On 1 August 2023, the Senate

Select Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media released its final

report. The committee’s work in the 47th Parliament followed on from a 2019

Select

Committee on Foreign Interference through Social Media, which tabled a First

Interim Report (in December 2021) and a Progress

Report (in April 2022) before dissolving

following the calling of the 2022 federal election.

Since that time, the foreign interference threat facing

Australia has grown in both size and complexity. This is reflected in the committee’s

final report, which opens with the emphatic statement that ‘Foreign

interference is now Australia’s principal national security threat which risks

significantly undermining our values, freedoms and way of life’, before going on

to assert:

Foreign authoritarian states … do not permit open and free debates

on their own social media platforms. They use ours as a vector for their information

operations to shape our decision-making in their national interest – contrary

to ours.

Effectively countering foreign interference through social

media is therefore one of Australia’s most pressing security challenges. (p.

xi) [1]

Australia is not alone in facing a serious threat from

foreign interference activities emanating from or directed by authoritarian

regimes. Many other liberal democracies face similar challenges. The

committee’s report is likely to be closely inspected in Western capitals and

has already attracted

international media attention.

This quick guide provides a brief overview of the committee’s

exploration of foreign interference through social media and current domestic

and international responses to the threat, highlights a number of its recommendations,

and identifies some areas for further consideration. An Annex provides all of

the committee’s recommendations in table form.

The foreign interference ecosystem

The committee report contributes important insights into the

evolving manifestations of foreign interference in which social media is a

vector, particularly with respect to the various tactics and strategies utilised

by authoritarian regimes. Of note, the committee found that in addition to the

use by authoritarian states of tools such as bots, troll farms and content farms

to spread mis- and disinformation, new trends are emerging (pp. 24–25).

Foreign-Interference-as-a-Service

(FaaS)

Among the trends identified by the committee as a ‘national

security threat’ is the emergence of FaaS, which refers to private companies

that ‘offer fee-based interference services’ (p. 26). The report cited the

activities of one entity that not only provided disinformation, but combined this

with other reinforcing activities such as staging a fake protest, which was

then circulated on social media as further disinformation (p. 27).

The emergence of private actors providing FaaS and the use

of such services by state actors makes the threat broader. This has significant

implications for how counter-foreign interference strategy is formulated and implemented,

and for international cooperation on the issue.

The extent of foreign interference

activities targeting Australia

With the exception of TikTok, all of the social media

platforms that appeared before the committee stated that they ‘found and

removed CIB [co-ordinated inauthentic behaviour] that sought to influence

Australia’ (p. 154).

While foreign interference is often conceived of as

interference in elections or political activities, the committee’s inquiry also

found that information

operations have been used against Australian companies. For example, the

committee pointed to a Home Affairs submission that described how Australian

mining company Lynas Rare Earths was targeted by an information operation

seeking to undermine efforts to diversify global rare-earth supply chains (p.

8).

The committee also cited statistics from LinkedIn in relation

to fake accounts, with 400,000 attributed to Australia from more than 80

million worldwide in 2022 and pointed to the platform becoming ‘heavily abused

by threat actors’ in recent years (p. 89). Elsewhere, the report referenced the

alleged contact via LinkedIn between an Australian (who has been charged with

reckless foreign interference) and what were reported to have been suspected

agents of China’s Ministry of State Security (p. 72).

Current domestic and international

approaches to tackling foreign interference

The need to bolster Australia’s current approach to tackling

foreign interference through social media is a key theme of the report, which says

it is urgently required. It also notes the challenges associated with doing so,

contending that ‘in order to identify gaps in countermeasures … it is vital to

accurately map the steps currently being taken’ (p. 71).

The committee mapped current legislative settings and

responsibilities of Australian government entities working to counter foreign

interference (pp. 54–62). It detailed several pieces of legislation applicable

to countering foreign interference including the:

-

Criminal Code Act 1995

-

National Security Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign

Interference) Act 2018

-

Foreign Influence Transparency Scheme Act 2018

-

Online Safety Act 2021

-

Privacy Act 1988[2]

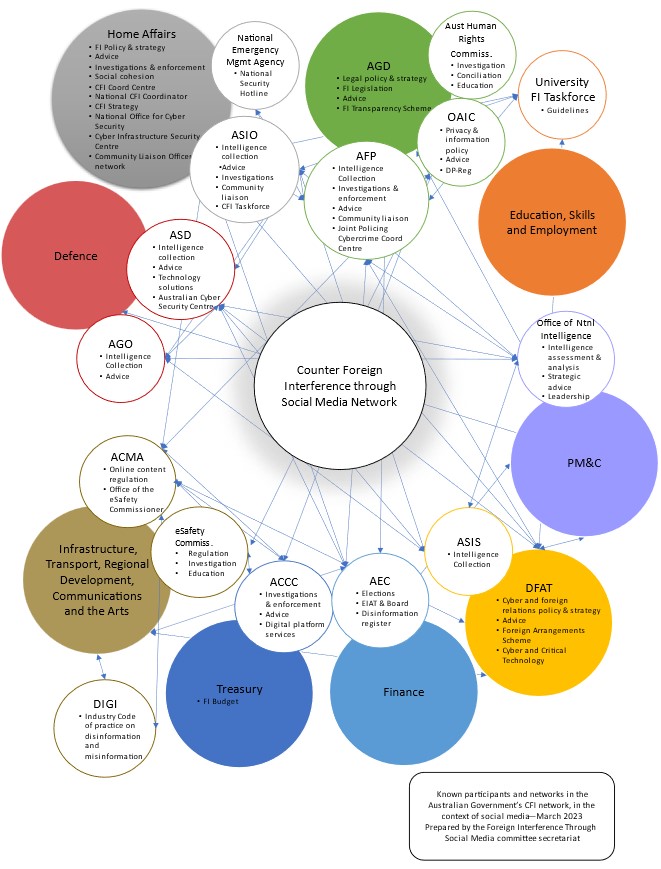

The committee also mapped Australian government entities

and the connections between them as they relate to tackling foreign interference,

as shown in Figure 1 below. The diagram highlights the complex and fragmented

nature of current arrangements.

Figure 1 Counter foreign interference network

Source: Senate Select

Committee on Foreign Interference through

Social Media, Select Committee on Foreign Interference through

Social Media final report, August 2023: 55 (prepared by Monique Nielsen, Committee

Office, Department of the Senate).

The committee also carefully explored and detailed international

approaches to tackling foreign interference, including initiatives put in place

by Europe and the US to use ‘a common methodology for identifying, analysing

and countering’ the activity (p. 158). Ensuring interoperability of systems and

standard methodologies and terminologies will be important to the efforts of

liberal democracies to counter foreign interference.

Notably, in its recommendation that Australia designate an

entity with lead responsibility for whole-of-government efforts to counter

cyber-enabled foreign interference (recommendation 6), the committee also

outlined the importance of Australia’s designated lead entity moving to

‘quickly … adopt the same standards and join’ the efforts of the US and Europe

(p. 158).

Committee recommendations of note

The report contains 17 recommendations, which are outlined

in full in the Annex. This section discusses some of the key recommendations.

Recommendation 1 – mandatory transparency

requirements

This recommendation would impose a set of mandatory ‘transparency

requirements, enforceable with fines’ (p. 149) on social media platforms

operating in Australia. The requirements include mandating that: platforms

‘must have an Australian presence’, ‘disclose which countries they have

employees operating in and who can access Australian data, and keep auditable

logs of any instances of Australian data being transmitted, stored or accessed

offshore’ (pp. 149–150).

The requirements also mandate a series of disclosures

platforms must make, which include disclosing: ‘any government directions they

receive about content on their platform’; ‘cyber-enabled foreign interference

activities … originating from foreign authoritarian governments’ on their

platform; ‘takedowns of coordinated inauthentic behaviour networks’; removal or

adverse action against an elected official’s account; and ‘any changes to the

platform’s data collection practices or security protection policies’. There is

also a requirement that platforms maintain ‘a public library of advertisements

on their platform’ and ‘make their platform open to … researchers to examine

cyber-enabled foreign interference activities’ (pp. 149–150).

While some of the disclosures outlined in the recommendation

are already being implemented by several platforms in order to comply with the

EU’s Code

of Practice on Disinformation and Digital

Services Act (DSA), and Australia’s

existing voluntary code, the committee’s recommendations would make such

disclosures mandatory in Australia. The recommendation does not explain how,

or via what authority, such a ‘system of enforceable minimum transparency

standards’ would operate beyond the recommendation’s outline that if platforms repeatedly

failed to meet the requirements, they could ‘as a last resort, be banned by the

Minister for Home Affairs via a disallowable instrument’ (p. 149).

Recommendations 3, 4 and 5 – extended

platform bans

These recommendations call for an expansion of the TikTok

ban on Government devices enacted by the Attorney-General in April 2023.

Recommendation 3 sets out an expansion of the

ban on specific applications (such as TikTok) on government devices to

include ‘all government contractors’ devices who have access to Australian

government data’ and the ‘work-issued devices of entities designated as Systems

of National Significance’(SoNS).

SoNS are a subset of designated critical infrastructure

assets that are the most important to Australia because of their

interdependencies and the potential for serious and cascading consequences to

other critical infrastructure assets if disrupted, and the consequences that

would arise for the country’s ‘social

or economic stability, defence or national security’. If a critical

infrastructure asset is declared a SoNS, it may be subject to Enhanced Cyber

Security Obligations.

A ban covering the devices of entities operating an asset

declared a SoNS is a significant expansion as it would extend the ban into the

private sector. Exactly who it would cover is not known because the assets ‘cannot

be publicly named’.

The report details the potential mechanisms for these

changes on page 156, using information from both Home Affairs and the Attorney-General’s

Department (AGD).

For bans on SoNS, the report cites a budget

estimates hearing for Home Affairs on May 22 2023 (p. 67) where executives

suggested such a ban could be accomplished under the Security of

Critical Infrastructure Act (SOCI Act) using the risk assessment

obligations for SoNS, or the ministerial directions enabled by section 32 of

the SOCI Act. In relation to the report’s recommendation to place bans on

contractor phones, the Protective Security Policy Framework’s ICT systems

policy appears to already specify that the same security requirements apply to

outsourced providers. However, it is not clear that there is any centralised

oversight of compliance. The report cites the AGD and notes:

…while the PSPF also applied to government contractors, AGD

did not have oversight over whether departments had turned their minds to

ensuring contractors either knew about or were adhering to the TikTok ban. (p.

155)

Recommendation 4 recommends that the government ‘consider

extending the Protective Security Policy Framework directive banning

TikTok on federal government devices to WeChat’ (p. 156).

In addition to multiple submissions and witnesses raising

concerns about WeChat, the report highlights that ‘WeChat repeatedly declined

multiple invitations to participate in a public hearing’ (p. 90) and when the

committee’s chair ‘submitted 53 detailed questions to WeChat … WeChat failed to

meet the transparency test by not providing direct answers to the questions

that were asked of them’ (p. 91).

Recommendation 5 emphasises the need to continually ‘audit

the security risks posed by the use of all other social media platforms on

government-issued devices within the Australian Public Service, and issue

general guidance regarding device security, and if necessary, further

directions under the Protective Security Policy Framework’ (p. 156).

Together, these recommendations could be viewed as suggesting

that the committee is putting forward a platform-specific approach as the way

to address the foreign interference risks social media apps can pose.

The pursuit of a platform-specific approach instead of platform

agnostic standards-based approach is contentious as policy. Government senators

(p. 170) and the Australian Greens (p. 173) commented that platform-specific

policy is ‘a game of digital whack-a-mole’, which the report attributes

elsewhere to multiple witnesses (p. 71).

The government may be considering alternative approaches. During

budget estimates on 22 May 2023 (p. 69), Home Affairs described ‘a review

of social media issues generally, presented to the government on 16 March’,

which covered risks including ‘high-risk data vulnerabilities’. Home Affairs also

outlined varied international approaches ‘from India, which has a complete ban

on some applications economywide, to the French government, which looks at

banning [all] recreational applications [on

government devices]’ (p. 69).

Recommendation 6 and 7 –

responsible entities

Recommendation 6 provides for the establishment of ‘a

national security technology office within the Department of Home Affairs to

map existing exposure to high-risk vendors such as TikTok, WeChat and any

similar apps that might emerge in the future’. The committee envisaged that the

office could ‘recommend mitigations to address the risks of installing these

applications, and where necessary, ban them from being installed on government

devices’ (p. 157).

The report does not appear to advocate for the development

of a methodology for assessing apps in a manner that would support a platform

agnostic approach, further reinforcing the platform-focused nature it appears

to have adopted.

It is also unclear how the mapping role would interact with agencies

that currently advise government on IT vendors, including the Australian Cyber

Security Centre (ACSC), the Digital Transformation Agency (DTA), and AGD under

the PSPF.

Recommendation 7 identifies the need to ‘designate an

entity with lead responsibility for whole-of-government efforts to counter

cyber-enabled foreign interference, with appropriate interdepartmental support

and collaboration, resources, authorities and a strong public outreach mandate’

(p. 158).

The committee’s mapping of organisations involved in

countering foreign interference highlighted the varied and overlapping

responsibilities among them. Implementation of recommendations 6 and 7 would

require consideration of how the proposed entity and its roles would interact

with already established entities with an existing role.

For example, it is unclear how a lead entity for

cyber-enabled foreign interference tasked to cover collaboration within

government and outreach to the public would interact with the existing roles of

the eSafety Commissioner or the newly established Cybersecurity Coordinator

under Home Affairs. There may be overlap with functions and roles within the ACSC,

the Critical Technologies Hub within the Department of Industry, Science and

Resources (DISR), the DTA, the eSafety Commissioner, and the newly established

Cybersecurity Coordinator within Home Affairs.

Further consideration is potentially required as to whether

this entity would have any role in assessing reporting from platforms as

outlined in recommendation 1, or whether this would be the sole purview of the

office established within Home Affairs, as outlined in recommendation 6. The

report’s discussion of recommendation 7 highlights the current operational

restrictions on Home Affairs, but does not explicitly recommend addressing

them.

In particular, the discussion notes that ‘despite having

responsibility to run the Counter Foreign Interference Coordination Centre, [Home

Affairs] was not a member of the Counter Foreign Interference Taskforce’ (p.

157), and that when a new community outreach program was established in ’February

this year … Home Affairs … was not given any new resources to undertake this

work’ (pp. 157–158). Elsewhere, the report notes that no new funding was provisioned

in the Budget for the ‘establishment of the Coordinator for Cyber Security

within Home Affairs’ (p. 63).

Recommendation 9 – sanctions

The recommendation sets out that cyber-enabled foreign

interference actors should be included as targets for Magnitsky-style cyber

sanctions under the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011.

Under

a regime introduced on 21 December 2021, Australia can already impose

sanctions in relation to significant cyber incidents, but these do not cover

cyber-enabled foreign interference activities of the kind the committee’s final

report details.

The use of sanctions to target foreign interference is already

in use by the EU, which, at the end of July 2023, imposed

sanctions against Russian individuals and entities who it alleged were responsible

for a digital information manipulation campaign. In the press release the

EU noted that this measure and others it adopted were part of its policy to

address foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI).

While sanctions can be a useful tool and are increasingly being

adopted, their impact can be limited. In addition to cryptocurrencies, some

actors still use cash, which

allows them to potentially evade sanctions.

Moreover, while sanctions can be imposed, enforcing

compliance can be difficult – particularly in relation to cryptocurrency

payments. The financial intelligence units of many countries are yet to be

empowered with legislation that improves the currently limited visibility many

have in relation to the financial activities of criminal actors using

cryptocurrency.

Although the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) extended

anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (AML/CTF) measures in 2019 to also cover cryptocurrencies

and associated services (referred to by FATF as virtual assets (VA) and virtual

asset service providers (VASP) respectively), Australia, like many other

countries, has not fully implemented FATF’s recommendations. As a result, Australia

currently only has visibility of digital currency exchanges (DCE), as it does

not yet regulate VASPs (such as crypto mixing

services).

Areas for further consideration

Other apps and platforms

The committee’s final report is especially concerned with

specific risks on ‘platforms which originate from authoritarian states’ (p. 87),

and its recommendations focus mostly on TikTok and WeChat, which are widely

used in Australia. However, there exist a number of other apps in use in

Australia that may be vectors for cyber-enabled foreign interference, including

but not limited to several others originating from China.

Weibo, a

second pillar of Chinese social media along with WeChat, has users among

both the

Chinese diaspora in Australia and the Australian government, including

former prime minister Kevin

Rudd, the

Australian embassy in China and Tourism

Australia. Crikey

noted that video editing app CapCut[3]

and shopping apps SHEIN and Temu were among the 20 most popular apps in

Australia.

Determining what constitutes high risk in relation to

cyber-enabled foreign interference in a platform-agnostic manner is potentially

worthy of further consideration. Platforms operating outside of authoritarian

states can also be manipulated, compromised or otherwise involved in foreign

interference activities, and varying ownership models could also influence the

degree to which platforms cooperate with authorities.

Twitter (recently renamed ‘X’), which was acquired by Elon

Musk just prior to the start of the committee inquiry and was subsequently

taken private, is one such case. According to media reports, Twitter was

purchased with support from a range of investors. Following news that Musk’s

investors included ‘Prince Alwaleed bin Talal of Saudi Arabia and Qatar

Holding, an investment firm owned by the Arab country’s sovereign wealth fund’,

questions were raised about this potentially posing a threat to US national

security. US President Joe Biden was quoted as saying

‘I think that Elon Musk’s cooperation and/or technical relationships with other

countries is worthy of being looked at’. It was also reported

that ‘other investors in Musk’s Twitter purchase have ties to China and the

United Arab Emirates’.

The purchase of Twitter and its move to a different

ownership model appears to have impacted transparency and accountability. Reuters

reported in January that ‘a Twitter program that was critical for outside

researchers studying disinformation campaigns’, which had included a

partnership with the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), had

stalled as ‘nearly all … employees who worked on the consortium have left the

company’. In

June 2023, the eSafety Commissioner ‘issued a legal notice to Twitter’ due

to ‘an increasing number of reports of serious online abuse since Elon Musk’s

takeover of the company’. The committee’s final report does reference some of

these issues in relation to Twitter/X.

The report cites the Human Rights Watch submission, which asserted

that while Twitter had been accused of negligence prior to the acquisition, the

company had ‘quickly reacted to requests to protect the accounts of Chinese

human rights defenders’ and that ‘the gutting of the infrastructure and staff

that deal with these issues threatens to change that equation between the

platform and China’ (pp. 95–96).

The apparent waning of Twitter’s initiatives to combat disinformation

was also highlighted in the report. It quotes the European

Commission noting in its announcement of the first reports under the EU’s Code of Practice on Disinformation that ‘Twitter,

however, provides little specific information and no targeted data in relation

to its commitments’ (p. 34). (The European Commissioner for Internal Market announced in May 2023

that Twitter had pulled out of the disinformation code, but he noted that the Digital

Services Act would impose mandatory obligations from 25 August 2023.)

Implementation

The report’s foreword notes the need for ‘urgent action to

ensure Australia stays ahead of the threat’. In this respect, Australian

National Audit Office ‘audit insights’ on the Rapid

implementation of Australian Government initiatives, and Implementation

of recommendations, are useful resources to consider in relation to

some key risks that may affect the successful delivery of the outcomes

envisaged by the committee.

One key area in which attention may need to be focused is the

creation of an implementation framework. The creation of an implementation

strategy and framework against which effective governance arrangements can be

established, monitored and tracked will also be important to ensuring the

successful implementation of the recommendations.

Annex – full list of recommendations

Chapter 8 of the committee’s report outlines all 17 recommendations

in the form of a detailed discussion of the background, followed by specific recommendations

for action by the Australian Government. The below table contains the text of each

recommendation, together with the relevant paragraph and page numbers, and the page

numbers on which the associated discussion can be found.

|

Recommendation

|

Text

|

|

1

Paragraphs 8.43–44 (p. 149); discussion

(pp. 145–149)

|

Require all large social media

platforms operating in Australia to meet a minimum set of transparency

requirements, enforceable with fines. Any platform which repeatedly fails to

meet the transparency requirements could, as a last resort, be banned by the

Minister for Home Affairs via a disallowable instrument, which must be

reviewed by the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security.

Requirements should include, at

minimum, that all large social media platforms:

-

must have an Australian presence

-

must proactively label state affiliated media

-

must be transparent about any content they censor or account

takedowns on their platform

-

must disclose any government directions they receive about

content on their platform, subject to national security considerations

-

must disclose cyber-enabled foreign interference activity,

including transnational repression and surveillance originating from foreign

authoritarian governments

-

must disclose any takedowns of coordinated inauthentic

behaviour (CIB) networks, and report how and when the platform identified

those CIB networks

-

must disclose any instances where a platform removes or takes

adverse action against an elected official’s account

-

must disclose any changes to their platform’s data collection

practices or security protection policies as soon as reasonably practicable

-

must make their platform open to independent cyber analysts and

researchers to examine cyber-enabled foreign interference activities

-

must disclose which countries they have employees operating in

who could access Australian data and keep auditable logs of any instance of

Australian data being transmitted, stored or accessed offshore

-

must maintain a public library of advertisements on their

platform.

|

|

2

Paragraph 8.61 (p. 154); discussion

(pp. 150–154)

|

Should the United States

Government force ByteDance to divest its stake in TikTok, the Australian

Government review this arrangement and consider the appropriateness of

ensuring TikTok Australia is also separated from its ByteDance parent

company.

|

|

3

Paragraphs 8.69–70 (p. 156); discussion

(pp. 154–156)

|

Extend, via policy or appropriate

legislation, directives issued under the Protective Security Policy

Framework regarding the banning of specific applications (e.g. TikTok) on

all government contractors’ devices who have access to Australian government

data.

The Minister for Home Affairs

should review the application of the Security of Critical Infrastructure

Act 2018, to allow applications banned under the Protective Security

Policy Framework to be banned on work-issued devices of entities designated

of Systems of National Significance.

|

|

4

Paragraph 8.71 (p. 156); discussion

(pp. 154–156)

|

Consider extending the Protective

Security Policy Framework directive banning TikTok on federal government

devices to WeChat, given it poses similar data security and foreign

interference risks.

|

|

5

Paragraph 8.72 (p. 156); discussion

(pp. 154–156)

|

Continue to audit the security

risks posed by the use of all other social media platforms on

government-issued devices within the Australian Public Service, and issue

general guidance regarding device security, and if necessary, further

directions under the Protective Security Policy Framework.

|

|

6

Paragraph 8.74 (p. 157); discussion

(pp. 154–156)

|

Establish a national security

technology office within the Department of Home Affairs to map existing

exposure to high-risk vendors such as TikTok, WeChat and any similar apps

that might emerge in the future. It should recommend mitigations to address

the risks of installing these applications, and where necessary, ban them

from being installed on government devices.

|

|

7

Paragraph 8.80 (p. 158); discussion

(pp. 157–158)

|

Designate an entity with lead

responsibility for whole-of-government efforts to counter cyber-enabled

foreign interference, with appropriate interdepartmental support and

collaboration, resources, authorities and a strong public outreach mandate.

|

|

8

Paragraph 8.82 (p. 158); discussion

(p. 158)

|

Address countering cyber-enabled

foreign interference as part of the 2023–2030 Australian Cyber Security

Strategy.

|

|

9

Paragraph 8.85 (p. 159); discussion

(p. 159)

|

Clarify that Magnitsky-style

cyber sanctions in the Autonomous Sanctions Act 2011 can be used to

target cyber-enabled foreign interference actors, via legislative amendment

if necessary, and ensure it has appropriate, trusted frameworks for public

attribution.

|

|

10

Paragraph 8.90 (p. 160); discussion

(pp. 159–160)

|

Refer the National Security

Legislation Amendment (Espionage and Foreign Interference) Act 2018 to

the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security for review,

with particular reference to the Act’s effectiveness in addressing

cyber-enabled foreign interference.

|

|

11

Paragraph 8.94 (p. 160); discussion

(pp. 160–161)

|

Investigate options to identify,

prevent and disrupt artificial intelligence (AI)-generated disinformation and

foreign interference campaigns, in addition to the Government’s Safe and

Responsible AI in Australia consultation process.

|

|

12

Paragraph 8.97 (p. 161); discussion

(p. 161)

|

Establish a program of vetting

appropriate personnel in trusted social media platforms with relevant

clearances to ensure there is a point of contact who can receive threat

intelligence briefings.

|

|

13

Paragraph 8.107 (p. 163); discussion

(pp. 162–163)

|

Build capacity to counter social

media interference campaigns by supporting independent research.

|

|

14

Paragraph 8.120 (p. 165); discussion

(pp. 163–165)

|

Ensure that law enforcement

agencies, and other relevant bodies such as the eSafety Commissioner, work

with social media platforms to increase public awareness of transnational

repression.

|

|

15

Paragraph 8.124 (p. 166); discussion

(p. 166)

|

Empower citizens and

organisations to make informed, risk-based decisions about their own social

media use by publishing plain-language education and guidance material and

regular reports and risk advisories on commonly used social media platforms,

ensuring this material is accessible for non-English speaking citizens.

Specific focus should be on protecting communities and local groups which are

common targets of foreign interference and provide pre-emptive information

and resources.

|

|

16

Paragraph 8.130 (p. 167); discussion

(pp. 166–167)

|

Support independent and

professional foreign-language journalism by supporting journalism training

and similar programs, thereby expanding the sources of uncensored news for

diaspora communities to learn about issues such as human rights abuses inside

their country of origin.

|

|

17

Paragraph 8.137 (p. 168); discussion

(p. 168)

|

Promote the digital literacy and

the infrastructure of developing countries in the Indo-Pacific region that

are the targets of malicious information operations by foreign authoritarian

states.

|