution of appointment above. It is also increasingly common for select committees to have participating members. If this is required, provisions based on standing order 25(7)(b) to (d) are added to the resolution. Specific quorum provisions should now be unnecessary, the quorum for committees and subcommittees being provided for by standing order 29.

The number of senators on select committees has varied between five and nine. On six- or eight-member select committees, which were once the norm, the chair was usually a government party senator with the ability to exercise a casting vote, giving the government party an effective majority. The use of an odd number membership formula tends, on the other hand, to give the balance of power on committees to minority groups who hold the balance of power in the Senate. The balance of power on a select committee is significant only when the issues under consideration are contentious and divisive. The five-member Select Committee on Public Interest Whistleblowing in 1994, for example, with two government, two opposition and one minority party senator, reported unanimously on a very sensitive issue without dividing along party lines.

Until 1994 select committee chairs were usually government senators. Exceptions were those select committees to which the government of the day failed to nominate members, leaving the chair by default to the opposition. In 1982, the independent Senator Harradine chaired the seven-member Select Committee on Industrial Relations Legislation and in 1983 Senator Peter Rae, who had been the chair of the Finance and Government Operations Committee before the change of government that year, chaired the Select Committee on Statutory Authority Financing, which was appointed to complete an inquiry begun by the standing committee under Senator Rae's chairmanship. Whereas the resolution appointing the Select Committee on Industrial Relations Legislation provided for the chair to be elected from the members of the committee, the resolution appointing the Select Committee on Statutory Authority Financing named Senator Rae as chair of the committee. The chair of the Select Committee on Superannuation and Financial Services was appointed by the Senate in 1999. In 1992 Australian Democrat Senator Coulter was elected chair of the Select Committee on the Functions, Powers and Operation of the Australian Loan Council. In 1993, opposition chairs were elected to the select committees on Public Interest Whistleblowing, and Certain Foreign Ownership Decisions in relation to the Print Media. Also in that year, in anticipation of the government chair of the Select Committee on Superannuation standing down from the position, a resolution was agreed to by the Senate providing for his successor and the deputy chair of the committee to be “allocated among the members of the committee by agreement between the Leader of the Government in the Senate and the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate and the Leader of the Australian Democrats, and, in the absence of agreement duly notified to the President, the allocation of the chair and deputy chair shall be determined by the Senate”. In the event, determination by the Senate was unnecessary as the Leaders agreed that the new chair should be an opposition senator who had previously been deputy chair of the committee. In 1995 the committees on ABC Management, Aircraft Noise, the Land Fund Bill and Land Fund Matters all had non-government chairs. The Select Committee on the Victorian Casino Inquiry, appointed in 1996, had a non-government majority and elected an opposition senator as chair. Six select committees established in 2008, on agriculture and related industries, state government financial management, housing affordability, regional and remote indigenous communities, fuel and energy and the national broadband network, had non-government majorities and Opposition chairs.

Following the adoption of recommendations in the Procedure Committee's First Report of 1994, the sharing of select committee chairs and deputy chairs became a standard practice, reflecting formal arrangements for the sharing of standing committee chairs and deputy chairs.

Since the restructuring of the committee system in 1994, there has been an unofficial agreement about the number of select committees in operation at any one time. Though non-binding, the agreement was reiterated in 2009 when the committee structure returned to the 1994 arrangements.

In acknowledgement of this informal understanding, the Select Committee on the Reform of the Australian Federation was established on 17 March 2010 to be appointed at the conclusion of the Select Committee on the National Broadband Network (which presented its final report on 17 June 2010).

[update: Despite these “unofficial agreements” and “informal understandings”, there were 11 select committees operating concurrently as at 30 June 2020, including eight Senate select committees and three joint select committees, in addition to the Senate’s usual complement.]

Joint committees

Joint committees are committees consisting of members of both Houses appointed by both Houses. They are established where it is considered that matters should be the subject of simultaneous inquiry by both Houses.