Michael Klapdor

Social security and welfare expenditure in 2018–19 is

estimated to total $176.0 billion, representing 36 per cent of the

Australian Government’s total expenses.[1] This administrative

category of expenditure consists of a broad range of services and payments to

individuals and families. It includes:

-

most income support payments such as pensions and allowances (for

example, the Age Pension and Newstart Allowance)

-

family payments such as Family Tax Benefit and the new Child Care

Subsidy

-

Parental Leave Pay

-

funding for aged care services

-

the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) and

-

payments and services for veterans and their dependants.

Other programs associated with the welfare state such as

health and education (including income support for students) are not included

in the welfare category reported in the budget papers.

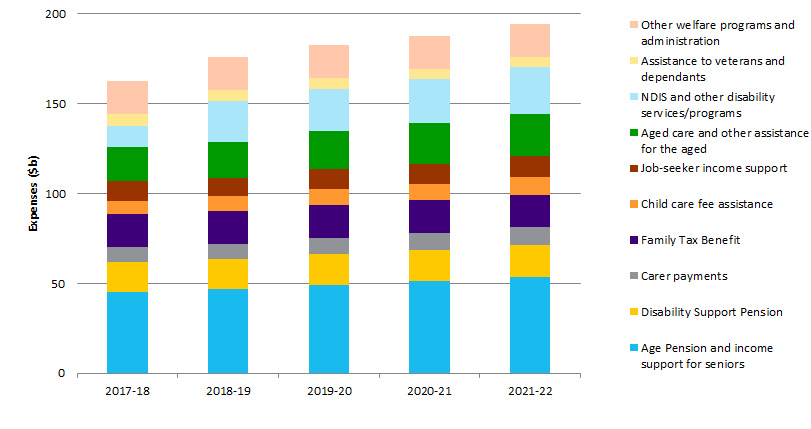

While total expenditure on social security and welfare is

expected to increase from around $162.6 billion in 2017–18 to $194.3 billion in

2021–22, there are different trends within sub-categories of expenditure.

Figure 1 provides a breakdown of the welfare expenditure

category showing key sub-categories including major payments and services.[2]

Figure 1: estimated Australian

Government expenses on social security and welfare, $m

Source: Australian

Government, Budget strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2018–19, pp. 6-23-6-27.

Key drivers of expenditure

increases

The biggest driver of growth in social security and welfare

in coming years is the NDIS. Total funding for the scheme is projected to increase

from $7.8 billion in 2017–18 to an estimated $23.6 billion in 2021–22, with

just over half of this expenditure contributed by the Australian Government.

Overall expenditure on assistance to people with

disabilities is projected to increase by 26.9 per cent in real terms (adjusting

for inflation) from 2017–18 to 2018–19 , with most of this driven by the NDIS. In

contrast to the NDIS, expenditure on the Disability Support Pension (DSP) is

estimated to decrease by 2.3 per cent in real terms from 2017–18 to

2018–19.

The biggest component of social security expenditure, the

Age Pension and other income support for seniors, will increase from $45.1

billion in 2017–18 to $53.8 billion in 2021–22 (an increase of 6.9 per cent in

real terms from 2018–19 to 2021–22). Aged care services expenditure will also

increase from $16.6 billion in 2017–18 to an estimated $22.1 billion in

2021–22. According to the budget papers, this is largely the result of demographic

factors rather than policy decisions.[3]

Expenditure on payments for job-seekers (including Newstart

Allowance and Youth Allowance (Other)) will increase slightly from $11.1

billion in 2017–18 to $11.9 billion in 2021–22.

A number of areas are expected to see a decline in

expenditure:

-

A decrease in the number of veterans and their dependants will result

in a 17.5 per cent decrease in veterans’ community care and support expenditure

in real terms from 2018–19 to 2021–22.

-

Family Tax Benefit expenditure will decrease from $18.5 billion

in 2017–18 to $17.9 billion in 2021–22 despite population growth—primarily as a

result of policy measures to restrict eligibility and freeze the indexation of

payment rates and income test thresholds.

-

Parenting Payment expenses will decrease by 3.5 per cent in real

terms from 2018–19 to 2021–22 as a result of enhanced compliance measures.

Parameter changes

Since the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook was released

in December 2017, there have been some major revisions to estimated expenditure

on a number of social security payments based on changes to the parameters used

in calculating the estimates. Expenditure on DSP has been revised down by $4.5 billion

over the four years to 2021–22 due to a reduction in the number of expected

recipients. The impact of changes made to the pension qualifying age in 2009

has also been revised, producing a decrease in expenditure on the Age Pension of

$2.3 billion over the four years to 2021–22.

No increase in allowance payment

rates

Despite a concerted campaign from community groups, supported

by key business lobby groups, the Government did not announce any budget

measures to raise the level of support for those on Newstart Allowance or Youth

Allowance.[4] In fact, the Government

will proceed with its proposal to close the Energy Supplement—a reduction in

the level of assistance to new recipients of these allowance payments, and to

new recipients of all income support payments.[5] Media reports prior to

the Budget suggested the Government would reverse this 2016–17 budget measure.[6]

An Australian Greens 2016 election policy, costed by the Parliamentary

Budget Office, estimated a $55 per week increase in the single rate of Newstart

Allowance and Youth Allowance would cost around $1.9 billion per annum, or

$7.6 billion from 2016–17 to 2019–20.[7]

[1].

The budget figures in this brief have been taken from the following

document unless otherwise sourced: Australian Government, Budget

strategy and outlook: budget paper no. 1: 2018–19, pp. 3-24, 6-23-6-27.

[2].

The majority of expenditure on these payments and services is provided

through special appropriations rather than the annual Appropriation Bills.

[3].

Ibid., p. 6-23.

[4].

Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS), ‘Raise the rate’, ACOSS

website; T McIlroy, ‘Westacott

dismisses MP’s talk of living on $40 a day’, Australian Financial Review,

4 May 2018, p. 6.

[5].

M Klapdor, ‘Power

play: will the Energy Supplement be saved’, FlagPost, Parliamentary Library

blog, 27 March 2018.

[6].

S Martin, ‘Treasurer

to backflip on pension cut’, West Australian, 2 May 2018, p. 8.

[7].

Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO), ‘Appendix G: Costing documentation

for the Greens’ election commitments’, Post-election

report of election commitments, PBO, Canberra, 5 August 2016, p. 563.

All online articles accessed May 2018.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.