Chapter 21

Relations with the House of Representatives

In a bicameral system the conduct of relations between the two houses of the legislature is of considerable significance, particularly as the houses must reach full agreement on proposed legislation before it can go forward into law, and action on other matters also depends on the houses coming to agreement.

The Constitution contains some provisions regulating relations between the Houses:

- section 53 provides some rules relating to proceedings on legislation

- section 57 provides for the resolution of certain disagreements between the Houses in relation to proposed legislation by simultaneous dissolutions of the Houses.

The rules contained in section 53 are dealt with in Chapter 12, Legislation, and Chapter 13, Financial Legislation. Simultaneous dissolutions under section 57 are dealt with in this chapter.

The standing orders of the Senate provide more detailed rules for the conduct of relations between the Houses, particularly in relation to legislation. In so far as these rules regulate relations between the Houses generally, they are also dealt with in this chapter, and in so far as they relate to legislation they are dealt with in more detail in chapters 12 and 13.

Communications between the two Houses

Senate standing orders are concerned only with formal communications between the Houses, as distinct from the many private communications and consultations between members and office-holders of the Houses. The latter, while indispensable to the efficient and orderly conduct of parliamentary proceedings, are of course not regulated by formal rules.

Communications with the House of Representatives may be by:

- message

- conference

- committees conferring with each other.

The most common form of communication is by message. Conferences are treated below. For committees conferring with each other, see Chapter 16, Committees. A committee of the Senate may confer with a committee of the House of Representatives only by order of the Senate.

Messages

Messages between the two Houses may deal with:

- transmission of bills for concurrence, return of bills with or without amendment, and other proceedings in connection with the consideration of bills

- requests for the attendance of members or officers of the other House as witnesses to be examined by the House or a committee

- appointment of joint committees, appointment of members of such committees, and changes in membership

- requests for conferences (see under Conferences, below)

- transmission of resolutions for concurrence.

A message from the Senate to the House of Representatives is in writing, is signed by the President or Deputy President, and is delivered by a clerk at the table or the Usher of the Black Rod.

If the House of Representatives is sitting, a message is delivered to the House and received by the Deputy Clerk or Sergeant-at-Arms. If the House is not sitting, the message is delivered to the Clerk of the House.

Most messages, for example messages with respect to proceedings on bills, pass automatically between the Houses, under provisions in the standing orders. A motion may be moved at any time without notice that any resolution of the Senate be communicated by message to the House of Representatives. This procedure is used where the agreement of the House to a resolution is sought, or it is thought appropriate to advise the House of a resolution of the Senate.

A motion that a resolution of the Senate be communicated by message to the House may be moved by any senator, and not necessarily the senator who moved the motion for the resolution.

A message from the House of Representatives is received, if the Senate is sitting, by a clerk at the table, and if the Senate is not sitting, by the Clerk of the Senate, and is reported by the President as early as convenient, and a future time is normally fixed for its consideration; or it may, by leave, be dealt with at once.

A message is reported to the Senate by the President at any stage when other business is not before the Senate. By convention, however, a message from the House concerning government business is handed to the President by the Clerk when a minister indicates that the government is ready for the message to be reported.

The general rule, that when a message has been reported a future time is fixed for its consideration, and it may be dealt with at once only by leave, does not apply to messages with respect to bills, for which special provision is made.

An unusual situation arose in 1912, when a motion for fixing the time for consideration of a message from the House of Representatives was negatived. The message requested the concurrence of the Senate in a resolution agreed to by the House favouring the formation of two new states out of the territory known as Northern and Central Queensland. Motion was made that the message be taken into consideration on the next day of sitting, but the motion was negatived. As the Senate did not further sit during that session, the message was not again brought up. The effect of the Senate's action was that it declined to consider the message. On many occasions the Senate has not returned to the consideration of a message when a future time (usually the next day of sitting) has been fixed for its consideration, because the order of the day for consideration of the message has not been reached.

Conferences

Conferences between the two Houses provide a means of seeking agreement on a bill or other matter when the procedure of exchanging messages fails or is otherwise inadequate to promote a full understanding and agreement on the issues involved.

In the history of the Commonwealth Parliament, there have been only two formal conferences, and those were in connection with disagreements between the Houses on amendments to bills. It is quite competent for the Houses to agree to conferences on other matters, however. The first conference proposed in the Commonwealth Parliament was to consider the question of the selection of a site for the federal capital. The House of Representatives, requesting the conference in 1903, proposed that such conference consist of all members of both Houses, but the conference was refused by the Senate.

As far as conferences on bills are concerned, the standing orders of the Senate prescribe the stage at which the Senate may request a conference. That stage, pursuant to standing order 127(1), is reached when agreement cannot be achieved, by an exchange of messages, with respect to amendments to Senate bills. There is no provision in the standing orders for a request by the Senate for a conference on a bill originating in the House of Representatives.

The following conferences have been held between the Senate and the House of Representatives:

- Appropriation Bill 1921-22. Disagreement between the Houses on Senate's request for amendments; an informal conference of representatives of both Houses considered the matter in disagreement, namely, whether the salaries of the Clerks of the Houses should be uniform; conference recommended uniformity, and recommendation endorsed by the Houses.

- Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Bill 1930 (HR bill). Conference agreed to, at request of House of Representatives, on amendments in dispute.

- Northern Territory (Administration) Bill 1931 (HR bill). Conference agreed to, at request of House of Representatives, on amendments in dispute.

In each of these cases the conference was successful, agreement being reached by the managers and, following their report, by the Houses.

The standing orders provide general rules relating to conferences, which are applicable to conferences on other matters as well as conferences on bills.

Conferences sought by the Senate with the House of Representatives are requested by messages. In one instance only has the Senate requested a conference with the House of Representatives, in relation to the Social Services Consolidation Bill 1950. The House of Representatives having insisted on an amendment to the bill to which the Senate insisted on disagreeing, a conference was requested with the House of Representatives on the amendment. The House of Representatives, however, did not agree to the request of the Senate for a conference, and desired the reconsideration of the bill by the Senate in respect of the amendment. The Senate subsequently agreed to the amendment insisted on by the House of Representatives.

In requesting a conference, the message from the Senate states, in general terms, the object for which the conference is sought and the number of managers proposed, which is not less than five.

A motion requesting a conference contains the names of the senators proposed by the mover to be the managers for the Senate. If, on such motion, any senator so requires, the managers for the Senate are selected by ballot.

During a conference the sitting of the Senate is suspended. For precedent, see the conference in connection with Northern Territory (Administration) Bill 1931. The time having arrived for the holding of the conference, the sitting of the Senate was suspended until such time as the conference between the Houses should be concluded. When the conference was ready to report, the bells were rung and the sitting resumed.

Before the Senate suspended for this conference, a point of order was taken on whether a conference could take place except during a suspension of the sittings. President Kingsmill held that, while it was unusual for a conference to sit when the House has adjourned, he did not think that there was anything in the standing orders of the Senate to forbid, or even to imply, that a conference may not take place when the Senate has adjourned.

A conference may not be requested by the Senate on any bill or motion of which the House of Representatives is at the time in possession. The rationale of this rule is that a conference should be held only if the Senate is notified of a disagreement between the Houses on a measure.

The managers to represent the Senate in a conference requested by the House of Representatives must consist of the same number of members as those of the House of Representatives (SO 157(3)).

The conferences on the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Bill 1930 and the Northern Territory (Administration) Bill 1931 both consisted of five managers for the Senate and five managers for the House of Representatives.

In a conference between the Houses, if managers appointed by the Senate decline to act, they should be replaced by others. It has been held that there is no means of compelling any senator to act on a conference.

In respect of any conference requested by the House of Representatives the time and place for holding the conference is appointed by the Senate; and when the Senate requests a conference, it agrees to its being held at such time and place as appointed by the House of Representatives, and such agreement is communicated by message. At conferences requested by the House of Representatives the managers for the Senate assemble at the time and place appointed, and receive the managers of the House of Representatives.

At conferences the reasons or resolutions of the Senate, to be communicated by the managers, are in writing; and the managers may not receive any such communication from the managers for the House of Representatives unless it is in writing. The managers for the Senate read the reasons or resolutions to be communicated, deliver them to the managers for the House of Representatives, or hear and receive from the managers for the House the reasons or resolutions communicated by the latter; after which the managers for the Senate are at liberty to confer freely with the managers for the House of Representatives. That is to say, after the preliminary exchange of formalities, a “free” conference is held, at which debate is permissible.

The managers for the Senate, when the conference has terminated, report their proceedings to the Senate. In the case of the two precedents referred to, the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Bill 1930 and the Northern Territory (Administration) Bill 1931, the bill was, in each case, in possession of the Senate at the time of the conference. On presentation of the report of the conference, motion was made that the report be adopted and taken into consideration in conjunction with the message of the House of Representatives (returning the Bill and requesting the conference) in committee of the whole.

The adoption of the report of a conference does not necessarily bind the Senate to the proposals of the conference, which, with reference to amendments in a bill, come up for consideration in committee of the whole.

There must be only one conference on any bill or other matter. In so providing, the Senate profited from the experience of the South Australian Parliament, where it was found that a number of conferences served no good purpose, because the representatives of both Houses always put off coming to a final decision until the last conference.

The main reason for conferences falling into disuse is the rigidity of ministerial control over the House of Representatives. It is more efficient for senators involved with legislation to negotiate directly with the ministers who control what the House does with the legislation.

Simultaneous dissolutions of the Houses

Constitutional provisions and their application

When the Constitution of the Commonwealth was in preparation, one of the major issues in contention was a provision for resolving deadlocks between the Houses of Parliament over legislation. Few constitutions extant at the time contained any such mechanism: those which did mainly provided for conferences between the Houses, reflecting practice as it had developed in the Congress of the United States. The addition of members to unelected upper Houses such as the House of Lords and the NSW Legislative Council was the solution to deadlocks in those jurisdictions. Only with the enactment of the Parliament Act 1911 did the United Kingdom establish a formal framework for resolving a deadlock between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, reflecting the unelected character of the latter house. A solution in NSW took much longer. Canada's national parliament, now the only bicameral legislature in that country, still does not have a comparable procedure.

The South Australian Legislative Council was unique among the colonies in having both an elected upper house and a constitutional provision for the dissolution of the Council, along with the House of Assembly, in cases of legislative deadlock. At the time of the constitutional conventions, however, those provisions, enacted in 1881, had not been used and the South Australian Houses relied on conferences to resolve disagreements, as they do to this day. At the conventions, various deadlock provisions were proposed and rejected including, in 1891, a joint sitting for disagreements about money bills. From the Sydney session of the 1897-98 convention emerged two proposals, influenced by the South Australian provisions: first, for the consecutive dissolution of both Houses; and, secondly, for simultaneous dissolution followed if necessary by a joint sitting at which a three-fifths majority would be required to pass the disputed legislation. It was the latter proposal, as modified following intervention by NSW after its first failed referendum to adopt the Constitution Bill, which was the basis of section 57.

The innovative character of section 57 in constitutional and bicameral practice came from the combination of the possibility of dissolution of, and general election for, both Houses and the ensuing joint sitting, if required.

The provisions in section 57 were intended to be more than a mechanism for resolving deadlocks. They were to be a concession of federalism to democracy. Provided that the whole process set out in section 57 is followed, the normal double majority for the passage of laws would be dispensed with, only for the legislation causing the deadlock, and laws could be passed in accordance with the wishes of the majority of the representatives of the people as a whole, if that majority were not too narrow. In cases of significant disagreement, democratic representation was to prevail over the geographically distributed representation of the people provided by the Senate. (But see Chapter 1 for the point that the House of Representatives is now usually controlled by the executive government and may not in fact reflect in its composition the votes of the majority of the electors.) It is sometimes said that the purpose of section 57 is to enable the government or the House of Representatives to prevail over the Senate. This interpretation, however, was explicitly rejected by the High Court.

Laws have been passed in this way only once, in 1974, when there occurred the only double dissolution followed by a joint sitting of the Houses.

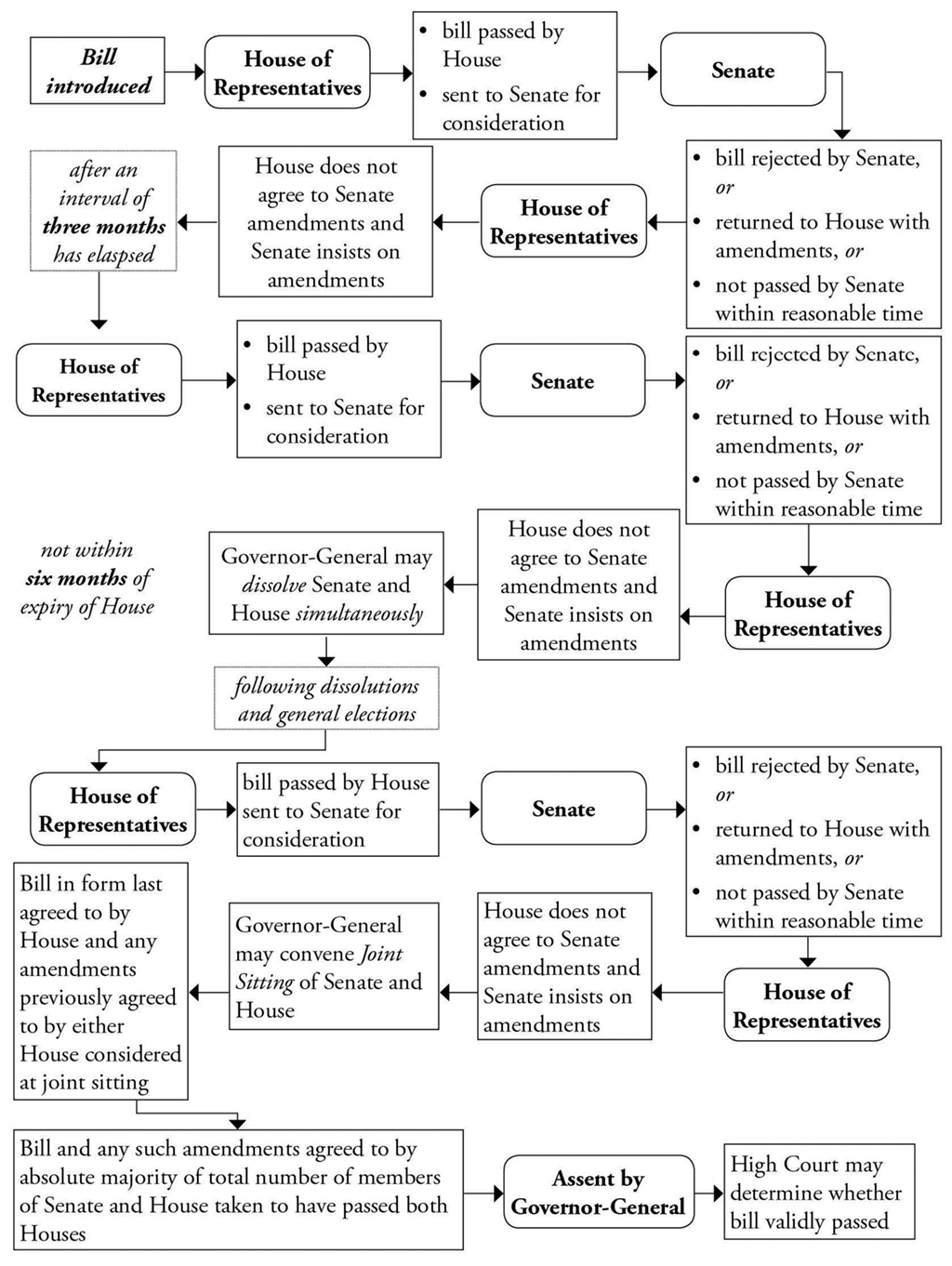

Section 57 of the Constitution as it relates to simultaneous dissolutions provides:

If the House of Representatives passes any proposed law, and the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree, and if after an interval of three months the House of Representatives, in the same or the next session, again passes the proposed law with or without any amendments which have been made, suggested, or agreed to by the Senate, and the Senate rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree, the Governor-General may dissolve the Senate and the House of Representatives simultaneously. But such dissolution shall not take place within six months before the date of the expiry of the House of Representatives by effluxion of time.

Since federation, section 57 has been activated on seven occasions — 1914, 1951, 1974, 1975, 1983, 1987 and 2016 — to resolve deadlocks over legislation between the Houses. On four occasions the government advising simultaneous dissolutions has been returned to office; on only one of those occasions, 1974, did the legislation leading to the dissolutions become law, and, in that instance, after a joint sitting as provided for in paragraphs 2 and 3 of section 57. In 1951, the Menzies Government, while not reintroducing the banking legislation which was the subject of the simultaneous dissolutions, nonetheless proceeded with other legislation of similar character. The Hawke Government abandoned the single bill on which it had secured a simultaneous dissolution in 1987 when a majority of the Senate in effect declared that it would disallow regulations made under the legislation to bring it into operation.

The simultaneous dissolutions of 1914 and 1983 saw the defeat of the government advising the dissolutions. The legislation on which the dissolution was based was, in all cases, dropped. In 1975, the simultaneous dissolutions were based on 22 proposed laws of the ousted Whitlam Government. The caretaker Fraser Government, however, secured majorities in both Houses so no further action was taken.

As a consequence of the seven simultaneous dissolutions, and the judgments of the High Court in the three cases arising from the 1974 dissolutions, it is now possible to amplify the workings of section 57 of the Constitution so far as simultaneous dissolutions of the two Houses are concerned. The following observations can be advanced as influencing the activation of section 57.

The provisions of section 57 are mandatory, not directory in respect of the validity of legislation. Failure to comply with them therefore results in invalidity of any enactment which does not conform to its stipulations. However, even failure to observe the provisions of section 57 would not invalidate dissolutions of the two Houses.

The interval of three months referred to in paragraph 1 of section 57 is measured from the Senate's rejection or failure to pass a bill. According to the High Court, it is “measured not from the first passage of a proposed law by the House of Representatives, but from the Senate's rejection or failure to pass it. This interpretation follows both from the language of section 57 and its purpose which is to provide time for the reconciliation of the differences between the Houses; the time therefore does not begin to run until the deadlock occurs”.

A prorogation of Parliament does not have the effect of negating earlier events which qualified bills as proposed laws in respect of which a double dissolution could be granted. Simultaneous dissolutions may be granted in respect of bills which qualified under section 57 in an earlier session.

-

Simultaneous dissolutions have been granted on several occasions where the proposed legislation has been deemed to have “failed to pass” the Senate. In 1951, following the second passage of the Commonwealth Bank Bill through the House, the Senate, after second reading debate extending over several days, referred it to a select committee. This was said by Prime Minister Menzies to constitute “failure to pass”, a phrase which encompassed “delay in passing the bill” or “such a delaying intention as would amount to an expression of unwillingness to pass it”. The Attorney-General, Senator J.A. Spicer, wrote that the phrase, “failure to pass”, was intended to deal with procrastination. Professor K.H. Bailey, the Solicitor-General, considered, inter alia, that “adoption of Parliamentary procedures for the purpose of avoiding the formal registering of the Senate's clear disagreement with a bill may constitute a 'failure to pass' it within the meaning of the section”.

The Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the House of Representatives, Dr H.V. Evatt, had previously been reported in the press as saying that referral of legislation to a select committee, being clearly provided for in the standing orders of the Senate, was not a failure to pass. (See below.)

In 1975, the High Court held that the proposed law creating the Petroleum and Minerals Authority had not, as claimed, “failed to pass” the Senate on 13 December 1973 and, as a result, it was declared not to be a valid law of the Commonwealth. The second reading was, in fact, negatived a first time in the Senate on 2 April 1974. In its judgment, the High Court held that “The Senate has a duty to properly consider all Bills and cannot be said to have failed to pass a Bill because it was not passed at the first available opportunity; a reasonable time must be allowed”. In so deciding, the majority observed that the opinions of individual members of either House “are irrelevant to the question of whether the Senate's action amounted to a failure to pass”.

In 1983 nine proposed laws dealing with sales tax were deemed to have “failed to pass” the Senate after being first passed by the House of Representatives. These bills, being legislation which under section 53 the Senate could not amend but only suggest amendments, were in the possession of the House of Representatives prior to being discharged from its notice paper, the Senate having decided to press requests. As the government was defeated in the election it is not possible to affirm conclusively that the Senate had, in these circumstances, “failed to pass” the bills. It might be argued that pressed requests refused by the House are analogous to amendments to a bill by the Senate which are unacceptable to the House of Representatives and thus bring the proposed legislation within the ambit of section 57, but this argument was not advanced.

It is not necessary for the Houses to be dissolved without delay once the conditions of section 57 have been met. According to the High Court,

This interpretation follows both from the language of s. 57, which provides for express time limits in relation to other parts of the procedure laid down by the section but provides for none in respect to the interval between the Senate's second rejection of a proposed law and the double dissolution...

Inter alia, the Court observed that “'undue delay' would be impossible of determination by the court”. In the case in question, Chief Justice Barwick (in minority) contended that “there is a temporal limitation which requires that the second rejection by the Senate and the double dissolution must be so related in time as to form part of the current disagreements between the Houses”. However, the lapse of time in this instance, a maximum of seven and a half months, was not sufficient to disqualify them as grounds for simultaneous dissolutions.

-

Not only is it not necessary for simultaneous dissolutions to follow a second rejection etc. by the Senate “without undue delay”, it is not usual for account to be taken of the currency of legislation when it is submitted as a basis for simultaneous dissolutions. Thus, in 1983, Governor-General Stephen simply noted that “in the case of each of these measures a considerable time has passed since they were rejected or not passed a second time in the Senate”.

-

There is no limit to the number of proposed laws on which simultaneous dissolutions of the Houses may be based. The first dissolutions based on more than one bill occurred in 1974 (subsequently in 1975, 1983 and 2016). In 1974 the Attorney-General (Senator Lionel Murphy, QC) and the Solicitor-General (M.H. Byers, QC) advised the Governor-General in a joint opinion that:

The words of the paragraph [one of section 57], in our view, clearly indicate that the power to dissolve is exercisable when more than one proposed law has been dealt with in the required manner. ... Our view does not require nor involve that the words “any proposed law” are read as comprising a plural. We do not, of course, suggest that so to read them would be to depart from recognised canons of construction. What we have said above but treats the words of condition as operating successively and singularly upon each such law.

This view, when challenged, was upheld by the High Court: “... a joint sitting of both Houses of Parliament convened under s. 57 may deliberate and vote upon any number of proposed laws in respect of which the requirements of s. 57 have been fulfilled.” As Justice Stephen observed: “One instance of double rejection suffices but if there be more than one it merely means that there is a multiplicity of grounds for a double dissolution, rather than grounds for a multiplicity of double dissolutions”.

The political or policy significance of legislation is not material to a decision to accede to a request that both Houses be simultaneously dissolved. This issue arose in 1914. The Opposition in the Senate, which contested the Governor-General's decision to grant simultaneous dissolutions, protested that the proposed legislation, the Government Preference Prohibition Bill, was not a vital measure and that the deadlock had been contrived. That the deadlock was contrived in a narrow sense cannot be disputed for this is clearly set out in a memorandum furnished to the Governor-General by Prime Minister Joseph Cook which stated that when it became “abundantly clear” that the Opposition had taken control of the Senate, “we [the Government] decided that a further appeal to the people should be made by means of a double dissolution, and accordingly set about forcing through the two short measures for the purpose of fulfilling the terms of the Constitution”.

An address to the Governor-General carried by the Senate on motion of the Opposition Labor Party stated that the Senate's powers would be “reduced to a nullity” were it possible to secure a dissolution on legislation which contained “no vital principle” or gave “effect to no reform”.

It has been customary subsequently for prime ministers, when proposing simultaneous dissolutions, to stress the significance of the legislation involved. Thus, in 1951, Prime Minister Menzies referred to the Commonwealth Bank Bill and other proposed laws about which there was dispute between the Senate and the House as “major legislative measures”; in 1974, Prime Minister Whitlam informed the Governor-General that “the Senate has twice rejected, failed to pass or unacceptably amended several proposed laws which are integral parts of the Government's program of reform and development”, and, later, “the six proposed laws are all of importance to the Government”; in 1983, Prime Minister Fraser based advice about simultaneous dissolutions on 13 proposed laws “of importance to the Government's budgetary, education and welfare policies ...”; four years later Prime Minister Hawke declared that the Australia Card Bill 1986 was “an integral part of the Government's tax reform package and is aimed at restoring fairness to the Australian taxation and social welfare systems”. In a similar vein, in 2016, Prime Minister Turnball advised that the deadlocked bills “represent important elements of the Government's economic plan for jobs and growth, and of its reform agenda” and elaborated on the objectives of each of the bills.

Except in 1983 (up to a point), governors-general have refrained from comment about the significance of the legislation. In 1983, Governor-General Stephen wrote that on the basis of precedents he should inter alia “pay regard to the importance of the measures in question”. In the event, however, he disclaimed ability so to do: “... I am not myself in any position, from their mere subject matter and text, to form a view about the particular importance of any of them”.

Even where the conditions for simultaneous dissolutions as prescribed in section 57 have been met, it is customary for advice to be provided to the Governor-General on the “workability of Parliament”. The issue of the workability of the Parliament was addressed in the granting of the 1914 simultaneous dissolutions. Prime Minister Cook claimed that the Liberal Government was hindered in the Senate but that the Opposition Labor Party would not be able to “carry on for a single hour in the House of Representatives”. The caucus practices of Labor made compromise impossible. Moreover, a dissolution of the House of Representatives alone would not necessarily resolve the situation: “... however large the Liberal majority in the House of Representatives might be as a result of an election, it would have the same Senate as at present”.

In 1951, Prime Minister Menzies observed that in discussions about the 1914 simultaneous dissolution “... some importance appears to have been attached to the unworkable condition of the Parliament as a whole”. He went on to state that “the present position in the Commonwealth Parliament is such that good government, secure administration, and the reasonably speedy enactment of a legislative program are being made extremely difficult, if not actually impossible”.

In 1974, Prime Minister Whitlam wrote that “the Senate has delayed and obstructed the program on the basis of which the Government was elected to office in December 1972”. Nine years later, Prime Minister Fraser stated that he regarded “a double dissolution as critical to the workings of the government and of the Parliament ... some significant Government legislation was not passed by the Senate. There are measures that we have not even put to the Parliament because we know that they would not achieve passage through the Senate”.

In 1987 Prime Minister Hawke advised: “In summary, I regard the situation which has arisen in the Parliament as critical to the workings of the Government and the Parliament. The Senate has been spending large amounts of time debating matters of marginal significance, with the effect of reducing substantially the time available for proper consideration of essential government legislation. The imposition of artificial deadlines by the Senate on receipt of government bills for passage has exacerbated this problem. Just today the Senate has refused to reconsider the Government's legislation to extend television services to rural areas.”

In contrast, in 2016, Prime Minister Turnbull was silent on the workability of the Parliament (which at that point was only days away from 6 months within the expiration of the House of Representatives by effluxion of time), highlighting instead the longstanding commitment of the Government parties to the bills since before the 2013 election, and that the Government had “sought to secure passage of the Bills throughout the life of this Parliament”. Governor-General Cosgrove accepted the advice without comment, other than to note the Prime Minister's assurances that there was sufficient Supply for the ordinary services of government.

Argument about the workability of the Parliament is sometimes joined by argument about the importance of decisions to be made in the future. Prime Minister Cook said that “It has been apparent to all that the Federal Parliament will shortly be faced with the most serious financial difficulty which has yet come before it”.

The 1983 advice included the following observation:

It is of paramount importance in facing the difficult economic circumstances that lie ahead that the Government knows that it has the full confidence of the Australian people and that the Australian people have full confidence in its Government's ability to point the way towards recovery. I regard this as of such paramount importance that on this issue alone I believe that I am justified in asking Your Excellency to dissolve the Parliament and issue writs for a general election in both Houses.

Governor-General Munro-Ferguson, in 1914, responded simply that he had decided to accede to the Prime Minister's request “having considered the parliamentary situation”.

Governor-General Hasluck refused to be drawn in 1974: as it was clear that the grounds for granting simultaneous dissolutions were provided by the parliamentary history of the six nominated bills, it was “not necessary for [him] to reach any judgment on the wider case [the Prime Minister had] presented that the policies of the Government have been obstructed by the Senate”. He concluded: “It seems to me that this is a matter for judgment by the electors”.

The simultaneous dissolutions of 1975, whilst not providing opportunity for advice in the usual manner, nevertheless disclosed the views of the Governor-General in authorising simultaneous dissolutions on that occasion. The election itself was brought on by the Prime Minister's inability to secure passage of appropriation legislation through the Senate. The Governor-General decided that “the appropriate means is a dissolution of the Parliament and an election for both Houses”.

Governor-General Kerr, in his 'Detailed Statement of Decisions', specifically rejected use of a periodical election for the Senate (due by 30 June 1976) as a possible resolution of the deadlock because it would “not guarantee a prompt or sufficiently clear prospect of the deadlock being resolved in accordance with proper principles”. The treatment of this possibility in this instance is not dissimilar to that of Prime Minister Cook's review of possible solutions to the situation faced by his Government.

Governor-General Stephen adopted a different view in 1983. In considering the Prime Minister's advice he decided, on the basis of “such precedents as exist”, that he should, inter alia, “pay regard ... to the workability of Parliament”; and it was on this “score” that he sought further advice from the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister's counsel was unambiguous: “Clearly, there is a need for the Government, in the critical period we face, to have decisive control over both Houses of Parliament”.

-

The process of enacting legislation by joint sitting following simultaneous dissolutions may be the subject of review by the High Court to ensure compliance with the terms of section 57.

In 1974 legislation of the Whitlam Government creating a Petroleum and Minerals Authority was held by the High Court to be invalid on the ground that its enactment did not comply with the requirements of section 57. In particular, the Court held that the provision for an interval of three months between first rejection by the Senate and second passage by the House of Representatives had not been observed. In so deciding, the Court determined that the fact that the Senate had not passed the bill on 13 December 1973, the day on which it was received from the House of Representatives, did not constitute a failure to pass.

Among the findings of the Court on this matter were the following:

- The Court has jurisdiction to intervene at any stage in the special process provided by s. 57 to restrain excesses of constitutional authority, but it should not do so before a proposed law is passed by a joint sitting in any case where the proposed law can be declared invalid if s. 57 has not been complied with.

- The provisions of s. 57 are not concerned with internal parliamentary procedure but constitute conditions of law-making; the principle that courts may not examine the law-making process has no application where a legislature is established and governed by an instrument which prescribes that certain laws may only be passed in a particular way.

- The question of whether there was any failure to comply with the provisions of s. 57 is justiciable.

-

Amendments may be included in a bill on its second presentation. Section 57 allows a bill submitted to the Senate for a second time to include “any amendments which have been made, suggested, or agreed to by the Senate”. This provision has not been subjected to judicial analysis. For the question of amendments which may be submitted to a joint sitting, see below under Joint sittings of the Houses. If the Senate were to agree to amendments to a bill but reject it at the third reading, it may be doubted whether those amendments could be included in the bill on its second presentation. For a bill resubmitted to the Senate after a three month interval with amendments made by the Senate, see the Land Fund and Indigenous Land Corporation (ATSIC Amendment) Bill 1995.

-

A disagreement between the Houses over amendments probably requires more than a single rejection of Senate amendments by the government to satisfy the requirements of section 57.

In Victoria v Commonwealth (1975) 134 CLR 81, the Chief Justice made the following observation:

The expression in s 57 is “passes with amendments with which the House of Representatives will not agree”. Those words would not, in my opinion and with due respect to a contrary opinion attributed to Sir Kenneth Bailey, necessarily be satisfied by the amendments made in the first place by the Senate. At the least, the attitude of the House of Representatives to the amendments must be decided and, I would think, must be made known before the interval of three months could begin. But the House of Representatives, having indicated in messages to the Senate why it will not agree, may of course find that the Senate concurs in its view so expressed, or there may be some modification thereafter of the amendments made by the Senate which in due course may be acceptable to the House of Representatives. It cannot be said, in my opinion, that there are amendments to which the House of Representatives will not agree until the processes which parliamentary procedure provides have been explored.

Although the question was not decided by the Court, it is reasonable to conclude that there is not a disagreement over amendments within the terms of section 57 until the House has disagreed with Senate amendments and the Senate has had an opportunity, by the return of the bill to the Senate, to decide whether it insists on its amendments.

In 1997-98 the government claimed that the conditions of section 57 had been met in respect of the Native Title Amendment Bill 1997 by the government rejecting some Senate amendments in the House and immediately laying the bill aside without returning it to the Senate. This claim was disputed by advices provided to senators by the Clerk of the Senate. As the government did not proceed to simultaneous dissolutions on the basis of this bill, there was no opportunity for this question to be judicially answered. The view then taken seems to have been abandoned in the case of the Workplace Relations Amendment (Fair Dismissal) Bill 2002 [No. 2], which made a further journey between the Houses after the Senate had already once insisted on its amendments.

On occasions the government in the Senate has voted against the third readings of its own bills, apparently to express disapproval or rejection of amendments made by the Senate to the bills. If those bills had been rejected at the third reading, the government could not have claimed that there was a disagreement between the Houses over amendments, because the House of Representatives would not have considered the amendments. It would also be difficult to argue that the Senate had rejected or failed to pass the bills when the government had voted against them.

Simultaneous dissolutions of 1914

Following the 1913 general election for the House of Representatives and periodical election for the Senate, the new Liberal government under Joseph Cook had a narrow majority in the House (38-37) but was in a significant minority (29-7) in the Senate. These were the circumstances in which the first simultaneous dissolutions of the two Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament occurred the following year.

The occasion for the simultaneous dissolutions was the Government Preference Prohibition Bill. The bill was first passed by the House on 18 November 1913, only to be rejected in the Senate on the second reading on 11 December 1913; in the next session the proposed law was again passed by the House on 28 May 1914 and again rejected by the Senate on the first reading on 28 May 1914.

On 10 June 1914 the Prime Minister informed the House of Representatives that, subject to provision of funds for carrying on the public service during the election period, the Governor-General had granted a double dissolution on the basis of advice that the “Parliament was unworkable, that it was impossible to manage efficiently the public business... .”.

There was debate about the decision to dissolve on the ground that the measure in question was not a national or vital one. The Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Senator G.F. Pearce of Western Australia, contended that simultaneous dissolutions should only occur when the Senate, by its treatment of the financial measures of the Government, rendered government impossible. Pointing to the collocation of section 57, which follows immediately upon those sections of the Constitution dealing with the financial powers of the Houses, Pearce argued that the House of Representatives was specifically mentioned in section 57 because it is there that money bills must originate.

Quick and Garran claim that section 57 may apply to any bill, but Pearce's argument found support in a speech to the Federal Convention by Edmund Barton, Leader of the Convention:

...“deadlock” is not a term which is strictly applicable to any case except that in which the constitutional machine is prevented from properly working. I am in very grave doubt whether the term can be strictly applied to any case except the stoppage of legislative machinery arising out of conflict upon the finances of the country. A stoppage which arises on any matter of ordinary legislation, because the two Houses cannot come to an agreement at first, is not a thing which is properly designated by the term “deadlock” — because the working of the Constitution goes on — the constitutional machine proceeds notwithstanding a disagreement. It is only when the fuel of the machine of government is withheld that the machine of government comes to a stop, and that fuel is money.

Pearce's approach would likewise seem to be supported by the advice of Chief Justice Griffith to the Governor-General. According to Griffith, the power of dissolution should not be exercised simply because the conditions specified in section 57 exist:

It should, on the contrary, be regarded as an extraordinary power, to be exercised only in cases in which the Governor-General is personally satisfied, after independent consideration of the case, either that the proposed law as to which the Houses have differed in opinion is one of such public importance that it should be referred to the electors of the Commonwealth for immediate decision by means of a complete renewal of both Houses, or that there exists such a state of practical deadlock in legislation as can only be ended in that way.

Pearce also observed that the government had not made any attempt to resolve the deadlock by means of a conference between managers of the two Houses.

On 17 June 1914 the Senate agreed to an address to the Governor-General requesting that the correspondence which passed between the Governor-General and his advisers in regard to the double dissolution of the Parliament might be made public. The address stated, inter alia, that:

The decision of Your Excellency appears to be fatal to the principles upon which the Senate has hitherto acted, which, we submit, are in strict accordance with a truly Federal interpretation of the Constitution. The Constitution deliberately created a House in which the States as such may be represented, and clothed this House with co-ordinate powers (save in the origination of Money Bills) with the Lower Chamber of the Legislature. These powers were given to the Senate in order that they might be used; but if a Senate may not reject or even amend any bill because a Government chooses to call it a “test” bill, although such bill contains no vital principle or gives effect to no reform, the powers of the Senate are reduced to a nullity. We submit that no constitutional sanction can be found for that view, which is repugnant to one of the fundamental bases of the Constitution, viz, a Legislature of two Houses, clothed with equal powers, one representing the people as such, the other representing the States. And we respectfully submit that the dissolution of the Senate ought not to follow upon a mere legitimate exercise of its functions under the Constitution, but only upon such action as makes responsible government impossible, e.g. the rejection of a measure embodying a principle of vital importance necessary in the public interest, creating an actual legislative deadlock and preventing legislation upon which the Ministry was returned to power. These conditions do not exist in the present case.

The Address also stated that there was not a deadlock between the Houses, referring to the following statement:

SESSION 1913

Bills passed and assented to 23

Bills passed by Senate only 6

Bills passed by Senate without amendment 18

Bills passed by Senate with amendments 5

Amendments disagreed with (Bills laid aside by House of Representatives) 3*

Bills rejected by Senate 2

* Including Committee of Public Accounts Bill No. 1

The Governor-General declined to respond to the Senate's request. He stated, however, that the grounds for the decision were to be found in the Prime Minister's statement, made with his permission, to the House of Representatives.

The Parliament was dissolved on 30 July 1914. At the election on 5 September 1914, the Labor Party led by Andrew Fisher won 42 seats in the House of Representatives against 32 by the Liberal Party, with one Independent; the result in the Senate was: Labor, 31; Liberal, 5.

The correspondence relating to the dissolutions was tabled in both Houses on 8 October 1914.

Simultaneous dissolutions of 1951

The general election for the House of Representatives and the periodical election for the Senate held on 10 December 1949 were notable in that they were the first to be held following enlargement of the Parliament in 1948 for the first time since the formation of the Commonwealth, and since adoption of the proportional/preferential method of electing the Senate. The election brought the Menzies Liberal-Country Party Government to office with a majority in the House (74-48, with one independent) but, partly as a result of the as yet uncompleted transition from the old method of election, in a minority in the Senate (34-26).

Soon after the Parliament assembled in 1950 it became obvious that there would be serious disagreements between the Houses. These were ultimately resolved at a double dissolution election on 28 April 1951 based on the Commonwealth Bank Bill. While the Government's House majority was slightly reduced (69-54), the Senate position was reversed and it now had a majority of 4 (32-28).

The proposed legislation which formed the basis of the double dissolution was the Commonwealth Bank Bill.

In initial consideration of the proposed legislation, the bill was read a third time in the House of Representatives on 4 May 1950 and received by the Senate on 10 May 1950. After amendment, it was read a third time by the Senate on 21 June 1950. The next day the House disagreed with the amendments of the Senate; the Senate insisted on the amendments which were again rejected by the House on 23 June 1950. The Senate reaffirmed its insistence on the amendments on 10 October. The bill was returned to the House which ordered that the Senate's message be taken into consideration at the next sitting. The matter was, however, put on the bottom of the House notice paper and was still there when Parliament adjourned on 8 December 1950.

Meanwhile, on 4 October 1950, an identical bill, the Commonwealth Bank Bill (No. 2) was introduced in the House of Representatives, was read a third time a week later, and was received by the Senate on 12 October 1950.

The battle over the bill resumed the following year when, on Monday evening 12 March 1951, the Leader of the Government in the Senate, Senator O'Sullivan, ordered a reprint of the Senate notice paper in order to bring the Commonwealth Bank Bill (No. 2) to the top of the business paper. When the Senate met on 13 March 1951 it proceeded with consideration of the bill.

The same evening, in the House of Representatives, the Prime Minister challenged the Labor majority in the Senate to reject the measure.

However, following the second reading of the bill late that night, the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, Senator Ashley, successfully moved that the bill be referred to a select committee. The resolution provided that the select committee should report in four weeks. (This course of action had been foreshadowed in Senator Ashley's second reading speech.)

On the basis of advice submitted on Friday 16 March by the Prime Minister, the Governor-General dissolved both Houses on 19 March. In the Proclamation the Governor-General determined that the Senate had “failed to pass” the Commonwealth Bank Bill after it had, on the first occasion, been unacceptably amended.

In addition to the Commonwealth Bank Bill, there was disagreement between the Houses about other legislation. At the time of the winter adjournment the House of Representatives had laid aside the Communist Party Dissolution Bill on the basis that amendments made in the Senate were not acceptable. The bill was again passed by the House. When it reached the Senate, the Government Leader (O'Sullivan) moved unsuccessfully “That the bill be declared an Urgent Bill.” Also unsuccessful was a government attempt to suspend Standing Orders so as to eliminate formal delays in the passage of the legislation. For their part, the Opposition brought on its own bill, the Constitution Alteration (Prices) Bill. It was resolved that this bill should have precedence so long as it remained on the notice paper.

Eventually, following a decision by the National Executive of the Labor Party, it was decided that the Party should not oppose the Communist Party Dissolution Bill in the form submitted to the Senate. The bill was brought forward on 17 October and passed all remaining stages the next day. The legislation was declared invalid by the High Court on 9 March 1951.

Another bill, the Government's Constitution Alteration (Avoidance of Double Dissolution Deadlocks) Bill, was referred to a select committee of the Senate for report.

In the new year, the Labor caucus resolved on 7 March 1951, the day following its introduction, to block government legislation amending the Conciliation and Arbitration Act to provide for secret ballots for the election of union officials.

Other bills which had failed to pass but did not meet the requirements of section 57 were the Social Services Consolidation Bill and the National Service Bill. The latter bill had been referred to a select committee which trenchantly criticised the government for the action of the cabinet in causing a direction to be issued to the Chiefs of Staff and certain other officials not to attend before the committee.

The 1951 double dissolution did not involve rejection of proposed legislation and accordingly gave rise to discussion of the meaning of “fails to pass.” In handling the Commonwealth Bank Bill (No. 2), Prime Minister Menzies stated in advice to the Governor-General that:

... there is clear evidence that the design and intention of the Senate in relation to this bill has been to seek every opportunity for delay, upon the principle that protracted postponement may be in some political circumstances almost as efficacious, though not so dangerous, as straight-out rejection. Since failure to pass it, in section 57, distinguished from rejection or unacceptable amendment, it must refer, among other things, to such a delay in passing the bill or such a delaying intention as would amount to an expression of unwillingness to pass it. Clear evidence emerges from the whole of the history of the legislation in the Senate.

The Prime Minister then outlined decisions of the Senate, made against the vote of the government, which provided “evidentiary value as an indication of the real intentions of the Senate.”

The Prime Minister further observed that when the bill came before the Senate for the second time, the Senate might have given the bill a second reading and immediately referred it to a select committee. Instead, there was another second reading debate “precisely similar” to that which had occurred months before.

The Prime Minister's advice to the Governor-General concluded:

There is no room for doubt that ever since the bill went to the Senate for a second time on October 12th, 1950, no new issues have arisen in relation to it. It is a relatively short bill. Its contentious provisions are clear, have been canvassed in both Houses of Parliament at great length, and have been the subject, as I have shown, of a long series of votes. The appointment of a Select Committee at this extremely late hour is conclusive evidence of an intention to delay the bill, and clearly constitutes a failure to pass it.

The Prime Minister, referring back to the double dissolution of 1914, observed that “some importance appears to have been attached to the unworkable condition of the Parliament as a whole.”

The Attorney-General, Senator Spicer, informed the Prime Minister in advice later put before the Governor-General:

The words “fail to pass” in the section are designed to preclude the Senate, upon being proffered a bill with an opportunity to pass it with or without amendments or to reject it, from declining to take either course, and instead deciding to procrastinate.

In the present circumstances the Senate has had a second opportunity of choosing whether to pass with or without amendments or to reject the proposed law. It has declined to take either course and, unquestionably, has decided to procrastinate. In my opinion, this completely satisfies the words “fail to pass” as properly understood in the section and, in my opinion, the power of the Governor-General to dissolve both Houses has arisen.

Professor K.H. Bailey, the Solicitor-General, stated that:

The addition of the words “fail to pass” is intended to bring the section into operation if the Senate, not approving a bill, adopts procedures designed to avert the taking of either of these definitive decisions on it. The expression “fails to pass” is clearly not the same as the neutral expression “does not pass”, which would perhaps imply mere lapse of time. “Failure to pass” seems to me to involve a suggestion of some breach of duty, some degree of fault, and to import, as a minimum, that the Senate avoids a decision on the bill.

In a recent opinion, Sir Robert Garran enumerated as follows, and in terms which in general I respectfully adopt, the matters to be taken into account in ascertaining the fact of failure or non-failure to pass:

“Mainly, I think, the ordinary practice and procedure of Parliament in dealing with bills; including facts arising out of the unwritten law relating to the system of responsible government: the way in which the Government arranges the order of business and conducts the passage of Government measures through both Houses, and the various ways in which the Opposition seeks to oppose. It will be material to know what opportunities the Government has given for proceeding with the bill, and what steps the Senate has taken to delay or defer consideration.

There are many ways in which the passage of a bill may be prevented or delayed: e.g.

- It may be ordered to be read (say) this day six months.

- It may be referred to a Select Committee.

- The debate may be repeatedly adjourned.

- The bill may be 'filibustered' by unreasonably long discussion, in the House or in Committee.

The first of these would leave no room for doubt. To resolve that a bill be read this day six months is a time-honoured way of shelving it.

The second would be fair ground for suspicion. But all the circumstances would need to be looked at.

The third, if it became systematically employed against the Government, would lead to a strong inference.

But just at what point of time failure to pass could be established, might be hard to determine ...

In the fourth case too, the point at which reasonable discussion is exceeded, and obstruction, as differentiated from honest opposition, begins, would be very hard to determine. But sooner or later, a 'filibuster' can be distinguished from a debate ...”

Section 57 cannot of course be regarded as nullifying the express provision in section 53 that except as provided in that section the Senate should have equal power with the House of Representatives in respect to all proposed laws. But it is equally clear that on the fair construction of section 57 a disagreement between the Houses can be shown just as emphatically by failure to pass a bill as by its rejection or amendment. Perhaps the principle involved can be expressed by saying that the adoption of Parliamentary procedures for the purpose of avoiding the formal registering of the Senate's clear disagreement with a bill may constitute a “failure to pass” it within the meaning of the section.

The double dissolution was criticised on two grounds. Dr H.V. Evatt, MP, Deputy Leader of the Opposition in the House of Representatives and a former Justice of the High Court, claimed that the requirements of section 57 had not been met:

That section stated that there should be an interval of at least three months between the end of the first dispute between the House of Representatives and the Senate and the beginning of the second dispute on the same issue before a double dissolution could be sought on the ground that the legislation had been twice rejected or unacceptably amended.

The second objection was that reference of the bill to a select committee did not constitute failure to pass, such reference being clearly provided for in the standing orders of the Senate and being a legitimate and proper function of the Senate in the consideration of bills.

On 17 October 1951 Senator McKenna, Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, moved that government papers relating to the double dissolution be tabled. In his speech Senator McKenna said that production of the documents would do a great deal to clarify certain constitutional issues involved: Whether the period of three months which must elapse before the same bill is again presented commences from the beginning of the dispute between the two Houses, or from the end of the first dispute between the two Houses; in what circumstances apart from outright rejection of a measure, or the making of amendments to it which are unacceptable to the House of Representatives, can the Senate be deemed to have failed to pass it; has the Governor-General, under section 57, an absolute discretion either to grant or to refuse a request for a double dissolution, or is he bound to act upon the advice tendered to him by the Ministers of the Crown; and whether the government based any portion of its case upon the general conduct of the Senate apart altogether from the Commonwealth Bank Bill.

The Prime Minister, whilst agreeing to table the documents at “a proper time”, told the House of Representatives that he did not propose to do so “at a time when they would give rise to discussions in which the present occupant of the position of Governor-General would be involved.” The documents were tabled on 24 May 1956.

In a foreword, the Prime Minister offered views which coincide with those of Chief Justice Griffith in his advice to the Governor-General concerning the 1914 double dissolution:

In the course of our discussion, I had made it clear to His Excellency that, in my view, he was not bound to follow my advice in respect of the existence of the conditions of fact set out in section 57, but that he had to be himself satisfied that those conditions of fact were established.

Simultaneous dissolutions of 1974

On 11 April 1974 Governor-General Hasluck simultaneously dissolved the Senate and the House of Representatives, acting upon advice of Prime Minister Whitlam.

This occasion was unusual in several respects. In the first instance, the Prime Minister's advice did not immediately stem from disagreement over legislation but from the decision of the Opposition (Liberal and Country) parties, supported by the Democratic Labor Party in the Senate, to refuse passage of the second reading of appropriation legislation until the government agreed “to submit itself to the judgment of the people” at the same time as the forthcoming periodical election for the Senate which had been set down for 18 May 1974. The specific background to this decision of the Opposition parties was the announcement that Senator Vincent Gair, a former Premier of Queensland and a former Leader of the Democratic Labor Party in the Senate, had accepted an appointment as Australian Ambassador to Ireland.

As Gair's term did not expire until 30 June 1977, his appointment was seen as creating a sixth vacancy in Queensland: there was speculation that the additional vacancy would improve the government's chances of winning a third seat in Queensland and thus improve its chances of securing a majority in the Senate.

Second, while the simultaneous dissolutions of 1914 and 1951 had been granted on the basis of a single bill only, that of 1974 was granted on the basis of six bills believed to meet the terms of section 57 of the Constitution. Subsequently, and again for the first time, one of the bills (following enactment) was challenged in the High Court. The court declared the legislation invalid because the terms of section 57 had not been met.

Finally, the simultaneous elections for the two Houses did not resolve the disagreement and a joint sitting was thus required to consider and enact the legislation upon which the election had been based.

The 1974 general elections for both Houses were the climax of disagreements between the two following the general election of 1972. At that election the ALP secured a majority in the House by winning 68 seats to 58 won by the Opposition parties. It thus formed a government for the first time in 23 years. The party position in the Senate, however, remained as it had been since 1 July 1971: ALP, 26; Liberal, 21; Country Party, 5; Democratic Labor Party, 5; Independents, 3.

From the commencement of the Parliament it was clear that the Senate would continue to be a forum of vigorous scrutiny of the government as it had been especially in the previous half decade. Indeed, in the debate on the Address-in-Reply, Senate Opposition Leader, Senator Withers, reminded the Senate that it had been deliberately created by the founding fathers to act as a check and a balance and that it might well be called upon to protect the national interest by exercising its undoubted constitutional rights and powers.

In considering the background to the simultaneous dissolutions of 1974 it is sensible to distinguish those aspects which relate directly to legislation, and thus potentially fall within the scope of section 57, and other, general proceedings of the Parliament including scrutiny of regulations, statutory rules and the like.

Four bills were postponed. Two, relating to seas and submerged lands, were initially postponed in order to allow the states to consult each other or to make representations to the Commonwealth Government. In postponing consideration of the legislation it was explained that such a course was consistent with the Senate's role as a states assembly and that the step was taken in the knowledge that all six state premiers (3 ALP; 2 Liberal; 1 Country Party) were opposed.

The government, however, reintroduced the bills in the House instead of bringing on the bills on the Senate notice paper for debate.

The second Seas and Submerged Lands Bill was eventually amended on the ground that the proposed mining code vested too much power in the minister; the second Seas and Submerged Lands (Royalty on Minerals) Bill was rejected as having no relevance following rejection of the mining code.

The Compensation (Commonwealth Employees) Bill 1973 was postponed, inter alia, to await a report on national rehabilitation and compensation from a committee chaired by Mr Justice Woodhouse. Consideration was resumed in committee of the whole on 11 December 1973; on motion by an Opposition senator, progress was reported and further consideration deferred until the first sitting day of the Senate after 21 February 1974.

The Constitution Alteration (Inter-change of Powers) Bill 1973 was deferred until after its proposals had been considered by all state governments and by the Australian Constitutional Convention.

Three bills were referred to committees: the Constitution Alteration (Simultaneous Elections) Bill 1973 to the Standing Committee on Constitutional and Legal Affairs (a move deemed by the government to be a failure to pass); the Australian Industry Development Corporation Bill 1973 and the National Investment Fund Bill 1973 to a Select Committee on Foreign Ownership and Control.

The following legislation was amended and the amendments were accepted by the House of Representatives:

- Pipeline Authority Bill 1973

- Cities Commission Bill 1973

- Australian National Airlines Bill 1973

- Australian Citizenship Bill 1973

- States Grants (Advanced Education) Bill 1973

- States Grants (Universities) Bill 1973

- Australian Capital Territory (House of Representatives) Bill 1973

- Schools Commission Bill 1973

- States Grants (Schools) Bill 1973.

The House did not, however, accept Senate amendments to the Constitution Alteration (Mode of Altering the Constitution) Bill 1973. A second bill, amended in similar manner, was laid aside at the third reading because it did not pass the Senate by an absolute majority as required by the Constitution.

The following bills were rejected by the Senate:

- Commonwealth Electoral Bill (No. 2) 1973: second reading negatived on 17 May 1973; after an interval of three months, bill again passed by House of Representatives; second reading negatived in Senate on 29 August 1973.

- Conciliation and Arbitration Bill 1973: second reading negatived on 6 June 1973. (A second bill passed by House but not in same terms, certain contentious provisions being eliminated or amended. Thirty amendments made to the second bill, all of which were accepted by the House.)

- Senate (Representation of Territories) Bill 1973: Second reading negatived on 7 June 1973; after interval of three months, bill again passed by the House; second reading negatived by Senate on 14 November 1973.

- Representation Bill 1973: Second reading negatived on 7 June 1973; after interval of three months, bill again passed by House (27 September 1973) but second reading negatived by Senate (14 November 1973).

- Constitution Alteration (Democratic Elections) Bill: second reading negatived (4 December 1973).

- Constitution Alteration (Local Government Bodies) Bill: second reading negatived (4 December 1973).

- Health Insurance Commission Bill 1973: second reading negatived (13 December 1973). In addition, the second reading of the Health Insurance Bill 1973 was rejected by way of amendment (12 December 1973).

- Petroleum and Minerals Authority Bill 1973: received from House of Representatives on 13 December 1973; debate adjourned until first sitting day in February 1974; restored to notice paper following prorogation on 12 March 1974; second reading negatived on 2 April 1974.

By the time that the Opposition declared its intention to block appropriation legislation on 4 April 1974, three bills, the Commonwealth Electoral Bill (No. 2) 1973; Senate (Representation of Territories) Bill 1973; and Representation Bill 1973, provided the basis for a simultaneous dissolution. In the period leading up to the Proclamation dissolving the Parliament on 11 April 1974, the government reintroduced, and the Senate negatived, the two Health Insurance Bills and the Petroleum and Minerals Authority Bill (although the latter was negatived for the first time in the Senate on 2 April 1974, the government appeared to argue that the three months period commenced on 12 December 1973 when the House of Representatives first passed the bill, an argument subsequently rejected by the High Court).

The government's proposals for amending the Constitution were also rejected by the Senate. Such legislation, however, is governed by special procedures contained in section 128 of the Constitution rather than by the provisions of section 57. Under the second paragraph of section 128, legislation proposing a referendum, if passed by either House by an absolute majority, and is, in the same form, passed again by an absolute majority after an interval of three months, may be submitted to the electors even if the other house rejects or fails to pass it, or passes it with any amendment to which the first-mentioned house will not agree. Accordingly, the Senate's concurrence was not necessarily required in order to hold a referendum to amend the Constitution.

It was, however, not only in legislation that the government experienced vigorous second chamber scrutiny. Scrutiny manifested itself with particular force in four matters during 1973.

On 7 March 1973 the Opposition successfully moved disallowance of a determination of the Public Service Arbitrator increasing annual leave of public servants from three to four weeks but in effect confining eligibility to members of the staff associations which made application to the Arbitrator. The determination was disallowed on the basis that public servants should not be compelled to join a union in order to enjoy a benefit which it was considered should be in the nature of a common rule. It was also considered that as the Public Service Act made explicit provision for three weeks annual leave, the appropriate method for introducing an entitlement of four weeks was by way of amending the legislation. The Public Service Act was subsequently amended for this purpose. The Senate later (29 March 1973) disallowed the Matrimonial Causes Rules. Opposition to these rules included argument that, while the Senate was not opposed to divorce reform, the rules were not consistent with the Act and were of a nature that should be implemented by legislation, not by executive regulations.

Terrorist activity in Australia was another issue. The Senate considered that a board of inquiry consisting of three High Court or Supreme Court justices should be established by the government to inquire into terrorist activity in Australia and the actions of the Attorney-General in entering the Canberra and Melbourne offices of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, accompanied by Commonwealth police officers. The Senate's opinion was expressed in a resolution which was agreed to on 12 April 1973.

The government, however, declined to appoint the proposed board of inquiry. The Senate responded by proposing (on the motion of the Democratic Labor Party) that a select committee be appointed on civil rights of migrant Australians, including the circumstances surrounding and relevant to the Attorney-General's actions in relation to ASIO. This motion was negatived on 10 May 1973, when the government cancelled pairs, the government contending that “all pairs are off” if there is anything which amounts to a vote of confidence, and the proposed inquiry, it was argued, involved that question in relation to the Attorney-General. It was further argued that the non-government parties had broken convention by not providing that the proposed committee should have a chair from the government side and also a majority of government votes even if (as was the case) the government were in a minority on the floor of the Senate.

The breaking of pairs which led to the defeat of the select committee motion caused considerable bitterness and the Leader of the Opposition (Senator Withers) announced that, at the next sitting, he would give notice for the rescission of the vote negativing the appointment of the select committee. This was done and, on 17 May 1973, the Senate reversed the vote of 10 May and a Select Committee on Civil Rights of Migrant Australians was appointed, consisting of seven senators, three to be nominated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate and four other senators, one to be nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate, one to be nominated by the Leader of the Democratic Labor Party, one to be nominated by the Leader of the Australian Country Party in the Senate and one Independent senator to be nominated by the independent senators.

There was speculation in the press as to whether the government would nominate members to the committee. In the event, government senators served on the committee. (The committee had not reported when both Houses were dissolved on 11 April 1974 and the committee was not re-appointed in the new Parliament.)

Added to these non-legislative disputes was the matter of the Address-in-Reply. To the usual motion for the adoption of a formal Address-in-Reply, the Leader of the Opposition (Senator Withers) moved an amendment criticising the government's economic, defence and foreign policies. There was precedent in 1914 for an amendment critical of government policies but, as in 1914, the government in 1973 believed there were other forms of the Senate to propose such matters and, as the session proceeded, the Address-in-Reply debate was put aside for consideration of the legislative program. The Address-in-Reply, as amended, was eventually agreed to on 30 August 1973, and presented on 19 September, but no government senator attended Government House for the presentation of the address.

On 10 April 1974 the Prime Minister advised a simultaneous dissolution based on six bills:

- Commonwealth Electoral Bill (No. 2) 1973;

- Senate (Representation of Territories) Bill 1973;

- Representation Bill 1973;

- Health Insurance Commission Bill 1973;

- Health Insurance Bill 1973;

- Petroleum and Minerals Authority Bill 1973.

He claimed that each proposed law was of “importance to the Government”. He also drew attention to other legislation which, he asserted, had “in one way or another been the subject of unreasonable obstruction in the Senate”. The Prime Minister referred also to legislation proposing amendments to the Constitution, and to Opposition action concerning Appropriation bills.

Prime Minister Whitlam also made reference to previous simultaneous dissolutions. That of 1914, he wrote, had been granted partly on the basis that a dissolution of the House alone “might well not resolve the political situation, and that a situation under section 57 of the Constitution being in existence, a dissolution of both Houses should be ordered”.

With reference to the simultaneous dissolution in 1951, the Prime Minister observed that Prime Minister Menzies had drawn attention to “difficulties” relating to other legislation and “that this indicated a continuing conflict between the two Houses”.

He concluded: “It is the Government's view that the present circumstances are analogous to those in which the earlier dissolutions were granted ...”.

The Governor-General's reply was, however, confined to the matter as it related to section 57. He wrote to the Prime Minister: “As it is clear to me that grounds for granting a double dissolution are provided by the Parliamentary history of the six bills ..., it is not necessary for me to reach any judgment on the wider case you have presented that the policies of the government have been obstructed by the Senate. It seems to me that this is a matter for judgment by the electors”.

The Prime Minister's advice included, as an attachment, an opinion of the Attorney-General and the Solicitor-General on application of section 57 to more that one proposed law. Their view was “that section 57 of the Constitution is applicable to more than one law at each of the stages it refers to”. The Attorney-General also furnished detailed advice on the application to each proposed law of section 57.

In responding to the Prime Minister the Governor-General stated that, in agreeing to the advice tendered on simultaneous dissolutions, he had “accepted the learned Opinion of the Attorney-General on the requirements for the exercise of the Governor-General's power under section 57 and the Joint Opinion of the Attorney-General and the Solicitor-General on the question whether section 57 is applicable to more than one proposed law”.